پووتسك

پووتسك

Płock | |

|---|---|

| Stołeczne Książęce Miasto Płock Princely Capital City of Płock | |

| |

| الشعار: Virtute et labore augere | |

| الإحداثيات: 52°33′N 19°42′E / 52.550°N 19.700°E | |

| البلد | |

| الڤويڤودية | |

| المقاطعة | مقاطعة مدينة |

| تأسست | القرن العاشر |

| حقوق البلدة | 1237 |

| الحكومة | |

| • الرئيس | Andrzej Nowakowski |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 88٫06 كم² (34�00 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 60 m (200 ft) |

| التعداد (31 December 2020) | |

| • الإجمالي | 118٬268 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 09-400 to 09-411, 09-419 to 09-421 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +48 024 |

| Car plates | WP |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | Płock City Hall |

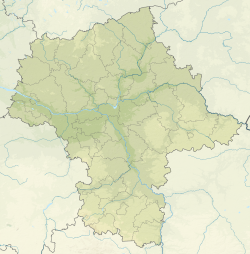

پووتسك ( Płock ؛ تُنطق [pwɔt͡sk] (![]() استمع)) هي مدينة في وسط پولندا، على نهر ڤيستولا. It is in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been the capital of the Płock Voivodeship (1975–1998). According to the data provided by GUS on 31 December 2020 there were 118,268 inhabitants in the city.[1] Its full ceremonial name, according to the preamble to the City Statute, is Stołeczne Książęce Miasto Płock (the Princely or Ducal Capital City of Płock). It is used in ceremonial documents as well as for preserving an old tradition.[2]

استمع)) هي مدينة في وسط پولندا، على نهر ڤيستولا. It is in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been the capital of the Płock Voivodeship (1975–1998). According to the data provided by GUS on 31 December 2020 there were 118,268 inhabitants in the city.[1] Its full ceremonial name, according to the preamble to the City Statute, is Stołeczne Książęce Miasto Płock (the Princely or Ducal Capital City of Płock). It is used in ceremonial documents as well as for preserving an old tradition.[2]

Płock is a capital of the powiat (county) in the west of the Masovian Voivodeship. From 1079 to 1138 it was the capital of Poland. The Wzgórze Tumskie ("Cathedral Hill") with the Płock Castle and the Catholic Cathedral, which contains the sarcophagi of a number of Polish monarchs, is listed as a Historic Monument of Poland.[3] It was the main city and administrative center of Mazovia in the Middle Ages before the rise of Warsaw as a major city of Poland, and later it remained a royal city of Poland.[4] It is the cultural, academic, scientific, administrative and transportation center of the west and north Masovian region.[5] Płock is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Płock, one of the oldest dioceses in Poland, founded in the 11th century, and it is also the worldwide headquarters of the Mariavite Church. In Płock are located also the Marshal Stanisław Małachowski High School, the oldest school in Poland and one of the oldest in Central Europe, and the Płock refinery, the country's largest oil refinery.

التاريخ

العصور الوسطى

The area was long inhabited by pagan peoples. In the 10th century, a fortified location was established high of the Vistula River's bank. This location was at a junction of shipping and routes and was strategic for centuries. Its location was a great asset. In 1009 a Benedictine monastery was established here. It became a center of science and art for the area.

During the rule of the first monarchs of the Piast dynasty, even prior to the Baptism of Poland, Płock served as one of the monarchial seats, including that of Prince Mieszko I and King Bolesław I the Brave. The king built the original fortifications on Cathedral Hill (پولندية: Wzgórze Tumskie), overlooking the Vistula River. From 1037 to 1047, Płock was capital of the independent Mazovian state of Miecław. Płock has been the residence of many Mazovian princes. In 1075, a diocese seat was created here for the Roman Catholic church.[6] From 1079 to 1138, during the reign of the Polish monarchs Władysław I Herman and Bolesław III Wrymouth, the city was the capital of Poland, then earning its title as the Ducal Capital City of Płock (پولندية: Stołeczne Książęce Miasto Płock).[7] As a result of the fragmentation of Poland into smaller duchies, from 1138 it was the capital of the Duchy of Masovia, and afterwards the Duchy of Płock.[6] In 1180 the present-day Marshal Stanisław Małachowski High School (Małachowianka), the oldest still existing school in Poland and one of the oldest in Central Europe, was established.[8] Among its notable graduates is scholar and jurist Paweł Włodkowic, a precursor of religious freedom in Europe, who studied there in the late 14th century.[9]

In 1237 Płock was officially granted town rights, renewed in 1255.[6] In the 14th century King Casimir III the Great vested Płock with vast privileges.[6] The first Jewish settlers came to the city in the 14th century, responding to the extension of rights by the Polish kings. In 1495 the Duchy of Płock was integrated directly with the Polish Crown as a reverted fief.

العصر الحديث

In the early modern period, Płock was a royal city of Poland[4] and capital of the Płock Voivodeship[8] within the larger Greater Poland Province of the Polish Crown. The 16th century was the golden age of the city,[8] before it suffered major losses in population due to plague, fire, and warfare, with wars between Sweden and Poland in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. At that time, the Swedes destroyed much of the city, but the people rebuilt and recovered.[5] In the late 18th century, it took down the old city walls, and made a New Town, filled with many German migrants.[5]

In the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 the city was annexed by Prussia.[8] From 1807 it was part of the short-lived Polish Duchy of Warsaw and in 1815 it became part of Congress Poland,[8] later on fully annexed by the Russian Empire. In 1831, the last sejm of Congress Poland was held in the Płock town hall.[8] It was a seat of provincial government and an active center; its economy was closely tied to major grain trade. It laid out a new city plan in the early 19th century, as new residents continued to arrive. Many of its finest buildings were constructed in this period in the Neoclassical style. In 1820 the Płock Scientific Society was founded,[6] and in the late 19th century the city began to industrialize.[5] In 1863 local Poles fought in the January Uprising against Russia.[6] The leader of the uprising in the Płock region, Zygmunt Padlewski, was executed by the Russians in Płock in May 1863.[8] In 1905, large demonstrations of Polish youth and workers took place in Płock.[6]

During World War I, Płock was occupied by Germany from 1915 to 1918,[8] and in 1918 Poland regained independence, and Płock was immediately reintegrated with Poland. In August 1920, the city became famous for its successful heroic defense against the Soviets during the Polish–Soviet War.[6][8][10] 250 Polish defenders, including 100 civilians, were killed in the battle.[10] In 1921, Marshal Józef Piłsudski visited Płock and awarded the city with the Cross of Valour, making Płock the second Polish city to be awarded with a Polish military decoration (shortly after Lwów).[10]

الحرب العالمية الثانية

Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the city of Płock was annexed into the Reich as part of the Regierungsbezirk Zichenau. The Germans renamed the city Schröttersburg in 1941 after the former Prussian Baron of the Empire Friedrich Leopold von Schrötter.[11]

As part of the Intelligenzaktion, the Germans carried out mass arrests of Poles, who were then imprisoned in the local prison, and around 200 of whom were murdered in large massacres in Łąck between October 1939 and February 1940.[12] Among the victims were Polish teachers, activists, shopowners, notaries, local officials, pharmacists, directors and members of the Polish Military Organisation.[13] Next mass arrests of about 2,000 Poles from Płock and the Płock County were carried out in April 1940, and in June 1940, another 200 Poles from various settlements in the region were imprisoned in the local prison.[14] Some prisoners were then deported and murdered in the Soldau concentration camp.[15] Some teachers from Płock were also among Polish teachers murdered in the Mauthausen concentration camp.[16] In 1940, Germans murdered 80 elderly and disabled people from Płock in the nearby village of Brwilno.[17] The Archbishop of Płock Antoni Julian Nowowiejski and the auxiliary Bishop Leon Wetmański were imprisoned in the nearby village of Słupno, and then in 1941 also murdered in the Soldau concentration camp, where also many other local priests were killed.[18] Nowowiejski and Wetmański are now considered two of the 108 Blessed Polish Martyrs of World War II by the Catholic Church. Poles were also subjected to expulsions, 1,300 Poles were expelled in November and December 1939, and over 4,000 also in February and March 1941.[19] Nazi Germany also deported people as forced laborers for German factories, treating them harshly. The Germans also established and operated two forced labour subcamps of the local prison,[20][21] and an additional forced labour "education" camp in the city.[22] In the winter of 1942–1943, a freight train with kidnapped Polish children arrived to the Płock-Radziwie station, and around 300 of the children froze to death and were buried by the Germans in the forests of nearby Łąck.[23] Since 1943, the local Sicherheitspolizei carried out deportations of Poles including teenage boys to the Stutthof concentration camp.[24]

At the same time, the Nazis were also brutalizing the Jewish population of Płock. They conscripted them for forced labor and established a Jewish ghetto in Płock in 1940. In that ghetto, up to ten people shared each room. Medical supplies were inadequate and diseases spread. Germans murdered many Jews in Płock but most were deported to other areas and then on to be murdered in Treblinka. By the war's end, only 300 Jewish residents were known to have survived, of more than 10,000 in the region (for more information see Jewish history below). Some Poles in Płock tried to assist their Jewish neighbors by smuggling food to them and sneaking food to them when they were rounded up and had to stand in the street for an entire day on a bitterly cold day waiting to be deported.[25]

Germans closed Polish institutions and the Polish press, and looted or destroyed numerous Polish cultural monuments, collections and archives, including the rich collection of the Płock Scientific Society.[26][27] The collections of local museums, the cathedral's ancient treasury, church archives and the diocesan library were stolen and taken to museums in Königsberg, Wrocław and Berlin.[27] The local seminary was converted by the Germans into barracks of the SS.[26]

Despite such circumstances, the city remained the center of the Polish underground resistance movement.[6] In September 1942, the Germans publicly hanged 13 Polish resistance members in the Old Town.[28] In January 1945, the retreating Germans burned 79 Poles alive.[8] The city was restored to Poland, although with a Soviet-installed communist regime, which remained in power until the Fall of Communism in the 1980s.

التاريخ الحديث

في 1976, Płock was one of the centers of large anti-communist protests.

المناخ

Płock has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb) using the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm or a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb) using the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm.[29][30]

| Climate data for پووتسك (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.1 (89.8) |

34.3 (93.7) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.3 (99.1) |

35.5 (95.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

37.3 (99.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.6 (−32.1) |

−27.7 (−17.9) |

−23.7 (−10.7) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−23.9 (−11.0) |

−35.6 (−32.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30.4 (1.20) |

26.2 (1.03) |

30.6 (1.20) |

31.6 (1.24) |

50.8 (2.00) |

48.2 (1.90) |

40.5 (1.59) |

42.9 (1.69) |

47.3 (1.86) |

35.0 (1.38) |

33.7 (1.33) |

33.4 (1.31) |

450.7 (17.74) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 6.3 (2.5) |

5.9 (2.3) |

3.9 (1.5) |

1.0 (0.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.1) |

1.7 (0.7) |

3.7 (1.5) |

6.3 (2.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.62 | 13.77 | 13.20 | 11.40 | 12.37 | 12.40 | 13.13 | 12.30 | 11.50 | 12.80 | 14.60 | 15.90 | 158.99 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0 cm) | 15.3 | 14.1 | 6.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 11.8 | 52.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.7 | 83.5 | 77.4 | 69.2 | 70.0 | 71.7 | 72.0 | 70.9 | 77.6 | 83.1 | 88.5 | 88.4 | 78.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 48.9 | 68.8 | 132.3 | 203.8 | 254.8 | 256.9 | 257.9 | 247.0 | 166.5 | 111.2 | 47.3 | 36.4 | 1٬831٫7 |

| Source 1: Institute of Meteorology and Water Management[31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteomodel.pl (records, relative humidity 1991–2020)[39][40][41] | |||||||||||||

الثقافة والدين

The Museum of Mazovia provides exhibits and interpretation of the city and region's history. Płock is the oldest legislated seat of the Roman Catholic diocese; the Masovian Blessed Virgin Mary Cathedral was built here in the first half of the 12th century and houses the sarcophagi of Polish monarchs. It is one of the five oldest cathedrals in Poland.

الرحمة المقدسة

The city is famous for the Divine Mercy Sanctuary, where the apparition of Jesus to Saint Faustina Kowalska took place, and the Divine Mercy devotion was revealed.[42]

الكنيسة المارياڤية

From the visions of Feliksa Kozłowska in 1893, the Mariavite order of priests originated, originally working to renew clergy within the Roman Catholic Church. Despite repeated attempts, they were not recognized by the Vatican and in the early 20th century established a separate and independent denomination. This site is the main seat of the Mariavite bishops. Their most important church was built here in the beginning of the 20th century; it is called the Temple of Mercy and Charity and is situated in a pleasant garden on the hill on which the historical centre of Płock is built, near the Vistula River. Poland in total has about 25,000 members of the Old Catholic Mariavite Church, as it is now named, with another 5,000 in France. A smaller breakaway church, the Catholic Mariavite Church, which has an integrated female priesthood (since 1929), has 3,000 members in Poland.

التاريخ اليهودي

The Jewish presence in Płock (Yiddish: Plotzk) dates back many centuries, probably to the 13th and 14th centuries, when records include them. The Polish kings extended rights to them in 1264 and the 14th century, and provided continued political support through the centuries.[43] At the beginning of the 19th century, their more than 1,200 residents comprised more than 48% of the city's population in what is considered the city's Old Town; through the century, their proportions ranged from 30 and 40 percent.[44] It varied as German migrants were arriving in the region, and the area was becoming urbanized, as more people moved to the city. After Płock fell to Russia in the 19th century, it was part of the Pale of Settlement, where Russians allowed the settlement of Jews. As in other parts of the Russian Partition of Poland, they were restricted to employment in trades and crafts.[43]

In the late 19th century, Jews established two factories to produce farm machines and tools, and the first iron foundry in the city. They had two synagogues and two cemeteries (dating to the 15th century), religious and secular schools, and established a library and hospital. They contributed strongly to the economy and culture of the city. In the early 20th century, they had two newspapers, representing active political parties.[43]

In 1939, Płock had a Jewish population of 9,000, an estimated 26% of the city's total.[44] After the 1939 invasion of Poland, German Nazi persecution began, about 2,000 Jews fled the city, with half going to Soviet-controlled territory. They were assigned to locations far from the front. In 1940, the Nazis established a ghetto in Płock. They started actions against the Jews, killing those in an old people's home and sick children, and transporting others to be killed at Brwilski Forest. Ultimately, they transported the Jews to 20 camps and sites in the Radom district, where in 1942 those still alive were sent to Treblinka to be murdered.[43] There is evidence that a few Poles tried to help their Jewish neighbors in Plock by smuggling food into the ghetto, sneaking food to them while they were awaiting deportation, and throwing loaves of bread to them on the transport trucks. While small acts, they took courage.[45] By 1946, only 300 Jews survived in Płock. While they were active in the new politics, gradually the Jews left, and by 1959 three remained.[44] Herman Kruk, a survivor and notable chronicler of life inside the Nazi concentration camps, was born in Płock in 1897.[46]

The small synagogue, built in 1810, was one of the few to survive World War II in the Masovia region of Poland. The Great Synagogue was destroyed during the Holocaust. The small synagogue was designated as a historic building about 1960, but deteriorated in physical condition while vacant. It was renovated and adapted for use as a museum, opening in April 2013 as the Museum of Masovian Jews, a branch of the Museum of Płock Mazowiecki.[47]

في الثقافة الشعبية

Various Polish films were shot in Płock, including Satan from the Seventh Grade, The Scar, The Doubles, Loving, as well as the 1960s TV series Stawka większa niż życie.[48]

المطبخ

The officially protected traditional foods originating from Płock (as designated by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland) include kiełbasa tumska, a local type of kiełbasa named after Wzgórze Tumskie (Cathedral Hill),[49] and baleron płocki, a local type of baleron, a popular Polish smoked lunch meat.[50]

الاقتصاد

الصناعة الرئيسية بالمدينة هي تكرير النفط، التي تأسست في 1960. أكبر مصفاة نفط في پولندا (مصفاة پووتسك ) والشركة المالكة لها PKN Orlen، كلاهما يوجدا بالمدينة. ويغذيها خط أنابيب دروژبا الضخم من روسيا متجهاً إلى ألمانيا. الأنشطة الصناعية المصاحبة للمصفاة هي الخدمات الفنية والإنشاءات. ويوجد مصنع لڤاي ستراوس في پووتسك.

التعليم

- Szkoła Wyższa im. Pawła Włodkowica

- Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa w Płocku

- Płock Campus of Warsaw University of Technology

- LO im. Marszałka Stanisława Małachowskiego w Płocku - the oldest school in Poland, dating back to 1180[8]

- LO im. Wladysława Jagiełły w Płocku

- III LO im. Marii Dąbrowskiej w Płocku

- IV LO im. Bolesława Krzywoustego w Płocku

النقل

النقل الجماعي

- KM Płock - Komunikacja Miejska Płock[51]

Bus service covers the entire city, with 41 routes.

- PKS Płock - Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacji Samochodowej w Płocku S.A.[52]

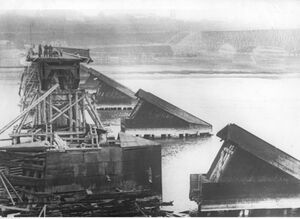

الجسور

الرياضة

- Wisła Płock – one of Poland's most successful handball teams, playing in the Superliga, Poland's top division, multiple Polish Champion and multiple Polish Cup winner

- Wisła Płock – football team, currently playing in the Ekstraklasa, Poland's top division, Polish Cup and Polish SuperCup winner in 2006

السياسة

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Płock constituency

- Julia Pitera, PO

- Mirosław Koźlakiewicz, PO

- Andrzej Nowakowski, PO

- Wojciech Jasiński, Pis

- Marek Opioła, Pis

- Robert Kołakowski, Pis

- Dariusz Kaczanowski, Pis

- Waldemar Pawlak, PSL

- Adam Struzik, PSL

- Jolanta Szymanek-Deresz, SLD+SDPL+PD+UP (died in a plane crash 10 April 2010)

أشخاص بارزون

- Bolesław III Wrymouth (1086–1138), Duke of Poland

- Józef Pius Dziekoński (1844–1924), architect and heritage conservator

- Kazimierz Zalewski (1849–1919), dramatist, literary and theatre critic

- Ludwik Krzywicki (1859–1941), Marxist anthropologist, economist and sociologist

- Edward Flatau (1868–1932), neurologist and psychiatrist

- Władysław Broniewski (1897–1962), poet, writer, translator and soldier

- Stefan Themerson (1910–1988), writer of children's literature, poet and novelist

- Rozka Korczak (1921–1988), partisan leader during World War II

- Włodzimierz Brus (1921–2007), economist and politician

- Antoni Gawryłkiewicz (1922-2007), Holocaust resister and a Righteous among the Nations

- Anna Kochanowska (1922–2019), radio journalist, literary director and politician

- Ryszard Syski (1924–2007), Polish-American mathematician

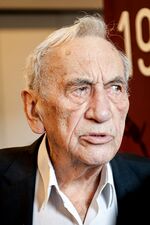

- تاديوش مازوڤيتسكي (1927–2013), author, journalist, philanthropist and Christian-democratic politician, formerly one of the leaders of the Solidarity movement, and the first non-communist Polish prime minister since 1946

- Wojciech Jankowski (born 1963), rower and Olympic medallist

- Michał Łogosz (born 1977), badminton player

- Szymon Marciniak (born 1981), football referee

- Piotr Więcek (born 1990), drifting driver

- Kamil Syprzak (born 1991), handball player

- Paweł Halaba (born 1995), volleyball player

- Bartosz Kwolek (born 1997), volleyball player, 2018 World Champion

- Marcin Bułka (born 1999), goalkeeper

بلدات توأم - مدن شقيقة

بلدات توأم سابقة:

Navapolatsk، بلاروس (منذ 1996 وحتى 2022)

Navapolatsk، بلاروس (منذ 1996 وحتى 2022) Mytishchi في روسيا (منذ 2006 وحتى 2022)

Mytishchi في روسيا (منذ 2006 وحتى 2022)

In March 2022, Płock suspended its partnership with the Russian city of Mytishchi and the Belarussian city of Navapolatsk as a response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[56]

معرض صور

Panorama of Płock from the Vistula

The Gothic façade of the Płock Cathedral

St. Bartholomew's Church

Temple of Mercy and Charity, the main seat of the Mariavite Church

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ أ ب "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 16 October 2021. Data for territorial unit 1462000.

- ^ (in پولندية)(Statut Miasta Płocka) Załącznik do Uchwały Nr 302/XXI/08 Rady Miasta Płocka z dnia 26 lutego 2008 roku (Dz. Urz. Woj. Mazowieckiego z 2008 r. Nr 91, poz. 3271 Archived 20 أكتوبر 2011 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ قالب:Cite Polish law

- ^ أ ب Adolf Pawiński, Mazowsze, Warszawa 1895, p. 37 (in Polish)

- ^ أ ب ت ث Płock : Local History Archived 13 ديسمبر 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Virtual Shtetl website, accessed 28 October 2013

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ "Płock". Encyklopedia PWN (in البولندية). Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Get to know Płock". From official Płock website.en. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز "Z dziejów Płocka". Małachowianka OnLine (in البولندية). Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Erlich, Ludwik (1968). Pisma wybrane Pawła Włodkowica (Preface). Warsaw: PAX. p. 13.

- ^ أ ب ت "Rocznica odznaczenia Płocka Krzyżem Walecznych za obronę przed bolszewikami". Onet (in البولندية). Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ de:Landkreis Schröttersburg

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, IPN, Warszawa, 2009, p. 224-225 (in Polish)

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 225-226

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 230

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 231

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 231-232

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 236

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 233

- ^ Maria Wardzyńska, Wysiedlenia ludności polskiej z okupowanych ziem polskich włączonych do III Rzeszy w latach 1939-1945, IPN, Warszawa, 2017, p. 383, 406 (in Polish)

- ^ "Außenkommando "Große Allee" des Strafgefängnisses Schröttersburg". Bundesarchiv.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Außenkommando des Strafgefängnisses Schröttersburg in Bauzug". Bundesarchiv.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Arbeitserziehungslager Schröttersburg-Süd". Bundesarchiv.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Kołakowski, Andrzej (2020). "Zbrodnia bez kary: eksterminacja dzieci polskich w okresie okupacji niemieckiej w latach 1939-1945". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in البولندية). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 78.

- ^ Drywa, Danuta (2020). "Germanizacja dzieci i młodzieży polskiej na Pomorzu Gdańskim z uwzględnieniem roli obozu koncentracyjnego Stutthof". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in البولندية). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 187.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. Volume II 22–24. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- ^ أ ب Maria Wardzyńska, Wysiedlenia ludności polskiej z okupowanych ziem polskich włączonych do III Rzeszy w latach 1939-1945, p. 381

- ^ أ ب Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, p. 224

- ^ "Widziałam egzekucję jako dziecko [FOTO]". PortalPłock (in البولندية). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rubel, Franz (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ "Średnia dobowa temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia minimalna temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia maksymalna temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Miesięczna suma opadu". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Liczba dni z opadem >= 0,1 mm". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia grubość pokrywy śnieżnej". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^

"Liczba dni z pokrywą śnieżna > 0 cm". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 21 يناير 2022 suggested (help) - ^ "Średnia suma usłonecznienia (h)". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in البولندية). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Płock Absolutna temperatura maksymalna" (in البولندية). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Płock Absolutna temperatura minimalna" (in البولندية). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Płock Średnia wilgotność" (in البولندية). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ Shrine of the Divine Mercy in Plock

- ^ أ ب ت ث Plock: Jewish Community before 1989 Archived 13 ديسمبر 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Virtual Shtetl, accessed 28 October 2013

- ^ أ ب ت Płock: Demography Archived 13 ديسمبر 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Virtual Shtetl, accessed 28 October 2013

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. Volume II, 22–23. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- ^ Kassow, Samuel D. "Vilna Stories". Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Samuel D. Gruber, "Poland: Płock Synagogue Reopens as a Museum", Samuel Gruber's Jewish Art and Monuments blog, accessed 28 October 2013

- ^ "Jak kręcili filmy w Płocku, kto kogo uderzył w twarz i dlaczego". PortalPłock (in البولندية). Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Kiełbasa tumska". Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi - Portal Gov.pl (in البولندية). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Baleron płocki". Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi - Portal Gov.pl (in البولندية). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ kmplock.eu

- ^ "Pksplock.com". Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Mostwplocku.blogspot.com

- ^ "Miasta partnerskie". Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "Städtepartnerschaften und Internationales". Büro für Städtepartnerschaften und internationale Beziehungen (in الألمانية). Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ^ "Płock zawiesza partnerską współpracę z rosyjskimi i białoruskimi miastami" (in البولندية). Retrieved 13 March 2022.

المراجع

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with پولندية-language sources (pl)

- CS1 البولندية-language sources (pl)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing پولندية-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- پووتسك

- Cities and towns in Masovian Voivodeship

- City counties of Poland

- Former capitals of Poland

- محافظة پووتسك

- Warsaw Voivodeship (1919–1939)

- Holocaust locations in Poland