رون ديسانتيس

رون ديسانتس | |

|---|---|

ديسانتس عام 2021 | |

| حاكم فلوريدا رقم 46 | |

| تولى المنصب 8 يناير 2019 | |

| النائب | جانيت نونيز |

| سبقه | ريك سكوت |

| عضو of the U.S. مجلس النواب عن فلوريدا's 6th district | |

| في المنصب 3 يناير 2013 – 10 سبتمبر 2018 | |

| سبقه | كليف ستيرنز |

| خلـَفه | مايكل والتز |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | دونال ديون ديسانتس 14 سبتمبر 1978 جاكسونڤل، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة |

| الحزب | الجمهوري |

| الزوج | |

| الأنجال | 3 |

| الإقامة | منزل الحاكم |

| التعليم |

|

| التوقيع |  |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | Official website |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الولاء | |

| الفرع/الخدمة | |

| سنوات الخدمة | 2004–2019[1][2] |

| الرتبة | رائد بحري |

| الوحدة | Judge Advocate General's Corps احتياطي البحرية الأمريكية |

| المعارك/الحروب | حرب العراق |

| الأوسمة | النجمة البرونزية وسام تكريم سلاح البحرية والبحرية وسام خدمة الحرب العالمية على الإرهاب وسام حرب العراق |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

مجلس النواب الأمريكي

حاكم فلوريدا

|

||

دونالد ديون دىسانتيس/ديسانتيس (إنگليزية: Ronald Dion DeSantis، /dəˈsæntɪs/ أو /diːsæntɪs/؛[3] و. 14 سبتمبر 1978)، هو سياسي أمريكي وحاكم فلوريدا رقم 46 منذ 2019. كعضو في الحزب الجمهوري، مثل ديسانتيس دائرة فلوريدا السادسة في مجلس النواب الأمريكي من 2013 حتى 2018.

وُلد ديسانتيس في جاكسونڤل، فلوريدا وقضى معظم سنوات طفولته في دوندين. تخرج من جامعة يل وكلية حقوق هارڤرد. انضم ديسانتس إلى البحرية الأمريكية عام 2004 ورُقي لرتبة ملازم قبل بدء خدمته كمستشار قانوني بالقوات الخاصة البحرية الأولى. عام 2006 كان متمركزاً في قوة المهام المشتركة في جوانتنامو، وكُلف بالخدمة في العراق عام 2007. عند عودته للولايات المتحدة بعد حوالي ثمانية أشهر، عينته وزارة العدل الأمريكية للخدمة مساعداً خاصاً للمدعي العام الأمريكي في مكتب المدعي العام في المقاطعة الوسطى بفلوريدا، المنصب الذي تقلده حتى تسريحه من الخدمة العسكرية النشطة عام 2010.

انتخب ديسانتيس لعضوية مجلس النواب لأول مرة عام 2012 وأعيد انتخابه عامي 2014 و2016. خلال فترة ولايته أصبح عضوًا مؤسسًا في تجمع الحرية وكان حليفًا للرئيس دونالد ترمپ. انتقد ديسانتيس تحقيق المجلس الخاص روبرت مولر حول مزاعم بوجود "صلات و/أو تنسيق" بين حملة ترمپ والتدخل الروسي في الانتخابات الرئاسية الأمريكية 2016. ترشح ديسانتيس لفترة وجيزة في انتخابات مجلس الشيوخ عام 2016، لكنه انسحب عندما سعى السناتور الحالي ماركو روبيو لإعادة الانتخاب. فاز ديسانتيس بترشيح الحزب الجمهوري في انتخابات حكام الولايات 2018 وهزم بفارق ضئيل المرشح الديمقراطي، ورئيس بلدية تالاهاسي، أندرو جيلوم، في الانتخابات العامة بنسبة 0.4٪.

بصفته حاكمًا قاوم ديسانتس اتخاذ العديد من الإجراءات لإبطاء انتشار كوڤيد-19 التي نفذتها مختلف حكومات الولايات الأخرى، مثل تفويضات أقنعة الوجه، أوامر البقاء في المنزل، ومتطلبات التطعيم. ظل معدل الوفيات بسبب كوڤيد-19 المعدل حسب العمر في ولاية فلوريدا قريباً من المتوسط الوطني، بينما شهدت الولاية نموًا اقتصاديًا أعلى من المتوسط وأسرع نمو سكاني في أي ولاية في البلاد. في مايو 2021، وقع ديسانتيس على مشروع قانون يحظر على الشركات والمدارس وسفن الرحلات البحرية والهيئات الحكومية المطالبة بإثبات التطعيم.

بعد إعادة انتخابه الناجحة كحاكم، كانت هناك تكهنات بأن ديسانتيس سيرشح نفسه لمنصب الرئيس في الانتخابات الرئاسية الأمريكية 2024. أعلن ديسانتيس عن عرضه لمنصب الرئيس في 24 مايو 2023، ويستمر في العمل كحاكم أثناء حملته الانتخابية. ألف كتابين، أحدهما نُشر في 2011 قبل حملته الأولى للكونجرس، والآخر في 2023 قبل حملته الرئاسية.

السنوات المبكرة والتعليم

وُلد ديسانتيس في 14 سبتمبر 1978 في جاكسونڤل، فلوريدا، ابناً لكارن ديسانتيس (لقبها قبل الزواج روجرز) ودونالد دانييل ديسانتيس. اسمه الأوسط، ديون، على اسم المغني ديون ديموتشي.[4] اسم عائلة والدته، روجرز، اختاره جدها عند هجرته من إيطاليا.[5][6][7]

وُلد جميع أجداد-أجداده في جنوب إيطاليا،[nb 1] وهاجروا إلى الولايات المتحدة أثناء الشتات الإيطالي.[13] وُلد ونشأ والديه وجديه في غرب پنسيلڤانيا وشمال شرق أوهايو.[4]

كانت والدة ديسانتوس تعمل ممرضة وكان والده يقوم بتركيب صناديق تصنيفات نلسن.[14] التقيا أثناء دراستهما في جامعة يونجستاون الولائية في ينگستاون، أوهايو، خلال السبعينيات وانتقلا إلى جاكسونڤل، فلوريدا، خلال ذلك العقد.[15]

بعد ذلك انتقلت عائلته إلى أورلاندو، فلوريدا، قبل أن ينتقلوا عندما كان في السادسة من عمره إلى مدينة دنيدن في منطقة تامپا باي.[16] شقيقته الوحيدة، أخته الصغرى كريستينا ماري ديسانتس، ولدت في أورلاندو وتوفيت عام 2015 عن عمر يناهز 30 عامًا جراء الانصمام الرئوي.[17][18][19] كان عضوًا في فريق دندين الوطني الذي وصل إلى بطولة العالم الصغرى 1991 في ويليامسبورت، پنسلڤانيا.[20][21] التحق ديسانتيس بمدرسة أور ليدي أوف لوردز الكاثوليكية ومدرسة دندين الثانوية، حيث تخرج عام 1997.[14]

بعد دراسته الثانوية، درس ديسانتيس التاريخ في جامعة يل. كان كابتن فريق البيسبول بالجامعة، وانضم إلى أخوية دلتا كاپا إپسيلون.[21][22] كان ديسانتس لاعب الدفاع بالفريق؛ بصفته أحد البارزين عام 2001، كان أفضل لاعب في الفريق بمعدل تسديدات 0.336.[23][24][25][26] أثناء دراسته في جامعة يل، عمل في مجموعة متنوعة من الوظائف، بما في ذلك مساعد كهربائي ومدرب في معسكر للبيسبول.[14] تخرج ديسانتس من يل عام 2001 حاصلاً على البكالريوس.[27]

بعد يل، كان يلقي دروس في التاريخ ومدرباً لمدة عام في مدرسة دارلينجتون بجورجيا.[28] بعدها التحق بكلية حقوق هارڤرد، حيث تخرج عام 2005 حاصلاً على دكتوراه القانون .[29][30]

الخدمة العسكرية

عام 2004، خلال سنته الثانية في كلية حقوق هارڤرد، تم تكليف ديسانتيس كضابط في البحرية الأمريكية في فيلق المدعي العام لقاضي البحرية الأمريكية (JAG). أكمل دراسته في مدرسة العدل البحرية عام 2005. في وقت لاحق من ذلك العام، قدم تقريرًا لقيادة مكتب خدمته جنوب شرق في محطة مايپورت البحرية، فلوريدا، كمدع عام. رُقي ديسانتيس إلى ملازم عام 2006.

في ربيع 2006، وصل ديسانتيس إلى قوة المهام المشتركة في جوانتنامو، التي تعمل بشكل مباشر مع المعتقلين في معتقل خليج جوانتنامو.[31][32][33][34] غالبًا ما تُنقح سجلات خدمته في البحرية عند إطلاقها للجمهور، لحماية الخصوصية الشخصية، وفقًا للبحرية.[35] عام 2006 زعم منصور أحمد سعد الضيفي، المحتجز في جوانتنامو، أن ديسانتيس أشرف على الإطعام القسري للمعتقلين.[36][37][38][39][34]

عام 2007، قدم ديسانتيس تقريرًا لمجموعة قيادة الحرب الخاصة البحرية في كورونادو، كاليفورنيا، حيث تم تعيينه كمستشار قانوني القوات الخاصة البحرية الأولى؛ وكُلف بالخدمة في العراق خريف عام 2007 كجزء من عملية زيادة القوات.[40][41] خدم كمستشار خاص لدان ثورليفسون، قائد القوات الخاصة البحرية لقوة مهام العمليات الخاصة-غرب في الفالوجة.[31][32][33]

عاد ديسانتيس إلى الولايات المتحدة في أبريل 2008، وأعيد تعيينه في الخدمة القانونية للمنطقة البحرية الجنوبية الشرقية. عينته وزارة العدل الأمريكية كمساعد خاص للمدعي العام في مكتب المدعي العام بالمنطقة الوسطى بفلوريدا.[40] عمل ديسانتس كمحامي دفاع حتى تسريحه من الخدمة الفعلية في فبراير 2010. وفي الوقت نفسه قُبل في لجنة الاحتياط كملازم في Judge Advocate General's Corps التابع لاحتياطي البحرية الأمريكية.[42]

خلال مسيرته العسكرية، حصل ديسانتيس على وسام النجمة البرونزية، وسام تكريم سلاح البحرية والبحرية، وسام خدمة الحرب العالمية على الإرهاب، ووسام حملة العراق.[31][32][33] ظل يخدم في احتياط البحرية الأمريكية حتى تسلمه منصب الحاكم.[1] انتهت خدمته في البحرية الأمريكية في 12 فبراير 2019، بعد شهر من توليه منصب حاكم فلوريدا، برتبة رائد بحري متقاعد.[1][2]

مجلس النواب الأمريكي (2013–2018)

الانتخابات

هزم ديسانتس ستة مرشحين في الانتخابات التمهيدية للحزب الجمهوري 2012 في منطقة الكونجرس السادسة بفلوريدا،[43] وهزم المرشح الديمقراطي هيذر بيڤن في الانتخابات العامة.[44] أعيد انتخابه عامي 2014[45] و2016.[46]

في مايو 2015، أعلن ديسانتس ترشحه في انتخابات مجلس الشيوخ الأمريكي في فلوريدا 2016. ترشح للمقعد الذي يشغله ماركو روبيو، الذي لم يتقدم في البداية بالترشح لإعادة انتخابه بسبب حملته الرئاسية لعام 2016.[47] DeSantis was endorsed by the fiscally conservative Club for Growth.[48]

عندما أنهى روبيو محاولته الرئاسية وخاض الانتخابات لإعادة انتخابه في مجلس الشيوخ، انسحب ديسانتيس من انتخابات مجلس الشيوخ وخاض الانتخابات لإعادة انتخابه في مجلس النواب.[49]

ولايته في الكونجرس

وقع ديسانتيس على "لا تعهد بضريبة المناخ" ضد أي زيادات ضريبية لمكافحة الاحترار العالمي.[50] وصوت لصالح قانون H.R. 45، الذي كان سيغي قانون الرعاية الميسرة عام 2013.[51] عام 2014 قدم ديسانتيس مشروع قانون كان من شأنه أن يطلب من وزارة العدل تقديم تقرير إلى الكونجرس في أي وقت تمتنع فيه الوكالة الفدرالية عن إنفاذ القوانين.[52][53][54]

عام 2015، كان ديسانتيس عضوًا مؤسسًا في تجمع الحرية، وهي مجموعة من المحافظين والليبرتاريين في الكونجرس. .[33][55][56]

يعارض ديسانتيس تنظيم الأسلحة، وحصل على تصنيف A + من الجمعية الوطنية للبنادق.[57] قال ديسانتيس: "نادرًا ما تؤثر قيود الأسلحة النارية على المجرمين. إنها في الحقيقة تؤثر فقط على المواطنين الملتزمين بالقانون".[58]

كان ديسانتيس منتقدًا لسياسات الهجرة الخاصة بأوباما، بما في ذلك تشريعات الإجراءات المؤجلة (DACA وDAPA)، متهمًا أوباما بالفشل في تنفيذ قوانين الهجرة.[59][60] عام 2015، شارك في رعاية قانون كيت، والذي كان من شأنه أن يزيد العقوبات المفروضة على الأجانب الذين يعودون بشكل غير قانوني إلى الولايات المتحدة بعد إبعادهم.[61] شجع ديسانتيس مفوضي فلوريدا على التعاون مع الحكومة الفدرالية في القضايا المتعلقة بالهجرة.[62]

عام 2016، قدم ديسانتيس قانون الفرص والإصلاح في التعليم العالي، والذي كان سيسمح للولايات بإنشاء أنظمة الاعتماد الخاصة بها. وقال إن هذا التشريع سيمنح الطلاب أيضًا "الوصول إلى أموال القروض الفيدرالية لتخصيصها لفرص تعليمية غير تقليدية، مثل دورات التعلم عبر الإنترنت، والمدارس المهنية، والتلمذة الصناعية في المهن الماهرة".[63]

عام 2016، حصل ديسانتيس على تصنيف "0" من حملة حقوق الإنسان بشأن التشريعات ذات الصلة بحقوق المثليين.[64][65] بعد عامين، صرح ديسانتيس "لصن-سنتشيال" إنه "لا يريد أي تمييز في فلوريدا، أريد أن يتمكن الناس من عيش حياتهم سواء كنت مثلياً أو متديناً".[66]

كان ديسانتيس حاضرًا قبل إطلاق النار في ملعب بيسبول الكونجرس يونيو 2017 ، وسأله الجاني عما إذا كان اللاعبون جمهوريين.[67]

في وقت لاحق من ذلك الصيف، اقترح ديسانتيس تشريعًا كان سينهي بحلول نوفمبر من ذلك العام تمويل تحقيق مولر مع الرئيس ترمپ.[68] قال ديسانتيس أن الأمر الصادر في 17 مايو 2017 الذي بدأ بموجبه التحقيق "لم يحدد جريمة ليتم التحقيق فيها" ومن المرجح أن أنه بداية لرحلة صيد.[69][70]

يدعم ديسانتيس تعديلًا دستوريًا لفرض فترات الولاية لأعضاء الكونجرس، بحيث يقتصر ممثلو الولايات على ثلاث فترات وأعضاء مجلس الشيوخ بفترتين.[71] خدم ديسانتيس ثلاث فترات في مجلس النواب، وتقاعد في 2018 للترشح لمنصب الحاكم.[72]

لجان الكونجرس

أثناء الكونجرس الأمريكي رقم 114، خدم ديسانتيس في لجنة الرقابة والمسائلة، وترأس لجنة الفرعية للأمن القومي.[73] كما خدم في لجنة الشؤون الخارجية، اللجنة القضائية، ولجنة الدراسة للجمهوريين، بالإضافة لعدد من اللجان الفرعية.[74]

السياسة المالية في الكونجرس

قال ديسانتيس إن النقاش حول كيفية تقليل العجز الفدرالي يجب أن يحول التركيز من الزيادات الضريبية إلى تقليص الإنفاق وتحفيز النمو الاقتصادي.[75]

أيد ديسانتيس سياسة "لا ميزانية، لا أجر" للكونجرس لتشجيع تمرير قرار الميزانية.[76] صادق ديسانتيس على قانون REINS، والذي كان سيتطلب أن تخضع اللوائح التي تؤثر بشكل كبير على الاقتصاد لتصويت الكونجرس قبل أن تصبح سارية المفعول.[77] كما أيد فكرة مراجعة نظام الاحتياط الفدرالي.[78]

دعا ديسانتيس إلى استقالة مفوض مصلحة الإيرادات الداخلية جون كوسكينن لأنه "خذل الشعب الأمريكي من خلال إحباط محاولات الكونجرس لتأكيد الحقيقة" حول استهداف مصلحة الإيرادات الداخلية المزعوم للمحافظين.[79][80] شارك في رعاية مشروع قانون لمحاكمة كوسكينن لانتهاك ثقة الشعب.[81] وانتقد موظفة الإيرادات الداخلية لويس ليرنر وطلب منها أن تدلي بشهادتها أمام الكونجرس.[82] عام 2015 صنفت مواطنون ضد نفايات الحكومة، وهي مؤسسة فكرية محافظة، ديسانتيس على أنه "دافع الضرائب الخارق".[83] وهو مؤيد سابق لإلغاء ضريبة الدخل الفيدرالية ومصلحة الدخل، وشارك في رعاية تشريعات لاستبدالها بضريبة مبيعات وطنية تسمى FairTax.[84][85]

عام 2015، اقترح قانون دع السناتورات يعملون، والذي كان من شأنه أن يلغي حافزًا للتقاعد بدلاً من الاستمرار في العمل وكان سيعفي كبار السن من نسبة 12.4 بالمائة من ضريبة رواتب الضمان الاجتماعي؛ كما شارك في رعاية إجراء لإلغاء الضرائب على مزايا الضمان الاجتماعي.[86][87] بحسب پوليتيفاكت ، "نصف صحيح" أن ديسانتيس صوّت لخفض الضمان الاجتماعي والرعاية الطبية وصوت على زيادة سن التقاعد، لأن تلك الأصوات كانت على قرارات غير ملزمة لم تكن لتصبح قانونًا حتى لو تم تمريرها، ولأن الهدف كان تثبيت تلك البرامج الاجتماعية لتجنب المزيد من التخفيضات الحادة في وقت لاحق.[88][89]

رعى ديسانتيس قانون تمكين النقل، والذي كان من شأنه نقل الكثير من المسؤولية عن مشاريع النقل إلى الولايات وتخفيض حاد في ضريبة الغاز الفدرالية.[90][91] عارض ديسانتيس التشريع الذي يطلب من تجار التجزئة عبر الإنترنت تحصيل ودفع ضريبة المبيعات الحكومية.[92] وصوت لصالح قانون خفض الضرائب والوظائف في 2017|قانون خفض الضرائب والوظائف لعام 2017]] ،[93] قائلاً إن مشروع القانون سيؤدي إلى "معدل ضرائب أقل بشكل كبير"، و"إنفاق كامل لاستثمارات رأس المال"، والمزيد من الوظائف لأمريكا.[94]

اختار ديسانتيس عدم تلقي معاش الكونجرس، ورفع إجراء من شأنه إلغاء المعاشات التقاعدية لأعضاء الكونجرس.[78][95] بعد طرح قانون نهاية المعاشات التقاعدية في الكونجرس، قال ديسانتيس: "تصور الآباء المؤسسون المسؤولين المنتخبين كجزء من طبقة الخدم، ومع ذلك تطورت واشنطن إلى ثقافة الطبقة الحاكمة".[96]

حملات انتخابات حاكم فلوريدا

الترشح لمنصب الحاكم 2018

في 5 يناير 2018، تقدم ديسانتيس للترشح لمنصب حاكم فلوريدا لخلافة شاغل الوظيفة الجمهوري ريك سكوت.[97] قبل شهر من الانتخابت كان الرئيس ترمپ قد قال أنه سيدعم ديسانتيس إذا ترشح لمنصب الحاكم.[98]

أثناء الانتخابات التمهيدية للحزب الجمهوري، شدد ديسانتيس على دعمه لترمپ من خلال عرض إعلان يعلّم فيه ديسانتيس أنجاله كيفية "بناء الجدار" ويقول "اجعل أمريكا عظيمة مرة أخرى".[99] وردا على سؤال عما إذا كان يمكنه تحديد قضية اختلف معها مع ترمپ، رفض ديسانتيس الإجابة.[100] في 28 أغسطس 2018، فاز ديسانتيس في الانتخابات التمهيدية للحزب الجمهوري، بعد عزيمته منافسه الرئيسي آدم پونتام.[101]

تضمنت منصة ترشح ديسانتيس دعمًا للتشريعات التي من شأنها أن تسمح للأشخاص الذين يحملون تصاريح أسلحة مخفية حمل الأسلحة النارية علانية.[102] كما أيد قانونًا يفرض استخدام E-Verify من قبل الشركات وحظرًا على مستوى الولاية على المدن الملاذ لحماية المهاجرين غير الشرعيين.[102] وعد ديسانتيس بوقف انتشار المياه الملوثة من بحيرة أوكيشوبي.[102] وأعرب عن دعمه لتعديل دستوري للولاية يتطلب تصويت الأغلبية العظمى لأي زيادات ضريبية.[103]

عارض ديسانتيس السماح للبالغين الأصحاء الذين ليس لديهم أطفال بالحصول على ميديكيد.[103] قال إنه سينفذ برنامجًا طبيًا للقنب، بينما يعارض تقنين القنب الترفيهي.[103][104][105]

في اليوم التالي لفوزه في الانتخابات التمهيدية، في مقابلة تلفزيونية مع فوكس نيوز، قال ديسانتيس، "آخر شيء نحتاج إلى القيام به هو محاولة تبني أجندة اشتراكية مع زيادات ضريبية ضخمة وإفلاس الدولة". حظي استخدامه لكلمة "قرد" باهتمام إعلامي واسع، وفسره البعض، بما في ذلك رئيس الحزب الديمقراطي في فلوريدا تيري ريزو، على أنه صافرة كلب سياسية في إشارة إلى مرشح الحاكم الديمقراطي أندرو جيلوم، وهو أمريكي من أصل أفريقي.[106][107][108][109] أنكر ديسانتيس اتهامه بالعنصرية.[110][111][112][113] كتب دكستر فيلكينز "النيويوركر" عام 2022، واصفاً إياها بأنها "زلة لسان كارثية"، ونقل عن حليف لم يذكر اسمه لديسانتيس، "كنا نتعامل مع جيلوم بقفازات الأطفال لا يمكننا ضرب الرجل لأننا نحاول الدفاع عن حقيقة أننا لسنا عنصريين".[110]

كان يُنظر إلى الانتخابات العامة على أنها "إقصاء".[114] أيد بعض العمداء ديسانتيس، بينما أيد عمداء آخرون جيلوم.[115] حاز ديسانتيس على تأييد رابطة رؤساء الشرطة بفلوريدا.[116] في 5 سبتمبر، أعلن ديسانتيس نائبة الولاية [جانيت نونيز]] نائبة له.[117] في 10 سبتمبر استقال ديسانتيس من مقعده في مجلس النواب للتركيز على حملته الانتخابية.[118]

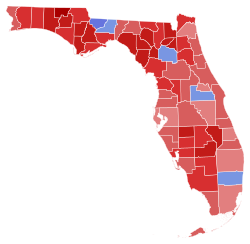

في الشهر نفسه، ألغى مقابلة مخطط لها مع "تامبا باي تايمز" للحصول على وقت إضافي لإنشاء منصة قبل مقابلة سياسية متعمقة.[119] في ليلة الانتخابات، فاز ديسانتيس في النتائج الأولية، ولذا تنازل جيلوم.[120] ألغى جيلوم انسحابه عندما تقلص الهامش إلى 0.4 في المائة، وبدأت عملية إعادة الفرز الآلي في الموعد النهائي في 15 نوفمبر.[121] على الرغم من أن ثلاث مقاطعات تخطت الموعد النهائي، إلا أنه لم يتم تمديدها.[122][123] تم تأكيد أن ديسانتيس هو الفائز وتنازل جيلوم في 17 نوفمبر.[124]

الترشح لمنصب الحاكم 2022

في سبتمبر 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس أنه سيرشح نفسه لإعادة انتخابه.[125] في 7 نوفمبر، قدم الأوراق اللازمة لدخول السباق رسميًا.[126] في الانتخابات العامة، واجه المرشح الديمقراطي تشارلي كريست، ممثل الولايات المتحدة وحاكم فلوريدا السابق.[127] انتقد كريست بشدة قرار ديسانيتس بترحيل المهاجرين غير الشرعيين إلى الدول الديمقراطية، بحجة أن هذا بمثابة انتهاك لحقوق الإنسان.[128] خلال مقابلة مع بريت باير على فوكس نيوز، وصف كريست ديسانتيس بأنه "أحد أكبر التهديدات للديمقراطية".[129]

في 23 أكتوبر عُقدت مناظرة أثناء انتخابات حاكم فلوريدا، وتبادل المرشحون الهجمات. في مرحلة ما، سأل كريست ديسانتيس عما إذا كان سيخدم فترة ولاية كاملة مدتها أربع سنوات، فيما يتعلق بالحديث عن حملة ديسانتيس المحتملة للرئاسة عام 2024. أجاب ديسانتيس، "الحمار القديم البالي الوحيد الذي أتطلع إلى وضعه في المراعي هو تشارلي كريست".[130] أشار ديسانتيس إلى أن كريست قد وعد في حملته الانتخابية 2006 أنه لن يرفع الضرائب، لكن عند انتخابه وقع على زيادة كبيرة في الضرائب والرسوم.[130] كما انتقد دور كريست كعضو في مجلس النواب، قائلاً إنه خلال عام 2022، ظهر كريست في العمل لمدة 14 يومًا فقط.[131]

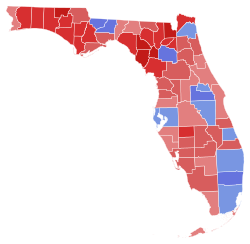

فاز ديسانتيس في انتخابات 8 نوفمبر بأغلبية ساحقة،[132][133][134] بنسبة 59.4 في المائة من الأصوات مقابل كريست 40 في المائة؛ كان أكبر هامش للفوز في انتخابات حاكم ولاية فلوريدا منذ 1982.[135] بشكل ملحوظ، فاز ديسانتيس في مقاطعة ميامي ديد، التي كانت معقلًا ديمقراطيًا منذ 2002، ومقاطعة بالم بيتش، التي لم تصوت للجمهوريين منذ 1986.[136][137] انسحب كريست من الانتخابات بعد فترة وجيزة من التنبؤ بفوز ديسانتيس.[138] في مسيرة فوز ديسانتيس، هتف المؤيدون "عامين آخرين" في أوقات مختلفة بدلاً من "أربع سنوات أخرى" المشتركة لإظهار الدعم لترشح ديسانتيس للرئاسة عام 2024.[139]

حاكم فلوريدا (2019–الحاضر)

أدى افتتح ديسانتيس اليمين أما سكرتير ولاية فلوريدا وأصبح حاكمًا في 8 يناير 2019.[140] أقيمت مراسم أداء اليمين الرسمية ظهر ذلك اليوم. في 11 يناير، أصدر ديسانتيس عفواً عن أربعة جروڤلاند، أربعة رجال سود أدينوا زوراً بالاغتصاب عام 1949.[141][142]

في يناير 2019، علق ديسانتيس رسميًا عمل سكوت إزرائيل شريف مقاطعة بروارد ظاهريًا بسبب ردوده على إطلاق نار جماعي في مطار فورت لودرديل، حيث نزع نائب بروارد سلاح القاتل بعد 85 ثانية من بدء إطلاق النار، ومدرسة مارجوري ستونمان دوجلاس الثانوية، وعين جريجوري توني خلفاً لإزرائيل.[143] في أول أسبوعين له في المنصب، عين ديسانتيس باربرا لاجوا وروبرت جيه لوك وكارلوس جي مونيز في المحكمة العليا في فلوريدا، مغيرًا أغلبية المحكمة من الليبرالية إلى المحافظة. في يناير 2019، وقع على أمر تنفيذي يدعو إلى إنهاء مبادرة المعايير التعليمية الوطنية للصف 12، كمون كور، في فلوريدا.[144][مطلوب مصدر أفضل]

بعد أن سحب المؤتمر الوطني الجمهوري 2020 من المدينة المضيفة التي كانت مقررة في الأصل، شارلوت، في أعقاب الصراع بين ترمپ وحاكم ولاية كارولينا الشمالية روي كوپر حول الخطط الكبرى لتجمع واسع النطاق دون وجود بروتوكولات للصحة العامة لمنع انتشار كوڤيد-19، قام ديسانتيس بحملة لجعل فلوريدا الولاية المضيفة الجديدة.[145]

تنافس مع طلبات مماثلة من تنسي وجورجيا. فاز ديسانتيس، ونُقلت الاحتفالات الرئيسية للمجلس الوطني الجمهوري، بما في ذلك خطاب ترمپ الرئيسي، وانتقل إلى جاكسونڤل.[146][147] في النهاية، ألغيت الفعالية بأكملهت لتتم التجمعات عبر الإنترنت والتلفزيون.[148]

في مايو 2021، وقع صفقة مع قبيلة سمينول بفلوريدا للسماح للقبيلة بتقديم المراهنات الرياضية عبر الإنترنت على مستوى الولاية.[149] في جلستها لعام 2021، أقر مجلس فلوريدا التشريعي أولويات ديسانتيس القصوى.[150][151] خلال فترة ولايته، كان لدى ديسانتيس علاقة سلسة بشكل عام مع المجلس التشريعي، الذي سن العديد من مقترحاته.[152]

نتيجة للزيادة الكبيرة في أسعار الجازولين، في 22 نوفمبر 2021، أعلن ديسانيتس أنه سيتنازل مؤقتًا عن ضريبة الجازولين في فلوريدا في الجلسة التشريعية المقبلة، عام 2022.[153]

في مارس 2023، قال مدققو الحقائق في پوليتيفاكت إنه سيكون من المضلل ومن الخطأ في الغالب القول في المضارع أن ديسانتيس يريد رفع سن التقاعد إلى 70 سنة، لأنه تراجع عن هذا الموقف الذي كان يتخذه قبل عشر سنوات. موقفه الحالي هو أننا "لن نعبث بالضمان الاجتماعي بصفتنا جمهوريين".[89][154][88]

كوڤيد-19

خلال عامي 2020 و2021، قدم العلماء ووسائل الإعلام مراجعات متباينة حول تعامل ديسانتيس مع جائحة كوڤيد-19.[155][156][157]

اعتبارًا من أكتوبر 2021، كان معدل الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر في فلوريدا هو 24، من أعلى المعدلات في البلاد؛ في الفترة من مارس 2020 حتى 22 مارس 2023، كان لفلوريدا المركز الثاني عشر في أعلى معدل في الحالات والوفيات لكل 100.000 شخص بين الولايات الخمسين وواشنطن العاصمة وبورتوريكو، دون تعديل عمر السكان المسنين في فلوريدا.[158][159]

بحلول عام 2023، اعترف العديد من علماء السياسة بأن إدارة ديسانتيس للجائحة ربما تكون قد أفادت منه في حملته لإعادة انتخابه، وكان له الفضل في تحويل "سياساته المتعلقة بڤيروس كورونا إلى مثال عن الحرية الأمريكية".[160][161]

الجائحة في 2020

بحلول 11 مارس 2020، خلصت مراكز السيطرة على الأمراض (CDC) إلى أن انتشار الجائحة في المجتمع قد حدث داخل فلوريدا.[162] بعد النظر في الأمر لبضعة أسابيع،[163][164] في 1 أبريل، أصدر ديسانتيس أمرًا تنفيذيًا يقيد الأنشطة داخل الولاية باستثناء الخدمات الأساسية.[165] بحلول يونيو، كان قد تبنى نهجًا أكثر استهدافًا، حيث أعلن في منتصف يونيو:

لن نغلق أبوابنا، سنمضي قدمًا، وسنواصل حماية الفئات الأكثر ضعفًا ... خاصة عندما يكون لديك ڤيروس يؤثر بشكل غير متناسب على شريحة واحدة من المجتمع، لقمع الكثير من الأشخاص في سن العمل في هذه المرحلة، لا أعتقد أنه من المحتمل أن يكون فعالًا للغاية.[166]

كان هذا النهج مشابهًا للنهج الموصى به بعد بضعة أشهر في بيان بارينجتون العظيم.[167] حصل ديسانتيس على لقاح كوڤيد-19، وأعرب عن حماسه للأشخاص الذين يتلقون اللقاح، لكنه عارض المطالبة بتلقيه.[168]

في أوائل يونيو، رفع ديسانتيس جزئيًا أمر البقاء في المنزل، ورفع القيود المفروضة على الحانات ودور السينما ؛ في نفس اليوم الذي رفع فيه القيود، سجلت فلوريدا أكبر زيادة في الحالات في ستة أسابيع.[155] رفض ديسانتيس تطبيق قانون الإلزام بارتداء قناع الوجه على مستوى الولاية، والسماح بتنفيذ أمر البقاء في المنزل في أبريل.[155] وأعلن أنه سيعيد بعض القيود المفروضة على النشاط التجاري في أواخر يونيو لوقف انتشار الڤيروس، لكنه قال إن فلوريدا "لن تتراجع" عن إعادة فتح الأنشطة الاقتصادية، بحجة أن "الأشخاص الذين يذهبون إلى الأعمال التجارية ليس هو الدافع" للزيادة في حالات.[169] في 25 سبتمبر، رفعت فلوريدا جميع قيود السعة المتبقية على الشركات، بينما منعت أيضًا الحكومات المحلية من إنفاذ أوامر الصحة العامة بغرامات، أو تقييد المطاعم إلى أقل من 50 بالمائة من طاقتها.[170][171][172] حث ديسانتيس مسؤولي الصحة العامة في مدن فلوريدا على التركيز بشكل أقل على اختبار كوڤيد-19 الشامل والمزيد على اختبار الأشخاص الذين يعانون من الأعراض.[173]

فضل ديسانتيس إعادة فتح المدارس للتعلم الشخصي للعام الدراسي 2020-2021.[174] بحلول أكتوبر، أعلن أن جميع مناطق المدارس العامة الـ 67 مفتوحة للتعلم الشخصي.[174]

وفقًا لمركز السيطرة على الأمراض، انخفض متوسط العمر المتوقع خلال عام 2020 في فلوريدا إلى 77.5 سنة من 79 سنة في 2019؛ كان ذلك الخريف الذي دام 1.5 عام في فلوريدا أقل من الانخفاض على مستوى البلاد البالغ 1.8 سنة.[175][176][177] كان الانخفاض على مستوى الولاية وعلى مستوى البلاد في متوسط العمر المتوقع "يرجع في الغالب إلى جائحة كوڤيد-19 والزيادات في الإصابات العرضية"، حيث تُعزى الوفيات غير المقصودة في الغالب إلى الجرعات الزائدة من المخدرات.[175][176][177]

الجائحة في 2021

بحلول فبراير 2021، كان لدى ديسانتيس تقييمات موافقة إيجابية بشكل عام، تتراوح من 51 إلى 64 بالمائة.[178][179][180] في الشهر نفسه، نظرة إدارة بايدن في فرض قيود سفر على فلوريدا والمواقع المحلية الأخرى لمنع انتشار كوڤيد-19،[181][182] وتعهد ديسانتيس بمعارضة أي جهد "لإغلاق حدود فلوريدا".[183][184] في مارس 2021، وصفت "پوليتيكو" ديسانتيس بأنه الحاكم الأكثر "صعودًا سياسيًا" في البلاد، حيث كانت سياساته المثيرة للجدل في تلك المرحلة "أقل من أو حتى معاكسة للدمار"، في حين أن فلوريدا "لم تحقق أي شيء أسوأ، وفي بعض النواحي أفضل من ولايات أخرى".[185]

أدى الطرح الأولي لللقاحات في فلوريدا أوائل عام 2021 إلى ظهور شكاوى مختلفة حول المحسوبية تجاه المساهمين في الحملة والتمييز ضد المجتمعات التي كانت في الغالب ديمقراطية أو فقيرة أو تقطنها أقليات عرقية.[186][187] نفى ديسانتيس المحسوبية المزعومة، ودافع عن طريقة تعامله مع توزيع اللقاح.[186][188]

بحلول أبريل 2021، كانت فلوريدا في المرتبة 27 من أصل 50 في كل من الحالات والوفيات للفرد.[189]

في مايو 2021، ألغى ديسانتيس حالة الطوارئ وجميع أوامر الصحة العامة المتعلقة بكوڤيد-19، على مستوى الولاية.[190][191][192]

في نفس اليوم، وقع مشروع قانون يحظر على الشركات والسفن السياحية والمدارس والهيئات الحكومية طلب إثبات التطعيم لاستخدام الخدمات.[193][194] وسط عودة ظهور الإصابات الجديدة في يوليو،[195] منع ديسانتيس المدارس العامة من تنفيذ الإلزام بارتداء القناع وبالتالي ترك ارتداء الأقنعة لأولياء أمور الطلاب، على الرغم من أنه نصحهم بعدم القيام بذلك لأنه "من غير المريح جدًا [للأطفال] القيام بذلك؛ ليس هناك الكثير من العلم وراء ذلك."[196][197][198] في وقت لاحق من عام 2021، استبدل الأمر التنفيذي المتعلق بارتداء القناع بقانون ولاية جديد وقع عليه ديسانتيس وهو يحقق نفس الشيء.[199]

بحلول أغسطس 2021، وسط رقم قياسي في الحالات الجديدة داخل الولاية، أصبحت فلوريدا الولاية التي لديها أعلى معدل دخول للفرد في المستشفيات بسبب كوڤيد-19.[200] عارض ديسانتيس تأكيد الرئيس جو بايدن على أن فلوريدا لا تفعل ما يكفي لمكافحة الجائحة.[201][202] كما جادل بأن بايدن كان يسمح بانتقال كوڤيد-19 عبر الحدود الجنوبية للولايات المتحدة.[201][203] أفادت واشنطن پوست أن هذا الادعاء كان يستند إلى "التخمين والافتراضات، وليس الأدلة ، بينما ذكرت "پوليتيفاكت" أن البؤر الساخنة لكوڤيد-19 تميل إلى التجمع بعيدًا عن الحدود، في الأماكن ذات معدلات التطعيم العامة المنخفضة، وليس على امتداد الحدود الجنوبية، كما كان متوقعًا إذا كان المهاجرون هم من يقودون الزيادة في عدد الحالات.[201][203]

واصل ديسانتيس اتخاذ الإجراءات المتعلقة بكوڤيد-19 خلال الفترة المتبقية من عام 2021، بما في ذلك معاقبة اشتراط تلقي اللقاح من الوكالات الحكومية المحلية،[204][205] وعين طبيب يشببه في التفكير، جوزيف لاداپو، كجراح عام لولاية فلوريدا،[206][207][208][209] وقام بتجنيد ضباط شرطة من خارج الولاية للانتقال والعمل في فلوريدا، بما في ذلك الضباط الذين سعوا لتجنب متطلبات اللقاح في ولاياتهم الأصلية.[210] لاداپو، أحد الموقعين على بيان بارينجتون العظيم ،[211] كان له تاريخ في الترويج للعلاجات غير المثبتة لكوڤيد-19، ومعارضة متطلبات لقاح كوڤيد-19، والتشكيك في سلامة لقاحات كوڤيد-19.[207][209]

في نوفمبر 2021، وقع ديسانتيس على حزمة تشريعية جعلت فلوريدا أول ولاية[212] تفرض غرامات على الشركات والمستشفيات التي تتطلب تطعيم كوڤيد-19 دون استثناءات أو بدائل.[213][214][215]

الجائحة في 2022 و2023

شهدت فلوريدا نموًا اقتصاديًا وسكانيًا سريعًا عامي 2022 و2023، إلى جانب فائض قياسي في ميزانية الولاية.[216][217][218]

في يونيو 2022، قرر ديسانتيس عدم طلب لقاحات كوڤيد-19 للأطفال دون سن الخامسة، مما جعل فلوريدا الولاية الوحيدة التي لم تطلب اللقاحات مسبقًا لتلك الفئة السكانية.[219]

في يناير 2023، أعلن ديسانتيس عن اقتراح بحظر كوڤيد-19 بشكل دائم في فلوريدا. يتضمن الاقتراح حظرًا دائمًا لمتطلبات الأقنعة في جميع أنحاء الولاية، ومتطلبات اللقاح والأقنعة في المدارس، وجوازات سفر كوڤيد-19 في الولاية، وأرباب العمل الذين يقومون بالتوظيف أو التسريح بناءً على لقاحات كوڤيد-19.[220]

التعليم

في 14 سبتمبر 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس أن فلوريدا ستستبدل اختبار تقييم معايير فلوريدا (FSA) بنظام اختبارات أصغر منتشر على مدار العام. قال إنه ستكون هناك ثلاثة اختبارات، في الخريف والشتاء والربيع، كل منها أصغر من تقييم معايير فلوريدا. وافق مفوض التعليم في فلوريدا ريتشارد كوركوران على القرار، واصفا إياه بأنه "انتصار كبير للنظام المدرسي". سيتم تنفيذ النظام الجديد بحلول العام الدراسي 2022-2023.[221]

في مارس 2021، اقترح ديسانتيس تشريعًا لفرض قيود ومتطلبات أكثر صرامة على جامعات فلوريدا للتعاون مع الأكاديميين والجامعات الصينية؛ قال إن هذا سيقمع التجسس الاقتصادي من قبل الصين.[222][223][224][225] في يونيو وقع ديسانتيس مشروعي قوانين من هذا النوع.[226]

النظرية العرقية النقدية في المدارس

في يونيو 2021، قاد ديسانتيس جهدًا لحظر تدريس النظرية العرقية النقدية في مدارس فلوريدا الحكومية (على الرغم من أنها لم تكن جزءًا من منهج المدارس الحكومية في فلوريدا). ووصف نظرية العرق النقدية بأنها "تعليم الأطفال أن يكرهوا بلادهم"، مما يعكس دفعة مماثلة من قبل المحافظين على الصعيد الوطني.[227] في 10 يونيو وافق مجلس فلوريدا للتعليم على الحظر. انتقدت جمعية فلوريدا للتعليم الحظر، متهمة المجلس بمحاولة إخفاء الحقائق عن الطلاب. ادعى منتقدون آخرون أن الحظر كان محاولة "لتسييس التعليم في الفصول الدراسية وتبييض التاريخ الأمريكي".[228]

في 15 ديسمبر 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس عن مشروع قانون جديد، قانون أوقفوا الأخطاء لأطفالنا وموظفينا ("Stop WOKE Act"، والذي سيسمح للآباء بمقاضاة المناطق التعليمية التي تعلم النظرية العرقية النقدية. تم تصميم مشروع القانون لمكافحة "يقظة التلقين العقائدي" في الشركات والمدارس في فلوريدا عن طريق منع التعليمات التي قد تجعل بعض الناس يشعرون أنهم يتحملون "المسؤولية الشخصية" عن الأخطاء التاريخية بسبب عرقهم أو جنسهم أو أصلهم القومي، مما يمنع التعليمات التي تعلم أن الناس "بطبيعتهم عنصريون أو متحيزون جنسيًا أو قمعي، سواء بوعي أو بغير وعي"، ومنع التعليمات التي تعلم أن مجموعات من الناس مضطهدة أو مميزة على أساس العرق أو الجنس أو الأصل القومي. قال عن مشروع القانون، "يجب عدم استخدام أموال دافعي الضرائب لتعليم أطفالنا أن يكرهوا بلدنا أو يكرهوا بعضهم البعض.[229][230][231][232] في 18 أغسطس 2022، منع قاض في فلوريدا القانون، قائلاً إنه ينتهك التعديل الأول للدستور وهو غامض للغاية.[233]

قضايا المثلية الجنسية في المدارس

في 1 يونيو 2021، وقع ديسانتيس على قانون الإنصاف في الرياضات النسائية (SB 1028). وهو يحظر الفتيات والنساء المتحولات جنسياً من المشاركة والمنافسة في المسابقات الرياضية النسائية في المدارس الإعدادية والثانوية والكليات في فلوريدا. دخل القانون حيز التنفيذ في 1 يوليو.[234][235][236]

في فبراير 2022، أعرب ديسانتيس عن دعمه قانون فلوريدا للحقوق الأبوية في التعليم (HB1557 ، المعروف باسم قانون "لا تقل مثلي" ، والذي يحظر مناقشة التوجه الجنسي أو هوية النوع في الفصول الدراسية بالمدرسة من روضة الأطفال إلى الصف الثالث. قال إنه "من غير المناسب تمامًا" للمعلمين ومديري المدارس التحدث إلى الطلاب حول هويتهم الجنسية.[237][238][239] في 28 مارس 2022 وقع ديسانتيس مشروع القانون (مشروع القانون رقم 1557 بمجلس النواب) لقانون،[240] ودخل حيز التنفيذ في 1 يوليو.[241] يتضمن هذا النظام الأساسي أيضًا بندًا "يتطلب من موظفي منطقة المدرسة تشجيع الطالب على مناقشة القضايا المتعلقة برفاهه أو سلامتها مع والديه أو والديها أو لتسهيل مناقشة المشكلة مع الوالد"، ولا يقصر هذه القضايا على الميول الجنسية أو الهوية الجنسية.[242] اعتبارًا من مارس 2023، كان ديسانتيس يفكر في مزيد من التشريعات المماثلة لجميع الصفوف.[243][244]

في 19 أبريل، مدد مجلس التعليم بالولاية قيود القانون على التدريس في الفصول الدراسية إلى الصفوف من 4 إلى 12، ما لم يكن التعليم مطلوبًا وفقًا لمعايير الولاية الحالية أو كان جزءًا من دورة اختيارية حول الصحة الإنجابية.[245][246]

دعت شركة والت ديزني، مالكة عالم والت ديزني في فلوريدا، إلى إلغاء القانون، وبدء نزاع بين ديزني وحكومة الولاية. [247] في أبريل 2022، وقع ديسانتيس على مشروع قانون يلغي قانون المنطقة المستقلة الخاصة واستبدال مجلس المشرفين المعين من ديزني.[248][249] كما هدد خلال مؤتمر صحفي ببناء سجن حكومي جديد بالقرب من مجمع عالم ديزني.[250] في 26 أبريل 2023، رفع ديزني دعوى ضد ديسانتيس وآخرين، متهمة إياهم باستخدام السلطة السياسية بغرض "الانتقام الحكومي".[251]

الاقتصاد

أثناء حملته الانتخابية 2018، تعهد ديستانتيس بتخفيض ضرائب الدخل على شركات إلى 5٪ أو أقل.[252] خلال فترة ولايته، انخفضت ضرائب دخل الشركات في فلوريدا إلى 3.5 في المائة عام 2021، ولكن بحلول عام 2022 ارتفعت إلى 5.5 في المائة.[253]

حافظ ديسانتيس على الوضع الضريبي المنخفض لفلوريدا خلال فترة عمله كحاكم.[254]

في يونيو 2019، وقع ديسانتيس على ميزانية قدرها 91.1 مليار دولار أقرها المجلس التشريعي الشهر السابق، والتي كانت الأكبر في تاريخ الولاية في ذلك الوقت، على الرغم من أنه خفض الاعتمادات 131 مليون دولار.[255][256]

في يونيو 2021، وقع على ميزانية قدرها 101.5 مليار دولار تضمنت 169 مليون دولار للإعفاء الضريبي.[257]

طوال 2019، ظل معدل البطالة في فلوريدا أقل من 5 في المائة.[258]

الحجر المنزلي المتعلق بجائحة كوڤيد-19 في أوائل عام 2020، شهدت فلوريدا، ومعظم الولايات الأخرى، معدلات بطالة تقارب 15%.[258][259][260]

ألقى ديسانتيس باللوم جزئيًا على سلفه الحاكم، ريك سكوت، لتركه نظام بطالة موهن أدى إلى تراكم الأعمال المتراكمة حيث أضرت جائحة كوڤيد-19 باقتصاد الولاية.[261]

بعد ذلك، بدأ اقتصاد فلوريدا في التعافي بسرعة، وانخفض معدل البطالة إلى أقل من 7% بحلول النصف الثاني من عام 2020.[262]

في ديسمبر 2020، أمر ديسانتيس وزارة فلوريدا للفرص الاقتصادية بتمديد إعفاءات البطالة حتى 27 فبراير 2021.[263] منذ مايو 2022، بلغ معدل البطالة في فلوريدا حوالي 2%، أي أقل من المتوسط الوطني.[254][258]

الهجرة

سعى ديسانتيس إلى حظر "مدن الملاذ الآمن".[264] في يونيو 2019، وقع مشروع قانون ضد "المدن الملاذ" ليصبح قانونًا. لم يكن في فلوريدا أي مدن ملاذ قبل سن القانون، ووصف دعاة الهجرة مشروع القانون بأنه ذو دوافع سياسية.[265][266][267] خصصت إدارة ديسانتيس 12 مليون دولار لنقل المهاجرين إلى ولايات أخرى.[268]

في سبتمبر 2022، بعد إجراءات مماثلة من قبل حاكم ولاية تكساس جريج أبوت، قام وكيل ديسانتيس بتجنيد 50 طالب لجوء وصلوا حديثًا، معظمهم من ڤنزويلا، في سان أنطونيو، تكساس، ونقلهم عبر طائرتين مستأجرتين إلى مطار كرستڤيو، فلوريدا، حيث لم يتم إنزالهم، ثم نُقلوا إلى مارثا ڤينيارد، مساتشوستس. ادعى محامون يمثلون المهاجرين أنه تم الكذب على اللاجئين ووعدوا بوظائف وتمويل ودروس اللغة الإنجليزية والخدمات القانونية والمساعدة في الإسكان في وجهتهم.[269]

خصص المجلس التشريعي في فلوريدا 12 مليون دولار لنقل المهاجرين خارج الولاية، بتمويل تحت إشراف المحامي لاري كيفي، قيصر السلامة العامة في إدارة ديسانتيس، الذي كان مسؤولاً عن شؤون المهاجرين وله علاقة سابقة بشركة النقل الجوي. مقابل النقل حصلت ڤرتول على 615 ألف دولار في 8 سبتمبر، وحصلت على 980 ألف دولار أخرى بعد أقل من أسبوعين. لم تخطر الوجهة بوصول اللاجئين الوشيك ومتطلباتهم.[269][270][268][271][272] ورفع المهاجرون دعوى جماعية ضد ديسانتيس، ووصفوا معاملته لهم بأنها "متطرفة وشائنة ولا تطاق في مجتمع متحضر".[273]

Hurricane Ian

DeSantis was widely praised for the state's response to Hurricane Ian — the deadliest hurricane to hit Florida in over 85 years.[274][275][276] In September 2022, DeSantis declared a state of emergency for all of Florida as Ian approached and asked for federal aid ahead of time.[277][278][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] On October 5, after Ian deserted Florida, President Biden arrived in Florida and met with DeSantis and Senators Marco Rubio and Rick Scott.[279] DeSantis and Biden held a press conference in Fort Myers to report on the status of the cleanup.[280] In addition, DeSantis partnered with Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX and Tesla, Inc., to use the Starlink satellite Internet service to help restore communication across the state.[281]

First lady Casey DeSantis partnered with State Disaster Recovery Mental Health Coordinator Sara Newhouse and the Department of Health and Department of Children and Families to deploy free mental health resources to communities Ian affected.[282]

Abortion

Following the U.S. Supreme Court decision Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade, DeSantis pledged to "expand pro-life protections".[283] On April 14, 2022, he signed into law a bill that regulates elective abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy; under the previous law, the limit had been 24 weeks.[284] The law includes exceptions for abortions beyond 15 weeks if it is necessary to avert "serious risk" to the pregnant woman's physical health or if there is a "fatal fetal abnormality", but does not make exceptions for rape, human trafficking, incest, or mental health.[285]

The law was expected to go into effect on July 1,[286] but a state judge blocked its enforcement, ruling that the Florida Constitution guarantees a right to privacy that renders the law unconstitutional.[287][288] After DeSantis appealed the ruling, the law went into effect on July 5, pending judicial review.[289] In January 2023, the Supreme Court of Florida agreed to hear a legal challenge to the law.[290]

In March 2023, DeSantis said in a press conference of SB300, which bans abortions after six weeks with exceptions to 15 weeks for rape and incest: "I think those exceptions are sensible. We welcome pro-life legislation."[291] Floridian physicians have expressed concern about the bill; most major medical societies such as AMA,[292] ACOG,[293] and AAP[294] consider abortion essential and life-saving health care, but SB300 will make providing abortion punishable by up to five years in prison.[295][291] DeSantis signed the bill into law on April 14, 2023.[296][297]

Gun law

After the 2018 Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, DeSantis expressed support for hiring retired law enforcement officers and military veterans as armed guards for schools.[298] He disagreed with legislation Governor Rick Scott signed that banned bump stocks, added a mandatory three-day waiting period for gun purchases, and raised the legal age for purchases from 18 to 21.[32] He has expressed support for measures to improve federal background checks for purchasing firearms and has said that there is a need to intervene with those who exhibit warning signs of committing violence instead of waiting until a crime has been committed.[298]

In November 2020, DeSantis proposed an "anti-mob" extension to the preexisting stand-your-ground law in Florida that would allow gun-owning residents to use deadly force on people they believe are looting. It would also make blocking traffic during a protest a third-degree felony and impose criminal penalties for partaking in "violent or disorderly assemblies".[299]

On April 3, 2023, DeSantis signed HB 543 into law, which allows Florida residents to carry concealed handguns without a permit. The law will go into effect on July 1, 2023.[300]

إنفاذ القانون

يعارض ديسانتيس الجهود الرامية إلى إيقاف تمويل الشرطة، وقد قدم كمحافظ مبادرات "لتمويل الشرطة".[301] في سبتمبر 2021، قدم 5000 دولار كمكافأة توقيع لضباط شرطة فلوريدا في محاولة لجذب مجندين من الشرطة خارج الولاية.[302]

في أبريل 2021، وقع ديسانتيس على قانون مكافحة الشغب العام الذي كان يدعو إليه. بصرف النظر عن كونه قانونًا لمكافحة الشغب، فقد منع الترهيب من الغوغاء؛ معاقبة الضرر الذي لحق بالممتلكات التاريخية أو النصب التذكارية، مثل تمثال كريستوفر كولومبوس في وسط مدينة ميامي، والذي تعرض للتلف عام 2020؛ وحظر نشر معلومات التعريف الشخصية عبر الإنترنت بقصد الإضرار.[303]

دافع ديسانتيس عن هذا التشريع من خلال الاستشهاد باحتجاجات جورج فلويد 2020 وهجوم كاپيتول الولايات المتحدة 2021، على الرغم من ذكر الأول فقط في مراسم التوقيع.[304] بعد عدة أشهر من التوقيع، منع قاضٍ فيدرالي جزءًا من القانون الذي قدم تعريفًا جديدًا "للشغب"، واصفا إياه بأنه غامض للغاية.[305]

في 5 مايو 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس أن جميع ضباط شرطة فلوريدا ورجال الإطفاء والمسعفين سيحصلون على مكافأة قدرها 1000 دولار.[306]

في 2 ديسمبر 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس أنه كجزء من اقتراح تمويل بقيمة 100 مليون دولار للحرس الوطني في فلوريدا، سيتم تخصيص 3.5 مليون دولار لإعادة تنشيط حرس ولاية فلوريدا، وهو متطوع في قوات دفاع الولاية التي كانت غير نشطة منذ عام 1947.[307][308]

البيئة

أطلق ديسانتيس على نفسه اسم "مناصر لسياسة ثيودور روزڤلت المحافظة". خلال تقلده منصب حاكم الولاية عام 2018، قال أنه لم ينكر وجود تغير المناخ، لكنه لا يريد أن يوصف بأنه "مؤمن بتغير المناخ"،[309] مضيفًا، "أعتقد أننا نساهم في التغييرات في البيئة، لكنني لست في المقاعد المتبقية من ظاهرة الاحتباس الحراري".[310]

عام 2019 وقع ديسانتيس على أمر تنفيذي يتضمن مجموعة متنوعة من المكونات المتعلقة بالبيئة.[311] وشمل ذلك وعدًا بإنفاق 2.5 بليون دولار على مدى أربع سنوات على استعادة إيڤرجليدز و"حماية المياه الأخرى"، وإنشاء فرقة عمل الطحالب الزرقاء والخضراء، ومكتب المساءلة البيئية والشفافية، ورئيس قسم العلوم.[311] كما استبدل مجلس منطقة جنوب فلوريدا لإدارة المياه بالكامل.[312]

في 10 يوليو 2020، أعلن ديسانتيس أن فلوريدا ستنفق 8.6 مليون دولار من أصل 166 مليون دولار تلقتها الولاية من تسوية قانونية بين ڤولكس ڤاجن ووزارة العدل الأمريكية فيما يتعلق بانتهاكات الانبعاثات لإضافة 34 محطة شحن للسيارات الكهربائية. ستكون المحطات على امتداد الطرق السريعة 4، 75، 95، 275 و295.[313] في 16 يونيو 2021، وقع ديسانتيس على قانون مجلس النواب رقم 839، الذي يحظر على الحكومات المحلية في فلوريدا مطالبة محطات الوقود بإضافة محطات شحن السيارات الكهربائية.[314]

في 21 يونيو 2021، وقع ديسانتيس على قانون مجلس النواب رقم 919، الذي يحظر على الحكومات المحلية فرض حظر أو قيود على أي مصدر للكهرباء. عدة مدن كبيرة في فلوريدا في ذلك الوقت (أورلاندو، سانت بطرسبرج، تالاهاسي، دنيدن، لارجو، ساتالايت بيتش، جينزڤل، ساراسوتا، سيفتي هاربر وميامي بيتش) وضعوا أهدافًا لتحقيق جميع طاقتهم من مصادر متجددة. تم وصف مشروع القانون بأنه مشابه لتلك الموجودة في ولايات أخرى (تكساس وتينيسي ولويزيانا وأريزونا وأوكلاهوما) التي أقرت قوانين تمنع المدن من حظر وصلات الغاز الطبيعي.[315][316]

كما وقع ديسانتيس على مشروع قانون لتحفيز ممرات الحياة البرية.[317]

حقوق التصويت والانتخابات

أعرب ديسانتيس عن دعمه مبادرة استعادة حقوق التصويت للمجرمين بعد إقراره في نوفمبر 2018، قائلاً إنه "ملزم بتنفيذ [ذلك] بأمانة كما هو محدد" عندما أصبح حاكمًا. بعد أن رفض استعادة حقوق التصويت للمجرمين بغرامات غير مدفوعة، والتي قالت جماعات حقوق التصويت إنها تتعارض مع نتائج الاستفتاء، تم الطعن فيه في المحكمة. وقفت المحكمة العليا في فلوريدا مع ديسانتيس في هذه القضية،[318] كما انحازت محكمة الاستئناف للدائرة الحادية عشرة إلى ديسانتيس في حكم بتصويت 6-4 من هيئة المحلفين.[319]

في أبريل 2019، وجه ديسانتيس رئيس انتخابات فلوريدا لتوسيع توافر بطاقات الاقتراع باللغة الإسبانية والمساعدة الإسبانية للناخبين. في بيان، قال ديسانتيس: "من الأهمية بمكان أن يتمكن سكان فلوريدا الناطقون بالإسبانية من ممارسة حقهم في التصويت دون أي حواجز لغوية".[320]

في يونيو 2019، وقع ديسانتيس على إجراء من شأنه أن يجعل من الصعب إطلاق مبادرات اقتراع ناجحة. كما جمعت الالتماسات لمبادرات الاقتراع لإضفاء الشرعية على القنب الطبي، وزيادة الحد الأدنى للأجور، وتوسيع برنامج ميديك إيد.[321][322][323] أصدر ديسانتيس أمراً للمدعي العام في فلوريدا أشلي مودي بالتحقيق فيما إذا كان مايكل بلومبيرج قد عرض حوافز جنائية على المجرمين للتصويت من خلال المساعدة في جهود جمع التبرعات لسداد التزاماتهم المالية حتى يتمكنوا من التصويت في الانتخابات الرئاسية لعام 2020 في فلوريدا. ولم يُعثر على مخالفات.[324]

في فبراير 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس دعمه لعدة قيود لقانون الانتخابات.[325][326][327][328]

ودعا إلى إلغاء صناديق الاقتراع والحد من التصويت بالبريد من خلال مطالبة الناخبين بإعادة التسجيل كل عام للتصويت بالبريد وأن تتطابق التوقيعات على بطاقات الاقتراع عبر البريد "مع أحدث توقيع في الملف "(بدلاً من أي من توقيعات الناخبين في نظام فلوريدا الانتخابي).[329][330] كانت التغييرات في التصويت بالبريد ملحوظة بالنظر إلى أن الجمهوريين صوتوا تاريخيًا بالبريد أكثر من الديمقراطيين، لكن الديمقراطيين تفوقوا على الجمهوريين عن طريق البريد عام 2020.[329] وفقًا لتحليل "تامپا باي تايمز"، كان من الممكن أن يؤدي اقتراح مبادرة توقيع ديسانتيس إلى رفض بطاقات الاقتراع الخاصة به عبر البريد بسبب التغييرات في سجل توقيعه بمرور الوقت؛ جادل الخبراء بأنه يمكن استخدام اقتراح مطابقة التوقيع لإبطال حق التصويت للناخبين الذين اختلفت توقيعاتهم بمرور الوق.[330]

شركات التكنولوجيا

في 2 فبراير 2021، أعلن ديسانتيس دعمه تشريع لقمع عمالقة التكنولوجيا ومنع الرقابة السياسية المزعومة .[331][332]

رداً على شبكات التواصل الاجتماعي التي أزالت ترمپ من منصاتها، دفع ديسانتيس وغيره من الجمهوريين في فلوريدا تشريعاً في الجمعية التشريعية في فلوريدا لحظر شركات التكنولوجيا من إلغاء برامج المرشحين السياسيين.[333]

منع قاض فيدرالي القانون من خلال أمر قضائي أولي في اليوم السابق لدخوله حيز التنفيذ، على أساس أنه ينتهك التعديل الأول والقانون الفدرالي.[334]

عندما علق تويتر حساب ربيكا جونز، التي تنتقد ادارة ديسانتيس، لانتهاكها قواعد البريد العشوائي والتلاعب بالمنصة، أشاد مكتب ديسانتيس بالقرار ووصفه بأنه "طال انتظاره".[335][336]

عقوبة الإعدام

بصفته حاكمًا، أشرف ديسانتيس على إعدام خمسة سجناء، جميعهم مدانين بالقتل.[337][338][339][340][341]

عام 2022، انتقد ديسانتيس عقوبة السجن المؤبد التي أقرتها هيئة المحلفين على مطلق النار في مدرسة باركلاند، بدلاً من عقوبة الإعدام. في تلك القضية، أيد تسعة محلفين حكم الإعدام، لكن ثلاثة أوقفوه.[342] في أبريل 2023، وقع ديسانتيس قانونًا (مشروع قانون مجلس الشيوخ 450) يسمح لهيئة المحلفين بفرض عقوبة الإعدام إذا وافق ثمانية على الأقل من 12 محلفًا.[343][344]

في مايو 2023، وقع ديسانتيس قانونًا يسمح للمدانين باغتصاب أطفال تحت سن 12 عامًا بالحصول على عقوبة الإعدام، متحديًا و"طعنًا" أمام حكم المحكمة العليا في قضية "كنيدي ضد لويزيانا".[345][346]

حملة الانتخابات الرئاسية 2024

بين عامي 2021 و2023، حث العديد من الشخصيات البارزة ديسانتيس على الترشح للرئاسة في انتخابات 2024. في سبتمبر 2021، وصف تكهنات 2024 بأنها "مصطنعة بحتة".[347]

في أبريل 2023، قال ديسانتيس: "أنا لست مرشحًا، لذلك سنرى ما إذا كان ذلك سيتغير ومتى"؛ في ذلك الوقت، كان ترمپ يتقدم على ديسانتيس في استطلاعات الرأي لمرشحي الحزب الجمهوري، لكن أداء ديسانتيس كان أفضل من أداء ترمپ في الاقتراع على الأرض في الانتخابات العامة.[348][349]

في استطلاع للرأي أجراه مؤتمر العمل السياسي للمحافظين عام 2022 حول المرشحين الرئاسيين للحزب الجمهوري 2024، جاء ديسانتيس في المرتبة الثانية بنسبة 28% من الأصوات، بعد ترمپ، الذي حصل على 59%.[350]

منذ عام 2022، يُنظر إلى ديسانتيس بشكل متزايد على أنه منافس لترشيح الحزب الجمهوري. توقع العديد من الكتاب أنه قد يهزم ترمپ أو قالوا إنه أفضل من ترمپ في ضوء جلسات 6 يناير واستطلاعات الرأي التالية.[351][352][353]

اكتسبت هذه الأفكار المزيد من الزخم بعد انتخابات التجديد النصفي لعام 2022، عندما أعيد انتخاب ديسانتيس حاكمًا بحوالي 20 نقطة مئوية، في حين أن المرشحين المدعومين من ترمپ، مثل محمد أوز في انتخابات مجلس الشيوخ في پنسلڤانيا، كان أداءهم سيئًا.[354][355] كما أدى إصدار مذكرات ديسانتيس، "الشجاعة لتكون حرًا"، وجولة الكتاب اللاحقة، أيضًا على زيادة التكهنات عام 2024.[356]

في 24 مايو 2023، أطلق ديسانتيس رسميًا حملته الانتخابية.[357] أعلن ديسانتيس عن ترشحه على تويتر، بمساعدة مالكه إلون ماسك.[358]

حياته الشخصية

التقى ديسانتيس بزوجته كيسي بلاك، في ملعب جولف بجامعة شمال فلوريدا.[359] كانت مذيعة تلفزيونية في قناة الجولف، ثم صحفية تلفزيونية ومراسلة أخبار في WJXT.[360][359] تزوجا في 26 سبتمبر 2009، في كنيسة في منتجع وسبا ديزني جراند فلوريديان.[359][361][362] ديسانتيس كاثوليكي وقد تم عقد الزواج على يد قس كاثوليكي.[362][363]

عاش الزوجان في پونتي ڤدرا بيتش، بالقرب من سانت أوجستين، حتى انتقالهما إلى منطقة الكونجرس الرابعة المجاورة. ثم انتقلوا إلى پالم كوست شمال دايتونا بيتش.[364][365] لدى الزوجان ثلاثة أنجال.[366]

وهو عضو في المحاربين المتقاعدين من الحروب الأجنبية والفليق الأمريكي.[367] عام 2022، ظهر ديسانتيس على تايم 100، القائمة السنوية التي تصدرها مجلة تايم لأكثر 100 شخص تأثيراً في العالم.[368]

التاريخ الانتخابي

المنشورات

- رون ديسانتيس (2011). أحلام من آبائنا المؤسسين: المبادئ الأولى في عصر أوباما. جاكسونڤل: منشورات هاي-پيتشد هيوم. ISBN 978-1-934666-80-7.[369]

- رون ديسانتيس (2023). الشجاعة لتكون حراً. برودسايد بوكس. ISBN 978-0063276000.

مرئيات

| منصور الضيفي، سجين سابق في معتقل جوانتنامو، يزعم أن ديسانتيس كان يشرف على إطعام المعتقلين قسرياً أثناء خدمته في المعتقل، مايو 2023. |

الهوامش

- ^ DeSantis's great-grandparents were originally from comuni in the provinces of L'Aquila (Cansano, Bugnara, Pacentro and Pratola Peligna, in Abruzzo region), Caserta (Sessa Aurunca, in Campania region), Avellino (Castelfranci, in Campania region) and Campobasso (Castelbottaccio, in Molise region).[8][9][10][11][12] His paternal great-grandfather Nicola DeSantis was originally from Cansano, Abruzzo region.[8] His paternal grandfather was Daniel DeSantis, born in Beaver, Pennsylvania, to Nicola and his wife Maria.[8] DeSantis's maternal great-great-grandfather, Salvatore Storti, immigrated to the U.S. during the Italian diaspora in 1904, eventually settling in Pennsylvania, where his wife Luigia Colucci joined him in 1917.[10]

References

- ^ أ ب ت "Ronald Dion DeSantis - Florida Department of State". dos.myflorida.com. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

Biographical information from the Ron DeSantis transition website

- ^ أ ب Christensen, Dan, ed. (January 2023). "BIOGRAPHICAL DATA". Florida Bulldog. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

Separation Date: Feb. 14, 2019.

- ^ Epstein, Reid J.; McFadden, Alyce (May 24, 2023). "Deh-Santis or Dee-Santis? Even He Has Been Inconsistent". New York Times.

- ^ أ ب Gomez, Henry. "How Midwest roots shaped Ron DeSantis' political values and perspective", NBC News (March 19, 2023).

- ^ Hutchison, Peter (November 9, 2022). "Ron DeSantis, Rising Star Of The Republican Hard-right". Barron's (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ "Obituary: Christina Marie DeSantis (May 05, 1985 - May 12, 2015), Palm Harbor, FL". Curlew Hills Memory Gardens, Inc. May 2015. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2023 – via Obittree.com.

- ^ McCloud, Cheryl (February 28, 2023). "Ron DeSantis: 14 things to know about Florida's governor". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت "Ron DeSantis, governatore in Florida e possibile candidato alla presidenza, ha origini abruzzesi e molisane" [Ron DeSantis, governor of Florida and possible presidential candidate, is originally from Abruzzo and Molise] (in الإيطالية). November 10, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Di Leonardo, Stefano (November 19, 2022). "Origini comuni ma rivali verso la Casa Bianca: DeSantis e McCarthy, la sfida tra i Repubblicani è molisana" [Common origins but rivals toward White House: DeSantis and McCarthy, Republicans challenge Molise] (in الإيطالية). Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ أ ب Contorno, Steve (August 21, 2018). "Immigration hardliner Ron DeSantis' great-great-grandmother was nearly barred from America". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Ron DeSantis, è di Castelfranci il nuovo idolo dei repubblicani statunitensi" [Ron DeSantis, the new idol of the US Republicans is from Castelfranci] (in الإيطالية). November 9, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "Ron DeSantis stravince le Midterm: il "bigotto" peligno opziona la corsa alla Casa Bianca" [Ron DeSantis wins the Midterms hands down: the Peligno "sanctimonius" options the race for the White House] (in الإيطالية). November 9, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Cerabino, Frank (March 24, 2020). "Cerabino: Florida Gov. DeSantis needs to start acting like an Italian mayor". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت Smith, Adam; Leary, Alex (February 18, 2018). "Ron DeSantis: Capitol Hill loner, Fox News fixture, Trump favorite in Florida governor's race". Tampa Bay Times (Digital). Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ McFerren, Robert (August 11, 2022). "Florida Gov. DeSantis's family roots run deep in Valley". WFMJ-TV (Digital). Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ Perry, Mitch (September 8, 2015). "Ron DeSantis admits GOP faithful are 'demoralized, depressed and dejected' at D.C. Republicans". SaintPetersBlog. Extensive Enterprises, LLC. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Cridlin, Jay. “Is DeSantis a hometown hero in this Florida city or just someone who lived there?”, Miami Herald (April 30, 2023).

- ^ "Christina Marie DeSANTIS". Legacy.com. June 7, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ Leary, Alex (May 18, 2015). "Ron DeSantis' sister dies". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ Gonzales, Nathan (June 26, 2012). "Fall Elections Shape Future Rosters". Roll Call. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ أ ب Vaccaro, Ron (March 30, 2001). "Baseball's DeSantis shines on Yale Field of dreams". Yale Daily News. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Mazzei, Patricia (April 10, 2021). "Could Ron DeSantis Be Trump's G.O.P. Heir? He's Certainly Trying". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Morgan, Nancy (June 10, 2001). "Yale grad DeSantis is a hit on, off field". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2001. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Mahoney, Emily L. (October 20, 2018). "Florida governor candidate Ron DeSantis carved aggressive path from Dunedin to D.C." Miami Herald. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ "2001 Yale Baseball Roster". Yale University. Archived from the original on June 29, 2001. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ "Yale University Baseball: Overall Statistics for Yale". Yale University. April 28, 2001. Archived from the original on November 28, 2001. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Mor, Michael (November 5, 2014). "Seventeen Yale alumni won congressional, governor's races on Election Day 2014". YaleNews (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ Robles, Frances (November 5, 2022). "Pranks, Parties and Politics: Ron DeSantis's Year as a Schoolteacher". The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ "Ron DeSantis' Biography". Vote Smart. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ "CANDIDATE Q&A: U.S. House 6, Ron DeSantis". Palm Coast Observer (in الإنجليزية). August 1, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت "About Ron DeSantis". desantis.house.gov. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mahoney, Emily (August 29, 2018). "Who is Ron DeSantis, the Republican running for Florida governor?". The Miami Herald. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mahoney, Emily (August 14, 2018). "This candidate for Florida governor cites serving at Guantánamo. What did he do there?". The Miami Herald. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Wilner, Michael (March 7, 2023). "What's known about Ron DeSantis' time in the Navy at Guantanamo Bay". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ Rado, Diane (October 15, 2018). "What is and isn't known about Ron DeSantis's Navy career? Records provide a glimpse". Florida Phoenix (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ "Did Ron DeSantis Observe Guantanamo Force-Feeding as Navy JAG?". Snopes (in الإنجليزية). 2023-05-01. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- ^ "See No Evil: The business of books and the merger that wasn't". Harper's Magazine (in الإنجليزية). Vol. March 2023. February 17, 2023. ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ Wilner, Michael (March 7, 2023). "'Very Intimate Knowledge': What Ron DeSantis saw while serving at Guantanamo". Miami Herald.

- ^ Hall, Richard (March 17, 2023). "Former Guantanamo prisoner: Ron DeSantis watched me being tortured". The Independent (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved March 17, 2023.

The United Nations has characterised the force-feeding of hunger strikers at Guantanamo Bay as torture. The US government has denied that the practice amounts to torture, and it has been used against prisoners over successive administrations during hunger strikes.

- ^ أ ب Farrington, Brenda (May 5, 2015). "Republican Congressman DeSantis to run for Rubio Senate seat". Sun Sentinel. Associated Press. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ Altman, Howard; Mahoney, Emily (September 21, 2018). "What did Ron DeSantis do during his tour in Iraq?". Tampa Bay Times (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Mahoney, Emily L.; Altman, Howard (August 14, 2018). "In bid for Florida governor, Ron DeSantis touts Navy Gitmo experience. But what did he do there?". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ [hthttps://www.staugustine.com/story/news/local/2012/09/08/2012-09-07-1/16166336007/ "August 14, 2012 Primary Election Republican Primary Official Results"]. The St. Augustine Record. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ "Ron DeSantis, Ted Yoho win freshman seats". The Florida Times Union. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ "DeSantis, Mica easily win re-election to Congress". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ "DeSantis wins third term in Congress". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ Stein, Letitia (May 6, 2015). "Florida Congressman Ron DeSantis running for U.S. Senate". Reuters. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Video: Club for Growth backs DeSantis". The Hill. May 6, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ "Rubio decision instantly reshapes Florida races". Politico. June 22, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ "Americans for Prosperity Applauds U.S. Representative Ron DeSantis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Rep. DeSantis Statement on ObamaCare Repeal". May 16, 2013. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014.

- ^ "H.R. 3973 – CBO". Congressional Budget Office. March 10, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ "H.R. 3972 – Summary". United States Congress. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete (March 7, 2014). "House targets Obama's law enforcement". The Hill. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Contorno, Steve (August 10, 2018). "Ron DeSantis wants to lead Florida through hurricanes. He voted against helping Sandy victims". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ "What is the House Freedom Caucus, and who's in it?". Pew Research Center. October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Keller, Michael (February 11, 2013). "This is Your Representative on Guns". The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ Maddock, Preston (February 20, 2013). "Ron DeSantis Put On Spot By Sandy Hook Parents At Florida Town Hall". HuffPost. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ Derby, Kevin (February 24, 2015). "Ron DeSantis Turns Up the Heat on Obama for Failing to Enforce Immigration Laws". Sunshine State News. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ Scanlon, Kate (June 17, 2015). "Before Skeptical Lawmakers, Officials Defend 'Legality' of Obama's Immigration Actions". The Daily Signal. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ "HR3011 Kate's Law". TrackBill. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ "Sheriffs look at options amid DeSantis immigration push". WINK-TV. March 12, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ DeSantis, Ron; Lee, Mike (March 4, 2015). "Break Up the Higher-Ed Cartel". National Review. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (October 7, 2016). "Rubio's score plummets to '0' in HRC congressional ratings". Washington Blade. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Measuring Support for Equality in the 114th Congress | Congressional Scorecard" (PDF). Human Rights Campaign. p. 14.

- ^ Jean, Carline (September 24, 2018). "Ron DeSantis answered question on his stance on gay rights". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Lynch, Sarah and Colvin, Ross. “Gunfire turns U.S. lawmakers' baseball practice into 'killing field'”, Reuters (Jun 14, 2017).

- ^ Shelbourne, Mallory (August 28, 2017). "GOP lawmaker proposes amendment to stop Mueller investigation after 180 days". The Hill. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Wright, Austin (August 28, 2017). "Republican floats measure to kill Mueller probe after 6 months". Politico. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Perez, Evan; Herb, Jeremy; Raju, Manu. "Little chance Congress can kill Mueller's funding". CNN.

- ^ Farrington, Brendan (May 5, 2015). "Republican Congressman DeSantis to run for Rubio Senate seat". Sun-Sentinel. Associated Press. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Man, Anthony (January 12, 2021). "DeSantis calls insurrection 'really unfortunate' and 'really a sad thing to see'". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Derby, Kevin (December 16, 2014). "Despite Opposing 'CRomnibus,' Sophomore Ron DeSantis Ascends Congressional Ladder". Sunshine State News. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ "Member List". Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ Jordan, Douglas (December 16, 2012). "DeSantis emphasizes importance of economic growth". St. Augustine Record. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Wexler, Gene (January 3, 2013). "New St. Johns Rep. opens up on financial and governmental reforms". WOKV. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Siefring, Neil (August 4, 2015). "The REINS Act will keep regulations and their costs in check". The Hill. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Ron DeSantis, R-Fla. (6th District)". Roll Call. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ DeSantis, Ron; Jordan, Jim (July 27, 2015). "The Stonewall at the Top of the IRS". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Perry, Mitch (July 28, 2015). "Ron DeSantis wants Obama to remove IRS commissioner – or else". Florida Politics. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "Resolution Introduced to Impeach IRS Commissioner". House Oversight Committee. October 27, 2015. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "DeSantis: Lois Lerner's Attempt to Exonerate Herself Not Convincing". Press Release. September 22, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014.

- ^ Gancarski, A.G. (July 31, 2015). "Email insights: Ron DeSantis, "Taxpayer Superhero"". Florida Politics. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Guggenheim, Benjamin. “National sales tax becomes focal point for Trump-DeSantis war”, Politico (15 May 2023}.

- ^ Cappabianca, Marina. “A close look into DeSantis' voting record”, Spectrum News NY1 (3 May 2023).

- ^ Derby, Kevin (March 16, 2015). "Marco Rubio, Ron DeSantis Restore 'Let Seniors Work Act'". Sunshine State News. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete. “GOP bill ends taxes on Social Security payments”, The Hill (January 22, 2014).

- ^ أ ب Sherman, Amy. “Fact Check: Adam Putnam ad exaggerates Ron DeSantis votes on Social Security, Medicare”, PolitiFact via WBBH (August 13, 2018).

- ^ أ ب Reyes, Yacob. “DeSantis takes different tack on Social Security, Medicare than when he was in Congress”, Politifact via Tampa Bay Times (March 17, 2023).

- ^ Laing, Keith (June 10, 2015). "Bill filed to sharply reduce the gas tax". The Hill. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Mike; DeSantis, Ron (June 10, 2015). "Economy Commentary Let America Fix the Highways Washington Broke". The Daily Signal. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Dixon, Matt (June 28, 2013). "Retail group assails DeSantis over Internet sales tax". St. Augustine Record. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Almukhtar, Sarah (December 19, 2017). "How Each House Member Voted on the Tax Bill". The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Stephanie (December 19, 2017). "Northeast Florida lawmakers divided on impact of tax reform plan". Wokv.com. WOKV Radio. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Ronald Dion DeSantis". Florida Department of State. Archived from the original on November 19, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Harper, Jennifer (February 2, 2015). "No more 'ruling class culture': New legislation would jettison pensions for Congress". The Washington Times. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "Ron DeSantis files paperwork to run for Governor of Florida". First Coast News News. January 5, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Farrington, Brendan (January 5, 2018). "Trump's tweeted choice for Florida governor enters the race". Associated Press News. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Mahoney, Emily (July 30, 2018). "New lighthearted Ron DeSantis ad features his family, Trump jokes". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (July 30, 2018). "In Florida, Not All Politics Are Local, as Trump Shapes Governor's Race". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ "Andrew Gillum, a Black Progressive, and Ron DeSantis, a Trump Acolyte, Win Florida Governor Primaries". The New York Times. August 28, 2018. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Rohrer, Gray (August 31, 2018). "Florida governor's race: Where Ron DeSantis, Andrew Gillum stand on the issues". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Swisher, Skyler (August 31, 2018). "Where do governor hopefuls Ron DeSantis, Andrew Gillum stand on the issues?". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Ron DeSantis gets solid hits on national issues in Fox News debate". Florida Politics. June 29, 2018.

- ^ Dailey, Ryan (June 29, 2018). "Putnam, DeSantis Find Common Ground Opposing Recreational Pot". News.wfsu.org. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ Clark, Dartunorro; Vitali, Ali (August 29, 2018). "Gillum responds to 'monkey this up' comment: DeSantis is joining Trump 'in the swamp'". NBC News. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ Connolly, Griffin (August 30, 2018). "Florida's Ron DeSantis Doubles Down on 'Monkey This Up' Comment". Roll Call. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Jacobs, Julia (August 29, 2018). "DeSantis Warns Florida Not to 'Monkey This Up,' and Many Hear a Racist Dog Whistle". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Walters, Joanna (August 29, 2018). "Ron DeSantis tells Florida voters not to 'monkey this up' by choosing Gillum". The Guardian. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Filkins, Dexter (June 18, 2022). "Can Ron DeSantis Displace Donald Trump as the G.O.P.'s Combatant-in-Chief?". The New Yorker (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved June 21, 2022.

DeSantis insisted that there was no racial motive behind the statement — 'He uses a lot of dorky phrases like that,' one of his former colleagues told me — and the outrage didn't endure.

. - ^ "A Frustrated Ron DeSantis Dogged By Questions Of Race", CBS News (September 20, 2018): "DeSantis strongly denied that charge...."

- ^ Wootson, Cleve. "'We Negroes' robocall is an attempt to 'weaponize race' in Florida campaign, Gillum warns", Washington Post (September 2, 2018): "GOP candidate Ron DeSantis denies any racial intent...."

- ^ Sarlin, Benjy. "DeSantis wins Florida governor's race, defeating progressive Andrew Gillum", NBC News (November 6, 2018): "DeSantis denied the charge...."

- ^ "GOP Florida governor nominee Ron DeSantis criticized for "monkey" remark". CBS News. August 29, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

The race between Gillum and DeSantis is widely seen as a toss-up.

- ^ "4 Florida sheriffs, including Brevard County's Wayne Ivey, back Ron DeSantis". Florida Today. October 16, 2018.

- ^ "Thin blue line goes red: Police chiefs backing Ron DeSantis". Florida Politics. October 31, 2018.

- ^ Caputo, Marc. "DeSantis to name Nuñez as Florida's first Cuban-American female running mate". Politico. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ Moe, Alex; Shabad, Rebecca; Vitali, Ali (September 10, 2018). "Amid heated governor's race, Ron DeSantis resigns from Congress". NBC News. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Contorno, Steve. "Morning Joe mocks Ron DeSantis for ducking tough questions on Florida issues". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Kirby. "Florida governor election results: Andrew Gillum versus Ron DeSantis". Tampa Bay Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "Gillum reverses course on conceding Florida governor race". CNBC. November 10, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "With Florida recount over, Andrew Gillum's last chance to become governor rests with the courts". USA Today (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Nam, Rafael (November 15, 2018). "Florida Senate race heads to a hand recount". The Hill (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Dan Merica; Sophie Tatum (November 17, 2018). "Andrew Gillum concedes Florida governor's race to Ron DeSantis". CNN. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Contorno, Steve (November 8, 2021). "Florida Gov. DeSantis officially launches 2022 reelection bid". CNN. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Greenwood, Max (November 8, 2021). "DeSantis officially files paperwork for reelection bid". The Hill. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Miami Herald (via McClatchy), "Feds say $5,000 donation to Florida Gov. Crist is illegal". February 27, 2009 (accessed October 16, 2019)

- ^ Greenlee, Will (November 7, 2022). "Gubernatorial candidate Charlie Crist urges people to vote, criticizes incumbent in SLC". MSN. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Stone, Tyler (November 4, 2022). "Charlie Crist: I'm Pro-Democracy, DeSantis Is One Of The Biggest Threats To Democracy". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Greenwood, Max (October 25, 2022). "DeSantis slams Crist as a 'worn-out, old donkey' in Florida gubernatorial debate". The Hill. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Schemmel, Alec (October 24, 2022). "DeSantis claims Crist only showed up to work for 14 days this year: 'Imagine that deal for you'". The National Desk. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Zac (November 9, 2022). "DeSantis strengthens potential presidential campaign with landslide reelection win". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (November 9, 2022). "Ron DeSantis landslide victory brings Trump and 2024 into focus". The Guardian. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Mahoney, Emily L.; Peace, Lauren (November 8, 2022). "DeSantis wins second term as Florida governor, beating Crist in landslide". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, John (November 9, 2022). "With GOP sweep, Gov. Ron DeSantis says he recast Florida's political map". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Barone, Michael (November 9, 2022). "Trump and Biden big losers, DeSantis big winner in 2022". Washington Examiner. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Man, Anthony; Dusenbury, Wells (November 10, 2022). "DeSantis-led red wave penetrates even once-blue Palm Beach County". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Lo, Dodds (November 8, 2022). "Charlie Crist drowned by Democrat groans as he concedes to Ron DeSantis in Florida". MSN. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Lo, Dodds (November 8, 2022). "DeSantis Delivers Victory Speech After Defeating Crist in Race For Florida Governor". MSN. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ "DeSantis already governor when ceremony begins". Tampa Bay Times.

- ^ Wilson, Sarah (January 11, 2019). "Florida clemency board pardons Groveland Four 70 years later". WFTV 9 ABC. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Davis, Zuri (January 11, 2019). "70 Years After They Were Wrongly Imprisoned, the Groveland Four Have Been Pardoned". Reason.com. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ J. Dudley Goodlette (September 24, 2019). Report and Recommendation of Special Master Archived 2022-12-07 at the Wayback Machine The Florida Senate.

- ^ Patrick, Craig (January 31, 2019). "Florida Gov. DeSantis signs executive order scrapping Common Core". Fox News (from WTVT). Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Forgey, Quint (June 4, 2020). "DeSantis: 'We want to get to yes' on hosting RNC in Florida". Politico. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Shabad, Rebecca; Gregorian, Dareh (June 4, 2020). "Gov. Ron DeSantis says Florida can host Republican National Convention". NBC News. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Garrison, Joey; King, Ledyard (June 13, 2020). "Faced with coronavirus, Republican and Democratic leaders overhaul convention plans". USA Today. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Mazzei, Patricia; Karni, Annie (July 23, 2020). "Trump Abruptly Cancels Republican Convention in Florida: 'It's Not the Right Time'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Swisher, Skyler (April 23, 2021). "DeSantis signs sweeping gambling deal that may bring sports betting to Florida". sun-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Dixon, Matt (April 30, 2021). "'Ron's regime': Florida Republicans give DeSantis what he wants". Politico. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Call, James (April 30, 2021). "It's over. Who won? Who lost? A look back at the 2021 Florida legislative session". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Allan; Caputo, Marc (June 1, 2022). "'Full-throttle': How the Florida Legislature is making Ron DeSantis a GOP juggernaut". NBC News. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Park, Clayton (November 22, 2021). "DeSantis visits Daytona Buc-ee's to announce proposal to waive Florida's gas tax". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Contorno, Steve. ”DeSantis says GOP will not 'mess with Social Security,' as Democrats and Trump slam his past support for privatization”, CNN (March 2, 2023).

- ^ أ ب ت Wootson, Cleve R. Jr.; Stanley-Becker, Isaac; Rozsa, Lori; Dawsey, Josh (July 25, 2020). "Coronavirus ravaged Florida, as Ron DeSantis sidelined scientists and followed Trump". The Washington Post.

- ^ Krischer Goodman, Cindy. "Secrecy and spin: How Florida's governor misled the public on the COVID-19 pandemic". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ "Florida and DeSantis Defy Covid-19 and the Critics". Bloomberg.com. May 21, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Cetoute, Devoun (May 4, 2023). "As COVID begins its fourth year, here's how Florida fared in cases, deaths and vaccines". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Florida's COVID-19 deaths are still among the highest in the nation". WUSF Public Media. October 14, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

When looking at all COVID-19 deaths in the state, the age-adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 has Florida ranked 24th in the nation. The New York Times analysis places Florida's overall death rate as the 10th highest in the nation.

- ^ Lewis, Helen (November 10, 2022). "DeSantis's COVID Gamble Paid Off: Florida's governor turned his coronavirus policies into a parable of American freedom". The Atlantic.

- ^ قالب:Cute web

- ^ Gross, Samantha J (March 11, 2020). "Is there community spread of COVID-19 in Florida? DeSantis tries to clear it up". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus Update: Governor Ron DeSantis Calls For Major Disaster Declaration For Florida". MSN News. March 26, 2020.

- ^ "Gov. Ron DeSantis won't shut down Florida. Here's who he's talking to about that". Tampa Bay Times. March 25, 2020.

- ^ Klas, Mary Ellen; Contorno, Steve (April 1, 2020). "Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis issues statewide stay-at-home order". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, John; Anderson, Zac (June 17, 2020). "Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis pledges to keep state open, downplays rise in coronavirus cases". USA Today.

- ^ Filkins, Dexter (June 18, 2022). "Can Ron DeSantis Displace Donald Trump as the G.O.P.'s Combatant-in-Chief?". The New Yorker (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved June 21, 2022.

the Great Barrington Declaration...argued that many governments were doing more harm than good by shutting down economies and schools. The only practical approach, they said, would be to protect the most vulnerable—mainly by isolating the elderly—and allow everyone else to go about their lives until vaccines and herd immunity neutralized the disease....For DeSantis, who espouses a libertarian vision of small government and personal freedom, the ideas in the Great Barrington Declaration resonated.

. - ^ Stanage, Niall (February 2, 2023). "DeSantis's record on COVID-19: Here's what he said and did". The Hill.

- ^ Rummler, Orion (June 30, 2020). "Florida is 'not going back' on reopening, governor says". Axios (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ DeSantis, Ron (September 25, 2020). "2020-244 Executive Order re: Phase 3; Right to Work; Business Certainty; Suspension of Fines" (PDF). Governor of Florida (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية).

- ^ Calvan, Bobby Caina (September 25, 2020). "Coronavirus: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis reopening state's economy despite COVID-19 spread, bans mask fines". Associated Press.

- ^ "Florida governor extends order suspending COVID-19 related enforcement fines". WESH. November 24, 2020.

- ^ Avlon, John; Warren, Michael; Miller, Brandon (October 29, 2020). "Atlas push to 'slow the testing down' tracks with dramatic decline in one key state". CNN. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ أ ب Klas, Mary Ellen (July 9, 2020). "Gov. Ron DeSantis doubles down on schools reopening full time in August". Tampa Bay Times.

- ^ أ ب Sachs, Sam (August 2022). "Floridians' life expectancy drops by 1.5 years, according to CDC". WFLA-TV.

- ^ أ ب Arias, Elizabeth; Xu, Jiaquan; Tejada-Vera, Betzaida; Murphy, Sherry L.; Bastian, Brigham (August 23, 2022). "U.S. State Life Tables, 2020" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. Atlanta, Georgia: Division of Vital Statistics, Center for Disease Control. 71 (2).

- ^ أ ب Montgomery, Ben (September 6, 2022). "How Florida's life expectancy declined in the pandemic". Axios Tampa Bay.

- ^ "Gov. DeSantis's job approval rating at 54%". Florida Politics – Campaigns & Elections. Lobbying & Government. (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Fineout, Gary (February 1, 2021). "New poll reveals balancing act for DeSantis, Legislature – Publix heiress helped pay for Jan. 6 rally – Florida man Carl Hiassen retiring from Miami Herald". Politico (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Poll: Gov. Ron DeSantis is one of the most popular governors in America". Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Wilner, Michael; Conarck, Ben; Nehamas, Nicholas (February 10, 2021). "White House looks at domestic travel restrictions as COVID mutation surges in Florida". McClatchy. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Montgomery, Ben; Felice, Selene San (February 12, 2021). "New talk of Florida travel restrictions by Biden administration stirs pot". Axios. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Kim, Noah Y. (February 12, 2021). "PolitiFact – No indication that Biden administration is planning to shut down the Florida border". Politifact (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Palma, Bethania (February 13, 2021). "No, Gov. DeSantis Didn't Tell Biden 'Go F— Yourself'". Snopes. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Kruse, Michael (March 18, 2021). "How Ron DeSantis won the pandemic". Politico. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ أ ب Anderson, Zac (April 4, 2021). "'60 Minutes' segment on Florida's COVID vaccine rollout spotlights claims of DeSantis favoring wealthy". Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

- ^ Alfonsi, Sharyn (April 5, 2021). "How the wealthy cut the line during Florida's frenzied vaccine rollout". 60 Minutes.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris. "'60 Minutes' just gave Ron DeSantis a massive gift". CNNdate=April 6, 2021.

- ^ McPhillips, Deidre (April 1, 2021). "Extreme policies, average statistics raise questions around Florida's Covid-19 data". CNN. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (May 3, 2021). "Florida Gov. DeSantis suspends all remaining Covid restrictions: 'We are no longer in a state of emergency'". CNBC (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Governor DeSantis Signs Executive Order Eliminating and Superseding Local COVID-19 Mandates". The National Law Review (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Klas, Mary Ellen (May 4, 2021). "DeSantis declares COVID 'state of emergency' over, overrides local restrictions". Miami Herald.

- ^ Mower, Lawrence; Ross, Allison (May 3, 2021). "DeSantis signs bill banning vaccine 'passports,' suspends local pandemic restrictions". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Call, James (May 3, 2021). "Florida Gov. DeSantis invalidates COVID rules statewide: No need to police people 'at this point'". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ "Florida has more new Covid cases than ever before". NBC News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ "'We're not doing that in Florida': DeSantis says no lockdowns, mask requirements for upcoming school year". WFLA-TV (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). July 23, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "DeSantis signs order withholding state funds from schools with mask mandates". WFLA (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ McDuffie, Will (August 21, 2021). "Florida gives school districts 48 hours to reverse mask mandates or lose funding". ABC News. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Appeals court tosses Florida school mask case". Orlando Weekly. News Service of Florida. December 23, 2021.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (August 2, 2021). "Florida breaks record for COVID-19 hospitalizations". Associated Press. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Jacobson, Louis; Valverde, Miriam (August 6, 2021). "Ron DeSantis' effort to blame COVID-19 spread on migrants is short on evidence". Politifact. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Weissert, Will; Farrington, Brendan (August 6, 2021). "DeSantis feuds with Biden White House as COVID cases rise". Associated Press. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ أ ب Kessler, Glenn (August 6, 2021). "DeSantis's effort to blame Biden for the covid surge in Florida". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 10, 2021.