الإنگليزية القديمة

| الإنگليزية القديمة | |

|---|---|

| Englisċ | |

| |

| النطق | [ˈeŋɡliʃ] |

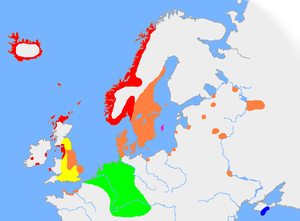

| المنطقة | إنگلترة (ماعدا الأطراف القصوى الجنوبية الغربية والشمالية الغربية)، جنوب وشرق اسكتلندة، والأطراف الشرقية من ويلز الحديثة. |

| الحقبة | تطور معظمها إلى الإنگليزية الوسيطة و الاسكوت المبكرة بحلول القرن الثالث عشر |

الصيغ المبكرة | |

| اللهجات | |

| الرونية، ولاحقاً اللاتينية (أبجدية الإنگليزية القديمة). | |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | ang |

| ISO 639-2 | ang |

| ISO 639-3 | ang |

| ISO 639-6 | ango |

| Glottolog | olde1238 |

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الإنگليزية القديمة |

|---|

الإنگليزية القديمة (Old English ؛ Englisċ؛ تـُنطق [ˈeŋɡliʃ])، أو الأنگلو-ساكسونية Anglo-Saxon،[1] هي أقدم صيغة مسجلة للغة الإنگليزية، المحكية في إنگلترة وجنوب وشرق اسكتلندة في مطلع العصور الوسطى. وقد جلبها إلى بريطانيا العظمى المستوطنون الأنگلو-ساكسون في منتصف القرن الخامس، وتعود أوائل الأعمال الأدبية بالإنگليزية القديمة إلى منتصف القرن السابع. وبعد الفتح النورماني في 1066، اِستُبدِلت الإنگليزية، لبعض الوقت، كلغة الطبقات العليا بالأنگلو-نورمانية، التي هي قريبة من الفرنسية. وهذا ما اِعتُبِر علامة على نهاية عصر الإنگليزية القديمة، إذ أثناء تلك الفترة تأثرت اللغة الإنگليزية بشدة بالأنگلو-نورمانية، فتطورت إلى طَور يُعرف الآن بإسم الإنگليزية الوسيطة في إنگلترة و الاسكوت المبكرة في اسكتلندة.

تطورت الإنگليزية القديمة من فئة من اللهجات الأنگلو-فريزية أو إنگڤايونية التي كان تتكلمها أصلاً القبائل الجرمانية المعروفة تقليدياً بإسم الأنگل و الساكسون و الجوت. As such, Old English was a "thoroughly Germanic cousin of Dutch and German", unrecognisable as English today.[2] As the Germanic settlers became dominant in England, their language replaced the languages of Roman Britain: Common Brittonic, a Celtic language, and Latin, brought to Britain by Roman invasion. Old English had four main dialects, associated with particular Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish and West Saxon. It was West Saxon that formed the basis for the literary standard of the later Old English period,[3] although the dominant forms of Middle and Modern English would develop mainly from Mercian, and Scots from Northumbrian. The speech of eastern and northern parts of England was subject to strong Old Norse influence due to Scandinavian rule and settlement beginning في القرن التاسع.

الإنگليزية القديمة هي واحدة من اللغات الجرمانية الغربية، وأقرب أقاربها هم الفريزية القديمة و الساكسونية القديمة. Like other old Germanic languages, it is very different from Modern English and Modern Scots, and impossible for Modern English or Modern Scots speakers to understand without study. Within Old English grammar nouns, adjectives, pronouns and verbs have many inflectional endings and forms, and word order is much freer.[3] أقدم نقوش بالإنگليزية القديمة كانت مكتوبة باستخدام نظام روني، ولكن منذ نحو القرن الثامن اِستُبدِل ذلك بنسخة من الأبجدية اللاتينية.

أصل الاسم

Englisc, from which the word English is derived, means 'pertaining to the Angles'.[4] In Old English, this word was derived from Angles (one of the Germanic tribes who conquered parts of Great Britain in the 5th century).[5] During the 9th century, all invading Germanic tribes were referred to as Englisc. It has been hypothesised that the Angles acquired their name because their land on the coast of Jutland (now mainland Denmark) resembled a fishhook. Proto-Germanic *anguz also had the meaning of 'narrow', referring to the shallow waters near the coast. That word ultimately goes back to Proto-Indo-European *h₂enǵʰ-, also meaning 'narrow'.[6]

Another theory is that the derivation of 'narrow' is the more likely connection to angling (as in fishing), which itself stems from a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root meaning bend, angle.[7] The semantic link is the fishing hook, which is curved or bent at an angle.[8] In any case, the Angles may have been called such because they were a fishing people or were originally descended from such, and therefore England would mean 'land of the fishermen', and English would be 'the fishermen's language'.[9]

التاريخ

اللهجات

الصوتيات

The inventory of Early West Saxon surface phones is as follows.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | (n̥) n | (ŋ) | ||||

| Stop | p b | t d | k (ɡ) | ||||

| Affricate | tʃ (dʒ) | ||||||

| Fricative | f (v) | θ (ð) | s (z) | ʃ | (ç) | x ɣ | (h) |

| Approximant | (l̥) l | j | (w̥) w | ||||

| Trill | (r̥) r |

الكتابة

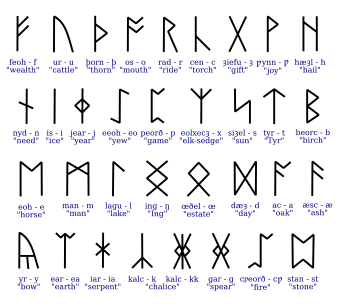

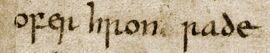

Old English was first written in runes, using the futhorc—a rune set derived from the Germanic 24-character elder futhark, extended by five more runes used to represent Anglo-Saxon vowel sounds and sometimes by several more additional characters. From around the 8th century, the runic system came to be supplanted by a (minuscule) half-uncial script of the Latin alphabet introduced by Irish Christian missionaries.[10] This was replaced by Insular script, a cursive and pointed version of the half-uncial script. This was used until the end of the 12th century when continental Carolingian minuscule (also known as Caroline) replaced the insular.

The Latin alphabet of the time still lacked the letters ⟨j⟩ and ⟨w⟩, and there was no ⟨v⟩ as distinct from ⟨u⟩; moreover native Old English spellings did not use ⟨k⟩, ⟨q⟩ or ⟨z⟩. The remaining 20 Latin letters were supplemented by four more: ⟨æ⟩ (æsc, modern ash) and ⟨ð⟩ (ðæt, now called eth or edh), which were modified Latin letters, and thorn ⟨þ⟩ and wynn ⟨ƿ⟩, which are borrowings from the futhorc. A few letter pairs were used as digraphs, representing a single sound. Also used was the Tironian note ⟨⁊⟩ (a character similar to the digit 7) for the conjunction and. A common scribal abbreviation was a thorn with a stroke ⟨ꝥ⟩, which was used for the pronoun þæt. Macrons over vowels were originally used not to mark long vowels (as in modern editions), but to indicate stress, or as abbreviations for a following m or n.[11][12]

Modern editions of Old English manuscripts generally introduce some additional conventions. The modern forms of Latin letters are used, including ⟨g⟩ in place of the insular G, ⟨s⟩ for long S, and others which may differ considerably from the insular script, notably ⟨e⟩, ⟨f⟩ and ⟨r⟩. Macrons are used to indicate long vowels, where usually no distinction was made between long and short vowels in the originals. (In some older editions an acute accent mark was used for consistency with Old Norse conventions.) Additionally, modern editions often distinguish between velar and palatal ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ by placing dots above the palatals: ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩. The letter wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ is usually replaced with ⟨w⟩, but æsc, eth and thorn are normally retained (except when eth is replaced by thorn).

In contrast with Modern English orthography, that of Old English was reasonably regular, with a mostly predictable correspondence between letters and phonemes. There were not usually any silent letters—in the word cniht, for example, both the ⟨c⟩ and ⟨h⟩ were pronounced, unlike the ⟨k⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ in the modern knight. The following table lists the Old English letters and digraphs together with the phonemes they represent, using the same notation as in the Phonology section above.

| الحرف | IPA transcription | الوصف وملاحظات |

|---|---|---|

| a | /ɑ/, /ɑː/ | Spelling variations like ⟨land⟩ ~ ⟨lond⟩ ("land") suggest the short vowel had a rounded allophone [ɒ] before /m/ and /n/ when it occurred in stressed syllables. |

| ā | /ɑː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /ɑ/. |

| æ | /æ/, /æː/ | Formerly the digraph ⟨ae⟩ was used; ⟨æ⟩ became more common during the 8th century, and was standard after 800. In 9th-century Kentish manuscripts, a form of ⟨æ⟩ that was missing the upper hook of the ⟨a⟩ part was used; it is not clear whether this represented /æ/ or /e/. See also ę. |

| ǣ | /æː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /æ/. |

| b | /b/ | |

| [v] (an allophone of /f/) | Used in this way in early texts (before 800). For example, the word "sheaves" is spelled scēabas in an early text, but later (and more commonly) as scēafas. | |

| c | /k/ | |

| /tʃ/ | The /tʃ/ pronunciation is sometimes written with a diacritic by modern editors: most commonly ⟨ċ⟩, sometimes ⟨č⟩ or ⟨ç⟩. Before a consonant letter the pronunciation is always /k/; word-finally after ⟨i⟩ it is always /tʃ/. Otherwise, a knowledge of the history of the word is needed to predict the pronunciation with certainty, although it is most commonly /tʃ/ before front vowels (other than [y]) and /k/ elsewhere. (For details, see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization.) See also the digraphs cg, sc. | |

| cg | [ddʒ], rarely [ɡɡ] | West Germanic gemination of Proto-Germanic *g resulted in the voiced palatal geminate /jj/ (phonetically [ddʒ]). Consequently, the voiced velar geminate /ɣɣ/ (phonetically [ɡɡ]) was rare in Old English, and its etymological origin in the words in which it occurs (such as frocga 'frog') is unclear.[13] Alternative spellings of either geminate included ⟨gg⟩, ⟨gc⟩, ⟨cgg⟩, ⟨ccg⟩ and ⟨gcg⟩.[14][15] The two geminates were not distinguished in Old English orthography; in modern editions, the palatal geminate is sometimes written ⟨ċġ⟩ to distinguish it from velar ⟨cg⟩.[16] |

| [dʒ] (the phonetic realization of /j/ after /n/) | After /n/, /j/ was realized as [dʒ] and /ɣ/ was realized as [ɡ]. The spellings ⟨ncg⟩, ⟨ngc⟩ and even ⟨ncgg⟩ were occasionally used instead of the usual ⟨ng⟩.[17] The cluster ending in the palatal affricate is sometimes written ⟨nċġ⟩ by modern editors. | |

| d | /d/ | In the earliest texts it also represented /θ/ (انظر þ). |

| ð | /θ/, including its allophone [ð] | Called ðæt in Old English; now called eth or edh. Derived from the insular form of ⟨d⟩ with the addition of a cross-bar. See also þ. |

| e | /e/, /eː/ | |

| ę | A modern editorial substitution for the modified Kentish form of ⟨æ⟩ (see æ). Compare e caudata, ę. | |

| ē | /eː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /e/. |

| ea | /æɑ̯/, /æːɑ̯/ | Sometimes stands for /ɑ/ after ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩ (see palatal diphthongization). |

| ēa | /æːɑ̯/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /æɑ̯/. Sometimes stands for /ɑː/ after ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩. |

| eo | /eo̯/, /eːo̯/ | Sometimes stands for /o/ after ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩ (see palatal diphthongization). |

| ēo | /eːo̯/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /eo̯/. |

| f | /f/, including its allophone [v] (but see b). | |

| g | /ɣ/, including its allophone [ɡ]; or /j/, including its allophone [dʒ], which occurs after ⟨n⟩. | In Old English manuscripts, this letter usually took its insular form ⟨ᵹ⟩ (see also: yogh). The [j] and [dʒ] pronunciations are sometimes written ⟨ġ⟩ in modern editions. Word-initially before another consonant letter, the pronunciation is always the velar fricative [ɣ]. Word-finally after ⟨i⟩, it is always palatal [j]. Otherwise, a knowledge of the history of the word in question is needed to predict the pronunciation with certainty, although it is most commonly /j/ before and after front vowels (other than [y]) and /ɣ/ elsewhere. (For details, see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization.) |

| h | /x/, including its allophones [h, ç] | The combinations ⟨hl⟩, ⟨hr⟩, ⟨hn⟩, ⟨hw⟩ may have been realized as devoiced versions of the second consonants instead of as sequences starting with [h]. |

| i | /i/, /iː/ | |

| ī | /iː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /i/. |

| ie | /iy̯/, /iːy̯/ | |

| īe | /iːy̯/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /iy̯/. |

| io | /io̯/, /iːo̯/ | By the time of the first written prose, /i(ː)o̯/ had merged with /e(ː)o̯/ in every dialect but Northumbrian, where it was preserved until Middle English. In Early West Saxon /e(ː)o̯/ was often written ⟨io⟩ instead of ⟨eo⟩, but by Late West Saxon only the ⟨eo⟩ spelling remained common. |

| k | /k/ | Rarely used; this sound is normally represented by ⟨c⟩. |

| l | /l/ | Probably velarised [ɫ] (as in Modern English) when in coda position. |

| m | /m/ | |

| n | /n/, including its allophone [ŋ]. | |

| o | /o/, /oː/ | See also a. |

| ō | /oː/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /o/. |

| oe | /ø/, /øː/ (in dialects having that sound). | |

| ōe | /øː/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /ø/. |

| p | /p/ | |

| qu | /kw/ | A rare spelling of /kw/, which was usually written as ⟨cƿ⟩ (⟨cw⟩ in modern editions). |

| r | /r/ | The exact nature of Old English /r/ is not known; it may have been an alveolar approximant [ɹ] as in most modern English, an alveolar flap [ɾ], or an alveolar trill [r]. |

| s | /s/, including its allophone [z]. | |

| sc | /ʃ/ or occasionally /sk/. | /ʃ/ is always geminate /ʃ:/ between vowels: thus fisċere (“fisherman”) was pronounced /ˈfiʃ.ʃe.re/. Also, ⟨sc⟩ is pronounced /sk/ non-word-initially if the next sound had been a back vowel (/ɑ/, /o/, /u/) at the time of palatalization,[18] giving rise to contrasts such as fisċ /fiʃ/ (“fish”) next to its plural fiscas /ˈfis.kɑs/. See palatalization. |

| t | /t/ | |

| th | Represented /θ/ in the earliest texts (see þ). | |

| þ | /θ/, including its allophone [ð] | Called thorn and derived from the rune of the same name. In the earliest texts ⟨d⟩ or ⟨th⟩ was used for this phoneme, but these were later replaced in this function by eth ⟨ð⟩ and thorn ⟨þ⟩. Eth was first attested (in definitely dated materials) in the 7th century, and thorn in the 8th. Eth was more common than thorn before Alfred's time. From then onward, thorn was used increasingly often at the start of words, while eth was normal in the middle and at the end of words, although usage varied in both cases. Some modern editions use only thorn. See also Pronunciation of English ⟨th⟩. |

| u | /u/, /uː/. Also sometimes /w/ (see ƿ, below). | |

| uu | Sometimes used for /w/ (see ƿ, below). | |

| ū | Used for /uː/ in modern editions, to distinguish from short /u/. | |

| w | /w/ | A modern substitution for ⟨ƿ⟩. |

| ƿ | /w/ | Called wynn and derived from the rune of the same name. In earlier texts by continental scribes, and also later in the north, /w/ was represented by ⟨u⟩ or ⟨uu⟩. In modern editions, wynn is replaced by ⟨w⟩, to prevent confusion with ⟨p⟩. |

| x | /ks/. | |

| y | /y/, /yː/. | |

| ȳ | /yː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /y/. |

| z | /ts/ | A rare spelling for /ts/; e.g. betst ("best") is occasionally spelt bezt. |

| الأصل | Representation with constructed cognates | |

| 1 | Hƿæt! ƿē Gār-Dena in ġeār-dagum, | What! We of Gare-Danes (lit. Spear-Danes) in yore-days, |

| þēod-cyninga, þrym ġefrūnon, | of thede (nation/people)-kings, did thrum (glory) frayne (learn about by asking), | |

| hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon. | how those athelings (noblemen) did ellen (fortitude/courage/zeal) freme (promote). | |

| Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum, | Oft did Scyld Scefing of scather threats (troops), | |

| 5 | monegum mǣġþum, meodosetla oftēah, | of many maegths (clans; cf. Irish cognate Mac-), of mead-settees atee (deprive), |

| egsode eorlas. Syððan ǣrest ƿearð | [and] ugg (induce loathing in, terrify; related to "ugly") earls. Sith (since, as of when) erst (first) [he] worthed (became) | |

| fēasceaft funden, hē þæs frōfre ġebād, | [in] fewship (destitute) found, he of this frover (comfort) abode, | |

| ƿēox under ƿolcnum, ƿeorðmyndum þāh, | [and] waxed under welkin (firmament/clouds), [and amid] worthmint (honour/worship) threed (throve/prospered) | |

| oðþæt him ǣġhƿylc þāra ymbsittendra | oth that (until that) him each of those umsitters (those "sitting" or dwelling roundabout) | |

| 10 | ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde, | over whale-road (kenning for "sea") hear should, |

| gomban gyldan. Þæt ƿæs gōd cyning! | [and] yeme (heed/obedience; related to "gormless") yield. That was [a] good king! |

صلاة الرب

هذا النص من صلاة الرب معروض باللهجة الساكسونية الغربية المبكرة القياسية.

| السطر | الأصل | IPA | الترجمة |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Fæder ūre þū þe eart on heofonum, | [ˈfæ.der ˈuː.re θuː θe æɑ̯rt on ˈheo̯.vo.num] | Our father, you who are in heaven, |

| [2] | Sīe þīn nama ġehālgod. | [siːy̯ θiːn ˈnɒ.mɑ jeˈhɑːɫ.ɣod] | May your name be hallowed. |

| [3] | Tōbecume þīn rīċe, | [ˌtoː.beˈku.me θiːn ˈriː.t͡ʃe] | May your kingdom come, |

| [4] | Ġeweorðe þīn willa, on eorðan swā swā on heofonum. | [jeˈweo̯rˠ.ðe θiːn ˈwil.lɑ on ˈeo̯rˠ.ðan swɑː swɑː on ˈheo̯.vo.num] | Your will be done, on Earth as in heaven. |

| [5] | Ūrne dæġhwamlīcan hlāf sele ūs tōdæġ, | [ˈuːrˠ.ne ˈdæj.ʍɑmˌliː.kɑn hl̥ɑːf ˈse.le uːs toːˈdæj] | Give us our daily bread today, |

| [6] | And forġief ūs ūre gyltas, swā swā wē forġiefaþ ūrum gyltendum. | [ɒnd forˠˈjiy̯f uːs ˈuː.re ˈɣyl.tɑs swɑː swɑː weː forˠˈjiy̯.vɑθ uː.rum ˈɣyl.ten.dum] | And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors. |

| [7] | And ne ġelǣd þū ūs on costnunge, ac ālīes ūs of yfele. | [ɒnd ne jeˈlæːd θuː uːs on ˈkost.nuŋ.ɡe ɑk ɑːˈliːy̯s uːs of ˈy.ve.le] | And do not lead us into temptation, but rescue us from evil. |

| [8] | Sōðlīċe. | [ˈsoːðˌliː.t͡ʃe] | آمين. |

ميثاق كنوث

This is a proclamation from King Cnut the Great to his earl Thorkell the Tall and the English people written in AD 1020. Unlike the previous two examples, this text is prose rather than poetry. For ease of reading, the passage has been divided into sentences while the pilcrows represent the original division.

| الأصل | Representation with constructed cognates |

|---|---|

| ¶ Cnut cyning gret his arcebiscopas and his leod-biscopas and Þurcyl eorl and ealle his eorlas and ealne his þeodscype, tƿelfhynde and tƿyhynde, gehadode and læƿede, on Englalande freondlice. | ¶ Cnut, king, greets his archbishops and his lede'(people's)'-bishops and Thorkell, earl, and all his earls and all his peopleship, greater (having a 1200 shilling weregild) and lesser (200 shilling weregild), hooded(ordained to priesthood) and lewd(lay), in England friendly. |

| And ic cyðe eoƿ, þæt ic ƿylle beon hold hlaford and unsƿicende to godes gerihtum and to rihtre ƿoroldlage. | And I kithe(make known/couth to) you, that I will be [a] hold(civilised) lord and unswiking(uncheating) to God's rights(laws) and to [the] rights(laws) worldly. |

| ¶ Ic nam me to gemynde þa geƿritu and þa ƿord, þe se arcebiscop Lyfing me fram þam papan brohte of Rome, þæt ic scolde æghƿær godes lof upp aræran and unriht alecgan and full frið ƿyrcean be ðære mihte, þe me god syllan ƿolde. | ¶ I nam(took) me to mind the writs and the word that the Archbishop Lyfing me from the Pope brought of Rome, that I should ayewhere(everywhere) God's love(praise) uprear(promote), and unright(outlaw) lies, and full frith(peace) work(bring about) by the might that me God would(wished) [to] sell'(give). |

| ¶ Nu ne ƿandode ic na minum sceattum, þa hƿile þe eoƿ unfrið on handa stod: nu ic mid-godes fultume þæt totƿæmde mid-minum scattum. | ¶ Now, ne went(withdrew/changed) I not my shot(financial contribution, cf. Norse cognate in scot-free) the while that you stood(endured) unfrith(turmoil) on-hand: now I, mid(with) God's support, that [unfrith] totwemed(separated/dispelled) mid(with) my shot(financial contribution). |

| Þa cydde man me, þæt us mara hearm to fundode, þonne us ƿel licode: and þa for ic me sylf mid-þam mannum þe me mid-foron into Denmearcon, þe eoƿ mæst hearm of com: and þæt hæbbe mid-godes fultume forene forfangen, þæt eoƿ næfre heonon forð þanon nan unfrið to ne cymð, þa hƿile þe ge me rihtlice healdað and min lif byð. | Tho(then) [a] man kithed(made known/couth to) me that us more harm had found(come upon) than us well liked(equalled): and tho(then) fore(travelled) I, meself, mid(with) those men that mid(with) me fore(travelled), into Denmark that [to] you most harm came of(from): and that[harm] have [I], mid(with) God's support, afore(previously) forefangen(forestalled) that to you never henceforth thence none unfrith(breach of peace) ne come the while that ye me rightly hold(behold as king) and my life beeth. |

انظر أيضاً

- Exeter Book

- Go (verb)

- History of the Scots language

- I-mutation

- Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law Anglo-Frisian nasal spirant law

- List of generic forms in place names in the United Kingdom and Ireland

- List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents in English

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ بحلول القرن 16 أصبح المصطلح Anglo-Saxon يشير إلى كل شيء متعلق بالفترة الإنگليزية المبكرة، بما في ذلك اللغة والثقافة والشعب. بينما بقي كمصطلح معتاد للأمرَين الأخيرَين، فإن اللغة بدأ يُطلَق عليها الإنگليزية القديمة في نهاية القرن التاسع عشر، ونتيجة للمشاعر القومية المتزايدة ضد الجرمان في المجتمع الإنگليزي في ع1890 ومطلع ع1900. إلا أن العديد من المؤلفين ظلوا يستخدمون المصطلح الأنگلو-ساكسونية للإشارة للغة.

Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53033-4. - ^ "Why is the English spelling system so weird and inconsistent? | Aeon Essays". Aeon (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-08-11.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:2 - ^ Fennell, Barbara 1998. A history of English. A sociolinguistic approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ^ Pyles, Thomas and John Algeo 1993. Origins and development of the English language. 4th edition. (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich).

- ^ Barber, Charles, Joan C. Beal and Philip A. Shaw 2009. The English language. A historical introduction. Second edition of Barber (1993). Cambridge: University Press.

- ^ Mugglestone, Lynda (ed.) 2006. The Oxford History of English. Oxford: University Press.

- ^ Hogg, Richard M. and David Denison (ed.) 2006. A history of the English language. Cambridge: University Press.

- ^ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable 1993 A history of the English language. 4th edition. (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall).

- ^ Crystal, David (1987). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-521-26438-3.

- ^ C.M. Millward, Mary Hayes, A Biography of the English Language, Cengage Learning 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Stephen Pollington, First Steps in Old English, Anglo-Saxon Books 1997, p. 138.

- ^ Minkova (2014), p. 79.

- ^ Wełna (1986), p. 755.

- ^ Shaw (2012), p. 51

- ^ Hogg (1992), p. 91.

- ^ Wełna (1986), pp. 754-755.

- ^ Hogg (1992), p. 257

ببليوگرافيا

- مصادر

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1955). English Historical Documents. Vol. I: c. 500–1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- عامة

- Baker, Peter S (2003). Introduction to Old English. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23454-3.

- Baugh, Albert C; & Cable, Thomas. (1993). A History of the English Language (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

- Blake, Norman (1992). The Cambridge History of the English Language: Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Earle, John (2005). A Book for the Beginner in Anglo-Saxon. Bristol, PA: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889758-69-8. (Reissue of one of 4 eds. 1877–1902)

- Euler, Wolfram (2013). Das Westgermanische : von der Herausbildung im 3. bis zur Aufgliederung im 7. Jahrhundert; Analyse und Rekonstruktion (West Germanic: from its Emergence in the 3rd up until its Dissolution in the 7th century CE: Analyses and Reconstruction). 244 p., in German with English summary, London/Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8.

- Hogg, Richard M. (ed.). (1992). The Cambridge History of the English Language: (Vol 1): the Beginnings to 1066. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hogg, Richard; & Denison, David (eds.) (2006) A History of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jespersen, Otto (1909–1949) A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. 7 vols. Heidelberg: C. Winter & Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard

- Lass, Roger (1987) The Shape of English: structure and history. London: J. M. Dent & Sons

- Lass, Roger (1994). Old English: A historical linguistic companion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43087-9.

- Magennis, Hugh (2011). The Cambridge Introduction to Anglo-Saxon Literature. Cambridge University Press.

- Millward, Celia (1996). A Biography of the English Language. Harcourt Brace. ISBN 0-15-501645-8.

- Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C (2001). A Guide to Old English (6th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22636-2.

- Quirk, Randolph; & Wrenn, CL (1957). An Old English Grammar (2nd ed.) London: Methuen.

- Ringe, Donald R and Taylor, Ann (2014). The Development of Old English: A Linguistic History of English, vol. II, ISBN 978-0199207848. Oxford.

- Strang, Barbara M. H. (1970) A History of English. London: Methuen.

- تاريخ خارجي

- Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and Its Closest Relatives. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2221-8.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. (2009). An Introduction to Old Frisian. History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Stenton, FM (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- الكتابة/النقوش القديمة

- Bourcier, Georges. (1978). L'orthographie de l'anglais: Histoire et situation actuelle. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Elliott, Ralph WV (1959). Runes: An introduction. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Keller, Wolfgang. (1906). Angelsächsische Paleographie, I: Einleitung. Berlin: Mayer & Müller.

- Ker, NR (1957). A Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ker, NR (1957: 1990). A Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon; with supplement prepared by Neil Ker originally published in Anglo-Saxon England; 5, 1957. Oxford: Clarendon Press ISBN 0-19-811251-3

- Page, RI (1973). An Introduction to English Runes. London: Methuen.

- Scragg, Donald G (1974). A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Shaw, Philip A (2012). "Coins As Evidence". The Oxford Handbook of the History of English, Chapter 3, pp. 50–52. Edited by Terttu Nevalainen and Elizabeth Closs Traugott.

- Wełna, Jerzy (1986). "The Old English Digraph ⟨cg⟩ Again". Linguistics across Historical and Geographical Boundaries: Vol 1: Linguistic Theory and Historical Linguistics (pp. 753–762). Edited by Dieter Kastovsky and Aleksander Szwedek.

- الصوتيات

- Anderson, John M; & Jones, Charles. (1977). Phonological structure and the history of English. North-Holland linguistics series (No. 33). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Brunner, Karl. (1965). Altenglische Grammatik (nach der angelsächsischen Grammatik von Eduard Sievers neubearbeitet) (3rd ed.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Cercignani, Fausto (1983). "The Development of */k/ and */sk/ in Old English". Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 82 (3): 313–323.

- Girvan, Ritchie. (1931). Angelsaksisch Handboek; E. L. Deuschle (transl.). (Oudgermaansche Handboeken; No. 4). Haarlem: Tjeenk Willink.

- Halle, Morris; & Keyser, Samuel J. (1971). English Stress: its form, its growth, and its role in verse. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hockett, Charles F (1959). "The stressed syllabics of Old English". Language. 35 (4): 575–597. doi:10.2307/410597. JSTOR 410597.

- Hogg, Richard M. (1992). A Grammar of Old English, I: Phonology. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Kuhn, Sherman M (1961). "On the Syllabic Phonemes of Old English". Language. 37 (4): 522–538. doi:10.2307/411354. JSTOR 411354.

- Kuhn, Sherman M. (1970). "On the consonantal phonemes of Old English". In: J. L. Rosier (ed.) Philological Essays: studies in Old and Middle English language and literature in honour of Herbert Dean Merritt (pp. 16–49). The Hague: Mouton.

- Lass, Roger; & Anderson, John M. (1975). Old English Phonology. (Cambridge studies in linguistics; No. 14). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Luick, Karl. (1914–1940). Historische Grammatik der englischen Sprache. Stuttgart: Bernhard Tauchnitz.

- Maling, J (1971). "Sentence stress in Old English". Linguistic Inquiry. 2 (3): 379–400. JSTOR 4177642.

- McCully, CB; Hogg, Richard M (1990). "An account of Old English stress". Journal of Linguistics. 26 (2): 315–339. doi:10.1017/S0022226700014699.

- Minkova, Donka (2014). A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh University Press.

- Moulton, WG (1972). "The Proto-Germanic non-syllabics (consonants)". In: F van Coetsem & HL Kufner (Eds.), Toward a Grammar of Proto-Germanic (pp. 141–173). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Sievers, Eduard (1893). Altgermanische Metrik. Halle: Max Niemeyer.

- Wagner, Karl Heinz (1969). Generative Grammatical Studies in the Old English language. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.

- الشكل

- Brunner, Karl. (1965). Altenglische Grammatik (nach der angelsächsischen Grammatik von Eduard Sievers neubearbeitet) (3rd ed.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wagner, Karl Heinz. (1969). Generative grammatical studies in the Old English language. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.

- بناء الجمل

- Brunner, Karl. (1962). Die englische Sprache: ihre geschichtliche Entwicklung (Vol. II). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Kemenade, Ans van. (1982). Syntactic Case and Morphological Case in the History of English. Dordrecht: Foris.

- MacLaughlin, John C. (1983). Old English Syntax: a handbook. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Mitchell, Bruce. (1985). Old English Syntax (Vols. 1–2). Oxford: Clarendon Press (no more published)

- Vol.1: Concord, the parts of speech and the sentence

- Vol.2: Subordination, independent elements, and element order

- Mitchell, Bruce. (1990) A Critical Bibliography of Old English Syntax to the end of 1984, including addenda and corrigenda to "Old English Syntax" . Oxford: Blackwell

- Timofeeva, Olga. (2010) Non-finite Constructions in Old English, with Special Reference to Syntactic Borrowing from Latin, PhD dissertation, Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki, vol. LXXX, Helsinki: Société Néophilologique.

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. (1972). A History of English Syntax: a transformational approach to the history of English sentence structure. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Visser, F. Th. (1963–1973). An Historical Syntax of the English Language (Vols. 1–3). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- المعاجم

- Bosworth, J; & Toller, T. Northcote. (1898). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Based on Bosworth's 1838 dictionary, his papers & additions by Toller)

- Toller, T. Northcote. (1921). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Campbell, A. (1972). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Enlarged addenda and corrigenda. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Clark Hall, J. R.; & Merritt, H. D. (1969). A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cameron, Angus, et al. (ed.) (1983) Dictionary of Old English. Toronto: Published for the Dictionary of Old English Project, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto by the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1983/1994. (Issued on microfiche and subsequently as a CD-ROM and on the World Wide Web.)

وصلات خارجية

- Old English/Modern English Translator

- Old English (Anglo-Saxon) alphabet

- Old English Letters

- Downloadable Old English keyboard for Windows and Mac at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 يونيو 2010)

- Another downloadable keyboard for Windows computers

- Guide to using Old English computer characters (Unicode, HTML entities, etc.)

- The Germanic Lexicon Project

- An overview of the grammar of Old English at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 16 نوفمبر 2001)

- The Lord's Prayer in Old English from the 11th century (video link)

- Over 100 Old English poems are edited, annotated and linked to digital images of their manuscript pages, with modern translations, in the Old English Poetry in Facsimile Project: DM

- القواميس

- Bosworth and Toller, An Anglo-Saxon dictionary

- Old English – Modern English dictionary at the Wayback Machine (archived 2 يوليو 2005)

- Old English Glossary at the Wayback Machine (archived 22 فبراير 2012)

- Dictionary of Old English

- دروس

- Old English Online by Jonathan Slocum and Winfred P. Lehmann, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- The Electronic Introduction to Old English at the Wayback Machine (archived 7 سبتمبر 2015)

- Learn Old English with Leofwin

- Old English Made Easy at the Wayback Machine (archived 3 مايو 2009)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية القديمة (ح. 450-1100)-language text

- Languages with ISO6 code

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with plain IPA

- Pages with empty portal template

- Webarchive template other archives

- اللغات الإنگليزية

- لغات القرون الوسطى

- اللغة الإنگليزية القديمة

- Languages attested from the 5th century

- تأسيسات القرن الخامس في إنگلترة

- لغات انقرضت في القرن 13

- انحلالات القرن 13 في أوروپا

- جرمانية بحر الشمال