التاريخ العسكري لأستراليا

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| تاريخ أستراليا |

|---|

|

| زمنياً |

| قبل التاريخ |

| 1606–1787 |

| 1788–1850 |

| 1851–1900 |

| 1901–1945 |

| Since 1945 |

| خط زمني |

| حسب المواضيع |

| الاستكشاف |

| الدستور • الاتحاد |

| الاقتصادي • السكك الحديدة |

| الهجرة • السكان الأصليون |

| العسكري • الدبلوماسي |

| الولايات والأراضي والمدن |

| نيو ساوث ويلز • سيدني • نيوكاسل |

| ڤيكتوريا • ملبورن |

| كوينزلاند • بريزبين |

| أستراليا الغربية • پرث |

| جنوب أستراليا • أدليد |

| تازمانيا • هوبارت |

| منطقة العاصمة الأسترالية • كانبرا |

| الأرض الشمالية • داروين |

التاريخ العسكري لأستراليا spans the nation's 230-year modern history, from the early Australian frontier wars between Aboriginals and Europeans to the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 21st century. Although this history is short when compared to that of many other nations, Australia has been involved in numerous conflicts and wars, and war and military service have been significant influences on Australian society and national identity, including the Anzac spirit. The relationship between war and Australian society has also been shaped by the enduring themes of Australian strategic culture and its unique security dilemma.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحرب والمجتمع الأسترالي

العصر الاستعماري

القوات البريطانية في أستراليا، 1788–1870

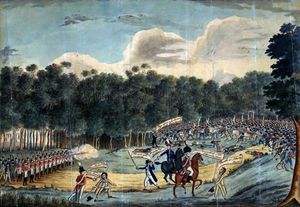

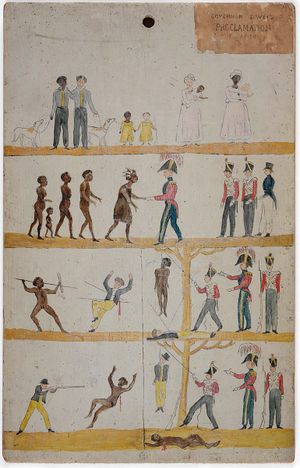

قتال التخوم، 1788–1934

حروب نيوزيلندا، 1861–64

حرب تاراناكي

القوات العسكرية الاستعمارية، 1870–1901

السودان، 1885

During the early years of the 1880s, an Egyptian regime in the Sudan, backed by the British, came under threat from rebellion under the leadership of native Muhammad Ahmad (or Ahmed), known as Mahdi to his followers. In 1883, as part of the Mahdist War, the Egyptians sent an army to deal with the revolt, but they were defeated and faced a difficult campaign of extracting their forces. The British instructed the Egyptians to abandon the Sudan, and sent General Charles Gordon to co-ordinate the evacuation, but he was killed in January 1885. When news of his death arrived in New South Wales in February 1885, the government offered to send forces and meet the contingent's expenses.[3] The New South Wales Contingent consisted of an infantry battalion of 522 men and 24 officers, and an artillery battery of 212 men and sailed from Sydney on 3 March 1885.[4]

The contingent arrived in Suakin on 29 March and were attached to a brigade that consisted of Scots, Grenadier and Coldstream Guards. They subsequently marched for Tamai in a large "square" formation made up of 10,000 men. Reaching the village, they burned huts and returned to Suakin: three Australians were wounded in minor fighting. Most of the contingent was then sent to work on a railway line that was being laid across the desert towards Berber, on the Nile. The Australians were then assigned to guard duties, but soon a camel corps was raised and 50 men volunteered. They rode on a reconnaissance to Takdul on 6 May and were heavily involved in a skirmish during which more than 100 Arabs were killed or captured.[4][5] On 15 May, they made one last sortie to bury the dead from the fighting of the previous March. Meanwhile, the artillery were posted at Handoub and drilled for a month, but they soon rejoined the camp at Suakin.[3]

Eventually the British government decided that the campaign in Sudan was not worth the effort required and left a garrison in Suakin. The New South Wales Contingent sailed for home on 17 May, arriving in Sydney on 19 June 1885.[3] Approximately 770 Australians served in Sudan; nine subsequently died of disease during the return journey while three had been wounded during the campaign.[6]

حرب البوير الثانية، 1899–1902

تمرد الملاكمين، 1900–01

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

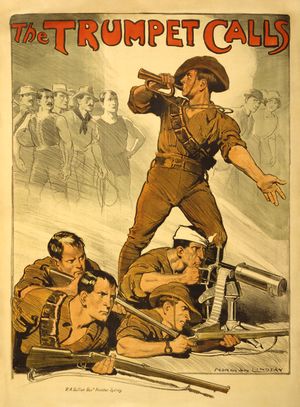

الحرب العالمية الأولى، 1914–18

اندلاع القتال

احتلال غينيا الجديدة الألمانية

گاليپولي

مصر وفلسطين

After the withdrawal from Gallipoli the Australians returned to Egypt and the AIF underwent a major expansion. In 1916 the infantry began to move to France while the cavalry units remained in the Middle East to fight the Turks. Australian troops of the Anzac Mounted Division and the Australian Mounted Division saw action in all the major battles of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, playing a pivotal role in fighting the Turkish troops that were threatening British control of Egypt.[7] The Australian's first saw combat during the Senussi uprising in the Libyan Desert and the Nile Valley, during which the combined British forces successfully put down the primitive pro-Turkish Islamic sect with heavy casualties.[8] The Anzac Mounted Division subsequently saw considerable action in the Battle of Romani against the Turkish between 3–5 August 1916, with the Turks eventually pushed back.[9] Following this victory the British forces went on the offensive in the Sinai, although the pace of the advance was governed by the speed by which the railway and water pipeline could be constructed from the Suez Canal. Rafa was captured on 9 January 1917, while the last of the small Turkish garrisons in the Sinai were eliminated in February.[10]

The advance entered Palestine and an initial, unsuccessful attempt was made to capture Gaza on 26 March 1917, while a second and equally unsuccessful attempt was launched on 19 April. A third assault occurred between 31 October and 7 November and this time both the Anzac Mounted Division and the Australian Mounted Division took part. The battle was a complete success for the British, over-running the Gaza-Beersheba line and capturing 12,000 Turkish soldiers. The critical moment was the capture of Beersheba on the first day, after the Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade charged more than 4 miles (6.4 km). The Turkish trenches were overrun, with the Australians capturing the wells at Beersheeba and securing the valuable water they contained along with over 700 prisoners for the loss of 31 killed and 36 wounded.[11] Later, Australian troops assisted in pushing the Turkish forces out of Palestine and took part in actions at Mughar Ridge, Jerusalem and the Megiddo. The Turkish government surrendered on 30 October 1918.[12] Units of the Light Horse were subsequently used to help put down a nationalist revolt in Egypt in 1919 and did so with efficiency and brutality, although they suffered a number of fatalities in the process.[13]

Meanwhile, the AFC had undergone remarkable development, and its independence as a separate national force was unique among the Dominions. Deploying just a single aircraft to German New Guinea in 1914, the first operational flight did not occur until 27 May 1915 however, when the Mesopotamian Half Flight was called upon to assist in protecting British oil interests in Iraq. The AFC was soon expanded and four squadrons later saw action in Egypt, Palestine and on the Western Front, where they performed well.[14]

ما بين الحربين

الحرب الأهلية الروسية، 1918–19

الحرب الأهلية الاسبانية، 1936–39

الحرب العالمية الثانية، 1939–45

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أوروپا والشرق الأوسط

Australia entered the Second World War on 3 September 1939. At the time of the declaration of war against Germany the Australian military was small and unready for war.[15] Recruiting for a Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) began in mid-September. While there was no rush of volunteers like the First World War, a high proportion of Australian men of military age had enlisted by mid-1940. Four infantry divisions were formed during 1939 and 1940, three of which were dispatched to the Middle East.[16] The RAAF's resources were initially mainly devoted to training airmen for service with the Commonwealth air forces through the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS), through which almost 28,000 Australians were trained during the war.[17]

The Australian military's first major engagements of the war were against Italian forces in the Mediterranean and North Africa. During 1940 the light cruiser إتشإمإيهإس Sydney and five elderly destroyers (dubbed the "Scrap Iron Flotilla" by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels—a title proudly accepted by the ships) took part in a series of operations as part of the British Mediterranean Fleet, and sank several Italian warships.[18] The Army first saw action in January 1941, when the 6th Division formed part of the Commonwealth forces during Operation Compass. The division assaulted and captured Bardia on 5 January and Tobruk on 22 January, with tens of thousands of Italian troops surrendering at both towns.[19] The 6th Division took part in the pursuit of the Italian Army and captured Benghazi on 4 February. In late February it was withdrawn for service in Greece, and was replaced by the 9th Division.[20]

The Australian forces in the Mediterranean endured a number of campaigns during 1941. During April, the 6th Division, other elements of I Corps and several Australian warships formed part of the Allied force which unsuccessfully attempted to defend Greece from German invasion during the Battle of Greece. At the end of this campaign, the 6th Division was evacuated to Egypt and Crete.[21] The force at Crete subsequently fought in the Battle of Crete during May, which also ended in defeat for the Allies. Over 5,000 Australians were captured in these campaigns, and the 6th Division required a long period of rebuilding before it was again ready for combat.[22] The Germans and Italians also went on the offensive in North Africa at the end of March and drove the Commonwealth force there back to near the border with Egypt. The 9th Division and a brigade of the 7th Division were besieged at Tobruk; successfully defending the key port town until they were replaced by British units in October.[23] During June, the main body of the 7th Division, a brigade of the 6th Division and the I Corps headquarters took part in the Syria-Lebanon Campaign against the Vichy French. Resistance was stronger than expected; Australians were involved in most of the fighting and sustained most of the casualties before the French capitulated in early July.[24]

The majority of Australian units in the Mediterranean returned to Australia in early 1942, after the outbreak of the Pacific War. The 9th Division was the largest unit to remain in the Middle East, and played a key role in the First Battle of El Alamein during June and the Second Battle of El Alamein in October.[25] The division returned to Australia in early 1943, but several RAAF squadrons and RAN warships took part in the subsequent Tunisia Campaign and the Italian Campaign from 1943 until the end of the war.[26]

The RAAF's role in the strategic air offensive in Europe formed Australia's main contribution to the defeat of Germany. Approximately 13,000 Australian airmen served in dozens of British and five Australian squadrons in RAF Bomber Command between 1940 and the end of the war.[27] Australians took part in all of Bomber Command's major offensives and suffered heavy losses during raids on German cities and targets in France.[28] Australian aircrew in Bomber Command had one of the highest casualty rates of any part of the Australian military during the Second World War and sustained almost 20 percent of all Australian deaths in combat; 3,486 were killed and hundreds more were taken prisoner.[29] Australian airmen in light bomber and fighter squadrons also participated in the liberation of Western Europe during 1944 and 1945[30] and two RAAF maritime patrol squadrons served in the Battle of the Atlantic.[31]

آسيا والهادي

احتلال اليابان، 1946–52

الحرب الباردة

الحرب الكورية، 1950–53

طوارئ الملايو، 1950–60

النمو العسكري والبحري في الستينيات

المواجهة الإندونيسية-الماليزية، 1962–66

The Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation was fought from 1962 to 1966 between the British Commonwealth and Indonesia over the creation of the Federation of Malaysia, with the Commonwealth attempting to safeguard the security of the new state. The war remained limited, and was fought primarily on the island of Borneo, although a number of Indonesian seaborne and airborne incursions onto the Malay Peninsula did occur.[32] As part of Australia's continuing military commitment to the security of Malaysia, army, naval and airforce units were based there as part of the Far East Strategic Reserve. Regardless the Australian government was wary of involvement in a war with Indonesia and initially limited its involvement to the defence of the Malayan peninsula only. On two occasions Australian troops from 3 RAR were used to help mop up infiltrators from seaborne and airborne incursions at Labis and Pontian, in September and October 1964.[32]

حرب ڤيتنام، 1962–73

عصر ما بعد ڤيتنام

خلق قوة الدفاع الأسترالية، 1976

حرب الخليج، 1991

Australia was a member of the international coalition which contributed military forces to the 1991 Gulf War, deploying a naval task group of two warships, a support ship and a clearance diving team; in total about 750 personnel. The Australian contribution was the first time Australian personnel were deployed to an active war zone since the establishment of the ADF and the deployment tested its capabilities and command structure. However, the Australian force did not see combat, and instead playing a significant role in enforcing the sanctions put in place against Iraq following the invasion of Kuwait. Some ADF personnel serving on exchange with British and American units did see combat, and a few were later decorated for their actions.[33] Following the war, the Navy regularly deployed a frigate to the Persian Gulf or Red Sea to enforce the trade sanctions which continued to be applied to Iraq.[34] A number of Australian airmen and ground crew posted to or on exchange with US and British air forces subsequently participated in enforcing no-fly zones imposed over Iraq between 1991 and 2003.[35]

الألفية الجديدة

تيمور الشرقية، 1999–2013

أفغانستان، 2001–الحاضر

العراق، 2003–11

Australian forces later joined British and American forces during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The initial contribution was also a modest one, consisting of just 2,058 personnel—codenamed Operation Falconer. Major force elements included special forces, rotary and fixed wing aviation and naval units. Army units included elements from the SASR and 4th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (Commando), a CH-47 Chinook detachment and a number of other specialist units. RAN units included the amphibious ship إتشإمإيهإس Kanimbla and the frigates إتشإمإيهإس Darwin and إتشإمإيهإس Anzac, while the RAAF deployed 14 F/A-18 Hornets from No. 75 Squadron, a number of AP-3C Orions and C-130 Hercules.[36] The Australian Special Forces Task Force was one of the first coalition units forces to cross the border into Iraq, while for a few days, the closest ground troops to Baghdad were from the SASR. During the invasion the RAAF also flew its first combat missions since the Vietnam War, with No. 75 Squadron flying a total of 350 sorties and dropping 122 laser-guided bombs.[37]

The Iraqi military quickly proved no match for coalition military power, and with their defeat the bulk of Australian forces were withdrawn. While Australia did not initially take part in the post-war occupation of Iraq, an Australian Army light armoured battlegroup—designated the Al Muthanna Task Group and including 40 ASLAV light armoured vehicles and infantry—was later deployed to Southern Iraq in April 2005 as part of Operation Catalyst. The role of this force was to protect the Japanese engineer contingent in the region and support the training of New Iraqi Army units. The AMTG later became the Overwatch Battle Group (West) (OBG(W)), following the hand back of Al Muthanna province to Iraqi control. Force levels peaked at 1,400 personnel in May 2007 including the OBG(W) in Southern Iraq, the Security Detachment in Baghdad and the Australian Army Training Team—Iraq. A RAN frigate was based in the North Persian Gulf, while RAAF assets included C-130H Hercules and AP-3C elements.[38] Following the election of a new Labor government under Prime Minister Kevin Rudd the bulk of these forces were withdrawn by mid-2009, while RAAF and RAN operations were redirected to other parts of the Middle East Area of Operations as part of Operation Slipper.[39]

Low-level operations continued, however, with a small Australian force of 80 soldiers remaining in Iraq to protect the Australian Embassy in Baghdad as part of SECDET under Operation Kruger.[40] SECDET was finally withdrawn in August 2011, and was replaced by a private military company which took over responsibility for providing security for Australia's diplomatic presence in Iraq.[41] Although more than 17,000 personnel served during operations in Iraq, Australian casualties were relatively light, with two soldiers accidentally killed, while a third Australian died serving with the British Royal Air Force. A further 27 personnel were wounded.[6] Two officers remained in Iraq attached to the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq as part of Operation Riverbank.[42] This operation concluded in November 2013.[43]

التدخل العسكري ضد داعش، 2014–الحاضر

In June 2014 a small number of SASR personnel were deployed to Iraq to protect the Australian embassy when the security of Baghdad was threatened by the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive.[44] Later, in August and September a number of RAAF C-17 and C-130J transport aircraft based in the Middle East were used to conduct airdrops of humanitarian aid to trapped civilians and to airlift arms and munitions to forces in Kurdish-controlled northern Iraq.[45][46][47][48] In late September 2014 an Air Task Group (ATG) and Special Operations Task Group (SOTG) were deployed to Al Minhad Air Base in the United Arab Emirates as part of the coalition to combat Islamic State forces in Iraq.[49] Equipped with F/A-18F Super Hornet strike aircraft, a KC-30A Multi Role Tanker Transport, and an E-7A Wedgetail Airborne Early Warning & Control aircraft, the ATG began operations on 1 October.[50] The SOTG is tasked with operations to advise and assist Iraqi Security Forces,[51] and was deployed to Iraq after a legal framework covering their presence in the country was agreed between the Australian and Iraqi Governments.[52] It began moving into Iraq in early November.[53] In April 2015 a 300-strong unit known as Task Group Taji was deployed to Iraq to train the regular Iraqi Security Forces.[54] In September 2015 airstrikes were extended to Syria.[55] Strike missions concluded in December 2017.[56]

عمليات حفظ السلام والنجدة الإنسانية

إحصائيات عسكرية

| النزاع | التاريخ | عدد المجندين | القتلى | الجرحى | الأسرى | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | 1860–61 | Crew of HMVS Victoria 2,500 in Waikato Regiments |

1 <20 |

Nil Unknown |

Nil | [6] |

| Sudan | 1885 | 770 in NSW Contingent | 9 | 3 | Nil | [6] |

| South Africa | 1899–1902 | 16,463 in Colonial and Commonwealth contingents | 589 | 538 | 100 | [6] |

| China | 1900–01 | 560 in NSW, SA and VIC colonial naval contingents | 6 | Unknown | Nil | [6] |

| First World War | 1914–18 | 416,809 enlisted in AIF (includes AFC) 324,000 AIF members served overseas 9,000 in RAN Total: 425,809 |

61,511 | 155,000 | 4,044 (397 died in captivity) |

[6] |

| Russian Civil War | 1918–19 | 100–150 in NREF and NRRF 48 in Dunsterforce Crew of HMAS Swan |

10 | 40 | Nil | [57] |

| Second World War | 1939–45 | 727,200 in 2nd AIF and Militia 48,900 in RAN 216,900 in RAAF Total: 993,000 |

39,761 | 66,553 | 8,184 (against Germany and Italy) 22,376 (against Japan) (8,031 died in captivity) Total: 30,560 |

[6] |

| Post-war mine clearance (Northern Queensland coast and New Guinea) |

1947–50 | 4 | [58] | |||

| Japan (British Commonwealth Occupation Force) |

1947–1952 | 16,000 | 3 | [58][59] | ||

| Papua New Guinea | 1947–1975 | 13 | [58] | |||

| Middle East (UNTSO) |

1948–present | 1 | [58] | |||

| Berlin Airlift | 1948–1949 | 1 | [58] | |||

| Malayan Emergency | 1948–60 | 7,000 in Army | 39 | 20 | Nil | [6] |

| Kashmir | 1948–1985 | 1 | [58] | |||

| Korean War | 1950–53 | 10,657 in Army 4,507 in RAN 2,000 in RAAF Total: 17,164 |

340 | 1,216 | 29 (1 died in captivity) |

[6] |

| Malta | 1952–1955 | 3 | [58] | |||

| Korea (Post-armistice) |

1953–1957 | 16 | [6] | |||

| South-East Asia (SEATO) |

1955–1975 | 6 | [58] | |||

| Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation | 1962–66 | 3,500 in Army | 16 | 9 | Nil | [6] |

| Malay Peninsula | 1964–1966 | 2 | [58] | |||

| Vietnam War | 1962–73 | 42,700 in Army 2,825 in RAN 4,443 in RAAF Total: 49,968 |

521 | 2,398 | Nil | [6] |

| تايلند | 1965–1968 | 2 | [58] | |||

| Irian Jaya (Operation Cenderawasih) |

1976–1981 | 1 | [58] | |||

| Gulf War | 1991 | 750 | Nil | Nil | Nil | [6] |

| Western Sahara (MINURSO) |

1991–1994 | 1 | [6] | |||

| Somalia | 1992–94 | 1,480 | 1 | Nil | [58] | |

| Bougainville | 1997–2003 | 3,500 | 1 | [58] | ||

| East Timor | 1999–2013 | > 40,000 | 4 | Nil | [6][60][61] | |

| Afghanistan | 2001–present | > 26,000 | 41 | 256 | Nil | [62][63][64] |

| Iraq | 2003–11 | 17,000 | 3 | 27 | Nil | [6] |

| Solomon Islands | 2003–2013 | 7,270 | 1 | [58][65] | ||

| Fiji | 2006 | 2 | [58] | |||

| Total | ~ 102,930 | ~ 226,060 | ~ 34,733 | |||

| Note: In addition, approximately another 3,100 Australians died in various conflicts, serving in either British or other Commonwealth or Allied forces, or the Merchant Navy, or were civilians working with philanthropic organisations, official war correspondents, photographers, or artists.[66] | ||||||

ملاحظات

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ Australian War Memorial 2010, p. 14

- ^ "Governor Arthur's proclamation". National Treasures from Australia's Great Libraries. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت Dennis et al 1995, p. 575.

- ^ أ ب Coulthard-Clark 2001, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Turner 2014, pp. 40–53.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ "Australian War Casualties". Australian War Memorial. 15 December 2005. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Grey 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Bean 1946, p. 188.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Dennis et al 2008, p. 405.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Grey 1999, p. 114.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGrey117 - ^ Dennis et al 2008, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Beaumont 1996a, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Stevens 2006, pp. 60–64, 75.

- ^ Frame 2004, pp. 153–157.

- ^ Long 1973, pp. 54–63.

- ^ Coates 2006, p. 132.

- ^ Grey 2008, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Grey 2008, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Coates 2006, pp. 168–172.

- ^ Odgers 1999, pp. 183–194.

- ^ Stevens 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Odgers 1999, pp. 187–191.

- ^ Stevens 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Long 1973. pp. 379–393

- ^ Odgers 1999, p. 187.

- ^ أ ب Dennis et al 1995, p. 171.

- ^ Kirkland 1991, p. 160.

- ^ Horner 2001, pp. 231–237.

- ^ "Middle East 1991–2003 (US and UK Deployments)". Conflicts. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Dennis et al 2008, p. 248.

- ^ Holmes 2006, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Dennis et al 2008, p. 250.

- ^ "Australia ends Iraq troop presence". Daily Express. 31 July 2009.

- ^ "Global Operations – Department of Defence". Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "Australia withdraws troops guarding Iraq embassy". ABC News. 10 August 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Wiseman, Nick (18 August 2011). "SECDET Hands Over in Iraq". Army News: The Soldiers' Newspaper. Canberra: Department of Defence. p. 3. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ قالب:Cite media release

- ^ Brissenden, Michael (3 July 2014). "Australia scales back embassy staff numbers in Iraq due to safety fears over safety of Baghdad airport". ABC News. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Murphy, Katharine (14 August 2014). "Australian troops complete first humanitarian mission in northern Iraq". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Wroe, David (31 August 2014). "SAS to Protect Crews on Arms Drops in Iraq". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney: Fairfax Media. ISSN 0312-6315.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ قالب:Cite media release

- ^ قالب:Cite media release

- ^ قالب:Cite media release

- ^ "Australian Air Task Group commences operational missions over Iraq". Department of Defence. 2 أكتوبر 2014. Archived from the original on 6 أكتوبر 2014. Retrieved 2 أكتوبر 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Support to Iraq" (PDF). Army: The Soldiers' Newspaper (1338 ed.). Canberra: Department of Defence. 9 October 2014. p. 3. ISSN 0729-5685.

- ^ Brissenden, Michael. "Deadly Australian air strikes dent IS morale in Iraq: Rear Admiral David Johnston". ABC News. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Griffiths, Emma (11 November 2014). "Australian troops 'moving into locations' in Iraq to assist with fight against Islamic State". ABC News. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ قالب:Cite media release

- ^ Coorey, Phillip (9 September 2015). "Australia to take 12,000 refugees, boost aid and bomb Syria". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Australian Operation Okra Air Combat Mission to end". Australian Aviation. 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMuirden78 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض "Deaths as a result of service with Australian units". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 19 July 2015.

- ^ "British Commonwealth Occupation Force 1945–52". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAWMPeacekeeping - ^ Copeland, Paul (2010). "The Inquiry into Recognition for Defence Force Personnel Who served as Peacekeepers from 1947 Onward" (PDF). Australian Peacekeeper & Peacemaker Veterans' Association Incorporated, National Executive. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOPSlipper - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةONeill - ^ Emma, Griffiths (17 December 2013). "Australian soldiers complete withdrawal from Afghanistan's Uruzgan province". ABC News. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Australia-led Combined Task Forces Concludes Role With RAMSI". Department of Defence (Press release). 2 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "About the Commemorative Roll". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

مراجع

- Australian War Memorial (2010). Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009–2010 (PDF). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISSN 1441-4198.

- Australian Army (2008). The Fundamentals of Land Warfare (PDF). Canberra: Australian Army. OCLC 223250226. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2008.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Bean, Charles (1921). The Story of Anzac: From the Outbreak of War to the End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign May 4, 1915. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. Volume One (1st ed.). Sydney: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 251999955.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Bean, Charles (1946). Anzac to Amiens. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220477286.

- Beaumont, Joan (1995). "Australia's War". In Beaumont, Joan (ed.). Australia's War, 1914–1918. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. pp. 1–34. ISBN 1863734619.

- Beaumont, Joan (1996a). "Australia's War: Europe and the Middle East". In Beaumont, Joan (ed.). Australia's War, 1939–1945. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. pp. 1–25. ISBN 1-86448-039-4.

- Beaumont, Joan (1996b). "Australia's War: Asia and the Pacific". In Beaumont, Joan (ed.). Australia's War, 1939–1945. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. pp. 26–53. ISBN 1-86448-039-4.

- Bullard, Steven (2017). In Their Time of Need: Australia's Overseas Emergency Relief Operations, 1918–2006. The Official History of Australian Peacekeeping, Humanitarian and Post-Cold War Operations. Vol. Volume VI. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107026346.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Breen, Bob (1992). The Battle of Kapyong: 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, Korea 23–24 April 1951. Georges Heights, New South Wales: Headquarters Training Command. ISBN 0-642-18222-1.

- Cassells, Vic (2000). The Capital Ships: Their Battles and Their Badges. East Roseville, New South Wales: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7318-0941-6. OCLC 48761594.

- Coates, John (2006). An Atlas of Australia's Wars. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555914-2.

- Connery, David; Cran, David; Evered, David (2012). Conducting Counterinsurgency – Reconstruction Task Force 4 in Afghanistan. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 9781921941771.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (First ed.). St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2. OCLC 39097011.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (Second ed.). Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-634-7. OCLC 48793439.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey (1996). Emergency and Confrontation: Australian Military Operations in Malaya and Borneo 1950–1966. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-302-7. OCLC 187450156.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin; Bou, Jean (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Eather, Steve (1996). Odd Jobs: RAAF Operations in Japan, the Berlin Airlift, Korea, Malaya & Malta, 1946–1960. RAAF Williams, Victoria: RAAF Museum. ISBN 0-642-23482-5.

- Evans, Mark, ed. (2005). The Tyranny of Dissonance: Australia's Strategic Culture and Way of War 1901–2005. Study Paper No. 306. Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-29607-3.

- Frame, Tom (2004). No Pleasure Cruise. The Story of the Royal Australian Navy. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-233-4.

- Grey, Jeffrey (1999). A Military History of Australia (Second ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64483-6.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (Third ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

- Ham, Paul (2007). Vietnam: The Australian War. Sydney: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-7322-8237-0.

- Holmes, Tony (2006). "RAAF Hornets at War". Australian Aviation. Manly: Aerospace Publications (224): 38–39. ISSN 0813-0876.

- Horner, David (1989). SAS: Phantoms of the Jungle: A History of the Australian Special Air Service. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-520006-8. OCLC 23828245.

- Horner, David (May 1993). "Defending Australia in 1942". The Pacific War 1942. War and Society. Canberra: Department of History, Australian Defence Force Academy. pp. 1–21. ISSN 0729-2473.

- Horner, David (2001). Making the Australian Defence Force. The Australian Centenary History of Defence. Vol. Volume IV. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554117-0.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Horner, David; Bou, Jean, eds. (2008). Duty First: A History of the Royal Australian Regiment (2nd ed.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-374-5.

- Kirkland, Frederick (1991). Operation Damask: The Gulf War Iraq – Kuwait 1990–1991. Cremorne: Plaza Historical Service. ISBN 0-9587491-1-6. OCLC 27614090.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Red Coats to Cams. A History of Australian Infantry 1788 to 2001. Sydney: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 1-876439-99-8.

- Londey, Peter (2004). Other People's Wars: A History of Australian Peacekeeping. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-651-7. OCLC 57212671.

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. Volume 7. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 1297619.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Long, Gavin (1973). The Six Years War: A Concise History of Australia in the 1939–1945 War. Canberra: The Australian War Memorial and the Australian Government Printing Service. ISBN 0-642-99375-0.

- Macintyre, Stuart (1999). A Concise History of Australia. Cambridge Consise Histories (First ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62577-7.

- McIntyre, William David (1995). Background to the Anzus Pact: Policy-making, Strategy and Diplomacy, 1945–55. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-12439-2.

- Macdougall, Anthony (2001) [1991]. Australians at War: A Pictorial History. Noble Park: Five Mile Press. ISBN 1-86503-865-2.

- McNeill, Ian; Ekins, Ashley (2003). On the Offensive: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1967–1968. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. Volume Eight. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-304-3.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Millar, Thomas (1978). Australia in Peace and War: Foreign Relations 1788–1977. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 0-7081-1575-6.

- Murphy, John (1993). Harvest of Fear: Australia's Vietnam War. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-449-X. OCLC 260164058.

- Nicholls, Bob (1986). Bluejackets & Boxers: Australia's Naval Expedition to the Boxer Uprising. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-86861-799-7.

- Odgers, George (1994). Diggers: The Australian Army, Navy and Air Force in Eleven Wars. Vol. Volume 1. London: Lansdowne. ISBN 978-1-86302-385-6. OCLC 31743147.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Odgers, George (1999). 100 Years of Australians at War. Sydney: Lansdowne. ISBN 1-86302-669-X.

- Odgers, George (2000). Remembering Korea: Australians in the War of 1950–53. Sydney: Landsdowne Publishing. ISBN 1-86302-679-7. OCLC 50315481.

- Reeve, John; Stevens, David (2001). Southern Trident: Strategy, History, and the Rise of Australian Naval Power. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-462-X. OCLC 47367004.

- Reeve, John; Stevens, David (2003). The Face of Naval Battle: The Human Experience of Modern War at Sea. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-667-3. OCLC 52647129.

- Stephens, Alan (2001). The Royal Australian Air Force. The Australian Centenary History of Defence. Vol. Volume II. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554115-4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Stevens, David (2001). The Royal Australian Navy. The Australian Centenary History of Defence. Vol. Volume III. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554116-2.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Tewes, Alex; Rayner, Laura; Kavanaugh, Kelly (2004). Australia's Maritime Strategy in the 21st Century. Australian Parliamentary Library Research Brief. Vol. 4 2004–05. Canberra: Australian Parliament House. OCLC 224183782. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Thomson, Mark (2005). Punching Above Our Weight? Australia as a Middle Power. Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute. OCLC 224546956.

- Turner, Trevor (2014). "The Camel Corps: New South Wales Sudan contingent, 1885". Sabretache. Garran, Australian Capital Territory: Military Historical Society of Australia. LV (4, December): 40–53. ISSN 0048-8933.

- Walhert, Glenn (2008). Exploring Gallipoli: An Australian Army Battlefield Guide. Canberra: Army History Unit. ISBN 978-0-9804753-5-7.

- White, Hugh (2002). "Australian Defence Policy and the Possibility of War". Australian Journal of International Affairs. Canberra: The Institute. 56 (2): 253–264. doi:10.1080/10357710220147451. ISSN 1465-332X.

للاستزادة

- Dean, Peter J. (2018). McArthur's Coalition: US and Australian operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1942–1945. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700626045.