پارميجانو رجانو

| Parmigiano Reggiano | |

|---|---|

| |

| بلد الأصل | Italy |

| المنطقة | Emilia-Romagna Lombardy |

| البلدة | Provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna (west of the Reno) and Mantua (on the right/south bank of the Po) |

| مصدر اللبن | Cows |

| مبستر | No |

| الملمس | Hard |

| زمن التعتيق | Minimum: 12 months Vecchio: 18–24 months Stravecchio: 24–36 months |

| الشهادة | Italy: DOP 1955 EU: PDO 1992 |

| |

Parmigiano Reggiano ( /ˌpɑrmɪˈdʒɑːnoʊ rɛˈdʒɑːnoʊ/, النطق بالإيطالية: [parmiˈdʒaːno redˈdʒaːno]) is an Italian hard, granular cheese produced from cow's milk and aged at least 12 months.

It is named after the producing areas, the provinces of Reggio Emilia, Parma, the part of Bologna west of the Reno, and Modena (all in Emilia-Romagna); and the part of Mantua (Lombardy) on the right/south bank of the Po. Parmigiano is the Italian adjective for Parma and Reggiano that for Reggio Emilia.

Both "Parmigiano Reggiano" and "Parmesan" are protected designations of origin (PDO) for cheeses produced in these provinces under Italian and European law.[1] Outside the EU, the name "Parmesan" can legally be used for similar cheeses, with only the full Italian name unambiguously referring to PDO Parmigiano Reggiano.

It has been called the "King of Cheeses"[2] and a "practically perfect food".[3]

الانتاج

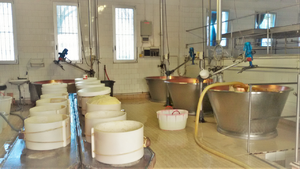

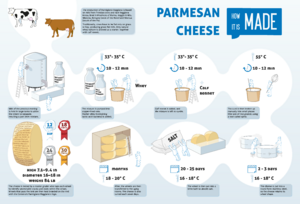

Parmigiano Reggiano is made from unpasteurised cow's milk. The whole milk of the morning milking is mixed with the naturally skimmed milk (which is made by keeping milk in large shallow tanks to allow the cream to separate) of the previous evening's milking, resulting in a part skim mixture. This mixture is pumped into copper-lined vats, which heat evenly and contribute copper ions to the mix.[4]

Starter whey (containing a mixture of certain thermophilic lactic acid bacteria) is added, and the temperature is raised to 33–35 °C (91–95 °F). Calf rennet is added, and the mixture is left to curdle for 10–12 minutes. The curd is then broken up mechanically into small pieces (around the size of rice grains). The temperature is then raised to 55 °C (131 °F) with careful control by the cheese-maker. The curd is left to settle for 45–60 minutes. The compacted curd is collected in a piece of muslin before being divided in two and placed in molds. There is 1,100 litres (290 US gal) of milk per vat, producing two cheeses each. The curd making up each wheel at this point weighs around 45 kilograms (99 lb). The remaining whey in the vat was traditionally used to feed the pigs from which Prosciutto di Parma (cured Parma ham) was produced. The barns for these animals were usually just a few metres away from the cheese production rooms.

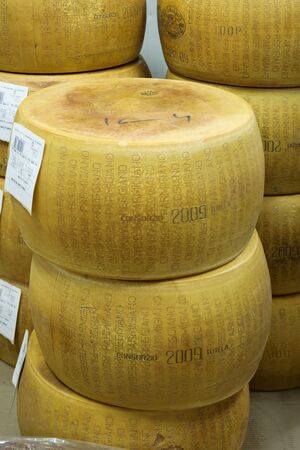

The cheese is put into a stainless steel, round form that is pulled tight with a spring-powered buckle so the cheese retains its wheel shape. After a day or two, the buckle is released and a plastic belt imprinted numerous times with the Parmigiano Reggiano name, the plant's number, and month and year of production is put around the cheese and the metal form is buckled tight again. The imprints take hold on the rind of the cheese in about a day and the wheel is then put into a brine bath to absorb salt for 20–25 days. After brining, the wheels are then transferred to the aging rooms in the plant for 12 months. Each cheese is placed on wooden shelves that can be 24 cheeses high by 90 cheeses long or 2160 total wheels per aisle. Each cheese and the shelf underneath it is then cleaned manually or robotically every seven days. The cheese is also turned at this time.

At 12 months, the Consorzio Parmigiano Reggiano inspects every wheel. The cheese is tested by a master grader who taps each wheel to identify undesirable cracks and voids within the wheel. Wheels that pass the test are then heat-branded on the rind with the Consorzio's logo. Those that do not pass the test used to have their rinds marked with lines or crosses all the way around to inform consumers that they are not getting top-quality Parmigiano Reggiano; more recent practices simply have these lesser rinds stripped of all markings.

Traditionally, cows are fed only on grass or hay, producing grass-fed milk. Only natural whey culture is allowed as a starter, together with calf rennet.[5]

The only additive allowed is salt, which the cheese absorbs while being submerged for 20 days in brine tanks saturated to near-total salinity with Mediterranean sea salt. The product is aged an average of two years.[6] The cheese is produced daily, and it can show a natural variability. True Parmigiano Reggiano cheese has a sharp, complex fruity/nutty taste with a strong savory flavour and a slightly gritty texture. Inferior versions can impart a bitter taste.

The average Parmigiano Reggiano wheel is about 18–24 cm (7–9 in) high, 40–45 cm (16–18 in) in diameter, and weighs 38 kg (84 lb).

Industry

All producers of Parmesan cheese belong to the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano (Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese Consortium), which was founded in 1928.[7] Besides setting and enforcing the standards for the PDO, the Consorzio also sponsors marketing activities.[8]

اعتبارا من 2017[تحديث], about 3.6 million wheels (approx. 137,000 metric tons) of Parmesan are produced every year; they use about 18% of all the milk produced in Italy.[9]

Most workers in the Italian dairy industry (bergamini) belong to the Italian General Confederation of Labour. As older dairy workers retire, younger Italians have tended to work in factories or offices. Immigrants have filled that role, with 60% of the workers in the Parmesan industry now immigrants from India, almost all Sikhs.[10]

Uses

Parmigiano Reggiano is commonly grated over pasta dishes, stirred into soups and risottos, and eaten on its own. It is often shaved or grated over other dishes like salads.[11]

Slivers and chunks of the hardest parts of the crust also called the rind are sometimes simmered in soups, broths, and sauces to add flavour. They can also be broiled and eaten as a snack if they have no wax on them. They can also be infused in olive oil or used in a steamer basket while steaming vegetables. [12]

History

According to legend, Parmigiano Reggiano was created in the course of the Middle Ages in Bibbiano, in the province of Reggio Emilia. Its production soon spread to the Parma and Modena areas. Historical documents show that in the 13th and 14th centuries, Parmigiano was already very similar to that produced today, which suggests its origins can be traced to far earlier. Some evidence suggests that the name was used for Parmesan cheese in Italy and France in the 17th-19th century.[6]

It was praised as early as 1348 in the writings of Boccaccio; in the Decameron, he invents a 'mountain, all of grated Parmesan cheese', on which 'dwell folk that do nought else but make macaroni and ravioli, and boil them in capon's broth, and then throw them down to be scrambled for; and hard by flows a rivulet of Vernaccia, the best that ever was drunk, and never a drop of water therein.'[13]

During the Great Fire of London of 1666, Samuel Pepys buried his "Parmazan cheese, as well as his wine and some other things" to preserve them.[14]

In the memoirs of Giacomo Casanova,[15] he remarked that the name "Parmesan" was a misnomer common throughout an "ungrateful" Europe in his time (mid-18th century), as the cheese was produced in the town of Lodi, Lombardy, not Parma. Though Casanova knew his table and claimed in his memoir to have been compiling a (never completed) dictionary of cheeses, his comment has been taken to refer mistakenly to a grana cheese similar to "Parmigiano", Grana Padano, which is produced in the Lodi area.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Parmigiano Reggiano has been the target of organized crime in Italy, particularly the Mafia or Camorra, which ambush delivery trucks on the Autostrada A1 in northern Italy between Milan and Bologna, hijacking shipments. The cheese is ultimately sold in southern Italy.[16] Between November 2013 and January 2015, an organised crime gang stole 2039 wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano from warehouses in northern and central Italy.[17]

October 27th is designated "Parmigiano Reggiano Day" by The Consortium of Parmigiano Reggiano. [18]

This day celebrating the "King of Cheese" originated in response to the 2 earthquakes hitting the area of origin in May 2012. The devastation was profound, displacing tens of thousands of residents, collapsing factories, and massively damaging historical churches, bell towers, and other landmarks.[19]

Years of cheese production were lost during the disaster, about $50 million worth, reported by the New York Times, potentially threatening the livelihood of cheesemakers whose families produced this product for generations. It was Modena native and renowned Chef Massimo Bottura, who The Consortium turned to for an outsized solution to help save the cheese. Bottura's three-Michelin starred Osteria Francescana, named the World's Top Restaurant in 2018 and 2016 by the prestigious San Pellegrino ranking (now in its Hall of Fame) is located in his hometown near the quake's epicenter. Massimo Bottura's response to the situation was a single recipe: Riso cacio e pepe. He invited the world through social media and online outlets to cook this new dish along with him launching "Parmigiano Reggiano Day" - October 27th.[20]

Aroma and chemical components

| القيمة الغذائية لكل 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| الطاقة | 392 kcal (1,640 kJ) |

3.22 g | |

| Sugars | 0.8 g |

| ألياف غذائية | 0.0 g |

25.83 g | |

| مشبع | 16.41 g |

| أحادي عدم التشبع | 7.52 g |

| متعدد عدم التشبع | 0.57 g |

35.75 g | |

| الڤيتامينات | |

| مكافئ ڤيتامين أ | (26%) 207 μg |

| ثيامين (B1) | (3%) 0.04 mg |

| ريبوفلاڤين (B2) | (28%) 0.33 mg |

| نياسين (B3) | (2%) 0.27 mg |

| ڤيتامين B6 | (7%) 0.09 mg |

| فولات (B9) | (2%) 7 μg |

| ڤيتامين ب12 | (50%) 1.2 μg |

| Vitamin C | (0%) 0.0 mg |

| ڤيتامين د | (3%) 19 IU |

| ڤيتامين E | (1%) 0.22 mg |

| ڤيتامين ك | (2%) 1.7 μg |

| آثار فلزات | |

| كالسيوم | (118%) 1184 mg |

| حديد | (6%) 0.82 mg |

| الماغنسيوم | (12%) 44 mg |

| فوسفور | (99%) 694 mg |

| پوتاسيوم | (2%) 92 mg |

| صوديوم | (107%) 1602 mg |

| زنك | (29%) 2.75 mg |

| مكونات أخرى | |

| ماء | 29.16 g |

| |

| Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Parmigiano has many aroma-active compounds, including various aldehydes and butyrates.[21] Butyric acid and isovaleric acid together are sometimes used to imitate the dominant aromas.[22]

Parmigiano is also particularly high in glutamate, containing as much as 1.2 g of glutamate per 100 g of cheese. The high concentration of glutamate explains the strong umami taste of Parmigiano.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Parmigiano cheese typically contains cheese crystals, semi-solid to gritty crystalline spots that at least partially consist of the amino acid tyrosine.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Name uses

The name is legally protected and, in Italy, exclusive control is exercised over the cheese's production and sale by the Parmigiano Reggiano cheese Consorzio, which was created by a governmental decree. Each wheel must meet strict criteria early in the aging process, when the cheese is still soft and creamy, to merit the official seal and be placed in storage for aging. Because it is widely imitated, Parmigiano Reggiano has become an increasingly regulated product, and in 1955 it became what is known as a certified name (which is not the same as a brand name). In 2008, an EU court determined that the name "Parmesan" in Europe only refers to Parmigiano Reggiano and cannot be used for imitation Parmesan.[23][24][25] Thus, in the European Union, "Parmigiano Reggiano" is a protected designation of origin (PDO – DOP in Italian); legally, the name refers exclusively to the Parmigiano Reggiano PDO cheese manufactured in a limited area in northern Italy. Special seals identify the product as authentic, with the identification number of the dairy, the production month and year, a code identifying the individual wheel and stamps regarding the length of aging.[26]

Generic "Parmesan" cheese

Generic Parmesan cheese is a family of hard grating cheeses made from cow's milk and inspired by the original Italian cheese.[27] They are generally pale yellow in color, and usually used grated on dishes like spaghetti, Caesar salad, and pizza.[28] American generic Parmesan is frequently sold already grated and has been aged for less than 12 months.[2] The marketing phenomenon of imitation of Italian agri-food products is known by the name of Italian Sounding.[29]

Within the European Union, the term Parmesan may only be used, by law, to refer to Parmigiano Reggiano itself, which must be made in a restricted geographic area, using stringently defined methods. In many areas outside Europe, the name "Parmesan" has become genericised, and may denote any of a number of hard Italian-style grating cheeses,[30][31] often commercialised under names intended to evoke the original, such as Parmesan, Parmigiana, Parmesana, Parmabon, Real Parma, Parmezan, or Parmezano.[2] After the European ruling that "parmesan" could not be used as a generic name, Kraft renamed its grated cheese "Pamesello" in Europe.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Production

Generic Parmesans may be legally defined in various jurisdictions.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the United States, the Code of Federal Regulations includes a Standard of Identity for "Parmesan and reggiano cheese".[32] This defines both aspects of the production process and of the final result. In particular, parmesan must be made of cow's milk, cured for 10 months or more, contain no more than 32% water, and have no less than 32% milkfat in its solids.[32] Most grated parmesans in the US have cellulose added as an anti-caking agent, with up to 4% considered acceptable under Federal law.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Kraft Foods is a major North American producer of generic Parmesan and has been selling it since 1945.[33][34] As parmesan is a common seasoning for pizzas and pastas, many major pizza and pasta chains offer it.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Several manufacturers have been investigated for allegedly going beyond the 4% cellulose limit.[35] In one case, FDA findings found "no parmesan cheese was used to manufacture" a Pennsylvania manufacturer's grated cheese labeled "Parmesan", apparently made from a mixture of other cheeses and cellulose. The manufacturer declared bankruptcy in 2014 and their president was expected to plead guilty to criminal charges, facing up to $100,000 in fines and a year in jail.[35]

Similar cheeses

Grana Padano

Grana Padano is an Italian cheese similar to Parmigiano Reggiano, but is produced mainly in Lombardy, where "Padano" refers to the Po Valley (Pianura Padana); the cows producing the milk may be fed silage as well as grass; the milk may contain slightly less fat, milk from several different days may be used, and must be aged a minimum of 9 months.

Gran Moravia

Gran Moravia is a cheese from the Czech Republic similar to Grana Padano and Parmigiano.[36]

Reggianito

Reggianito is an Argentine cheese similar to Parmigiano. Developed by Italian Argentine cheesemakers, the cheese is made in smaller wheels and aged for less time, but is otherwise broadly similar.

See also

References

- ^ Case C-132/05 Commission v Germany European Commission Legal Service, July 2008 Archived 2019-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت Olmsted, Larry (November 19, 2012). "Most Parmesan Cheeses In America Are Fake, Here's Why". Forbes (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-03-23.

... that it has earned the nickname in the dairy industry, 'The King of Cheeses'.

- ^ Ruggeri, Amanda (2019-01-28). "Italy's practically perfect food". Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- ^ Molly McDonough, "Why Copper Vats Matter", Culture: The Word on Cheese July 19, 2017

- ^ "Standard di Produzione Archived 2006-05-13 at the Wayback Machine". Disciplinare del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano D.O.P. (fourth paragraph). Famiglia Gastaldello, 2005–2008.

- ^ أ ب "Learn the Difference Between Parmesan and Parmigiano Reggiano". The Spruce Eats (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano, "The Consortium and its History" [1]

- ^ Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano, "2018 Export Projects"

- ^ CLAL (Italian dairy consulting company), "Italy: Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese Production" [2]

- ^ Mitzman, Dany (25 June 2015). "The Sikhs who saved Parmesan". BBC News. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ "Discover Parmigiano Reggiano DOP". Eataly (in الإنجليزية). 2021-01-02. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ "7 Genius Uses For Parmesan Rinds". HuffPost (in الإنجليزية). 2016-07-14. Retrieved 2021-12-30.

- ^ Giovanni Boccaccio, Decamerone VIII 3. The translation quoted here is that by J.M. Rigg Archived 2008-10-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ See Pepys's diary entry for 4 September, 1666

- ^ Casanova, Histoire de ma vie 8:ix.

- ^ McMahon, Barbara (3 December 2006). "It's hard cheese for Parmesan producers targeted by Mafia". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Maxi-furto di Parmigiano Reggiano: rubate 2mila forme, 11 arresti" [Parmigiano Reggiano heist: 2000 wheels stolen, 11 arrested] (in الإيطالية). 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "The Touching Story Behind Parmigiano Reggiano Day". La Cucina Italiana (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ^ "The Touching Story Behind Parmigiano Reggiano Day". La Cucina Italiana (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ "The Touching Story Behind Parmigiano Reggiano Day". La Cucina Italiana (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ Qian, Michael; Reineccius, Gary. "Potent Aroma Compounds in Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese Studied Using a Dynamic Headspace (purge-trap) Method". Flavour and Fragrance Journal, Volume 18 Issue 3, 7 April 2003 (pp. 252–259).

- ^ "I Know What I Like: Understanding Odor Preferences". The Fragrance Foundation, 2008.

- ^ Marsha A. Echols Geographical Indications for Food Products – 2008 Page 190 – "A defence was that the name 'Parmesan' has become generic and so cannot be a protected designation of origin. The Court disagreed. It commented that 'in the present case it is far from clear that the designation parmesan has become ..."

- ^ Bernard O'Connor – The Law of Geographical Indications – Page 136 2004 – "... name "Parmesan" may not become generic. See on http://europe/eu/int[dead link], "Case Law". 44 Where a registered name contains within it the name of an agricultural product or foodstuff that is considered generic, the use of that generic name on ...

- ^ The Great Food Robbery: How Corporations Control Food 2012 "In 2008, however, the EU ruled that the same applied to all cheese produced under the name "Parmesan", a generic term widely used for cheeses produced around the world. The EU issued a similar ruling for Feta, claiming that it could be ...

- ^ Zeldes, Leah A. (2010-10-06). "Eat this! Parmigiano-Reggiano, the king of cheeses". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)[dead link] - ^ Preedy, Victor R.; Watson, Ronald Ross; Patel, Vinood B., eds. (2013-10-15). Handbook of cheese in health: Production, nutrition and medical sciences. Human Health Handbooks. Vol. 6. The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers. p. 264. doi:10.3920/978-90-8686-766-0. ISBN 978-90-8686-211-5. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ Hintz, Martin; Percy, Pam (2008-02-26). Wisconsin Cheese: A Cookbook and Guide to the Cheeses of Wisconsin – Martin Hintz, Pam Percy – Google Books. ISBN 9780762751969. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ "In cosa consiste l'Italian Sounding" (in الإيطالية). Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Oxford Companion to Food, s.v. 'parmesan'

- ^ Cox, James (9 September 2003). "What's in a name?". USA Today. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ أ ب Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services (April 1, 2006), "§ 133.165: Parmesan and reggiano cheese", Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 21 – Food and Drugs, Chapter I – Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services (continued) (Parts 1–1299), Part 133 – Cheeses and related cheese products, United States Government Publishing Office, pp. 338–339

- ^ Justin M. Waggoner (12 October 2007). "Acquiring a European Taste for Geographical Indications" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ^ Brodsy, Alyson. "U.S. cheese maker says it can produce Parmesan faster | Business | Indiana Daily Student". Idsnews.com. Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ أ ب Lydia Mulvany. The Parmesan Cheese You Sprinkle on Your Penne Could Be Wood: Some Brands Promising 100 Percent Purity Contained No Parmesan at All. Bloomberg Business. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Smetana, Jiří (15 February 2010). "Italové kupují český "parmazán" z Litovle" (in التشيكية). iDnes. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

External links

- Official website

- U.S. website

Media related to Parmigiano-Reggiano at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Parmigiano-Reggiano at Wikimedia Commons

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- CS1 الإيطالية-language sources (it)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with dead external links from April 2020

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Articles with dead external links from November 2021

- CS1 التشيكية-language sources (cs)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles with hRecipes

- Articles with Adr microformats

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2017

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Pages with empty portal template

- Italian cheeses

- Italian products with protected designation of origin

- Cow's-milk cheeses

- Umami enhancers

- Cheeses with designation of origin protected in the European Union

- Cuisine of Emilia-Romagna

- مقالات تحتوي مقاطع ڤيديو