مولبدنم

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| صفات عامة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الإسم, الرقم, الرمز | موليبدنوم, Mo, 42 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سلاسل كيميائية | transition metals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المجموعة, الدورة, المستوى الفرعي | d , 5 , 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المظهر | معدني رمادي

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| كتلة ذرية | 95.94(2) g/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| شكل إلكتروني | [Kr] 4d5 5s1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| عدد الإلكترونات لكل مستوى | 2, 8, 18, 13, 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| خواص فيزيائية | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحالة | صلب | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| كثافة عندح.غ. | 10.28 ج/سم³ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| كثافة السائل عند m.p. | 9.33 ج/سم³ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نقطة الإنصهار | 2896 ك 2623 م ° 4753 ف ° | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نقطة الغليان | 4912 ك 4639 م ° 8382 ف ° | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حرارة الإنصهار | kJ/mol 37.48 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حرارة التبخر | kJ/mol 617 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| السعة الحرارية | (25 24.06 C (م) ° ( J/(mol·K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الخواص الذرية | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| البنية البللورية | cubic body centered | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حالة التأكسد | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (الأكسيد شديد الحامضية) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سالبية كهربية | 2.16 (مقياس باولنج) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| طاقة التأين (المزيد) |

1st: 684.3 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 1560 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 2618 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف قطر ذري | 145 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف قطر ذري (حسابيا) | 190 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف القطر التساهمي | 145 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| متفرقة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الترتيب المغناطيسي | no data | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| مقاومة كهربية | 20 °C 53.4 nΩ·m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| توصيل حراري | (300 K ك ) 138 (W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تمدد حراري | (25 °C) 4.8 µm/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سرعة الصوت (قضيب رفيع) | (ح.غ.) 5400 م/ث | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| معامل يونج | 329 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| معامل القص | 20 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| معاير الحجم | 230 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نسبة بواسون | 0.31 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| صلابة موس | 5.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم فيكرز للصلادة | 1530 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم برينل للصلادة | 1500 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم التسجيل | 7439-98-7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| النظائر المهمة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المراجع | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

المولِبدنوم أو المولبدن molybdenum عنصر كيميائي في الجدول الدوري. رمزه هو: "Mo" ووزنه الذري 42.

الموليبدنوم عنصر كيميائي وفلز صلب أبيض فضي رمزه الكيميائي Mo. ودرجة انصهاره العالية التي تصل إلى 2,617°م تجعله واحدًا من أقوى وأكثر الفلزات المقاومة للصهر استخدامًا. وعند سبكه (مزجه) مع الفولاذ، يعطي المولبدنوم الفلز قوة وصلابة، خصوصًا عند درجات الحرارة المرتفعة، كما أنه يزيد أيضًا المقاومة الحرارية والكيميائية لفلزات معينة ذات أساس نيكلي عندما يخلط معها.

يقع في الفصيلة VI B (أو 6)؛ أي في فصيلة الكروم التي تحوي إضافة إلى الكروم والمولبدن والتنگستن، العنصرَ ذا العدد الذري 106؛ ويدعى سيبورگيوم Sg. بنيته الإلكترونية 2-8-18-13-1؛ أي يحوي إلكتروناً واحداً بالمدار s5S وخمسة إلكترونات بالمدار d4d. فهو يأخذ نظرياً حسب بنيته أعداد الأكسدة من +1 إلى +6 إلا أن أعداد الأكسدة المعروفة له +3 و+5 و+6، عدده الذري 42، كتلته الحجمية 10.3غ/سم³، نقطة انصهاره 2610 ْس، ونقطة غليانه 5560 ْس، نصف قطر ذرته 1.39 أنگستروم.

يستخدم الموليبدنم في صناعة أجزاء الطائرات والصواريخ، كما أنه عنصر مهم في التغذية النباتية. ولمركبات الموليبدنوم استخدامات صناعية كثيرة، خصوصًا مادة مساعدة (حفّازة) في تكرير النفط، بالإضافة إلى استخدام كبريتيد المولبدنوم للتشحيم مخففًا للاحتكاك عند درجة حرارة عالية تحت ظروف تتحلل فيها أغلب الزيوت. ويستخدم أكسيد المولبدنم في صناعة الفولاذ الذي لا يصدأ لصنع عُدد الورش.

يوجد المولبدنوم في معدن المولبدنيت وبعض المعادن الأخرى. اكتشف هذا العنصر الكيميائي السويدي كارل ولهلم شيل عام 1778م. والعدد الذري للمولبدنوم 42 ووزنه الذري 95,94 ودرجة غليانه 4,612°م.

المركبات

Molybdenum forms chemical compounds in oxidation states −4 and from −2 to +6. Higher oxidation states are more relevant to its terrestrial occurrence and its biological roles, mid-level oxidation states are often associated with metal clusters, and very low oxidation states are typically associated with organomolybdenum compounds. The chemistry of molybdenum and tungsten show strong similarities. The relative rarity of molybdenum(III), for example, contrasts with the pervasiveness of the chromium(III) compounds. The highest oxidation state is seen in molybdenum(VI) oxide (MoO3), whereas the normal sulfur compound is molybdenum disulfide MoS2.[1]

| حالات أكسدة المولبدنم.[2] | |

|---|---|

| −2 | Na 2[Mo 2(CO) 10] |

| 0 | Mo(CO) 6 |

| +1 | Na[C 6H 6Mo] |

| +2 | MoCl 2 |

| +3 | Na 3[Mo(CN)] 6 |

| +4 | MoS 2 |

| +5 | MoCl 5 |

| +6 | MoF 6 |

From the perspective of commerce, the most important compounds are molybdenum disulfide (MoS 2) and molybdenum trioxide (MoO 3). The black disulfide is the main mineral. It is roasted in air to give the trioxide:[1]

- 2 MoS 2 + 7 O 2 → 2 MoO 3 + 4 SO 2

The trioxide, which is volatile at high temperatures, is the precursor to virtually all other Mo compounds as well as alloys. Molybdenum has several oxidation states, the most stable being +4 and +6 (bolded in the table at left).

Molybdenum(VI) oxide is soluble in strong alkaline water, forming molybdates (MoO42−). Molybdates are weaker oxidants than chromates. They tend to form structurally complex oxyanions by condensation at lower pH values, such as [Mo7O24]6− and [Mo8O26]4−. Polymolybdates can incorporate other ions, forming polyoxometalates.[3] The dark-blue phosphorus-containing heteropolymolybdate P[Mo12O40]3− is used for the spectroscopic detection of phosphorus.[4]

The broad range of oxidation states of molybdenum is reflected in various molybdenum chlorides:[1]

- Molybdenum(II) chloride MoCl2, which exists as the hexamer Mo6Cl12 and the related dianion [Mo6Cl14]2-.

- Molybdenum(III) chloride MoCl3, a dark red solid, which converts to the anion trianionic complex [MoCl6]3-.

- Molybdenum(IV) chloride MoCl4, a black solid, which adopts a polymeric structure.

- Molybdenum(V) chloride MoCl5 dark green solid, which adopts a dimeric structure.

- Molybdenum(VI) chloride MoCl6 is a black solid, which is monomeric and slowly decomposes to MoCl5 and Cl2 at room temperature.[5]

The accessibility of these oxidation states depends quite strongly on the halide counterion: although molybdenum(VI) fluoride is stable, molybdenum does not form a stable hexachloride, pentabromide, or tetraiodide.[6]

Like chromium and some other transition metals, molybdenum forms quadruple bonds, such as in Mo2(CH3COO)4 and [Mo2Cl8]4−.[1][7] The Lewis acid properties of the butyrate and perfluorobutyrate dimers, Mo2(O2CR)4 and Rh2(O2CR) 4, have been reported.[8]

The oxidation state 0 and lower are possible with carbon monoxide as ligand, such as in molybdenum hexacarbonyl, Mo(CO)6.[1][9]

الأكاسيد

مقالة مفصلة: أكسيد المولبدنم

مقالة مفصلة: أكسيد المولبدنم

يعرف للمولبدن عدة أكاسيد؛ هي MoO2, Mo2O5 , Mo2O3. وأهم هذه الأكاسيد ثلاثي أكسيد المولبدن MoO3، يحصل عليه بتسخين المعدن في الهواء عند درجة حرارة عالية أو بحرق المركّبات الموافقة للتكافؤ(6)؛ وهو ذو لون أبيض. وهو ثابت، ولا يتفكك بالحرارة، وينحلّ بصعوبة بالمـاء، وينحلّ بالقلويات؛ لكي يؤلّف المولبدات ذات الصيغة العـامة M12MoO4 . ويمكن عدّه بلا مـاء حمض المولبدن H2MoO4. ويحضر هذا الحمض على شكل راسب هلامي بإضافة HNO3 إلى محاليل أملاح المولبدات. غير أن صيغة الراسب الناتج مرتبطة بدرجة الحرارة وحموضة وسط التفاعل. ففي محاليل المولبدات توجد إضافة إلى الأيونات MoO2-4 أيونات كثيرات المولبدات، مثل [HMo6O2]5- و[Mo8O26]4- وغيرها. والصيغة العامة لكثيرات حموض المولبدن XMoO3.YH2O. وكثيرات المولبدات هي MoO3.YH2O.ZA2O حيث A معدن أحادي التكافؤ أو أيون الأمونيوم.

أزرق المولبدن

مقالة مفصلة: أزرق المولبدنم

مقالة مفصلة: أزرق المولبدنم

تعرف هذه المادة باسم الأكسيد الأزرق؛ وهي أكسيد المولبدن التي يبلغ فيها تكافؤ المعدن بين (+5) و(+6). ويحصل عليه بالحالة الغروية بتفاعل بعض المواد المرجعة، مثل H2S,Zn,SO2,SnCl2 مع محاليل حموض المولبدن أو مع المحاليل الحمضية للمولبدات، فيحدث إرجاع جزئي للمعدن من التكافؤ (6) إلى التكافؤ (5). ومن الصيغ التي ترمز إلى هذه المادة: Mo4O11.H2O, Mo2O5.H2O, Mo9O23.8H2O وغيرها.

يستعمل تفاعل تشكل أزرق المولبدن للكشف عن المولبدن في محاليل مركباته. وهو يمتَص بسهولة على سطح الأنسجة النباتية والحيوانية، فيستعمل في صباغة الشعر والفرو والحرير والريش.

برونز المولبدنم

مقالة مفصلة: برونز المولبدنم

مقالة مفصلة: برونز المولبدنم

ينتج برونز المولبدن من إرجاع مولبدات معدن قلوي ما الممزوجة بمصهور الأكسيد MoO3 بالطريقة الكهربائية، فيحصل إضافة إلى MoO2 على مادة لها لون أحمر أو أزرق حسب شروط التحضير ونسبة المعدن القلوي. وصيغة البرونز الأحمر K26Mo1O3؛ وهي من أنصاف النواقل.

مركبات المولبدنم الأخرى ومعقداته

يؤلّف المولبدن عدة مركّبات مع الكبريت هي Mo2S3, MoS2, Mo2S5, MoS3, MoS4. ويؤلّف أيضاً مع الهالوجينات مركّبات عديدة، أكثرها ملون، وأهمها MoCl3, MoCl5, MoF6.

وتعرف للمولبدن - مثل باقي الفلزات الانتقالية - معقّدات عديدة يكون فيها المعدن بدرجة أكـسدة (+5) أو(+6)، ويرتبط فيها مباشرة بذرة أكسـجين واحدة على الأقل. مثال ذلك (MoOF2)5- و(MoO2Cl4)2- و[MoOF4]2-؛ ولكن أهم معقدات المولبدن (MoOCl5)2- الذي يستعمل في تحضير معظم مركّبات المولبدنم (V). ويمكن عزل هذا المعقد على شكل ملح، مثل K2(MoOCl5) الذي ينتج من إضافة KCl إلى محلول MoCl5 في حمض HCl المركز كما أمكن أيضاً تحضير أملاح هذا الأيون المعقد بمعالجة MoCl5 بكلوريد رباعي ألكيل الأمونيوم في وسط من ثنائي أكسيد الكبريت:

ويؤلّف المولبدن معقدات أخرى، مثل Mo(CO)6 الذي يستعمل مادة حافزة مهمة، و[Mo(CN)8]4- وغيرها.

التاريخ

Molybdenite—the principal ore from which molybdenum is now extracted—was previously known as molybdena. Molybdena was confused with and often utilized as though it were graphite. Like graphite, molybdenite can be used to blacken a surface or as a solid lubricant.[10] Even when molybdena was distinguishable from graphite, it was still confused with the common lead ore PbS (now called galena); the name comes from Ancient Greek Μόλυβδος molybdos, meaning lead.[11] (The Greek word itself has been proposed as a loanword from Anatolian Luvian and Lydian languages).[12]

Although (reportedly) molybdenum was deliberately alloyed with steel in one 14th-century Japanese sword (mfd. ح. 1330), that art was never employed widely and was later lost.[13][14] In the West in 1754, Bengt Andersson Qvist examined a sample of molybdenite and determined that it did not contain lead and thus was not galena.[15]

By 1778 Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele stated firmly that molybdena was (indeed) neither galena nor graphite.[16][17] Instead, Scheele correctly proposed that molybdena was an ore of a distinct new element, named molybdenum for the mineral in which it resided, and from which it might be isolated. Peter Jacob Hjelm successfully isolated molybdenum using carbon and linseed oil in 1781.[11][18]

For the next century, molybdenum had no industrial use. It was relatively scarce, the pure metal was difficult to extract, and the necessary techniques of metallurgy were immature.[19][20][21] Early molybdenum steel alloys showed great promise of increased hardness, but efforts to manufacture the alloys on a large scale were hampered with inconsistent results, a tendency toward brittleness, and recrystallization. In 1906, William D. Coolidge filed a patent for rendering molybdenum ductile, leading to applications as a heating element for high-temperature furnaces and as a support for tungsten-filament light bulbs; oxide formation and degradation require that molybdenum be physically sealed or held in an inert gas.[22] In 1913, Frank E. Elmore developed a froth flotation process to recover molybdenite from ores; flotation remains the primary isolation process.[23]

During World War I, demand for molybdenum spiked; it was used both in armor plating and as a substitute for tungsten in high-speed steels. Some British tanks were protected by 75 mm (3 in) manganese steel plating, but this proved to be ineffective. The manganese steel plates were replaced with much lighter 25 mm (1.0 in) molybdenum steel plates allowing for higher speed, greater maneuverability, and better protection.[11] The Germans also used molybdenum-doped steel for heavy artillery, like in the super-heavy howitzer Big Bertha,[24] because traditional steel melts at the temperatures produced by the propellant of the one ton shell.[25] After the war, demand plummeted until metallurgical advances allowed extensive development of peacetime applications. In World War II, molybdenum again saw strategic importance as a substitute for tungsten in steel alloys.[26]

التواجد والانتاج

يشغل المولبدن 10-3% وزناً من القشرة الأرضية. وهو يوجد على شكل مولبدنيت؛ وهو كبر يتيد المولبدن MoS2، ويتطلب تحضيره استحصال الأكاسيد من خاماتها، ويتم ذلك بصهر الخامات مع كربونات الصوديوم وبإمرار تيار من الأكسجين:

ثم يعالج الملح Na2MoO4 بحمض HCl، فينتج الحمض H2MoO4. يعزل الحمض الحاصل من المحلول ثم يحوّل إلى أكسيد المولبدن VI بالتسخين. يُرجَع الأكسيد بالهدروجين (أو الكربون) عند درجة عالية من الحرارة، فينتج Mo.

يستعمل المولبدن في صنع عدة سبائك خاصة؛ منها الفولاذ؛ وفي عدة مجالات صناعية. فهو يدخل في صنع فولاذ من نوع خاص يستعمل في صناعة الطائرات والسيارات والأسلحة ولصنع الأفران شديدة السخونة. ويستعمل ثنائي كبريتيد المولبدن في التشحيم.

المولبدن ذو قساوة متوسطة، ويمكن صقله ولحمه عند درجات عالية من الحرارة، كما أنه ناقل جيد للكهرباء (30% من ناقلية الفضة). وهو قابل للسحب والطرق على نحو جيّد عندما يكون نقياً، ويصبح هشاً قابلاً للكسر إذا دخلته كمية ضئيلة من الشوائب. وهو لين نسبياً. يستعمل في التعدين إذ يدخل في كثير من السبائك؛ فيكسبها قساوة ومقاومة للتآكل بالمؤثرات الخارجية.

التعدين

The Knaben mine in southern Norway, opened in 1885, was the first dedicated molybdenum mine. Closed in 1973 but reopened in 2007,[27] it now produces 100،000 كيلوغرام (98 long ton; 110 short ton) of molybdenum disulfide per year. Large mines in Colorado (such as the Henderson mine and the Climax mine)[28] and in British Columbia yield molybdenite as their primary product, while many porphyry copper deposits such as the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah and the Chuquicamata mine in northern Chile produce molybdenum as a byproduct of copper-mining.

التطبيقات

السبائك

About 86% of molybdenum produced is used in metallurgy, with the rest used in chemical applications. The estimated global use is structural steel 35%, stainless steel 25%, chemicals 14%, tool & high-speed steels 9%, cast iron 6%, molybdenum elemental metal 6%, and superalloys 5%.[29]

Molybdenum can withstand extreme temperatures without significantly expanding or softening, making it useful in environments of intense heat, including military armor, aircraft parts, electrical contacts, industrial motors, and supports for filaments in light bulbs.[11][30]

Most high-strength steel alloys (for example, 41xx steels) contain 0.25% to 8% molybdenum.[31] Even in these small portions, more than 43,000 tonnes of molybdenum are used each year in stainless steels, tool steels, cast irons, and high-temperature superalloys.[32]

Molybdenum is also used in steel alloys for its high corrosion resistance and weldability.[32][33] Molybdenum contributes corrosion resistance to type-300 stainless steels (specifically type-316) and especially so in the so-called superaustenitic stainless steels (such as alloy AL-6XN, 254SMO and 1925hMo). Molybdenum increases lattice strain, thus increasing the energy required to dissolve iron atoms from the surface.[contradictory] Molybdenum is also used to enhance the corrosion resistance of ferritic (for example grade 444)[34] and martensitic (for example 1.4122 and 1.4418) stainless steels.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Because of its lower density and more stable price, molybdenum is sometimes used in place of tungsten.[32] An example is the 'M' series of high-speed steels such as M2, M4 and M42 as substitution for the 'T' steel series, which contain tungsten. Molybdenum can also be used as a flame-resistant coating for other metals. Although its melting point is 2،623 °C (4،753 °F), molybdenum rapidly oxidizes at temperatures above 760 °C (1،400 °F) making it better-suited for use in vacuum environments.[30]

TZM (Mo (~99%), Ti (~0.5%), Zr (~0.08%) and some C) is a corrosion-resisting molybdenum superalloy that resists molten fluoride salts at temperatures above 1،300 °C (2،370 °F). It has about twice the strength of pure Mo, and is more ductile and more weldable, yet in tests it resisted corrosion of a standard eutectic salt (FLiBe) and salt vapors used in molten salt reactors for 1100 hours with so little corrosion that it was difficult to measure.[35][36] Due to its excellent mechanical properties under high temperature and high pressure, TZM alloys are extensively applied in the military industry.[37] It is used as the valve body of torpedo engines, rocket nozzles and gas pipelines, where it can withstand extreme thermal and mechanical stresses.[38][39] It is also used as radiation shields in nuclear applications.[40]

Other molybdenum-based alloys that do not contain iron have only limited applications. For example, because of its resistance to molten zinc, both pure molybdenum and molybdenum-tungsten alloys (70%/30%) are used for piping, stirrers and pump impellers that come into contact with molten zinc.[41]

استخدامات العنصر النقي

- Molybdenum powder is used as a fertilizer for some plants, such as cauliflower.[32]

- Elemental molybdenum is used in NO, NO2, NOx analyzers in power plants for pollution controls. At 350 °C (662 °F), the element acts as a catalyst for NO2/NOx to form NO molecules for detection by infrared light.[42]

- Molybdenum anodes replace tungsten in certain low voltage X-ray sources for specialized uses such as mammography.[43]

- The radioactive isotope molybdenum-99 is used to generate technetium-99m, used for medical imaging[44] The isotope is handled and stored as the molybdate.[45]

تطبيقات المركبات

- Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is used as a solid lubricant and a high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) anti-wear agent. It forms strong films on metallic surfaces and is a common additive to HPHT greases — in the event of a catastrophic grease failure, a thin layer of molybdenum prevents contact of the lubricated parts.[46]

- When combined with small amounts of cobalt, MoS2 is also used as a catalyst in the hydrodesulfurization (HDS) of petroleum. In the presence of hydrogen, this catalyst facilitates the removal of nitrogen and especially sulfur from the feedstock, which otherwise would poison downstream catalysts. HDS is one of the largest scale applications of catalysis in industry.[47]

- Molybdenum oxides are important catalysts for selective oxidation of organic compounds. The production of the commodity chemicals acrylonitrile and formaldehyde relies on MoOx-based catalysts.[48]

- Molybdenum disilicide (MoSi2) is an electrically conducting ceramic with primary use in heating elements operating at temperatures above 1500 °C in air.[49]

- Molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) is used as an adhesive between enamels and metals.[16]

- Lead molybdate (wulfenite) co-precipitated with lead chromate and lead sulfate is a bright-orange pigment used with ceramics and plastics.[50]

- The molybdenum-based mixed oxides are versatile catalysts in the chemical industry. Some examples are the catalysts for the oxidation of carbon monoxide, propylene to acrolein and acrylic acid, the ammoxidation of propylene to acrylonitrile.[51][52]

- Molybdenum carbides, nitride and phosphides can be used for hydrotreatment of rapeseed oil.[53]

- Ammonium heptamolybdate is used in biological staining.[54]

- Molybdenum coated soda lime glass is used in CIGS (copper indium gallium selenide) solar cells, called CIGS solar cells.

- Phosphomolybdic acid is a stain used in thin-layer chromatography[55] and trichrome staining in histochemistry.[56]

الدور الحيوي

Molybdenum, despite its low concentration in the environment, is a critically important element for Earth's biosphere due to its presence in the most common nitrogenases. Without molybdenum, nitrogen fixation would be greatly reduced, and a large part of biosynthesis as we know it would not occur. Molybdenum is also essential to many individual organisms as a component of enzymes, particularly as part of the molybdopterin class of cofactors.

Mo-containing enzymes

Molybdenum is an essential element in most organisms; a 2008 research paper speculated that a scarcity of molybdenum in the Earth's early oceans may have strongly influenced the evolution of eukaryotic life (which includes all plants and animals).[57]

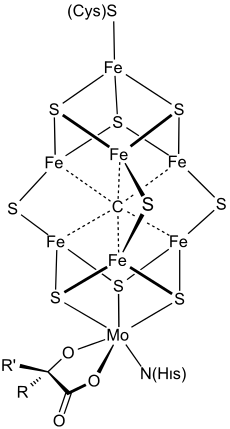

At least 50 molybdenum-containing enzymes have been identified, mostly in bacteria.[58][59] Those enzymes include aldehyde oxidase, sulfite oxidase and xanthine oxidase.[11] With one exception, Mo in proteins is bound by molybdopterin to give the molybdenum cofactor. The only known exception is nitrogenase, which uses the FeMoco cofactor, which has the formula Fe7MoS9C.[60]

In terms of function, molybdoenzymes catalyze the oxidation and sometimes reduction of certain small molecules in the process of regulating nitrogen, sulfur, and carbon.[61] In some animals, and in humans, the oxidation of xanthine to uric acid, a process of purine catabolism, is catalyzed by xanthine oxidase, a molybdenum-containing enzyme. The activity of xanthine oxidase is directly proportional to the amount of molybdenum in the body. An extremely high concentration of molybdenum reverses the trend and can inhibit purine catabolism and other processes. Molybdenum concentration also affects protein synthesis, metabolism, and growth.[62]

Mo is a component in most nitrogenases. Among molybdoenzymes, nitrogenases are unique in lacking the molybdopterin.[63][64] Nitrogenases catalyze the production of ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen:

The biosynthesis of the FeMoco active site is highly complex.[65]

Molybdate is transported in the body as MoO42−.[62]

Human metabolism and deficiency

Molybdenum is an essential trace dietary element.[66] Four mammalian Mo-dependent enzymes are known, all of them harboring a pterin-based molybdenum cofactor (Moco) in their active site: sulfite oxidase, xanthine oxidoreductase, aldehyde oxidase, and mitochondrial amidoxime reductase.[67] People severely deficient in molybdenum have poorly functioning sulfite oxidase and are prone to toxic reactions to sulfites in foods.[68][69] The human body contains about 0.07 mg of molybdenum per kilogram of body weight,[70] with higher concentrations in the liver and kidneys and lower in the vertebrae.[32] Molybdenum is also present within human tooth enamel and may help prevent its decay.[71]

Acute toxicity has not been seen in humans, and the toxicity depends strongly on the chemical state. Studies on rats show a median lethal dose (LD50) as low as 180 mg/kg for some Mo compounds.[72] Although human toxicity data is unavailable, animal studies have shown that chronic ingestion of more than 10 mg/day of molybdenum can cause diarrhea, growth retardation, infertility, low birth weight, and gout; it can also affect the lungs, kidneys, and liver.[73][74] Sodium tungstate is a competitive inhibitor of molybdenum. Dietary tungsten reduces the concentration of molybdenum in tissues.[32]

Low soil concentration of molybdenum in a geographical band from northern China to Iran results in a general dietary molybdenum deficiency and is associated with increased rates of esophageal cancer.[75][76][77] Compared to the United States, which has a greater supply of molybdenum in the soil, people living in those areas have about 16 times greater risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.[78]

Molybdenum deficiency has also been reported as a consequence of non-molybdenum supplemented total parenteral nutrition (complete intravenous feeding) for long periods of time. It results in high blood levels of sulfite and urate, in much the same way as molybdenum cofactor deficiency. Since pure molybdenum deficiency from this cause occurs primarily in adults, the neurological consequences are not as marked as in cases of congenital cofactor deficiency.[79]

A congenital molybdenum cofactor deficiency disease, seen in infants, is an inability to synthesize molybdenum cofactor, the heterocyclic molecule discussed above that binds molybdenum at the active site in all known human enzymes that use molybdenum. The resulting deficiency results in high levels of sulfite and urate, and neurological damage.[80][81]

Excretion

Most molybdenum is excreted from the human body as molybdate in the urine. Furthermore, urinary excretion of molybdenum increases as dietary molybdenum intake increases. Small amounts of molybdenum are excreted from the body in the feces by way of the bile; small amounts also can be lost in sweat and in hair.[82][83]

Excess and copper antagonism

High levels of molybdenum can interfere with the body's uptake of copper, producing copper deficiency. Molybdenum prevents plasma proteins from binding to copper, and it also increases the amount of copper that is excreted in urine. Ruminants that consume high levels of molybdenum suffer from diarrhea, stunted growth, anemia, and achromotrichia (loss of fur pigment). These symptoms can be alleviated by copper supplements, either dietary and injection.[84] The effective copper deficiency can be aggravated by excess sulfur.[32][85]

Copper reduction or deficiency can also be deliberately induced for therapeutic purposes by the compound ammonium tetrathiomolybdate, in which the bright red anion tetrathiomolybdate is the copper-chelating agent. Tetrathiomolybdate was first used therapeutically in the treatment of copper toxicosis in animals. It was then introduced as a treatment in Wilson's disease, a hereditary copper metabolism disorder in humans; it acts both by competing with copper absorption in the bowel and by increasing excretion. It has also been found to have an inhibitory effect on angiogenesis, potentially by inhibiting the membrane translocation process that is dependent on copper ions.[86] This is a promising avenue for investigation of treatments for cancer, age-related macular degeneration, and other diseases that involve a pathologic proliferation of blood vessels.[87][88]

In some grazing livestock, most strongly in cattle, molybdenum excess in the soil of pasturage can produce scours (diarrhea) if the pH of the soil is neutral to alkaline; see teartness.

Mammography

Molybdenum targets are used in mammography because they produce X-rays in the energy range of 17-20 keV, which is optimal for imaging soft tissues like the breast.[89][90] The characteristic X-rays emitted from molybdenum provide high contrast between different types of tissues, allowing for the effective visualization of microcalcifications and other subtle abnormalities in breast tissue.[91] This energy range also minimizes radiation dose while maximizing image quality, making molybdenum targets particularly suitable for breast cancer screening.[92]

الإنزيمات التي تحتوي موليبدنم كتميم:

Dietary recommendations

In 2000, the then U.S. Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine, NAM) updated its Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for molybdenum. If there is not sufficient information to establish EARs and RDAs, an estimate designated Adequate Intake (AI) is used instead.

An AI of 2 micrograms (μg) of molybdenum per day was established for infants up to 6 months of age, and 3 μg/day from 7 to 12 months of age, both for males and females. For older children and adults, the following daily RDAs have been established for molybdenum: 17 μg from 1 to 3 years of age, 22 μg from 4 to 8 years, 34 μg from 9 to 13 years, 43 μg from 14 to 18 years, and 45 μg for persons 19 years old and older. All these RDAs are valid for both sexes. Pregnant or lactating females from 14 to 50 years of age have a higher daily RDA of 50 μg of molybdenum.

As for safety, the NAM sets tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of molybdenum, the UL is 2000 μg/day. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).[93]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL are defined the same as in the United States. For women and men ages 15 and older, the AI is set at 65 μg/day. Pregnant and lactating women have the same AI. For children aged 1–14 years, the AIs increase with age from 15 to 45 μg/day. The adult AIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs,[94] but on the other hand, the European Food Safety Authority reviewed the same safety question and set its UL at 600 μg/day, which is much lower than the U.S. value.[95]

Labeling

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes, the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For molybdenum labeling purposes, 100% of the Daily Value was 75 μg, but as of May 27, 2016 it was revised to 45 μg.[96][97] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

المصادر الغذائية

Average daily intake varies between 120 and 240 μg/day, which is higher than dietary recommendations.[73] Pork, lamb, and beef liver each have approximately 1.5 parts per million of molybdenum. Other significant dietary sources include green beans, eggs, sunflower seeds, wheat flour, lentils, cucumbers, and cereal grain.[11]

احتياطات

Molybdenum dusts and fumes, generated by mining or metalworking, can be toxic, especially if ingested (including dust trapped in the sinuses and later swallowed).[72] Low levels of prolonged exposure can cause irritation to the eyes and skin. Direct inhalation or ingestion of molybdenum and its oxides should be avoided.[98][99] OSHA regulations specify the maximum permissible molybdenum exposure in an 8-hour day as 5 mg/m3. Chronic exposure to 60 to 600 mg/m3 can cause symptoms including fatigue, headaches and joint pains.[100] At levels of 5000 mg/m3, molybdenum is immediately dangerous to life and health.[101]

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHoll - ^ Schmidt, Max (1968). "VI. Nebengruppe". Anorganische Chemie II (in German). Wissenschaftsverlag. pp. 119–127.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Pope, Michael T.; Müller, Achim (1997). "Polyoxometalate Chemistry: An Old Field with New Dimensions in Several Disciplines". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 30: 34–48. doi:10.1002/anie.199100341.

- ^ Nollet, Leo M. L., ed. (2000). Handbook of water analysis. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. pp. 280–288. ISBN 978-0-8247-8433-1.

- ^ Tamadon, Farhad; Seppelt, Konrad (2013-01-07). "The Elusive Halides VCl 5, MoCl 6, and ReCl 6". Angewandte Chemie International Edition (in الإنجليزية). 52 (2): 767–769. doi:10.1002/anie.201207552. PMID 23172658.

- ^ قالب:Kirk-Othmer

- ^ Walton, Richard A.; Fanwick, Phillip E.; Girolami, Gregory S.; Murillo, Carlos A.; Johnstone, Erik V. (2014). Girolami, Gregory S.; Sattelberger, Alfred P. (eds.). Inorganic Syntheses: Volume 36 (in الإنجليزية). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 78–81. doi:10.1002/9781118744994.ch16. ISBN 978-1118744994.

- ^ Drago, Russell S.; Long, John R.; Cosmano, Richard (1982-06-01). "Comparison of the coordination chemistry and inductive transfer through the metal-metal bond in adducts of dirhodium and dimolybdenum carboxylates". Inorganic Chemistry (in الإنجليزية). 21 (6): 2196–2202. doi:10.1021/ic00136a013. ISSN 0020-1669.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةauto - ^ Lansdown, A. R. (1999). Molybdenum disulphide lubrication. Tribology and Interface Engineering. Vol. 35. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-50032-8.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnbb - ^ Melchert, Craig. "Greek mólybdos as a Loanword from Lydian" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Molybdenum History". International Molybdenum Association. Archived from the original on 2013-07-22.

- ^ Accidental use of molybdenum in old sword led to new alloy. American Iron and Steel Institute. 1948.

- ^ Van der Krogt, Peter (2006-01-10). "Molybdenum". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Archived from the original on 2010-01-23. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ أ ب Gagnon, Steve. "Molybdenum". Jefferson Science Associates, LLC. Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ Scheele, C. W. K. (1779). "Versuche mit Wasserbley; Molybdaena". Svenska Vetensk. Academ. Handlingar. 40: 238.

- ^ Hjelm, P. J. (1788). "Versuche mit Molybdäna, und Reduction der selben Erde". Svenska Vetensk. Academ. Handlingar. 49: 268.

- ^ Hoyt, Samuel Leslie (1921). Metallography. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Krupp, Alfred; Wildberger, Andreas (1888). The metallic alloys: A practical guide for the manufacture of all kinds of alloys, amalgams, and solders, used by metal-workers ... with an appendix on the coloring of alloys. H.C. Baird & Co. p. 60.

- ^ Gupta, C. K. (1992). Extractive Metallurgy of Molybdenum. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4758-0.

- ^ Reich, Leonard S. (2002-08-22). The Making of American Industrial Research: Science and Business at Ge and Bell, 1876–1926. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0521522373. Archived from the original on 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- ^ Vokes, Frank Marcus (1963). Molybdenum deposits of Canada. p. 3.

- ^ Chemical properties of molibdenum – Health effects of molybdenum – Environmental effects of molybdenum Archived 2016-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. lenntech.com

- ^ Kean, Sam (2011-06-06). The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements (in English) (Illustrated ed.). Back Bay Books. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-316-05163-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Millholland, Ray (August 1941). "Battle of the Billions: American industry mobilizes machines, materials, and men for a job as big as digging 40 Panama Canals in one year". Popular Science: 61. Archived from the original on 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- ^ Langedal, M. (1997). "Dispersion of tailings in the Knabena—Kvina drainage basin, Norway, 1: Evaluation of overbank sediments as sampling medium for regional geochemical mapping". Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 58 (2–3): 157–172. Bibcode:1997JCExp..58..157L. doi:10.1016/S0375-6742(96)00069-6.

- ^ Coffman, Paul B. (1937). "The Rise of a New Metal: The Growth and Success of the Climax Molybdenum Company". The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago. 10: 30. doi:10.1086/232443.

- ^ "Molybdenum". Industry usage. London Metal Exchange. Archived from the original on 2012-03-10.

- ^ أ ب "Molybdenum". AZoM.com Pty. Limited. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCRCdescription2 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNostrand - ^ "Molybdenum Statistics and Information". U.S. Geological Survey. 2007-05-10. Archived from the original on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ (2023) Stainless Steel Grades and Properties. International Molybdenum Association. https://www.imoa.info/molybdenum-uses/molybdenum-grade-stainless-steels/steel-grades.php?m=1683978651&

- ^ Smallwood, Robert E. (1984). "TZM Moly Alloy". ASTM special technical publication 849: Refractory metals and their industrial applications: a symposium. ASTM International. p. 9. ISBN 978-0803102033.

- ^ "Compatibility of Molybdenum-Base Alloy TZM, with LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4". Oak Ridge National Laboratory Report. December 1969. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ Levy, M. (1965). "A protective coating system for a TZM alloy re-entry vehicle" (PDF). US Army. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Yang, Zhi; Hu, Ke (2018). "Diffusion bonding between TZM alloy and WRe alloy by spark plasma sintering". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 764: 582–590. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.06.111.

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ Trento, Chin (Dec 27, 2023). "Preparation & Application of TZM Alloy". Stanford Advanced Materials. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Cubberly, W. H.; Bakerjian, Ramon (1989). Tool and manufacturing engineers handbook. Society of Manufacturing Engineers. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-87263-351-3.

- ^ Lal, S.; Patil, R. S. (2001). "Monitoring of atmospheric behaviour of NOx from vehicular traffic". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 68 (1): 37–50. Bibcode:2001EMnAs..68...37L. doi:10.1023/A:1010730821844. PMID 11336410. S2CID 20441999.

- ^ Lancaster, Jack L. "Ch. 4: Physical determinants of contrast" (PDF). Physics of Medical X-Ray Imaging. University of Texas Health Science Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-10.

- ^ Gray, Theodore (2009). The Elements. Black Dog & Leventhal. pp. 105–107. ISBN 1-57912-814-9.

- ^ Gottschalk, A. (1969). "Technetium-99m in clinical nuclear medicine". Annual Review of Medicine. 20 (1): 131–40. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.20.020169.001023. PMID 4894500.

- ^ Winer, W. (1967). "Molybdenum disulfide as a lubricant: A review of the fundamental knowledge" (PDF). Wear. 10 (6): 422–452. doi:10.1016/0043-1648(67)90187-1. hdl:2027.42/33266.

- ^ Topsøe, H.; Clausen, B. S.; Massoth, F. E. (1996). Hydrotreating Catalysis, Science and Technology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةullmann - ^ Moulson, A. J.; Herbert, J. M. (2003). Electroceramics: materials, properties, applications. John Wiley and Sons. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-471-49748-6.

- ^ International Molybdenum Association Archived 2008-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. imoa.info.

- ^ Fierro, J. G. L., ed. (2006). Metal Oxides, Chemistry and Applications. CRC Press. pp. 414–455.

- ^ Centi, G.; Cavani, F.; Trifiro, F. (2001). Selective Oxidation by Heterogeneous Catalysis. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 363–384.

- ^ Horáček, Jan; Akhmetzyanova, Uliana; Skuhrovcová, Lenka; Tišler, Zdeněk; de Paz Carmona, Héctor (1 April 2020). "Alumina-supported MoNx, MoCx and MoPx catalysts for the hydrotreatment of rapeseed oil". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental (in الإنجليزية). 263: 118328. Bibcode:2020AppCB.26318328H. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118328. ISSN 0926-3373. S2CID 208758175.

- ^ De Carlo, Sacha; Harris, J. Robin (2011). "Negative staining and cryo-negative staining of macromolecules and viruses for TEM". Micron. 42 (2): 117–131. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2010.06.003. PMC 2978762. PMID 20634082.

- ^ "Stains for Developing TLC Plates" (PDF). McMaster University.

- ^ Everett, M.M.; Miller, W.A. (1974). "The role of phosphotungstic and phosphomolybdic acids in connective tissue staining I. Histochemical studies". The Histochemical Journal. 6 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1007/BF01011535. PMID 4130630.

- ^ Scott, C.; Lyons, T. W.; Bekker, A.; Shen, Y.; Poulton, S. W.; Chu, X.; Anbar, A. D. (2008). "Tracing the stepwise oxygenation of the Proterozoic ocean". Nature. 452 (7186): 456–460. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..456S. doi:10.1038/nature06811. PMID 18368114. S2CID 205212619.

- ^ Enemark, John H.; Cooney, J. Jon A.; Wang, Jun-Jieh; Holm, R. H. (2004). "Synthetic Analogues and Reaction Systems Relevant to the Molybdenum and Tungsten Oxotransferases". Chem. Rev. 104 (2): 1175–1200. doi:10.1021/cr020609d. PMID 14871153.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R.; Bittner, Florian (2006). "Cell biology of molybdenum". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1763 (7): 621–635. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.013. PMID 16784786.

- ^ Russ Hille; James Hall; Partha Basu (2014). "The Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzymes". Chem. Rev. 114 (7): 3963–4038. doi:10.1021/cr400443z. PMC 4080432. PMID 24467397.

- ^ Kisker, C.; Schindelin, H.; Baas, D.; Rétey, J.; Meckenstock, R. U.; Kroneck, P. M. H. (1999). "A structural comparison of molybdenum cofactor-containing enzymes" (PDF). FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22 (5): 503–521. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00384.x. PMID 9990727. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ أ ب Mitchell, Phillip C. H. (2003). "Overview of Environment Database". International Molybdenum Association. Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R. (2013). "Chapter 15 Metabolism of Molybdenum". In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_15 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of نوفمبر 2024 (link) electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 قالب:Issn electronic-قالب:Issn - ^ Chi Chung, Lee; Markus W., Ribbe; Yilin, Hu (2014). "Biochemistry of Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase: The Nickel Metalloenzyme that Catalyzes the Final Step in Synthesis and the First Step in Anaerobic Oxidation of the Greenhouse Gas Methane". In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 147–174. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_6. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416393.

- ^ Dos Santos, Patricia C.; Dean, Dennis R. (2008). "A newly discovered role for iron-sulfur clusters". PNAS. 105 (33): 11589–11590. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511589D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805713105. PMC 2575256. PMID 18697949.

- ^ Schwarz, Guenter; Belaidi, Abdel A. (2013). "Molybdenum in Human Health and Disease". In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 415–450. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_13. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470099.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R. (2009). "Cell biology of molybdenum". BioFactors. 35 (5): 429–34. doi:10.1002/biof.55. PMID 19623604. S2CID 205487570.

- ^ Blaylock Wellness Report, February 2010, page 3.

- ^ Cohen, H. J.; Drew, R. T.; Johnson, J. L.; Rajagopalan, K. V. (1973). "Molecular Basis of the Biological Function of Molybdenum. The Relationship between Sulfite Oxidase and the Acute Toxicity of Bisulfite and SO2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 70 (12 Pt 1–2): 3655–3659. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.3655C. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.12.3655. PMC 427300. PMID 4519654.

- ^ Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. p. 1384. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Curzon, M. E. J.; Kubota, J.; Bibby, B. G. (1971). "Environmental Effects of Molybdenum on Caries". Journal of Dental Research. 50 (1): 74–77. doi:10.1177/00220345710500013401. S2CID 72386871.

- ^ أ ب "Risk Assessment Information System: Toxicity Summary for Molybdenum". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ أ ب Coughlan, M. P. (1983). "The role of molybdenum in human biology". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 6 (S1): 70–77. doi:10.1007/BF01811327. PMID 6312191. S2CID 10114173.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G.; Barceloux, Donald (1999). "Molybdenum". Clinical Toxicology. 37 (2): 231–237. doi:10.1081/CLT-100102422. PMID 10382558.

- ^ Yang, Chung S. (1980). "Research on Esophageal Cancer in China: a Review" (PDF). Cancer Research. 40 (8 Pt 1): 2633–44. PMID 6992989. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ Nouri, Mohsen; Chalian, Hamid; Bahman, Atiyeh; Mollahajian, Hamid; et al. (2008). "Nail Molybdenum and Zinc Contents in Populations with Low and Moderate Incidence of Esophageal Cancer" (PDF). Archives of Iranian Medicine. 11 (4): 392–6. PMID 18588371. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ Zheng, Liu; et al. (1982). "Geographical distribution of trace elements-deficient soils in China". Acta Ped. Sin. 19: 209–223. Archived from the original on 2021-02-05. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- ^ Taylor, Philip R.; Li, Bing; Dawsey, Sanford M.; Li, Jun-Yao; Yang, Chung S.; Guo, Wande; Blot, William J. (1994). "Prevention of Esophageal Cancer: The Nutrition Intervention Trials in Linxian, China" (PDF). Cancer Research. 54 (7 Suppl): 2029s–2031s. PMID 8137333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- ^ Abumrad, N. N. (1984). "Molybdenum—is it an essential trace metal?". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 60 (2): 163–71. PMC 1911702. PMID 6426561.

- ^ Smolinsky, B; Eichler, S. A.; Buchmeier, S.; Meier, J. C.; Schwarz, G. (2008). "Splice-specific Functions of Gephyrin in Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (25): 17370–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800985200. PMID 18411266.

- ^ Reiss, J. (2000). "Genetics of molybdenum cofactor deficiency". Human Genetics. 106 (2): 157–63. doi:10.1007/s004390051023 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 10746556.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of نوفمبر 2024 (link) - ^ Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.; Carr, Timothy P. (2016-10-05). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (in الإنجليزية). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-337-51421-7.

- ^ Turnlund, J. R.; Keyes, W. R.; Peiffer, G. L. (October 1995). "Molybdenum absorption, excretion, and retention studied with stable isotopes in young men at five intakes of dietary molybdenum". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 62 (4): 790–796. doi:10.1093/ajcn/62.4.790. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 7572711.

- ^ Suttle, N. F. (1974). "Recent studies of the copper-molybdenum antagonism". Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 33 (3): 299–305. doi:10.1079/PNS19740053. PMID 4617883.

- ^ Hauer, Gerald Copper deficiency in cattle Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. Bison Producers of Alberta. Accessed Dec. 16, 2010.

- ^ Nickel, W (2003). "The Mystery of nonclassical protein secretion, a current view on cargo proteins and potential export routes". Eur. J. Biochem. 270 (10): 2109–2119. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03577.x. PMID 12752430.

- ^ Brewer GJ; Hedera, P.; Kluin, K. J.; Carlson, M.; Askari, F.; Dick, R. B.; Sitterly, J.; Fink, J. K. (2003). "Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate: III. Initial therapy in a total of 55 neurologically affected patients and follow-up with zinc therapy". Arch Neurol. 60 (3): 379–85. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.3.379. PMID 12633149.

- ^ Brewer, G. J.; Dick, R. D.; Grover, D. K.; Leclaire, V.; Tseng, M.; Wicha, M.; Pienta, K.; Redman, B. G.; Jahan, T.; Sondak, V. K.; Strawderman, M.; LeCarpentier, G.; Merajver, S. D. (2000). "Treatment of metastatic cancer with tetrathiomolybdate, an anticopper, antiangiogenic agent: Phase I study". Clinical Cancer Research. 6 (1): 1–10. PMID 10656425.

- ^ Green, Julissa. "Why is Molybdenum Target Used in Mammography for Breast Cancer?". Sputter Targets. Retrieved Aug 2, 2024.

- ^ "2. Screening Techniques". IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Interventions: Breast cancer screening. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2016. Retrieved Sep 2, 2024.

- ^ Su, Qi-Hang; Zhang, Yan (2020). "Application of molybdenum target X-ray photography in imaging analysis of caudal intervertebral disc degeneration in rats". World J Clin Cases. 8 (6): 3431–3439. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3431. PMC 7457105. PMID 32913849.

- ^ Alkhalifah, Khaled; Asbeutah, Akram (2020). "Image Quality and Radiation Dose for Fibrofatty Breast using Target/filter Combinations in Two Digital Mammography Systems". J Clin Imaging Sci. 10 (56): 56. doi:10.25259/JCIS_30_2020. PMC 7533093. PMID 33024611.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2000). "Molybdenum". Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 420–441. doi:10.17226/10026. ISBN 978-0-309-07279-3. PMID 25057538. S2CID 44243659.

- ^ "Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies" (PDF). 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals, European Food Safety Authority, 2006, http://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/efsa_rep/blobserver_assets/ndatolerableuil.pdf, retrieved on 2017-09-10

- ^ "Federal Register May 27, 2016 Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FR page 33982" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)". Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet – Molybdenum". The REMBAR Company, Inc. 2000-09-19. Archived from the original on March 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet – Molybdenum Powder". CERAC, Inc. 1994-02-23. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ "NIOSH Documentation for IDLHs Molybdenum". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 1996-08-16. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Molybdenum". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

وصلات خارجية

- WebElements.com — Molybdenum

- International Molybdenum Association — Main page

| الجدول الدوري | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Uub | Uut | Uuq | Uup | Uuh | Uus | Uuo | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of نوفمبر 2024

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- All self-contradictory articles

- Self-contradictory articles from September 2018

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2014

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- معادن غذائية

- مولبدنم

- فلزات انتقالية

- مواد حرارية

- علما الأحياء والأدوية للعناصر الكيميائية

- عناصر كيميائية