رجينالد أوبري فسندن

رجينالد فسندن Reginald Fessenden | |

|---|---|

أبو البث الاذاعي | |

| وُلِدَ | 6 أكتوبر 1866 |

| توفي | 22 يوليو 1932 برمودا (مقبرة كنيسة سان مارك) |

| القومية | كندي |

| المهنة | مخترع |

| عـُرِف بـ | اختراع الابراق اللاسلكي |

رجينالد أوبري فسندن Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (6 أكتوبر 1866 - ت. 22 يوليو 1932)، هو مخترع كندي حاصل على الجنسية الأمريكية، قام بتجارب رائدة في الراديو، منها أول نقل اذاعي للصوت والموسيقي. فيما بعد حصل على المئات من براءات اختراع أجهزة في مجالات النقل عالي الطاقة، السونار والتلفزيون.

حياته المبكرة

وُلد رجينالد أوبري فسندن في 6 أكتوبر 1866، في إيست بولتون، كويبك، كندا، وكان أكبر الأبناء الأربعة لرڤرند جوسف إليشا فسندن وكلمنتينا ترنهولم فرسندن. كان جوسف فسندن راهباً في كنسة إنگلترة في كندا، وعلى مدار السنين انتقلت العائلة لعدد من الأماكن في مقاطعة أونتاريو. أثناء نشأته، كان رجينالد طالب مجتهد. عام 1877، في عمر الحادية عشر، التحق بمدرسة ترينتي كولدج في پورت هوپ، أونتاريو لمدة عامين. في سن الرابعة عشر، حصل فسندن على أستاذية الرياضيات من مدرسة بيشوپ كولدج في لنوكسڤيل، كويبك. في ذلك الوقت، كانت مدرسة بيشوپ كولدج، مدرسة فرعية لجامعة بيشوپ وتتشارك معها نفس الحرم الجامعي والمباني. في يونيو 1878، كانت المدرسة تضم 43 صبي فقط. ومن ثم، فعندما كان فسندن في سن المراهقة، كان يقوم بتدريس الرياضيات للأطفال الصغار في المدرسة وفي الوقت نفسه يدرس مع الطلبة الأكبر سناً في جامعة بيشوپ. كان عدد طلاب الجامعة عام 1883-84 25 طالب. في سن الثامنة عشر، ترك فسندن جامعة بيشوپ قبل التخرج، لكنه مع ذلك قام "إلى حد كبير باتمام جميع الأعمال الضرورية." (عدم الحصول على درجة علمية يمكن أن يكون قد قلل من فرص فسندن في الحصول على وظيفة؛ عندما تأسس قسم الهندسة الكهربية في جامعة مكگيل؛ رُفض طلب فسندن لشغل منصب رئيس الجامعة، وشغله أمريكي).

في السنتين التاليتين عمل مدرس، في معهد واتني في برمودا. وهناك ارتبط بهلن تروت. تزوجها في سبتمبر 1890، وأنجبا رجينالد كنلي فسندن.

عمله المبكر

Fessenden's classical education provided him with only a limited amount of scientific and technical training. Interested in increasing his skills in the electrical field, he moved to New York City in 1886, with hopes of gaining employment with the famous inventor, Thomas Edison. As recounted in his 1925 Radio News autobiography, his initial attempts were rebuffed; in his first application Fessenden wrote, "Do not know anything about electricity, but can learn pretty quick," to which Edison replied, "Have enough men now who do not know about electricity." However, Fessenden persevered, and before the end of the year was hired for a semi-skilled position as an assistant tester for the Edison Machine Works, which was laying underground electrical mains in New York City. He quickly proved his worth, and received a series of promotions, with increasing responsibility for the project. In late 1886, Fessenden began working directly for Thomas Edison at the inventor's new laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey. A broad range of projects included work in solving problems in chemistry, metallurgy, and electricity. However, in 1890, facing financial problems, Edison was forced to lay off most of the laboratory employees, including Fessenden.

Taking advantage of his recent practical experience, Fessenden was able to find positions with a series of manufacturing companies. Next, in 1892, he received an appointment as professor for the newly formed Electrical Engineering department at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana; while there he helped the Westinghouse Corporation install the lighting for the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Shortly thereafter in the same year, George Westinghouse personally recruited Fessenden for the newly created position of chair of the Electrical Engineering department at the Western University of Pennsylvania, renamed to the University of Pittsburgh in 1908. Fessenden began experimenting with wireless telephones in 1898; by 1899 he had a wireless communication system functioning between Pittsburgh and Allegheny City.[1]

عمله على الراديو

في أواخر تسعينيات القرن التاسع عشر، بدأ ظهور تقارير عن نجاح گوليلمو ماركوني المتنامي في عملية النقل بالراديو وجهاز الاستقبال. بدأ فسندن تجارب محدودة على الراديو، واستنتج في وقت قريب أنه يمكنه تطوير نظام أكثر كفاءة عن ناقل سپارك-گاپ ومستقبل-coherer التي دافع عنها أوليڤر لودجج وماركوني.

عقد مكتب الطقس وأول نقل اذاعي للصوت

In 1900 Fessenden left the University of Pittsburgh to work for the United States Weather Bureau, with the objective of proving the practicality of using a network of coastal radio stations to transmit weather information, thus avoiding the need to use the existing telegraph lines. The contract gave the Weather Bureau access to any devices Fessenden invented, but he would retain ownership of his inventions. Fessenden quickly made major advances, especially in receiver design, as he worked to develop audio reception of signals. His initial success came from a barretter detector, which was followed by the electrolytic detector that consisted of a fine wire dipped in nitric acid, and for the next few years this later device would set the standard for sensitivity in radio reception. As his work progressed, Fessenden also evolved the heterodyne principle, which combined two signals to produce a third audible tone. However, heterodyne reception was not fully practical for a decade after it was invented, since it required a means for producing a stable local signal, which awaited the development of the oscillating vacuum-tube.

The initial work took place at Rock Point, Maryland, located about 80 كيلومتر (50 mi) downstream from Washington, DC. While there, Fessenden, experimenting with a high-frequency spark transmitter, successfully transmitted speech on December 23, 1900 over a distance of about 1.6 kilometers (one mile), which appears to have been the first audio radio transmission. At this time the sound quality was too distorted to be commercially practical, but as a test this did show that with further technical refinements it would become possible to transmit audio using radio signals.

As the experimentation expanded, additional stations were built along the Atlantic Coast in both North Carolina and Virginia. However, in the midst of promising advances, Fessenden became embroiled in disputes with his sponsor. In particular, he charged that Bureau Chief Willis Moore had attempted to gain a half-share of the patents. Fessenden refused to sign over the rights, and his work for the Weather Bureau ended in August, 1902. This incident recalled F. O. J. Smith, a member of the House of Representatives from Maine, who had managed to gain a one-quarter interest in the Morse telegraph.

تأسيس نـِسكو

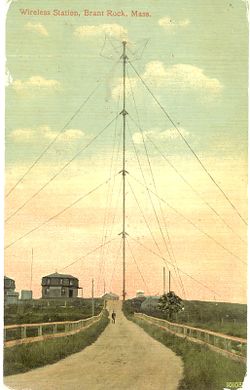

At that point, two wealthy Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania businessmen, Hay Walker, Jr., and Thomas H. Given, financed the formation of National Electric Signaling Company (NESCO) to carry on Fessenden's research. This included the development of both a high-power rotary-spark transmitter for long-distance radiotelegraph service, and a lower-powered continuous-wave alternator-transmitter, which could be used for both telegraphic and audio transmissions. Brant Rock, مساتشوستس became the center of operations for the new company.

Fessenden felt that, ultimately, a continuous-wave transmitter—one that produced a pure sine-wave signal on a single frequency—would be far more efficient, particularly because it could be used for quality audio transmissions. Fessenden contracted with General Electric to help design and produce a series of high-frequency alternator-transmitters.

ناقل روتاري-سپارك وأول نقل باتجاهين عبر الأطلسي

It was decided to try to establish a transatlantic radiotelegraph service, and, in January, 1906, employing his rotary-spark transmitters, Fessenden made the first successful two-way transatlantic transmission, exchanging Morse code messages between a station constructed at Brant Rock and an identical one built at Machrihanish, Scotland. (Marconi had only achieved one-way transmissions at this time.) However, the transmitters could not bridge this distance during daylight hours or in the summer, so work was suspended until later in the year. Then, on December 6, 1906, "owing to the carelessness of one of the contractors employed in shifting some of the supporting cables," the Machrihanish radio tower collapsed, abruptly ending the transatlantic work before it could ever go into commercial service.

الناقل-المُولد وأول بث إذاعي صوتي

The development of a rotary-spark transmitter was something of a stop-gap measure, to be used until a superior approach could be perfected. Fessenden felt that, ultimately, a continuous-wave transmitter—one that produced a pure sine wave signal on a single frequency—would be far more efficient, particularly because it could be used for quality audio transmissions. His design idea was to take a basic electrical alternator, which normally operated at speeds that produced alternating current of at most a few hundred hertz, and greatly speed it up in order to create electrical currents at tens of kilohertz. Thus, the high-speed alternator would produce a steady radio signal when connected to an aerial. Then, by simply placing a carbon microphone in the transmission line, the strength of the signal could be varied in order to add sounds to the transmission—in other words, amplitude modulation would be used to impress audio on the radio frequency carrier wave. However, it would take many years of expensive development before even a prototype alternator-transmitter would be ready, and a few more years beyond that for high-power versions to become available.

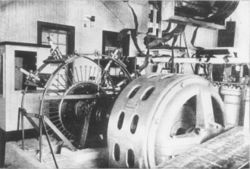

Fessenden contracted with General Electric to help design and produce a series of high-frequency alternator-transmitters. In 1903, Charles Proteus Steinmetz of GE delivered a 10 kHz version which proved of limited use and could not be directly used as a radio transmitter. Fessenden's request for a faster, more powerful unit was assigned to Ernst F. W. Alexanderson, and in August, 1906 he delivered an improved model which operated at a transmitting frequency of approximately 50 kHz, although with far less power than Fessenden's rotary-spark transmitters.

The alternator-transmitter achieved the goal of transmitting quality audio signals, but the lack of any way to amplify the signals meant they were somewhat weak. On December 21, 1906, Fessenden made an extensive demonstration of the new alternator-transmitter at Brant Rock, showing its utility for point-to-point wireless telephony, including interconnecting his stations to the wire telephone network. A detailed review of this demonstration appeared in The American Telephone Journal.[2]

A few days later, two additional demonstrations took place, which appear to be the first audio radio broadcasts of entertainment and music ever made to a general audience—maybe. (Beginning in 1904, the U.S. Navy had broadcast daily time signals and weather reports, but these employed spark transmitters, transmitting in Morse code). On the evening of December 24, 1906 (Christmas Eve), Fessenden used the alternator-transmitter to send out a short program from Brant Rock. It included a phonograph record of Ombra mai fu (Largo) by George Frideric Handel, followed by Fessenden himself playing the song O Holy Night on the violin. Finishing with reading a passage from the Bible: 'Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to men of good will' (Gospel of Luke 2:14).[3] He petitioned his listeners to write in about the quality of the broadcast as well as their location when they heard it. Surprisingly, his broadcast was heard several hundred miles away, however accompanying the broadcast was a disturbing noise. This noise was due to irregularities in the spark gap transmitter he used.[4]

On December 31, New Year's Eve, a second short program was broadcast. The main audience for both these transmissions was an unknown number of shipboard radio operators along the East Coast of the United States. Fessenden claimed that the Christmas Eve broadcast had been heard "as far down" as Norfolk, Virginia, while the New Year Eve's broadcast had reached places in the Caribbean. Although now seen as a landmark, these two broadcasts were barely noticed at the time and soon forgotten; the only first-hand account appears to be a letter Fessenden wrote on January 29, 1932 to his former associate, Samuel M. Kinter.[3] There are no known accounts in any ships' radio logs, nor any contemporary literature, of the reported holiday demonstrations.

(Broadcasting historian James E. O'Neal, in a series of articles on the Radio World website,[5][6] suggests that Fessenden, writing a quarter-century after the fact, may have confused the dates; O'Neal suggests Fessenden was remembering instead a series of tests he'd conducted in 1909.)

There is solid historical evidence, however, that Fessenden's demonstrations of "wireless telephony" were well known at the time. Documentation of Fessenden's demonstration of radio-transmitted voice is provided by a New York Times article, dated Sunday, September 1, 1907, titled: "Telephoning at Sea", which noted "The Hertzian waves will penetrate opaque substances, and the amplitude and intensity of the waves may be so varied as to reproduce faithfully the vibrations of the human voice." The same article further states that: "recently, the Fessenden wireless system demonstrated the practicability of transmitting spoken words from a tall mast at Brant Rock to Plymouth, twelve miles away."[7] Intense competition among developers of wireless technology, and the expectation of possible government contracts may have limited the scope of public promotion of the apparatus features and capabilities.

Fessenden's broadcast foreshadowed of the future of radio. (Although primarily designed for transmissions spanning a few kilometers, on a couple of occasions the test Brant Rock audio transmissions were apparently overheard by NESCO employee James C. Armor across the Atlantic at the Machrihanish site).

استمرار العمل واقالته من نـِسكو

The technical achievements made by Fessenden were not matched by financial success. Walker and Given had hoped to sell NESCO to a larger company such as the American Telephone & Telegraph Company, but were unable to find a buyer. Fessenden's formation of the Fessenden Wireless Company of Canada in Montreal in 1906 may have led to suspicion that he was trying to freeze Walker and Given out of a potentially lucrative competing transatlantic service. There were growing strains between Fessenden and the company owners, and finally Fessenden was dismissed from NESCO in January 1911. He in turn brought suit against NESCO for breach of contract. Fessenden won the initial court trial and was awarded damages, however, NESCO prevailed on appeal. To conserve assets, NESCO went into receivership in 1912, and Samuel Kintner was appointed general manager of the company. The legal stalemate would continue for over 15 years. In 1917, NESCO finally emerged from receivership, and was soon renamed the International Radio Telegraph Company. The company was sold to Westinghouse in 1920, and the next year its assets, including numerous important Fessenden patents, were sold to the Radio Corporation of America, which also inherited the Fessenden legal proceedings. Finally, on March 1, 1928, Fessenden settled his outstanding lawsuits with RCA, receiving a large cash payment.

تأثيره المستمر

After Fessenden left NESCO, Alexanderson continued to work on alternator-transmitter development at GE, mostly for long range radiotelegraph use. It took many years, but he eventually developed the high-powered Alexanderson alternator capable of transmitting across the Atlantic, and by 1916 the Fessenden-Alexanderson alternator was more reliable for transatlantic communication than spark apparatus. Also, after 1920, audio radio broadcasting became widespread, using vacuum-tube transmitters rather than the alternator, but employing the continuous-wave AM signals that Fessenden had helped introduce in 1906. In 1921, the Institute of Radio Engineers presented Fessenden with its IRE Medal of Honor,[8] and the next year the Board of Directors of City Trusts of Philadelphia awarded him a John Scott Medal and a cash prize of $800 for "his invention of a reception scheme for continuous wave telegraphy and telephony,"[9] and recognized him as "One whose labors had been of great benefit." Fessenden's first radio broadcast in 1906 is recognized as an IEEE Milestone.[10]

His legacy to radio includes three of his most notable achievements: the first audio transmission by radio (1900), the first two-way transatlantic radio transmission (1906), and the first radio broadcast of entertainment and music (1906).

السنوات الأخيرة

Although Fessenden ceased radio activities after his dismissal from NESCO in 1911, he continued to work in other fields. As early as 1904 he had helped engineer the Niagara Falls power plant for the newly formed Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. However, his most extensive work was in developing a type of sonar system, the so-called Fessenden oscillator, for submarines to signal each other, as well as a method for locating icebergs, to help avoid another disaster like the one that sank Titanic. At the outbreak of الحرب العالمية الأولى, Fessenden volunteered his services to the Canadian government and was sent to London, England where he developed a device to detect enemy artillery and another to locate enemy submarines.[11]

An inveterate tinkerer, Fessenden eventually became the holder of more than 500 patents. He could often be found in a river or lake, floating on his back, a cigar sticking out of his mouth and a hat pulled down over his eyes. At home he liked to lie on the carpet, a cat on his chest. In this state of relaxation, Fessenden could imagine, invent and think his way to new ideas, including a version of microfilm, that helped him to keep a compact record of his inventions, projects and patents. He patented the basic ideas leading to reflection seismology, a technique important for its use in exploring for petroleum. In 1915 he invented the fathometer, a sonar device used to determine the depth of water for a submerged object by means of sound waves, التي فاز من أجلها بالوسام الذهبي من ساينتفيك أمريكان عام 1929.[بحاجة لمصدر] حصل فسندن أيضاً على براءات اختراع [[ for tracer bullets, paging, television apparatus, turbo electric drive for ships, وغيرها.

وفاته

After settling his lawsuit with RCA, Fessenden purchased a small estate called "Wistowe" in Bermuda. He died there in 1932 and was interred in the cemetery of St. Mark's Church on the island. An editorial in the New York Herald Tribune said:

It sometimes happens, even in science, that one man can be right against the world. Professor Fessenden was that man. He fought bitterly and alone to prove his theories. It was he who insisted, against the stormy protests of every recognized authority, that what we now call radio was worked by continuous waves sent through the ether by the transmitting station as light waves are sent out by a flame. Marconi and others insisted that what was happening was a whiplash effect. The progress of radio was retarded a decade by this error. The whiplash theory passed gradually from the minds of men and was replaced by the continuous wave, with all too little credit to the man who had been right.

بيت رجينالد أوبري فسندن

منزل فسندن في 45 طريق وابان هيل بقرية چستنت هيل، نيوتون، مساتشوستس، وهو مدرج ضمن السجل الوطني للأماكن التاريخية والمعالم التاريخية الوطنية الأمريكية. اشترى فسندن المنزل عام 1906 أو قبل ذلك وامتلكه طوال حياته.[12]

مأثورات

"المخترع هو من يمكنه رؤية تطبيق الوسائل لتلبية الاحتياجات لخمسة أعوام قبل أن تتجلى للبارعين في الفنون."

— "اختراعات رجينالد أ. فسندن."[13]

انظر أيضاً

- براءات اختراع رجينالد فسندن

- مولد ألكسندرسون : استخدمه فسندن لأول بث اذاعي.

- سونار

منشورات

- R. A. Fessenden (1909). "Wireless Telephony," Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. New York: American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

المصادر

- المراجع

- ^ Kelly, Morgan (2010-06-21). "Genesis for Apple Inc. iPhone Was Pitt Experiments That Led to First Wireless Phone "Call" in 1900". Pitt Chronicle. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ Experiments and Results in Wireless Telephony The American Telephone Journal

- ^ أ ب Helen Fessenden, "Builder of Tomorrows" (1940), p. 153 - 154.

- ^ Belrose, John S (2002). "Reginald Aubery Fessenden and the Birth of Wireless Telephony" (PDF). Communications Research Centre Canada

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ O'Neal, James E. "Fessenden: World's First Broadcaster?--A Radio History Buff Finds That Evidence for the Famous Brant Rock Broadcast Is Lacking" Radio World Online. October 25, 2006

- ^ O'Neal, James E. "Fessenden — The Next Chapter" Radio World Online. December 23, 2008, retrieved June 29, 2009

- ^ Telephoning at Sea New York Times Archive.

- ^ "IEEE Medal of Honor Recipients" (PDF). IEEE. Retrieved 30 مارس 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "John Scott Medal Fund". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 55 (1422): p.344. 31 مارس 1922. doi:10.1126/science.55.1422.344-a. Retrieved 30 مارس 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Milestones:First Wireless Radio Broadcast by Reginald A. Fessenden, 1906". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ Seitz, Frederick (1999). The cosmic inventor: Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (1866-1932). Vol. 89. American Philosophical Society. pp. 41–46. ISBN 0-87169-896-X.

- ^ Fessenden, Reginald A. Inventing the Wireless Telephone and the Future

- ^ (يناير، 1925). Radio News, p. 1142.

- معلومات عامة

- Hugh G. J. Aitken, The Continuous Wave: Technology and American Radio, 1900-1932. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 1985.

- Brodsky, Ira. "The History of Wireless: How Creative Minds Produced Technology for the Masses" (Telescope Books, 2008)

- Susan J. Douglas, Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899-1922. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. 1987.

- Orrin E. Dunlap, Jr., Radio's 100 Men of Science, Reginald Aubrey Fessenden entry, p. 137-141. Harper & Brothers Publishers. New York. 1944.

- Helen M. Fessenden, Fessenden: Builder of Tomorrows. Coward-McCann, Inc. New York. 1940.

- Reginald A. Fessenden, "The Inventions of Reginald A. Fessenden." Radio News, 11 part series beginning with the January, 1925 issue.

- Reginald A. Fessenden, "Wireless Telephony," Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, XXXVII (1908): 553-629.

- Gary L. Frost, "Inventing Schemes and Strategies: The Making and Selling of the Fessenden Oscillator," Technology and Culture 42, no. 3 (July 2001): 462-488.

- S. M. Kinter, "Pittsburgh's Contributions to Radio," Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, (December, 1932): 1849-1862.

- David W. Kraeuter, "The U. S. Patents of Reginald A. Fessenden." Pittsburgh Antique Radio Society, Inc., Washington Pennsylvania. 1990. OCLC record 20785626.

- William M. McBride, "Strategic Determinism in Technology Selection: The Electric Battleship and U.S. Naval-Industrial Relations," Technology and Culture 33, no. 2 (April 1992): 248-277.

- Ormond Raby, Radio's First Voice, Macmillan Company of Canada Limited, 1970

براءات الاختراع

مقال رئيسي براءات اختراع رجينالد فسندن

وصلات خارجية

- "Fessenden: 100 Years of Radio".

- Belrose, John S. (September 5–7, 1995). "Fessenden and Marconi: Their Differing Technologies and Transatlantic Experiments During the First Decade of this Century". International Conference on 100 Years of Radio.

- Grant, John (January 26, 1907). "Experiments and Results in Wireless Telephony". The American Telephone Journal.

- Seitz, Frederick (1999). "The Cosmic Inventor". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.

- "George H. Clark Radioana Collection". National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. 1880–1950.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - "The National Electric Signaling Co". New England Wireless and Steam Museum.

- "Christmas Eve and the Birth of "Talk" Radio". All Things Considered. NPR. December 22, 2006.

- "Biography and photos". Telecommunications Hall of Fame.

"Fessenden, Reginald Aubrey". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Fessenden, Reginald Aubrey". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.- رجينالد أوبري فسندن at Find a Grave

- مقالات بأسلوب استشهاد غير متناسق

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: postscript

- CS1 errors: extra text: pages

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2008

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 maint: date format

- Persondata templates without short description parameter

- رواد الراديو

- مخترعون كنديون

- توماس إديسون

- حائزو الوسام الفخري لجمعية مهندسي الكهرباء والإلكترونيات

- طاقم تدريس جامعة پيتسبورگ

- مواليد 1866

- وفيات 1932

- أشخاص من شربروك

- أشخاص من أنگلوفون كويبك

- أشخاص تاريخيون وطنيون في كندا

- المدرجون في القاعة الوطنية لمشاهير المخترعين