روكوكو

Ballroom ceiling of the Ca Rezzonico in Venice with illusionistic quadratura painting by Giovanni Battista Crosato (1753); Chest of drawers by Charles Cressent (1730); Kaisersaal of Würzburg Residence by Balthasar Neumann (1749–51) | |

| سنوات النشاط | 1730s to 1760s |

|---|---|

| البلد | France, Italy, Central Europe |

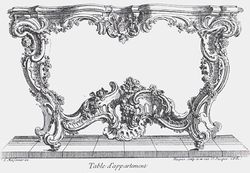

روكوكو ، "Rocaille " وتعني في اللغة الفرنسية هى الصدفة أو المحارة غير المنتظمة الشكل ذات الخطوط المنحنية والتى استمدت منها زخارف في تلك الفترة ويعتبر فن التزين الداخلي. وظهر هذا الطراز من الفن في القرن الثامن عشر ويعد امتدادا للباروك ولكن بمقاييس جمالية تتسم بالسلاسة والرقة. واستمر هذا الطراز مزدهرا في ألمانيا وفرنسا بصفة خاصة واختفى من فرنسا بعد قيام الثورة الفرنسية في عام 1789.

عوامل ظهور طراز الروكوكو

- نظرا أن أوروبا كانت تعيش في حالة من الرخاء ، فانتشرت مظاهر الرفاهية .

- اتساع مجال الحياة الاجتماعية.

بدأ انتشار هذا الطرازفى عام1715 حيث فضل الامراء والنبلاء الاقامة في باريس بدلا من العودة إلى قصورهم العظيمة في الريف، فشيدوا منازل عرفت باسم "لوكاندة" مثل لوكاندة سوبيز وماتينيون ، وبدلا من الاهنمام بالوجهات الارستقراطية التى نشرها ليبران، اهتم النبلاء بزخرفة منازلهم من الداخل. وابتكر المهندسون زخارف استمدوا زخارفها من شكل الصدفة وقد عم هذا الطراز في ميادين التصوير والنحت وفى الاثاث وما شاكله. وبدأ الفن في أن يلعب دوره كمظهر للحياة ويعبر عنها ويجسد ملامحها . ظهر طراز فن الروكوكو بعد أن وصل فن الباروك إلى أقصى درجة ممكنة من الزخرفة خارجالعمائر فبدأ ينعكس عليها من الداخل وبذلك بدأ الاسلوب الجديد في التزيين قصد منه تجميل القصور.

سمات طراز فن الروكوكو

الروكوكو في مختلف الطرق الفنية

في الأثاثات وأدوات الديكور

- كان هدفه الاساسى هو المتعة والترفيه والاستحواذ على استحسان المجتمع الطبقى الجديد. - لقد احتلت المرأة في هذا العصر مكانة عالية في المجتمع وحظيت باهتمام كبير من قبل الفنانين ابتداء من المعمارى إلى الصانع الدقيق فكانوا يسعون إلى رضاها فيصهرون الحياة باكملها ويصغونها من جديد على هواها.

-واتسم طراز هذا الفن بأنه فن ذات طابع دنيوى سقط منه كل ادراك للمقدسات والتحليق فيما وراء الطبيعة . بما فيها الاساطير القديمةرغم انها ظهرت أثارها في التصوير والنحت و لكن اتخذت شكلا دنيويا مسرحيا

- يرجع الفضل في نشأة هذا الطراز الفريد من نوعه في الرقة والاناقة والاسلوب المبتكر الذى ابتدعه المصور " واتو " في أعماله التى تعتبر بمثابة تحول كبير في اسلوب الفن إلى اتجاهه الجديد.

-فن الروكوكو لم يكن فن الملوك، كما كان فن الباروك، وانما كان فن الطبقة الأرستقراطية والطبقة الوسطى الكبيرة. لقد ظهر في عصر الروكوكو اتجاه حسي وجمالي. فقد كان مفرط بعبادته الحسية للجمال، وتميزت لغته الشكلية المتكلفة، والشديدة البراعة، ذات الرشاقة المنغمة. لقد كان اتجاهاً طبيعياً لمجتمع هوائي، وسلبي متعب، يلتمس في الفن لذة وراحة

التصميم الداخلي

الرسم

إيطاليا

Artists in Italy, particularly Venice, also produced an exuberant rococo style. Venetian commodes imitated the curving lines and carved ornament of the French rocaille, but with a particular Venetian variation; the pieces were painted, often with landscapes or flowers or scenes from Guardi or other painters, or Chinoiserie, against a blue or green background, matching the colours of the Venetian school of painters whose work decorated the salons. Notable decorative painters included Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who painted ceilings and murals of both churches and palazzos, and Giovanni Battista Crosato who painted the ballroom ceiling of the Ca Rezzonico in the quadraturo manner, giving the illusion of three dimensions. Tiepelo travelled to Germany with his son during 1752–1754, decorating the ceilings of the Würzburg Residence, one of the major landmarks of the Bavarian rococo. An earlier celebrated Venetian painter was Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, who painted several notable church ceilings. [1]

The Venetian Rococo also featured exceptional glassware, particularly Murano glass, often engraved and coloured, which was exported across Europe. Works included multicolour chandeliers and mirrors with extremely ornate frames. [1]

Ceiling of church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, by Piazzetta (1727)

Juno and Luna by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1735–45)

Murano glass chandelier at the Ca Rezzonico (1758)

- Ca' Rezzonico (Venice) - Ceiling of the Ballroom.jpeg

Ballroom ceiling of the Ca Rezzonico with ceiling by Giovanni Battista Crosato (1753)

جنوب ألمانيا وروسيا

The Rococo decorative style reached its summit in southern Germany and central Europe from the 1730s until the 1770s. It was first introduced from France through the publications and works of French architects and decorators, including the sculptor Claude III Audran, the interior designer Gilles-Marie Oppenordt, the architect Germain Boffrand, the sculptor Jean Mondon, and the draftsman and engraver Pierre Lepautre. Their work had an important influence on the German Rococo style.[2]

Amalienburg pavilion in Munich by François de Cuvilliés (1734–1739)

Hall of Mirrors of Amalienburg by Johann Baptist Zimmermann (1734–1739)

Looking up the central stairway at Augustusburg Palace in Brühl by Balthasar Neumann (1741–1744)

The Wieskirche by Dominikus Zimmermann (1745–1754)

Interior of the Basilica of the Fourteen Holy Helpers by Balthasar Neumann (1743–1772)

The Kaisersaal in the Würzburg Residence by Balthasar Neumann (1749–1751)

Festival Hall of the Schaezlerpalais in Augsburg by Carl Albert von Lespilliez (1765–1770)

Golden Cabinet of the Chinese Palace, Oranienbaum, Russia, built by Antonio Rinaldi for Catherine the Great (1762–1778)

Johann Michael Fischer was the architect of Ottobeuren Abbey (1748–1766), another Bavarian Rococo landmark. The church features, like much of the rococo architecture in Germany, a remarkable contrast between the regularity of the facade and the overabundance of decoration in the interior.[3]

The Russian Empress Catherine the Great was another admirer of the Rococo; The Golden Cabinet of the Chinese Palace in the palace complex of Oranienbaum near Saint Petersburg, designed by the Italian Antonio Rinaldi, is an example of the Russian Rococo.

الرسم

Elements of the Rocaille style appeared in the work of some French painters, including a taste for the picturesque in details; curves and counter-curves; and dissymmetry which replaced the movement of the baroque with exuberance, though the French rocaille never reached the extravagance of the Germanic rococo.[4] The leading proponent was Antoine Watteau, particularly in Pilgrimage on the Isle of Cythera (1717), Louvre, in a genre called Fête Galante depicting scenes of young nobles gathered together to celebrate in a pastoral setting. Watteau died in 1721 at the age of thirty-seven, but his work continued to have influence through the rest of the century. The Pilgrimage to Cythera painting was purchased by Frederick the Great of Prussia in 1752 or 1765 to decorate his palace of Charlottenberg in Berlin.[4]

"Luncheon with Ham" by Nicolas Lancret (1735)

Ceiling of the Salon of Hercules by François Lemoyne (1735)

The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher (1746)

In Austria and Southern Germany, Italian painting had the largest effect on the Rococo style. The Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, assisted by his son, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, was invited to paint frescoes for the Würzburg Residence (1720–1744). The most prominent painter of Bavarian rococo churches was Johann Baptist Zimmermann, who painted the ceiling of the Wieskirche (1745–1754)

Ceiling fresco in the Würzburg Residence (1720–1744) by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Ceiling of the Wieskirche by Johann Baptist Zimmermann (1745–1754)

The Swing, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1767

النحت

The "Veiled Dame (Puritas) by Antonio Corradini (1722)

Cupid by Edmé Bouchardon, National Gallery of Art (1744)

Prometheus by Nicolas-Sébastien Adam (1762)

Vertumnus and Pomone by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1760)

Pygmalion et Galatee by Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1763)

The intoxication of wine by Claude Michel (Clodion), terra-cotta, 1780s-90s

Rococo sculpture was theatrical, colorful and dynamic, giving a sense of movement in every direction. It was most commonly found in the interiors of churches, usually closely integrated with painting and the architecture. Religious sculpture followed the Italian baroque style, as exemplified in the theatrical altarpiece of the Karlskirche in Vienna.

In Italy, Antonio Corradini was among the leading sculptors of the Rococo style. A Venetian, he travelled around Europe, working for Peter the Great in St. Petersburg, for the imperial courts in Austria and Naples. He preferred sentimental themes and made several skilled works of women with faces covered by veils, one of which is now in the Louvre.[5]

Atlantides in the upper Belvedere Palace, Vienna, by Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt (1721-22)

Assumption scene by Egid Quirin Asam (1722-23) former monastery church, Rohr in Niederbayern

El Transparente altar in Toledo Cathedral by Narciso Tomé (1721-32)

Fountain of Neptune and Amphitrite Palace of Versailles, by Lambert-Sigisbert Adam and Nicolas-Sebastien Adam (1740)

Fountain nymphs by Lambert Sigisbert Adam at Sanssouci palace, Prussia (1740s)

الپورسلين

A new form of small-scale sculpture appeared, the porcelain figure, or small group of figures, initially replacing sugar sculptures on grand dining room tables, but soon popular for placing on mantelpieces and furniture. The number of European factories grew steadily through the century, and some made porcelain that the expanding middle classes could afford. The amount of colourful overglaze decoration used on them also increased. They were usually modelled by artists who had trained in sculpture. Common subjects included figures from the commedia dell'arte, city street vendors, lovers and figures in fashionable clothes, and pairs of birds.

Johann Joachim Kändler was the most important modeller of Meissen porcelain, the earliest European factory, which remained the most important until about 1760. The Swiss-born German sculptor Franz Anton Bustelli produced a wide variety of colourful figures for the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory in Bavaria, which were sold throughout Europe. The French sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) followed this example. While also making large-scale works, he became director of the Sevres Porcelain manufactory and produced small-scale works, usually about love and gaiety, for production in series.

The Music Lesson, Chelsea porcelain, Metropolitican Museum (c. 1765)

High altar of the Karlskirche in Vienna (1737)

Cup with saucer; circa 1753; soft-paste porcelain with glaze and enamel; Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Harlequin and Columbine, Capodimonte porcelain, c. 1745

Pair of lovers group of Nymphenburg porcelain, c. 1760, modelled by Franz Anton Bustelli

Figure of a cheese seller by Bustelli, Nymphenburg porcelain (1755)

العمارة

بدأ انتشار هذا الطراز في عام 1715 حيث فضل الامراء والنبلاء الاقامة في باريس بدلا من العودة إلى قصورهم العظيمة في الريف، فشيدوا منازل عرفت باسم " لوكاندة" مثل لوكاندة سوبيز وماتينيون ، وبدلا من الاهنمام بالوجهات الارستقراطية التى نشرها ليبران، اهتم النبلاء بزخرفة منازلهم من الداخل. وابتكر المهندسون زخارف استمدوازخارفها من شكل الصدفة وقد عم هذا الطراز في ميادين التصوير والنحت وفى الاثاث وما شاكله.

التصوير

اهتمام المصورين في تلك الفتره موجه إلى رسم موضوعات تصورحياة المجتمعات الارستقراطية بحفلاتها او موضوعات تدور حول المرأة وكان واتوه هو الراعى بالنسبة لهذه الموضوعات، واتبع اسلوبه عددا كبيرا من المصورين أشهرهم بوشيه وفراجونار.

معرض الصور

العمارة

Church of Saint Francis of Assisi (Ouro Preto) in São João del Rei, 1749–1774, by the Brazilian master Aleijadinho

Czapski Palace in Warsaw, 1712–1721, reflects rococo's fascinations of oriental architecture

St. Andrew's Church in Kiev, 1744–1767, designed by Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli

Zwinger in Dresden

Eszterháza in Fertőd, Hungary, 1720–1766, sometimes called the "Hungarian Versailles"

The Rococo Branicki Palace in Białystok, sometimes referred to as the "Polish Versailles"

Electoral Palace of Trier

Basilica and Convent of Santo Domingo in Lima, Peru, completed in 1766

النقش

الرسم

Antoine Watteau, Pierrot, 1718–1719

Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera , 1718–1721

Jean-Baptiste van Loo, The Triumph of Galatea, 1720

- FdeTroyLectureMoliere.jpg

Jean François de Troy, A Reading of Molière, 1728

Francis Hayman, Dancing Milkmaids, 1735

Charles-André van Loo, Halt to the Hunt, 1737

Gustaf Lundberg, Portrait of François Boucher, 1741

François Boucher, Diana Leaving the Bath, 1742

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Full-length portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1748–1755

François Boucher Portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1756

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Inspiration, 1769

Jean-Honoré Fragonard The Meeting (Part of the Progress of Love series), 1771

Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Marie Antoinette à la Rose, 1783

رسم عصر الروكوكو

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Glass Flask and Fruit, c. 1750

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Spoiled Child, c. 1765

Joshua Reynolds, Robert Clive and his family with an Indian maid, 1765

Angelica Kauffman, Portrait of David Garrick, c. 1765

Louis-Michel van Loo, Portrait of Denis Diderot, 1767

انظر أيضاً

- الروكوكو في البرتغال

- Queluz National Palace

- حركة ثقافية

- كاتدرائية موريكا

- Gilded woodcarving

- تاريخ الرسم

الهامش

- ^ أ ب de Morant 1970.

- ^ De Morant, Henry, Histoire des arts décoratifs (1977), pp. 354–355

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDemartini 2006 pp. 222 - ^ أ ب Cabanne 1988.

- ^ Duby, Georges and Daval, Jean-Luc, La Sculpture de l'Antiquité au XXe Siècle, (2013) pp. 781-832

وصلات خارجية

- Examples

- Rococo in the "History of Art"

- "Rococo Style Guide". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

قراءات اضافية

- Fiske Kimball, 1943. Creation of the Rococo (Reprinted as The Creation of the Rococo Decorative Style, 1980).

- Arno Schönberger and Halldor Soehner, 1960. The Age of Rococo Published in the US as The Rococo Age: Art and Civilization of the 18th Century (Originally published in German, 1959).

- Michael Levey, 1980. Painting in Eighteenth-Century Venice, (Revised edition).

- Pal Kelemen, 1967. Baroque and Rococo in Latin America, (2nd edition).