فيكتور أوربان

- الصيغة الأصلية لهذا الاسم الشخصي هي أوربان ڤيكتور. هذه المقالة تستخدم الترتيب الغربي للأسماء.

ڤيكتور أوربان Viktor Orbán | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس وزراء المجر | |

| تولى المنصب 29 May 2010 | |

| الرئيس | |

| النائب | |

| سبقه | Gordon Bajnai |

| في المنصب 8 يوليو 1998 – 27 مايو 2002 | |

| الرئيس | |

| سبقه | گيولا هورن |

| خلـَفه | پيتر مدگيسي |

| President of the Fidesz | |

| تولى المنصب 17 May 2003 | |

| سبقه | János Áder |

| في المنصب 18 April 1993 – 29 January 2000 | |

| سبقه | Office established |

| خلـَفه | László Kövér |

| Member of the National Assembly | |

| تولى المنصب 2 May 1990 | |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | ڤيكتور ميهالي أوربان 31 مايو 1963 Székesfehérvár، المجر |

| الحزب | فيدس |

| الزوج | أنيكو ليڤاي(1986–الآن) |

| الأنجال | Ráhel گاسپار سارة روزا فلورا |

| الوالدان |

|

| الإقامة | Carmelite Monastery of Buda 5. Cinege út, Budapest |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة أوتڤوس ليونارد كلية پمبروك، أكسفورد |

| المهنة |

|

| التوقيع | |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | Viktor Orbán website |

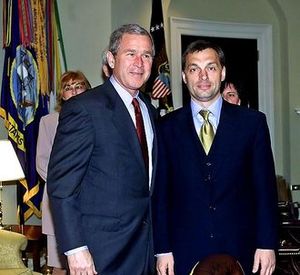

ڤيكتور ميهالي أوربان Viktor Mihály Orbán [1] (النطق في المجرية: [orbaːn viktor ˈmihaːj] (![]() استمع)؛ و. 31 مايو 1963)، هو سياسي مجري، يشغل منصب رئيس وزراء المجر منذ 2010، وكان قد تقلد المنصب من 1998 حتى 2002. أوربان هو زعيم فيدس، حزب محافظ، منذ 1993، مع انقطاع وجيز بين 2000 و 2003.

استمع)؛ و. 31 مايو 1963)، هو سياسي مجري، يشغل منصب رئيس وزراء المجر منذ 2010، وكان قد تقلد المنصب من 1998 حتى 2002. أوربان هو زعيم فيدس، حزب محافظ، منذ 1993، مع انقطاع وجيز بين 2000 و 2003.

Orbán studied at the Faculty of Law of Eötvös Loránd University and briefly at the University of Oxford before entering politics in the wake of the Revolutions of 1989. He headed the reformist student movement the Alliance of Young Democrats (Fiatal Demokraták Szövetsége), the nascent Fidesz. Orbán became nationally known after giving a speech in 1989 in which he openly demanded that Soviet troops leave the country. After the end of Communism in Hungary in 1989 and the country's transition to multiparty democracy the following year, he was elected to the National Assembly and led Fidesz's parliamentary caucus until 1993. Under his leadership, Fidesz shifted away from its original centre-right, classical liberal, pro-European platform toward right-wing, national populism.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Orbán's first term as prime minister, from 1998 to 2002 at the head of a conservative coalition government, was dominated by the economy and Hungary's entry into NATO. He served as Leader of the Opposition from 2002 to 2010. In 2010, Orbán was again elected prime minister. Central issues during Orbán's second premiership have included major constitutional and legislative reforms, in particular the 2013 amendments to the Constitution of Hungary, as well as the European migrant crisis, the lex CEU, and the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary. He was reelected in 2014, 2018, and 2022. On 29 November 2020, he became the country's longest-serving prime minister.[2]

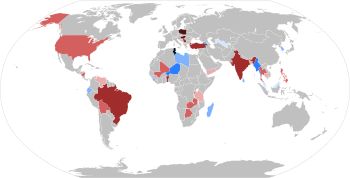

Because of Orbán's curtailing of press freedom, erosion of judicial independence, and undermining of multiparty democracy, many political scientists and watchdogs consider Hungary to have experienced democratic backsliding during Orbán's tenure.[3][4][5] Orbán's harsh criticism of the policies favored by the European Union while accepting their money and funneling it to his allies and family have also led to accusations that his government is a kleptocracy.[6] His government has also been characterized as an autocracy.[7] Between 2010 and 2020, Hungary dropped 69 places in the Press Freedom Index,[8][9] and lost 11 places in the Democracy Index (The Economist);[10][11] Freedom House has downgraded the country from "free" to "partly free".[12] The V-Dem Democracy indices rank Hungary 2023 as 96th electoral democracy in the world.[13] Orbán defends his policies as "illiberal Christian democracy".[14][15] As a result, Fidesz was suspended from the European People's Party from March 2019;[16] in March 2021, Fidesz left the EPP over a dispute over new rule-of-law language in the latter's bylaws.[17] In a July 2022 speech, Orbán criticized the miscegenation of European and non-European races, saying: "We [Hungarians] are not a mixed race and we do not want to become a mixed race."[18][19] Two days later in Vienna, he clarified that he was talking about cultures and not about race.[20] His tenure has seen Hungary's government shift towards what he has called "illiberal democracy", citing countries such as China, Russia, India, Singapore, Israel and Turkey as models of governance, while simultaneously promoting Euroscepticism and opposition to Western democracy and establishment of closer ties with China and Russia.[21][22][23] في انتخابات 2010، مع حزب الشعب الديمقراطي المسيحي، فاز بنسبة 52.73% من الأصوات وحاز على ثلاثي الأغلبية في مقاعد البرلمان المجري.

النشأة

Orbán was born on 31 May 1963 in Székesfehérvár into a rural middle-class family as the eldest son of the agronomist and businessman Győző Orbán (born 1940)[24] and the special educator and speech therapist, Erzsébet Sípos (born 1944).[25] He has two younger brothers, both businessmen, Győző, Jr. (born 1965) and Áron (born 1977). His paternal grandfather, Mihály Orbán, practiced farming and animal husbandry. Orbán spent his childhood in two nearby villages, Alcsútdoboz and Felcsút in Fejér County;[26] he attended school there and in Vértesacsa.[27][28] In 1977, his family moved permanently to Székesfehérvár.[29] At the age of 14 and 15, while at his secondary grammar school, he was a secretary of the communist youth organization, KISZ, membership of which was mandatory in order to matriculate to a university.[30][31]

Orbán graduated from Blanka Teleki High School in Székesfehérvár in 1981, where he studied English. He then completed two years of military service.[32] He later said in an interview that before this time he had considered himself a "naive and devoted supporter" of the Communist regime, but during his military service his political views had changed radically.[33]

Next, in 1983, Orbán went to study law at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest. He wrote his thesis on the Polish Solidarity movement.[32] After obtaining his higher degree of Juris Doctor[34] in 1987,[35][36] he lived in Szolnok for two years, commuting to his job in Budapest as a sociologist at the Management Training Institute of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food.[37]

In 1989, Orbán received a scholarship from the Soros Foundation to study political science at Pembroke College, Oxford.[28] His personal tutor was the Hegelian political philosopher Zbigniew Pełczyński.[38] In January 1990, he left Oxford and returned to Hungary to run for a seat in Hungary's first post-communist parliament.[39]

Early career (1988–1998)

On 30 March 1988, Orbán was one of the founding members of Fidesz (originally an acronym for Fiatal Demokraták Szövetsége, "Alliance of Young Democrats")[40] and served as its first spokesperson. The first members of the party, including Orbán, were mostly students from the Bibó István College for Advanced Studies who opposed the Communist regime.[41] At the college, itself a part of Eötvös Loránd University,[42] Orbán also co-founded the dissident social science journal Századvég.[43]

On 16 June 1989, Orbán gave a speech in Heroes' Square, Budapest, on the occasion of the reburial of Imre Nagy and other national martyrs of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. In his speech, he demanded free elections and the withdrawal of Soviet troops. The speech brought him wide national and political acclaim. In summer 1989, he took part in the opposition round table talks, representing Fidesz alongside László Kövér.[44]

On returning home from Oxford, he was elected Member of Parliament from his party's Pest County Regional List during the 1990 parliamentary election. He was appointed leader of the Fidesz's parliamentary group, serving in this capacity until May 1993.[45]

On 18 April 1993, Orbán became the first president of Fidesz, replacing the national board that had served as a collective leadership since its founding. Under his leadership, Fidesz gradually transformed from a radical liberal student organization to a center-right people's party.[46]

The conservative turn caused a severe split in the membership. Several members left the party, including Péter Molnár, Gábor Fodor and Zsuzsanna Szelényi. Fodor and others later joined the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ), initially a strong ally of Fidesz, but later a political opponent.[47]

During the 1994 parliamentary election, Fidesz barely reached the 5% threshold.[48] Orbán became MP from his party's Fejér County Regional List.[45] He served as chairman of the Committee on European Integration Affairs between 1994 and 1998.[45] He was also a member of the Immunity, Incompatibility and Credentials Committee for a short time in 1995.[45] Under his presidency, Fidesz adopted "Hungarian Civic Party" (Magyar Polgári Párt) to its shortened name in 1995. His party gradually became dominant in the right-wing of the political spectrum, while the former ruling conservative Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) had lost much of its support.[48] From April 1996, Orbán was chairman of the Hungarian National Committee of the New Atlantic Initiative (NAI).[49]

In September 1992, Orbán was elected vice chairman of the Liberal International.[50] In November 2000, however, Fidesz left the Liberal International and joined the European People's Party (EPP). During the time, Orbán worked hard to unite the center-right liberal conservative parties in Hungary. At the EPP's Congress in Estoril in October 2002, he was elected vice-president, an office he held until 2012.[51]

أول رئاسة للوزراء (1998–2002)

In 1998, Orbán formed a coalition with the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) and the Independent Smallholders' Party (FKGP). The coalition won the 1998 parliamentary elections with 42% of the national vote.[51] Orbán became the second youngest prime minister of Hungary at the age of 35 (after András Hegedüs)[52] and the first post-Cold War head of government in both eastern and central Europe who had not previously been a member of a communist party during the Soviet-era.[7]

The new government immediately launched a radical reform of state administration, reorganizing ministries and creating a superministry for the economy. In addition, the boards of the social security funds and centralized social security payments were dismissed. Following the German model, Orbán strengthened the prime minister's office and named a new minister to oversee the work of his Cabinet.[53]

In February the government decided that plenary sessions of the Hungarian Parliament would be held only every third week.[54] Opposition parties strongly opposed the change,[55][56][57] arguing that it would reduce parliament's legislative efficiency and ability to supervise the government.[58] In March, the government also tried to replace the National Assembly rule that requires a two-thirds majority vote with one of a simple majority, but the Constitutional Court ruled this unconstitutional.[59]

The year saw only minor changes in top government officials. Two of Orbán's state secretaries in the prime minister's office had to resign in May, due to their implication in a bribery scandal involving the American military manufacturer Lockheed Martin Corporation. Before bids on a major jet-fighter contract, the two secretaries, along with 32 other deputies of Orbán's party, had sent a letter to two US senators to lobby for the appointment of a Budapest-based Lockheed manager to be the US ambassador to Hungary.[60] On 31 August, the head of the Tax Office also resigned after protracted criticism by the opposition on his earlier, allegedly suspicious, business dealings.[بحاجة لمصدر] The government was also involved in a lengthy dispute with Budapest City Council the national government's decision in late 1998 to cancel two major urban projects: the construction of a new national theatre[61] and of the fourth subway line.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Relations between the Fidesz-led coalition government and the opposition worsened in the National Assembly, where the two seemed to have abandoned all attempts at consensus-seeking politics. The government pushed to swiftly replace the heads of key institutions (such as the Hungarian National Bank chairman, the Budapest City Chief Prosecutor and the Hungarian Radio) with partisan figures. Although the opposition resisted, for example by delaying their appointing of members of the supervising boards, the government ran the institutions without the stipulated number of directors. In a similar vein, Orbán failed to show up for question time in parliament for periods of up to 10 months. His statements such as, "The parliament works without opposition too..." also contributed to the image of arrogant and aggressive governance.[62]

A later report in March by the Brussels-based International Federation of Journalists criticized the Hungarian government for improper political influence in the media, as the country's public service broadcaster teetered close to bankruptcy.[63] Numerous political scandals during 2001 led to a de facto, if not actual, breakup of the coalition that held power in Budapest. A bribery scandal in February triggered a wave of allegations and several prosecutions against the Independent Smallholders' Party. The affair resulted in the ousting of József Torgyán from both the FKGP presidency and the top post in the Ministry of Agriculture. The FKGP disintegrated and more than a dozen of its MPs joined the government faction.[64]

الاقتصاد

Orbán's economic policy was aimed at cutting taxes and social insurance contributions, while reducing inflation and unemployment. Among the new government's first measures was to abolish university tuition fees and reintroduce universal maternity benefits. The government announced its intention to continue the Socialist–Liberal stabilization program and pledged to narrow the budget deficit, which had grown to 4.5% of GDP.[65] The previous Socialist government had almost completed the privatization of government-run industries and had launched a comprehensive pension reform. However, the Socialists had avoided two major socioeconomic issues: reform of health care and agriculture; these remained to be tackled by Orbán's government.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Economic successes included a drop in inflation from 15% in 1998 to 7.8% in 2001. Annual GDP growth rates were fairly steady under Orbán's tenure, ranging from 3.8% to 5.2%. The fiscal deficit fell from 3.9% in 1999 to 3.4% in 2001 and the ratio of the national debt decreased to 54% of GDP.[65] Under the Orbán cabinet, there were realistic hopes that Hungary would be able to join the Eurozone by 2009. However, negotiations for entry into the European Union slowed in the fall of 1999, after the EU included six more countries (in addition to the original six) in the accession discussions. Orbán repeatedly criticized the EU for its delay.[بحاجة لمصدر]

السياسة الخارجية

In March 1999, after Russian objections were overruled, Hungary joined NATO along with the Czech Republic and Poland.[66] The Hungarian membership to NATO demanded its involvement in Federal Republic of Yugoslavia's Kosovo crisis and modernization of its army. NATO membership also dealt a blow to the economy because of a trade embargo imposed on Yugoslavia.[67]

Hungary attracted international media attention in 1999 for passing the "status law" concerning estimated three-million ethnic Hungarian minorities in neighbouring Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia and Ukraine. The law aimed to provide education, health benefits and employment rights to members of those minorities, and was said to heal the negative effects of the disastrous 1920 Trianon Treaty.[68]

Governments in neighbouring states, particularly Romania, claimed to be insulted by the law, which they saw as interference in their domestic affairs. Proponents of the status law countered that several of the countries criticizing the law themselves had similar constructs to provide benefits for their own minorities. Romania acquiesced after amendments following a December 2001 agreement between Orbán and Romanian Prime Minister Adrian Năstase;[69] Slovakia accepted the law after further concessions made by the new government after the 2002 elections.[70]

زعيم المعارضة (2002–2010)

The level of public support for political parties generally stagnated, even with general elections coming in 2002. Fidesz and the main opposition Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) ran neck and neck in the opinion polls for most of the year, both attracting about 26% of the electorate. According to a September 2001 poll by the Gallup organization, however, support for a joint Fidesz – Hungarian Democratic Forum party list would run up to 33% of the voters, with the Socialists drawing 28% and other opposition parties 3% each.[71]

Meanwhile, public support for the FKGP plunged from 14% in 1998 to 1% in 2001. As many as 40% of the voters remained undecided, however. Although the Socialists had picked their candidate for prime minister—former finance minister Péter Medgyessy—the opposition largely remained unable to increase its political support.[بحاجة لمصدر] The dark horse of the election was the radical nationalist Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP), with its leader, István Csurka's radical rhetoric. MIÉP could not be ruled out as the key to a new term for Orbán and his party should they be forced into a coalition after the 2002 elections.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The elections of 2002 were the most heated Hungary had experienced in more than a decade, and an unprecedented cultural-political division formed in the country. In the event, Orbán's group lost the April parliamentary elections to the opposition Hungarian Socialist Party, which set up a coalition with its longtime ally, the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats. Turnout was a record-high 70.5%. Beyond these parties, only deputies of the Hungarian Democratic Forum made it into the National Assembly. The populist Independent Smallholders' Party and the right Hungarian Justice and Life Party lost all their seats. Thus, the number of political parties in the new assembly was reduced from six to four.[72]

MIÉP challenged the government's legitimacy, demanded a recount, complained of election fraud, and generally kept the country in election mode until the October municipal elections. The socialist-controlled Central Elections Committee ruled that a recount was unnecessary, a position supported by observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, whose only substantive criticism of the election conduct was that the state television carried a consistent bias in favour of Fidesz.[73]

Orbán received the Freedom Award of the American Enterprise Institute and the New Atlantic Initiative (2001), the Polak Award (2001), the Grand Cross of the National Order of Merit (2001), the "Förderpreis Soziale Marktwirtschaft" (Price for the Social Market Economy, 2002) and the Mérite Européen prize (2004). In April 2004, he received the Papal Grand Cross of the Order of St. Gregory the Great.

In the 2004 European Parliament election, the ruling Hungarian Socialist Party was heavily defeated by the opposition conservative Fidesz. Fidesz gained 47.4% of the vote and 12 of Hungary's 24 seats.[74][75]

Orbán was the Fidesz candidate for the parliamentary election in 2006. Fidesz and its new-old candidate failed again to gain a majority in this election, which initially put Orbán's future political career as the leader of Fidesz in question.[76] However, after fighting with the Socialist-Liberal coalition, Orbán's position resolidified, and he was elected president of Fidesz for yet another term in May 2007.[77]

On 17 September 2006, an audio recording surfaced from a closed-door Hungarian Socialist Party meeting, which was held on 26 May 2006, in which Hungarian Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány gave an obscenity-laden speech. The leak ignited mass protests.[بحاجة لمصدر] On 1 November, Orbán and his party announced their plans to stage several large-scale demonstrations across Hungary on the anniversary of the Soviet suppression of the 1956 Revolution. The events were intended to serve as a memorial to the victims of the Soviet invasion and a protest against police brutality during the 23 October unrest in Budapest. Planned events included a candlelight vigil march across Budapest. However, the demonstrations were small and petered out by the end of the year.[78] A new round of demonstrations expected in the spring of 2007 did not materialize.[بحاجة لمصدر]

On 1 October 2006, Fidesz won the municipal elections, which counterbalanced the MSZP-led government's power to some extent. Fidesz won 15 of 23 mayoralties in Hungary's largest cities—although it narrowly lost Budapest to the Liberal Party—and majorities in 18 of 20 regional assemblies.[79][80]

On 9 March 2008, a national referendum took place on revoking government reforms which introduced doctor fees per visit and medical fees paid per number of days spent in hospital as well as tuition fees in higher education. Fidesz initiated the referendum against the ruling MSZP.[81][82] The procedure for the referendum started on 23 October 2006, when Orbán announced they would hand in seven questions to the National Electorate Office, three of which (on abolishing copayments, daily fees and college tuition fees) were officially approved on 17 December 2007 and called on 24 January 2008. The referendum passed, a significant victory for Fidesz.[83]

In the 2009 European Parliament election, Fidesz won by a large margin, garnering 56.36% of votes and 14 of Hungary's 22 seats.[84]

Second premiership (2010–present)

During the 2010 parliamentary elections, Orbán's party won 52.73% of the popular vote, with a two-thirds majority of seats, which gave Orbán enough authority to change the Constitution.[85] As a result, Orbán's government drafted and passed a new constitution in 2011.[86][87][88][89] Among other changes, it includes support for traditional values, nationalism, references to Christianity, and a controversial electoral reform, which lowered the number of seats in the Parliament of Hungary from 386 to 199.[90][91] The new constitution entered into force on 1 January 2012 and was later amended further.

In his second term as prime minister, he garnered controversy for his statements against liberal democracy, for proposing an "internet tax", and for his perceived corruption.[92] His second premiership has seen numerous protests against his government, including one in Budapest in November 2014 against the proposed "internet tax".[93]

In terms of domestic legislation, Orbán's government implemented a flat tax on personal income. This tax is set at 16%.[94] Orbán has called his government "pragmatic", citing restrictions on early retirement in the police force and military, making welfare more transparent, and a central banking law that "gives Hungary more independence from the European Central Bank".[95]

After the 2014 parliamentary election, Fidesz won a majority, garnering 133 of the 199 seats in the National Assembly.[96] While he won a large majority, he garnered 44.54% of the national vote, down from 52.73% in 2010.[بحاجة لمصدر]

During the 2015 European migrant crisis, Orbán ordered the erection of the Hungary–Serbia barrier to block entry of illegal immigrants[97] so that Hungary could register all the migrants arriving from Serbia, which is the country's responsibility under the Dublin Regulation, a European Union law. Under Orbán, Hungary took numerous actions to combat illegal immigration and reduce refugee levels.[98] In May 2020, the European Court of Justice ruled against Hungary's policy of migrant transit zones, which Orbán subsequently abolished while also tightening the country's asylum rules.[99]

In the 2018 Hungarian parliamentary election, the Fidesz–KDNP alliance was victorious and preserved its two-thirds majority, with Orbán remaining prime minister. Orbán and Fidesz campaigned primarily on the issues of immigration and foreign meddling, and the election outcome was seen as a victory for right-wing populism in Europe.[100][101][102]

On 30 March 2020, the Hungarian parliament voted 137 to 53 in favor of passing legislation that would create a state of emergency without a time limit, grant the prime minister the ability to rule by decree, suspend by-elections, and introduce the possibility of prison sentences for spreading fake news and sanctions for leaving quarantine.[103][104][105] Two and a half months later, on 16 June 2020, the Hungarian parliament passed a bill that ended the state of emergency effective 19 June.[106] However, on the same day the parliament passed a new law removing the requirement of parliamentary approval for future "medical" states of emergencies, allowing the government to declare them by decree.[107][108]

In 2021, the parliament transferred control of 11 state universities to foundations led by allies of Orbán.[109][110] The Mathias Corvinus Collegium, a residential college, received an influx of government funds and assets equal to about 1% of Hungary's gross domestic product, reportedly as part of a mission to train future conservative intellectuals.[111]

Due to a combination of unfavourable conditions, which involved soaring demand of natural gas, its diminished supply from Russia and Norway to the European markets, and less power generation by renewable energy sources such as wind, water and solar energy, Europe faced steep increases in energy prices in 2021. In October 2021, Orbán blamed a record-breaking surge in energy prices on the European Commission's Green Deal plans.[112]

In the 2022 parliamentary election, Fidesz won a majority, garnering 135 of the 199 seats in the National Assembly. While Orbán's close ties with Moscow raised concerns, core Fidesz voters were persuaded that mending ties with the EU might also lead Hungary into war. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe dispatched a full-scale monitoring mission for the election.[113] Orbán declared victory on Sunday night, with partial results showing his Fidesz party leading the vote by a wide margin. Addressing his supporters after the partial results, Orbán said: "We won a victory so big that you can see it from the moon, and you can certainly see it from Brussels".[4] Opposition leader Péter Márki-Zay admitted defeat shortly after Orbán's speech.[114] Reuters described it as a "crushing victory", which also came as a relief for Warsaw's nationalist Law and Justice government.[113]

Anti-LGBT policies

Since his election as prime minister in 2010, Orbán has led initiatives and laws to hinder human rights of LGBT+ people, regarding such rights as "not compatible with Christian values."

In 2020, Orbán's government ended legal recognition of transgender people, receiving criticism both in Hungary and abroad.[115]

In 2021 his party proposed legislation to censor any "LGBT+ positive content" in movies, books or public advertisements and to severely restrict sex education in school forbidding any information thought to "encourage gender change or homosexuality". The law has been likened to Russia's restriction on "homosexual propaganda."[116] German Chancellor Angela Merkel and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen harshly criticized the law,[117] while a letter from sixteen EU leaders including Pedro Sánchez and Mario Draghi warned against “threats against fundamental rights and in particular the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation”.[118]

His anti-LGBT+ positions came under more scrutiny after the revelation that one of the European deputies of his party, József Szájer, had participated in a gay sex party in Brussels, despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic quarantine restrictions.[119][120][121] Szájer was one of the major architects behind the 2011 Constitution of Hungary. This new constitution has been criticized by Human Rights Watch for being discriminatory towards the LGBT+ community.[122][123]

To coincide with the parliamentary election in the spring of 2022, Orbán announced a four-question referendum regarding LGBTQ issues in education. It did not pass.[124] It came after complaints from the European Union (EU) about anti-LGBTQ discriminatory laws.[125] Human rights groups condemned the referendum as anti-LGBT rhetoric that supported discrimination.[126][127]

On July 22, 2023, in a speech he gave in Romania, Orbán complained that the EU was conducting an “LGBTQ offensive”.[128]

Foreign policy

In July 2018, Orbán travelled to Turkey to attend the inauguration ceremony of re-elected Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[129] In October 2018, Orbán said after talks with President Erdoğan in Budapest that "A stable Turkish government and a stable Turkey are a precondition for Hungary not to be endangered in any way due to overland migration."[130]

In June 2019, Orbán met Myanmar's State Counsellor and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi. They discussed bilateral ties and illegal migration.[131][132]

China

Orbán has maintained close ties with China throughout his tenure, and his administration is generally seen as China's closest ally in the EU.[133] Hungary joined China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2015,[134] while in April 2019, Orbán attended a BRI forum in Beijing,[135] where he met the Chinese leader Xi Jinping.[136] He spearheaded plans to open a Fudan University campus in Budapest, which led to pushback in Hungary.[137] He met with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Politburo member and top diplomat Wang Yi in Budapest on 20 February 2023; he afterwards backed the peace plan released Wang Yi concerning Russia's invasion of Ukraine.[138]

Russia and Ukraine

Orbán questioned Nord Stream II, a new Russia–Germany natural gas pipeline. He said he wants to hear a "reasonable argument why South Stream was bad and Nord Stream is not".[139] "South Stream" refers to the Balkan pipeline cancelled by Russia in December 2014 after obstacles from the EU.[140]

Since 2017, Hungary's relations with Ukraine rapidly deteriorated over the issue of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine.[141] Orbán and his cabinet ministers repeatedly criticized Ukraine's 2017 education law, which makes Ukrainian the only language of education in state schools,[142][143] and threatened to block further Ukraine's EU and NATO integration until it is modified or repealed.[144]

Orbán has displayed an ambivalent attitude towards Russia and Vladimir Putin, especially following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.[145][146] He has described the war as "clear aggression" by Russia, saying a sovereign Ukraine is needed “to stop Russia posing a threat to the security of Europe."[147][148][149] Conversely, he has criticised the European Union for "prolonging the war" in Ukraine by sanctioning Russia and sending weapons and money to Ukraine instead of encouraging a negotiated peace, and has been accused of blocking aid to Ukraine.[150][151]

Amidst the 2021-2022 Ukraine crisis, Orbán was the first EU leader to meet with Vladimir Putin in Moscow in a visit he called "a peacekeeping mission".[152] They also discussed Russian gas exports to Hungary.[114] On 2 March, as Russia had already launched an invasion of Ukraine, Orbán decided to welcome Ukrainian refugees to Hungary, and will support the Ukrainian membership to the European Union.[114] Initially, Orbán condemned Russia's invasion of Ukraine and said Hungary would not veto EU sanctions against Russia.[153] However, Orbán rejected sanctions on Russian energy, due to Hungary's excessive dependency (85%) on Russian fossil fuels.[154] In late March 2022, Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky singled out Orban for his lack of support for Ukraine.[155] In June, Zelensky thanked Orbán for supporting Ukraine's sovereignty and for giving asylum to Ukrainians.[156]

On 27 February 2023, Victor Orbán said that Hungary supports the Chinese peace plan in the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, despite opposition by Western leaders. Beijing's 12-point statement that criticised unilateral sanctions, would reduce strategic risks associated with nuclear weapons in Central and Eastern Europe, according to the statement.[157]

انضمام المجر لمنظمة الدول التوركية

Since 2014, Hungary has had observer status at the General Assembly of Turkic-speaking States, and in 2017 it submitted an application for accession to the International Turkic Academy. During the 6th Summit of Turkic Council, Orbán said that Hungary is seeking even closer cooperation with the Turkic Council.[158] In 2018, Hungary obtained observer status in the council.[159] In 2021, Orbán mentioned that the Hungarian and Turkic peoples share a historical and cultural heritage "reaching back many long centuries". He also pointed out that the Hungarian people are "proud of this heritage, and "were also proud when their opponents in Europe mocked them as barbarian Huns and Attila's people".[160]

Nationalistic views

In his 2018 speech at the meeting of the Association of Cities with County Rights, Orbán said "We must state that we do not want to be diverse and do not want to be mixed: we do not want our own colour, traditions and national culture to be mixed with those of others. We do not want this. We do not want that at all. We do not want to be a diverse country."[161][162]

In his 2021 speech, Orbán said "The challenge with Bosnia is how to integrate a country with 2 million Muslims". Bosnian leaders responded by calling for Orbán's visit to Sarajevo to be cancelled. The head of the country's Islamic Community, Husein Kavazović, characterized his statement as "xenophobic and racist".[163][164]

In May 2022, Orbán promoted the Great Replacement conspiracy theory in a speech.[165]

In July 2022, Orbán – repeating the thesis of Jean Raspail[166][167] – spoke in Romania against the "mixing" of European and non-European races, adding "We [Hungarians] are not a mixed race and we do not want to become a mixed race".[168][169][170][171] In Vienna two days later, he clarified that he was talking about cultures and not about race.[20]

- Opposition to immigration, support for higher birth rates

As stated by The Guardian, the "Hungarian government doubled family spending between 2010 and 2019," intending to achieve "a lasting turn in demographic processes by 2030." Orbán has espoused an anti-immigration platform, and has also advocated for increased investment into "Family First." Orbán has disregarded the European Union's attempts to promote integration as a key solution to population distribution problems in Europe. He has also supported investments into countering the country's low birth rates. Orbán has tapped into the "great replacement theory" which emulates a nativist approach to rejecting foreign immigration out of fear of replacement by immigrants. He has stated that "If Europe is not going to be populated by Europeans in the future and we take this as given, then we are speaking about an exchange of populations, to replace the population of Europeans with others." The Guardian stated that "This year the Hungarian government introduced a 10 million forint (£27,000) interest-free loan for families, which does not have to be paid back if the couple has three children."[172]

In July 2020, Orbán expressed that he still expects arguments over linking of disbursement of funds of the European Union to rule-of-law criteria but remarked in a state radio interview that they "didn't win the war, we (they) won an important battle."[173] In August 2020, Orbán whilst speaking at an event to inaugurate a monument commemorating the Treaty of Trianon, said Central European nations should come together to preserve their Christian roots as western Europe experiments with same-sex families, immigration and atheism.[174]

Despite the anti-immigration rhetoric from Orbán, Hungary increased the immigration of foreign workers into the country as of 2019 to address a labor shortage.[175][176][177]

Views, public image, international influence

Orbán's blend of soft Euroscepticism, populism,[178][179][180] and national conservatism has seen him compared to politicians and political parties as diverse as Jarosław Kaczyński's Law and Justice, Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, Matteo Salvini's League, Marine Le Pen's National Rally, Donald Trump,[181] Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Vladimir Putin.[182] Orbán has sought to make Hungary an "ideological center for ... an international conservative movement."[183]

According to Politico, Orbán's political philosophy "echoes the resentments of what were once the peasant and working classes" by promoting an "uncompromising defense of national sovereignty and a transparent distrust of Europe's ruling establishments".[181] Orbán frequently emphasizes the importance of Christianity, although he and the overwhelming majority of Hungarians do not attend church regularly.[184] His authoritarian appeal to "global conservatives" has been summarized by Lauren Stokes as: "I alone can save you from the ravages of Islamization and totalitarian progressivism -- and in the face of all that, who has time for checks and balances and rules?"[184]

Orbán had a close relationship with the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, having known him for decades. He is described as "one of Mr Netanyahu's closest allies in Europe."[185] Orbán received personal advice on economic reforms from Netanyahu, while the latter was Finance Minister of Israel (2003–2005).[186] In February 2019, Netanyahu thanked Orbán for "deciding to extend the embassy of Hungary in Israel to Jerusalem".[187]

Orbán is seen as having laid out his political views most concretely in a widely cited 2014 public address at Băile Tușnad (known in Hungary as the Tusnádfürdői beszéd, or "Tusnádfürdő speech"). In the address, Orbán repudiated the classical liberal theory of the state as a free association of atomistic individuals, arguing for the use of the state as the means of organizing, invigorating, or even constructing the national community. Although this kind of state respects traditionally liberal concepts like civic rights, it is properly called "illiberal" because it views the community, and not the individual, as the basic political unit.[188] In practice, Orbán claimed, such a state should promote national self-sufficiency, national sovereignty, familialism, full employment and the preservation of cultural heritage, and cited countries such as Turkey, India, Singapore, Russia, and China as models.[188]

Orbán's second and third premierships have been the subject of significant international controversy, and reception of his political views is mixed. The 2011 constitutional changes enacted under his leadership were, in particular, accused of centralizing legislative and executive power, curbing civil liberties, restricting freedom of speech, and weakening the Constitutional Court and judiciary.[189] For these reasons, critics have described him as "irredentist,"[190] "right-wing populist,"[191] "authoritarian,"[192] " far-right",[193] autocratic,"[194] "Putinist,"[195] as a "strongman,"[196] and as a "dictator."[197]

Other commentators, however, noted that the European migrant crisis, coupled with continued Islamist terrorism in the European Union, have popularized Orbán's nationalist, protectionist policies among European conservative leaders. "Once ostracized" by Europe's political elite, writes Politico, Orbán "is now the talisman of Europe's mainstream right."[181] As other Visegrád Group leaders, Orbán opposes any compulsory EU long-term quota on redistribution of migrants.[198]

He wrote in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: "Europe's response is madness. We must acknowledge that the European Union's misguided immigration policy is responsible for this situation."[199] He also demanded an official EU list of "safe countries" to which migrants can be returned.[200] According to Orbán, Turkey should be considered a safe third country.[201]

As mentioned above, Orbán has promoted the Great Replacement conspiracy theory. In a 2018 speech, he stated: "I think there are many people who would like to see the end of Christian Europe, and they believe that if they replace its cultural subsoil, if they bring in millions of people from new ethnic groups which are not rooted in Christian culture, then they will transform Europe according to their conception."[202]

During a press conference in January 2019, Orbán praised Brazil's president Jair Bolsonaro, saying that currently "the most apt definition of modern Christian democracy can be found in Brazil, not in Europe."[203]

In support of Orbán and his ideas, a think tank called the Danube Institute was established in 2013, funded by the Batthyány Foundation, which in turn is "funded entirely by the Hungarian government".[204] Batthyány "sponsors international conferences and three periodicals, all in English: European Conservative, Hungarian Review, and Hungarian Conservative". In 2020, the institute began hosting fellows.[204]

- In the United States

Orbán often attacked the administrations of presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden, particularly for their supposed pro-immigration policies. Some analysts argue that Orban's attacks on the US are largely political theater for his domestic voters.[22]

In January 2022, Donald Trump endorsed Orbán in the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary election, saying in a statement that he “truly loves his Country and wants safety for his people,” and praising his hard-line immigration policies.[205][206] Donald Trump's former chief strategist, Steve Bannon, once called Orbán "Trump before Trump."[162]

In August 2021, Tucker Carlson hosted some episodes of his show, Tucker Carlson Tonight, from Budapest, praising Orbán as the one elected leader "on the face of the earth, ... who publicly identifies as a Western-style conservative". He also conducted a fifteen-minute interview with Orbán, which was widely criticized for its fawning nature and lack of challenging questions.[204]

In May 2022 the Conservative Political Action Conference, the "flagship conference" of American conservatism,[184] held a satellite event in Budapest.[207] In Florida, a law regulating sex education in schools, sometimes called the “Don’t Say Gay” law, resembles a similar Hungarian law passed in 2021 and was, according to governor Ron DeSantis's press secretary, inspired by it.[204]

In August 2022, Orbán was the opening speaker at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Dallas, Texas.[208]

Domestic policy

Viktor Orbán's domestic policy agenda has placed emphasis on cultural conservatism, especially through pro-natalist policies designed to encourage family formation and reduce immigration. Female university graduates who have (or adopt) children within two years of graduation receive partial or full forgiveness on their student loans, including a full write-off of their student debt if they have three or more children.[209][210] Hungarian women who have four or more children are eligible for full income tax exemption for life.[211] Married couples are eligible for low fixed-rate mortgages on a house with additional financial support through family housing benefits, as well as subsidies for the purchase of seven-seat cars for families with three or more children and financial support for child care.[212] In support of these policies, Orbán stated in 2019 that "For the west, the answer is immigration. For every missing child there should be one coming in and then the numbers will be fine. But we do not need numbers. We need Hungarian children."[213] The government has also tightened legal regulations on access to abortion, including requiring pregnant women to listen to the heartbeat of the fetus prior to an abortion being approved by a doctor.[214] The number of abortions procured in Hungary between 2010 and 2021 fell almost 50%, from 34 per hundred live births in 2010 to 23.7 per hundred in 2021.[215]

His government's economic approach has been referred to as "Orbánomics".[216] Despite early concerns that these reforms would undermine investor confidence, economic growth has been strong with unemployment "plummeting" between 2010 and 2021 and year-on-year GDP growth at 4 percent in 2021.[217] Progressive taxation on income was abolished in 2015 and replaced with a flat rate of 16% on gross income, and income taxes on those aged 25 years or younger was abolished entirely in 2021.[218] Hungary paid the last of its IMF loan ahead of schedule in 2013, with the fund closing its Budapest office later that year.[219] Due to the economic impact of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, as well as the shocks of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, Orbán's government has imposed windfall taxes on banks, pharmaceutical companies, and energy companies in order to maintain a government-subsidized cap on utility bills (including gas, electricity, water, district heating, sewage, and garbage collection) which continues into 2023.[220]

Orbán's government has encouraged and provided financial support for the establishment of conservative think-tanks and cultural institutions. The Mathias Corvinus Collegium has purchased stakes in several European universities and has purchased the Modul University in Vienna.[221][222] The Collegium process begins at elementary school and continues up to graduate-level education. After identifying the 10,000 most talented Hungarian students, the top students are recruited into after-school programs in over 35 cities which include tutoring in English, civics education, and extracurricular opportunities. It has also purchased and renovated hotels across Hungary into student accommodation, offered for free for enrolled students, as well as post-graduation work and networking opportunities.[223] The thinktank's Brussels branch opened in November 2022.[224] In 2021, Orbán's government passed a bill which privatized 11 Hungarian universities and subsequently were endowed billions of euros in assets from the state budget, as well as real estate and shares in large companies. The government has appointed conservatives to the supervisory boards of these universities.[225]

As part of a drive to "re-Christianize" the country, his government has privatised many previously state-run schools and enlisted Christian churches to provide education, introduced religion classes into the national education curriculum, and provided financial support to more Christian schools.[226] The country's kindergarten curriculum was amended to promote "national identity, Christian cultural values, patriotism, attachment to homeland and family".[227] Between 2010 and 2018, the number of Catholic schools increased from 9.4 percent to 18 percent.[228] The government also created the Center for Fundamental Rights (Hungarian: Alapjogokért Központ) in 2013 who describe their mission as "preserving national identity, sovereignty and Christian social traditions".[227] In 2019 the government passed a law taking control of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[229]

انتقاد سياساته وأساليبه

من الداخل

Bálint Magyar , former Minister of Education, published his book in 2013, Magyar polip – A post-communist mafia state , wrote about how the country has developed into a mafia state, which is controlled by Orbán's political-economic clan. The two-thirds victory opened the way for Orbán to dismantle the democratic system and institutionalize the autocrat's political position.

من الخارج

Orbán's critics have included domestic and foreign leaders (including former United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton,[230] German Chancellor Angela Merkel,[231] and the Presidents of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso,[232] and Jean-Claude Juncker),[233] intergovernmental organizations, and non-governmental organizations. He has been accused of pursuing anti-democratic reforms; attacking the human rights of the LGBT community; reducing the independence of Hungary's press, judiciary and central bank; amending Hungary's constitution to prevent amendments to Fidesz-backed legislation; and of cronyism and nepotism.[234][235][236]

Pork barrel spending

He was accused of pork barrel politics for building Pancho Aréna, a 4,000-seat stadium in the village in which he grew up, Felcsút,[237] at a distance of some 6 metres (20 ft) from his country house.[237]

Economic cronyism

In the book The Ark of Orbán, Attila Antal wrote that the Orbán system of governance is characterized by the transformation of public money into private money, a system that has built a neo-feudal world of national capitalists, centered on the prime minister and his own family business interests. The largest share of national capitalists is the oligarchy “produced” by the system, such as István Tiborcz, who is closest to Viktor Orbán, and Lőrinc Mészáros and his family.[238]

A 2016 opinion piece for The New York Times by Kenneth Krushel called Orbán's political system a kleptocracy that wipes some of the country's wealth partly into its own pockets and partly into the pockets of people close to it.[239]

A 2017 Financial Times article compared the Hungarian elite under Orbán's government to Russian oligarchs. The article noted that they differ in that Hungary's "Oligarchs" under Orbán largely benefit from EU subsidies, unlike the Russian oligarchs. The article also mentioned the sudden increase in the personal wealth of Orbán's childhood friend, Lőrinc Mészáros, thanks to winning state contracts.[240]

A 2019 New York Times investigation revealed how Orbán leased plots of farm land to politically connected individuals and supporters of his and his party, thereby channeling disproportionate amounts of the EU's agricultural subsidies Hungary receives every year into the pockets of cronies.[241]

Opposition to European integration

Some opposition parties and critics also consider Orbán an opponent of European integration. In 2000, opposition parties MSZP and SZDSZ and the left-wing press presented Orbán's comment that "there's life outside the EU" as proof of his anti-Europeanism and sympathies with the radical right.[242][243] In the same press conference, Orbán clarified that “It will not be a tragedy if we cannot join the EU in 2003. (...) But this is not what we are preparing for. We are trying to urge our integration [into the EU], because it may give a new push to the economy.”[244]

Migrant crisis

Hungarian-American business magnate and political activist George Soros criticized Orbán's handling of the European migrant crisis in 2015, saying: "His plan treats the protection of national borders as the objective and the refugees as an obstacle. Our plan treats the protection of refugees as the objective and national borders as the obstacle."[245]

Orbán has been criticized for engineering the 2015 European migrant crisis for his own political gain. Specifically, he has been accused of mistreating migrants within Hungary and later sending many to Western Europe in an effort to stoke far-right sympathies in Western European countries.[246][247] During the crisis, Orbán ordered fences be put up across the Hungarian borders with Serbia and Croatia and refused to comply with the European Union's mandatory asylum quota.[248]

In 2015, The New York Times acknowledged that Orbán's stance on migration is slowly becoming mainstream in European politics. Andrew Higgins interviewed Orbán's ardent critic, György Konrád, who said that Orbán was right and Merkel was wrong concerning the handling of the migrant crisis.[249]

- Anti-Soros theme

The Orbán government began to attack George Soros and his NGOs in early 2017, particularly for his support for more open immigration. In July 2017, the Israeli ambassador in Hungary joined Jewish groups and others in denouncing a billboard campaign backed by the government. Orbán's critics claimed it "evokes memories of the Nazi posters during the Second World War". The ambassador stated that the campaign "evokes sad memories but also sows hatred and fear", an apparent reference to the Holocaust. Hours later, Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a "clarification", denouncing Soros, stating that he "continuously undermines Israel's democratically elected governments" and funded organizations "that defame the Jewish state and seek to deny it the right to defend itself". The clarification came a few days before an official visit to Hungary by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.[250] The anti-Soros messages became key elements of the government's communication and campaign since then, which, among others, also targeted the Central European University (CEU).[251][252][253][254]

Journalist Andrew Marantz argues that whether or not Soros was doing any actual harm to Hungary or conservative values, it was important to have a face to attack in a political campaign rather than abstract ideas like "globalism, multiculturalism, bureaucracy in Brussels"; and that this was a strategy explained to Orbán by political consultant Arthur J. Finkelstein.[204]

Accusations of antisemitism

Orbán has been frequently accused of antisemitism, particularly for promoting conspiracy theories about the Jewish philanthropist George Soros.[255][256] In 2022 he was condemned by the International Auschwitz Committee for comments in which he criticised mixing "with non-Europeans". The Committee called on the EU to continue to distance itself from "Orbán's racist undertones and to make it clear to the world that a Mr. Orbán has no future in Europe."[257] Others have rejected the claim that he is antisemitic, arguing that his founding of the Holocaust Memorial Center and Memorial Day for the Hungarian Victims of the Holocaust are evidence of this.[258][259] He has also been accused of rehabilitating antisemitic Hungarian historical figures and of exploiting antisemitism.[260][261][262]

Democratic backsliding and authoritarianism

Commentators widely discussed democratic backsliding under Orbán. Following a decade of Fidesz–KDNP rule led by Orbán, Freedom House's Nations in Transit 2020 report reclassified Hungary from a democracy to a transitional or hybrid regime.[263] According to former minister of education, Bálint Magyar, international observers have called elections in Hungary under Orbán "free but not fair",[264] due to manipulation of electoral districts and "undisclosed infusions" of funds for political campaigns. In the April 2022 election, Orbán's Fidesz party won 54% of the vote but 83% of the districts, due to gerrymandering (political manipulation of electoral district boundaries to create undue advantage for a political group), and "other tweaks" to Hungarian electoral rules.[204] Unlike many strongmen, Orbán has not taken advantage of a crisis to amass power or used a coup to come to power but made himself safe from the danger of losing an election slowly, methodically, and legally, with his pro-democracy opposition being compared to the proverbial boiling frog (by Tibor Dessewffy, a sociology professor at Eötvös Loránd University, leading political advisor of former prime minister, Ferenc Gyurcsány).[265]

According to Andrew Marantz, Orbán has passed laws, amended the constitution, and finally written a new constitution, allowing him to do what he wanted to do. Civic institutions such as courts, universities, and the apparatus necessary for free elections remain, but have been "patiently debilitated, delegitimatized, hollowed out", controlled by Orbán loyalists.[204] Domination of the public media by Orbán prevents the public from hearing critics' point of view. In 2022, Orbán's opponent was given just five minutes on the national television "to make his case to the voters".[204] Private media outlets like the ATV and RTL, among others, offered playtime for opposition members. According to Andrew Marantz, an example of the discreet, below-the-radar process of accumulating power by Orbán and his party was the creation of a special police force that started as a small anti-terror unit. The unit grew and became more powerful "bit by bit in disparate clauses buried in unrelated laws". According to Princeton professor, sociologist Kim Lane Scheppele, "I was reading article 61 of a bill on public waterworks, literally, and I came across a line that said oh, by the way, the anti-terror unit now gets to collect personal information on all water utility customers, which basically means everyone in the country, without notifying them." Scheppele contends the unit now has enough power to function "essentially" as Orbán's "secret police".[204] Hungarian political scientist András Körösényi, using Max Weber's classification, argues that Orbán's rule cannot be described simply by the notions of authoritarianisation or illiberalism. He stresses out that the Orbán regime can be characterised as plebiscitary leadership democracy instead.[266][267][268]

Irredentism and nativism

Orban's policy positions have been reported to lean towards irredentism and nativism.[269][270] He has overseen the transfer of hundreds of millions of Hungarian taxpayer money for the preservation of Hungarian language and monuments and institutions of the Hungarian diaspora, particularly in Romania, irking the Romanian government.[271]

Mixed-race statement

In a speech delivered to the 31st Bálványos Free Summer University and Student Camp in July 2022, Orbán expressed views that were later described as "a pure Nazi text" that was "worthy of Goebbels" by one of his senior advisers, Zsuzsa Hegedüs, in her letter of resignation.[19][272] In the speech, Orbán stated that "Migration has split Europe in two – or I could say that it has split the West in two. One half is a world where European and non-European peoples live together. These countries are no longer nations: they are nothing more than a conglomeration of peoples" and "we are willing to mix with one another, but we do not want to become peoples of mixed-race".[273] The speech drew condemnation from both the Romanian foreign ministry and other European leaders.[18] Two days latter, in Wien, Orbán made it clear, he was talking about cultures and not about race. Zsuzsa Hegedüs later, in a letter to Orbán expressed that she is proud of him, and he can count on her like he could in the past 20 years.[274][20]

Later that month, he touched on this criticism in a speech at the CPAC opening in Dallas, saying that "a Christian politician cannot be racist" and calling his critics "simply idiots".[275][207][276] He also attacked billionaire George Soros, former United States President Barack Obama, "globalists," and the United States' Democratic Party.[275]

الحياة الشخصية

Orbán married jurist Anikó Lévai in 1986; the couple has five children.[277] Their eldest daughter, Ráhel, is married to entrepreneur Tiborcz István, whose company, Elios, was accused of receiving unfair advantages when winning public tenders.[278] (see Elios case) Orbán's son, Gáspár, is a retired footballer, who played for Ferenc Puskás Football Academy in 2014.[279] Gáspár is also one of the founders of a religious community called Felház.[280] Orbán has three younger daughters (Sára, Róza, Flóra) and three granddaughters (Ráhel's children Aliz and Anna Adél; Sára's daughter Johanna).

Orbán is a member of the Calvinist-oriented Hungarian Reformed Church, while his wife and their five children were raised Catholic.[281] His son Gáspár Orbán converted in 2014 to the Faith Church, a Pentecostal denomination, and is currently a minister who claims to have heard from God and witnessed miraculous healings.[282]

Football interests

Orbán is very fond of sports, especially of football; he was a signed player of FC Felcsút, and as a result he also appears in Football Manager 2006.[283][284]

Orbán has played football from his early childhood. He was a professional player with FC Felcsút. After ending his football career, he became one of the main financiers of the Hungarian football and his hometown's club, Felcsút FC, later renamed the Ferenc Puskás Football Academy.[285] He had a prominent role in the foundation of Puskás Akadémia in Felcsút, creating one of the most modern training facilities for young Hungarian footballers.[286]

He played an important role in establishing the annually organised international youth cup, the Puskás Cup, at Pancho Aréna, which he also helped build,[287][288] in his hometown of Felcsút. His only son, Gáspár, learned and trained there.[289]

Orbán is said to watch as many as six games a day. His first trip abroad as prime minister in 1998 was to the World Cup final in Paris; according to inside sources, he has not missed a World Cup or Champions League final since.[284]

Then FIFA president Sepp Blatter visited the facilities at the Puskás Academy in 2009. Blatter, together with the widow of Ferenc Puskás, as well as Orbán, founder of the academy, announced the creation of the new FIFA Puskás Award during that visit.[290] He played the minor role of a footballer in the Hungarian family film Szegény Dzsoni és Árnika (1983).[291]

انظر أيضاً

- First Orbán Government

- Second Orbán Government

- Third Orbán Government

- Fourth Orbán Government

- Fifth Orbán Government

- Orbanomics

- List of prime ministers of Hungary by tenure

العمل السياسي

رئاسة الوزراء الثانية 2010

جدل

متفرقات

كتب نشرت بالمجرية

- Hollós, János – Kondor, Katalin: Szerda reggel – Rádiós beszélgetések Orbán Viktor miniszterelnökkel, 1998. szeptember – 2000. december, ISBN 963-933-732-3

- Hollós, János – Kondor, Katalin: Szerda reggel – Rádiós beszélgetések Orbán Viktor miniszterelnökkel, 2001–2002, ISBN 963-933-761-7

- A történelem főutcáján – Magyarország 1998–2002, Orbán Viktor miniszterelnök beszédei és beszédrészletei, Magyar Egyetemi Kiadó, ISBN 963-863-831-1

- 20 év – Beszédek, írások, interjúk, 1986–2006, Heti Válasz Kiadó, ISBN 963-946-122-9

- Egy az ország. Helikon Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 2007. (translated into Polish as Ojczyzna jest jedna in 2009)[292]

- Rengéshullámok. Helikon Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 2010.[293]

المصادر

الهوامش

- ^ Orbánnak kiütötték az első két fogát, Origo, 20 December 2012; accessed 30 August 2012

- ^ Szurovecz, Illés (30 November 2020). "Varga Judittól kellett megtudnunk, hogy Orbán Viktor többet volt hatalmon, mint bármelyik magyar miniszterelnök a történelemben". 444.hu (in الهنغارية). Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "What to do when Viktor Orbán erodes democracy". The Economist. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ أ ب Kingsley, Patrick (10 February 2018). "As West Fears the Rise of Autocrats, Hungary Shows What's Possible". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Maerz, Seraphine F.; Lührmann, Anna; Hellmeier, Sebastian; Grahn, Sandra; Lindberg, Staffan I. (2020). "State of the world 2019: autocratization surges – resistance grows". Democratization. 27 (6): 909–927. doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1758670. ISSN 1351-0347.

- ^ "The EU is tolerating—and enabling—authoritarian kleptocracy in Hungary". The Economist. 5 April 2018. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Viktor Orban". Encyclopædia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ "World Press Freedom Index 2010". RSF (in الإنجليزية). 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "2020 World Press Freedom Index | Reporters Without Borders". RSF (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Democracy Index 2010: democracy in retreat" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Democracy Index 2020: In sickness and in health?". Economist Intelligence Unit. 2020.

- ^ Kelemen, R. Daniel (8 February 2019). "Hungary's democracy just got a failing grade". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, Nazifa Alizada, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Allen Hicken, Garry Hindle, Nina Ilchenko, Joshua Krusell, Anna Lührmann, Seraphine F. Maerz, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Josefine Pernes, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2021. "V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v11.1" Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds21.

- ^ "Full text of Viktor Orbán's speech at Băile Tuşnad (Tusnádfürdő) of 26 July 2014". The Budapest Beacon. 30 July 2014.

- ^ "Hungarian PM sees shift to illiberal Christian democracy in 2019 European vote". Reuters. 28 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban said on Saturday that European parliament elections next year could bring about a shift toward illiberal 'Christian democracy' in the European Union that would end the era of multiculturalism.

- ^ "Hungary Orban: Europe's centre-right EPP suspends Fidesz". BBC. 20 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Hungary: Viktor Orban's ruling Fidesz party quits European People's Party". Deutsche Welle. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Viktor Orbán adviser resigns after Hungarian premier's 'mixed race' speech". Financial Times. 2022-07-27. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ^ أ ب "'Nazi' talk: Orbán adviser trashes 'mixed race' speech in dramatic exit". POLITICO (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ^ أ ب ت "Hegedüs Zsuzsa szerint Orbán Bécsben "korrigált", ő azonban távozik a posztjáról". Szabadeuropa (in الهنغارية). Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Kelemen, R. Daniel (2017). "Europe's Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe's Democratic Union". Government and Opposition (in الإنجليزية). 52 (2): 211–238. doi:10.1017/gov.2016.41. ISSN 0017-257X.

- ^ أ ب Buyon, Noah (6 December 2016). "Orban and Trump Want Closer Ties, But Politics Could Get in the Way". Foreign Policy (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Roth-Rowland, Natasha (7 September 2022). "How the antisemitic far right fell for Israel". +972 Magazine.

- ^ A Közgép is hizlalhatja Orbán Győző cégét, Heti Világgazdaság, 11 July 2012.

- ^ "Erzsébet Sípos". Geni.com. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Lendvai 2017, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Pünkösti, Árpád (13 May 2000). "Szeplőtelen fogantatás 7". Népszabadság (in الهنغارية). Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ أ ب (in hu)Orbán Viktor, Hungary: arlament, 1996, http://www.parlament.hu/kepviselo/elet/o320.htm

- ^ Lendvai 2017, pp. 14, 265.

- ^ Pünkösti Árpád: Szeplőtelen fogantatás. Népszabadság Könyvek, Budapest, 2005, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Debreczeni, József (2002) (in hu), Orbán Viktor, Budapest: Osiris

- ^ أ ب Kenney, Padraic (2002). A Carnival of Revolution: Central Europe 1989. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-691-05028-7.

- ^ Debreczeni, József: Orbán Viktor, Osiris Kiadó, Budapest, 2002.

- ^ Faculty of Law - website of Eötvös Loránd University

- ^ Curriculum vitae of Viktor Orbán - website of the Hungarian government

- ^ Dr. Orbán Viktor - website of the Hungarian parliament

- ^ (in hu)Orbán Viktor, Hungary: National Assembly, http://www.parlament.hu/kepv/eletrajz/hu/o320.pdf

- ^ Fulbright report, Oxford, United Kingdom, http://www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk/files/Fulbright_report.pdf

- ^ Lendvai 2017, p. 23.

- ^ Lendvai 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Lendvai 2017, pp. 17–21.

- ^ Schwartzburg, Rosa; Szijarto, Imre (24 July 2019). "When Orbán Was a Liberal". Jacobin. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ LeBor, Adam (11 September 2015). "How Hungary's Prime Minister Turned From Young Liberal Into Refugee-Bashing Autocrat". The Intercept. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Martens 2009, pp. 192–193.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Register". Országgyűlés.

- ^ "Hungary under Orbán: Can Central Planning Revive Its Economy?, Simeon Djankov, Peterson Institute for International Economics, July 2015; accessed 20 January 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Petőcz, György: Csak a narancs volt. Irodalom Kft, 2001 ISBN 963-00-8876-2.

- ^ أ ب Vida, István (2011). Magyarországi politikai pártok lexikona (1846–2010) [Encyclopedia of the Political Parties in Hungary (1846–2010)] (in الهنغارية). Gondolat Kiadó. pp. 346–350. ISBN 978-963-693-276-3.

- ^ Orbán Viktor életrajza, Government of Hungary, accessed 4 April 2020

- ^ Lendvai 2017, p. 26.

- ^ أ ب Martens 2009, p. 193.

- ^ Kormányfői múltidézés: a jogászok a nyerők, Zona.hu.

- ^ "Stumpf lesz a miniszterelnök-helyettes". Origo (in الهنغارية). 21 November 2001. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ István Kukorelli – Péter Smuk: A Magyar Országgyűlés 1990–2010. Országgyűlés Hivatala, Budapest, 2011. pp. 47–48.

- ^ "A parlamenti pártokat még mindig megosztja a háromhetes ülésezés". Népszava. 3 March 2000.

- ^ "Bírálják az új munkarendet. A háromhetes ciklus miatt összeomolhat a törvénygyártás gépezete". Népszava. 4 March 1999.

- ^ Bodnár, Lajos (23 July 2001). "Marad a háromhetes munkarend. Az ellenzéknek az őszi parlamenti ülésszak idején sem lesz ereje a változtatáshoz". Magyar Hírlap.

- ^ Tamás Bauer: A parlament megcsonkítása. Népszava, 8 February 1999.

- ^ 4/1999. (III. 31.) AB határozat[dead link], Magyar Közlöny: 1999. évi 27. szám and AB közlöny: VIII. évf. 3. szám.

- ^ Orbán nem gyanít korrupciót a Lockheed-botrány mögött, Origo, 26 May 1999; accessed 24 July 2012.

- ^ Történeti áttekintés Archived 13 سبتمبر 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Theatre; accessed 17 June 2018. (in مجرية).

- ^ Népszabadság Archívum, Népszabadság; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ "Nemzetközi Újságíró-szövetség vizsgálná a magyar médiát". Index (in الهنغارية). 13 January 2001. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ Torgyán lemondott, Index, 8 February 2001; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ أ ب Gazdag, László: Így kormányozták a magyar gazdaságot Archived 4 يوليو 2015 at the Wayback Machine, FN.hu, 12 February 2012; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ Magyarország teljes jogú NATO-tag, Origo, 12 March 1999; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ Bell 2003, p. 315.

- ^ Michael Toomey, "History, nationalism and democracy: myth and narrative in Viktor Orbán's ‘illiberal Hungary’." New Perspectives. Interdisciplinary Journal of Central & East European Politics and International Relations 26.1 (2018): 87-108 [1][dead link].

- ^ Nastase-Orbán egyezség készül a státustörvényről, Transindex, 17 December 2001; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ A magyar státustörvény fogadtatása és alkalmazása a Szlovák Köztársaságban Archived 4 مارس 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Legal Analyses-Kalligram Foundation; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ Gallup: nőtt a Fidesz-MDF közös lista előnye, Origo, 15 November 2001; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p. 899 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ^ A MIÉP cselekvésre szólít a 'csalás' miatt, Index, 22 April 2002; accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ Hack, Péter (18 June 2004). "A vereség tanulságai". Hetek (in الهنغارية). Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "A Fidesz győzött, és a legnagyobb európai frakció tagja lesz". 24.hu (in الهنغارية). 14 June 2004. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ (in hu)Országos Választási Iroda – 2006 Országgyűlési Választások eredményei, Valasztas, http://www.valasztas.hu/parval2006/main_hu.html

- ^ Ismét Orbán Viktor lett a Fidesz elnöke Archived 25 مارس 2012 at the Wayback Machine Politaktika.hu; accessed 12 April 2018.

- ^ Gorondi, Pablo (27 February 2007) "Hungary's prime minister expects political tension but no riots on 15 March commemorations", Associated Press.

- ^ "Vokscentrum – a választások univerzuma". Vokscentrum.hu. 2006. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Opposition makes substantial gains in Hungarian elections". Taipei Times. 3 October 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Hungarian president announces referendum date", Xinhua (People's Daily), 24 January 2008.

- ^ "Hungary's ruling MSZP vows to stick to medical reforms despite referendum – People's Daily Online". People's Daily. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Edelényi, Márk; Tóth, András; Neumann, László (18 May 2008). "Majority vote 'yes' in referendum to abolish medical and higher education fees". European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "EP-választás: A jobboldal diadalmenete". EURACTIV. 8 June 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Q&A Hungary's controversial constitutional changes". BBC News. 11 March 2013.

- ^ Dempsey, Judy (18 April 2011). "Hungarian Parliament Approves New Constitution". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Hungarian lawmakers approve socially and fiscally conservative new constitution", The Washington Post, 18 April 2011; accessed 25 April 2011

- ^ Margit Feher, "Hungary Passes New Constitution Amid Concerns", The Wall Street Journal, 18 April 2011; accessed 26 April 2011

- ^ "Hungarian president signs new constitution despite human rights concerns", Deutsche Welle, 25 April 2011; accessed 25 April 2011

- ^ "New electoral system in the home stretch" (PDF). Valasztasirendszer.

- ^ "Hungary's parliament passes controversial new constitution". Deutsche Welle. 18 April 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Lyman, Rick; Smale, Alison (7 November 2014). "Defying Soviets, Then Pulling Hungary to Putin". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Opposing Orban". The Economist. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Eder, Marton. "Hungary's personal income tax still under fire. The Wall Street Journal. June 2012.

- ^ "Hungary PM Viktor Orban: Antagonising Europe since 2010". BBC News. 4 September 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Hungary election: PM Viktor Orban declares victory". BBC News. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Troianovski, Anton (19 August 2015). "Migration crisis pits EU's East against West". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Savitsky, Shane (1 February 2017). "Border fences and refugee bans: Hungary did it — fast". Axios. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Dunai, Marton; Komuves, Anita (21 May 2020). "Hungary tightens asylum rules as it ends migrant detention zones". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Than, Krisztina; Szakacs, Gergely (9 April 2018). "Hungary's Strongman Viktor Orban Wins Third Term in Power". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ Zalan, Eszter (9 April 2018). "Hungary's Orban in Sweeping Victory, Boosting EU Populists". EUobserver. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ Murphy, Peter; Khera, Jastinder (9 April 2018). "Hungary's Orban Claims Victory as Nationalist Party Takes Sweeping Poll Lead". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Hungary passes law allowing Viktor Orban to rule by decree". Deutsche Welle. 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020.

- ^ Bayer, Lili (30 March 2020). "Hungary's Viktor Orbán wins vote to rule by decree". Politico. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Silvia Amaro (31 March 2020). "Coronavirus in Hungary – Viktor Orban rules by decree indefinitely". Cnbc.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Megszűnt a veszélyhelyzet, de életbe lépett a járványügyi készültség". koronavirus.gov.hu (in الهنغارية). 18 June 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Skorić, Toni (29 June 2020). "Is the State of Emergency in Hungary Really Over?". Friedrich Naumann Stiftung für die Freiheit (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Lehotai, Orsolya (17 July 2020). "Hungary's Democracy Is Still Under Threat". Foreign Policy (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Novak, Benjamin (28 April 2021). "Hungary Transfers 11 Universities to Foundations Led by Orban Allies". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ "Hungary's Orban extends dominance through university reform". Reuters. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Hopkins, Valerie (28 June 2021). "Campus in Hungary is Flagship of Orban's Bid to Create a Conservative Elite". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ "The Green Brief: East-West EU split again over climate". Euractiv. 20 October 2021.

- ^ أ ب Komuves, Anita; Szakacs, Gergely (3 April 2022). "Orban on track for crushing victory as Ukraine war solidifies support". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت Amaro, Silvia (2 March 2022). "Putin loses his key ally in the EU as Hungary's Orban turns on the Russian leader". CNBC (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (19 May 2020). "Hungary votes to end legal recognition of trans people". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Nattrass, William (11 June 2021). "Orbán's LGBT+ crackdown extends to schools". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Strozewski, Zoe (23 June 2021). "Angela Merkel Joins Other EU Leaders in Criticizing Hungary's LGBT Law: 'This Law is Wrong'". Newsweek. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (24 June 2021). "EU leaders to confront Hungary's Viktor Orbán over LGBTQ+ rights". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Chastand, Jean-Baptiste; Stroobants, Jean-Pierre (2 December 2020). "Jozsef Szajer, eurodéputé du parti de Viktor Orban, démissionne après une soirée de débauche sexuelle en plein confinement". Le Monde (in الفرنسية). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (2 December 2020). "Hungary's rightwing rulers downplay MEP 'gay orgy' scandal amid hypocrisy accusations". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Berretta, Emmanuel (4 December 2020). "Hongrie : Viktor Orban gêné par les frasques du député Jozsef Szajer". Le Point (in الفرنسية). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Wrong Direction on Rights". Human Rights Watch (in الإنجليزية). 16 May 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2021.