أرض بلا صاحب

أرض بلا صاحب (باللاتينية: Terra nullius ؛ /ˈtɛrə.nʌˈlaɪəs/، وتُجمَع terrae nullius) هي تعبير لاتيني مشتق من القانون الروماني تعني "أرض بلا صاحب"،[1] which is used in international law to describe territory which has never been subject to the sovereignty of any state, or over which any prior sovereign has expressly or implicitly relinquished sovereignty. Sovereignty over territory which is terra nullius may be acquired through occupation,[2] (see reception statute) though in some cases doing so would violate an international law or treaty.

الأراضي الحالية بلا صاحب

بير طويل

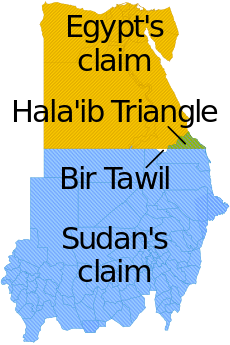

Between Egypt and Sudan is the 2،060 km2 (795 sq mi) landlocked territory of Bir Tawil, which was created by a discrepancy between borders drawn in 1899 and 1902. One border placed Bir Tawil under Sudan's control and the Hala'ib Triangle under Egypt's; the other border did the reverse. Both countries assert the border that lets them claim Hala'ib, which is significantly larger and next to the Red Sea, with the side effect that Bir Tawil is unclaimed by either nation. The area is, however, under the de facto control of Egypt, although it is not shown on official Egyptian maps.[3] Bir Tawil has no settled population.

In June 2014, Jeremiah Heaton planted a flag in Bir Tawil to claim the region as a new sovereign state, the Kingdom of North Sudan,[4][5][6][7] and subsequently announced the establishment of self-styled "embassies" elsewhere in the world;[8] no governmental entity has recognized this claim.

أراضي على طول نهر الدانوب

مدخل ديكسون

الولايات المتحدة and Canada define the maritime boundary through the Dixon Entrance in different ways. The boundary was originally agreed upon in 1825 between Russia and the UK, but the treaty wording was insufficiently precise. To resolve the ambiguity, an arbitration tribunal in 1903 issued a decision defining the Alaska/Canada boundary, which included marking a straight line from Cape Muzon to the entrance of Portland Canal, known as the "A–B" line.[9][10] The court specified the initial boundary point (Point "A") at the northern end of Dixon Entrance[11] and also designated Point "B" 72 NM to the east.[12] Canada's position is that "A" and "B" are part of the arbitrated boundary delimitation, thus rendering nearly all of Dixon Entrance as internal waters. The U.S. does not recognize the "A–B" line as an official boundary, instead regarding it as allocating sovereignty over the land masses within the Dixon Entrance,[9] with Canada's land south of the line. The U.S. regards the waters as subject to international marine law, and in 1977 it defined an equidistant territorial line that is mainly to the south of the "A–B" line, but not entirely. North of Dundas Island, the equidistance line swings north of the "A–B" line.[9] The intersecting lines create four separate water areas with differing claim status. The two areas south of the "A–B" line are claimed by both countries. The other two water areas are north of the "A–B" line and are not claimed by either country. The two unclaimed areas are about 72 km2 and 1.4 km2 in size.[9]

المناطق غير المطالَب بها في أنتارتيكا

البحر الدولي

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982, the international waters and international seabed are treated under the common heritage of mankind principle by the signatories of the convention.

الأجرام السماوية

According to the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means that fits. For the signatories of the treaty, celestial bodies are treated, de jure, under the common heritage of mankind principle.[13]

حدود الاختصاص والسيادة الوطنية

The principal treaties defining sovereignty beyond land territory are the Outer Space Treaty and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. They confirm the full national jurisdiction over the coastal waters (internal and territorial) and over the continental shelf underground. There are limitations that allow foreign vessels the right of passage and for foreign states to lay pipelines and cables in the territorial waters, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf surface. Exploitation of marine life and mineral resources in these areas is a reserved right of the coastal state. Exploitation of mineral resources in the extended continental shelf is a reserved right of the coastal state, but it must pay tax on these activities to the International Seabed Authority (UNCLOS, Art. 82). The archipelagic waters are covered by a special hybrid regime with rules regarding territorial and internal waters.

On vessels, spacecraft and structures in places with international jurisdiction or terra nullius, the general rule is that the operator state of the vessel is responsible for it and regulates laws there. Additionally, the crew are subject to the laws of the state of their citizenship [محل شك]. Earth orbital slots are the only type of extraterrestrial real estate recognised by law and are allocated by the International Telecommunication Union (part of the نظام الأمم المتحدة).

There are some undefined limits for the application of jurisdiction and sovereignty:

- The boundary between outer space and airspace is not defined. In common parlance, the خط كارمان (100 km) is generally recognized as the boundary between airspace and outer space, but this definition is not explicitly recognized in any treaty.

- UNCLOS commission is defining the limits of the extended continental shelf.

- UNCLOS is inconclusive about the status of airspace over the contiguous zone (whether it is treated as international airspace or some special rules apply there).[بحاجة لمصدر]

- There is no defined bottom underground limit for jurisdiction and sovereignty, because in practice there are no cases where it is relevant and the current technology level does not allow the reaching of depths where conflicting claims could be made (there are some disputes about border underground oil and gas reserve reservoirs, but their depth is not enough so that the curvature of the Earth and the exact line of the underground border between the states matters).

The current entities that exercise jurisdiction and sovereignty rights are:

- the 193 United Nations member states;

- القاصد الرسولي و فلسطين، the United Nations observer states;

- جزر كوك and Niue, associated with and represented in foreign affairs by New Zealand;

- the 17 non-self-governing territories with recognised right for self-determination by the United Nations (currently under jurisdiction of 5 UN members);

- the 10 states with limited recognition;

| الفضاء الخارجي (بما في ذلك مدارات الأرض؛ القمر and other celestial bodies, and their orbits) | |||||||

| national airspace | territorial waters airspace | contiguous zone airspace[بحاجة لمصدر] | international airspace | ||||

| land territory surface | internal waters surface | territorial waters surface | contiguous zone surface | سطح المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة | سطح المياه الدولية | ||

| مياه داخلية | territorial waters | Exclusive Economic Zone | المياه الدولية | ||||

| land territory underground | Continental Shelf surface | extended continental shelf surface | سطح قاع البحر الدولي | ||||

| الرصيف القاري تحت الأرض | extended continental shelf underground | قاع البحر الدولي تحت الأرض | |||||

انظر أيضاً

- Aboriginal land claims

- أستراليا

- Land claim

- Manifest destiny

- No man's land

- Neutral territory

- Res nullius (original and broader formulation in law)

- Uncontacted people

- Uti possidetis

الهامش

- ملاحظات

- ^ "Definition of terra nullius- English Dictionary". Allwords.com. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "New Jersey v. New York, 523 US 767 (1998)". US Supreme Court. 26 May 1998. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

Even as to terra nullius, like a volcanic island or territory abandoned by its former sovereign, a claimant by right as against all others has more to do than planting a flag or rearing a monument. From the 19th century the most generous settled view has been that discovery accompanied by symbolic acts give no more than "an inchoate title, an option, as against other states, to consolidate the first steps by proceeding to effective occupation within a reasonable time.8 I. Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law 146 (4th ed.1990); see also 1 C. Hyde, International Law 329 (rev.2d ed.1945); 1 L. Oppenheim International Law §§222-223, pp. 439–441 (H. Lauterpacht 5th ed.1937); Hall A Treatise on International Law, at 102–103; 1 J. Moore, International Law 258 (1906); R. Phillimore, International Law 273 (2d ed. 1871); E. Vattel, Law of Nations, §208, p. 99 (J. Chitty 6th Am. ed. 1844).

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. CIA World Factbook 2009 MobileReference, 2009. ISBN 1607783339

- ^ Gibson, Allie Robinson (10 July 2014). "Abingdon man claims African land to make good on promise to daughter". Bristol Herald Courier. Bristol, Virginia: Berkshire Hathaway. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ Najarro, Ileana (12 July 2014). "Va. man plants flag, claims African country, calling it 'Kingdom of North Sudan'". Washington Post. Washington, DC. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ Ensor, Josie (14 July 2014). "US father takes unclaimed African kingdom so his daughter can be a princess". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Mapping micronations". Al Jazeera. 14 August 2014. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

Passports, currencies and flags: We discuss what it takes to create your own country.

- ^ "Embassies – Kingdom of North Sudan". Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Gray, David H. (Autumn 1997). "Canada's Unresolved Maritime Boundaries" (PDF). IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin. pp. 61–63. Retrieved 2015-03-21.

- ^ "International Boundary Commission definition of the Canada/US boundary in the NAD83 CSRS reference frame". Retrieved 2015-03-21.

- ^ White, James (1914). Boundary Disputes and Treaties. Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Company. pp. 936–958.

- ^ Davidson, George (1903). The Alaska Boundary. San Francisco: Alaska Packers Association. pp. 79–81, 129–134, 177–179, 229.

- ^ "The Moon: A GIANT LEAP FOR MANKIND". TIME Magazine. 25 July 1969. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ببليوگرافيا

- Connor, Michael. "The invention of terra nullius", Sydney: Macleay Press, 2005.

- Culhane, Dara. The Pleasure of the Crown: Anthropology, Law, and the First Nations. Vancouver: Talon Books, 1998.

- Lindqvist, Sven. Terra nullius. A Journey through No One's Land. Translated by Sarah Death. Granta, London 2007. Pbk 2008. The New Press, New York 2007. Details here

- Rowse, Tim. "Terra nullius" – The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Ed. Graeme Davison, John Hirst and Stuart Macintyre. Oxford University Press, 2001.

وصلات خارجية

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Social Justice Reports, 1994–2009 http://www.humanrights.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/ and Native Title Reports, 1994–2009 http://www.humanrights.gov.au/social_justice/nt_report/index.html

- A History of the concept of "Terra Nullius" The University of Sydney

- Governor Burke's 1835 Proclamation of terra nullius NSW Migration Heritage Centre – Statement of Significance

- Veracini L, An analysis of Michael Conner's denial of terra nullius (The Invention of Terra Nullius)

- Terror Nullius <http://www.wulfdhund.de/rassismusanalyse/?Ergaenzungen:Australien>

- [1] High Court of Australia – MABO AND OTHERS v. QUEENSLAND (No. 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 F.C. 92/014

- [2] High Court of Australia – The Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland & Ors; The Thayorre People v The State of Queensland & Ors [1996] HCA 40 (23 December 1996)

- [3] 1975 International Court of Justice – Advisory Opinion regarding Western Sahara

- "History before European Settlement" Parliament of New South Wales

- material on terra nullius – NSW Primary School curriculum

- [4] R. v. Boatman or Jackass and Bulleye – Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788–1899 (Published by the Division of Law, Macquarie University)