جهاد الخوجة الآفاقي

| جهاد الخوجة الآفاقي | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

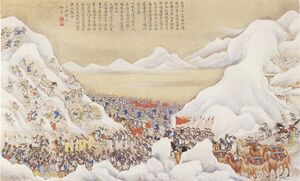

انتصار التشينگ على الآفاقي في قشغر | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

Qing Dynasty Qara Taghliqs (Ishāqis Khojas) Hunza Princely State[1] |

خانية خوقند Aq Taghliqs (Āfāqī Khojas) | ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

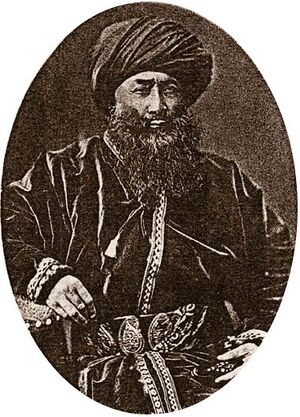

Daoguang Emperor Changling[3] مير غضنفر[4] |

جهانگير خوجة يوسف خوجة Katta Tore والي خان Kichik Khan توكل توره بزرگ خان | ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

|

Eight Banners Manchu Bannerman Green Standard Army Han Chinese Militia Hui Chinese Militia Ishāqis Turkic Followers Hunza Burusho Soldiers |

Āfāqī Turkic Followers Dolan people[5] | ||||||

In 1759, the Qing dynasty of China defeated the Dzungar Khanate and completed the conquest of Dzungaria. Concurrent with this conquest, the Qing occupied the Altishahr region of Eastern Turkestan which had been settled by Muslims who followed the political and religious leadership of Afaq Khoja.[6][7]

After the Qing conquest, the Chinese began to incorporate Altishahr and the Tarim Basin into their empire. The territory along with Dzungaria came to be known as Xinjiang. Although the followers of Afaq Khoja known as the Āfāqī Khojas resisted Qing rule, their rebellion was put down and the khojas were removed from power.[8]

Beginning at that time and lasting for approximately one hundred years, the Āfāqī Khojas waged numerous military campaigns as a part of a holy war in an effort to retake Altishahr from the Qing.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية الخوجة والغرماء

The Khojas of Central Asia were a Naqshbandī Sufi lineage founded by Ahmad Kāsānī (1461-1542), known as Makhdūm-i-Azam or the "Great Master". After his death, the followers of Ahmad Kāsānī known as Makhdūmzādas, split into two factions, one led by Afaq Khoja and another by Ishāqi Khoja.[9]

The followers of Ishāqi Khoja were the first to settle in Eastern Turkestan and became known as the Ishāqis or the Qara Taghliqs ("Black Mountaineers"). The Āfāqī Khojas followed the Ishāqi Khojas into Eastern Turkestan settling in Yarkand where they became known as the Āfāqīs or Aq Taghliqs ("White Mountaineers").

The region was under Yarkent Khanate up until late-1600s, at which point it was conquered by Dzungar Khanate. For the 80 years until the Qing conquest, these two khoja factions governed the Altishahr on behalf of Dzungar Khanate including the six major cities (Aqsu, Kashghar, Khotan, Ush Turfan, Yangihissar, and Yarkand) bordering the Tarim Basin.[7] During these times, the two clans competed as rivals and generally treated each other with animosity.[10]

Just before the Qing conquest, the Ishàqís held control of Eastern Turkestan, although the populace was generally calling for change in favor of rule by the Āfāqī Khojas or even the Qing. In 1755–1756, Jahān Khoja and Burhān al-Dīn Khoja, two sons of an exiled Āfāqī Khoja leader, who supported Qing in its conquest of Dzungar Khanate, retook power in Altishahr. The restoration of Āfāqī power in the region ended quickly, however, as the two brothers were easily defeated by the Qing in 1759 and later executed.

At that time, the Altishahr region of Eastern Turkestan became part of a fragile Chinese frontier governed by Manchu governors and Turkestani officials including supporters of the Ishāqis. While some Āfāqī families remained in the conquered territory others relocated to Khoqand where they could hide, regroup, and strike back at the Qing. Khoqand, as so, would suddenly find itself involved in Āfāqī Khojas military expeditions aimed at the Chinese.[9]

Conduct of the Qing

During the time prior to the initiation of a holy war, animosity and hatred between the resident Muslims and the Qing grew as the result of a number of incidents and the conduct of the Qing.

In the first years after the conquest, local officials appointed by the Qing including ‘Abd Allah, the Hakim Beg of Ush Turfan, used their positions to extort money from the local population. Also during this time, the Qing superintendent Sucheng and his son were abducting Muslim women and holding them captive for months during which time the women were gang-raped. Such activities so angered the local Muslim population that it was reported that "Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on [Sucheng and son's] hides and eat their flesh."

As a result, in 1765 when Sucheng commandeered 240 men to take official gifts to Peking, the enslaved porters and the townspeople revolted. ‘Abd Allah, Sucheng, the garrisoned Qing force and other Qing officials, were slaughtered and the rebels took command of the Qing fortress. In response to the revolt, the Qing brought a large force to the city and besieged the rebels in their compound for several months until they surrendered. The Qing then cruelly retaliated against the rebels by executing over 2,000 men and exiling some 8,000 women. This uprising is known today as the Ush rebellion.[11][12][13][14]

During this period a problem greater than such an isolated armed rebellion was the general conduct of the Qing occupiers relative to Muslim women. Garrisoned Qing forces were not permitted to bring their family members to this faraway frontier. As a result, Qing soldiers sought female companionship with Muslim women despite prohibition by statute. Although some marriages did occur, illicit sex and prostitution were more common. Either women were brought into the fortresses at night or the soldiers spent their nights in the cities.

In addition, Qing officials used the power of their positions to exploit Muslim women in a manner similar to the kinds of things Sucheng had done in Ush Turfan. In 1807, Yu-qing the superintendent of Karashahr was accused of a series of abuses. Another Qing official, Bin-jing, was accused of committing a number of crimes during 1818-1820, one of which "dishonored" and caused the death of the daughter of the political advisor and elder of Khoqand.

Although the details of Bin-jing's crimes were suppressed to prevent further discord, the Muslim population during these times was quite aware and quite angered with the on-going fraternization that occurred between the Qing and Muslim women.[15]

التجريدات العسكرية بدعم من خوقند

Āfāqī Khoja challenge to Qing authority first emerged in 1797 when Sarimsaq, son of Burhān al-Dīn Khoja, attempted to launch a campaign to retake Kashghar but was stopped Narbuta Biy, the ruler of Khoqand.[16]

Attacks on the Qing began in earnest approximately twenty years later in 1820. At that time, Jāhangīr Khoja, the son of Sarimsaq, proposed to the ruler of Khoqand, Umar Khan, that they join as allies and launch a holy war against the Qing.[17] When the proposal was rejected by Umar Khan, Jāhangīr independently led some 300 soldiers on a raid to capture Kashghar. Jāhangīr's forces clashed with the Qing, but were forced to end the expedition even before reaching the gates of the Gulbagh fortress near Kashghar.[18]

In 1825, Jāhangīr and his guerilla force ambushed and killed most every member of a small Chinese detachment. This small victory caused the local tribesmen to rally to Jāhangīr's support and shortly thereafter Jāhangīr attacked the city of Kashghar and executed the governor, a Turki. The Chinese force assigned to the area was too weak to stop the attack which expanded into a general revolt in the cities of Yangihissar, Yarkand, and Khotan where Chinese civilians caught outside the city walls were slain.[19]

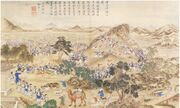

In 1826, Jāhangīr gathered another force of Qirghiz tribesmen, Kashgharians, and Khoqandian supporters and made plans for another attack on Kashghar. In the summer, the attack was launched, the city of Kashghar was captured, and the Gulbagh fortress was sieged. As in the prior year, the success of the campaign caused a general rebellion to erupt.

When the khojas attacked, the Qing had the support of the Hui merchants along with the Ishāqi Khojas who opposed the "debauchery" and "pillage" of the Āfāqī under Jāhangīr.[20][21] In addition, the Dungans assisted the Qing by serving in the Green Standard Army and as a part of the merchant militia that defended Kashghar and Yarkand.[22] In all such cases, this armed citizenry helped the Qing oppose Jāhangīr's attacks.

Meanwhile, in Khoqand, the ruler, Madali Khan, watched the activities close to his border and made the decision to join the holy war in support of Jāhangīr in order to protect Khoqand trade and commerce in the region. When Jāhangīr asked for assistance in capturing the Gulbagh fortress, Madali Khan led a Khoqand army of 10,000 to Kashghar. After participating personally in the battle for 12 days, Madali Khan returned home but left part of the Khoqandian force in Jāhangīr's command. On August 27 after the Qing had exhausted their food supply, the Gulbagh fortress surrendered to Jāhangīr. That summer Jāhangīr also successfully captured Yangihissar, Yarkand, and Khotan.[23]

The Qing responded in the spring of 1827 by sending an expeditionary force of more than 20,000 soldiers to combat the Āfāqī Khoja and by the end of March had recaptured all of their lost territory. Jāhangīr was captured and taken to Peking where he was ultimately executed by slicing (Lingchi).[24]

To protect and defend Altishahr from future attacks, the Qing increased troop levels in the territory, rebuilt the westernmost cities, and constructed stronger fortifications. Trade restrictions and boycotts were imposed against Khoqand for participating in the holy war and for allowing the Āfāqī to take refuge in Khoqand.[25]

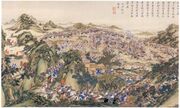

As the Qing were undertaking these activities in 1828–1829, Yusuf Khoja, the older brother of Jāhangīr Khoja, continued the Āfāqīs efforts to regain their lost homeland and approached the ruler of Khoqand for assistance just as his brother had done eight years earlier. Although, Madali Khan, who continued to rule Khoqand, really didn't desire to provoke the Qing, Khoqand was feeling the impact of the economic sanctions that had been imposed and felt that he had little to lose if he went to war against the Qing.

As such, Madali Khan supported the continuation of the holy war and allowed his highest military leaders, including Haqq Quli, the overall Commander of the army, to lead a large force against the Qing. Kashghar was easily occupied by September 1830 and the invaders immediately began a siege of the Gulbagh fortress. While the Khoqandians assaulted the Gulbagh fortress, Yusuf Khoja took a large force in an attempt to capture Yarkand.[26][27]

At Yarkand, Chinese merchants and the Qing military declined to battle openly, taking cover inside fortifications and killing Khoqandi troops from a distance with guns and cannons. Yarkand's Turkic Muslims also helped the Qing defend against the invaders.[28]

Over the next three months, neither the Khoqandian army nor Yusuf Khoja and his partisans were able to make any further conquests. No support of any kind was received from the populace and no major rebellion supported the expedition. Eventually a Qing relief force of 40,000 arrived. By the end of December 1830, the Khoqandian army and Yusuf Khoja had retreated back to Khoqand.[29]

Rather than punish Khoqand for the invasion of 1830, the Qing realized that their former approach of trade sanctions and restrictions was ineffective at stabilizing the territory and preventing conflict. As a result, the Qing entered into an agreement with Khoqand in 1832 that normalized the relationship between the two countries first by pardoning the Kashgharians living in exile in Khoqand and the Kashgharians living in Altishahr who had supported the holy war. The Qing then compensated Khoqandi merchants for their merchandise and property losses. With regard to commerce, the Qing removed the trade sanctions that they had put in place and began treating Khoqand as a favored trading partner with special privileges related to taxes, duties and tariffs.[30]

Military expeditions conducted independently

After the agreement of 1832 was implemented, Khoqand benefited economically from the new relationship with the Qing. As a result, Khoqand had a shared interest in keeping peace in the region and no longer supported the Āfāqī Khoja in their holy war. This ended all large scale khoja holy war military operations for a period of approximately 14 years. Only after 1846, when both Khoqand and China weakened economically due to revolutions, wars, and natural disasters, did the Āfāqīs reignite their efforts to regain Altishahr.

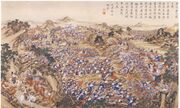

In August 1847, the sons and grandsons of Jāhangīr Khoja and his two brothers including Katta Tore, Yusuf Khoja, Wālī Khān, Tawakkul Tore, and Kichik Khan took advantage of the weakness of the Qing garrisons in Altishahr and crossed the border with a large force to attack Kashghar. [31] The raid was undertaken without the knowledge or assistance of Khoqand and later became known as the 1847 Holy War of the Seven Khojas.

The city of Kashghar was taken in less than a month after which the Qing fortresses in Kashghar and Yangihissar were besieged. The Qing fortresses held strong, however, and the excesses of the Āfāqī Khoja invaders alienated the citizens to such an extent that no support was received from the local Muslim community and no popular uprising occurred as it had in previous raids. To the citizens of the cities attacked, the invaders seemed like Khoqandi agents rather than spiritual liberators.[31]

In November, the Chinese were able to assemble a relief force and ultimately defeat the khojas in battle at Kok Robat near Yarkand. After the battle, the khojas collapsed and fled back to Khoqand.[32]

Throughout the 1850s additional invasions were undertaken independently by the khojas. Despite repeated defeats, the khojas continued to fight for their ancestral claim on Altishahr. The raids seem to become a regular feature of the region's politics during these years and included an invasion in 1852 led by Dīvān Quli and Wālī Khān; an invasion of 1855 led by Husayn Īshān Khwāja; and an invasion in 1857 led by Wālī Khān.

Wālī Khān was successful in capturing Kashghar in 1857 and holding the throne as Amir for approximately three months. In capturing the city, Wālī Khān had the support of the local population at the outset but lost favor for his harsh, tyrannical leadership and the imposition and strict enforcement of dress codes, religious customs and traditions.[33][34] During his short reign, Wālī Khān also gained notoriety when he infamously killed the German explorer Adolf Schlagintweit for no apparent reason.[35] Ultimately, Wālī Khān was abandoned by his supporters because of his cruelty and defeated by a Qing army.[36]

Compared with the invasions undertaken in 1826 and 1830, the raids of the 1850s lacked any formal state support on the part of Khoqand. In each case, the raids were carried out in an independent manner. After the raid of Husayn Īshān Khwāja and Wālī Khān in 1855, the Qing court formally investigated the invasion and concluded that the raid was not sponsored by Khoqand. As further proof of non-complicity on the part of Khoqand, the ruler of Khoqand, Khudàyàr Khàn, attempted to execute Wālī Khān in 1855 for massacring Muslins during the raid and ordered that surveillance be placed in the future on khoja leaders.[34]

The raids of the khojas in the 1850s ended time and again in failure ultimately because they were unable to create and lead a successful revolt with the support of the Muslim citizenry in both Khoqand and Altishahr.

نهاية الجهاد

In the 1860s great changes occurred in China and Altishahr that eventually نهاية جهاد الخوجة الآفاقي.

As the decade of the 1860s opened, the Qing economy and military continued to be strained by two major internal revolutions, the Taiping Rebellion and the Nian Rebellion. Both of these revolutions had been on-going for nearly ten years and had forced the Qing to reduce their logistical support and military strength in Altishahr.[37]

Added to the instability in China, fighting between the Dungans and the Han Chinese broke out in the summer of 1862 in the central Chinese Province of Shensi. The fighting grew and became known over time as the Dungan Revolt. As the Qing brought the Taiping army to Shensi to deal with the rebels, the authorities suggested that the Han organize formal militia units to protect themselves. Afraid that the Dungans would ally with the Taiping army against them, the Han militias began to slaughter the Dungans.[38]

The Dungan Revolt rapidly spread throughout Shensi and Kansu provinces. The Qing were not able to get control of the situation in central China until 1864 after the arrival of To-lung-a as the imperial commissioner and military leader. By March 1864, To-lung-a had recaptured most of Shensi province forcing the Dungan militias west into Kansu.[39]

As the Dungan Revolt took place, the Qing worried about the repercussions in Altishahr and ultimately they issued orders to disarm the Dungan soldiers in the Qing army and to execute suspicious individuals.[40] Concerned about such actions and attempting to rally support, the Dungans fighting the Qing in the rebellion issued warnings of an impending Qing massacre of Muslims throughout China.[41]

Such warnings spread west to Altishahr and were responsible among other grievances for the start of a Muslim rebellion that began in June 1864 when a group of Dungans in the small town of Kucha set fire to a marketplace and began killing those whom they considered infidels. The violence escalated and others Muslims joined in the rebellion. The small Qing garrison attempted to stop the violence but was defeated.[42]

By the end of June, armed attacks against the Qing authorities in Yarkand and Kashghar had begun. By the end of July similar rebellions had started in Aqsu, Urumchi, and Ush Turfan.[43]

Although the revolts in each case were initiated by the Dungans, other Muslims were quick to join the rebellion. Even though the Dungan Revolt was not a war of religion, the revolt in Altishahr that was ignited by the Dungans grew into a holy war. In Altishahr, individuals of different ethnicities, tribal affiliations, social backgrounds and classes united as Muslims and rebelled against the Qing regime. The motivations of the Altishahr revolutionaries differed in many cases but beginning at this time in 1864 virtually the entire Muslim population in Altishahr stood together against the infidel Qing rule. As so, the 1864 rebellion which started as a Dungan revolt led to a general widespread Muslim rebellion.[44]

As the Dungans and their Turkic Muslim allies fought for control of the city of Kashghar, requests for aid were made to the ruler of Khoqand, ‘Ālim Quli, and to the Āfāqī Khoja. In response, an expedition led by the renown Khoqandi military commander Ya‘qūb Beg was sent from Khoqand to Kashghar in late 1864. Included as a member of the small force sent to Kashghar was Buzurg Khan, the son of famed Āfāqī leader Jāhangīr Khoja.[45][46]

Over the next eight months, Ya‘qūb Beg led a coalition of Kyrgyz and Qipchaq tribesmen along with Badakhshi mountaineers and captured Kashghar, Yangihissar, and Yarkand.[47] By the spring of 1866, Ya‘qūb Beg had consolidated his powerbase and overcome Āfāqī khoja challenges from Wālī Khān and Buzurg Khan effectively ending the Āfāqī khoja holy war for Altishahr.[48]

Ya‘qūb Beg went on first to capture Khotan and Kucha in 1867 and then Urumchi and Ush Turfan by the end of 1870. The Qing were expelled from Central Asia and Ya‘qūb Beg ruled an independent Muslim state consisting of the entirety of Altishahr until 1877 when Qing General Zuo Zongtang completed the recapture of Altishahr and occupied Kashghar.[49]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الذكرى

During the reign of Ya‘qūb Beg many khoja religious leaders lost their influence. Many others were executed. After the Qing reconquered the region in 1877, the khoja ceased to be a group that exercised great power.

Today what was known to Central Asians as Altishahr is now a part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. With the creation and administration of the Chinese provincial system there has been extensive immigration of Han Chinese and sinicization of Xinjiang has taken place. Although the Turkic people still maintain a plurality in Xinjiang the population of Han Chinese is very likely to surpass all other ethnicities in the near future.[50]

معرض صور

See also

- Dzungar conquest of Altishahr

- East Turkestan independence movement

- History of the Uyghur people

- Xinjiang under Qing rule

الهامش

- ^ Biddulph (1880), p. 28.

- ^ Levi (2017), pp. 135–147.

- ^ Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period.

- ^ Woodman (1969), p. 90f.

- ^ Bellér-Hann (2008), p. 21f.

- ^ Dupuy (1993), pp. 769 and 869.

- ^ أ ب Levi (2017), p. 16.

- ^ Levi (2017), pp. 37–38.

- ^ أ ب Papas (2017).

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Millward (2007), pp. 108–109.

- ^ Millward (1998), p. 124.

- ^ Newby (2005), p. 39.

- ^ Wang (2017), p. 204.

- ^ Millward (1998), pp. 206–207.

- ^ Levi (2017), p. 136.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 24.

- ^ Levi (2017), p. 138.

- ^ Tyler (2003), p. 66.

- ^ Millward (1998), p. 171f.

- ^ Newby (2005), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Crossley (2006), p. 125.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 26.

- ^ Levi (2017), pp. 142–143.

- ^ Levi (2017), pp. 143–144.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 27.

- ^ Millward (1998), p. 224f.

- ^ Levi (2017), p. 144.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 28.

- ^ أ ب Levi (2017), p. 183.

- ^ Boulger (1893), p. 233.

- ^ Levi (2017), p. 184.

- ^ أ ب Kim (2004), p. 31.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Tyler (2003), p. 69.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 30.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Fairbank (1980), p. 127.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 7.

- ^ Fairbank (1980), p. 218.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 2–4.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. Map 1.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 181.

- ^ Levi (2017), pp. 197–199.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 48 and 83.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 86-87 and Map 2.

- ^ Kim (2004), pp. 88–89.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 176 and Map 2.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 185.

المراجع

- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- Biddulph, John (1880). Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh. Office of the superintendent of government printing.

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1893). A Short History of China: Being an Account for the General Reader of an Ancient Empire and People. W. H. Allen & Company Limited. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

seven khojas.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Siu, Helen F.; Sutton, Donald S. (1 January 2006). Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23015-6.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest; Dupuy, Trevor N. (1993). The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History: From 3500 B.C. to the Present (4th ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062700568.

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- Fairbank, John King; Liu, Kwang-Ching, eds. (1980). The Cambridge History of China. Volume 11, Part 2, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5212-2029-3.

- Kim, Hodong, ed. (2004). Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5.

- Levi, Scott C. (2017). The Rise and Fall of Khoqand, 1709-1876. University of Pittsburgh. ISBN 978-0-8229-6506-0.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2933-8.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231139243.

- Newby, L. J. (2005). The Empire And the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations With Khoqand C1760-1860. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-14550-8.

- Papas, Alexandre (November 20, 2017). "Khojas of Kashgar," Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.12. Retrieved 24 Apr 2019.

- Tyler, Christian (2003). Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3533-3.

- Wang, Ke (2017). "Between the "Ummah" and "China":The Qing Dynasty's Rule over Xinjiang Uyghur Society" (PDF). Journal of Intercultural Studies. Kobe University. 48.

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969). Himalayan Frontiers. Barrie & Rockcliff.

- Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle (1880). History of the Mongols (Part II: The Mongols proper and the Kalmuks). Longmans, Green, and Company.

- Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle (2008). History of the Mongols (Part II: The Mongols proper and the Kalmuks). New York: Cosimo.

- Liu, Tao Tao; Faure, David (1996). Unity and Diversity: Local Cultures and Identities in China. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-402-4.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .