بفلو، نيويورك

بفلو، نيويورك | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| مدينة بفلو | |||

تجاه عقارب الساعة من أعلى: وسط مدينة بفلو، أفق بفلو عند الغسق، جسر السلام، بنك توفير بفلو، قاعة المقاطعة والمدينة، ميدان نياگرا، وقاعة مدينة بفلو. | |||

| أصل الاسم: Named after the nearby Buffalo Creek, which was named by French and Moravian explorers[1][2][3] | |||

| الكنية: Queen City, City of Good Neighbors, City of No Illusions, Nickel City, Queen City of the Lakes, City of Light, City of Trees[4] | |||

خرائط تفاعلية لبفلو | |||

| الإحداثيات: 42°54′17″N 78°50′58″W / 42.90472°N 78.84944°W | |||

| البلد | الولايات المتحدة | ||

| الولاية | نيويورك | ||

| المقاطعة | مقاطعة إيري | ||

| أول استيطان (كقرية) | 1789 | ||

| تأسست | 1801 | ||

| دُمجت (كمدينة) | 1832 | ||

| الحكومة | |||

| • العمدة | بيرون براون (د) | ||

| • المجلس العمومي | مجلس المدينة | ||

| المساحة | |||

| • مدينة | 52٫5 ميل² (136٫0 كم²) | ||

| • البر | 40٫6 ميل² (105٫2 كم²) | ||

| • الماء | 11٫9 ميل² (30٫8 كم²) | ||

| المنسوب | 600 ft (183 m) | ||

| التعداد (2013) | |||

| • مدينة | 258٬959 (US: 73) | ||

| • الكثافة | 6٬436٫2/sq mi (2٬568٫8/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 935٬906 (US: 46) | ||

| • العمرانية | 1٬134٬210 (US: 49) | ||

| • CSA | 1٬213٬668 (US: 44) | ||

| صفة المواطن | بفلونيون | ||

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−5 (EST) | ||

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||

| الرمز البريدي | 14200 | ||

| مفتاح الهاتف | 716 | ||

| FIPS code | 36-11000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 0973345 | ||

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.city-buffalo.com | ||

| [5][6] | |||

بفلو ( Buffalo ؛ /ˈbʌfəloʊ/)، هي مدينة بولاية نيويورك الأمريكية ومقعد مقاطعة إيري.[7] تقع في غرب نيويورك على الشواطئ الشرقية لبحيرة إيري وعند رأس نهر نياگرا عن عبوره من فورت إيري، اونتاريو، كندا، وتعتبر بفلو هي المدينة الرئيسية في منطقة بفلو-نياگرا فولز الحضرية، أكبر في Upstate New York وفي الترتيب 46 في الولايات المتحدة.[8] في تعداد 2010، كان عدد سكان المدينة 261.310 نسمة، مما يجعلها في الترتيب 69 من حيث عدد السكان بالولايات المتحدة، والثانية في الولاية بعد مدينة نيويورك.[9] يبلغ تعداد سكان منطقة بفلو-نياگرا-كاتاراوگس الاحصائية المجمعة 1,215,826 نسمة.[10]

تأسست حوالي عام 1789 كتجمع تجاري صغير بالقرب من جدول بفلو،[5] سرعان ما نمت بفلو بعد فتح قناة إيري عام 1825، مع المدينة التي كانت تمثل الطرف الغربي لها. بحلول 1900، كانت بفلو ثامن أكبر مدينة في الولايات المتحدة،[11] وأصبحت محور سكك حديدية رئيسية،[12] وأكبر مركز لطحن الحبوب في البلاد.[13] شهدت المدينة تحولاً كبيراً في الجزء الأخير من القرن 20: تغير مسار الشحن من البحيرات العظمى بافتتاح ممر سانت لويس البحري، وانتقلت صناعة الصلب والصناعات الثقيلة الأخرى إلى أمكان مثل الصين.[14] مع بدء أمتراك في السبعينيات، تُركت أيضاً محطة بفلو المركزية، وأعيد تسيير القطارات إلى محطة أخرى بالقرب من ديپو، نيويورك ومحطة شارع البورصة. بحلول 1990، تراجع عدد السكان في مقاطعة إيري إلى أقل مما كان عليه عام 1960.[15]

اليوم، أكبر القطاعات الاقتصادية بالمنطقة هي الخدمات المالية، التكنولوجيا،[16] الرعاية الصحية والتعليم،[17] وقد استمرت هذه القطاعات في النمو بالرغم من تخلف الاقتصاد الوطني والعالمي.[18]

التاريخ

Pre-Columbian era to European exploration

Before the arrival of Europeans, nomadic Paleo-Indians inhabited the western New York region from the 8th millennium BCE. The Woodland period began around 1000 BC, marked by the rise of the Iroquois Confederacy and the spread of its tribes throughout the state.[19][20] Seventeenth-century Jesuit missionaries were the first Europeans to visit the area.[21]

During French exploration of the region in 1620, the region was sparsely populated and occupied by the agrarian Erie people in the south and the Wenrohronon (Wenro) of the Neutral Nation in the north.[19] The Neutral grew tobacco and hemp to trade with the Iroquois, who traded furs with the French for European goods.[19] The tribes used animal- and war paths to travel and move goods across what today is New York State. (Centuries later, these same paths were gradually improved, then paved, then developed into major modern roads.)[19] During the Beaver Wars in the mid-17th century the Senecas partly wiped out and partly absorbed the Erie and Neutrals in the region.[22][23][24] Native Americans did not settle along Buffalo Creek permanently until 1780, when displaced Senecas were relocated from Fort Niagara.[21]

Louis Hennepin and Sieur de La Salle explored the upper Niagara and Ontario regions in the late 1670s.[25] In 1679, La Salle's ship, Le Griffon, became the first to sail above Niagara Falls near Cayuga Creek.[26] Baron de Lahontan visited the site of Buffalo in 1687.[27] A small French settlement along Buffalo Creek lasted for only a year (1758). After the French and Indian War, the region was ruled by Britain.[21] After the American Revolution, the Province of New York—now a U.S. state—began westward expansion, looking for arable land by following the Iroquois.[28]

New York and Massachusetts were vying for the territory which included Buffalo, and Massachusetts had the right to purchase all but a one-mile-(1600-meter)-wide portion of land. The rights to the Massachusetts territories were sold to Robert Morris in 1791.[29] Despite objections from Seneca chief Red Jacket, Morris brokered a deal between fellow chief Cornplanter and the Dutch dummy corporation Holland Land Company.[أ][30][31] The Holland Land Purchase gave the Senecas three reservations, and the Holland Land Company received 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) for about thirty-three cents per acre.[30]

Permanent white settlers along the creek were prisoners captured during the Revolutionary War.[32][21] Early landowners were Iroquois interpreter Captain William Johnston, former enslaved man Joseph "Black Joe" Hodges and Cornelius Winney, a Dutch trader who arrived in 1789.[21][33] As a result of the war, in which the Iroquois sided with the British Army, Iroquois territory was gradually reduced in the late 1700s by European settlers through successive statewide treaties which included the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784) and the First Treaty of Buffalo Creek (1788).[34] The Iroquois were moved onto reservations, including Buffalo Creek. By the end of the 18th century, only 338 sq mi (216,000 acres; 880 km2; 88,000 ha) of reservations remained.[35]

After the Treaty of Big Tree removed Iroquois title to lands west of the Genesee River in 1797, Joseph Ellicott surveyed land at the mouth of Buffalo Creek.[32][36] In the middle of the village was an intersection of eight streets at present-day Niagara Square. Originally named New Amsterdam, its name was soon changed to Buffalo.[37]

Erie Canal, grain and commerce

The village of Buffalo was named for Buffalo Creek.[ب][39] British military engineer John Montresor referred to "Buffalo Creek" in his 1764 journal, the earliest recorded appearance of the name.[40] A road to Pennsylvania from Buffalo was built in 1802 for migrants traveling to the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio.[41] Before an east–west turnpike across the state was completed, traveling from Albany to Buffalo would take a week; a trip from nearby Williamsville to Batavia could take over three days.[42][ت]

British forces burned Buffalo and the northwestern village of Black Rock in 1813.[43] The battle and subsequent fire was in response to the destruction of Niagara-on-the-Lake by American forces and other skirmishes during the War of 1812.[44][45][21] Rebuilding was swift, completed in 1815.[46][45] As a remote outpost, village residents hoped that the proposed Erie Canal would bring prosperity to the area.[30] To accomplish this, Buffalo's harbor was expanded with the help of Samuel Wilkeson; it was selected as the canal's terminus over the rival Black Rock.[21] It opened in 1825, ushering in commerce, manufacturing and hydropower.[30] By the following year, the 130 sq mi (340 km2) Buffalo Creek Reservation (at the western border of the village) was transferred to Buffalo.[35] Buffalo was incorporated as a city in 1832.[47] During the 1830s, businessman Benjamin Rathbun significantly expanded its business district.[30] The city doubled in size from 1845 to 1855. Almost two-thirds of the city's population was foreign-born, largely a mix of unskilled (or educated) Irish and German Catholics.[48][49]

Fugitive slaves made their way north to Buffalo during the 1840s.[50] Buffalo was a terminus of the Underground Railroad, with many free blacks crossing the Niagara River to Fort Erie, Ontario;[51] others remained in Buffalo.[48] During this time, Buffalo's port continued to develop. Passenger and commercial traffic expanded, leading to the creation of feeder canals and the expansion of the city's harbor.[52] Unloading grain in Buffalo was a laborious job, and grain handlers working on lake freighters would make $1.50 a day (equivalent to $37 in 2022[53]) in a six-day work week.[52] Local inventor Joseph Dart and engineer Robert Dunbar created the grain elevator in 1843, adapting the steam-powered elevator. Dart's Elevator initially processed one thousand bushels per hour, speeding global distribution to consumers.[52] Buffalo was the transshipment hub of the Great Lakes, and weather, maritime and political events in other Great Lakes cities had a direct impact on the city's economy.[52] In addition to grain, Buffalo's primary imports included agricultural products from the Midwest (meat, whiskey, lumber and tobacco), and its exports included leather, ships and iron products. The mid-19th century saw the rise of new manufacturing capabilities, particularly with iron.[52]

By the 1860s, many railroads terminated in Buffalo; they included the Buffalo, Bradford and Pittsburgh Railroad, Buffalo and Erie Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, and the Lehigh Valley Railroad.[27] During this time, Buffalo controlled one-quarter of all shipping traffic on Lake Erie.[27] After the Civil War, canal traffic began to drop as railroads expanded into Buffalo.[54] Unionization began to take hold in the late 19th century, highlighted by the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and 1892 Buffalo switchmen's strike.[55]

Steel, challenges, and the modern era

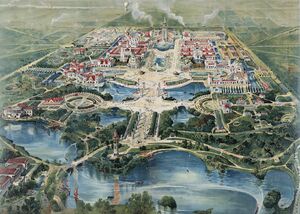

At the start of the 20th century, Buffalo was the world's leading grain port and a national flour-milling hub.[56] Local mills were among the first to benefit from hydroelectricity generated by the Niagara River. Buffalo hosted the 1901 Pan-American Exposition after the Spanish–American War, showcasing the nation's advances in art, architecture, and electricity. Its centerpiece was the Electric Tower, with over two million light bulbs, but some exhibits were jingoistic and racially charged.[57][58][59] At the exposition, President William McKinley was assassinated by anarchist Leon Czolgosz.[60] When McKinley died, Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in at the Wilcox Mansion in Buffalo.[61]

Attorney John Milburn and local industrialists and convinced the Lackawanna Iron and Steel Company to relocate from Scranton, Pennsylvania to the town of West Seneca in 1904. Employment was competitive, with many Eastern Europeans and Scrantonians vying for jobs.[54] From the late 19th century to the 1920s, mergers and acquisitions led to distant ownership of local companies; this had a negative effect on the city's economy.[62][63] Examples include the acquisition of Lackawanna Steel by Bethlehem Steel and, later, the relocation of Curtiss-Wright in the 1940s.[64] The Great Depression saw severe unemployment, especially among the working class. New Deal relief programs operated in full force, and the city became a stronghold of labor unions and the Democratic Party.[65]

During World War II, Buffalo regained its manufacturing strength as military contracts enabled the city to manufacture steel, chemicals, aircraft, trucks and ammunition.[64] The 15th-most-populous US city in 1950, Buffalo's economy relied almost entirely on manufacturing; eighty percent of area jobs were in the sector.[64] The city also had over a dozen railway terminals, as railroads remained a significant industry.[63]

The St. Lawrence Seaway was proposed in the 19th century as a faster shipping route to Europe, and later as part of a bi-national hydroelectric project with Canada.[64] Its combination with an expanded Welland Canal led to a grim outlook for Buffalo's economy. After its 1959 opening, the city's port and barge canal became largely irrelevant. Shipbuilding in Buffalo wound down in the 1960s due to reduced waterfront activity, ending an industry which had been part of the city's economy since 1812.[66] Downsizing of the steel mills was attributed to the threat of higher wages and unionization efforts.[64] Racial tensions culminated in riots in 1967.[64] Suburbanization led to the selection of the town of Amherst for the new University at Buffalo campus by 1970.[64] Unwilling to modernize its plant, Bethlehem Steel began cutting thousands of jobs in Lackawanna during the mid-1970s before closing it in 1983.[62] The region lost at least 70,000 jobs between 1970 and 1984.[62] Like much of the Rust Belt, Buffalo has focused on recovering from the effects of late-20th-century deindustrialization.[67]

الجغرافيا

الطبوغرافيا

Buffalo is on the eastern end of Lake Erie opposite Fort Erie, Ontario. It is at the head of the Niagara River, which flows north over Niagara Falls into Lake Ontario.

The Buffalo metropolitan area is on the Erie/Ontario Lake Plain of the Eastern Great Lakes Lowlands, a narrow plain extending east to Utica, New York.[68][69] The city is generally flat, except for elevation changes in the University Heights and Fruit Belt neighborhoods.[70] The Southtowns are hillier, leading to the Cattaraugus Hills in the Appalachian Upland.[68][69] Several types of shale, limestone and lagerstätten are prevalent in Buffalo and its surrounding area, lining their stream beds.[71]

According to Fox Weather, Buffalo is one of the top five snowiest large cities in the country, receiving, on average, 95 inches of snow annually.

Although the city has not experienced any recent or significant earthquakes, Buffalo is in the Southern Great Lakes Seismic Zone (part of the Great Lakes tectonic zone).[72][73] Buffalo has four channels within its boundaries: the Niagara River, Buffalo River (and Creek), Scajaquada Creek, and the Black Rock Canal, adjacent to the Niagara River.[74] The city's Bureau of Forestry maintains a database of over seventy thousand trees.[75]

According to the United States Census Bureau, Buffalo has an area of 52.5 sq mi (136 km2); 40.38 sq mi (104.6 km2) is land, and the rest is water.[76] The city's total area is 22.66 percent water. In 2010, its population density was 6,470.6 per square mile.[76]

أفق المدينة

Buffalo's architecture is diverse, with a collection of 19th- and 20th-century buildings.[77] Downtown Buffalo landmarks include Louis Sullivan's Guaranty Building, an early skyscraper;[78][79] the Ellicott Square Building, once one of the largest of its kind in the world;[80] the Art Deco Buffalo City Hall and the McKinley Monument, and the Electric Tower. Beyond downtown, the Buffalo Central Terminal was built in the Broadway-Fillmore neighborhood in 1929; the Richardson Olmsted Complex, built in 1881, was an insane asylum[81] until its closure in the 1970s.[82] Urban renewal from the 1950s to the 1970s spawned the Brutalist-style Buffalo City Court Building and Seneca One Tower, the city's tallest building.[83] In the city's Parkside neighborhood, the Darwin D. Martin House was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in his Prairie School style.[84] Since 2016, Washington DC real estate developer Douglas Jemal has been acquiring, and redeveloping iconic properties throughout the city.[85]

الأحياء

According to Mark Goldman, the city has a "tradition of separate and independent settlements".[86] The boundaries of Buffalo's neighborhoods have changed over time. The city is divided into five districts, each containing several neighborhoods, for a total of thirty-five neighborhoods.[87] Main Street divides Buffalo's east and west sides, and the west side was fully developed earlier.[86] This division is seen in architectural styles, street names, neighborhood and district boundaries, demographics, and socioeconomic conditions; Buffalo's West Side is generally more affluent than its East Side.[88][89]

Several neighborhoods in Buffalo have had increased investment since the 1990s, beginning with the Elmwood Village.[90] The 2002 redevelopment of the Larkin Terminal Warehouse led to the creation of Larkinville, home to several mixed-use projects and anchored by corporate offices.[91] Downtown Buffalo and its central business district (CBD) had a 10.6-percent increase in residents from 2010 to 2017, as over 1,061 housing units became available;[92] the Seneca One Tower was redeveloped in 2020.[93] Other revitalized areas include Chandler Street, in the Grant-Amherst neighborhood, and Hertel Avenue in Parkside.[90][94]

The Buffalo Common Council adopted its Green Code in 2017, replacing zoning regulations which were over sixty years old. Its emphasis on regulations promoting pedestrian safety and mixed land use received an award at the 2019 Congress for the New Urbanism conference.[95]

المناخ

Buffalo has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb/Dfa),[96][97] and temperatures have been warming with the rest of the US.[98] Lake-effect snow is characteristic of Buffalo winters, with snow bands (producing intense snowfall in the city and surrounding area) depending on wind direction off Lake Erie.[99] However, Buffalo is rarely the snowiest city in the state.[100][101] The Blizzard of 1977 resulted from a combination of high winds and snow which accumulated on land and on the frozen Lake Erie.[102] Although snow does not typically impair the city's operation, it can cause significant damage in autumn (as the October 2006 storm did).[103] In November 2014 (called "Snowvember"), the region had a record-breaking storm which produced over 5+1⁄2 ft (66 in; 170 cm) of snow.[104] Buffalo's lowest recorded temperature was −20 °F (−29 °C), which occurred twice: on February 9, 1934, and February 2, 1961.[105]

Although the city's summers are drier and sunnier than other cities in the northeastern United States, its vegetation receives enough precipitation to remain hydrated.[97] Buffalo summers are characterized by abundant sunshine, with moderate humidity and temperatures;[97] the city benefits from cool, southwestern Lake Erie summer breezes which temper warmer temperatures.[97][69] Temperatures rise above 90 °F (32.2 °C) an average of three times a year.[97] No official recording of 100 °F (37.8 °C) or more has occurred to date, with a maximum temperature of 99 °F (37 °C) reached on August 27, 1948.[105] Rainfall is moderate, typically falling at night, and cooler lake temperatures hinder storm development in July.[97][106] August is usually rainier and muggier, as the warmer lake loses its temperature-controlling ability.[97]

قالب:Buffalo, New York weatherbox

الديموغرافيا

| التعداد التاريخي | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| التعداد | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 1٬508 | — | |

| 1820 | 2٬095 | 38٫9% | |

| 1830 | 8٬668 | 313٫7% | |

| 1840 | 18٬213 | 110٫1% | |

| 1850 | 42٬261 | 132�0% | |

| 1860 | 81٬129 | 92�0% | |

| 1870 | 117٬714 | 45٫1% | |

| 1880 | 155٬134 | 31٫8% | |

| 1890 | 255٬664 | 64٫8% | |

| 1900 | 352٬387 | 37٫8% | |

| 1910 | 423٬715 | 20٫2% | |

| 1920 | 506٬775 | 19٫6% | |

| 1930 | 573٬076 | 13٫1% | |

| 1940 | 575٬901 | 0٫5% | |

| 1950 | 580٬132 | 0٫7% | |

| 1960 | 532٬759 | −8٫2% | |

| 1970 | 462٬768 | −13٫1% | |

| 1980 | 357٬870 | −22٫7% | |

| 1990 | 328٬123 | −8٫3% | |

| 2000 | 292٬648 | −10٫8% | |

| 2010 | 261٬310 | −10٫7% | |

| 2020 | 278٬349 | 6٫5% | |

| 2022 (تق.) | 276٬486 | −0٫7% | |

| Historical Population Figures[107] U.S. Decennial Census[108] | |||

| أخفالتركيبة العرقية | 2023[109] | 2020[76] | 2010[110] | 1990[111] | 1970[111] | 1940[111] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 47.8% | 41.9% | 50.4% | 64.7% | 78.7% | 96.8% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 44.7% | 39.0% | 45.8% | 63.1% | n/a | n/a |

| African Americans | 33.3% | 36.9% | 38.6% | 30.7% | 20.4% | 3.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 12.2% | 12.8% | 10.5% | 4.9% | 1.6%[ث] | n/a |

| Asian Americans | 6.7% | 7.6% | 3.2% | 1.0% | 0.2% | n/a |

| Other race | 6.3% | 5.3% | 3.1% | 2.8% | 0.2% | n/a |

Several hundred Seneca, Tuscarora and other Iroquois tribal peoples were the primary residents of the Buffalo area before 1800, concentrated along Buffalo Creek.[112] After the Revolutionary War, settlers from New England and eastern New York began to move into the area.

From the 1830s to the 1850s, they were joined by Irish and German immigrants from Europe, both peasants and working class, who settled in enclaves on the city's south and east sides.[48] At the turn of the 20th century, Polish immigrants replaced Germans on the East Side, who moved to newer housing; Italian immigrant families settled throughout the city, primarily on the lower West Side.[86]

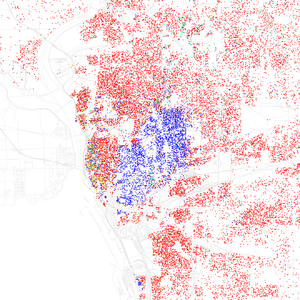

During the 1830s, Buffalo residents were generally intolerant of the small groups of Black Americans who began settling on the city's East Side.[48][ج] In the 20th century, wartime and manufacturing jobs attracted Black Americans from the South during the First and Second Great Migrations. In the World War II and postwar years from 1940 to 1970, the city's Black population rose by 433 percent. They replaced most of the Polish community on the East Side, who were moving out to suburbs.[113][114] However, the effects of redlining, steering,[115] social inequality, blockbusting, white flight[115] and other racial policies resulted in the city (and region) becoming one of the most segregated in the U.S.[114][116][117]

During the 1940s and 1950s, Puerto Rican migrants arrived en masse, also seeking industrial jobs, settling on the East Side and moving westward.[118] In the 21st century, Buffalo is classified as a majority minority city, with a plurality of residents who are Black and Latino.

Buffalo has experienced effects of urban decay since the 1970s, and also saw population loss to the suburbs and Sun Belt states, and experienced job losses from deindustrialization.[119] The city's population peaked at 580,132 in 1950, when Buffalo was the 15th-largest city in the United States – down from the eighth-largest city in 1900, after its growth rate slowed during the 1920s.[56] Buffalo's population began declining in the second half of the 20th century, due to suburbanization and loss of industrial jobs, and the city's population is now less than half its peak population in 1950. Buffalo finally saw a population gain of 6.5% in the 2020 census, reversing a decades long trend of population decline. The city has 278,349 residents as of the 2020 census, making it the 76th-largest city in the United States.[120] Its metropolitan area had 1.1 million residents in 2020, the country's 49th-largest.[121]

Compared to other major US metropolitan areas, the number of foreign-born immigrants to Buffalo is low. New immigrants are primarily resettled refugees (especially from war- or disaster-affected nations) and refugees who had previously settled in other U.S. cities.[122] During the early 2000s, most immigrants came from Canada and Yemen; this shifted in the 2010s to Burmese (Karen) refugees and Bangladeshi immigrants.[122] Between 2008 and 2016, Burmese, Somali, Bhutanese, and Iraqi Americans were the four largest ethnic immigrant groups in Erie County.[122]

Poverty has remained an issue for the city; in 2019, it was estimated that 30.1 percent of individuals and 24.8 percent of families lived below the federal poverty line.[76] Per capita income was $24,400 and household income was $37,354: much less than the national average.[123][76] A 2008 report noted that although food deserts were seen in larger cities and not in Buffalo, the city's neighborhoods of color have access only to smaller grocery stores and lack the supermarkets more typical of newer, white neighborhoods.[124] A 2018 report noted that over fifty city blocks on Buffalo's East Side lacked adequate access to a supermarket.[114]

Health disparities exist compared to the rest of the state: Erie County's average 2019 lifespan was three years lower (78.4 years); its 17-percent smoking and 30-percent obesity rates were slightly higher than the state average.[125] According to the Partnership for the Public Good, educational achievement in the city is lower than in the surrounding area; city residents are almost twice as likely as adults in the metropolitan area to lack a high-school diploma.[126]

Religion

During the early 19th century, Presbyterian missionaries tried to convert the Seneca people on the Buffalo Creek Reservation to Christianity. Initially resistant, some tribal members set aside their traditions and practices to form their own sect.[127][112] Later, European immigrants added other faiths. Christianity is the predominant religion in Buffalo and Western New York. Catholicism (primarily the Latin Church) has a significant presence in the region, with 161 parishes and over 570,000 adherents in the Diocese of Buffalo.[128][معلومات قديمة][129]

A Jewish community began developing in the city with immigrants from the mid-1800s; about one thousand German and Lithuanian Jews settled in Buffalo before 1880. Buffalo's first synagogue, Temple Beth El, was established in 1847.[130] The city's Temple Beth Zion is the region's largest synagogue.[131]

With changing demographics and an increased number of refugees from other areas on the city's East Side,[132] Islam and Buddhism have expanded their presence. In this area, new residents have converted empty churches into mosques and temples.[133] Hinduism maintains a small, active presence in the area, including the town of Amherst.[134]

A 2016 American Bible Society survey reported that Buffalo is the fifth-least "Bible-minded" city in the United States; 13 percent of its residents associate with the Bible.[135]

الاقتصاد

| Rank | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kaleida Health | 8,359 |

| 2 | Catholic Health | 7,623 |

| 3 | M&T Bank | 7,400 |

| 4 | Tops Friendly Markets | 5,374 |

| 5 | Seneca Gaming Corp. | 3,402 |

| 6 | Roswell Park Cancer Institute | 3,328 |

| 7 | GEICO | 3,250 |

| 8 | Wegmans | 3,102 |

| 9 | HSBC Bank USA | 3,000 |

| 10 | General Motors | 2,981 |

The Erie Canal was the impetus for Buffalo's economic growth as a transshipment hub for grain and other agricultural products headed east from the Midwest. Later, manufacturing of steel and automotive parts became central to the city's economy.[137] When these industries downsized in the region, Buffalo's economy became service-based. Its primary sectors include health care, business services (banking, accounting, and insurance), retail, tourism and logistics, especially with Canada.[137] Despite the loss of large-scale manufacturing, some manufacturing of metals, chemicals, machinery, food products, and electronics remains in the region.[138] Advanced manufacturing has increased, with an emphasis on research and development (R&D) and automation.[138] In 2019, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis valued the gross domestic product (GDP) of the Buffalo–Niagara Falls MSA at $53 billion (~$Format price error: cannot parse value "Error when using {{Inflation}}: |index=US-GDP (parameter 1) not a recognized index." in 2022).[139]

The civic sector is a major source of employment in the Buffalo area, and includes public, non-profit, healthcare and educational institutions.[140] New York State, with over 19,000 employees, is the region's largest employer.[141] In the private sector, top employers include the Kaleida Health and Catholic Health hospital networks and M&T Bank, the sole Fortune 500 company headquartered in the city.[142] Most have been the top employers in the region for several decades.[143] Buffalo is home to the headquarters of Rich Products, Delaware North and New Era Cap Company; the aerospace manufacturer Moog Inc. and toy maker Fisher-Price are based in nearby East Aurora. National Fuel Gas and Life Storage are headquartered in Williamsville, New York.

Buffalo weathered the Great Recession of 2006–09 well in comparison with other U.S. cities, exemplified by increased home prices during this time.[144] The region's economy began to improve in the early 2010s, adding over 25,000 jobs from 2009 to 2017.[138] With state aid, Tesla, Inc.'s Giga New York plant opened in South Buffalo in 2017.[145] The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, however, increased the local unemployment rate to 7.5 percent by December 2020.[146] The local unemployment rate had been 4.2 percent in 2019,[147] higher than the national average of 3.5 percent.[148]

The Buffalo area has a larger-than-average pay disparity than the rest of the U.S. The average salary ($43,580) was six percent less than the national average in 2017, with the pay gap increasing to ten percent with increased career specialization.[138] Workforce productivity is higher and turnover lower than other regions.[138]

الثقافة

Performing arts and music

Buffalo is home to over 20 theater companies, with many centered in the downtown Theatre District.[149] Shea's Performing Arts Center is the city's largest theater. Designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany and built in 1926, the theater presents Broadway musicals and concerts.[150] Shakespeare in Delaware Park has been held outdoors every summer since 1976.[151]

Stand-up comedy can be found throughout the city and is anchored by Helium Comedy Club, which hosts both local talent and national touring acts.

The Nickel City Opera (NCO) was founded in 2004 by Valerian Ruminski and performs at Shea's Performing Arts Center.[152] Matthias Manasi was music director of NCO from 2017 to 2021, his predecessor Michael Ching was music director from 2012 to 2017.[153][154] NCO's repertoire consists of a wide range of operas from 18th-century Baroque and 19th-century Bel canto to the Minimalism of the 20th century and to contemporary operas of the 20th and 21st centuries. The NCO has commissioned operas and has staged world premieres of notable works.[155][156]

The Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra was formed in 1935 and performs at Kleinhans Music Hall, whose acoustics have been praised.[157] Although the orchestra nearly disbanded during the late 1990s due to a lack of funding, philanthropic contributions and state aid stabilized it.[158] Under the direction of JoAnn Falletta, the orchestra has received a number of Grammy Award nominations and won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition in 2009.[159]

KeyBank Center draws national music acts year-round. Sahlen Field hosts the annual WYRK Taste of Country music festival every summer with national country music acts. Canalside regularly hosts outdoor summer concerts, a tradition that spun off from the defunct Thursday at the Square concert series.[160][161] Colored Musicians Club, an extension of what was a separate musicians'-union chapter, maintains jazz history.[162]

Rick James was born and raised in Buffalo and later lived on a ranch in the nearby Town of Aurora.[163] James formed his Stone City Band in Buffalo, and had national appeal with several crossover singles in the R&B, disco and funk genres in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[164] Around the same time, the jazz fusion band Spyro Gyra and jazz saxophonist Grover Washington Jr. also got their start in the city.[165][166]

The Goo Goo Dolls, an alternative rock group which formed in 1986, had 19 top-ten singles. Singer-songwriter and activist Ani DiFranco has released over 20 folk and indie rock albums on Righteous Babe Records, her Buffalo-based label.[167]

Underground hip-hop acts in the city partner with Buffalo-based Griselda Records, whose artists include Westside Gunn and Conway the Machine, and occasionally refer to Buffalo culture in their lyrics.[168]

Cuisine

The city's cuisine encompasses a variety of cultures and ethnicities. In 2015, the National Geographic Society ranked Buffalo third on its "World's Top Ten Food Cities" list.[169] Teressa Bellissimo first prepared Buffalo wings (seasoned chicken wings) at the Anchor Bar in 1964.[170] The Anchor Bar has a crosstown rivalry with Duff's Famous Wings, but Buffalo wings are served at many bars and restaurants throughout the city (some with unique cooking styles and flavor profiles).[171][172] Buffalo wings are traditionally served with blue cheese dressing and celery.[172] In 2003, the Anchor Bar received a James Beard Foundation Award in the America's Classics category.[173]

The Buffalo area has over 600 pizzerias, estimated at more per capita than New York City.[174] Several craft breweries began opening in the 1990s, and the city's last call is 4 am.[175] Other mainstays of Buffalo cuisine include beef on weck, butter lambs,[176] kielbasa, pierogi, sponge candy,[177] chicken finger subs (including the stinger - a version that also includes steak), and the fish fry (popular any time of year, but especially during Lent).[178] With an influx of refugees and other immigrants to Buffalo, its number of ethnic restaurants (including the West Side Bazaar kitchen incubator) has increased.[179][180] Some restaurants use food trucks to serve customers, and nearly fifty food trucks appeared at Larkin Square in 2019.[181][180]

Museums and tourism

Buffalo was ranked the seventh-best city in the United States to visit in 2021 by Travel + Leisure, which noted the growth and potential of the city's cultural institutions.[182] The Albright–Knox Art Gallery is a modern and contemporary art museum with a collection of more than 8,000 works, of which only two percent are on display.[183] With a donation from Jeffrey Gundlach, a three-story addition designed by the Dutch architectural firm OMA is under construction and scheduled to open in 2022.[184] Across the street, the Burchfield Penney Art Center contains paintings by Charles E. Burchfield and is operated by Buffalo State College.[185] Buffalo is home to the Freedom Wall, a 2017 art installation commemorating civil-rights activists throughout history.[186] Near both museums is the Buffalo History Museum, featuring artwork, literature and exhibits related to the city's history and major events, and the Buffalo Museum of Science is on the city's East Side.[187][188]

Canalside, Buffalo's historic business district and harbor, attracts more than 1.5 million visitors annually.[189] It includes the Explore & More Children's Museum, the Buffalo and Erie County Naval & Military Park, LECOM Harborcenter, and a number of shops and restaurants. A restored 1924 carousel (now solar-powered) and a replica boathouse were added to Canalside in 2021.[190][191] Other city attractions include the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, the Michigan Street Baptist Church, Buffalo RiverWorks, Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino, Buffalo Transportation Pierce-Arrow Museum, and the Nash House Museum.[161]

The National Buffalo Wing Festival is held every Labor Day at Highmark Stadium.[192] Since 2002, it has served over 4.8 million Buffalo wings and has had a total attendance of 865,000.[193] The Taste of Buffalo is a two-day food festival held in July at Niagara Square, attracting 450,000 visitors annually.[194] Other events include the Allentown Art Festival, the Polish-American Dyngus Day, the Elmwood Avenue Festival of the Arts, Juneteenth in Martin Luther King Jr. Park, the World's Largest Disco in October and Friendship Festival in summer, which celebrates Canada-US relations.[161]

الرياضة

| الرياضة | الاتحاد | النادي | تأسس | الملعب | الألقاب | سنوات البطولة |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| كرة القدم الأمريكية | NFL | Buffalo Bills | 1960 | استاد رالف ويلسون | 2* | 1964، 1965* |

| الهوكي | NHL | Buffalo Sabres | 1970 | First Niagara Center | 0 | |

| البيسبول | IL | Buffalo Bisons | 1979† | Coca-Cola Field | 3 | 1997، 1998، 2004 |

| Lacrosse | NLL | Buffalo Bandits | 1992 | First Niagara Center | 4 | 1992, 1993, 1996, 2008 |

| كرة القدم | NPSL | FC Buffalo | 2009 | Demske Sports Complex | 0 | |

| كرة السلة | PBL | Buffalo 716ers | 2012 | Tapestry Charter School | 0 | |

| هوكي الجليد | NWHL | Buffalo Beauts | 2015 | HarborCenter | 0 |

*

المنتزهات والترفيه

الحكومة

التعليم

البنية التحتية

الرعاية الصحية

Performing arts and music

Buffalo is home to over 20 theater companies, with many centered in the downtown Theatre District.[149] Shea's Performing Arts Center is the city's largest theater. Designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany and built in 1926, the theater presents Broadway musicals and concerts.[195] Shakespeare in Delaware Park has been held outdoors every summer since 1976.[196]

Stand-up comedy can be found throughout the city and is anchored by Helium Comedy Club, which hosts both local talent and national touring acts.

The Nickel City Opera (NCO) was founded in 2004 by Valerian Ruminski and performs at Shea's Performing Arts Center.[197] Matthias Manasi was music director of NCO from 2017 to 2021, his predecessor Michael Ching was music director from 2012 to 2017.[198][199] NCO's repertoire consists of a wide range of operas from 18th-century Baroque and 19th-century Bel canto to the Minimalism of the 20th century and to contemporary operas of the 20th and 21st centuries. The NCO has commissioned operas and has staged world premieres of notable works.[200][201]

The Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra was formed in 1935 and performs at Kleinhans Music Hall, whose acoustics have been praised.[202] Although the orchestra nearly disbanded during the late 1990s due to a lack of funding, philanthropic contributions and state aid stabilized it.[203] Under the direction of JoAnn Falletta, the orchestra has received a number of Grammy Award nominations and won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition in 2009.[204]

KeyBank Center draws national music acts year-round. Sahlen Field hosts the annual WYRK Taste of Country music festival every summer with national country music acts. Canalside regularly hosts outdoor summer concerts, a tradition that spun off from the defunct Thursday at the Square concert series.[205][161] Colored Musicians Club, an extension of what was a separate musicians'-union chapter, maintains jazz history.[206]

Rick James was born and raised in Buffalo and later lived on a ranch in the nearby Town of Aurora.[207] James formed his Stone City Band in Buffalo, and had national appeal with several crossover singles in the R&B, disco and funk genres in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[208] Around the same time, the jazz fusion band Spyro Gyra and jazz saxophonist Grover Washington Jr. also got their start in the city.[209][210]

The Goo Goo Dolls, an alternative rock group which formed in 1986, had 19 top-ten singles. Singer-songwriter and activist Ani DiFranco has released over 20 folk and indie rock albums on Righteous Babe Records, her Buffalo-based label.[211]

Underground hip-hop acts in the city partner with Buffalo-based Griselda Records, whose artists include Westside Gunn and Conway the Machine, and occasionally refer to Buffalo culture in their lyrics.[212]

Cuisine

The city's cuisine encompasses a variety of cultures and ethnicities. In 2015, the National Geographic Society ranked Buffalo third on its "World's Top Ten Food Cities" list.[213] Teressa Bellissimo first prepared Buffalo wings (seasoned chicken wings) at the Anchor Bar in 1964.[214] The Anchor Bar has a crosstown rivalry with Duff's Famous Wings, but Buffalo wings are served at many bars and restaurants throughout the city (some with unique cooking styles and flavor profiles).[215][172] Buffalo wings are traditionally served with blue cheese dressing and celery.[172] In 2003, the Anchor Bar received a James Beard Foundation Award in the America's Classics category.[216]

The Buffalo area has over 600 pizzerias, estimated at more per capita than New York City.[174] Several craft breweries began opening in the 1990s, and the city's last call is 4 am.[175] Other mainstays of Buffalo cuisine include beef on weck, butter lambs,[176] kielbasa, pierogi, sponge candy,[217] chicken finger subs (including the stinger - a version that also includes steak), and the fish fry (popular any time of year, but especially during Lent).[178] With an influx of refugees and other immigrants to Buffalo, its number of ethnic restaurants (including the West Side Bazaar kitchen incubator) has increased.[218][180] Some restaurants use food trucks to serve customers, and nearly fifty food trucks appeared at Larkin Square in 2019.[219][180]

Museums and tourism

Buffalo was ranked the seventh-best city in the United States to visit in 2021 by Travel + Leisure, which noted the growth and potential of the city's cultural institutions.[220] The Albright–Knox Art Gallery is a modern and contemporary art museum with a collection of more than 8,000 works, of which only two percent are on display.[221] With a donation from Jeffrey Gundlach, a three-story addition designed by the Dutch architectural firm OMA is under construction and scheduled to open in 2022.[222] Across the street, the Burchfield Penney Art Center contains paintings by Charles E. Burchfield and is operated by Buffalo State College.[223] Buffalo is home to the Freedom Wall, a 2017 art installation commemorating civil-rights activists throughout history.[224] Near both museums is the Buffalo History Museum, featuring artwork, literature and exhibits related to the city's history and major events, and the Buffalo Museum of Science is on the city's East Side.[225][226]

Canalside, Buffalo's historic business district and harbor, attracts more than 1.5 million visitors annually.[227] It includes the Explore & More Children's Museum, the Buffalo and Erie County Naval & Military Park, LECOM Harborcenter, and a number of shops and restaurants. A restored 1924 carousel (now solar-powered) and a replica boathouse were added to Canalside in 2021.[228][229] Other city attractions include the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, the Michigan Street Baptist Church, Buffalo RiverWorks, Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino, Buffalo Transportation Pierce-Arrow Museum, and the Nash House Museum.[161]

The National Buffalo Wing Festival is held every Labor Day at Highmark Stadium.[230] Since 2002, it has served over 4.8 million Buffalo wings and has had a total attendance of 865,000.[231] The Taste of Buffalo is a two-day food festival held in July at Niagara Square, attracting 450,000 visitors annually.[232] Other events include the Allentown Art Festival, the Polish-American Dyngus Day, the Elmwood Avenue Festival of the Arts, Juneteenth in Martin Luther King Jr. Park, the World's Largest Disco in October and Friendship Festival in summer, which celebrates Canada-US relations.[161]

النقل

Growth and changing transportation needs altered Buffalo's grid plan, which was developed by Joseph Ellicott in 1804. His plan laid out streets like the spokes of a wheel, naming them after Dutch landowners and Native American tribes.[233] City streets expanded outward, denser in the west and spreading out east of Main Street.[234] Buffalo is a port of entry with Canada; the Peace Bridge crosses the Niagara River and links the Niagara Thruway (I-190) and Queen Elizabeth Way.[235] I-190, NY 5 and NY 33 are the primary expressways serving the city, carrying a total of over 245,000 vehicles daily.[ح][236] NY 5 carries traffic to the Southtowns, and NY 33 carries traffic to the eastern suburbs and the Buffalo Airport.[237] The east-west Scajacquada Expressway (NY 198) bisects Delaware Park, connecting I-190 with the Kensington Expressway (NY 33) on the city's East Side to form a partial beltway around the city center.[238] The Scajacquada and Kensington Expressways and the Buffalo Skyway (NY 5) have been targeted for redesign or removal.[239] Other major highways include US 62 on the city's East Side;[240] NY 354 and a portion of NY 130, both east–west routes;[241] and NY 265, NY 266 and NY 384, all north–south routes on the city's West Side.[242] Buffalo has a higher-than-average percentage of households without a car: 30 percent in 2015, decreasing to 28.2 percent in 2016; the 2016 national average was 8.7 percent. Buffalo averaged 1.03 cars per household in 2016, compared to the national average of 1.8.[243]

The Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority (NFTA) operates the region's public transit, including its airport, light-rail system, buses, and harbors. The NFTA operates 323 buses on 61 lines throughout Western New York.[244] Buffalo Metro Rail is a 6.4 mi-long (10.3 km) line which runs from Canalside to the University Heights district. The line's downtown section, south of the Fountain Plaza station, runs at grade and is free of charge.[245] The Buffalo area ranks twenty-third nationwide in transit ridership, with thirty trips per capita per year.[246] Expansions have been proposed since Buffalo Metro Rail's inception in the 1980s, with the latest plan (in the late 2010s) reaching the town of Amherst.[247] Buffalo Niagara International Airport in Cheektowaga has daily scheduled flights by domestic, charter and regional carriers.[248] The airport handled nearly five million passengers in 2019.[249] It received a J.D. Power award in 2018 for customer satisfaction at a mid-sized airport,[250] and underwent a $50 million expansion in 2020–21.[251] The airport, light rail, small-boat harbor and buses are monitored by the NFTA's transit police.[252]

Buffalo has an Amtrak intercity train station, Buffalo–Exchange Street station, which was rebuilt in 2020.[253] The city's eastern suburbs are served by Amtrak's Buffalo–Depew station in Depew, which was built in 1979. Buffalo was a major stop on through routes between Chicago and New York City through the lower Ontario Peninsula; trains stopped at Buffalo Central Terminal, which operated from 1929 to 1979.[254] Intercity buses depart and arrive from the NFTA's Metropolitan Transportation Center on Ellicott Street.[255]

Since Buffalo adopted a complete streets policy in 2008, efforts have been made to accommodate cyclists and pedestrians into new infrastructure projects. Improved corridors have bike lanes,[256] and Niagara Street received separate bike lanes in 2020.[257] Walk Score gave Buffalo a "somewhat walkable" rating of 68 out of 100, with Allentown and downtown considered more walkable than other areas of the city.[258]

المرافق

Buffalo's water system is operated by Veolia Water, and water treatment begins at the Colonel Francis G. Ward Pumping Station.[259] When it opened in 1915, the station's capacity was second only to Paris.[260] Wastewater is treated by the Buffalo Sewer Authority, its coverage extending to the eastern suburbs.[261] National Grid and New York State Electric & Gas (NYSEG) provide electricity, and National Fuel Gas provides natural gas.[262] The city's primary telecommunications provider is Spectrum;[262] Verizon Fios serves the North Park neighborhood. A 2018 report by Ookla noted that Buffalo was one of the bottom five U.S. cities in average download speeds at 66 megabits per second.[263]

The city's Department of Public Works manages Buffalo's snow and trash removal and street cleaning.[264] Snow removal generally operates from November 15 to April 1. A snow emergency is declared by the National Weather Service after a snowstorm, and the city's roads, major sidewalks and bridges are cleared by over seventy snowplows within 24 hours.[265] Rock salt is the principal agent for preventing snow accumulation and melting ice. Snow removal may coincide with driving bans and parking restrictions.[266][267] The area along the Outer Harbor is the most dangerous driving area during a snowstorm;[265] when weather conditions dictate, the Buffalo Skyway is closed by the city's police department.[268]

To prevent ice jams which may impact hydroelectric plants in Niagara Falls, the New York Power Authority and Ontario Power Generation began installing an ice boom annually in 1964. The boom's installation date is temperature-dependent,[269] and it is removed on April 1 unless there is more than 650 km2 (250 sq mi) of ice remaining on eastern Lake Erie.[270] It stretches 2,680 m (8,790 ft) from the outer breakwall at the Buffalo Outer Harbor to the Canadian shore near Fort Erie.[271] Originally made of wood, the boom now consists of steel pontoons.[272]

الإعلام

مشاهير المدينة

العلاقات الدولية

بفلو على توأمة مع عدد من المدن:[273][274]

سيينا، إيطاليا (1961)[273][275]

سيينا، إيطاليا (1961)[273][275] كانازاوا، اليابان (1962)[273][276]

كانازاوا، اليابان (1962)[273][276] دورتموند، ألمانيا (1972)[273][277]

دورتموند، ألمانيا (1972)[273][277] Rzeszów، پولندا (1975)[273][278][279]

Rzeszów، پولندا (1975)[273][278][279] كيپ كوست، غانا (1976)[273]

كيپ كوست، غانا (1976)[273] Aboadze، غانا[273]

Aboadze، غانا[273] Kiryat Gat, Israel (1977)[273]

Kiryat Gat, Israel (1977)[273] Tver, Russia (1989)[273][280]

Tver, Russia (1989)[273][280] Drohobych، اوكرانيا (2000)[273][281]

Drohobych، اوكرانيا (2000)[273][281] ليل، فرنسا (2000)[273][282]

ليل، فرنسا (2000)[273][282] Torremaggiore، إيطاليا (2004)[273][283]

Torremaggiore، إيطاليا (2004)[273][283] أوبجا، نيجريا (2004)[273]

أوبجا، نيجريا (2004)[273] Saint Ann's Bay، جامايكا (2007)[273][284]

Saint Ann's Bay، جامايكا (2007)[273][284]

قنصليات في بفلو

قنصليات فخرية:

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ Foreign entities were not allowed to own land in New York State until 1798 (Goldman 1983a, p. 27).

- ^ Sources disagree on the creek's etymology.[1][2][3] Although its name possibly originated from French fur traders and Native Americans calling the creek Beau Fleuve (French for "beautiful river"),[1][2] Buffalo Creek may have been named after the American buffalo (whose range may have extended into Western New York).[3][38][29]

- ^ When traveling with an ox and wagon team.

- ^ From a 15-percent sample.

- ^ An exception before the mid-20th century was Jewish residents of the East Side during the 1920s, although they left the neighborhood through the 1960s (Goldman 1983b, p. 215).

- ^ Average annual daily traffic, 2019.

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت Stefaniuk, Walter (September 24, 1992). "You asked us: the 868-3900 line to your desk at The Star: how Buffalo got its name". Toronto Star (in الإنجليزية). Toronto, Ont. p. A7. ProQuest 436693160. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Okun, Janice (March 19, 1993). "Worldy setting, sophisticated choices, atmosphere at Beau Fleuve". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). p. G32. ProQuest 380815267. Archived from the original on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Staff (July 21, 1993). "'Beau Fleuve' story doesn't wash". The Buffalo News. p. B9. ProQuest 381587989. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Neville, Anne (August 16, 2009). "Who are we? Queen City, Flour City, Nickel City ... what's with all the nicknames for Buffalo?". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب Powel, Stephen R. (ed.). "First White Settlement and Black Joe - Buffalo, NY". The Buffalonian. Retrieved April 15, 2008. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ Priebe, J. Henry Jr. "The Village of Buffalo - 1801 to 1832". The Buffalonian. Retrieved April 15, 2008. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Erie County Overview". Erie County (New York) Government Home Page. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) Archive copy at the Internet Archive - ^ "Large Metropolitan Statistical Areas—Population: 1990 to 2010" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ "Incorporated Places With 175,000 or More Inhabitants in 2010— Population: 1970 to 2010" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011" (XLS). Population Estimates. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ "Table 1. Rank by Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places, Listed Alphabetically by State: 1790–1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 11, 2012. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Early Railways in Buffalo". The Buffalonian. Retrieved April 16, 2008. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ O'Day, Laura (January 1932). "Buffalo as a Flour Milling Center". Economic Geography. Clark University. 8 (1): pp. 81–93.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ LaChiusa, Chuck. "The History of Buffalo: A Chronology 1971-1985". Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Best Place For Business and Careers". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Buffalo: Economy - Major Industries and Commercial Activity". City-Data.com. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Economic Summary: Western New York Region". New York State Senate. February 18, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archive copy at the Internet Archive

- ^ أ ب ت ث Thompson, John H. (1977). "The Indian". Geography of New York State. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. 113–120. ISBN 9780815621829. LCCN 77004337. OCLC 2874807.

- ^ Ritchie, William A. (19 February 2014). "The Woodland Stage—Development of Ceramics, Agriculture and Village Life". The Archaeology of New York State. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-82049-5.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Rundell, Edwin F.; Stein, Charles W. (1962). "Buffalo's Early History—The Village". Buffalo: your city (4th ed.). Buffalo and Erie County Public Library: Henry Stewart, Incorporated. pp. 57–96. OCLC 3023258.

- ^ Donehoo, George P. (1922). "The Indians of the Past and of the Present". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 46 (3): 177–198. JSTOR 20086480. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ Houghton, Frederick (1927). "The Migrations of the Seneca Nation". American Anthropologist. 29 (2): 241–250. doi:10.1525/aa.1927.29.2.02a00050.

- ^ Alvin M. Josephy, Jr, ed. (1961). The American Heritage Book of Indians. American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc. p. 189. LCCN 61-14871.

- ^ Becker, Sophie C. (1906). "La Salle and The Griffon". Sketches of early Buffalo and the Niagara region. Buffalo, N.Y.: McLaughlin Press. pp. 9–24. OCLC 12629461.

- ^ Brady, Erik (July 8, 2019). "Le Griffon never made it to port but lives on in a Buffalo park and the Canisius mascot". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت French, J. H.; Place, Frank (1860). "Erie County". Gazetteer of the State of New York. Syracuse, N.Y.: R. Pearsall Smith. pp. 279–294. OCLC 682410715.

- ^ Thompson, John H. (1977). "Buffalo". Geography of New York State. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. 407–423. ISBN 9780815621829. LCCN 77004337. OCLC 2874807.

- ^ أ ب Buffalo Historical Society (1882). Semi-centennial Celebration of the City of Buffalo: Address of the Hon. E. C. Sprague Before the Buffalo Historical Society, July 3, 1882 (in الإنجليزية). Buffalo, N.Y.: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. 17–21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Goldman, Mark (1983a). "Ups and Downs during the Early Years of the Nineteenth Century". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 21–56. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Reitano, Joanne R. (2016). "The Empire State: 1790–1830". New York State: peoples, places, and priorities: a concise history with sources. New York: Routledge. pp. 66–96. ISBN 978-1-136-69997-9. OCLC 918135120.

- ^ أ ب Becker, Sophie C. (1906). "Buffalo Village". Sketches of early Buffalo and the Niagara region. Buffalo, N.Y.: McLaughlin Press. pp. 106–117. OCLC 12629461.

- ^ Bingham, Robert W. (1931). "Captain William Johnston". The cradle of the Queen city: a history of Buffalo to the incorporation of the city. Publications, Buffalo Historical Society,v. 31. Buffalo, N.Y.: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. 132–142. hdl:2027/uva.x000743988. OCLC 364308016. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, John H. (1977). "Geography of Expansion". Geography of New York State. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. 140–171. ISBN 9780815621829. LCCN 77004337. OCLC 2874807.

- ^ أ ب Brush, Edward H. (1901). Iroquois Past and Present. Buffalo, N.Y.: Baker, Jones & Co. p. 87.

- ^ Bingham, Robert W. (1931). "The Holland Land Company". The cradle of the Queen city: a history of Buffalo to the incorporation of the city. Publications, Buffalo Historical Society,v. 31. Buffalo, N.Y.: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. 132–143. hdl:2027/uva.x000743988. OCLC 364308016. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Fernald, Frederik Atherton (1910). The index guide to Buffalo and Niagara Falls. The Library of Congress. Buffalo, N.Y.: F. A. Fernald. p. 21. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ Hornaday, William T. (1889). "Geographic Distribution". The Extermination of the American Bison. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 385–386. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ Ketchum, William (1865). "Origin of the Name of Buffalo". An Authentic and Comprehensive History of Buffalo, with Some Account of Its Early Inhabitants, Both Savage and Civilized, Comprising Historic Notices of the Six Nations, Or Iroquois Indians, Vol. II. Buffalo, N.Y.: Rockwell, Baker & Hill. pp. 63–65, 141. ISBN 9780665514968. OCLC 49073883.

- ^ Severance, Frank H. (1902). "The Achievements of Captain John Montresor". In Buffalo Historical Society (ed.). Buffalo Historical Society Publications. Buffalo, NY: Bigelow Brothers. p. 15. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ French, J. H.; Place, Frank (1860). "Chautauque County". Gazetteer of the State of New York. Syracuse, N.Y.: R. Pearsall Smith. pp. 208–217. OCLC 682410715.

- ^ Turner, Orsamus (1849). Pioneer history of the Holland Purchase of western New York. Buffalo, N.Y.: Jewett, Thomas & Co. pp. 401, 439, 494–495, 498. OCLC 14246512.

- ^ Quimby, Robert (1997). The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-87013-441-8. OCLC 868964185.

- ^ Hammill, Luke (November 29, 2017). "The Buffalo of Yesteryear: Chictawauga, Scajaquady and the 'morass' that was Buffalo". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ أ ب Becker, Sophie C. (1906). "The Burning of Buffalo". Sketches of early Buffalo and the Niagara region. Buffalo, N.Y.: McLaughlin Press. pp. 118–132. OCLC 12629461.

- ^ Severance, Frank H. (1879). "Papers relating to the Burning of Buffalo". Publications of the Buffalo Historical Society. Harold B. Lee Library. Buffalo: Bigelow Bros. pp. 334–356.

- ^ "A Brief Chronology of the Development of the City of Buffalo". National Park Service. Archived from the original on نوفمبر 4, 2014. Retrieved أكتوبر 29, 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Goldman, Mark (1983). "Ethnics: Germans, Irish and Blacks". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 72–97. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Rundell, Edwin F.; Stein, Charles W. (1962). "Buffalo Becomes a Great City". Buffalo: your city (4th ed.). Buffalo and Erie County Public Library: Henry Stewart, Incorporated. pp. 97–125. OCLC 3023258.

- ^ Wesley, Charles H. (Jan 1944). "The Participation of Negroes in Anti-Slavery Political Parties". The Journal of Negro History. 29 (1): 43–44, 51–52, 55, 65. doi:10.2307/2714753. JSTOR 2714753. S2CID 149675414.

- ^ Switala, William J. (May 14, 2014). Underground Railroad in New York and New Jersey. Stackpole Books. p. 126. ISBN 9780811746298.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Goldman, Mark (1983). "The Impact of Commerce and Manufacturing on Mid-Nineteenth Century Buffalo". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 56–71. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ أ ب Goldman, Mark (1983). "The Coming of Industry". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 124–142. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Goldman, Mark (1983). "The Response to Industrialization: Life and Labor, Values and Beliefs". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 143–175. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ أ ب Goldman, Mark (1983b). "Ethnics and the Economy During World War I and the 1920s". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 196–223. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Bewley, Michele Ryan (2003). "The New World in Unity: Pan-America Visualized at Buffalo in 1901". New York History. 84 (2): 179–203. ISSN 0146-437X. JSTOR 23183322. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Goldman, Mark (1983). "The Pan American Exposition: World's Fair as Historical Metaphor". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 3–20. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Reitano, Joanne R. (2016). "The Progressive State: 1900–28". New York State: peoples, places, and priorities: a concise history with sources. New York: Routledge. pp. 162–191. ISBN 978-1-136-69997-9. OCLC 918135120.

- ^ Markwyn, Abigail (2018). "Spectacle and Politics in Buffalo and Philadelphia: The World's Fairs of 1901 and 1926". Reviews in American History. 46 (4): 624–630. doi:10.1353/rah.2018.0094. S2CID 150181280. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Gee, Derek (February 24, 2021). "A Closer Look: Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Dillaway, Diana (2006). "Economic Power". Power failure: politics, patronage, and the economic future of Buffalo, New York. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. pp. 25–39. ISBN 978-1591024002.

- ^ أ ب Rundell, Edwin F.; Stein, Charles W. (1962). "Buffalo—Center of Commerce and Industry". Buffalo: your city (4th ed.). Buffalo and Erie County Public Library: Henry Stewart, Incorporated. pp. 149–172. OCLC 3023258.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Reitano, Joanne R. (2016). "The Stressed State: 1954–75". New York State: peoples, places, and priorities: a concise history with sources. New York: Routledge. pp. 223–252. ISBN 978-1-136-69997-9. OCLC 918135120.

- ^ Plesur, Milton; Adler, Selig; Lansky, Lewis (1980). "Buffalo and the Great Depression, 1929–1933". An American historian: essays to honor Selig Adler. Buffalo, N.Y.: State University of New York at Buffalo. pp. 204–213. OCLC 6984440.

- ^ Goldman, Mark (1983). "Paranoia: The Fear of Outsiders and Radicals During the 1950s and 1960s". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 242–266. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Hobor, George (1 October 2013). "Surviving the Era of Deindustrialization: The New Economic Geography of the Urban Rust Belt". Journal of Urban Affairs. 35 (4): 417–434. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00625.x. S2CID 154777044.

- ^ أ ب Thompson, John H. (1977). "Land Forms". Geography of New York State. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. 19–54. ISBN 9780815621829. LCCN 77004337. OCLC 2874807.

- ^ أ ب ت Bryce, S. A.; Griffith, G. E.; Omernik, J. M.; Edinger, G.; Indrick, S.; Vargas, O.; Carlson, D. (2010). Ecoregions of New York (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photograph) (PDF) (Map). 1:1,250,000. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2021.

- ^ "ACME Mapper 2.2: University Heights (689 feet)". ACME Mapper (Map). Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021. and "ACME Mapper 2.2: Fruit Belt (682 feet)". ACME Mapper (Map). Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Luther, D. D. (1906). Geologic map of the Buffalo quadrangle (in الإنجليزية). Columbia University Libraries. New York State Education Department. pp. 12–13.

- ^ "UB Geologists Find Evidence That Upstate New York Is Criss-Crossed By Hundreds Of Faults - University at Buffalo". University at Buffalo (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Dineva, S. (2004-10-01). "Seismicity of the Southern Great Lakes: Revised Earthquake Hypocenters and Possible Tectonic Controls". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 94 (5): 1902–1918. Bibcode:2004BuSSA..94.1902D. doi:10.1785/012003007.

- ^ Smith, Henry Perry (1884). History of the city of Buffalo and Erie County: with ... biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers ... Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co. p. 16.

- ^ "TreeKeeper 8 System for Buffalo, NY". City of Buffalo Bureau of Forestry. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Buffalo city, Erie County, New York". United States Census Bureau. 2020. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (نوفمبر 14, 2008). "Saving Buffalo's Untold Beauty". The New York Times. Archived from the original on أكتوبر 6, 2014. Retrieved سبتمبر 19, 2014.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (سبتمبر 1, 2013). "Louis Sullivan still has a skyscraper in Buffalo, but Chicago has none". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 25, 2015. Retrieved سبتمبر 23, 2015.

- ^ E. Kaplan, Marilyn (يونيو 1989). "Preservation Tech Notes: Guaranty Building" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on يناير 13, 2016. Retrieved سبتمبر 23, 2015.

- ^ Korom, Joseph J. (2008). The American Skyscraper, 1850-1940: A Celebration of Height (in الإنجليزية). Branden Books. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8283-2188-4. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (1982). H. H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works (in الإنجليزية). MIT Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780262650151. OCLC 8389021.

- ^ Buckley, Eileen (June 5, 2018). "Recalling treatment at Buffalo's former mental institution". WBFO (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Miller, Melinda (نوفمبر 17, 2013). "Preparing for 38 floors of emptiness at One Seneca Tower". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 26, 2015. Retrieved سبتمبر 26, 2015.

- ^ "Darwin Martin House State Historic Site". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. State of New York. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Douglas Jemal moves 'full speed ahead' on bevy of Buffalo projects". October 25, 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Goldman, Mark (1983). "The Changing Structure of the City: Neighborhoods and the Rise of Downtown". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 176–195. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin (March 17, 2019). "Fruit Belt fights for its name over fears big tech is erasing it". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021. and Buffalo Urban Renewal Agency. "Neighborhood Profile". Open Data Buffalo (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Herko, Carl (March 14, 1993). "One street, different worlds all along Main, a barrier between the haves and the have-nots". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Lewyn, Michael (2000). "The City of Buffalo And Its Neighborhoods". Car-free in Buffalo: a guide to Buffalo's neighborhoods, suburbs and public transportation. San Jose: Writers Club Press. pp. 35–64. ISBN 0595127053.

- ^ أ ب Sommer, Mark (April 10, 2018). "Elmwood grapples with growth, but there's harmony on Hertel". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Caya, Chris (March 24, 2014). "Brewery's choice typifies growth of Larkinville". WBFO (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2021. and Schneider, Keith (2013-07-31). "Once Just a Punch Line, Buffalo Fights Back". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "Downtown Buffalo: Looking Ahead With A Clearer View" (PDF). Buffalo Niagara Partnership. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Epstein, Jonathan D. (January 28, 2021). "After years of inaction, downtown development is a bustling scene". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ News Editorial Board (November 1, 2019). "Editorial: U-turn on Chandler Street". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Teaman, Rachel (July 9, 2019). "Buffalo Green Code, with a national award, builds on 20 years of planning for place-based urban regeneration". University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Buffalo Climate Narrative". National Weather Service (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ Paul, Don (May 10, 2021). "Don Paul: Weather's 'new normals' are really new averages". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Niziol, Thomas A.; Snyder, Warren R.; Waldstreicher, Jeff S. (1 March 1995). "Winter Weather Forecasting throughout the Eastern United States. Part IV: Lake Effect Snow". Weather and Forecasting. 10 (1): 63–66. Bibcode:1995WtFor..10...61N. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1995)010<0061:WWFTTE>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Blechmen, Jerome B. (1996). "A comparison between mean monthly temperature and mean monthly snowfall in New York State". National Weather Digest. 20 (4): 42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.664.7098.

- ^ Kirst, Sean (December 15, 2016). "Golden Snowball is symbol of upstate winters. So where is it?". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Dewey, Kenneth F. (December 1977). "Lake-effect Snowstorms and the Record Breaking 1976–77 Snowfall to the Lee of Lakes Erie and Ontario". Weatherwise (in الإنجليزية). 30 (6): 230–231. doi:10.1080/00431672.1977.9931836. ISSN 0043-1672. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Freedman, Andrew (January 2007). "Anatomy of a Forecast: 'Arborgeddon' Takes Buffalo by Surprise". Weatherwise (in الإنجليزية). 60 (4): 16–21. doi:10.3200/WEWI.60.4.16-21. ISSN 0043-1672. S2CID 191572229. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Vermette, Stephen (2015-07-04). "Enough Already! Buffalo's Snowvember". Weatherwise (in الإنجليزية). 68 (4): 34–39. doi:10.1080/00431672.2015.1045369. ISSN 0043-1672. S2CID 191715976. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Buffalo Daily Records". National Weather Service (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 29, 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Fortner, Rosanne W; Mayer, Victor J (1987). "The Effect of Lake Erie on Climate". The Great Lake Erie: a reference text for educators and communicators (PDF). Ohio State University Research Foundation. pp. 41, 48. OCLC 22509849. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Census" (PDF). United States Census. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2013. page 36

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on April 12, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Buffalo city, New York". www.census.gov (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ "Buffalo (city), New York". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- ^ أ ب Hauptman, Laurence M. (1999). "Chapter 7: The Lake Effect". Conspiracy of interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. 107, 111–113. ISBN 978-0-8156-0547-8. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Tulke, Julia (2020). "Of Silo Dreams and Deviant Houses: Uneven Geographies of Abandonment in Buffalo, New York". Buffalo at the crossroads: the past, present, and future of American urbanism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9781501749797. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Blatto, Anna (April 2018). "A City Divided: A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo" (PDF). Partnership for the Public Good. pp. 3, 4, 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب Goldman, Mark (1983). "Praying for a Miracle". High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 267–291. ISBN 9780873957342. OCLC 09110713.

- ^ Yin, Li (December 2009). "The Dynamics of Residential Segregation in Buffalo: An Agent-based Simulation". Urban Studies. 46 (13): 2753. doi:10.1177/0042098009346326. S2CID 154853805. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Kraus, Neil (2000). Race, neighborhoods, and community power: Buffalo politics, 1934–1997 (in الإنجليزية). Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0791447437. OCLC 43296770.

[...] Buffalo, one of the most segregated cities in the United States.

- ^ Partnership for the Public Good (June 22, 2015). "From Puerto Rico to Buffalo" (PDF). Partnership for the Public Good. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Ellis, David Maldwyn (1979). "The Peoples of New York". New York: State and City. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780801411809. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSCensusEst2020 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPopEstCBSA - ^ أ ب ت Partnership for the Public Good (February 28, 2018). "Immigrants, Refugees, and Languages Spoken in Buffalo" (PDF). Partnership for the Public Good. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "ACS State and Local Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Statistics". United States Census Bureau (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Raja, Samina; Yadav, Pavan (June 2008). "Beyond Food Deserts: Measuring and Mapping Racial Disparities in Neighborhood Food Environments". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 27 (4): 469. doi:10.1177/0739456X08317461. S2CID 40262352. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Scanlon, Scott (March 27, 2020). "Covid-19 or not, Western New York has serious health issues". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Partnership for the Public Good. "Public Education In Buffalo And The Region" (PDF). Partnership for the Public Good. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Nicholas, Mark A. (2006). "Practicing Local Faith & Local Politics: Senecas, Presbyterianism, and A "New Indian Mission History"". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 73 (1): 69–72. doi:10.2307/pennhistory.73.1.0069. ISSN 0031-4528. JSTOR 27778719. S2CID 157731538. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Herbeck, Dan (May 23, 2020). "Facing huge debts, Buffalo Diocese studies possible mergers of churches, schools". The Buffalo News (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ 2010 U.S. religion census: religious congregations & membership study: an enumeration by nation, state, and county based on data reported for 236 religious groups. Kansas City, Mo.: Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. 2012. p. 397. ISBN 978-0615623443.

- ^ Kotzin, Chana Revell (2013). Jewish community of Greater Buffalo. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 12–16. ISBN 978-1-4671-2006-7.