بنديكت الثالث عشر، بابا أفنيون

| Antipope Benedict XIII | |

|---|---|

| Pope Luna | |

| |

| Papacy began | 11 October 1394 |

| انتهت بابويته | 23 May 1423 |

| سبقه |

|

| خلفه |

|

| يعارض | Roman claimants:

|

| التكريس | 3 October 1394 |

| الترسيم | 11 October 1394 |

| أصبح كاردينال | 20 December 1375 |

| الرتبة | Cardinal-Deacon |

| غيرهم | Cardinal-Deacon of Santa Maria in Cosmedin |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| اسم الميلاد | Pedro Martínez de Luna y Pérez de Gotor |

| وُلِد | 25 نوفمبر 1328 Illueca, Crown of Aragon |

| توفي | 23 مايو 1423 (aged 94) Peniscola, Crown of Aragon |

| دُفِن | Castillo Palacio del Papa Luna, Illueca (skull) |

| الوظيفة | Professor |

| المهنة | Canon law |

| الجامعة الأم | University of Montpellier |

| پاپوات آخرون اسمهم Benedict | |

Pedro Martínez de Luna y Pérez de Gotor (25 November 1328 – 23 May 1423), known as el Papa Luna (حرفياً 'the Moon Pope') or Pope Luna, was an Aragonese nobleman who was christened antipope Benedict XIII during the Western Schism.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Early life

Pedro Martínez de Luna was born at Illueca, Kingdom of Aragon (part of modern Spain), in 1328. He belonged to the de Luna family, who were part of the Aragonese nobility. He studied law at the University of Montpellier, where he obtained his doctorate and later taught canon law. His knowledge of canon law, noble lineage, and austere way of life won him the approval of Pope Gregory XI, who appointed de Luna to the position of Cardinal Deacon of Santa Maria in Cosmedin on 20 December 1375.[1]

Avignon election

In 1377, Pedro de Luna and the other cardinals returned to Rome with Pope Gregory, who had been persuaded to leave his papal base at Avignon.[2] After Gregory's death on 27 March 1378, the people of Rome feared that the cardinals would elect a French pope and return the papacy to Avignon. Consequently, they rioted and laid siege to the cardinals, insisting on an Italian pope. The conclave duly elected Bartolomeo Prignano, Archbishop of Bari, as Urban VI on 9 April, but the new pope proved to be intractably hostile to the cardinals. Some of them reconvened at Fondi in September 1378, declared the earlier election invalid and elected Robert of Geneva as their new pope, initiating the Western Schism. Robert assumed the name Clement VII and moved back to Avignon.[1]

Clement VII sent de Luna as legate to Spain for the Kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Navarre, and Portugal, in order to win them over to the obedience of the Avignon pope. Owing to his powerful relations, his influence in the Province of Aragon was very great. In 1393, Clement VII appointed him legate to France, Brabant, Flanders, Scotland, England, and Ireland. As such he stayed principally in Paris, but he did not confine his activities to those countries that belonged to the Avignon obedience.[1] Following Clement's death on 16 September 1394, the cardinals met at Avignon. The conclave consisted of 11 French cardinals, eight Italians, four Spaniards, and one from Savoy, all proclaiming the ardent wish to reunite the church. The cardinals then elected Luna as the new pope, on the condition that he should labor to quell the schism, and should resign the papal dignity whenever the pope of Rome should do the same, or the college of cardinals demand it.

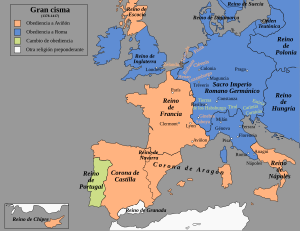

On the death of Urban VI in 1389, the Roman College of Cardinals had chosen Boniface IX; the election of Benedict therefore perpetuated the Western Schism. At the start of his term of office, de Luna was recognised as pope by France, Scotland, Sicily, Castile, Aragon and Navarre. In 1396, Benedict sent Sanchez Muñoz, one of the most loyal members of the Avignon curia, as an envoy to the Bishop of Valencia to bolster support for the Avignon papacy in the Crown of Aragon.

Avignon papacy

In 1398, the Kingdom of France withdrew its recognition of the Avignon anti-popes.[3] Benedict was abandoned by 17 of his cardinals, with only five remaining faithful to him. Benedict's rationale for continuing the rivalry lay in the fact that he was the last living cardinal created by Gregory XI, the last undoubted pope. As the only unquestioned cardinal, Benedict argued, he was, by right and by canon law, the only qualified candidate left who could validly claim the papacy. Following the Council of Constance Benedict's logic was not widely accepted.

An army led by Geoffrey Boucicaut, brother of Jean Boucicaut, occupied Avignon and started a five-year siege of the Papal Palace which ended when Benedict managed to escape from Avignon on 12 March 1403. He sought shelter in the territory of Louis II of Anjou. Avignon immediately submitted again to him, and his cardinals likewise recognized him. Popular sentiment being again in his favor, he was recognized as the legitimate pope by France, Scotland, Castile and Sicily.

After the Roman Pope Innocent VII died in 1406, the newly elected Roman pope, Gregory XII, started negotiations with Benedict, suggesting that they both resign so a new pope could be elected to reunite the Catholic Church. When these talks ended in stalemate in 1408, Charles VI of France declared that his kingdom was neutral to both papal contenders. Charles helped to organise the Council of Pisa in 1409. This council was supposed to arrange for both Gregory and Benedict to resign, so that a new universally recognised pope could be elected. To oppose this, Benedict convoked the Council of Perpignan but with little success. Since both Benedict and Gregory refused to abdicate, the only achievement in Pisa was that a third candidate to the Holy See was put forward: Peter Philarghi, who assumed the name Alexander V.[4]

University of St Andrews

A group of Augustinian clergy, driven from the University of Paris by the Schism and from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge by the Anglo-Scottish Wars, formed a society of higher learning in St Andrews, Fife, Scotland in 1410. The Bishop of St Andrews, Henry Wardlaw, then successfully petitioned Benedict to grant the school university status by issuing a series of papal bulls, which followed on 28 August 1413.[5] Having lost the support of France and driven out from Avignon, Benedict by then had taken refuge in Perpignan, on the Catalan border of the Crown of Aragon, but Scotland was among the handful of supporters that remained loyal. Nowadays, the University of St Andrews's coat of arms/emblem still incorporates that of Benedict.

Etsi doctoribus gentium

In part to bolster faltering support for his papacy, Benedict initiated the year-long Disputation of Tortosa in 1413, which became the most prominent Christian–Jewish disputation of the Middle Ages.[6] Two years later Benedict issued the papal bull Etsi doctoribus gentium which was one of the most complete collections of anti-Jewish laws.[7] Synagogues were closed, Jewish goldsmiths were forbidden to produce Christian sacred objects such as chalices and crucifixes[8] and Jewish book binders were forbidden to bind books which included the names of Jesus or Mary.[9] Those laws were repealed by Pope Martin V, after he received a mission of Jews, sent by the famous synod convoked by the Jews in Forlì, in 1418.

Council of Constance

In 1415, the Council of Constance brought this clash between papal claimants to an end. Gregory XII agreed to resign, and Baldassare Cossa, who had succeeded Philarghi as the Pisan papal contender in 1410 and had assumed the name John XXIII, tried to flee and was deposed during his absence, being subsequently tried upon his return. Benedict, on the other hand, refused to stand down.

Finally, Emperor Sigismund organised a European summit in Perpignan, to convince Benedict to resign his office and end the Western Schism. On 20 September 1415, the Emperor met with Benedict at the Palace of the Kings of Majorca, accompanied by King Ferdinand I of Aragon, delegates of the counts of Foix, Provence, Savoy, and Lorraine, embassies from the kings of France, England, Hungary, Castile, and Navarre, and the Church's representative at the Council of Constance. Benedict still refused to resign, clashing with the Emperor, who left Perpignan on 5 November.[10]

Because of this stubbornness, the Council of Constance declared Benedict a schismatic and excommunicated him from the Catholic Church on 27 July 1417, and elected Martin V as the new consensual pope on 11 November 1417. Benedict, who had lived in Perpignan from 1408 to 1417, now fled to the Peniscola Castle, near Tortosa, in the Kingdom of Aragon. He still considered himself the true Pope. His claim was now only recognised in the Kingdom of Aragon, where he was given protection by King Alfonso V. Benedict remained at Peñíscola from 1417 until his death there on 23 May 1423.[4]

Succession

The day before his death, Benedict appointed four cardinals of proven loyalty to ensure the succession of another pope who would remain faithful to the now beleaguered Avignon line. Three of these cardinals met on 10 June 1423 and elected Sanchez Muñoz as their new pope, with Muñoz assuming the papal name of Clement VIII, whose claim was still recognised by Aragon. The fourth cardinal, Jean Carrier, the archdeacon of Rodez near Toulouse, was absent at this conclave and disputed its validity, whereupon Carrier, acting as a sort of one man College of Cardinals, proceeded to elect Bernard Garnier, the sacristan of Rodez, as pope. Garnier took the name Benedict XIV,[11] but he would never get any importance.

When, in 1429, an agreement between Rome and Aragon was reached, Clement VIII abdicated in favour of recognising Pope Martin V, terminating the Avignon line of anti-popes. In return, he was appointed as bishop of Majorca.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Burials

Benedict XIII was buried in Peniscola castle. His body was later moved to Illueca; but during the War of the Spanish Succession his remains were destroyed. Only his skull was saved, and it was kept in the palace of the Counts of Argillo in Sabiñán. Aragon, Spain. In April 2000, it was stolen from the now ruined palace. The thieves sent an anonymous letter to the mayor of Illueca asking for 1٬000٬000 ( €6٬000). The Spanish Civil Guard found that they were two brothers who were sentenced in November 2006 to 6 months in prison, substituted with €2٬190.[12] The skull was recovered in September 2000. After an anthropological survey, it was placed in the Zaragoza Museum, where it is not in exhibition.[13]

Attempted rehabilitation

On 21 December 2018, the association "Friends of Pope Luna" presented to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith a petition to have Benedict recognised as a legitimate pontiff.[14][15]

See also

| Benedictus XIII (antipope)

]].- Papal selection before 1059

- Papal conclave (since 1274)

Notes

- ^ أ ب ت Kirsch, Johann Peter. "Pedro de Luna." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 2 January 2016

- ^ The pope was repeatedly urged by Catherine of Siena: McGinn, Bernard The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism, (Herder & Herder, 2012), p. 561. Other considerations were the repeated embassies sent by the Roman people, and the war of Florence against the cities of the Papal States.

- ^ McBrien, Richard P., Lives of the Popes, (HarperCollins, 1997), p. 250.

- ^ أ ب Brusher, Rev. Joseph Stanislaus (1980) [1959 Van Nostrand]. "The Great Schism". Popes through the Ages (3rd ed.). Neff-Kane. ISBN 978-0-89141-110-9.

- ^ Great Britain. Commission for Visiting the Universities and Colleges of Scotland (1837). University of St. Andrews. W. Clowes and Sons. pp. 173–.

- ^ Beinart, Haim (2008). "Tortosa, Disputation of". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Grayzel, Solomon (2008). "Bulls, Papal". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Wasserman, Henry (2008). "Goldsmiths and Silversmiths". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Ansbacher, B. Mordechai (2008). "Books". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ قالب:66 PHPC

- ^ Pham, John-Peter. Heirs to the Fisherman: Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. 331-332.

- ^ "El robo del cráneo del Papa Luna se queda en una multa". El Periódico de Aragón (in الإسبانية). 2006-11-07. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Campo, Ramón J. "El cráneo del Papa Luna: historia de un robo | Reportaje especial en Heraldo.es". www.heraldo.es (in الإسبانية). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ La rehabilitación del Papa Luna. https://www.lasprovincias.es/comunitat/rehabilitacion-papa-luna-20190211232314-ntvo.html

- ^ Allen Jr., John L. "Push to rehabilitate past pope illustrates great truth about the present". Archived from the original on 2019-02-12.

Accounts of his life

The Anti-pope (Peter de Luna, 1342–1423): A study in obstinacy by Alec Glasfurd, Roy Publishers, New York (1965) B0007IVH1Q is a somewhat fictionalised or imaginative account of his life.

Pluja seca by Jaume Cabré (2001) is a play based on his death and succession.

L'Anneau du pêcheur ("The Ring of the Fisherman"— a play on the words pêcheur, meaning fisherman, and pécheur, meaning sinner) is a 1995 novel by the French writer Jean Raspail. The narrative has two timelines: the time of Benedict XIII, the last antipope of the Avignon Papacy, and contemporary times, when the Catholic Church tries to discover Benedict's successor, as it turns out that his line of papacy has continued in secret throughout the centuries. The book received the Prix Maison de la Presse and the Prince Pierre Foundation's Literary Prize.[بحاجة لمصدر]

References

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chow, Gabriel. "Antipope Benedict XIII (1394–1423)". GCatholic.org. Toronto. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Hughes, Philip E. (1 January 1947). A History of the Church:Volume 3: The Revolt Against the Church: Aquinas to Luther. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7220-7983-6.

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2018

- Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from The American Cyclopaedia

- Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from The American Cyclopaedia with a Wikisource reference

- Articles incorporating a citation from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- Pages with single-entry sister bar

- Pages using Sister project links with hidden wikidata

- 1328 births

- 1423 deaths

- 14th-century antipopes

- 14th-century Aragonese Roman Catholic priests

- 15th-century antipopes

- 15th-century Aragonese Roman Catholic priests

- Antipopes

- Avignon Papacy

- Bishops of Carpentras

- People from the Province of Zaragoza

- Western Schism

- Victims of body snatching