أمريكا الروسية

| روسكايا أمريكا أمريكا الروسية Русская Америка | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| مستعمرة للامبراطورية الروسية | |||||||||

| 1799–1867 | |||||||||

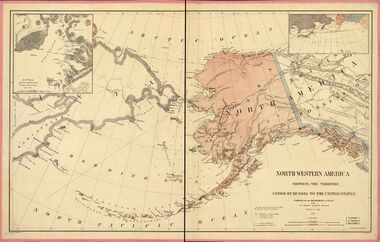

أمريكا الروسية في 1860 | |||||||||

| Anthem | |||||||||

| "Боже, Царя храни!" Bozhe Tsarya khrani! (1833–1867) ("God Save the Tsar!") | |||||||||

| العاصمة | كودياك (1799–1804) نوڤو-أرخانگلسك | ||||||||

| صفة المواطن | Alaskan Creole | ||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||

| • Coordinates | 57°03′N 135°19′W / 57.050°N 135.317°W | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

| الحكومة | |||||||||

| الحاكم | |||||||||

• 1799–1818 (الأول) | Alexander Andreyevich Baranov | ||||||||

• 1863–1867 (الأخير) | Dmitry Petrovich Maksutov | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• Established | 8 يوليو 1799 | ||||||||

| 18 October 1867 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| اليوم جزء من | الولايات المتحدة | ||||||||

| a. ^ The الشركة الأمريكية الروسية أصدر الامبراطور ميثاقاً لها في 1799، لحكم الأملاك الروسية في أمريكا الشمالية نيابة عن الامبراطورية الروسية. | |||||||||

}}

|

| تاريخ ألاسكا |

|---|

| قبل التاريخ |

| أمريكا الروسية (1733–1867) |

| ادارة الاسكا (1867–1884) |

| مقاطعة ألاسكا (1884–1912) |

| أراضي ألاسكا (1912–1959) |

| ولاية ألاسكا (1959–الآن) |

| موضوعات أخرى |

أمريكا الروسية (روسية: Русская Америка، روسكايا أمريكا؛ إنگليزية: Russian America) كان اسم الممتلكات الاستعمارية الروسية في الأمريكتين من 1733 إلى 1867 التي أصبح معظمها اليوم الولاية الأمريكية ألاسكا وأيضاً ثلاث مستوطنات صغيرة إلى الجنوب في كاليفورنيا، منها فورت روس، وثلاث حصون في هاوائي، منهم الحصن الروسي إليزابث. تركزت المستوطنات في ألاسكا، بما في ذلك العاصمة نوڤو-أرخانگلسك (أرخانگلسك الجديدة)، التي هي اليوم سيتكا.

بعد أول هبوط في ألاسكا في منتصف القرن 18، أعلنت روسياً رسمياً إقامة حكمها في المنطقة عبر أوكاسه 1799 (إعلان أو فرمان من القيصر)، الذي أعطى احتكاراً للشركة الروسية الأمريكية كما منح الكنيسة الأرثوذكسية الروسية بعض الحقوق في الممتلكات الجديدة. ازدهرت المستعمرة في البداية من تجارة الفراء، ولكن بحلول منتصف القرن التاسع عشر، أدى الصيد الجائر والتحديات اللوجستية إلى تدهورها التدريجي. مع التخلي عن معظم المستوطنات بحلول ستينيات القرن التاسع عشر، باعت آخر ممتلكاتها المتبقية إلى الولايات المتحدة في عام 1867 مقابل 7.2 مليون دولار (قيمتها اليوم 120 million دولار أمريكي).

Russian expansion eastward began in 1552, and in 1639 Russian explorers reached the Pacific Ocean. In 1725, Emperor Peter the Great ordered navigator Vitus Bering to explore the North Pacific for potential colonization. The Russians were primarily interested in the abundance of fur-bearing mammals on Alaska's coast, as stocks had been depleted by overhunting in Siberia. Bering's first voyage was foiled by thick fog and ice, but in 1741 a second voyage by Bering and Aleksei Chirikov made sight of the North American mainland. Bering claimed the Alaskan country for the Russian Empire.[1] Russia later confirmed its rule over the territory with the Ukase of 1799 which established the southern border of Russian America along the 55th parallel north.[2] The decree also provided monopolistic privileges to the state-sponsored Russian-American Company and established the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska.

Russian promyshlenniki (trappers and hunters) quickly developed the maritime fur trade, which instigated several conflicts between the Aleuts and Russians in the 1760s. The fur trade proved to be a lucrative enterprise, capturing the attention of other European nations. In response to potential competitors, the Russians extended their claims eastward from the Commander Islands to the shores of Alaska. In 1784, with encouragement from Empress Catherine the Great, explorer Grigory Shelekhov founded Russia's first permanent settlement in Alaska at Three Saints Bay. Ten years later, the first group of Orthodox Christian missionaries began to arrive, evangelizing thousands of Native Americans, many of whose descendants continue to maintain the religion.[3] By the late 1780s, trade relations had opened with the Tlingits, and in 1799 the Russian-American Company (RAC) was formed in order to monopolize the fur trade, also serving as an imperialist vehicle for the Russification of Alaska Natives.

Angered by encroachment on their land and other grievances, the indigenous peoples' relations with the Russians deteriorated. In 1802, Tlingit warriors destroyed several Russian settlements, most notably Redoubt Saint Michael (Old Sitka), leaving New Russia as the only remaining outpost on mainland Alaska. This failed to expel the Russians, who re-established their presence two years later following the Battle of Sitka. (Peace negotiations between the Russians and Native Americans would later establish a modus vivendi, a situation that, with few interruptions, lasted for the duration of Russian presence in Alaska.) In 1808, Redoubt Saint Michael was rebuilt as New Archangel and became the capital of Russian America after the previous colonial headquarters were moved from Kodiak. A year later, the RAC began expanding its operations to more abundant sea otter grounds in Northern California, where Fort Ross was built in 1812.

By the middle of the 19th century, profits from Russia's North American colonies were in steep decline. Competition with the British Hudson's Bay Company had brought the sea otter to near extinction, while the population of bears, wolves, and foxes on land was also nearing depletion. Faced with the reality of periodic Native American revolts, the political ramifications of the Crimean War, and unable to fully colonize the Americas to their satisfaction, the Russians concluded that their North American colonies were too expensive to retain. Eager to release themselves of the burden, the Russians sold Fort Ross in 1841, and in 1867, after less than a month of negotiations, the United States accepted Emperor Alexander II's offer to sell Alaska. The Alaska Purchase for $7.2 million (equivalent to $120 million in 2022) ended Imperial Russia's colonial presence in the Americas.

الاستكشاف

The earliest written accounts indicate that the Eurasian Russians were the first Europeans to reach Alaska. There is an unofficial assumption that Eurasian Slavic navigators reached the coast of Alaska long before the 18th century.

في 1648 أبحر سميون دژنيڤ من مصب نهر كوليما عبر المحيط القطبي الشمالي وحول الطرف الشرقي لآسيا إلى نهر أنادير. وتقول أحد الأساطير أن بعض قواربه انجرفت عن مسارها ووصلت ألاسكا. إلا أنه لم يبق دليلاً على الاستيطان. لم يحال اكتشاف دجنيف أبداً إلى الحكومة المركزية، مما ترك المسألة مفتوحة إذا ما تم اتصال بين سيبيريا وأمريكا الشمالية.[4]

وفي 1725، أمر الامبراطور پطرس الأكبر بتجريدة أخرى. كجزء من تجريدة كمتشاتكا الثانية 1733–1743، أبحرت السفينتان Sv. Petr بقيادة الدنماركي ڤيتوس برنگ و Sv. Pavel بقيادة الروسي ألكسي تشيريكوڤ من ميناء [[شبه جزيرة كامشاتكا |كامشاتكا]] پتروپاڤلوڤسك في يونيو 1741. وسرعان ما افترقا، ولكن واصلت كل منهما الإبحار شرقاً.[5]

وفي 15 يوليو، لمح تشيريكوڤ يابسة، لعلها كانت الجانب الغربي من جزيرة أمير ويلز في جنوب شرق ألاسكا.[6] وأرسل مجموعة من الرجال للساحل في قارب طويل، فكانوا أول أوروبيين يهبطوا الساحل الشمالي الغربي لأمريكا الشمالية.

وتقريباً في 16 يوليو، لمح برنگ وطاقم سفينة Sv. Petr جبل القديس إلياس في بر ألاسكا الرئيسي؛ فاستداروا غرباً باتجاه روسيا بعد ذلك مباشرة. بينما أقفل تشيريكوڤ وطاقم Sv. پاڤل عائدين إلى روسيا في أكتوبر بخبر الأرض التي عثروا عليها.

وفي نوفمبر تحطمت سفينة برنگ على جزيرة برنگ. وهناك سقط برنگ مريضاً ومات، وحطمت الرياح القوية السفينة Sv. پيتر إرباً. بعد أن أمضى الطاقم المنعزل الشتاء في الجزيرة، بنى الناجون قارباً من الحطام وأبحروا إلى روسيا في أغسطس 1742. وصل طاقم برنگ ساحل كامتشاتكا في 1742، حاملين أخبار التجريدة. الجودة العالية لفراء قضاعة البحر الذي جلبوه معهم كان دافعاً رئيسياً للاستيطان الروسي في ألاسكا.

الاستيطان الروسي

عقد 1740 حتى 1800

بعد ذلك، بدأت اتحادات صغيرة لتجار الفراء في الابحار من سواحل سيبريا باتجاه جزر ألوشن. ولما أصبحت الرحلات من سيبريا إلى أمريكا تجريدات أطول (لتستمر من سنتين إلى أربع سنوات أو أطول)، أسست الأطقم ثغور قنص وتجارة. وبحلول أواخر عقد 1790، أصبح أولئك مستوطنات دائمة. وقد كان نصف تجار الفراء تقريباً من الروس من مختلف الأجزاء الاوروبية من الامبراطورية الروسية أو من سيبريا. أما الآخرون فقد كانوا من السكان الأصليين لسيبريا أو سيبيريين ذوي الأصول المخلطة من السكان الأصليين والاوروبيين والآسيويين.

وفي 1790، استأجر شلخوڤ، بعد عودته إلى روسيا، ألكسندر برانوڤ ليدير شركته لفراء ألاسكا. نقل برانوڤ المستعمرة إلى الطرف الشمال شرقي لجزيرة كودياك، حيث يتوافر الخشب. وقد أصبح ذلك الموقع لاحقاً مدينة كودياك. وقد تزوج أعضاء المستعمرة الروس من نساء كونياگ وبدأوا عائلات مازالت أسماؤها حتى اليوم، مثل پاناماروف، پتريكوف، وكڤاسنكوف. وفي 1795، أسس برانوڤ، بسبب انزعاجه من رؤية الاوروبيين غير الروس يتاجرون مع المواطنين في جنوب شرق ألاسكا، ميخائيلوڤسك 10 كم شمال ستكا الحالية. وقد اشترى الأرض من التلنگتس، ولكن في 1802، بينما كان برانوڤ مسافراً، قام التلنگتس من مستوطنة مجاورة بالهجوم وتدمير ميخائيلوڤسك. وقد عاد برانوڤ بسفينة حربية وأباد قرية التلنگتس. ثم أنشأ مستوطنة نيو أركانجل. وقد أصبحت عاصمة أمريكا الروسية وهي اليوم مدينة ستكا، التي تغطي ما كان سابقاً منطقة ميخائيلوڤسك.

وبينما كان برانوڤ يؤمـِّن الوجود الفعلي للروسي في ألاسكا، واصلت عائلة شلخوڤ العمل في روسيا للفوز باحتكار لتجارة فراء ألاسكا. وفي 1799، حصل نسيب شلخوڤ، نيقولاي پتروڤيتش رزانوڤ، على احتكار تجارة الفراء الأمريكي من القيصر پاڤل الأول. ثم أسس رزانوڤ الشركة الروسية الأمريكية. وكجزء من الصفقة، توقع القيصر أن تؤسس الشركة مستوطنات جديدة في ألاسكا وأن تقوم ببرنامج استعمار موسع.

1800 إلى 1867

وفي 1804، قوّى ألكسندر برانوڤ، الذي أصبح مدير الشركة الروسية الأمريكية، قبضة الشركة على أنشطة تجارة الفراء في الأمريكتين على إثر انتصاره على قبيلة التلنگتس في معركة ستكا. وبالرغم من تلك الجهود، فإن الروس لم يستعمروا ألاسكا بالكامل قط. فقد كان في الأغلب منحصرين في الساحل ولم يهتموا بالداخل.

من 1812 إلى 1841 فورت روس، كاليفورنيا كانت نشطة. ومن 1814 إلى 1817 كانت فورت إليزابث الروسية تعمل في هاوائي. وبحلول عقد 1830، بدأ الاحتكار الروسي لتجارة الفراء يضعف. وأنشأت شركة خليح هدسون ثغور على الطرف الجنوبي لأمريكا الروسية في 1839 بعقود إيجار ناتجة من محاولة سابقة في 1833 لوقف تأسيس مثل تلك الثغور. وبدأت شركة خليج هدسون في تسريب تجارة الفراء.

الأنشطة الإرسالية

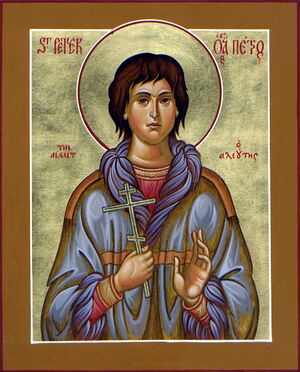

At Three Saints Bay, Shelekov built a school to teach the natives to read and write Russian, and introduced the first resident missionaries and clergymen who spread the Russian Orthodox faith. This faith (with its liturgies and texts, translated into Aleut at a very early stage) had been informally introduced, in the 1740s–1780s. Some fur traders founded local families or symbolically adopted Aleut trade partners as godchildren to gain their loyalty through this special personal bond. The missionaries soon opposed the exploitation of the indigenous populations, and their reports provide evidence of the violence exercised to establish colonial rule in this period.

The RAC's monopoly was continued by Emperor Alexander I in 1821, on the condition that the company would financially support missionary efforts.[7] The company board ordered chief manager Arvid Adolf Etholén to build a residency in New Archangel for bishop Veniaminov[7] When a Lutheran church was planned for the Finnish population of New Archangel, Veniamiov prohibited any Lutheran priests from proselytizing to neighboring Tlingits.[7] Veniamiov faced difficulties in exercising influence over the Tlingit people outside New Archangel, due to their political independence from the RAC leaving them less receptive to Russian cultural influences than Aleuts.[7][8] A smallpox epidemic spread throughout Alaska in 1835-1837 and the medical aid given by Veniamiov created converts to Orthodoxy.[8]

Inspired by the same pastoral theology as Bartolomé de las Casas or St. Francis Xavier, the origins of which were in early Christianity's need to adapt to the cultures of Classical antiquity, missionaries in Russian America applied a strategy that placed value on local cultures and encouraged indigenous leadership in parish life and missionary activity. When compared to later Protestant missionaries, the Orthodox policies "in retrospect proved to be relatively sensitive to indigenous Alaskan cultures."[7] This cultural policy was originally intended to gain the loyalty of the indigenous populations by establishing the authority of Church and State as protectors of over 10,000 inhabitants of Russian America. (The number of ethnic Russian settlers had always been less than the record 812, almost all concentrated in Sitka and Kodiak).

Difficulties arose in training Russian priests to attain fluency in any of the various Indigenous Alaskan languages. To redress this, Veniaminov opened a seminary for mixed race and native candidates for the Church in 1845.[7] Promising students were sent to additional schools in either Saint Petersburg or Irkutsk, the later city becoming the original seminary's new location in 1858.[7] The Holy Synod instructed for the opening of four missionary schools in 1841, to be located in Amlia, Chiniak, Kenai, and Nushagak.[7] Veniamiov established the curriculum, which included Russian history, literacy, mathematics, and religious studies.[7]

A side effect of the missionary strategy was the development of a new and autonomous form of indigenous identity. Many native traditions survived within local "Russian" Orthodox tradition and in the religious life of the villages. Part of this modern indigenous identity is an alphabet and the basis for written literature in nearly all of the ethnic-linguistic groups in the Southern half of Alaska. Father Ivan Veniaminov (later St. Innocent of Alaska), famous throughout Russian America, developed an Aleut dictionary for hundreds of language and dialect words based on the Russian alphabet.

The most visible trace of the Russian colonial period in contemporary Alaska is the nearly 90 Russian Orthodox parishes with a membership of over 20,000 men, women, and children, almost exclusively indigenous people. These include several Athabascan groups of the interior, very large Yup'ik communities, and quite nearly all of the Aleut and Alutiiq populations. Among the few Tlingit Orthodox parishes, the large group in Juneau adopted Orthodox Christianity only after the Russian colonial period, in an area where there had been no Russian settlers nor missionaries. The widespread and continuing local Russian Orthodox practices are likely the result of the syncretism of local beliefs with Christianity.

Observers noted that while their religious ties were tenuous, before the sale of Alaska there were 400 native converts to Orthodoxy in New Archangel.[8] Tlingit practitioners declined in number after the lapse of Russian rule, until there were only 117 practitioners in 1882 residing in the place, by then renamed as Sitka.[8]

بيع ألاسكا للولايات المتحدة

By the 1860s, the Russian government was ready to abandon its Russian America colony. Over-hunting had severely reduced the fur-bearing animal population, and competition from the British and Americans exacerbated the situation. This, combined with the difficulties of supplying and protecting such a distant colony, reduced interest in the territory. In addition, Russia was in a difficult financial position and feared losing Russian Alaska without compensation in some future conflict, especially to the British. The Russians believed that in a dispute with Britain, their hard-to-defend region might become a prime target for British aggression from British Columbia, and would be easily captured. So following the Union victory in the American Civil War, Tsar Alexander II instructed the Russian minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl, to enter into negotiations with the United States Secretary of State William H. Seward in the beginning of March 1867. At the instigation of Seward the United States Senate approved the purchase, known as the Alaska Purchase, from the Russian Empire. The cost was set at 2 cents an acre, which came to a total of $7,200,000 on April 9, 1867. The canceled check is in the present day United States National Archives.

After Russian America was sold to the U.S. in 1867, for $7.2 million (2 cents per acre, equivalent to $119٬725٬714 in 2022), all the holdings of the Russian–American Company were liquidated.

Following the transfer, many elders of the local Tlingit tribe maintained that "Castle Hill" comprised the only land that Russia was entitled to sell. Other indigenous groups also argued that they had never given up their land; the Americans had encroached on it and taken it over. Native land claims were not fully addressed until the latter half of the 20th century, with the signing by Congress and leaders of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

At the height of Russian America, the Russian population had reached 700, compared to 40,000 Aleuts. They and the Creoles, who had been guaranteed the privileges of citizens in the United States, were given the opportunity of becoming citizens within a three-year period, but few decided to exercise that option. General Jefferson C. Davis ordered the Russians out of their homes in Sitka, maintaining that the dwellings were needed for the Americans. The Russians complained of rowdiness of and assaults by the American troops. Many Russians returned to Russia, while others migrated to the Pacific Northwest and California.

Legacy

The Soviet Union (USSR) released a series of commemorative coins in 1990 and 1991 to mark the 250th anniversary of the first sighting of and claiming domain over Alaska–Russian America. The commemoration consisted of a silver coin, a platinum coin, and two palladium coins in both years.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a resurgence of Russian ultra-nationalism has spurred regret and recrimination over the sale of Alaska to the United States.[9][10][11] There are periodic mass media stories in the Russian Federation that Alaska was not sold to the United States in the 1867 Alaska Purchase, but only leased for 99 years (= to 1966), or 150 years (= to 2017)—and would be returned to Russia.[12] During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, such statements reappeared in Russian media. Those claims of illegitimacy derive from wrong or misleading interpretations of a policy of the Russian Federation to re-acquire formerly held properties.[13] The Alaska Purchase Treaty clearly states that the agreement was for a complete Russian cession of the territory.[14][15] The Alaskan Native peoples, in their struggle for democracy and indigenous rights, take issue with the legitimacy of colonial rule itself rather than the purchase from the Russian Empire.[16]

المستوطنات الروسية في أمريكا الشمالية

- Unalaska, Alaska – 1774

- Three Saints Bay, Alaska – 1784

- Fort St. George in Kasilof, Alaska – 1786[بحاجة لمصدر]

- St. Paul, Alaska – 1788

- Fort St. Nicholas in Kenai, Alaska – 1791[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Pavlovskaya, Alaska (now Kodiak) – 1791

- Fort Saints Constantine and Helen on Nuchek Island, Alaska – 1793[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Fort on Hinchinbrook Island, Alaska – 1793[بحاجة لمصدر]

- New Russia near present-day Yakutat, Alaska – 1796

- Redoubt St. Archangel Michael, Alaska near Sitka – 1799

- Novo-Arkhangelsk, Alaska (now Sitka) – 1804

- Fort Ross, California – 1812

- Fort Elizabeth near Waimea, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Alexander near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Barclay-de-Tolly near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Fort (New) Alexandrovsk at Bristol Bay, Alaska – 1819[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Kolmakov Redoubt, Alaska – 1832

- Redoubt St. Michael, Alaska – 1833

- Nulato, Alaska – 1834

- Redoubt St. Dionysius in present-day Wrangell, Alaska (now Fort Stikine) – 1834

- Pokrovskaya Mission, Alaska – 1837

- Ninilchik, Alaska – 1847

انظر أيضاً

الأمريكان الأصليون

الروس

- قائمة المستكشفين الروس

- Herman of Alaska

- Mikhail Tebenkov

- Johan Hampus Furuhjelm

- Nikolai Rezanov

- Vitus Bering

تاريخ

- الاستعمار الروسي

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- التجريدة الشمالية الكبرى

- California Fur Rush

- Awa'uq Massacre

- Russo-American Treaty of 1824

- تاريخ الساحل الغربي لأمريكا الشمالية

- الاستعمار الروسي للأمريكتين

- التلغراف الأمريكي الروسي

مواضيع أخرى

الهامش

- ^ Charles P. Wohlforth (2011). Alaska For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 18.

- ^ United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, "Text of Ukase of 1779" in Behring Sea Arbitration (London: Harrison and Sons, 1893), pp. 25–27

- ^ Sergei, Kan (2014). Memory Eternal: Tlingit Culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity Through Two Centuries. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295805344. OCLC 901270092.

- ^ Campbell, Robert (2007). In Darkest Alaska: Travel and Empire Along the Inside Passage. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8122-4021-4.

- ^ Black, Lydia T. (2004). Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- ^ ""The People You May Visit"". Russia's Great Voyages. California Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 13 April 2003. Retrieved 23 September 2005.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Nordlander, David (1995). "Innokentii Veniaminov and the Expansion of Orthodoxy in Russian America". Pacific Historical Review. 64 (1): 19–35. doi:10.2307/3640333. JSTOR 3640333.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Kan, Sergei (1985). "Russian Orthodox Brotherhoods among the Tlingit: Missionary Goals and Native Response". Ethnohistory. 32 (3): 196–222. doi:10.2307/481921. JSTOR 481921.

- ^ Nelson, Soraya Sarhaddi (April 1, 2014). "Not An April Fools' Joke: Russians Petition To Get Alaska Back". NPR. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Tetrault-Farber, Gabrielle (March 31, 2014). "After Crimea, Russians Say They Want Alaska Back". The Moscow Times. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Gershkovich, Evan (March 30, 2017). "150 Years After Sale of Alaska, Some Russians Have Second Thoughts". The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Haycox, Steve (May 18, 2017). "Russian extremists want Alaska back". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Stepanova, Alexandra (January 31, 2024). "Analysis: Russian decree on its assets overseas (no, Alaska was not mentioned)". annie lab. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Metcalfe, Peter (August 24, 2017). "The Purchase of Alaska: 1867 or 1971". Alaska Historical Society - Dedicated to the promotion of Alaska history by the exchange of ideas and information. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ "Transcription of the English text of the Alaska Treaty of Cession". Our Documents. The United States National Archives. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "There Are Two Versions of the Story of How the U.S. Purchased Alaska From Russia". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. March 29, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

للاستزادة

- Black, Lydia T. (2004). Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 978-1-889963-05-1.

- Black, Lydia T.; Dauenhauer, Nora; Dauenhauer, Richard (2008). Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98601-2.

- Essig, Edward Oliver. Fort Ross: California Outpost of Russian Alaska, 1812–1841 (Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press, 1991.)

- Frost, Orcutt (2003). Bering: The Russian Discovery of America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10059-4.

- Gibson, James R. "Old Russia in the New World: adversaries and adversities in Russian America." in European Settlement and Development in North America (University of Toronto Press, 2019) pp. 46–65.

- Gibson, James R. Imperial Russia in frontier America: the changing geography of supply of Russian America, 1784–1867 (Oxford University Press, 1976)

- Gibson, James R. "Russian America in 1821." Oregon Historical Quarterly (1976): 174–188. online

- Grinev, Andrei Valterovich (2008). The Tlingit Indians in Russian America, 1741–1867. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2071-3.

- Grinëv, Andrei Val’terovich. "The External Threat to Russian America: Myth and Reality." Journal of Slavic Military Studies 30.2 (2017): 266–289.

- Grinëv, Andrei Val’terovich. Russian Colonization of Alaska: Preconditions, Discovery, and Initial Development, 1741–1799 Translated by Richard L. Bland. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018. ISBN 978-1-4962-0762-3. online review

- Kobtzeff, Oleg (1985). La Colonization russe en Amérique du Nord: 18 - 19 ème siècles [Russian Colonization in North America, 18th-19th Centuries] (in الفرنسية). Paris: thesis, University of Paris 1 - Panthéon Sorbonne (available in limited editions in specialized libraries).

- Miller, Gwenn A. (2010). Kodiak Kreol: Communities of Empire in Early Russian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4642-9.

- Oleksa, Michael J. (1992). Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission. Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-092-1.

- Oleksa, Michael J., ed. (2010). Alaskan Missionary Spirituality (2nd ed.). Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-340-3.

- Pierce, Richard A. Russian America, 1741–1867: A Biographical Dictionary (Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press, 1990)

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (1987). Russia's American Colony. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0688-7.

- Saul, Norman E. "Empire Maker: Aleksandr Baranov and Russian Colonial Expansion into Alaska and Northern California." Journal of American Ethnic History 36.3 (2017): 91–93.

- Saul, Norman. "California-Alaska trade, 1851–1867: The American Russian commercial company and the Russian America company and the sale/purchase of Alaska." Journal of Russian American Studies 2.1 (2018): 1–14. online

- Vinkovetsky, Ilya (2011). Russian America: An Overseas Colony of a Continental Empire, 1804–1867. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539128-2.

Natives

- Grinëv, Andrei V. "Natives and Creoles of Alaska in the maritime service in Russian America." The Historian 82.3 (2020): 328–345. online[dead link]

- The Tlingit Indians in Russian America, 1741–1867, Andreĭ Valʹterovich Grinev (GoogleBooks)

- Luehrmann, Sonja. Alutiiq villages under Russian and US rule (University of Alaska Press, 2008.)

- Smith-Peter, Susan (2013). ""A Class of People Admitted to the Better Ranks": The First Generation of Creoles in Russian America, 1810s–1820s". Ethnohistory. 60 (3): 363–384. doi:10.1215/00141801-2140758.

- Savelev, Ivan. "Patterns in the Adoption of Russian Linguistic and National Traditions by Alaskan Natives." International Conference on European Multilingualism: Shaping Sustainable Educational and Social Environment EMSSESE, 2019. (Atlantis Press, 2019). online

Primary sources

- Gibson, James R. (1972). "Russian America in 1833: The Survey of Kirill Khlebnikov". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 63 (1): 1–13. JSTOR 40488966.

- Golovin, Pavel Nikolaevich, Basil Dmytryshyn, and E. A. P. Crownhart-Vaughan. The end of Russian America: Captain PN Golovin's last report, 1862(Oregon Historical Society Press, 1979.)

- Khlebnikov, Kyrill T. Colonial Russian America: Kyrill T. Khlebnikov's Reports, 1817–1832 (Oregon Historical Society, 1976)

- baron Wrangel, Ferdinand Petrovich. Russian America: Statistical and ethnographic information (Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press, 1980)

Historiography

- Grinëv, Andrei. V.; Bland, Richard L. (2010). "A Brief Survey of the Russian Historiography of Russian America of Recent Years" (PDF). Pacific Historical Review. 79 (2): 265–278. doi:10.1525/phr.2010.79.2.265. JSTOR 10.1525/phr.2010.79.2.265.[dead link]

External links

- The Russian-American Treaty of 1867

- Official Website of Fort Ross State Historic Park

- Fort Ross Cultural History Fort Ross Interpretive Association

]

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Former country articles requiring maintenance

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2023

- Portal templates with default image

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Articles with dead external links from July 2022

- Articles with dead external links from May 2024

- Russian colonization of North America

- Colonization history of the United States

- European colonization of North America

- Subdivisions of the Russian Empire

- Fur trade

- Pre-Confederation British Columbia

- History of Yukon

- Pre-statehood history of Alaska

- Pre-statehood history of California

- History of European colonialism

- Overseas empires

- Russian exploration in the Age of Discovery

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- History of colonialism

- Colonialism

- أمريكا الروسية

- تاريخ استعمار الولايات المتحدة

- استعمار الأمريكتين

- تقسيمات الامبراطورية الروسية

- انحلالات 1867

- تاريخ الشمال الغربي الهادي

- تاريخ الساحل الغربي للولايات المتحدة

- تاريخ ألاسكا قبل الولاية

- تاريخ كلومبيا البريطانية

- تاريخ كاليفورنيا قبل الولاية

- تاريخ كاوائي

- مملكة هاوائي

- تجارة الفراء