رسم عصر النهضة الإيطالي

ظلت روما قصبة العالم الفنية. صحيح أن عصر التصوير الروماني العظيم قد انتهى، ولم يعد الآن إيطالي ينافس روبنز أو رمبرانت، ولكن العمارة الرومانية أزهرت، وظل برنيني أشهر فناني أوربا طوال جيل من الزمان. ومع أن بولونيا سطت على زعامة روما في التصوير، فإن نجوم هذه المدرسة كانوا يفدون على روما استكمالا لازدهارهم، وقد وصل فازاري عام 1572 ليرسم الصور الجصية للصالة الملكية في الفاتيكان. واحتشد في »بوتيجي« روما الرسامون الذين ما زالوا محل التبجيل من أقليات مغرمة: ناديو وفديريجو زوكارو، وجيرولامو موتزيانو، وفرانشيسكو دي سالفياتي، وجوفاني لانفرانكو، وبرتولوميو مانفزيدي، ودومنيكو فيتي وأندريا ساكي. وأكثر هؤلاء يصنفون عادة تحت اسم »أصحاب اللازمات« -أي الفنانون المقلدون لطريقة فنان بعينه من أساطين الفن أيام عز النهضة. ويجوز ان نعتبر هذه »اللازمية« (1550-1600) مرحلة أولى للباروك.

أما فيديريجو زوكارو فقد نشر قلوعه فوق أمم أربع. ففي فلورنسة أكمل الصور الجصية التي بدأها فازاري في قبة الكتدرائية، وفي روما رسم »المصلى البولسي« في الفاتيكان، وفي فلاندر صمم سلسلة من الرسوم الهزلية، وفي إنجلترا رسم لوحات مشهورة للملكة إليزابث ولماري ستيوارت، وفي أسبانيا شارك في زخرفة الأسكوريال، وحين عاد إلى روما أنشأ أكاديمية القديس لوقا، التي أوحى نظامها لرينولدز بأكاديمية الفنون الملكية بإنجلترا. وكان الإقبال على فنه أعظم من جميع الرسامين الإيطاليين في ذلك الجيل، ولكن الخلف فضلوا عليه بييترو بيريتيتي كاكورتونا. وبروح الكفايات المتعددة التي أثرت على فناني النهضة صمم بييترو قصري باربريني وبامفيلي بروما، ورسم في قصر بيتي بفلورنسة صوراً جصية تزخر بالأشكال الغريبة في كل غزارة الباروك وتدفقه.

أما القطب الحقيقي للتصوير الروماني في هذا العهد فهو ميكل أنجيلو مريزي دا كارافادجو. كان رجلا فيه روح تشلليني، وقد ولد لبناء بالحجر في لومبارديا، ودرس في ميلان، وانتقل إلى روما واستمتع بعدة مشاجرات، وقتل صديقاً في مبارزة، ثم هرب من السجن، وفر إلى مالطة وقطانيا وسيراقبوز، ومات بضربة شمس على أحد شواطئ صقليو وهو في الرابعة والأربعين (1609)، وفي الفترات التي تخللت هذه المغامرات أحدث ما يشبه الثورة في مزاج التصوير الإيطالي واسلوبه. وقد أحب التناقضات العنيفة بين الضوء والظل، واستخدم حيلا كإضاءة المنظر من مدفأة مخفاة، وشكل صوره بالضوء، وأخرجها من خلفية معتمة، وبدأ في إيطاليا عهد »الفن المعتم« الذي تزعمه جويرتشينو؛ وريبيرا، وسلفاتور روزا. وإذ احتقر عاطفية الرسامين البولونيين المثالية، فقد روع العصر بواقعيته التي أشرفت على الوحشية. كان إذا تناول موضوعاً دينياً يجعل الرسل والقديسين يبدون وكأنهم عمال ضخام غلاظ نقلهم من عمال أرصفة الموانئ. وقد أكسبته لوحة »لاعبي الورق« (المحفوظة بمجموعة روتشيلد بباريس) شهرة دولية. أما لوحة »الموسيقيين«- وهم ثلاثة من المغنيين وعواد جميل-فقد تراكم عليها التراب ثلاثة قرون قبل أن يعثر عليها في متجر للتحف القديمة بشمالي إنجلترا حوالي 1935، وبيعت لجراح بمبلغ مائة جنيه، ثم اشتراها متحف المتروبوليتان بنيويورك (1952) بخمسين ألف دولار. وقد درجت الكنيسة على رفض صور كارافادجو الدينية باعتبارها مسرفة في الابتذال مفتقرة إلى السمو، أما اليوم فهي مشتهى كل ذواقة الفن. وقد بلغ إعجاب روبنز بلوحة هذا الإيطالي المسماة »مادونا ديل روزاريو« مبلغاً حمله على جمع 1.800 جولدن من فناني أنتورب ليشتريها ويهديها إلى كنيسة القديس بولس(85)، ولوحة »عشاء عمواس« (بلندن) لا تبلغ في عمقها نظيرتها التي رسمها رمبرانت، ولكنها تصوير قوي لأشكال الفلاحين. أما »موت العذراء« (المحفوظة باللوفر)- وهي أيضاً صورة ريفية-فكانت إحدى الصور التي وطدت مدرسة »الطبيعيين« في إيطاليا والواقعيين في اسبانيا والأراضي المنخفضة. لقد أكثر كارافادجو من تأكيد ميلودراما العنف والخشونة، ولكن التاريخ كالخطابة قلما يقرر نقطة دون أن يبالغ فيها. وقد أقشعر لمرأى عمال الشحن مفتولي العضل هؤلاء جيل استنفد موضوعات العاطفة، ثم قبلهم على أنهم مدخل منشط دخل به إلى الفن رجال منسيون. والتقط ريبيرا فرشاة كارافادجو القائمة ولحق به، واقتفى رمبرانت أسلوب الإيطالي في توزيع الضوء والظل وجوّده، وحتى مصورو القرن التاسع عشر شعروا بهذا التأثير العاصف.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التأثيرات

The influences upon the development of Renaissance painting in Italy are those that also affected architecture, engineering, philosophy, language, literature, natural sciences, politics, ethics, theology, and other aspects of Italian society during the Renaissance period. The following is a summary of points dealt with more fully in the main articles that are cited above.

الفلسفة

A number of Classical texts, that had been lost to Western European scholars for centuries, became available. These included Philosophy, Poetry, Drama, Science, a thesis on the Arts and Early Christian Theology. The resulting interest in Humanist philosophy meant that man's relationship with humanity, the universe and with God was no longer the exclusive province of the Church. A revived interest in the Classics brought about the first archaeological study of Roman remains by the architect Brunelleschi and sculptor Donatello. The revival of a style of architecture based on classical precedents inspired a corresponding classicism in painting, which manifested itself as early as the 1420s in the paintings of Masaccio and Paolo Uccello.

العلم والتكنولوجيا

Simultaneous with gaining access to the Classical texts, Europe gained access to advanced mathematics which had its provenance in the works of Byzantine and Islamic scholars. The advent of movable type printing in the 15th century meant that ideas could be disseminated easily, and an increasing number of books were written for a broad public. The development of oil paint and its introduction to Italy had lasting effects on the art of painting.

المجتمع

The establishment of the Medici Bank and the subsequent trade it generated brought unprecedented wealth to a single Italian city, Florence. Cosimo de' Medici set a new standard for patronage of the arts, not associated with the church or monarchy. The serendipitous presence within the region of Florence of certain individuals of artistic genius, most notably Giotto, Masaccio, Brunelleschi, Piero della Francesca, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, formed an ethos that supported and encouraged many lesser artists to achieve work of extraordinary quality.[1]

A similar heritage of artistic achievement occurred in Venice through the talented Bellini family, their influential inlaw Mantegna, Giorgione, Titian and Tintoretto.[1][2][3]

الموضوعات

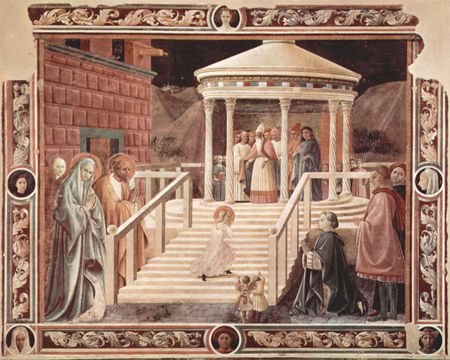

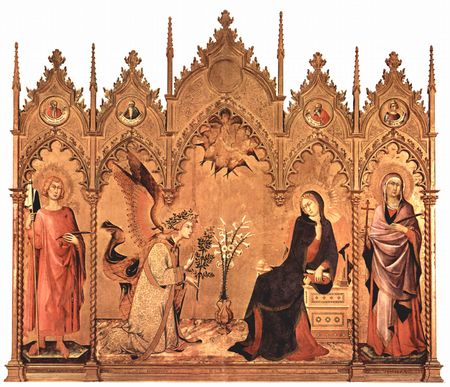

Much painting of the Renaissance period was commissioned by or for the Catholic Church. These works were often of large scale and were frequently cycles painted in fresco of the Life of Christ, the Life of the Virgin or the life of a saint, particularly St. Francis of Assisi. There were also many allegorical paintings on the theme of Salvation and the role of the Church in attaining it. Churches also commissioned altarpieces, which were painted in tempera on panel and later in oil on canvas. Apart from large altarpieces, small devotional pictures were produced in very large numbers, both for churches and for private individuals, the most common theme being the Madonna and Child.

Throughout the period, civic commissions were also important. Local government buildings were decorated with frescoes and other works both secular, such as Ambrogio Lorenzetti's The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, and religious, such as Simone Martini's fresco of the Maestà, in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena.

Portraiture was uncommon in the 14th and early 15th centuries, mostly limited to civic commemorative pictures such as the equestrian portraits of Guidoriccio da Fogliano by Simone Martini, 1327, in Siena and, of the early 15th century, John Hawkwood by Uccello in Florence Cathedral and its companion portraying Niccolò da Tolentino by Andrea del Castagno.

During the 15th century portraiture became common, initially often formalised profile portraits but increasingly three-quarter face, bust-length portraits. Patrons of art works such as altarpieces and fresco cycles often were included in the scenes, a notable example being the inclusion of the Sassetti and Medici families in Domenico Ghirlandaio's cycle in the Sassetti Chapel. Portraiture was to become a major subject for High Renaissance painters such as Raphael and Titian and continue into the Mannerist period in works of artists such as Bronzino.

With the growth of Humanism, artists turned to Classical themes, particularly to fulfill commissions for the decoration of the homes of wealthy patrons, the best known being Botticelli's Birth of Venus for the Medici. Increasingly, Classical themes were also seen as providing suitable allegorical material for civic commissions. Humanism also influenced the manner in which religious themes were depicted, notably on Michelangelo's Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Other motifs were drawn from contemporary life, sometimes with allegorical meaning, some sometimes purely decorative. Incidents important to a particular family might be recorded like those in the Camera degli Sposi that Mantegna painted for the Gonzaga family at Mantua. Increasingly, still lifes and decorative scenes from life were painted, such as the Concert by Lorenzo Costa of about 1490.

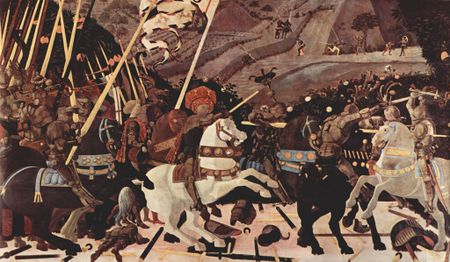

Important events were often recorded or commemorated in paintings such as Uccello's Battle of San Romano, as were important local religious festivals. History and historic characters were often depicted in a way that reflected on current events or on the lives of current people. Portraits were often painted of contemporaries in the guise of characters from history or literature. The writings of Dante, Voragine's Golden Legend and Boccaccio's The Decameron were important sources of themes.

In all these subjects, increasingly, and in the works of almost all painters, certain underlying painterly practices were being developed: the observation of nature, the study of anatomy, of light, and perspective.[1][2][4]

رسم النهضة الأولي

تقاليد الرسم التوسكاني في القرن 13

The art of the region of Tuscany in the late 13th century was dominated by two masters of the Italo-Byzantine style, Cimabue of Florence and Duccio of Siena. Their commissions were mostly religious paintings, several of them being very large altarpieces showing the Madonna and Child. These two painters, with their contemporaries, Guido of Siena, Coppo di Marcovaldo and the mysterious painter upon whose style the school may have been based, the so-called Master of St Bernardino, all worked in a manner that was highly formalised and dependent upon the ancient tradition of icon painting.[5] In these tempera paintings many of the details were rigidly fixed by the subject matter, the precise position of the hands of the Madonna and Christ Child, for example, being dictated by the nature of the blessing that the painting invoked upon the viewer. The angle of the Virgin's head and shoulders, the folds in her veil, and the lines with which her features were defined had all been repeated in countless such paintings. Cimabue and Duccio took steps in the direction of greater naturalism, as did their contemporary, Pietro Cavallini of Rome.[1]

جوتو

Giotto (1266–1337), by tradition a shepherd boy from the hills north of Florence, became Cimabue's apprentice and emerged as the most outstanding painter of his time.[6] Giotto, possibly influenced by Pietro Cavallini and other Roman painters, did not base the figures he painted upon any painterly tradition, but upon the observation of life. Unlike those of his Byzantine contemporaries, Giotto's figures are solidly three-dimensional; they stand squarely on the ground, have discernible anatomy and are clothed in garments with weight and structure. But more than anything, what set Giotto's figures apart from those of his contemporaries are their emotions. In the faces of Giotto's figures are joy, rage, despair, shame, spite and love. The cycle of frescoes of the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin that he painted in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua set a new standard for narrative pictures. His Ognissanti Madonna hangs in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, in the same room as Cimabue's Santa Trinita Madonna and Duccio's Ruccellai Madonna where the stylistic comparisons between the three can easily be made.[7] One of the features apparent in Giotto's work is his observation of naturalistic perspective. He is regarded as the herald of the Renaissance.[8]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

معاصرو جوتو

Giotto had a number of contemporaries who were either trained and influenced by him, or whose observation of nature had led them in a similar direction. Although several of Giotto's pupils assimilated the direction that his work had taken, none was to become as successful as he. Taddeo Gaddi achieved the first large painting of a night scene in an Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Baroncelli Chapel of the Church of Santa Croce, Florence.[1]

The paintings in the Upper Church of the Basilica of St. Francis, Assisi, are examples of naturalistic painting of the period, often ascribed to Giotto himself, but more probably the work of artists surrounding Pietro Cavallini.[8] A late painting by Cimabue in the Lower Church at Assisi, of the Madonna and St. Francis, also clearly shows greater naturalism than his panel paintings and the remains of his earlier frescoes in the upper church.

الموت والخلاص

A common theme in the decoration of Medieval churches was the Last Judgement, which in northern European churches frequently occupies a sculptural space above the west door, but in Italian churches such as Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel it is painted on the inner west wall. The Black Death of 1348 caused its survivors to focus on the need to approach death in a state of penitence and absolution. The inevitability of death, the rewards for the penitent and the penalties of sin were emphasised in a number of frescoes, remarkable for their grim depictions of suffering and their surreal images of the torments of Hell.

These include the Triumph of Death by Giotto's pupil Orcagna, now in a fragmentary state at the Museum of Santa Croce, and the Triumph of Death in the Camposanto Monumentale at Pisa by an unknown painter, perhaps Francesco Traini or Buonamico Buffalmacco who worked on the other three of a series of frescoes on the subject of Salvation. It is unknown exactly when these frescoes were begun but it is generally presumed they post-date 1348.[1]

Two important fresco painters were active in Padua in the late 14th century, Altichiero and Giusto de' Menabuoi. Giusto's masterpiece, the decoration of the Padua Baptistery, follows the theme of humanity's Creation, Downfall, and Salvation, also having a rare Apocalypse cycle in the small chancel. While the whole work is exceptional for its breadth, quality and intact state, the treatment of human emotion is conservative by comparison with that of Altichiero's Crucifixion at the Basilica of Sant'Antonio, also in Padua. Giusto's work relies on formalised gestures, where Altichiero relates the incidents surrounding Christ's death with great human drama and intensity.[9]

In Florence, at the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella, Andrea di Bonaiuto was commissioned to emphasise the role of the Church in the redemptive process, and that of the Dominican Order in particular. His fresco Allegory of the Active and Triumphant Church is remarkable for its depiction of Florence Cathedral, complete with the dome which was not built until the following century.[1]

القوطية العالمية

During the later 14th century, International Gothic was the style that dominated Tuscan painting. It can be seen to an extent in the work of Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, which is marked by a formalized sweetness and grace in the figures, and Late Gothic gracefulness in the draperies. The style is fully developed in the works of Simone Martini and Gentile da Fabriano, which have an elegance and a richness of detail, and an idealised quality not compatible with the starker realities of Giotto's paintings.[1]

In the early 15th century, bridging the gap between International Gothic and the Renaissance are the paintings of Fra Angelico, many of which, being altarpieces in tempera, show the Gothic love of elaboration, gold leaf and brilliant colour. It is in his frescoes at his convent of Sant' Marco that Fra Angelico shows himself the artistic disciple of Giotto. These devotional paintings, which adorn the cells and corridors inhabited by the friars, represent episodes from the life of Jesus, many of them being scenes of the Crucifixion. They are starkly simple, restrained in colour and intense in mood as the artist sought to make spiritual revelations a visual reality.[1][10]

رسم النهضة المبكر

فلورنسا

The earliest truly Renaissance images in Florence date from 1401, although they are not paintings. That year a competition was held amongst seven young artists to select the artist to create a pair of bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery, the oldest remaining church in the city. The competitors were each to design a bronze panel of similar shape and size, representing the Sacrifice of Isaac.

Two of the panels from the competition have survived, those by Lorenzo Ghiberti and Brunelleschi. Each panel shows some strongly classicising motifs indicating the direction that art and philosophy were moving, at that time. Ghiberti used the naked figure of Isaac to create a small sculpture in the Classical style. The figure kneels on a tomb decorated with acanthus scrolls that are also a reference to the art of Ancient Rome. In Brunelleschi's panel, one of the additional figures included in the scene is reminiscent of a well-known Roman bronze figure of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot. Brunelleschi's creation is challenging in its dynamic intensity. Less elegant than Ghiberti's, it is more about human drama and impending tragedy.[11]

Ghiberti won the competition. His first set of Baptistry doors took 27 years to complete, after which he was commissioned to make another. In the total of 50 years that Ghiberti worked on them, the doors provided a training ground for many of the artists of Florence. Being narrative in subject and employing not only skill in arranging figurative compositions but also the burgeoning skill of linear perspective, the doors were to have an enormous influence on the development of Florentine pictorial art.

مصلى برانكاتشي

The first Early Renaissance frescos or paintings were started in 1425 when two artists commenced painting a fresco cycle of the Life of St. Peter in the chapel of the Brancacci family, at the Carmelite Church in Florence. They both were called by the name of Tommaso and were nicknamed Masaccio and Masolino, Slovenly Tom and Little Tom.

More than any other artist, Masaccio recognized the implications in the work of Giotto. He carried forward the practice of painting from nature. His frescos demonstrate an understanding of anatomy, of foreshortening, of linear perspective, of light, and the study of drapery. In the Brancacci Chapel, his Tribute Money fresco has a single vanishing point and uses a strong contrast between light and dark to convey a three-dimensional quality to the work. As well, the figures of Adam and Eve being expelled from Eden, painted on the side of the arch into the chapel, are renowned for their realistic depiction of the human form and of human emotion. They contrast with the gentle and pretty figures painted by Masolino on the opposite side of Adam and Eve receiving the forbidden fruit. The painting of the Brancacci Chapel was left incomplete when Masaccio died at 26 in 1428. The Tribute Money was completed by Masolino while the remainder of the work in the chapel was finished by Filippino Lippi in the 1480s. Masaccio's work became a source of inspiration to many later painters, including Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.[12]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تطور المنظور الخطي

During the first half of the 15th century, the achieving of the effect of realistic space in a painting by the employment of linear perspective was a major preoccupation of many painters, as well as the architects Brunelleschi and Alberti who both theorised about the subject. Brunelleschi is known to have done a number of careful studies of the piazza and octagonal baptistery outside Florence Cathedral and it is thought he aided Masaccio in the creation of his famous trompe-l'œil niche around the Holy Trinity he painted at Santa Maria Novella.[12]

According to Vasari, Paolo Uccello was so obsessed with perspective that he thought of little else and experimented with it in many paintings, the best known being the three The Battle of San Romano paintings (completed by 1450s) which use broken weapons on the ground, and fields on the distant hills to give an impression of perspective.

In the 1450s Piero della Francesca, in paintings such as The Flagellation of Christ, demonstrated his mastery over linear perspective and also over the science of light. Another painting exists, a cityscape, by an unknown artist, perhaps Piero della Francesca, that demonstrates the sort of experiment that Brunelleschi had been making. From this time linear perspective was understood and regularly employed, such as by Perugino in his Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter (1481–82) in the Sistine Chapel.[11]

فهم الضوء

Giotto used tonality to create form. Taddeo Gaddi in his nocturnal scene in the Baroncelli Chapel demonstrated how light could be used to create drama. Paolo Uccello, a hundred years later, experimented with the dramatic effect of light in some of his almost monochrome frescoes. He did a number of these in terra verde ("green earth"), enlivening his compositions with touches of vermilion. The best known is his equestrian portrait of John Hawkwood on the wall of Florence Cathedral. Both here and on the four heads of prophets that he painted around the inner clock face in the cathedral, he used strongly contrasting tones, suggesting that each figure was being lit by a natural light source, as if the source was an actual window in the cathedral.[13]

Piero della Francesca carried his study of light further. In the Flagellation he demonstrates a knowledge of how light is proportionally disseminated from its point of origin. There are two sources of light in this painting, one internal to a building and the other external. Of the internal source, though the light itself is invisible, its position can be calculated with mathematical certainty. Leonardo da Vinci was to carry forward Piero's work on light.[14]

المادونّا

The Virgin Mary, revered by the Catholic Church worldwide, was particularly evoked in Florence, where there was a miraculous image of her on a column in the corn market and where both the Cathedral of "Our Lady of the Flowers" and the large Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella were named in her honour.

The miraculous image in the corn market was destroyed by fire, but replaced with a new image in the 1330s by Bernardo Daddi, set in an elaborately designed and lavishly wrought canopy by Orcagna. The open lower storey of the building was enclosed and dedicated as Orsanmichele.

Depictions of the Madonna and Child were a very popular art form in Florence. They took every shape from small mass-produced terracotta plaques to magnificent altarpieces such as those by Cimabue, Giotto and Masaccio.

In the 15th and first half of the 16th centuries, one workshop more than any other dominated the production of Madonnas. They were the della Robbia family, and they were not painters but modellers in clay. Luca della Robbia, famous for his cantoria gallery at the cathedral, was the first sculptor to use glazed terracotta for large sculptures. Many of the durable works of this family have survived. The skill of the della Robbias, particularly Andrea della Robbia, was to give great naturalism to the babies that they modelled as Jesus, and expressions of great piety and sweetness to the Madonna. They were to set a standard to be emulated by other artists of Florence.

Among those who painted devotional Madonnas during the Early Renaissance are Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Verrocchio and Davide Ghirlandaio. The custom was continued by Botticelli, who produced a series of Madonnas over a period of twenty years for the Medici; Perugino, whose Madonnas and saints are known for their sweetness and Leonardo da Vinci, for whom a number of small attributed Madonnas such as the Benois Madonna have survived. Even Michelangelo, who was primarily a sculptor, was persuaded to paint the Doni Tondo, while for Raphael, they are among his most popular and numerous works.

رسم النهضة المبكر في أجزاء أخرى من إيطاليا

كوزمي تورا في فـِرارا

أوج النهضة

الرعاية والنزعة الإنسانية

التأثير الفلمنكي

التكليفات البابوية

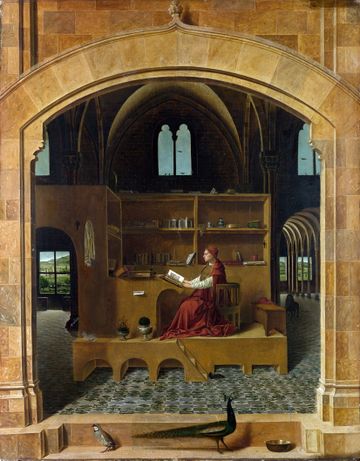

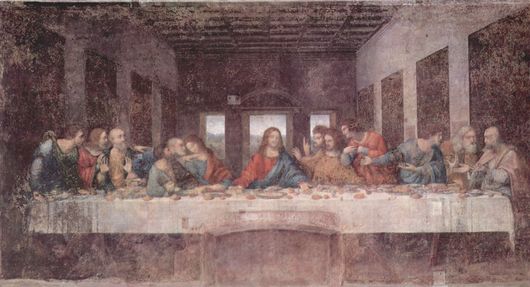

ليوناردو دا ڤنشي

مايكلانجلو

تصوير أوج النهضة في البند

جوڤاني بليني

جورجونه و تيتيان

تأثير تصوير النهضة الإيطالية

أما المعمار فقد شهد مجيء الباروك وذروته. وراح البابوات الواحد تلو الآخر يحيلون عرق المؤمنين الراضين ودراهمهم أمجاداً لروما. فأكمل بيوس الرابع البلفديري وقاعات أخرى في الفاتيكان. وبنى جريجوري الثالث عشر كلية روما وبدأ تشييد قصر الكويرينال-الذي اصبح مسكنا للملك عام 1870. أما دومنيكو فونتانا، الأثير بين المعماريين عند سيكستوس الخامس، فقد صمم قصر اللاتيران الجديد، ومصلى السيستين في كنيسة سانتا ماريا مادجوري، ومقبرة بيوس الخامس في هذا المصلى، وهي باروك مسرف. واضاف الكرادلة والنبلاء خلال ذلك إلى روما قصوراً جديدة (جوستنياني، ولاتشلوتي، وبورجيزي، وباربريني، وروسبليوري)، وفيللات جديدة (بامفيلي، وبورجيزي، ومديتشي). كذلك واصل الهدم أفاعليه، ففي هذه الفترة هدم بولس الخامس حمامات قسطنطين التي عمرت منذ عهد أول الأباطرة دون أن يمسها سوء تقريبا.

وكثر عدد المعماريين الأكفاء، ومنهم جاكومو ديللا بورتا الذي أكمل بكفاية عدة معابد خلفها أساتذة فنيولا ناقصة، كواجهة كنيسة يسوع وقبة كنيسة القديس بطرس، وبهذه الضخامة صمم كابييلا جريجوريانا الفخمة، ولمس قصر فارينزي لمساته الأخيرة، وكان ميكل أنجيلو قد بدأه؛ وهو صاحب الفضل في نافورتين رائعتين تضفيان على روما رواء شباب لا يشيخ. وأبدعهما نافورة السلاحف التي أقامها تاديو لونديني أمام قصر ماتي واشترك مارتينو لونجي الأب مع ديللا بورتا في تشييد قصر الكونسرفاتوري نقلا عن رسوم لميكل أنجيلو، وبدأ هو ذاته قصر بورجيزي، الذي أكمله فلامينو بونتزيو للبابا بولس الخامس. وأسهم دومنيكو فونتانا بنافورة »الفونتانوني« ديل أكوا فيليتشي، وفونتانا ديل أكوا باولينا، وشيد »قاعة البركة« الجميلة على الرواق المعمد الشمالي للاتيران القديس يوحنا. وخلفه أبن أخته كارلو ماديرنا معماريا لكنيسة القديس بطرس، فغير خطتها الأساسية من صليب ميكل أنجيلو اليوناني إلى الصليب اللاتيني، وصمم واجهة هذا الضريح العظيم، ووجد في حمامات كاراكاللا ودقلديانوس إلهاما بصحنها الهائل. وأعاد فرانشسكو بوروميني، تلميذ ماديرنا، بناء مدخل لاتيران القديس يوحنا بناء فاخرا، وبدأ رائعته-كنيسة سانت أجنيس-الفخمة الأنيقة التي تضارع »كنيسة يسوع« في بيانها للباروك الروماني. أما كنيسة يسوع فقد صممها (1568) جاكومودا فنيولا تحقيقا لرغبة اليسوعيين في معمار تروع فخامته العابدين وتلهمهم وتسمو بنفوسهم. وصمم المعماري وخلفاؤه صحنا فسيحا دون اجنحة، فيه الدعامات والسبندلات والتيجان والكرانيش المزخرفة، ثم مذبح مهيب، وقبة مضيئة، وحلية رائعة من الصور والتماثيل والرخام والفضة والذهب. وفي عام 1700 أضاف أندريا ديل بوتزو، وكان هو ذاته يسوعياً، مقبرة القديس اغناطيوس ومذبحه الرائعين. وقد اختلفت نظرة اليسوعيين للحياة عن نظرة غيرهم من رجال الكنيسة الكاثوليكية، وكانت النقيض التام لنظرة البيورتان, فالفن في رأيهم يجب أن يطهر من الحس الدنيوي، ولكن يجب أن يرحب به في تزيين الحياة والإيمان. على أنه لم يكن هناك »أسلوب يسوعي« بعينه. كانت كنيسة يسوع باروكا في الحجر، وكثير من كنائس اليسوعيين لا سيما في ألمانيا كانت باروكا، ولكن كل كنيسة اتبعت الأشكال والأمزجة المحلية والفاشية.

وكان اكمال كنيسة القديس بطرس آخر منجزات الفن الروماني. فقد خلف ميكل أنجيلو نموذجا للقبة، ولكن »الطبلة« وحدها هي التي كانت ممدودة حين ارتقى سيكستوس الخامس كرسي البابوية. وكان قطرها 138 قدما. ولم يجرؤ على تغطية مساحة هائلة كهذه دون دعامات تتخللها سوى بروتولليسكي بفلورنسة. وأحجم المعماريون والمهندسون أمام العمل الذي اقترحه بووناروتي (ميكل أنجيلو)، وشكا رجال المال من أنه سيكلف مليون دوكاتية وجهد عشر سنين. ولكن سيكستوس أمر بالشروع في العمل آملاً أن يحي القداس تحت القبة الجديدة قبل أن يودع الحياة. وتكفل جاكومو ديللا بورتا بالمهمة يساعده فيها دومنيكو فونتانا. وراح ثمانمائة من الرجال يكدحون ليل نهار-فيما عدا الآحاد-من مارس 1589، إلى أن اعلنت روما في 21 مايو 1590، قبل موت الحبر الجريء بثلاثة أشهر، بإن »البابا المقدس سيكستوس الخامس«، قد أتم عقد قبة كنيسة القديس بطرس، لمجده الدائم وخزي أسلافه«(86).

وقد انتقص من وقع منظر القبة، إلا على بعد، واجهة الباروك التي أقامها ماديرنا في 1607-14. اما الكنيسة نفسها فقد كرست نهائيا عام 1626، بعد 174 سنة من البدء بتخطيطها. وفي عام 1633 صب برنيني بالبرونز البلداكينو (أي المظللة) المزوقة فوق »مقبرة القديس بطرس« والمذبح المرتفع. وقد أنقذ النحات العظيم نفسه باحاطة المدخل إلى الضريح بصف اعمدة بيضي هائل (1655-67) أعان على جعل كنيسة القديس بطرس أفخم بناء على وجه الأرض، كما أن قبتها ذروة توجت كل ما بلغه الفن الحديث من انجازات.

تأثير رسم النهضة الإيطالية على العصور اللاحقة

The lives of both Michelangelo and Titian extended well into the second half of the 16th century. Both saw their styles and those of Leonardo, Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini, Antonello da Messina and Raphael adapted by later painters to form a disparate style known as Mannerism, and move steadily towards the great outpouring of imagination and painterly virtuosity of the Baroque period.

The artists who most extended the trends in Titian's large figurative compositions were Tintoretto and Veronese, although Tintoretto is considered by many to be a Mannerist. Rembrandt's knowledge of the works of both Titian and Raphael is apparent in his portraits. The direct influences of Leonardo and Raphael upon their own pupils was to effect generations of artists including Poussin and schools of Classical painters of the 18th and 19th centuries. Antonello da Messina's work had a direct influence on Albrecht Dürer and Martin Schongauer and through the latter's engravings, countless artists. Influence through Schongauer could be found in the German, Dutch and English schools of stained glass makers, extending into the early 20th century.[15]

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling and later The Last Judgment had direct influence on the figurative compositions firstly of Raphael and his pupils and then almost every subsequent 16th-century painter who looked for new and interesting ways to depict the human form. It is possible to trace his style of figurative composition through Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, Bronzino, Parmigianino, Veronese, to el Greco, Carracci, Caravaggio, Rubens, Poussin and Tiepolo to both the Classical and the Romantic painters of the 19th century such as Jacques-Louis David and Delacroix.

Under the influence of the Italian Renaissance painting, many modern academies of art, such as the Royal Academy, were founded, and it was specifically to collect the works of the Italian Renaissance that some of the world's best known art collections, such as the National Gallery, London, were formed.

انظر أيضاً

- Thematic development of Italian Renaissance painting

- عصر النهضة

- Renaissance architecture

- Mannerism

- Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

- Timeline of Italian painters to 1800

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970)

- ^ أ ب Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, (1974)

- ^ Margaret Aston, The Fifteenth Century, the Prospect of Europe, (1979)

- ^ Keith Christiansen, Italian Painting, (1992)

- ^ John White, Duccio, (1979)

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, (1568)

- ^ All three are reproduced and compared at Italian Renaissance painting, development of themes

- ^ أ ب Sarel Eimerl, The World of Giotto, (1967)

- ^ Mgr. Giovanni Foffani, Frescoes by Giusto de' Menabuoi, (1988)

- ^ Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, (1970)

- ^ أ ب R.E. Wolf and R. Millen, Renaissance and Mannerist Art, (1968)

- ^ أ ب Ornella Casazza, Masaccio and the Brancacci Chapel, (1990)

- ^ Annarita Paolieri, Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno, (1991)

- ^ Peter Murray and Pier Luigi Vecchi, Piero della Francesca, (1967)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDD