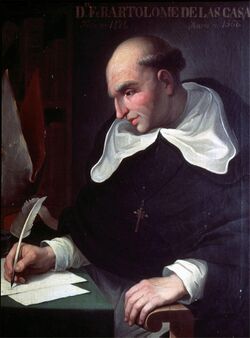

بارتولومى دى لاس كاساس

| The Right Reverend Friar and Servant of God Fray Bartolomé de las Casas O.P. | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Chiapas | |

| |

| المقاطعة | Tuxtla Gutiérrez |

| انظر | Chiapas |

| اعتلى السـُدة | 13 March 1544 |

| انتهى سـُدته | 11 September 1550 |

| التكريس | 1510 |

| الترسيم | 30 March 1554 |

| غيرهم | Protector of the Indians |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| اسم الميلاد | Bartolomé de las Casas |

| وُلِد | 11 November 1484 Seville, Crown of Castile |

| توفي | 18 July 1566 (aged 81) Madrid, Crown of Spain |

| دُفِن | Basilica of Our Lady of Atocha, Madrid, Spain |

| الجنسية | Spanish |

| الطائفة | Roman Catholic |

| الوظيفة | Hacienda owner, priest, missionary, bishop, writer |

| التوقيع |  |

| Sainthood | |

| يوم عيده | 18 July |

| مبجل في | The Episcopal Church (USA); The Roman Catholic Church |

| لقبه كقديس | Servant of God |

بارتولومي دي لاس كاساس ( Bartolomé de las Casas ؛ الأمريكي /lɑːs ˈkɑːsəs/ lahs KAH-səs; النطق الإسپاني: [baɾtoloˈme ðe las ˈkasas]؛ 11 نوفمبر 1484[1] – 18 يوليو 1566) راهب كان صوت الهنود والسكان الاصليين للامريكتين عارض استعباد الهنود وكانوا يعتبرونه ضد الأسياد الجدد للمستعمرين وكان يعترض استخدام الدين والمسيح إلى أله أكثر قسوة والملك الي دب جائع للحم البشر. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar and priest. He was appointed as the first resident Bishop of Chiapas, and the first officially appointed "Protector of the Indians". His extensive writings, the most famous being A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies and Historia de Las Indias, chronicle the first decades of colonization of the West Indies. He described the atrocities committed by the colonizers against the indigenous peoples.[2]

Arriving as one of the first Spanish (and European) settlers in the Americas, Las Casas initially participated in, but eventually felt compelled to oppose, the abuses committed by colonists against the Native Americans.[3] As a result, in 1515 he gave up his Indian slaves and encomienda, and advocated, before King Charles I of Spain, on behalf of rights for the natives. In his early writings, he advocated the use of African slaves instead of Natives in the West Indian colonies but did so without knowing that the Portuguese were carrying out "brutal and unjust wars in the name of spreading the faith".[4] Later in life, he retracted this position, as he regarded both forms of slavery as equally wrong.[5] In 1522, he tried to launch a new kind of peaceful colonialism on the coast of Venezuela, but this venture failed. Las Casas entered the Dominican Order and became a friar, leaving public life for a decade. He traveled to Central America, acting as a missionary among the Maya of Guatemala and participating in debates among colonial churchmen about how best to bring the natives to the Christian faith.

Travelling back to Spain to recruit more missionaries, he continued lobbying for the abolition of the encomienda, gaining an important victory by the passage of the New Laws in 1542. He was appointed Bishop of Chiapas, but served only for a short time before he was forced to return to Spain because of resistance to the New Laws by the encomenderos, and conflicts with Spanish settlers because of his pro-Indian policies and activist religious stance. He served in the Spanish court for the remainder of his life; there he held great influence over Indies-related issues. In 1550, he participated in the Valladolid debate, in which Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda argued that the Indians were less than human, and required Spanish masters to become civilized. Las Casas maintained that they were fully human, and that forcefully subjugating them was unjustifiable.

Bartolomé de las Casas spent 50 years of his life actively fighting slavery and the colonial abuse of indigenous peoples, especially by trying to convince the Spanish court to adopt a more humane policy of colonization. Unlike some other priests who sought to destroy the indigenous peoples' native books and writings, he strictly opposed this action.[6] Although he did not completely succeed in changing Spanish views on colonization, his efforts did result in improvement of the legal status of the natives, and in an increased colonial focus on the ethics of colonialism.

في عام 1571 قام الملك فليب الثاني بحرق كتب الراهب حتي لا تقع في يد احد ، ويوجد نسخةواحدة من كتابة تاريخ الانديز السميك جدا في أبرشية سان گريگوريو.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

حياته وزمنه

خلفية ووصوله العالم الجديد

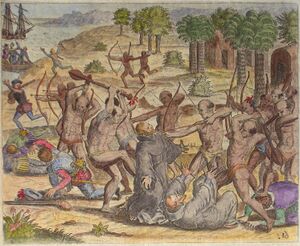

Depiction of Spanish atrocities committed in the conquest of Cuba in Las Casas's "Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias". The print was made by two Flemish artists who had fled the Southern Netherlands because of their Protestant faith: Joos van Winghe was the designer and Theodor de Bry the engraver. |

Bartolomé de las Casas was born in Seville in 1484, on 11 November.[7] For centuries, Las Casas's birthdate was believed to be 1474; however, in the 1970s, scholars conducting archival work demonstrated this to be an error, after uncovering in the Archivo General de Indias records of a contemporary lawsuit that demonstrated he was born a decade later than had been supposed.[8] Subsequent biographers and authors have generally accepted and reflected this revision.[9] His father, Pedro de las Casas, a merchant, descended from one of the families that had migrated from France to found the Christian Seville; his family also spelled the name Casaus.[10] According to one biographer, his family was of converso heritage,[11] although others refer to them as ancient Christians who migrated from France.[10] Following the testimony of Las Casas's biographer Antonio de Remesal, tradition has it that Las Casas studied a licentiate at Salamanca, but this is never mentioned in Las Casas's own writings.[12] As a young man, in 1507, he journeyed to Rome where he observed the Festival of Flutes.[13]

With his father, Las Casas immigrated to the island of Hispaniola in 1502, on the expedition of Nicolás de Ovando. Las Casas became a hacendado and slave owner, receiving a piece of land in the province of Cibao.[14] He participated in slave raids and military expeditions against the native Taíno population of Hispaniola.[15] In 1510, he was ordained a priest, the first one to be ordained in the Americas.[16][17]

In September 1510, a group of Dominican friars arrived in Santo Domingo led by Pedro de Córdoba; appalled by the injustices they saw committed by the slaveowners against the Indians, they decided to deny slave owners the right to confession. Las Casas was among those denied confession for this reason.[18] In December 1511, a Dominican preacher Fray Antonio de Montesinos preached a fiery sermon that implicated the colonists in the genocide of the native peoples. He is said to have preached, "Tell me by what right of justice do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged such detestable wars against these people who dealt quietly and peacefully on their own lands? Wars in which you have destroyed such an infinite number of them by homicides and slaughters never heard of before. Why do you keep them so oppressed and exhausted, without giving them enough to eat or curing them of the sicknesses they incur from the excessive labor you give them, and they die, or rather you kill them, in order to extract and acquire gold every day."[19] Las Casas himself argued against the Dominicans in favour of the justice of the encomienda. The colonists, led by Diego Columbus, dispatched a complaint against the Dominicans to the King, and the Dominicans were recalled from Hispaniola.[20][21]

Conquest of Cuba and change of heart

In 1513, as a chaplain, Las Casas participated in Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar's and Pánfilo de Narváez' conquest of Cuba. He participated in campaigns at Bayamo and Camagüey and in the massacre of Hatuey.[22] He witnessed many atrocities committed by Spaniards against the native Ciboney and Guanahatabey peoples. He later wrote: "I saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see."[23] Las Casas and his friend Pedro de la Rentería were awarded a joint encomienda which was rich in gold and slaves, located on the Arimao River close to Cienfuegos. During the next few years, he divided his time between being a colonist and his duties as an ordained priest.

In 1514, Las Casas was studying a passage in the book Ecclesiasticus (Sirach)[24] 34:18–22[أ] for a Pentecost sermon and pondering its meaning. Las Casas was finally convinced that all the actions of the Spanish in the New World had been illegal and that they constituted a great injustice. He made up his mind to give up his slaves and encomienda, and started to preach that other colonists should do the same. When his preaching met with resistance, he realized that he would have to go to Spain to fight there against the enslavement and abuse of the native people.[25] Aided by Pedro de Córdoba and accompanied by Antonio de Montesinos, he left for Spain in September 1515, arriving in Seville in November.[26][27]

Las Casas and King Ferdinand

Las Casas arrived in Spain with the plan of convincing the King to end the encomienda system. This was easier thought than done, as most of the people who were in positions of power were themselves either encomenderos or otherwise profiting from the influx of wealth from the Indies.[28] In the winter of 1515, King Ferdinand lay ill in Plasencia, but Las Casas was able to get a letter of introduction to the king from the Archbishop of Seville, Diego de Deza. On Christmas Eve of 1515, Las Casas met the monarch and discussed the situation in the Indies with him; the king agreed to hear him out in more detail at a later date. While waiting, Las Casas produced a report that he presented to the Bishop of Burgos, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, and secretary Lope Conchillos, who were functionaries in complete charge of the royal policies regarding the Indies; both were encomenderos. They were not impressed by his account, and Las Casas had to find a different avenue of change. He put his faith in his coming audience with the king, but it never came, for King Ferdinand died on 25 January 1516.[29] The regency of Castile passed on to Ximenez Cisneros and Adrian of Utrecht who were guardians for the under-age Prince Charles. Las Casas was resolved to see Prince Charles who resided in Flanders, but on his way there he passed Madrid and delivered to the regents a written account of the situation in the Indies and his proposed remedies. This was his "Memorial de Remedios para Las Indias" of 1516.[30] In this early work, Las Casas advocated importing black slaves from Africa to relieve the suffering Indians, a stance he later retracted, becoming an advocate for the Africans in the colonies as well.[31][32][33][ب] This shows that Las Casas's first concern was not to end slavery as an institution, but to end the physical abuse and suffering of the Indians.[34] In keeping with the legal and moral doctrine of the time Las Casas believed that slavery could be justified if it was the result of Just War, and at the time he assumed that the enslavement of Africans was justified.[35] Worried by the visions that Las Casas had drawn up of the situation in the Indies, Cardinal Cisneros decided to send a group of Hieronymite monks to take over the government of the islands.[36]

Protector of the Indians

Three Hieronymite monks, Luis de Figueroa, Bernardino de Manzanedo, and Alonso de Santo Domingo, were selected as commissioners to take over the authority of the Indies. Las Casas had a considerable part in selecting them and writing the instructions under which their new government would be instated, largely based on Las Casas's memorial. Las Casas himself was granted the official title of Protector of the Indians, and given a yearly salary of one hundred pesos. In this new office Las Casas was expected to serve as an advisor to the new governors with regard to Indian issues, to speak the case of the Indians in court, and send reports back to Spain. Las Casas and the commissioners traveled to Santo Domingo on separate ships, and Las Casas arrived two weeks later than the Hieronimytes. During this time the Hieronimytes had time to form a more pragmatic view of the situation than the one advocated by Las Casas; their position was precarious as every encomendero on the Islands was fiercely against any attempts to curtail their use of native labour. Consequently, the commissioners were unable to take any radical steps towards improving the situation of the natives. They did revoke some encomiendas from Spaniards, especially those who were living in Spain and not on the islands themselves; they even repossessed the encomienda of Fonseca, the Bishop of Burgos. They also carried out an inquiry into the Indian question at which all the encomenderos asserted that the Indians were quite incapable of living freely without their supervision. Las Casas was disappointed and infuriated. When he accused the Hieronymites of being complicit in kidnapping Indians, the relationship between Las Casas and the commissioners broke down. Las Casas had become a hated figure by Spaniards all over the islands, and he had to seek refuge in the Dominican monastery. The Dominicans had been the first to indict the encomenderos, and they continued to chastise them and refuse the absolution of confession to slave owners, and even stated that priests who took their confession were committing a mortal sin. In May 1517, Las Casas was forced to travel back to Spain to denounce to the regent the failure of the Hieronymite reforms.[37] Only after Las Casas had left did the Hieronymites begin to congregate Indians into towns similar to what Las Casas had wanted.[38]

Las Casas and Emperor Charles V: The peasant colonization scheme

When he arrived in Spain, his former protector, regent, and Cardinal Ximenez Cisneros, was ill and had become tired of Las Casas's tenacity. Las Casas resolved to meet instead with the young king Charles I. Ximenez died on 8 November, and the young King arrived in Valladolid on 25 November 1517. Las Casas managed to secure the support of the king's Flemish courtiers, including the powerful Chancellor Jean de la Sauvage. Las Casas's influence turned the favor of the court against Secretary Conchillos and Bishop Fonseca. Sauvage spoke highly of Las Casas to the king, who appointed Las Casas and Sauvage to write a new plan for reforming the governmental system of the Indies.[39]

Las Casas suggested a plan where the encomienda would be abolished and Indians would be congregated into self-governing townships to become tribute-paying vassals of the king. He still suggested that the loss of Indian labor for the colonists could be replaced by allowing importation of African slaves. Another important part of the plan was to introduce a new kind of sustainable colonization, and Las Casas advocated supporting the migration of Spanish peasants to the Indies where they would introduce small-scale farming and agriculture, a kind of colonization that didn't rely on resource depletion and Indian labor. Las Casas worked to recruit a large number of peasants who would want to travel to the islands, where they would be given lands to farm, cash advances, and the tools and resources they needed to establish themselves there. The recruitment drive was difficult, and during the process the power relation shifted at court when Chancellor Sauvage, Las Casas's main supporter, unexpectedly died. In the end a much smaller number of peasant families were sent than originally planned, and they were supplied with insufficient provisions and no support secured for their arrival. Those who survived the journey were ill-received, and had to work hard even to survive in the hostile colonies. Las Casas was devastated by the tragic result of his peasant migration scheme, which he felt had been thwarted by his enemies. He decided instead to undertake a personal venture which would not rely on the support of others, and fought to win a land grant on the American mainland which was in its earliest stage of colonization.[40]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

مشروع كومانا

مناظرة بلد الوليد

السنوات اللاحقة والوفاة

ذكراه

الذكرى الثقافية

مصادر

- انظر كتاب سفر التكوين ص 131 للكاتب إدواردو گاليانو، ترجمة أسامة اسبر.

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ "If one sacrifices from what has been wrongfully obtained, the offering is blemished; the gifts of the lawless are not acceptable. ... Like one who kills a son before his father's eyes is the man who offers sacrifice from the property of the poor. The bread of the needy is the life of the poor; whoever deprives them of it is a man of blood." quoted from Brading (1997:119–20).

- ^ Las Casas's retraction of his views on African slavery is expressed particularly in chapters 102 and 129, Book III of his Historia.

Citations

- ^ Parish & Weidman (1976)

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1997). The Zinn Reader. Seven Stories Press. p. 483. ISBN 978-1-583229-46-0.

- ^ "July 2015: Bartolomé de las Casas and 500 Years of Racial Injustice | Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective". origins.osu.edu. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- ^ Lantigua, David. "7 – Faith, Liberty, and the Defense of the Poor: Bishop Las Casas in the History of Human Right", Hertzke, Allen D., and Timothy Samuel Shah, eds. Christianity and Freedom: Historical Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, 2016, 190.

- ^ Clayton, Lawrence (2009). "Bartolomé de las Casas and the African Slave Trade". History Compass (in الإنجليزية). 7 (6): 1532. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00639.x. ISSN 1478-0542.

On advocating the importation of a slaves back in 1516, Las Casas wrote 'the cleric [he often wrote in the third person], many years later, regretted the advice he gave the king on this matter—he judged himself culpable through inadvertence—when he saw proven that the enslavement of blacks was every bit as unjust as that of the Indians...

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 136.

- ^ Parish & Weidman (1976:385)

- ^ Parish & Weidman (1976, passim)

- ^ e.g. Saunders (2005:162)

- ^ أ ب Wagner & Parish (1967:1–3)

- ^ Giménez Fernández (1971:67)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:4)

- ^ Giménez Fernández (1971:71–72)

- ^ Giménez Fernández (1971:72)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:5)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:6)

- ^ Baptiste (1990:7)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:11)

- ^ Witness: Writing of Bartolome de Las Casas. Edited and translated by George Sanderlin (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1993), 66–67

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:8–9)

- ^ Wynter (1984a:29–30)

- ^ Giménez Fernández (1971:73)

- ^ Indian Freedom: The Cause of Bartolome de las Casas. Translated and edited by Sullivan (1995:146)

- ^ Ecclesiasticus, Encyclopædia Britannica online

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:11–13)

- ^ Baptiste (1990:69)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:13–15)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:15)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:15–17)

- ^ Baptiste (1990:7–10)

- ^ Wynter (1984a), Wynter (1984b)

- ^ Blackburn (1997:136)

- ^ Friede (1971:165–66)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:23)

- ^ Wynter (1984a)

- ^ "Figueroa, fray Luis de (¿-1523). » MCNBiografias.com". www.mcnbiografias.com.

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:25–30)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:33)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:35–38)

- ^ Wagner & Parish (1967:38–45)

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Las Casas in Baptiste 1990 p14" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Historia Apologetica, Wagner & Parish 1967" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Historia de las Indias, 5 volumes" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Historia de Las Indias, vol 1" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Walker's Appeal" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Las Casas Institute" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "McBrien" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

<ref> ذو الاسم "Frayba" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.References

- Alcedo, Antonio de (1786). Diccionario geográfico-histórico de las Indias Occidentales ó América: es á saber: de los reynos del Perú, Nueva España, Tierra Firme, Chile, y Nuevo reyno de Granada (in الإسبانية). Vol. vol. 1. Madrid: Benito Cano. OCLC 2414115.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Baptiste, Victor N. (1990). Bartolomé de las Casas and Thomas More's Utopia: Connections and Similarities. Labyrinthos. ISBN 978-0-911437-43-0. OCLC 246823100.

- Blackburn, Robin (1997). The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492–1800 (1st Verso pbk [1998 printing] ed.). London: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-85984-195-2. OCLC 40130171.

- Boruchoff, David A. (2008). "Another Face of Empire: Bartolomé de las Casas, Indigenous Rights, and Ecclesiastical Imperialism (review)". Early American Literature. 43 (2): 497–504. doi:10.1353/eal.0.0014. S2CID 162314664.

- Brading, David (1997). "Prophet and apostle: Bartolomé de las Casas and the spiritual conquest of America". In Cummins, J. S. (ed.). Christianity and Missions, 1450–1800. An Expanding World: The European Impact on World History, 1450–1800 [Ashgate Variorum series]. Vol. vol. 28. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 117–38. ISBN 978-0-86078-519-4. OCLC 36130668.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Carozza, Paolo G. (2003). "From Conquest to Constitutions: Retrieving a Latin American Tradition of the Idea of Human Rights" (PDF). Human Rights Quarterly. 25 (2): 281–313. doi:10.1353/hrq.2003.0023. S2CID 145420134. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06.

- Castro, Daniel (2007). Another Face of Empire. Duke University Press.

- Comas, Juan (1971). "Historical reality and the detractors of Father Las Casas". In Friede, Juan; Keen, Benjamin (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 487–539. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. OCLC 421424974.

- Friede, Juan (1971). "Las Casas and Indigenism in the Sixteenth Century". In Friede, Juan; Keen, Benjamin (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 127–234. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. OCLC 421424974.

- Giménez Fernández, Manuel (1971). "Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas: A Biographical Sketch". In Friede, Juan; Keen, Benjamin (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 67–126. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. OCLC 421424974.

- Glendon, Mary Ann (2003). "The Forgotten Crucible: The Latin American Influence on the Universal Human Rights Idea". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 16.

- Guitar, Lynne (1997). "Encomienda System". In Rodriguez, Junius P. (ed.). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. Vol. 1, A–K. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 250–51. ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7. OCLC 37884790.

- Gunst, Laurie. "Bartolomé de las Casas and the Question of Negro Slavery in the Early Spanish Indies." PhD dissertation, Harvard University 1982.

- Hanke, Lewis (1951). Bartolomé de Las Casas: An interpretation of his life and writings. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Hanke, Lewis (1952). Bartolomé de Las Casas: Bookman, Scholar & Propagandist. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jay, Felix (2002). Bartolomé de Las Casas (1474–1566) in the pages of Father Antonio de Remesal. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-7131-3.

- Keen, Benjamin (1971). "Introduction: Approaches to Las Casas, 1535–1970". In Friede, Juan; Keen, Benjamin (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 67–126. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. OCLC 421424974.

- Keen, Benjamin (1969). "The Black Legend Revisited: Assumptions and Realities". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 49 (4): 703–19. doi:10.2307/2511162. JSTOR 2511162.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de (1997). "Apologetic History of the Indies". Columbia University Sources of Medieval History.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) From Apologética historia de las Indias (Madrid, 1909), originally translated for Introduction to Contemporary Civilization in the West (New York: Columbia University Press, 1946, 1954, 1961). - Losada, Ángel (1971). "Controversy between Sepúlveda and Las Casas". In Friede, Juan; Keen, Benjamin (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 279–309. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. OCLC 421424974.

- MacNutt, Francis Augustus (1909). Bartholomew de Las Casas: His Life, Apostolate, and Writings (PDF online reproduction) (Project Gutenberg EBook no. 23466, reproduction ed.). Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark. OCLC 2683160.

- Orique, David T. (2009). "Journey to the Headwaters: Bartolomé de Las Casas in a Comparative Context". The Catholic Historical Review. 95 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1353/cat.0.0312. S2CID 159905806.

- Parish, Helen Rand; Weidman, Harold E. (1976). "The Correct Birthdate of Bartolomé de las Casas". Hispanic American Historical Review. 56 (3): 385–403. doi:10.2307/2514372. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2514372. OCLC 1752092.

- Pierce, Brian (1992). "Bartolomé de las Casas and Truth: Toward a Spirituality of Solidarity". Spirituality Today. 44 (1): 4–19. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29.

- Rand-Parish, Helen (1980). Las Casas as Bishop: A new interpretation based on his holograph petition in the Hans P. Kraus Collection of Hispanic American Manuscripts. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

- Rand-Parish, Helen; Weidman, Harold E. (1980). Las Casas en Mexico: Historia y obra desconocidas. Ciudad de Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Rand-Parish, Helen; Gutiérrez, Gustavo (1984). Bartolomé de las Casas: Liberation of the Oppressed. Berkeley.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rubiés, Joan-Pau (2007). "Another face of empire. Bartolomé de Las Casas, indigenous rights, and ecclesiastical imperalism. By Daniel Castro. (Latin America Otherwise. Languages, Empires, Nations.) Pp. Xii+234. Durham–London: Duke University Press, 2007. £53 (cloth), £13.99 (paper). 978 0 8223 3930 4; 978 0 8223 3939 7" (PDF). The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 58 (4): 767–68. doi:10.1017/S0022046907001704.

- Saunders, Nicholas J. (2005). Peoples of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archeology and Traditional Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-701-6. OCLC 62090786.

- Sullivan, Patrick Francis, ed. (1995). Indian Freedom: The Cause of Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484–1566, A Reader. Kansas City, Missouri: Sheed and Ward.

- Tierney, Brian (1997). The Idea of Natural Rights: Studies on Natural Rights, Natural Law and Church Law 1150–1625. Scholar's Press for Emory University. pp. 272–74.

- Wagner, Henry Raup; Parish, Helen Rand (1967). The Life and Writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas. University of New Mexico Press.

- Wynter, Sylvia (1984a). "New Seville and the Conversion Experience of Bartolomé de Las Casas: Part One". Jamaica Journal. 17 (2): 25–32.

- Wynter, Sylvia (1984b). "New Seville and the Conversion Experience of Bartolomé de Las Casas: Part Two". Jamaica Journal. 17 (3): 46–55.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

وصلات خارجية

- Biblioteca de autor Bartolomé de las Casas (in إسپانية)

- أعمال من بارتولومى دى لاس كاساس في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- Works by or about بارتولومى دى لاس كاساس at Internet Archive

- Works by بارتولومى دى لاس كاساس at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Bartolomé de Las Casas Study Resources

- Mirror of the Cruel and Horrible Spanish Tyranny Perpetrated in the Netherlands, by the Tyrant, the Duke of Alba, and Other Commanders of King Philip II From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Bartolomé de las Casas Statement of Opinion, (1542.) From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Narratio Regionum Indicarum per Hispanos Quosdam Deuastatarum Verissima From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Las Casas' Articulation of the Indians' Moral Agency: Looking Back at Las Casas Through Fichte--Rolando Pérez.

| ألقاب الكنيسة الكاثوليكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Juan de Arteaga y Avendaño |

Bishop of Chiapas 19 Dec 1543 – 11 Sep 1550 Resigned |

تبعه Tomás Casillas, O.P. |

خطأ لوا في package.lua على السطر 80: module 'Module:Authority control/auxiliary' not found.

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles with إسپانية-language sources (es)

- مقالات جيدة

- مواليد 1484

- وفيات 1566

- 16th-century historians

- 16th-century Mesoamericanists

- 16th-century Roman Catholic bishops in Mexico

- 16th-century Spanish writers

- 16th-century male writers

- Abolitionism in South America

- Roman Catholic missionaries in New Spain

- People of the Colony of Santo Domingo

- Dominican bishops

- Encomenderos

- Historians of Mesoamerica

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- أشخاص من اشبيلية

- Philosophers of law

- Roman Catholic activists

- Roman Catholic writers

- Spanish Dominicans

- Spanish historians

- Spanish human rights activists

- Spanish Mesoamericanists

- University of Salamanca alumni

- History of Chiapas

- School of Salamanca

- Anglican saints