اللغة المندائية

| المندائية | |

|---|---|

| Mandāyì، الرطنة، ࡓࡀࡈࡍࡀ | |

| موطنها | العراق، إقليم خوزستان في إيران، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية, إضافة إلى كونها اللغة الطقسية للديانة المندائية سواء في بلاد الرافدين أو المهجر |

| العرق | المندائيون |

الناطقون الأصليون | 5,500 (2001–2006)e18 |

الأفرو-آسيوية

| |

الصيغ المبكرة | |

| الأبجدية المندائية | |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either: mid – Mandaic myz – المندائية الكلاسيكية |

mid Neo-Mandaic | |

myz Classical Mandaic | |

| Glottolog | mand1468nucl1706clas1253 |

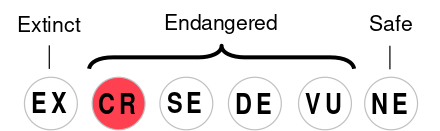

Mandaic is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010)[1] | |

اللغة المندائية هي اللغة الطقسية للديانة المندائية. تستخدم اللغة المندائية الكلاسيكية كلغة طقسية حيث دونت من خلالها الكتب الدينية للديانة الصابئية المندائية. في حين أن اللغة المندائية المحكية و التي تسمى الرطنة هي اللهجة الدارجة من المندائية التي يستخدمها عامة المندائيين في الحياة اليومية رغم انها على حافة الإنقراض حالياً حيث قل استخدامها في الحياة اليومية بشكل كبير, و يجدر بالذكر ان الرطنة يستخدمها مندائيو الأهواز على عكس مندائيي العراق الذين يستخدمون اللهجة العراقية الدارجة في حياتهم اليومية [2] . وتتميز الرطنة بكونها مندائية غير صافية حيث أنها متأثرة بشكل كبير باللغتين العربية و الفارسية. و تصنف اللغة المندائية الكلاسيكية على أنها الفرع الآرامي الشرقي النقي حيث أنها تتميز بصرامتها و عدم تأثرها بأي لهجة أخرى من ناحية القواعد.

تاريخ اللغة المندائية

كانت اللغة المندائية و هي إحدى اللغات الآرامية اللغة المنتشرة في بطائح العراق (جنوب العراق) أو ما يعرف بالسواد قبيل الفتح الإسلامي للعراق. اما في الفترة المعاصرة فيقتصر استخدام اللغة المندائية على الطقوس الدينية و استعمال بسيط في الحياة اليومية قريب من الانقراض. ترابط الفروع المعاصرة للغة الآرامية غامض نوعاً ما و ربما يعود هذا لتطور العديد منها في بيئات منعزلة عن الأخرى مثل لهجات معلولا أو شمال العراق أو الأهواز و جنوب العراق أو منطقة اورمية و لهذا عدت هذه الفروع لغات منفصلة بحد ذاتها. كما أن عملية ربط اللغات الآرامية الحالية باللغة الآرامية القديمة عمل صعب, لكن مع هذا فإن اللغة المندائية تثبت وجود مع مخطوطات بابلية قديمة و مع طريقة تدوين التلمود البابلي.

مناطق الانتشار

تستخدم اللغة المندائية في الطقوس الدينية لدى كافة المندائيين لذا فرض تعلمها على رجال الدين في الديانة المندائية. و قد كانت اللغة المندائية منتشرة في تجمعات سكانية في مدن شوشتر و دزفول و المحمرة(خرمشهر) و الأهواز في اقليم خوزستان في إيران. إضافة إلى رجال الدين الصابئة جنوب العراق. لكن تجمعات السكان المتحدثين بالمندائية قد نزحت من دزفول و شوشتر إلى الاهواز و المحمرة(تعرف حالياً بإسم خرمشهر) بعد مجازر تعرضوا لها خلال ال1880م. مما جعل الخرمشهر و الأهواز أكبر تجمعين للناطقين بالمندائية في العالم. و لكن و بسبب الحرب الفروضة العراقية علی الإيرانية فإن التجمع المندائي في خرمشهر قد ترك المدينة و نزح إلى مدينة الأهواز أو إلى المهجر مما جعل مدينة الأهواز في اقليم خوزستان آخر موقع جغرافي يتواجد فيه تجمع يتحدث المندائية في حياته اليومية.

التأثير في اللهجة العراقية العامية

للمندائية كما للغة الآرامية تأثير كبير في اللغة العراقية المحلية و للمندائية بشكل خاص أثر كبير على اللهجات المحكية في جنوب و وسط العراق بالذات حيث تتداول العديد الكلمات ذات الأصل المندائي في اللهجة العراقية مثل:

- أكو، ماكو و التي تعني يوجد و لا يوجد.

- چا و التي تعني إذاً.

- يمعود، ترجية، طرشي، صاية وصرماية و غيرها [3].

- طٌب و التي تعني أدخل من الفعل المندائي طبا و التي تعني دخل.

الانقراض

اللغة المندائية حالياً على شفير الانقراض حيث أن مجموع من يتحدثون بها حوالي 100 شخص في العالم, 40% منهم من رجال الدين و 10 اشخاص منهم فقط في العراق و البقية في اقليم خوزستان في إيران [3]. لكن و حسب مصدر آخر فإن القادري على التحدث بالمندائية حوالي 500 شخص عام 2001م معظمهم ثنائيي اللغة حيث يتحدثون إما اللغة الفارسية (اللهجة الغربية) أو العربية (اللهجة العراقية أو الأهوازية). كما أن نسبة كبيرة منهم هم من كبار السن. و يتحدث هاؤلاء اللهجة المندائية الأهوازية, في حين أن لهجة شوشتر المندائية يعتقد انها انقرضت أما بالنسبة للهجة المندائية العراقية الحديثة فهي منقرضة في القرن العشرين. كما قد أفاد بعض الآشوريين بوجود متحدثين للغة المندائية في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية حيث يسميهم الآشوريون يوخنّايي [4]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | ||||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tˤ | (t͡ʃ) | k | q | (ʔ) | |||

| voiced | b | d | (dˤ) | (d͡ʒ) | g | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x | (ħ) | h | ||

| voiced | v | ð | z | (zˤ) | (ʒ) | ɣ | (ʕ) | ||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||||

- The glottal stop [ʔ] is said to have disappeared from Mandaic.

- /k/ and /ɡ/ are said to be palatal stops, and are generally pronounced as [c] and [ɟ], but are transcribed as /k, ɡ/, however; they may also be pronounced as velar stops [k, ɡ].

- /x/ and /ɣ/ are noted as velar, but are generally pronounced as uvular [χ] and [ʁ], however; they may also be pronounced as velar fricatives [x, ɣ].

- Sounds [tʃ, dʒ, ʒ] only occur in Arabic and Persian loanwords.

- Both emphatic voiced sounds [dˤ, zˤ] and pharyngeal sounds [ħ, ʕ] only occur in Arabic loanwords.[5]

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | ə | (o) oː |

| ɔ | |||

| Open | æ | a | ɑː |

Alphabet

Mandaic is written in the Mandaic alphabet. It consists of 23 graphemes, with the last being a ligature.[7] Its origin and development is still under debate.[8] Graphemes appearing on incantation bowls and metal amulet rolls differ slightly from the late manuscript signs.[9]

Lexicography

Lexicographers of the Mandaic language include Theodor Nöldeke,[10] Mark Lidzbarski,[11] Ethel S. Drower, Rudolf Macúch,[12] and Matthew Morgenstern.

Neo-Mandaic

Neo-Mandaic represents the latest stage of the phonological and morphological development of Mandaic, a Northwest Semitic language of the Eastern Aramaic sub-family. Having developed in isolation from one another, most Neo-Aramaic dialects are mutually unintelligible and should therefore be considered separate languages. Determining the relationship between Neo-Aramaic dialects is difficult because of poor knowledge of the dialects themselves and their history.[13]

Although no direct descendants of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic survive today, most of the Neo-Aramaic dialects spoken today belong to the Eastern sub-family of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic and Mandaic, among them Neo-Mandaic that can be described with any certainty as the direct descendant of one of the Aramaic dialects attested in Late Antiquity, probably Mandaic. Neo-Mandaic preserves a Semitic "suffix" conjugation (or perfect) that is lost in other dialects. The phonology of Neo-Mandaic is divergent from other Eastern Neo-Aramaic dialects.[14]

Three dialects of Neo-Mandaic were native to Shushtar, Shah Vali, and Dezful in northern Khuzestan Province, Iran before the 1880s. During that time, Mandeans moved to Ahvaz and Khorramshahr to escape persecution. Khorramshahr had the most Neo-Mandaic speakers until the Iran–Iraq War caused many people to leave Iran.[13] Ahvaz is the only community with a sizeable portion of Neo-Mandaic speakers in Iran as of 1993.[15]

The following table compares a few words in Old Mandaic with three Neo-Mandaic dialects. The Iraq dialect, documented by E. S. Drower, is now extinct.[16]

| Meaning | Script | Old Mandaic | Iraq dialect | Ahvaz dialect | Khorramshahr dialect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| house | ࡁࡀࡉࡕࡀ | baita | bejθæ | b(ij)eθa/ɔ | bieθɔ |

| in, ins | ࡁ | b- | gaw; b- | gu | gɔw |

| work | ࡏࡅࡁࡀࡃࡀ | ebada | wad | wɔd | əwɔdɔ |

| planet | ࡔࡉࡁࡉࡀࡄࡀ | šibiaha | ʃewjæ | ʃewjɔha | ʃewjɔhɔ |

| come! (imp.pl) | ࡀࡕࡅࡍ | atun | doθi | d(ij)ɵθi | doθi |

Sample Text

The following is a sample text in Mandaic of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[17]

Mandaic: ".ࡊࡅࡋ ࡀࡍࡀࡔࡀ ࡌࡀࡅࡃࡀࡋࡇ ࡀࡎࡐࡀࡎࡉࡅࡕࡀ ࡅࡁࡊࡅࡔࡈࡂࡉࡀࡕࡀ ࡊࡅࡉ ࡄࡃࡀࡃࡉࡀ. ࡄࡀࡁ ࡌࡅࡄࡀ ࡅࡕࡉࡓࡀࡕࡀ ࡏࡃࡋࡀ ࡏࡉࡕ ࡓࡄࡅࡌ ࡅࡆࡁࡓ ࡁࡄࡃࡀࡃࡉࡀ"

Transliteration: "kul ānāʃā māudālẖ āspāsiutā ubkuʃᵵgiātā kui hdādiā. hāb muhā utirātā ʿdlā ʿit rhum uzbr bhdādiā."

English original: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

See also

- Christian Palestinian Aramaic

- Jewish Palestinian Aramaic

- Samaritan Aramaic language

- Western Aramaic languages

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Mandaic

- أبجدية مندائية

مصادر

- ^ "Atlas of the world's languages in danger". unesdoc.unesco.org. p. 42. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ^ الصابئة المندائيون, الليدي دراوور, ترجمة نعيم بدوي و غضبان رومي, الطبعة الثانية 2005م, صفحة 32.

- ^ أ ب http://nahrain.com/news.php?readmore=2703

- ^ http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=mid

- ^ أ ب Macuch, Rudolf (1965). Handbook of Classical and Modern Mandaic. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- ^ Malone, Joseph (1967). A Morphologic Grammar of the Classical Mandaic Verb. University of California at Berkeley.

- ^ Rudolf Macuch, Handbook of Classical and Modern Mandaic (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1965), p. 9.

- ^ Peter W. Coxon, “Script Analysis and Mandaean Origins,” in Journal of Semitic Studies 15, 1970, pp. 16–30; Alexander C. Klugkist, “The Origin of the Mandaic Script,” in Han L. J. Vanstiphout et al. (eds.), Scripta Signa Vocis. Studies about scripts, scriptures, scribes and languages in the Near East presented to J. H. Hospers (Groningen: E. Forsten, 1986), pp. 111–120; Charles G. Häberl, “Iranian Scripts for Aramaic Languages: The Origin of the Mandaic Script,” in Bulletin for the Schools of American Oriental Research 341, 2006, pp. 53–62.

- ^ Tables and script samples in Christa Müller-Kessler, “Mandäisch: Eine Zauberschale,” in Hans Ulrich Steymans, Thomas Staubli (eds.), Von den Schriften zur (Heiligen) Schrift (Freiburg, CH: Bibel+Orient Museum, Stuttgart Katholisches Bibelwerk e.V., 2012), pp. 132–135, ISBN 978-3-940743-76-3.

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke. 1964. Mandäische Grammatik, Halle: Waisenhaus; reprint Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft with Appendix of annotated handnotes from the hand edition of Theodor Nöldeke by Anton Schall.

- ^ In his masterful translations of several Mandaic Classical works: 1915. Das Johannesbuch. Giessen: Töpelmann; 1920. Mandäische Liturgien (Abhandlungen der königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Phil.-hist. Kl. NF XVII,1) Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung; 1925: Ginza: Der Schatz oder das grosse Buch der Mandäer. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ Ethel S. Drower and Rudolf Macuch. 1963. A Mandaic Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. This work is based on Lidzbarski’s lexicrographical files, today in the University of Halle an der Saale, and Drower’s lexical collection.

- ^ أ ب Charles Häberl, The Neo-Mandaic Dialect of Khorramshahr, (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2009).

- ^ Rudolf Macuch, Neumandäische Chrestomathie (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1989).

- ^ Rudolf Macuch, Neumandäische Texte im Dialekt von Ahwaz (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1993).

- ^ Häberl, Charles G. (2019). "Mandaic". In Huehnergard, John (ed.). The Semitic languages. Abingdon, Oxfordshire; New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 679–710. doi:10.4324/9780429025563-26. ISBN 978-0-367-73156-4. OCLC 1060182406. S2CID 241640755.

- ^ "OHCHR | Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Mandaic". OHCHR (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-01-31.

Literature

- Theodor Nöldeke. 1862. "Ueber die Mundart der Mandäer," Abhandlungen der Historisch-Philologischen Classe der königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen 10: 81–160.

- Theodor Nöldeke. 1964. Mandäische Grammatik, Halle: Waisenhaus; reprint Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft with Appendix of annotated handnotes from the hand edition of Theodor Nöldeke by Anton Schall.

- Svend Aage Pallis. 1933. Essay on Mandaean Bibliography. London: Humphrey Milford.

- Franz Rosenthal. 1939. "Das Mandäische," in Die aramaistische Forschung seit Th. Nöldeke’s Veröffentlichungen. Leiden: Brill, pp. 224–254.

- Ethel S. Drower and Rudolf Macuch. 1963. A Mandaic Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Rudolf Macuch. 1965. Handbook of Classical and Modern Mandaic. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Rudolf Macuch. 1989. Neumandäische Chrestomathie. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz.

- Macuch, Rudolf (1993). Neumandäische Texte im Dialekt von Ahwaz. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3447033827.

- Joseph L. Malone. 1997. Modern and Classical Mandaic Phonology, in Phonologies of Asia and Africa, edited by Alan S. Kaye. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Rainer M. Voigt. 2007."Mandaic," in Morphologies of Asia and Africa, in Phonologies of Asia and Africa, edited by Alan S. Kaye. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Kim, Ronald (2008). "Stammbaum or Continuum? The Subgrouping of Modern Aramaic Dialects Reconsidered". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (3): 505–510.

- Müller-Kessler, Christa (2009). "Mandaeans v. Mandaic Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Charles G. Häberl. 2009. The Neo-Mandaic Dialect of Khorramshahr. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Häberl, Charles G. (2012). "Neo-Mandaic". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 725–737. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Burtea, Bogdan (2012). "Mandaic". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 670–685. ISBN 9783110251586.

External links

- Mandaic lexicon online

- Semitisches Tonarchiv: Tondokument "Ginza Einleitung" — a recording of the opening of the Ginza Rabba spoken by a Mandaean priest.

- Semitisches Tonarchiv: Tondokument "Ahwâz Macuch 01 A Autobiographie" — a recording of autobiographical material by Sâlem Çoheylî in Neo-Mandaic.

- Mandaic.org Information on the Neo-Mandaic Dialect of Khorramshahr