دونمه

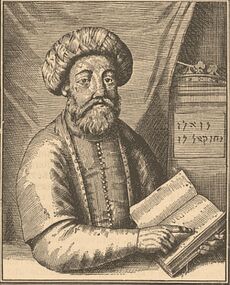

الدونمه (بالعبرية: דוֹנְמֶה، تركية عثمانية: دونمه، تركية: Dönme، إنگليزية: Dönmeh)، هم مجموعة من اليهود المتخفيين الشبطائيين في الدولة العثمانية الذين أُجبروا على اعتناق الإسلام، لكنهم احتفظوا بإيمانهم اليهودي واعتقاداتهم القبالية سراً.[1][2][3][4] كانت الحركة تتركز بشكل أساسي في سالونيك.[1][4][5] ونشأت خلال فترة قصيرة بعد عصر شبطاي تسڤي، وهو حاخام يهودي سفرديم قبالي من القرن السابع عشر ادعى أنه المسيح اليهودي المنتظر وفي النهاية اعتنق الإسلام قسراً في عهد السلطان محمد الرابع.[3][6] بعدما أُجبر تسڤي على اعتناق الإسلام،[1][3][4][6] ادعى عدد من الشبطائيين اعتناقهم الإسلام وأصبحوا الدونمه.[1][3][4][7] حتى القرن 21 كان هناك بعض الشبطائيين يعيشون في تركيا كأحفاد للدونمه.[1]

اليوم لا يُعرف على وجه الدقة أعداد الأشخاص الذين ما زالوا يطلقون على أنفسهم اسم دونمه، على الرغم من أن بعضهم ما زالوا يعيشون في تشويقيه في إسطنبول]. دُفن معظمهم في مقبرة بولبولدر في أسكدار حيث تتميز شواهد قبورهم، على نحو غير معتاد، بصور المتوفى.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التسمية

كلمة دونمه التركية dönme (المرتد)[1][4] مشتقة من دون- dön- وتعني "يتحول". وقد عرّف الباحث التركي المستقل رفعت بالي مصطلح الدونمة على النحو التالي:

إن مصطلح "دونمه" هو اسم مصدر تركي يعني "التحول أو الدوران أو العودة"، وبالتالي "الخيانة" (أي "العودة") و"التحول" إلى دين آخر. وقد أصبح المصطلح يستخدم في اللغة الشعبية للإشارة إلى المتحولين دينياً بشكل عام، وبشكل أكثر تحديداً إلى أتباع المسيح اليهودي الكاذب شبطاي تسڤي في القرن السابع عشر وذريتهم، الذين تحولوا ظاهرياً إلى الإسلام ولكنهم احتفظوا بممارساتهم الدينية السرية على مدى القرون العديدة التالية، وحافظوا على روابط طائفية وثيقة وممارسة صارمة لزواج الأقارب. وفي حين تخلت الغالبية العظمى من أعضاء الجالية عن ممارساتهم خلال الربع الأول من القرن، فإن هويتهم الماضية استمرت في مطاردتهم داخل المجتمع التركي، وظل مصطلح "دونمه" نفسه مصطلحاً مذموماً.[8]

التاريخ

على الرغم من اعتناقهم المزعوم للإسلام، ظل الشبطائيون محتفظين بيهوديتهم واستمروا في ممارسة الطقوس اليهودية سراً.[1][2] لقد اعترفوا بشبطاي تسڤي (1626-1676) باعتباره المسيح اليهودي، وطبقوا بعض الوصايا اليهودية التي تشبه تلك الموجودة في اليهودية الحاخامية،[1][2] وكانوا يصلون بالعبرية واليهودية الإسپانية. كما مارسوا طقوسًا للاحتفال بالأحداث الهامة في حياة تسڤي وفسروا اعتناق تسڤي للإسلام بالطريقة القباليه.[1][2]

انقسمت الدونمة إلى عدة فروع. الأول، الدونمه إزميرلي، تشكل في إزمير (سميرنا) وكان الطائفة الأصلية، والتي انفصلت عنها في النهاية طائفتان أخريان. أدى الانشقاق الأول إلى تشكلت طائفة اليعقوبيين، التي أسسها يعقوب كويريدو (ح. 1650-1690)، شقيق زوجة تسڤي الأخيرة. ادعى كويريدو أنه تجسيد لتسڤي والمسيح في حد ذاته. كان الانقسام الثاني عن إزميرلي نتيجة لادعاءات بأن بريشيا روسو (1695-1740) ورث روحًا تُعرف باللغة التركية باسم عثمان بابا، والذي كان التجسيد الحقيقي لروح تسڤي.

حظيت هذه الادعاءات بالاهتمام وأدت إلى ظهور فرع القرهقاشي أو القونيوسو (اللادينو)، وهو الفرع الأكثر عددًا والأكثر صرامة في الدونمه.[9]

كان المبشرون من القرهقاشي أو القونيوسو نشطين في پولندا في النصف الأول من القرن الثامن عشر وقاموا بتدريس جاكوب فرانك (1726-1791)، الذي ادعى لاحقًا أنه ورث روح روسو.[بحاجة لمصدر] واصل فرانك تأسيس الحركة الفرانكية، وهي حركة شبطائية كاربوقراطيون جديدة مميزة في شرق أوروپا. وهناك مجموعة أخرى، وهي الليخلي، اليهود من أصل پولندي، الذين عاشوا في المنفى في سالونيك والقسطنطينية.[بحاجة لمصدر]

اقترح بعض المعلقين أن العديد من الأعضاء البارزين في حركة تركيا الفتاة، وهي حركة من الثوار المؤيدين للملكية الدستورية مناهضة للحكم المطلق، الذين أجبروا السلطان عام 1908 على إصدار دستور، كانوا من الدونمة.[10] في وقت تبادل السكان بين اليونان وتركيا عام 1923، حاول بعض الدونمه في سالونيك الاعتراف بهم كغير مسلمين لتجنب إجبارهم على مغادرة المدينة.[بحاجة لمصدر] كان أحد زعماء مؤامرة إزمير لاغتيال الرئيس مصطفى كمال باشا (أتاتورك) في إزمير بعد تأسيس الجمهورية التركية دونمًا يُدعى محمد جاويد،[11] عضو مؤسس جمعية الاتحاد والترقي ووزير المالية السابق في الدولة العثمانية.[12][13][14][15] بعد تحقيق حكومي، أُدين جاويد بك وأُعدم شنقًا في 26 أغسطس 1926 في أنقرة.[16] بعد تأسيس الجمهورية التركية عام 1923، كانت السياسات القومية التركية التي تبناها أتاتورك، والتي تركت الأقليات في مأزق، مصحوبة بدعاية معادية للسامية من قبل الناشرين القوميين في الثلاثينيات والأربعينيات.[17]

الأيديولوجيا

تدور أيديولوجية الدونمه في القرن السابع عشر بشكل أساسي حول الوصايا الثماني عشرة، وهي نسخة مختلفة من الوصايا العشر حيث يتم تفسير تحريم الزنا على أنه إجراء احترازي أكثر من كونه تحريماً، ومن المحتمل أن يتم تضمينه لشرح الأنشطة الجنسية المسقطعة للتكاليف عند الشبطائيين[بحاجة لمصدر]. وتتعلق الوصايا الإضافية بتحديد أنواع التفاعلات التي قد تحدث بين الدونمه والجاليات اليهودية والإسلامية. وكان أكثر قواعد التفاعل هذه أساسية هو تفضيل العلاقات داخل الطائفة على تلك التي خارجها وتجنب الزواج من اليهود أو المسلمين. وعلى الرغم من هذا، فقد حافظوا على علاقات مع الشبطائيين الذين لم يعتنقوا الإسلام وحتى مع الحاخامات اليهود، الذين كانوا يحسمون النزاعات المتعلقة بالشريعة اليهودية سراً.[9]

أما فيما يتعلق بالطقوس، فقد اتبع الدونمه التقاليد اليهودية والإسلامية على حد سواء، متنقلين بينهما حسب الضرورة من أجل الاندماج في المجتمع العثماني.[18] كان الدونمه مسلمون ظاهريًا ويهودًا شبطائيين سرًا، وكانوا يحتفلون بالمناسبات الإسلامية مثل شهر رمضان، لكنهم أيضًا حافظوا على طقوس الشبات، وعهد الختان، واحتفلوا بالأعياد اليهودية.[4] كان جزء كبير من طقوس الدونمه عبارة عن مزيج من عناصر مختلفة من القباله، الشبطائية، الشريعة التقليدية اليهودية، والتصوف.[19]

تطورت طقوس الدونمه مع نمو الطائفة وانتشارها. في البداية، كان الكثير من أدبياتهم مكتوبًا بالعبرية، لكن مع تطور المجموعة، حلت اللغة اللادينية محل العبرية وأصبحت ليس فقط اللغة العامية بل وأيضًا لغة الطقوس. وعلى الرغم من أن الدونمه انقسمت إلى عدة طوائف، إلا أن جميعهم اعتقدوا أن تسڤي هو المسيح اليهودي المنتظر وأنه كشف عن "التوراة الروحية" الحقيقية[9] حيث كان الدونمه يحتفلون بالأعياد المرتبطة بمراحل مختلفة من حياته وتاريخ اعتناقه الإسلام. واستنادًا جزئيًا على الأقل إلى الفهم القبالي للألوهية، اعتقد الدونمه أن هناك صلة ثلاثية بين الحضرات الإلهية، مما أدى إلى العديد من الصراعات مع الجاليات الإسلامية واليهودية على حد سواء. وكان المصدر الأكثر بروزًا للمعارضة من الديانات المعاصرة الأخرى هو الممارسة الشائعة لتبادل الزوجات بين أعضاء طائفة الدونمه.[9]

كان التسلسل الهرمي للدونمه قائمًا على تقسيمات الفروع. وكان فرع إزمير، التي تتألف من التجار والمثقفين، على رأس التسلسل الهرمي. وكان الحرفيون في الغالب من فرع قرهقاش في حين كانت الطبقات الدنيا في الغالب من اليعقوبيين. وكان لكل فرع صلاة خاص به، منظم في هيئة كحال أو جماعة.[9] كان هناك شبكة اقتصادية داخلية واسعة النطاق من الطبقة الدنيا تقدم الدعم للدونمه على الرغم من الاختلافات الأيديولوجية بين الفروع المختلفة.[20]

بعد إعلان استقلال إسرائيل عام 1948، هاجر عدد قليل فقط من عائلات الدونمه إلى إسرائيل.[21] في عام 1994، بدأ إيلگاز زورلو، وهو محاسب ادعى أنه من أصل دونمي من جهة والدته، في نشر مقالات في مجلات التاريخ كشف فيها عن هويته الدونميه التي أعلنها بنفسه وقدم الدونمه ومعتقداتهم.[22] وبما أن حاخام باشي والحاخامية الكبرى في إسرائيل لم يقبلا الدونمه كيهود دون اعتناق مطول لليهودية،[23][24] تقدم زورلو بطلب إلى المحكمة الابتدائية التاسعة بإسطنبول في يوليو 2000. وطلب تغيير انتمائه الديني في بطاقة هويته التركية من "مسلم" إلى "يهودي" وفاز بقضيته. وبعد فترة وجيزة، قبلته بيت دين التركية كيهودي.[25]

ومع ذلك، بما أنهم غير معترف بهم كيهود من قبل إسرائيل، فإن الدونمه غير مؤهلين للاستفادة بقانون العودة.[23] بالنسبة لـ قانون العودة الپرتغالي، فإن قرار الاعتراف بالدونمه كيهود أم لا تستعين به الجاليات اليهودية المحلية.[26] وضع الدونمه مشابه لوضع الفلاش مورا.

معاداة السامية والتشابكات السياسية المزعومة

تتركز معاداة السامية والشائعات التركية التي تعتمد عليها حول الدونمه.[27] وفقًا للمؤرخ مارك ديڤد باير، فإن هذه الظاهرة لها جذور عميقة في التاريخ العثماني المتأخر، واستمر إرثها من الاتهامات التآمرية طوال تاريخ الجمهورية التركية ولا يزال حيًا هناك حتى اليوم. تميل معاداة السامية الحديثة إلى تقديم اليهود كوحدة متجانسة منتشرة في كل مكان تعمل سراً عبر مجموعات عالمية متنوعة في السعي إلى السيطرة السياسية والاقتصادية العالمية عبر قنوات سرية. وباعتبارها طائفة شباطية سرية، كانت الدونمة دائمًا هدفًا سهلاً للمزاعم حول السيطرة السياسية اليهودية السرية والنفوذ الاجتماعي، سواء تم اتهامها بإثارة الاضطرابات السياسية ضد الوضع الراهن، أو اتهامها بتشكيل قبضة نظام قمعي على الوضع الراهن.[27]

إن تاريخ الدونمه من السرية اللاهوتية والطقوسية الشباطية التي تستند إلى التقاليد اليهودية، إلى جانب المراقبة العامة للإسلام، يجعل اتهامات السيطرة اليهودية السرية مناسبة، وفقًا لباير.[27] إن "اليهودي المتخفييون" أو "اليهود السريون" يحملون إذن معنى مزدوجاً، فهم يهود سريون ويهود يتصرفون سراً من أجل السيطرة؛ وهويتهم الدينية السرية في المقام الأول متوافقة، بالنسبة لمنظري المؤامرة، مع نفوذهم السري، وخاصة عندما لا يمكن تمييزهم عن المسلمين الأتراك العاديين الذين يقيمون في كل مكان، وكما يزعم باير، عندما يرى معادي السامية الحديث أن اليهودي بالضرورة "في كل مكان". قيل الدونمه كانوا في قلب ثورة تركيا الفتاة وإطاحة السلطان عبد الحميد الثاني وحل المؤسسة الدينية العثمانية وتأسيس جمهورية علمانية. صور المؤيدون للسلطان والمعارضون السياسيون الإسلاميون هذه الأحداث على أنها مؤامرة يهودية وماسونية عالمية نفذها الدونمه في تركيا. طرح الإسلاميون نظرية مؤامرة زعموا فيها أن أتاتورك كان دونميًا من أجل تشويه سمعته لأنهم عارضوا إصلاحاته، كما خلقوا العديد من نظريات المؤامرة الأخرى عنه.[27]

انظر أيضاً

- الله داد

- حالا

- كونڤرسو

- Neofiti

- سوبوتنيك

- فرانكية

- تاريخ اليهود في تركيا

- فلاش مورا

- نزاع برشلونة (1263)

- نزاع طرطوشة (1413–1414)

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ "Judaism – The Lurianic Kabbalah: Shabbetaianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 23 January 2020.

Rabbi Shabbetai Tzevi of Smyrna (1626–76), who proclaimed himself messiah in 1665. Although the "messiah" was forcibly converted to Islam in 1666 and ended his life in exile 10 years later, he continued to have faithful followers. A sect was thus born and survived, largely thanks to the activity of Nathan of Gaza (c. 1644–90), an unwearying propagandist who justified the actions of Shabbetai Tzevi, including his final apostasy, with theories based on the Lurian doctrine of "repair". Tzevi's actions, according to Nathan, should be understood as the descent of the just into the abyss of the "shells" in order to liberate the captive particles of divine light. The Shabbetaian crisis lasted nearly a century, and some of its aftereffects lasted even longer. It led to the formation of sects whose members were externally converted to Islam—e.g., the Dönmeh (Turkish: "Apostates") of Salonika, whose descendants still live in Turkey—or to Roman Catholicism—e.g., the Polish supporters of Jacob Frank (1726–91), the self-proclaimed messiah and Catholic convert (in Bohemia-Moravia, however, the Frankists outwardly remained Jews). This crisis did not discredit Kabbalah, but it did lead Jewish spiritual authorities to monitor and severely curtail its spread and to use censorship and other acts of repression against anyone—even a person of tested piety and recognized knowledge—who was suspected of Shabbetaian sympathies or messianic pretensions.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Gershom Scholem (2017). "Doenmeh". Jewish Virtual Library. American–Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

DOENMEH (Dönme), sect of adherents of Shabbetai Ẓevi who embraced Islam as a consequence of the failure of the Shabbatean messianic upheaval in the Ottoman Empire. After Shabbetai Ẓevi converted to Islam in September 1666, large numbers of his disciples interpreted his apostasy as a secret mission, deliberately undertaken with a particular mystical purpose in mind. The overwhelming majority of his adherents, who called themselves ma'aminim ("believers"), remained within the Jewish fold. However, even while Shabbetai Ẓevi was alive several leaders of the ma'aminim thought it essential to follow in the footsteps of their messiah and to become Muslims, without, as they saw it, renouncing their Judaism, which they interpreted according to new principles. Until Shabbetai Ẓevi's death in 1676 the sect, which at first was centered largely in Adrianople (Edirne), numbered some 200 families. They came mainly from the Balkans, but there were also adherents from İzmir, Bursa, and other places. There were a few outstanding scholars and kabbalists among them, whose families afterward were accorded a special place among the Doenmeh as descendants of the original community of the sect. Even among the Shabbateans who did not convert to Islam, such as Nathan of Gaza, this sect enjoyed an honorable reputation and an important mission was ascribed to it. Clear evidence of this is preserved in the commentary on Psalms (written c. 1679) of Israel Ḥazzan of Castoria.

Many of the community became converts as a direct result of Shabbetai Ẓevi's preaching and persuasion. They were outwardly fervent Muslims and privately Shabbatean ma'aminim who practiced a type of messianic Judaism, based as early as the 1670s or 1680s on "the 18 precepts" which were attributed to Shabbetai Ẓevi and accepted by the Doenmeh communities. [...] These precepts contain a parallel version of the Ten Commandments. However, they are distinguished by an extraordinarily ambiguous formulation of the commandment "Thou shalt not commit adultery," which approximates more to a recommendation to take care rather than a prohibition. The additional commandments determine the relationship of the ma'aminim toward the Jews and the Turks. Intermarriage with true Muslims is strictly and emphatically forbidden. - ^ أ ب ت ث Kaufmann Kohler; Henry Malter (1906). "Shabbetai Ẓevi". Jewish Encyclopedia. Kopelman Foundation.

At the command [of the sultan], Shabbetai was now taken from Abydos to Adrianople, where the sultan's physician, a former Jew, advised Shabbetai to embrace Islam as the only means of saving his life. Shabbetai realized the danger of his situation and adopted the physician's advice. On the following day [...] being brought before the sultan, he cast off his Jewish garb and put a Turkish turban on his head; and thus his conversion to Islam was accomplished. The sultan was much pleased, and rewarded Shabbetai by conferring on him the title (Mahmed) "Effendi" and appointing him as his doorkeeper with a high salary. [...] To complete his acceptance of Mohammedanism, Shabbetai was ordered to take an additional wife, a Mohammedan slave, which order he obeyed. [...] Meanwhile Shabbetai secretly continued his plots, playing a double game. At times he would assume the role of a pious Mohammedan and revile Judaism; at others he would enter into relations with Jews as one of their own faith. Thus in March 1668, he gave out anew that he had been filled with the Holy Spirit at Passover and had received a revelation. He, or one of his followers, published a mystic work addressed to the Jews in which the most fantastic notions were set forth, e.g., that he was the true Redeemer, in spite of his conversion, his object being to bring over thousands of Mohammedans to Judaism. To the sultan he said that his activity among the Jews was to bring them over to Islam. He therefore received permission to associate with his former coreligionists, and even to preach in their synagogues. He thus succeeded in bringing over a number of Mohammedans to his cabalistic views, and, on the other hand, in converting many Jews to Islam, thus forming a Judæo-Turkish sect (Dönmeh), whose followers implicitly believed in him [as the Jewish Messiah). This double-dealing with Jews and Mohammedans, however, could not last very long. Gradually the Turks tired of Shabbetai's schemes. He was deprived of his salary, and banished from Adrianople to Constantinople. In a village near the latter city he was one day surprised while singing psalms in a tent with Jews, whereupon the grand vizier ordered his banishment to Dulcigno, a small place in Albania, where he died in loneliness and obscurity.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Kohler, Kaufmann; Gottheil, Richard (1906). "Dönmeh". Jewish Encyclopedia. Kopelman Foundation. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

A sect of crypto-Jews, descendants of the followers of Shabbethai Ẓebi, living today mostly in Salonica, European Turkey: the name (Turkish) signifies "apostates." The members call themselves "Ma'aminim" (Believers), "Ḥaberim" (Associates), or "Ba'ale Milḥamah" (Warriors); but at Adrianople they are known as "Sazanicos" (Little Carps)—a name derived either from the fish-market, near which their first mosque is supposed to have been situated, or because of a prophecy of Shabbethai that the Jews would be delivered under the zodiacal sign of the fish. The Dönmeh are said to have originated with Jacob Ẓebi Querido, who was believed to have been a reincarnation of Shabbethai.

The community is outwardly Mohammedan (following the example set by Shabbethai); but in secret observes certain Jewish rites, though in no way making common cause with the Jews, whom they call "koferim" (infidels). The Dönmeh are evidently descendants of Spanish exiles. Their prayers, as published by Danon, are partly in Hebrew (which few seem to understand) and partly in Ladino. They live in sets of houses which are contiguous, or which are secretly connected; and for each block of houses there is a secret meeting-place or "kal" ("ḳahal"), where the "payyeṭan" reads the prayers. Their houses are lit by green-shaded lamps to render them less conspicuous. The women wear the "yashmak" (veil); the men have two sets of names: a religious one, which they keep secret, and a secular one for purposes of commercial intercourse. They are assiduous in visiting the mosque and in fasting during Ramadhan, and at intervals they even send one of their number on the "ḥajj" (pilgrimage) to Mecca. But they do not intermarry with the Turks.

They are all well-to-do, and are prompt to help any unfortunate brother. They smoke openly on the Sabbath day on which day they serve the other Jews, lighting their fires and cooking their food. They work for the Turks when a religious observance prevents other Jews from doing so, and for the Christians on Sunday. They are expert "katibs" or writers, and are employed as such in the bazaars and in the inferior government positions. They have the monopoly of the barber-shops. The Dönmeh are divided into three subsects, which, according to Bendt, are: the Ismirlis, or direct followers of Shabbethai Ẓebi of Smyrna, numbering 2,500; the Ya'ḳubis, or followers of Jacob Querido, brother-in-law of Shabbethai, who number 4,000; and the Kuniosos, or followers of Othman Baba, who lived in the middle of the eighteenth century. The last named sect numbers 3,500. Each subsect has its own cemetery. - ^ Sean McMeekin, The Berlin-Baghdad Express p.75

- ^ أ ب Abraham J. Karp (2017). ""Witnesses to History": Shabbetai Zvi – False Messiah (Judaic Treasures)". Jewish Virtual Library. American–Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). Archived from the original on 16 October 2017.

Born in Smyrna in 1626, he showed early promise as a Talmudic scholar, and even more as a student and devotee of Kabbalah. More pronounced than his scholarship were his strange mystical speculations and religious ecstasies. He traveled to various cities, his strong personality and his alternately ascetic and self-indulgent behavior attracting and repelling rabbis and populace alike. He was expelled from Salonica by its rabbis for having staged a wedding service with himself as bridegroom and the Torah as bride. His erratic behavior continued. For long periods, he was a respected student and teacher of Kabbalah; at other times, he was given to messianic fantasies and bizarre acts. At one point, living in Jerusalem seeking "peace for his soul," he sought out a self-proclaimed "man of God," Nathan of Gaza, who declared Shabbetai Zvi to be the Messiah. Then Shabbetai Zvi began to act the part [...] On September 15, 1666, Shabbetai Zvi, brought before the sultan and given the choice of death or apostasy, prudently chose the latter, setting a turban on his head to signify his conversion to Islam, for which he was rewarded with the honorary title "Keeper of the Palace Gates" and a pension of 150 piasters a day. The apostasy shocked the Jewish world. Leaders and followers alike refused to believe it. Many continued to anticipate a second coming, and faith in false messiahs continued through the eighteenth century. In the vast majority of believers revulsion and remorse set in and there was an active endeavor to erase all evidence, even mention of the pseudo messiah. Pages were removed from communal registers, and documents were destroyed. Few copies of the books that celebrated Shabbetai Zvi survived, and those that did have become rarities much sought after by libraries and collectors.

- ^ Türkay S. Nefes (September 2015). "Scrutinizing impacts of conspiracy theories on readers' political views: a rational choice perspective on anti-semitic rhetoric in Turkey". The British Journal of Sociology. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. 66 (3): 557–575. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12137. PMID 26174172.

- ^ رفعت بالي (2012). Model Citizens of the State: The Jews of Turkey During the Multi-party Period. Lexington Books. p. 18.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Scholem, Gershom (1974). Kabbalah. New York, NY: Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Company.

- ^ Adam Kirsch (15 February 2010). "The Other Secret Jews". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ Andrew Mango, Atatürk, John Murray, 1999, pp. 448–453

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 215.

- ^ Ilgaz Zorlu, Evet, Ben Selânikliyim: Türkiye Sabetaycılığı, Belge Yayınları, 1999, p. 223.

- ^ Yusuf Besalel, Osmanlı ve Türk Yahudileri, Gözlem Kitabevi, 1999, p. 210.

- ^ Rıfat N. Bali, Musa'nın Evlatları, Cumhuriyet'in Yurttaşları, İletişim Yayınları, 2001, p. 54.

- ^ "Javid (Cavid) Bey, Mehmed". Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "The journal İnkılâp and the appeal of antisemitism in interwar Turkey" by Alexandros Lamprou, Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 58, 2022, pp. 32-47

- ^ Baer, Marc. (2007). "Globalization, Cosmopolitanism, and the Dönme in Ottoman Salonica and Turkish Istanbul." Journal of World History. 18. no. 2: 141–170. doi: 10.1353/jwh.2007.0009. [1]

- ^ Marc Baer, "Dönme (Ma'aminim, Minim, Shabbetaim)," Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Executive Editor Norman A. Stillman. Brill Online, 2013. Reference. University of Maryland. 7 March 2013

- ^ Weiker, Walter F. (1992). "Ottomans, Turks, and the Jewish Polity: A History of the Jews of Turkey." Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- ^ "Doenmeh". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Bali 2010, p. 37.

- ^ أ ب Yardeni, Dan (18 August 2013). "A Scapegoat For All Seasons: The Dönmes or Crypto-Jews of Turkey by Rifat Bali". eSefarad (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Jewish History / Waiting for the Messiah – Haaretz – Israel News". 19 May 2009. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Bali 2010, p. 42.

- ^ "The Rotten Saga of Roman Abramovich's Portuguese Citizenship, and Its Repercussions". Haaretz (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Marc David Baer (2013). "An Enemy Old and New: The Dönme, Anti-Semitism, and Conspiracy Theories in the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic". Jewish Quarterly Review. 103 (4): 523–555. doi:10.1353/jqr.2013.0033. S2CID 159483845 – via Project MUSE.

المراجع

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (26 June 2018), Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide, Princeton University Press (published 2018), ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7

- Bali, Rıfat N. (24 June 2010). "1. A Scapcgoat for All Seasons: The Dônmes or Crypto-Jews of Turkey". A Scapegoat For All Seasons: The Dönmes or Crypto - Jews of Turkey (in الإنجليزية). Gorgias Press. pp. 17–88. doi:10.31826/9781463225568-004. ISBN 978-1-4632-2556-8.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

قراءات إضافية

- Baer, Marc David (2010). The Dönme : Jewish converts, Muslim revolutionaries, and secular Turks. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7256-3. OCLC 589169152.

- Landau, Jacob M. (2007). "The Dönmes: Crypto-Jews under Turkish Rule". Jewish Political Studies Review. 19 (1/2): 109–118. ISSN 0792-335X.

- Sisman, Cengiz (20 August 2015). The Burden of Silence: Sabbatai Sevi and the Evolution of the Ottoman-Turkish Donmes (in الإنجليزية). Oxford University Press.

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- Articles containing التركية العثماثية (1500-1928)-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2014

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- متحولون من اليهودية

- يهودية خفية

- جماعات تدعي نسباً يهودياً

- تاريخ تركيا

- الإسلام في تركيا

- اليهود واليهودية في تركيا

- الإسلام واليهودية

- الدين في تركيا

- شبطائيون

- المجتمع التركي

- كلمات وعبارات تركية