علم الوراثة العرقي

| جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

| علم الأحياء التطوري |

|---|

|

|

بوابة التطور تصنيف • مقالات متعلقة • كتب |

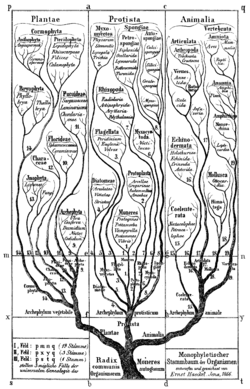

علم الوراثة العرقي أو تطور السلالة Phylogenetics، هو عملية تغير وحدة تصنيفية (نوع أو جنس أو عائلة أو غيرها) خلال الزمن الجيولوجي، أي تاريخ تطور مجموعة شاملة collective group.[1] وهو دراسة التاريخ التطوري والعلاقات بين أفراد أو مجموعات العضيات (مثل الأنواع أو الجماعات). أُكتشفت هذه العلاقات عن طريق منهجيات الاستدلال الوراثي العرقي التي تقيم السمات المورثة، مثل تسلسل الدنا أو المورفولوجيا تحت نموذج تطور هذه السمات. ناتج هذه التحليل هو الشجرة الوراثية العرقية (تعرف أيضاً بشجرة المحتد)- فرضية تخطيطية عن تاريخ العلاقات التطورية لمجموعة من العضيات.[2] قد ترشد معلومات الشجرة التطورية إلى حياة العضيات أو الأحفورات، وتمثل "النهاية"، أو الحاضر، في النسب التطوري. أصبح التحليل الوراثي العرقي مركزاً لفهم التنوع الحيوي، التطور، علم البيئة، والجينوم.

التصنيف هو تعريف، تسمية وتصنيف العضيات. عادة ما يستمد معلوماته الوفيرة من علم الوراثة العرقي، لكنه يظل تخصصاً متميزاً منطقياً ومنهجياً.[3] درجة التصنيفات المعتمدة على الأشجار التطورية (أو يعتمد التصنيف على التنمية التطورية) تختلف تبعاً لمدرسة التصنيف: phenetics تتجاهل الوراثة العرقية تماماً، حيث تحاول بدلاً من ذلك تمثيل التشابه بين العضيات؛ علم شجرة الحياة يحاول اعادة إنتاج الوراثة التطورية ضمن تصنيفاتها بدون خسارة المعلومات؛ ويحاول التصنيف التطوري إيجاد حلاً وسطاً بينهم.

بناء شجرة الأنساب

الطرق المعتادة للاستدلال الوراثي العرقي تتضمن منهجيات حسابية تطبق المعايير المثلى وطرق parsimony، الاحتمال الأرجح (ML)، واستدلال بايزي المعتمد على MCMC. جميع هذه المنهجيات تعتمد على نموذج رياضياتي ضمني أو صريح يصف تطور الشخصيات الملحوظ.

Phenetics، التي اشتهرت في منتصف القرن 20 لكن الآن عفا عليها الزمن بشكل كبير، استخدمت المنهجيات المعتمدة على مصفوفة المسافة لبناء الأشجار على أساس التشابه العام في المورفولوجيا أو سمات أخرى يمكن ملاحظتها (على سبيل المثال في النمط الظاهري، وليس الدنا)، والذي عادة ما يعزى إلى العلاقات الوراثية العرقية.

قبل عام 1990، كانت الاستدلات الوراثية العرقية تمثل كسيناريوهات سردية. وكثيراً ما تكون هذه المنهجيات غامضة وتفتقر إلى معايير صريحة لتقييم الفرضيات البديلة.[4][5][6]

نظرية الخلاصة لإرنست هيكل

في أواخر القرن 19، نظرية التلخيص لإرنست هيكل، أو "القانون الأساسي للنشوء الحيوي"، لاقت قبولاً كبيراً. وعادة ما يعبر عنها "بالوراثة التطورية المُلخصة لنشأة الفرد"، على سبيل المثال تطور عضية مفردة أثناء حياتها، من عـِرس إلى كائن بالغ، الأمر الذي يعكس توالي المراحل البالغة للأنواع التي تنتمي إليها. لكن هذه النظرية رُفضت منذ زمن طويل.[7][8] عوضاً عنها، تطور نشوء الفرد - التاريخ الوراثي العرقي للأنواع لا يمكن قراءته مباشرة من نشأة الفرد، هيث اعتقد هيكل بأن ذلك ممكناً، لكن الصفات من نشأة الفرد يمكن (وتم) استخدامها كبيانات للتحليلات الوراثية العرقية؛ همان النوعين الأكثر ارتباطاً، apomorphies their embryos share.

خط زمني للأحداث الرئيسية

- القرن 14، lex parsimoniae (parsimony principle)، وليام من أوكام، فيلسوف، عالم لاهوت، وراهب فرانسيسكاني إنگليزي، لكن الفكرة في حقيقة الأمر ترجع لأرسطو، المفهوم السابق.

- احتمال بايزي، لتوماس بايز،[9] المفهوم السابق.

- القرن 18، پيير سيمون (ماركيز دى لاپلاس)، قد يكون أول من استخدم (الاحتمال الأرجح)، المفهوم السابق.

- 1809، النظرية التطورية، فلسفة علم الحيوان، لجان-باتيست لامارك، المفهوم السابق، تنبأ به في القرنين 17 و18 كلاً من ڤولتير، ديكارت، ولايبنتز، اقترح لايبنتز أن التغيرات التطورية لحساب الثغرات الملحوظة تقترح بأن العديد من الأنواع أصبحت منقرضة، والأخرى تحولت، والأنواع المختلفة التي تتشارك السمات المشتركة ربما كانت في وقت ما ضمن عرق واحد،[10] كما تنبأ بها بعض الفلاسفة اليونانيين المبكرين مثل أناكسيماندر، في القرن السادس ق.م. وعلماء الذرة في القرن الخامس ق.م، الذين اقترحوا نظريات بدائية للتطور[11]

- 1837، تظهر دفاتر دارون شجرة تطورية[12]

- 1843، التمييز بين التنادد والتماثل (الآن، يشار للأخير بالتقارب)، ريتشارد أوين، المفهوم السابق.

- 1858، عالم الأحياء القديمة هاينريش گيورگ برون (1800-1862) نشر شجرة افتراضية لتصوير "الوصول" الإحاثي للأنواع الجديدة المتشابهة في أعقاب انقراض الأنواع القديمة. لم يقترح برون الآلية المسئولة عن مثل هذه الظاهرة، المفهوم السابق.[13]

- 1858، تنقيح النظرية التطورية، دارون ووالاس،[14] كذلك في أصل الأنواع لدارون في العام التالي، المفهوم السابق.

- 1866، إرنست هيكل، نشر لأول مرة شجرته التطورية المعتمدة على الوراثة العرقية، المفهوم السابق.

- 1893، قانون دولو of Character State Irreversibility,[15] precursor concept

- 1912، الاحتمال الأرجح، الذي أوصى به، حلله، وعممه رونالد فيشر، المفهوم السابق.

- 1921، استخدم تيليارد مصطلح "الوراثة العرقية" وميز بين السمات المهجورة والمتخصصة في نظام تصنيفه[16]

- 1940، مصطلح "فرع حيوي" صاغه لوسيان كينو.

- 1949، Jackknife resampling، موريس كوينويل (تم التنبؤ به عام 1946 من قبل مهالانوبيس واستفاض فيه توكي عام 1958)، المفهوم السابق.

- 1950، جعله ويلي هنيگ مفهوماً رسمياً كلاسيكياً[17]groundplan divergence method لوليام واگنر[18]

- 1953، صياغة "cladogenesis" [19]

- 1960، "cladistic" صاغه كاين وهاريسون[20]

- 1963، أول محاولة لاستخدام الاحتمال الأرجح للوراثة العرقية، إدواردز وكاڤالي-سفورزا[21]

- 1965

- Camin-Sokal parsimony, first parsimony (optimization) criterion and first computer program/algorithm for cladistic analysis both by Camin and Sokal[22]

- character compatibility method, also called clique analysis, introduced independently by Camin and Sokal (loc. cit.) and E. O. Wilson[23]

- 1966

- English translation of Hennig[24]

- "cladistics" and "cladogram" coined (Webster's, loc. cit.)

- 1969

- 1970, Wagner parsimony generalized by Farris[28]

- 1971

- Fitch parsimony, Fitch[29]

- NNI (nearest neighbour interchange), first branch-swapping search strategy, developed independently by Robinson[30] and Moore et al.

- ME (minimum evolution), Kidd and Sgaramella-Zonta[31] (it is unclear if this is the pairwise distance method or related to ML as Edwards and Cavalli-Sforza call ML "minimum evolution".)

- 1972, Adams consensus, Adams[32]

- 1974, first successful application of ML to phylogenetics (for nucleotide sequences), Neyman[33]

- 1976, prefix system for ranks, Farris[34]

- 1977, Dollo parsimony, Farris[35]

- 1979

- 1980, PHYLIP, first software package for phylogenetic analysis, Felsenstein

- 1981

- 1982

- PHYSIS, Mikevich and Farris

- branch and bound, Hendy and Penny[42]

- 1985

- 1986, MacClade, Maddison and Maddison

- 1987, neighbor-joining method Saitou and Nei[46]

- 1988, Hennig86 (version 1.5), Farris

- Bremer support (decay index), Bremer [47]

- 1989

- 1990

- 1991

- 1993, implied weighting Goloboff[54]

- 1994, reduced consensus: RCC (reduced cladistic consensus) for rooted trees, Wilkinson[55]

- 1995, reduced consensus RPC (reduced partition consensus) for unrooted trees, Wilkinson[56]

- 1996, first working methods for BI (Bayesian Inference)independently developed by Li,[57] Mau,[58] and Rannala and Yang[59] and all using MCMC (Markov chain-Monte Carlo)

- 1998, TNT (Tree Analysis Using New Technology), Goloboff, Farris, and Nixon

- 1999, Winclada, Nixon

- 2003, symmetrical resampling, Goloboff[60]

تجمعات الكائنات الحية

انظر أيضا

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group

- Bauplan

- معلوماتية حيوية

- رياضيات حيوية

- علم شجرة الحياة

- Coalescent theory

- شجرة المحتد الحاسوبية

- EDGE of Existence programme

- تصنيف تطوري

- Joe Felsenstein

- عائلة لغوية

- Maximum parsimony

- شجرة المحتد الجرثومية

- الوراثة العرقية الجزيئية

- Noogenesis

- نشأة الفرد

- Ontogeny (psychoanalysis)

- PhyloCode

- Phylodynamics

- Phylogenesis

- Phylogenetic comparative methods

- شبكة وراثية عرقية

- Phylogenetic nomenclature

- الشجرة الوراثة العرقية

- Phylogenetic tree viewers

- برنامج وراثي عرقي

- Phylogenomics

- Phylogeny (psychoanalysis)

- Phylogeography

- Systematics

المصادر

- ^ عبد الجليل هويدي، محمد أحمد هيكل (2004). أساسيات الجيولوجيا التاريخية. مكتبة الدار العربية للكتب.

- ^ "phylogeny". Biology online. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ^ Edwards AWF; Cavalli-Sforza LL (1964). "Reconstruction of evolutionary trees". In Heywood, Vernon Hilton; McNeill, J. (eds.). Phenetic and Phylogenetic Classification. pp. 67–76. OCLC 733025912.

Phylogenetics is the branch of life science concerned with the analysis of molecular sequencing data to study evolutionary relationships among groups of organisms.

- ^ Richard C. Brusca & Gary J. Brusca (2003). Invertebrates (2nd ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-097-5.

- ^ Bock, W.J. (2004). Explanations in systematics. Pp. 49-56. In Williams, D.M. and Forey, P.L. (eds) Milestones in Systematics. London: Systematics Association Special Volume Series 67. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

- ^ Auyang, Sunny Y. (1998). Narratives and Theories in Natural History. In: Foundations of complex-system theories: in economics, evolutionary biology, and statistical physics. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Blechschmidt, Erich (1977) The Beginnings of Human Life. Springer-Verlag Inc., p. 32: "The so-called basic law of biogenetics is wrong. No buts or ifs can mitigate this fact. It is not even a tiny bit correct or correct in a different form, making it valid in a certain percentage. It is totally wrong."

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul; Richard Holm; Dennis Parnell (1963) The Process of Evolution. New York: McGraw–Hill, p. 66: "Its shortcomings have been almost universally pointed out by modern authors, but the idea still has a prominent place in biological mythology. The resemblance of early vertebrate embryos is readily explained without resort to mysterious forces compelling each individual to reclimb its phylogenetic tree."

- ^ Bayes, T. 1763. An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances. Phil. Trans. 53: 370–418.

- ^ Strickberger, Monroe. 1996. Evolution, 2nd. ed. Jones & Bartlett.

- ^ The Theory of Evolution, Teaching Company course, Lecture 1

- ^ Darwin's Tree of Life[dead link]

- ^ J. David Archibald (2009) 'Edward Hitchcock’s Pre-Darwinian (1840) 'Tree of Life'.', Journal of the History of Biology (2009) page 568.

- ^ Darwin, C. R. and A. R. Wallace. 1858. On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection. Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. Zoology 3: 45-50.

- ^ Dollo, Louis. 1893. Les lois de l'évolution. Bull. Soc. Belge Géol. Paléont. Hydrol. 7: 164-66.

- ^ Tillyard R. J. 1921. A new classification of the order Perlaria. Canadian Entomologist 53: 35-43

- ^ Hennig. W. (1950). Grundzuge einer theorie der phylogenetischen systematik. Deutscher Zentralverlag, Berlin.

- ^ Wagner, W.H. Jr. 1952. The fern genus Diellia: structure, affinities, and taxonomy. Univ. Calif. Publ. Botany 26: 1–212.

- ^ Webster's 9th New Collegiate Dictionary

- ^ Cain, A. J., Harrison, G. A. 1960. "Phyletic weighting". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 35: 1–31.

- ^ Edwards, A.W.F, Cavalli-Sforza, L.L. (1963). The reconstruction of evolution. Ann. Hum. Genet. 27: 105–106.

- ^ Camin J.H, Sokal R.R. (1965). A method for deducing branching sequences in phylogeny.Evolution 19: 311–326.

- ^ Wilson, E. O. 1965. A consistency test for phylogenies based on contemporaneous species. Systematic Zoology 14: 214-220.

- ^ Hennig. W. (1966). Phylogenetic systematics. Illinois University Press, Urbana.

- ^ Farris, J.S. 1969. A successive approximations approach to character weighting. Syst. Zool. 18: 374-85.

- ^ أ ب Kluge, A.G, Farris, J.S. (1969). Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. Syst. Zool. 18: 1–32.

- ^ Le Quesne, W. J. 1969. A method of selection of characters in numerical taxonomy. Systematic Zoology 18: 201-205.

- ^ Farris, J.S. (1970). Methods of computing Wagner trees. Syst. Zool. 19: 83–92.

- ^ Fitch, W.M. (1971). Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specified tree topology. Syst. Zool. 20: 406–416.

- ^ Robinson. D.F. 1971. Comparison of labeled trees with valency three. Journal of Combinatorial Theory 11:105–119.

- ^ Kidd, K.K. and Laura Sgaramella-Zonta (1971). Phylogenetic analysis: concepts and methods. Am. J. Human Genet. 23, 235-252.

- ^ Adams, E. (1972). Consensus techniques and the comparison of taxonomic trees. Syst. Zool. 21: 390–397.

- ^ Neyman, J. (1974). Molecular studies: A source of novel statistical problems. In: Gupta SS, Yackel J. (eds), Statistical Decision Theory and Related Topics, pp. 1–27. Academic Press, New York.

- ^ Farris, J.S. (1976). Phylogenetic classification of fossils with recent species. Syst. Zool. 25: 271-282.

- ^ Farris, J.S. (1977). Phylogenetic analysis under Dollo’s Law. Syst. Zool. 26: 77–88.

- ^ Nelson, G.J. 1979. Cladsitic analysis and synthesis: pronciples and definitions with a historical noteon Adanson's Famille des plantes (1763-1764). Syst. Zool. 28: 1-21.

- ^ Gordon, Aé<.D. 1979. A measure of the agreement between rankings. Biometrika 66: 7-15.

- ^ Efron B. (1979). Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 7: 1–26.

- ^ Margush T, McMorris FR. 1981. Consensus n-trees. Bull. Math .Biol. 43, 239–244.

- ^ Sokal, R. R., F. J. Rohlf. 1981. Taxonomic congruence in the Leptopodomorpha re-examined. Syst. Zool. 30:309-325.

- ^ Felsenstein, J. (1981). Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 17: 368–376.

- ^ Hendy MD, Penny D (1982) Branch and bound algorithms to determine minimal evolutionary trees. Math Biosci 59: 277–290.

- ^ Lipscomb, Diana. 1985. The Eukaryotic Kingdoms. Cladistics 1: 127-40.

- ^ Felsenstein J (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791.

- ^ Lanyon, S.M. (1985). Detecting internal inconsistencies in distance data. Syst. Zool. 34: 397-403.

- ^ Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The Neighbor-joining Method: A New Method for Constructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425.

- ^ Bremer, K., 1988. The limits of amino acid sequence data in angiosperm phylogenetic reconstruction. Evolution 42, 795–803

- ^ Farris, J.S. (1989). The retention index and rescaled consistency index. Cladistics 5: 417–419.

- ^ Archie, J.W. 1989. Homoplasy Excess Ratios: new indices for measuring levels of homoplasy in phylogenetic systematics and a critique of the Consistency Index. Syst. Zool. 38: 253-69.

- ^ Bremer. Kåre. 1990. Combinable Component Consensus. Cladistics 6: 369–372.

- ^ D.L. Swofford and G.J. Olsen. 1990. Phylogeny reconstruction. In D.M. Hillis andG. Moritz, editors, Molecular Systematics, pages 411–501. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- ^ Goloboff, P. A. (1991). Homoplasy and the choice among cladograms. Cladistics 7:215–232.

- ^ Goloboff, P. A. (1991b). Random data, homoplasy and information.Cladistics 7:395–406.

- ^ Goloboff, P. A. 1993. Estimating character weights during tree search. Cladistics 9: 83–91.

- ^ Wilkinson, Mark. 1994. Common cladistic information and its consensus representation: reduced Adams and reduced cladistic consensus trees and profiles. Syst. Biol. 43:343-368.

- ^ Wilkinson, Mark. 1995. More on reduced consensus methods. Syst. Biol. 44:436-440.

- ^ Li, S. (1996). Phylogenetic tree construction using Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Ph.D. disseration, Ohio State University, Columbus.

- ^ Mau B (1996) Bayesian phylogenetic inference via Markov chain Monte Carlo Methods. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison (abstract).

- ^ Rannala B, Yang Z. 1996. Probability distribution of molecular evolutionary trees: A new method of phylogenetic inference. J. Mol. Evol. 43: 304–311.

- ^ Goloboff, Pablo; Farris, James; Källersjö, Mari; Oxelman, Bengt; Ramiacuterez, Maria; Szumik, Claudia. 2003. Improvements to resampling measures of group support. Cladistics 19: 324–332.

قراءات للإستزادة

- Schuh, R. T. and A. V. Z. Brower. 2009. Biological Systematics: principles and applications (2nd edn.) ISBN 978-0-8014-4799-0

وصلات خارجية

- The Tree of Life

- Interactive Tree of Life

- PhyloCode

- ExploreTree

- UCMP Exhibit Halls: Phylogeny Wing

- Willi Hennig Society

- Filogenetica.org in Spanish

- PhyloPat, Phylogenetic Patterns

- SplitsTree, program for computing phylogenetic trees and unrooted phylogenetic networks

- Dendroscope, program for drawing phylogenetic trees and rooted phylogenetic networks

- Phylogenetic inferring on the T-REX server

- Mesquite

- NCBI – Systematics and Molecular Phylogenetics

- What Genomes Can Tell Us About the Past – lecture on phylogenetics by Sydney Brenner

- Mikko's Phylogeny Archive

- Who is Who in Phylogenetic Networks research papers related to the phylogenetic network

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction from Gene-Order Data

- ETE: A Python Environment for Tree Exploration This is a programming library to analyze, manipulate and visualize phylogenetic trees. See: Huerta-Cepas, Jaime; Dopazo, Joaquín; Gabaldón, Toni (2010). "ETE: A python Environment for Tree Exploration". BMC Bioinformatics. 11: 24. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-24. PMC 2820433. PMID 20070885.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - PhylomeDB: A public database hosting thousands of gene phylogenies ranging many different species. See: Huerta-Cepas, J.; Capella-Gutierrez, S.; Pryszcz, L. P.; Denisov, I.; Kormes, D.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Gabaldon, T. (2010). "PhylomeDB v3.0: An expanding repository of genome-wide collections of trees, alignments and phylogeny-based orthology and paralogy predictions". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database issue): D556–60. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1109. PMC 3013701. PMID 21075798.

- Lents, N. H.; Cifuentes, O. E.; Carpi, A. (2010). "Teaching the Process of Molecular Phylogeny and Systematics: A Multi-Part Inquiry-Based Exercise". Cell Biology Education. 9 (4): 513. doi:10.1187/cbe.09-10-0076.