الفلزات الثقيلة

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الجدول الدوري |

|---|

الفلزات الثقيلة Heavy metal، لم يتم تعريفها بشكل مُحدد، إلا أنها بشكل عام عناصر تمتلك خواص فيزيائية مثل الفلزات الانتقالية، وبعض أشباه الفلزات، اللانثانيدات، الأكتينيدات.

وفي محاولات متعددة للوقوف على تعريف مُحدد للمعادن الثقيلة بعضها يعتمد على الكثافة، أو على العدد الذري، أو الوزن الذري، أو على بعض الخصائص الكيميائية ومستوى السُميّة.

وفي تقرير تقني للـ [2] IUPAC، اعتبر مصطلح المعادن الثقيلة " مصطلح مُضلل" بسبب التناقض في التعريفات، وعدم وجود "قاعدة علمية متماسكة" يُعتمد عليها عند الاصطلاح، حيث أن بعض المعادن الثقيلة يمكن أن تكون أخف أو أثقل من الكربون.

وهناك مصطلح بديل هو المعادن السامة إنگليزية: toxic metal، وهو ما اختلفت فيه الآراء، نظراً لعدم وجود تعريف دقيق.

تعريف شائع آخر يقوم على أساس وزن المعدن (ومن هنا يأتي اسم المعادن الثقيلة)، حيث ينطبق على جميع المعادن التي تزن أكثر من 5000 كجم/م³ ؛ مثل الرصاص والزنك والنحاس.

الفلزات الثقيلة موجودة بصورة طبيعية في النظام البيئي، مع اختلافات كبيرة في التركيز. لكن ازياد نسبها مؤخراً يرجع إلى المصادر الصناعية والنفايات الصناعية السائلة والنض أيونات المعادن من التربة إلى البحيرات والأنهار والأمطار الحمضية، والتلوث الحادث من النفايات المتأتية من الوقود بشكل خاص.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تعريفات

| Heat map of heavy metals in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Uut | Fl | Uup | Lv | Uus | Uuo | ||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||||||||||

| Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

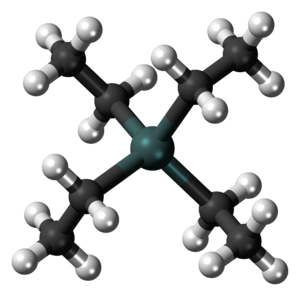

| This table shows the number of heavy metal criteria met by each metal, out of the ten criteria listed in this section i.e. two based on density, three on atomic weight, two on atomic number, and three on chemical behaviour.[n 1] It illustrates the lack of agreement surrounding the concept, with the possible exception of mercury, lead and bismuth. Six elements near the end of periods (rows) 4 to 7 sometimes considered metalloids are treated here as metals, including germanium (Ge), arsenic (As), selenium (Se), antimony (Sb), tellurium (Te), and astatine (At).[19][n 2] Ununoctium (Uuo) is treated as a nonmetal. Metals enclosed by a dashed line have (or, for At and elements 100–117, are predicted to have) densities of more than 5 g/cm3. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

List of heavy metals based on density

A density of more than 5 g/cm3 is sometimes mentioned as a common heavy metal defining factor[20] and, in the absence of a unanimous definition, is used to populate this list and (unless otherwise stated) guide the remainder of the article. Metalloids meeting the applicable criteria–arsenic and antimony for example—are sometimes counted as heavy metals, particularly in environmental chemistry,[21] as is the case here. Selenium (density 4.8 g/cm3)[22] is also included in the list. It falls marginally short of the density criterion and is less commonly recognised as a metalloid[19] but has a waterborne chemistry similar in some respects to that of arsenic and antimony.[23] Other metals sometimes classified or treated as "heavy" metals, such as beryllium[24] (density 1.8 gm/cm3),[25] aluminium[24] (2.7 gm/cm3),[26] calcium[27] (1.55 gm/cm3),[28] and barium[27] (3.6 gm/cm3)[29] are here treated as light metals and, in general, are not further considered.

| Produced mainly by commercial mining (informally classified by economic significance) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Produced mainly by artificial transmutation (informally classified by stability) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Biological role

| Element | Milligrams[36] | |

|---|---|---|

| Iron | 4000 | |

| Zinc | 2500 | |

| Lead[n 3] | 120 | |

| Copper | 70 | |

| Tin[n 4] | 30 | |

| Vanadium | 20 | |

| Cadmium | 20 | |

| Nickel[n 5] | 15 | |

| Selenium | 14 | |

| Manganese | 12 | |

| Other[n 6] | 200 | |

| Total | 7000 | |

Formation, abundance, occurrence, and extraction

| Heavy metals in the Earth's crust: | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abundance and main occurrence or source[n 7] | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | ||||

| 7 | Ra | ||||||||||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||

| Th | Pa | U | |||||||||||||||||

Most abundant (56300 ppm by weight)

|

Rare (0.01–0.99 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

Abundant (100–999 ppm)

|

Very rare (0.0001–0.0099 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

Uncommon (1–99 ppm)

|

Least abundant (~0.000001 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy metals left of the dividing line occur (or are sourced) mainly as lithophiles; those to the right, as chalcophiles except gold (a siderophile) and tin (a lithophile). | |||||||||||||||||||

Heavy metals up to the vicinity of iron (in the periodic table) are largely made via stellar nucleosynthesis. In this process, lighter elements from hydrogen to silicon undergo successive fusion reactions inside stars, releasing light and heat and forming heavier elements with higher atomic numbers.[44]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Properties compared with light metals

Some general physical and chemical properties of light and heavy metals are summarised in the table. The comparison should be treated with caution since the terms light metal and heavy metal are not always consistently defined. Also the physical properties of hardness and tensile strength can vary widely depending on purity, grain size and pre-treatment.[45]

| Physical properties | Light metals | Heavy metals |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Usually lower | Usually higher |

| Hardness[46] | Tend to be soft, easily cut or bent | Most are quite hard |

| Thermal expansivity[47] | Mostly higher | Mostly lower |

| Melting point | Mostly low[48] | Low to very high[49] |

| Tensile strength[50] | Mostly lower | Mostly higher |

| Chemical properties | Light metals | Heavy metals |

| Periodic table location | Most found in groups 1 and 2[51] | Nearly all found in groups 3 through 16 |

| Abundance in Earth's crust[41][52] | More abundant | Less abundant |

| Main occurrence (or source) | Lithophiles[43] | Lithophiles or chalcophiles (Au is a siderophile) |

| Reactivity[53][52] | More reactive | Less reactive |

| Sulfides | Soluble to insoluble[n 8] | Extremely insoluble[58] |

| Hydroxides | Soluble to insoluble[n 9] | Generally insoluble[62] |

| Salts[55] | Mostly form colourless solutions in water | Mostly form coloured solutions in water |

| Complexes | Mostly colourless[63] | Mostly coloured[64] |

| Biological role[65] | Include macronutrients (Na, Mg, K, Ca) | Include micronutrients (V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Mo) |

These properties make it relatively easy to distinguish a light metal like sodium from a heavy metal like tungsten, but the differences become less clear at the boundaries. Light structural metals like beryllium, scandium, and titanium have some of the characteristics of heavy metals, such as higher melting points;[n 10] post-transition heavy metals like zinc, cadmium, and lead have some of the characteristics of light metals, such as being relatively soft, and having lower melting points;[n 11] and forming mainly colourless complexes.[70][71][72]

Uses

Heavy metals are present in nearly all aspects of modern life. Iron may be the most common as it accounts for 90% of all refined metals. Platinum may be the most ubiquitous given it is said to be found in, or used to produce, 20% of all consumer goods.[73]

Some common uses of heavy metals depend on the general characteristics of metals such as electrical conductivity and reflectivity or the general characteristics of heavy metals such as density, strength, and durability. Other uses depend on the characteristics of the specific element, such as their biological role as nutrients or poisons or some other specific atomic properties. Examples of such atomic properties include: partly filled d- or f- orbitals (in many of the transition, lanthanide, and actinide heavy metals) that enable the formation of coloured compounds;[74] the capacity of most heavy metal ions (such as platinum,[75] cerium[76] or bismuth[77]) to exist in different oxidation states and therefore act as catalysts;[78] poorly overlapping 3d or 4f orbitals (in iron, cobalt, and nickel, or the lanthanide heavy metals from europium through thulium) that give rise to magnetic effects;[79] and high atomic numbers and electron densities that underpin their nuclear science applications.[80] Typical uses of heavy metals can be broadly grouped into the following six categories.[81][n 12]

Weight- or density-based

Some uses of heavy metals, including in sport, mechanical engineering, military ordnance, and nuclear science, take advantage of their relatively high densities. In underwater diving, lead is used as a ballast;[83] in handicap horse racing each horse must carry a specified lead weight, based on factors including past performance, so as to equalize the chances of the various competitors.[84] In golf, tungsten, brass, or copper inserts in fairway clubs and irons lower the centre of gravity of the club making it easier to get the ball into the air;[85] and golf balls with tungsten cores are claimed to have better flight characteristics.[86] In fly fishing, sinking fly lines have a PVC coating embedded with tungsten powder, so that they sink at the required rate.[87] In track and field sport, steel balls used in the hammer throw and shot put events are filled with lead in order to attain the minimum weight required under international rules.[88] Tungsten was used in hammer throw balls at least up to 1980; the minimum size of the ball was increased in 1981 to eliminate the need for what was, at that time, an expensive metal (triple the cost of other hammers) not generally available in all countries.[89] Tungsten hammers were so dense that they penetrated too deeply into the turf.[90]

In mechanical engineering, heavy metals are used for ballast in boats,[91] aeroplanes,[92] and motor vehicles;[93] or in balance weights on wheels and crankshafts,[94] gyroscopes, and propellers,[95] and centrifugal clutches,[96] in situations requiring maximum weight in minimum space (for example in watch movements).[92]

AM Russell and KL Lee

Structure–property relations

in nonferrous metals (2005, p. 16)

In military ordnance, tungsten or uranium is used in armour plating[97] and armour piercing projectiles,[98] as well as in nuclear weapons to increase efficiency (by reflecting neutrons and momentarily delaying the expansion of reacting materials).[99] In the 1970s, tantalum was found to be more effective than copper in shaped charge and explosively formed anti-armour weapons on account of its higher density, allowing greater force concentration, and better deformability.[100] Less-toxic heavy metals, such as copper, tin, tungsten, and bismuth, and probably manganese (as well as boron, a metalloid), have replaced lead and antimony in the green bullets used by some armies and in some recreational shooting munitions.[101] Doubts have been raised about the safety (or green credentials) of tungsten.[102]

Because denser materials absorb more radioactive emissions than lighter ones, heavy metals are useful for radiation shielding and to focus radiation beams in linear accelerators and radiotherapy applications.[103]

Strength- or durability-based

The strength or durability of heavy metals such as chromium, iron, nickel, copper, zinc, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, and lead, as well as their alloys, makes them useful for the manufacture of artefacts such as tools, machinery,[106] appliances,[107] utensils,[108] pipes,[107] railroad tracks,[109] buildings[110] and bridges,[111] automobiles,[107] locks,[112] furniture,[113] ships,[91] planes,[114] coinage[115] and jewellery.[116] They are also used as alloying additives for enhancing the properties of other metals.[n 14] Of the two dozen elements that have been used in the world's monetised coinage only two, carbon and aluminium, are not heavy metals.[118][n 15] Gold, silver, and platinum are used in jewellery[n 16] as are (for example) nickel, copper, indium, and cobalt in coloured gold.[121] Low-cost jewellery and children's toys may be made, to a significant degree, of heavy metals such as chromium, nickel, cadmium, or lead.[122]

Copper, zinc, tin, and lead are mechanically weaker metals but have useful corrosion prevention properties. While each of them will react with air, the resulting patinas of either various copper salts,[123] zinc carbonate, tin oxide, or a mixture of lead oxide, carbonate, and sulfate, confer valuable protective properties.[124] Copper and lead are therefore used, for example, as roofing materials;[125][n 17] zinc acts as an anti-corrosion agent in galvanised steel;[126] and tin serves a similar purpose on steel cans.[127]

The workability and corrosion resistance of iron and chromium are increased by adding gadolinium; the creep resistance of nickel is improved with the addition of thorium. Tellurium is added to copper and steel alloys to improve their machinability; and to lead to make it harder and more acid-resistant.[128]

Biological and chemical

The biocidal effects of some heavy metals have been known since antiquity.[130] Platinum, osmium, copper, ruthenium, and other heavy metals, including arsenic, are used in anti-cancer treatments, or have shown potential.[131] Antimony (anti-protozoal), bismuth (anti-ulcer), gold (anti-arthritic), and iron (anti-malarial) are also important in medicine.[132] Copper, zinc, silver, gold, or mercury are used in antiseptic formulations;[133] small amounts of some heavy metals are used to control algal growth in, for example, cooling towers.[134] Depending on their intended use as fertilisers or biocides, agrochemicals may contain heavy metals such as chromium, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, or lead.[135]

Selected heavy metals are used as catalysts in fuel processing (rhenium, for example), synthetic rubber and fibre production (bismuth), emission control devices (palladium), and in self-cleaning ovens (where cerium(IV) oxide in the walls of such ovens helps oxidise carbon-based cooking residues).[136] In soap chemistry, heavy metals form insoluble soaps that are used in lubricating greases, paint dryers, and fungicides (apart from lithium, the alkali metals and the ammonium ion form soluble soaps).[137]

Colouring and optics

The colours of glass, ceramic glazes, paints, pigments, and plastics are commonly produced by the inclusion of heavy metals (or their compounds) such as chromium, manganese, cobalt, copper, zinc, selenium, zirconium, molybdenum, silver, tin, praseodymium, neodymium, erbium, tungsten, iridium, gold, lead, or uranium.[139] Tattoo inks may contain heavy metals, such as chromium, cobalt, nickel, and copper.[140] The high reflectivity of some heavy metals is important in the construction of mirrors, including precision astronomical instruments. Headlight reflectors rely on the excellent reflectivity of a thin film of rhodium.[141]

Electronics, magnets, and lighting

Heavy metals or their compounds can be found in electronic components, electrodes, and wiring and solar panels where they may be used as either conductors, semiconductors, or insulators. Molybdenum powder is used in circuit board inks.[142] Ruthenium(IV) oxide coated titanium anodes are used for the industrial production of chlorine.[143] Home electrical systems, for the most part, are wired with copper wire for its good conducting properties.[144] Silver and gold are used in electrical and electronic devices, particularly in contact switches, as a result of their high electrical conductivity and capacity to resist or minimise the formation of impurities on their surfaces.[145] The semiconductors cadmium telluride and gallium arsenide are used to make solar panels. Hafnium oxide, an insulator, is used as a voltage controller in microchips; tantalum oxide, another insulator, is used in capacitors in mobile phones.[146] Heavy metals have been used in batteries for over 200 years, at least since Volta invented his copper and silver voltaic pile in 1800.[147] Promethium, lanthanum, and mercury are further examples found in, respectively, atomic, nickel-metal hydride, and button cell batteries.[148]

Magnets are made of heavy metals such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, niobium, bismuth, praseodymium, neodymium, gadolinium, and dysprosium. Neodymium magnets are the strongest type of permanent magnet commercially available. They are key components of, for example, car door locks, starter motors, fuel pumps, and power windows.[149]

Heavy metals are used in lighting, lasers, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Flat panel displays incorporate a thin film of electrically conducting indium tin oxide. Fluorescent lighting relies on mercury vapour for its operation. Ruby lasers generate deep red beams by exciting chromium atoms; the lanthanides are also extensively employed in lasers. Gallium, indium, and arsenic;[150] and copper, iridium, and platinum are used in LEDs (the latter three in organic LEDs).[151]

Nuclear

Niche uses of heavy metals with high atomic numbers occur in diagnostic imaging, electron microscopy, and nuclear science. In diagnostic imaging, heavy metals such as cobalt or tungsten make up the anode materials found in x-ray tubes.[155] In electron microscopy, heavy metals such as lead, gold, palladium, platinum, or uranium are used to make conductive coatings and to introduce electron density into biological specimens by staining, negative staining, or vacuum deposition.[156] In nuclear science, nuclei of heavy metals such as chromium, iron, or zinc are sometimes fired at other heavy metal targets to produce superheavy elements;[157] heavy metals are also employed as spallation targets for the production of neutrons[158] or radioisotopes such as astatine (using lead, bismuth, thorium, or uranium in the latter case).[159]

مصادر التلوث

الآثار الضارة

التسمم بالفلزات الثقيلة هو الحالة المرضة الناجمة عن التراكم السُمي للمعادن الثقيلة في الأنسجة الرخوة ومن الأمثلة على هذا النمط من المعادن؛ الرصاص، الزئبق، الزرنيخ، النحاس، الكادميوم وغيرها. تدخل المعادن الثقيلة للجسم بتناول الغذاء أو الماء الملوثين بها كما يتم استنشاقه من الهواء أو امتصاصه عن طريق الجلد. ينتج التسمم بالفلزات الثقيلة عن ملامسة أو تناول تراكيز سُمية من الفلزات الثقيلة بشكل مقصود أو غير مقصود.[161]

الأعراض

تعتمد علامات وأعراض التسمم بالفلزات الثقيلة على طبيعة وكمية التسمم على النحو التالي:

- الغثيان والتقيؤ.

- الاسهال.

- ألم المعدة.

- الصداع.

- الطعم المعدني في الفم.

- ظهور خطوط زرقاء حول اللثة.

- ضعف المهارات المعرفية، الحركية واللغوية في الحالات الشديدة من التسمم.

التشخيص

يعتمد تشخيص التسمم بالفلزات الثقيلة على الفحوصات المخبرية للدم، البول اضافة إلى التصوير الاشعاعي، وتم اعتماد تراكيز سُمية للفلزات الثقيلة على النحو التالي:

- الرصاص: > 80 ميكروگرام/دسل.

- الزئبق: > 3.6 ميكروگرام/دسل في البول و15 ميكروگرام/دسل في البول.

- الزرنيخ: > 50 ميكروگرام/دسل في عينة البول التجميعية ويُمكن الكشف عنه بالتصوير الاشعاعي للبطن

- الثاليوم: 15- 20 مگ/كيلوگرام من وزن الجسم.

تقارير تاريخية (أمثلة)

في عام 1932، صرفت مياه الصرف الصحي في اليابان والتي كانت تحتوى على نسب عالية من الزئبق في ميناء مينيماتا، والذي نجم عنه التراكم الحيوي للزئبق في الكائنات البحرية، وظهور حالات من التسمم في عام 1952 والتي عُرفت باسم متلازمة مينيماتا.

الكادميوم

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الكادميوم

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الكادميوم

يوجد معدن الكادميوم في قشرة الأرض، ودائماً ما يتواجد مع الزنك. لا يمكن تجنبه في الصناعة كمنتج ثانوى حتمى من مستخلصات الزنك والرصاص والنحاس. وقبل استخدامه في الصناعة، فقد دخل البيئة بشكل أساسى من خلال التربة لأنه تم اكتشافه في المبيدات الحشرية والسماد.

ودخول معدن الكادميوم لجسم الإنسان يكون من خلال الأطعمة، والأطعمة الغنية به تزيد من تركيزه في جسم الإنسان ومن أمثلة هذه الأطعمة الكبد، عش الغراب (المشرووم)، المحار، الكاكاو، الطحالب البحرية الجافة، بلح البحر.

يتعرض الشخص لمعدلات الكادميوم العالية من التدخين. فتدخين التبغ ينقل تأثير الكادميوم للرئة ومن ثَّم يقوم الدم بنقله لباقى أعضاء الجسم بتأثيراته السامة.

والضرر يأتى أيضاً من خلال حياة الإنسان بجوار أماكن النفايات المحتوية عليه أو بالقرب من المصانع التى تطلق الكادميوم فث الهواء، أو الأشخاص التى تعمل في مجال صناعة التعدين. عندما يتنفس الشخص كميات كبيرة من الكادميوم فهذا يعمل على تدمير الرئتين بشكل حاد يؤدى إلى وفاة الإنسان فيما بعد. ينتقل معدن الكادميوم أولاً إلى الكبد من خلال الدم، وهناك يتحد مع البروتينات ليكون مركبات معقدة تنتقل بدورها للكلى. يتراكم معدن الكادميوم في الكلى حيث يدمر وظائفها ويسبب خروج البروتينات الأساسية والسكريات من الجسم ومزيد من التلف في أنسجة الكلى ويستغرق هذا مدة طويلة من الزمن ليحدث كل هذا الضمور في الكلى.

ومن الآثار السلبية على الصحة والمتسبب فيها معدن الكادميوم[162]:

- الإسهال

- آلام المعدة

- القىء الحاد

- كسور العظام

- اضطرابات في الجهاز التناسلى وفى بعض الأحيان حدوث العقم

- ضمور في الجهاز العصبى المركزى

- ضمور في وظائف الجهاز المناعي بالجسم

- اضطرابات نفسية

- احتمالية الإصابة بضمور في الصفات الوراثية، أو الإصابة بمرض السرطان

- إصابة الإنسان بالتسمم الغذائى من معدن الكادميوم يكون نادراً ويحدث بشكل أكبر من تلوث البيئة، أو الاستهلاك المزمن للأطعمة العالية بنسبة الكادميوم فيها

الزئبق

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الزئبق

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الزئبق

التسمم بالزئبق ،هو مرض ناتج عن التعرض للزئبق أو أحد مركباته.

الزئبق هو فلز ثقيل يوجد في عدة أشكال، كلها يمكن أن تحدث آثارًا سامة إذا كانت الجرعات عالية بما فيه الكفاية. والزئبق في حالته العادية Hg0 يوجد في صورة بخارية أو سائلة، في حالة تأينه الزئبق Hg22+ يتواجد في صورة أملاح غير عضوية، أما في حالة تأينه Hg2+ فقد يتواجد في صورة أملاح غير عضوية أو مركبات زئبق عضوية؛ وتختلف المجموعات الثلاث في آثارها. تشمل التأثيرات السامة تلف في خلايا المخ والكلى والرئتين.[163] وقد يؤدي التسمم بالزئبق إلى العديد من الأمراض، بما في ذلك مرض الزهري[164] ومتلازمة هانتر-راسل وداء ميناماتا.[165]

أعراض التسمم بالزئبق عادة ما تشمل ضعف في الرؤية والسمع والتحدث، والإحساس بالانزعاج وعدم التوازن. وتختلف درجتها بحسب درجة السمية والجرعة وطريقة ومدة التعرض.

الرصاص

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الرصاص

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الرصاص

التسمم بالرصاص، هو مرض ينجم عن زيادة الرصاص في الجسم. وقد ينشأ عن ابتلاع الأجسام التي تحوي الرصاص، أو عن استنشاق غبار أو دخان الرصاص. وقد يتم امتصاص بعض أشكال الرصاص عن طريق الجلد.

يصيب التسمم بالرصاص كثيرًا من الأطفال الذين يأكلون قطعًا من الدهان الجاف الذي يحتوي على نسبة عالية من الرصاص. ويوجد مثل هذا الدهان في العديد من البيوت القديمة. ويصيب التسمم بالرصاص الكبار الذين يعملون في صهر المعادن وصناعة البطاريات والصناعات الأخرى التي تستخدم الرصاص. مثل هذه الصناعات يمكن أن تسبب تلوث البيئة بغبار الرصاص وغازاته التي يمكن أن تكون سببا لتسمّم الناس المقيمين قريبًا من المصانع. وثمة مصدر آخر للتلوث بالرصاص وهو الغازات المنطلقة من العربات التي تستعمل الوقود المعالج بالرصاص.

يعوق الرصاص إنتاج كريات الدم الحمراء، وقد يسبب تلفًا في الدماغ والكبد وأعضاء الجسد الأخرى. وتشمل أعراض التسمم بالرصاص فقر الدم، وحالات الصداع، والتهيُّج والضعف. كما يعاني العديد من المصابين من ألم البطن والقيء والإمساك وعدد من الأعراض التي تسمى أحيانًا المغص الرصاصي. وفي الحالات الحادة قد تعتري المصابين نوبات من التشنج والشلل. وقد تكون هذه الحالات قاتلة.

في أواخر سبعينيات القرن العشرين الميلادي وجد الباحثون أنه من الممكن أن يصاب الطفل بالأذى حتى بامتصاص جسده لكميّات قليلة من الرصاص عبر مدة طويلة. وعلى الرغم من أن مثل هذا الامتصاص لا يؤدّي إلى مرض جسدي، إلا أنه قد يصيب دماغ الطفل بتلف ينتُج عنه صعوبات في التعلم.

الكروم

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الكروم

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الكروم

يتعرض الإنسان لهذا التسمم بالتلامس الجلدى لمعدن الكروم أو مركباته. معدلات الكروم في المياه أو الهواء بوجه عام قليلة جداً، إلا ن مياه الآبار الملوثة به تحتوى على الكروم معظم ما يتناوله الفرد من هذا المعدن من خلال الأطعمة هو الكروم والمتوافر بشكل طبيعى في الخضراوات والفاكهة واللحوم والخميرة والحبوب. وطريقة تحضير الأطعمة والتخزين من الممكن أن تغير محتوى الكروم ونسبه، فإذا تم تخزين الكروم في تنكات أو علب حديدية فإن تركيزاته قد ترتفع. هذا النوع من الكروم هام لصحة الإنسان، وعدم حصول الإنسان على القدر الكافى منه يسبب اضطرابات للقلب، اضطرابات في عملية الآيض (التمثيل الغذائى)، الإصابة بالسكر. والكميات الزائدة منه تسبب اضطرابات صحية أيضاً مثل الطفح الجلدي.

الكروم ضار لصحة الإنسان ويمثل خطورة على الأشخاص التى تعمل في مجال صناعة الصلب والمنسوجات. أما الأشخاص التى تدخن التبغ تتعرض لنسب كبيرة من معدن الكروم، وعند استخدامه في الجلود قد يكون هناك رد فعل من الحساسية عند بعض الأشخاص مثل الطفح الجلدى. كما أن تنفسه يسبب اهتياج للأنف ونزيف منها.

أما المخاطر الأخرى المرتبطة بهذا المعدن:

- الطفح الجلدى

- اضطرابات المعدة والقرح

- اضطرابات في التنفس

- ضعف في كفاءة الجهاز المناعي

- ضمور في الكلى والكبد

- تغير في المواد الجينية

- سرطان الرئة

- الموت

وهذه المخاطر تعتمد على حالة التأكسد. والصورة المعدنية له تكون درجة سميتها ضئيلة، أما النوع السادس فهو سام. وتأثير هذا النوع على الجلد يتمثل في صورة حدوث الأعراض التالية: القرح، التهاب طبقة الجلد الخارجية، حساسية الجلد والاضطرابات المختلفة.

أما تنفسه من خلال الهواء فقد يسبب الآتى: ثقب في الغشاء المخاطى للحاجز الأنفى، اهتياج الحلق والحنجرة، التهاب الشعب الهوائية مسبباً أزمة الصدر، تشنجات الشعب الهوائية، الأوديما. ومن الأعراض التنفسية الأخرى: السعال، الأزيز، قصر التنفس، هرش بالأنف.

الزرنيخ

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الزرنيخ

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم الزرنيخ

أشتهر الزرنيخ علي مدي قرون طويلة بأنه أوسع السموم استخداماً في قتل الآخرين وقد نشأت هذه السمعة من كونه يتمتع بصفات ثلاث وهي:

أولاً: أن مركباته تكاد تكون بلا طعم ولا رائحة أولون مميز حيث يسهل تقديمها في مختلف الأطعمة والمشروبات دون أن تثير الريبة.

ثانيا: ظهور أعراض التسمم بالزرنيخ يبدأ بعد فترة قد تطول إلي حد يبتعد فيه الجاني عن المجني عليه.

ثالثاً: أن الأعراض التسممية الناشئة عنه تختلط مع كثير من الأمراض المعوية السارية بحيث لا تثير شكاً لدي الطبيب المعالج .

وقد فقد الزرنيخ هذه السمعة بسبب سهولة الكشف عن وجوده حتى بعد تحلل جثة المتسمم تحللاً كاملاً إذ يمكن الكشف عنه في عظامه أوقي التربة أسفل الجثة.

ويستخدم الزرنيخ في مبيدات الطحالب والقوارض والدهانات وورق الحائط وفي صناعة السيراميك والزجاج ومن أخطر مركبات الزرنيخ سمية (ثالث أكسيد الزرنيخ) وهو مسحوق قابل للذوبان في الماء والجرعة القاتلة منه تتراوح بين 60إلي 20 ملليجرام ويتم امتصاصه عن طريق الأمعاء ببطء حيث تظهر الأعراض بعد فترة زمنية تتراوح من ربع ساعة إلي عدة ساعات . وهناك صورة أخرى وهي غاز الزرنيخ ويتم امتصاصه عن طريق الاستنشاق إلي الدم مباشرة وتشكل كميات ضئيلة منه في الهواء المحيط خطراً شديداً إذ تؤدي إلي التسمم الحاد في صورة تحلل كريات الدم ويتولد الغاز من معالجة المعادن المحتوية علي شوائب الزرنيخ بالأحماض أثناء تنظيفها.

أعراض التسمم بالزرنيخ:عند التسمم بالزرنيخ بالفم يكون هناك إحساس بطعم قابض يعقبه بعد ابتلاعه فترة كمون لا يظهر بها أعراض تتراوح ما بين 15 دقيقة إلي بضع ساعات حسب محتوي المعدة من الطعام ونوعه ، إذ يؤخر وجود طعام دهني امتصاص الزرنيخ لفترات طويلة بينما يعجل الامتصاص تعاطي الزرنيخ علي صورة محلول في مشروب ساخن . وتبدأ أعراض التسمم علي شكل قيء شديد وإسهال شديد (يشبه الكوليرا) ينشأ عنه جفاف سريع وانهيار. ويصل أيون الزرنيخ الممتص إلي الأعضاء والأنسجة الداخلية للجسم ليفسد عمل النظم الإنزيمية المعتمدة في عملها علي مجموعات السلفهيدريل (sulphhydryl groups).

أما في حالات التسمم المزمن بالزرنيخ فإن الأعراض التي تظهر علي المتسمم تشمل بالإضافة إلي القيء والإسهال المذكورين في الحالات الحادة، وجود هزال شديد وطفح جلدي نزفي مع زيادة في سمك الجلد ولا سيما في راحة اليدين وباطن القدمين (hyperkeratosis) واعتلال عصبي متعدد (polyneuropathy)، ويتم التأكد من الإصابة بقياس مستوى الزرنيخ بالبول حيث يندر أن يتعدى مقداره 0,3 ملليجرام باللتر. ويتم التشخيص بدقة أكثر بقياس محتوى الشعر والأظافر من الزرنيخ.

أما في حالات التسمم بغاز الأرسين فإن الأعراض تظهر على شكل انحلال كريات الدم الحمراء، فيشعر المريض برعشة وبآلام خاصة في موضع الكليتين ويتلون البول بلون قاتم وينشأ عن انحلال الكريات فشل بالكليتين وقد يتضخم الكبد والطحال بحيث يمكن تحسسهما. هذا وقد يتسبب التعرض المزمن للزرنيخ على مدى سنوات طويلة في زيادة الاستعداد لحدوث السرطان وخاصة الجلد ولكن قد ينشأ في أعضاء أخرى.

معالجة التسمم بالزرنيخ: يعتمد العلاج بالإضافة إلى وقف زيادة التعرض للزرنيخ إلى تخليص الجسم من الزرنيخ عن طريق الاستحلاب (chelation) بمادة البال (BAL) أما في حالات التسمم بغاز الأرسين فالمواجهه منع حدوث مزيد من التلف بالكلية حيث يجب عمل غسيل دموي (hemodialysis) وقد يلجأ إلى تبديل الدم (exchange transfusion) بسحب وتعويض المريض بدم حديث.

الباريوم

نسب الباريوم في البيئة من حولنا ضئيلة، ويتواجد في التربة والغذاء مثل المكسرات، أعشاب البحر (الطحالب البحرية)، الأسماك وبعض النباتات. ولا يسبب أضراراً للصحة من الممكن أن نلتفت إليها أو نقف عندها.

من أكثر الأشخاص عرضة لمخاطره العاملين في مجال صناعات الباريوم، وتأتى الأعراض الصحية المرتبطة بهذا المعدن من: الهواء الذى نتنفسه ويحتوى على كبريتات الباريوم أو كربونات الباريوم. بعض أماكن النفايات تحتوى على كميات معينة من الباريوم، والأشخاص التى تعيش بالقرب من هذه النفايات تتعرض لمعدلات من الأضرار الصحية. وهذه الأضرار تأتى من تنفس الهواء المحتوى على الغبار المشبع بمعدن الباريوم أو بأكل الأطعمة التى تزرع في التربة المشبعة به .. أو شرب المياه الملوثة به أيضاً، والتلامس الجلدى عامل آخر من عوامل إصابة الإنسان بمضار الباريوم.

تعتمد درجة الأضرار الصحية من هذا المعدن على قابليته للذوبان، فإذا انحل في الماء كلما كان ضاراً بصحة الإنسان. واستهلاك الكميات الكبيرة منه مع القابلية للذوبان هذه تسبب الشلل وفى بعض الأحيان الموت، أما ذوبان الكميات الضئيلة منه فقد تسبب للشخص صعوبة في التنفس، ارتفاع في ضغط الدم، تغير في معدلات ضربات القلب، وهن في العضلات، تغير في استجابة الأعصاب، تورم الكبد والمخ، ضمور في الكلى والقلب.<

ولم تُظهر نتائج الأبحاث أية نتائج لارتباط إصابة الإنسان بالسرطان عند تعرضه لمعدن الباريوم أو أنه يسبب عقم أو تشوهات للجنين. ولم يتم التوصل إلى أية نتائج بخصوص تسمم الباريوم الناتج من الأطعمة الغذائية.

البيزموث

البيزموث وأملاحه تسبب ضمور في الكلى، على الرغم من أن درجة الضمور هذه عادة لا تكون حادة، لكن الجرعات الكبيرة منه تكون مميتة. ومن الناحية الصناعية، نجد أن البِزموت أحد المعادن الثقيلة التى لها أقل التأثيرات في السُمية.

أما التسمم الخطير منه والذى يودى بحياة الإنسان في بعض الأحيان يأتى من خلال الحقن بجرعات كبيرة منه في تجويفات الجسم المغلقة (عندما يستخدم كدواء، أو من الاستخدام المكثف له والمتزايد على الحروق في شكل مركب محلولى. وقد أثبتت نتائج الأبحاث بضرورة التوقف الفورى عن اللجوء إلى مركبات الباريوم إذا بدأت التهابات اللثة في الظهور لأن هذا ينبؤ باحتمالية إصابة الإنسان بقرحة في المعدة.

ومن الآثار السامة له إحساس بعدم الارتياح، نزول زلال أو مواد بروتينية في البول، الإسهال، اضطرابات في الجلد وفى بعض الأحيان الالتهاب الحاد للطبقة الخارجية للجلد. لا يعتبر البِزموت من العوامل المسببة للسرطان البشرى، كما أن تواجده في الغذاء لا يسبب التسمم.

النحاس الأحمر

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم النحاس

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم النحاس

يتواجد النحاس بشكل طبيعى في البيئة من حولنا. وقد استخدم الإنسان النحاس على نطاق واسع منذ القدم حيث تم تطبيقه في مجال الصناعة والزراعة. وقد تزايد إنتاج النحاس على مر العقود الماضية نتيجة لتوافر كمياته في البيئة. يتواجد النحاس في العديد من الأطعمة، في مياه الشرب وفى الهواء، ولذا فإن جسم الإنسان يمتص هذا المعدن يومياً من خلال الشرب وتناول الأطعمة ومن خلال التنفس أيضاً. هذا الامتصاص هام جداً لصحة الإنسان، وفى نفس الوقت تناول الكميات الكبيرة منه وبتركيزات عالية يكون ضار جداً بصحة الإنسان.

تستقر مركبات النحاس في الماء أو في جزيئات التربة، أما مركباته القابلة للذوبان فمازالت هى التى تشكل الخطر الأعظم لصحة الإنسان. وبداية انتشار مركبات النحاس القابلة للذوبان كانت بعد استخدامه في الزراعة. أما تركيزات معدن النحاس في الهواء تكون عادة بنسب منخفضة، فأضراره التى تلحق بالإنسان من خلال التنفس لا يُلتفت إليها، لكن الأشخاص التى تعيش بالقرب من أماكن صهر المعادن تتعرض لمخاطره.

أما في المنازل التى تكون مواسير المياه فيها مصنعة من النحاس، عند صدأها وتآكلها تبدأ مياه الشرب في التلوث.

تلوث المياه بالنحاس الأحمر ويشمل على تلوث المياه العذبة وتلوث البيئة البحرية: التعرض المهنى لهذا المعدن وارد أيضاً وهذا ما يُعرف (بالحمى المعدنية Metal fever)، حيث تشبه أعراضها الأنفلونزا، وتنتهى أعراض هذه الحالة في خلال يومين وتنتج هذه الحمى نتيجة للحساسية الزائدة من النحاس. التعرض على المد الطويل لمعدن النحاس يسبب تهيج للأنف والفم والعين، كما يسبب الصداع، آلام المعدة، الدوار، القىء، الإسهال.

تناول كميات كبيرة من النحاس عن عمد قد يؤدى إلى ضمور الكلى والكبدومن ثَّم حالات من الوفاة البشرية، أما كونه أحد مسببات السرطان فلم يتم التوصل بعد إلى ذلك. وهناك مقالات علمية تشير إلى الصلة بين التعرض الطويل للتركيزات العالية من النحاس وبين انخفاض القدرة الذكائية لبعض المراهقين الصغار وهذا يدعو إلى أن يكون هناك مزيداُ من البحث والتقصى.

التعرض الصناعى لأدخنة النحاس تؤدى إلى إصابة الإنسان (بحمى الدخان المعدنية Metal fume fever) مع تغير في الأغشية المخاطية للأنف، أما التسمم المزمن منه يصيب الإنسان بمرض ويلسون Wilson disease، وتتمثل أعراضه في التليف الكبدى، تلف خلايا المخ، أمراض الكلى، ترسبات النحاس في القرنية.

الگاليوم

الگاليوم موجود في جسم الإنسان ولكن بكميات ضئيلة، والنسب تمثل بالآتى: إذا كان الشخص يزن 70 كيلوجراماً فإن نسبة الجاليوم الذى يوجد في جسده 0.7 ملجم. ولم يثبت له أية فوائد مرتبطة بوظائف الجسم، ويتواجد من حولنا في البيئة وفى الأطعمة من الخضراوات والفاكهة. والجاليوم النقى ليس مادة ضارة بالإنسان عند التلامس الجلدى معه، بل وقد تم الاستمتاع به عند رؤيته ينصهر بين يدى الإنسان من خلال الحرارة المنبعثة منه، إلا أنه يترك آثاراً من البقع على أيدى الإنسان عند الإمساك به. المركب المشع منه (سترات أو ليمونات الجاليوم) تستخدم في الأغراض الطبية المسح بالجاليوم بدون حدوث أية آثار سلبية منه. على الرغم من أنه غير ضار بكمياته الضئيلة، إلا أنه لا ينبغى اللجوء إلى استهلاكه بجرعات كبيرة. وبعض مركبات الجاليوم ضارة بصحة الإنسان ومنها كلوريد الجاليوم يسبب اهتياج في الحلق، صعوبة في التنفس، آلام في الصدر، أدخنته تسبب أوديما رئوية أو شلل جزئي.

الذهب

الذهب من المعادن الثمينة، ولا توجد له أية آثار سلبية على صحة الإنسان أو سامة ماعدا ردود الفعل من حساسية الجلد.

الهفنيوم

معدن الهفنيوم لا يسبب أية اضطرابات، لكن مركباته يشار إليها على أنها سامة وبالرغم من ذلك فإن عوامل الخطورة محدودة. هذا المعدن غير قابل للذوبان في الماء، أو المحاليل الملحية (السلاين) أو في المواد الكيميائية بالجسد. التعرض لهذا المعدن من خلال التنفس أو التلامس عن طريق العين أو الجلد أو الطعام. التعرض المفرط لمعدن الهفنيوم أو مركباته يسبب استثارة معتدلة للأعين أو الجلد أو الغشاء المخاطى للحيوانات المعملية. لا توجد أية أعراض أو علامات للتعرض المزمن للهفنيوم للإنسان، أو حدوث حالات للتسمم إذا تم تناوله من خلال الأطعمة.

الإنديوم

لا يتعرض غالبية الأشخاص لهذا العنصر الفلزى إلا نادراً جداً، وجميع مكوناته يشار إليها على أنها سامة بدرجة كبيرة حيث تسبب ضمور للقلب والكلى والكبد .. ولا تتوافر معلومات كافية عن الإنديوم وتأثيره على صحة الإنسان لذا فإن اتباع الحذر شيئاً لابد منه. ولا توجد معلومات عن حدوث التسمم بهذا المعدن عند تناول الأطعمة المتواجد فيها لأن تركيزه قليلاً.

الإيريديوم

الإيريديوم هو عنصر فلزى نادر، والجزيئات المتصاعدة في دخان الإيريديوم تسبب استثارة للعين أو للجهاز الهضمى. لا تسبب الأطعمة المحتوية عليه أى درجة من درجات التسمم.

اللنثانوم

اللنثانوم من المعادن النادرة أيضاً، يتواجد في المنازل في الأجهزة التى يعتمد عليها الإنسان مثل التلفزيونات الملونة، مصابيح الفلوروسنت، المصابيح والزجاج الذى يوفر الطاقة. يوجد معدن اللنثانوم في الطبيعة بندرة، ويتزايد مع الأيام الاعتماد على هذا العنصر الفلزى لأنه يستخدم كعامل مساعد في الصناعة ولتلميع الزجاج.

معدن اللنثانوم خطيراً في بيئة العمل لاستنشاق الغازات والأبخرة المشبعة به في الهواء وهذا يسبب الصمامة الرئوية Lung embolism، صمامة الشريان الرئوى هو انسداد مفاجىء للتدفق الدموى في شريان الرئة، وهذا الانسداد قد تسببه التجلطات الدموية، ورم، السائل الأمينوسى، أو دهون في الشريان وخاصة على المدى الطويل بالتعرض له. يسبب معدن اللنثانوم السرطان للإنسان، وخاصة سرطان الرئة عند استنشاقه. يضر بكبد الإنسان عندما يتراكم في الجسم. لم تصل نتائج من دراسات أُجريت عن تعرض الإنسان للإصابة بالتسمم عند تناول الأطعمة المشبعة به.

المنجنيز

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم المنجنيز

مقالة مفصلة: تسمم المنجنيز

المنجنيز هو معدن شائع في استخداماته ومعروف لكثير من الناس، ويوجد في كل مكان على سطح الأرض، ومن المعروف عنه أن بتعرض الإنسان لتركيزات عالية منه يتسبب في إصابته بالتسمم. يتواجد المنجنيز في الأطعمة مثل السبانخ، أما الأطعمة التى تحتوى على أعلى التركيزات من هذا المعدن نجدها في الحبوب، الأرز، الفاصوليا، فول الصويا، المكسرات، زيت الزيتون، الفاصوليا الخضراء، والمحار.

بعدها يمتص جسم الإنسان المنجنيز الذى ينتقل من خلال الدم إلى الكبد والكلى والبنكرياس والغدد الصماء. يؤثر المنجنيز بشكل أساسى على الجهاز التنفسى والمخ. من أعراض التسمم بالمنجنيز: الهلوسة، النسيان، ضمور الأعصاب. كما يسبب المنجنيز الشلل الرعاش، الصمامة الرئوية، التهاب الشعب الهوائية.

عندما يتعرض الإنسان للمنجنيز لفترة طويلة من الزمن قد يؤثر على خصوبته ويسبب له العقم وبعض الاضطرابات الأخرى مثل:

- الشيزوفرنيا

- وهن العضلات

- الصداع

- الأرق

نقص معدلات المنجنيز في جسم الإنسان يعرضه للأضرار الصحية مثل:

- السمنة

- التجلطات الدموية

- اضطرابات الجلد

- معدلات منخفضة من الكوليسترول

- اضطرابات الهيكل العظمى

- تشوهات الجنين الخلقية

- تغير في لون الشعر

- أعراض متصلة بالأعصاب

- حساسية مفرطة من الجلوكوز

التسمم المزمن من المنجنيز يكون نتيجة للاستنشاق طويل المدى لغباره ودخانه. الجهاز العصبى المركزى هو أكثر الأعضاء تأثراً مما ينجم عنه إعاقة دائمة وتتضمن الأعراض على: النوم، الضعف، اضطرابات المشاعر، تكرار الشد العضلى بالرجل، شلل.

وجدت أكبر نسب للإصابة بالالتهاب الرئوى وعدوى الجهاز التنفسى العلوى بين العاملين الذين يتعرضون لأدخنة وغبار مركبات المنجنيز. وثبت أن مركبات المنجنيز (معملياً لكن بشكل غير قاطع) من العوامل التى تساعد على إصابة الإنسان.

النيكل

يوجد النيكل في البيئة بمعدلات قليلة. يستخدم الإنسان معدن النيكل في تطبيقات متعددة، ومن أشهر هذه التطبيقات يستخدم كمكون لمنتجات الصلب والمعادن الأخرى كما نجده في المجوهرات. تحتوى المواد الغذائية على نسب ضئيلة منهن أما من المعروف عن الشيكولاته والدهون أنها تحتوى على كميات عالية من معدن النيكل. تزيد معدلات استهلاكه عند تناول كميات كبيرة من الخضراوات مزروعة في تربة ملوثة به. يتواجد النيكل في المنظفات. المدخن للسجائر يتعرض لتخلل معدن النيكل إلى الرئة. يتعرض الإنسان العادى للنيكل بتنفسه من الهواء وبشربه من مياه الشرب، وتناول الأطعمة أو تدخين السجائر. كما ياتى التعرض بالتلامس الجلدى لتربة أو ماء ملوثتين بهذا المعدن.

تناول الكميات الصغيرة منه ضرورية، أما الكثير منه يعرض الإنسان لمخاطر صحية مثل:

- زيادة مخاطر التعرض لـ: سرطان الرئة، سرطان الأنف، سرطان

الحنجرة، سرطان البروستاتة * الشعور بالدوار والإعياء بعد التعرض لغازات النيكل.

- الإصابة بالصمامة الرئوية.

- فشل الجهاز التنفسى.

- التشوهات الخلقية للجنين.

- أزمة الربو، التهاب الشعب الهوائية.

- اضطرابات في القلب.

- ردود فعل من الحساسية مثل الطفح الجلدى وخاصة عند ارتداء المجوهرات.

- أدخنة النيكل من مثيرات الجهاز التنفسى وقد تسبب الالتهاب الرئوى.

- التعرض للنيكل ومركباته قد ينتج عنها التهاب طبقة الجلد الخارجية والمعروف عنها باسم (هرش النيكل - Nickel Itch) للأشخاص الذى يكون جلدها حساس أو لديها حساسية من النيكل.

تم تصنيف النيكل طبقاً للوكالة الدولية لأبحاث السرطان في مجموعتين:

- المجموعة (أ): مركبات النيكل مسببة للسرطان في الإنسان، وهناك أدلة كافية تثبت ذلك.

- المجموعة (ب): تصنف النيكل نفسه بأنه إحدى العوامل المحتمل أن تساهم في إصابة الإنسان بالسرطان.

النيوبيوم

يُستخدم معدن النيوبيوم مع الأستنلس ستيل في الطائرات النفاثة، الصواريخ، أدوات التقطيع، مواسير المياه، قضيب اللحام، المغناطيس، المفاعلات النووية. عند استنشاق النيوبيوم يستقر في الرئة أولاً ثم في العظام. ويتداخل مفعوله مع الكالسيوم كمنشط لنظام الإنزيمات. لا توجد هناك معلومات بخصوص إصابة الإنسان بالتسمم من النيوبيوم من الأطعمة لأن تركيزاته في المواد الغذائية منخفضة للغاية.

الپلاديوم

من النادر تعامل الإنسان مع هذا المعدن، وكل مركبات الپلاديوم بها درجة سُمية عالية، كما أنها تسبب السرطانات. كلوريد البلاديوم ضار جداً بالصحة وسام إذا بلعه الإنسان أو إذا تم استنشاقه أو امتصاصه عن طريق الجلد. ومن خلال إجراء التجارب المعملية على الحيوانات ثبت تأثيره السيىء على نخاع العظام والكبد والكلى. وعلى الرغم من ذلك، كان يُوصف كلوريد البلاديوم سابقاً لعلاج السعال الديكى، بجرعة 0.065 جرام/اليوم (حوالى 1 ملجم/كجم) وكانت لا توجد له آثار جانبية كثيرة. لا توجد معلومات عن إصابة الإنسان بالتسمم منه من خلال الأطعمة لأن تركيزاته تكون قليلة للغاية.

الپلاتين

تركيزات الپلاتين في التربة والماء والهواء ضئيلة، وفى بعض الأماكن نجد أن الترسبات بفعل العمليات الطبيعية تكون غنية بمحتواها من البلاتنيوم وخاصة في جنوب أفريقيا وروسيا والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. يستخدم البلاتنيوم كمكون لمنتجات معدنية عديدة مثل الإلكترود، وكعامل مساعد في العديد من التفاعلات الكيميائية. تستخدم مركبات البلاتنيوم كنوع من أنواع العقاقير لعلاج السرطان.

والبلاتنيوم كمعدن ليس خطيراً، لكن مع أملاح البلاتنيوم يكون التأثير الضار لهذا المعدن ومنها:

- تغير في الصفات الوراثية.

- السرطان.

- عند التعرض لها يصاب بعض الأشخاص بحساسية في الجلد أو الأغشية المخاطية.

- ضمور في بعض الأعضاء مثل الأمعاء الدقيقة، الكلى، نخاع العظام.

- ضمور الأعصاب السمعية.

- عند استخدام أملاح البلاتنيوم فهناك احتمالية بزيادة خطورة بعض المواد الكيميائية الأخرى في جسم الإنسان مثل السيلنيوم.

- لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير بحدوث تسمم البلاتنيوم من الأطعمة.

الروديوم

يستخدم الروديوم فقط في الصناعات الكيميائية، وكافة مركبات معدن الروديوم تسبب التسمم والسرطان. كما أنها تترك آثاراً من البقع قوية على الجلد. لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث تسمم الروديوم من الأطعمة لأن تركيزاته ضئيلة.

الروثنيوم

معدن الروثنيوم استخداماته نادرة أيضاً مثل العديد من المعادن السابقة وكافة مركباته تسبب التسمم والسرطان وتترك آثاراً من البقع قوية على الجلد. الروثينيوم في الأطعمة يتبقى في العظام، كما أن أكسيد الروثينيوم درجة سُميته عالية ومتطاير لذا ينبغى تجنبه. لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث تسمم الروثينيوم من الأطعمة لأن تركيزاته ضئيلة.

الإسكنديوم

الإسكنديوم من المعادن النادرة، ونجده متمثلاً في الأجهزة المنزلية مثل التلفزيونات الملونة، المصابيح الفلوروسنت، الزجاج والمصابيح التى توفر الطاقة. يتواجد الإسكنديوم في الطبيعة ولكن بكميات ضئيلة، يوجد في نوعين مختلفين فقط. مازالت استخداماته في تطور مستمر مثل تلميع الزجاج. يعتبر الإسكنديوم من المعادن الخطيرة في بيئة العمل للأدخنة المتصاعدة منه في الهواء مسبباً الصمامة الرئوية وخاصة عند التعرض على المدى الطويل له. يهدد الإسكنديوم الكبد إذا تراكم في جسم الإنسان.

الفضة

الفضة معدن غير ضار، كما تستخدم في إضافة الألوان للأطعمة أملاح الفضة القابلة للذوبان وخاصة (AgNo3) مميتة للبالغين بتركيز 2 جرام، ومركبات الفضة تقوم أنسجة الجسم بامتصاصها ببطء وتسبب تغير في صبغة الجلد إلى اللون المائل للزرقة أو السواد وهو ما يسمى بتسمم الفضة Argyria. الاتصال المتكرر على المدى الطويل بالفضة يسبب الحساسية. أما التعرض للأبخرة المتصاعدة منها يسبب دوار، صعوبة في التنفس، صداع، اهتياج الجهاز التنفسى.< التركيزات العالية من الفضة من الممكن أن تسبب للإنسان إحساس بالنعاس، عدم تركيز، فقد الوعى، الغيبوبة أو الموت.

الفضة في حالتها السائلة أو مع الأبخرة المتصاعدة منها تسبب تهيج للجلد وللعين والحلق والرئة. الاستخدام السيىء لها عن عمد مثل استنشاق أبخرتها لا يقف عند حد الضرر وإنما الموت أيضاً. قد تسبب اضطرابات في المعدة وشعور بعدم الارتياح، الغثيان، القىء، الإسهال. إذا تم استنشاق المادة ووصولها للرئة أو تم ابتلاعها أو حدث تقيؤ فكل هذه أعراض منذرة بالإصابة بالالتهاب الرئوى الكيميائى وتسبب موت الإنسان في النهاية. لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث تسمم الفضة من الأطعمة لأن تركيزاتها ضئيلة للغاية.

السترونشيوم

مركبات السترونشيوم غير القابلة للذوبان من الممكن أن تتحول لتصبح قابلة للذوبان نتيجة التفاعلات الكيميائية. وعن المركبات القابلة للذوبان فهى خطر حقيقى يهدد حياة الإنسان بخلاف تلك غير القابلة للذوبان، ولذلك فإن المركبات القابلة للذوبان في الماء تلوث مياه الشرب. ولحسن الحظ أن تركيزات هذه المركبات في المياه نسبها ضئيلة للغاية. قد يتعرض الأشخاص أيضاً إلى معدلات صغيرة من الأسترنتيوم الإشعاعى من خلال تنفسه في الهواء، بتناول الأطعمة، شرب المياه، أو بالتلامس مع التربة التى تحتوى عليه.

ومن تلك الأطعمة التى تحتوى على معدن الأسترنتيوم بنسب عالية الحبوب، الخضراوات الورقية، ومنتجات الألبان. المعدلات المتوسطة من تناوله لا تسبب أية أضرار صحية، والمركب الوحيد الذى يمثل خطورة على صحة الإنسان حتى وإن كان استخدامه بكميات ضئيلة هو كرومات الأسترنتيوم حيث تسبب سرطان الرئة. استهلاكه لا يسبب أية مخاطر صحية للإنسان، أما الاضطرابات المحتمل تعرض الإنسان لها: * حساسية لكنه لا توجد حالات فعلية.

- إفراط الأطفال في تناول الأسترنتيوم

- يسبب مشاكل في نمو العظام. ليست هناك نتائج عما تسببه أملاح الأسترنتيوم من اضطرابات للجلد من أى نوع.

التنتالوم

التنتالوم قد يكون ضاراً عند استنشاقه، تناوله في الأطعمة، أو امتصاصه عن طريق الجلد حيث يسبب اهتياج للجلد والعين بالمثل. مادة التنتالوم تسبب استثارة للأغشية المخاطية والجهاز التنفسى العلوى. ومن خلال التجارب المعملية وحقن الفئران بجرعات كبيرة من هذا المعدن، ثبت ما يحدثه من تلف لأنسجة الجهاز التنفسى. لا توجد هناك أية علامات أو أعراض ظهرت على الإنسان مع التعرض المزمن له. كما أنه لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث تسمم التنتالوم من الأطعمة.

الثاليوم

يوجد معدن الثاليوم في الطبيعة بكميات ضئيلة، ولا يستخدم من قبل الإنسان على نطاق واسع. لكن قابلية جسم الإنسان لامتصاصه سهلة للغاية وخاصة من خلال الجلد أو عن طريق أعضاء الجهاز التنفسى أو الهضمى. والتسمم بمعدن الثاليوم يكون وراءه سم الفئران إذا تم أخذه بطريق الخطأ حيث يحتوى على كميات كبيرة من كبريتات الثاليوم والتى تترجم أعراضه إلى: آلام بالمعدة، ضمور في الجهاز العصبى، وفى بعض الحالات لا يمكن تقديم العلاج ويتوفى الإنسان بعد ظهور أعراض التسمم.

أما أعراض الجهاز العصبى فتتمثل فى:

- الارتعاش.

- الشلل.

- التغيرات السلوكية والتى تلازم الإنسان وتبقى معه بعد الإصابة.

أما التسمم بالثاليوم للأجنة يصل ضرره للتشوهات الخلقية.

تراكم معدن الثاليوم في جسم الإنسان له تأثير مزمن معروف: الشعور بالإرهاق والتعب، الصداع، الاكتئاب، فقدان الشهية، آلام الرجل، تساقط الشعر، اضطرابات الرؤية.

وعن الآثار الأخرى المرتبطة بالتسمم الناتج عن الثاليوم هى آلام الأعصاب والمفاصل.

وكل الأعراض السابقة قد ترتبط بتناول الأطعمة الغذائية الغنية به، وفى الوقت ذاته فإن حالات التسمم المرتبطة بالأطعمة نادرة الحدوث ويكون سببها التلوث البيئى أيضاً.

التنجستين

يقاوم معدن التنجستين معدن المولبدينيوم استنشاق هذا المعدن يسبب استثارة للرئة والغشاء المخاطى. استثارة العين يسفر عنها احمرار ودموع.التهاب الجلد: الاحمرار والهرش ووجود الندبات.التعرض المتكرر أو على المدى الطويل: لا يوجد هناك ما يفيد تدهور أياً من الحالات الطبية المرضية. لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث تسمم التنجستين من الأطعمة.

الڤاناديوم

الڤاناديوم هو معدن متواجد في الأطعمة الغذائية مثل فول الصويا، زيت الزيتون، زيت عباد الشمس، التفاح، البيض. هذا المعدن له تأثير سلبى على صحة الإنسان إذا تعرض له بتركيزات عالية، فاستنشاقه في الهواء يسبب التهاب الشعب الهوائية والالتهاب الرئوى. التأثيرات الحادة له متمثلة في اهتياج الرئة والحلق والعين والتجاويف الأنفية.

أما الأعراض الصحية الأخرى:

- أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية.

- التهاب المعدة والأمعاء.

- ضمور الجهاز العصبى.

- نزيف الكلى والكبد.

- طفح جلدى.

- رجفة حادة وشلل.

- آلام الحلق.

- نزيف من الأنف.

- ضعف.

- شعور بالإعياء.

- صداع.

- دوار.

- تغيرات سلوكية.

والمخاطر الصحية التى يتعرض لها الإنسان مع هذا المعدن تعتمد على حالة التأكسد التى يوجد عليها. الفاناديوم في صورته الخام من الممكن أن يتأكسد ليتحول إلى "أكسيد الفاناديوم الخماسى - Vanadium pentoxide" خلال عملية اللحام وهذا النوع المتأكسد يكون أكثر خطورة من النوع الخام.

التعرض المزمن لأدخنة الفاناديوم وغباره يسبب استثارة للعين والجلد والجهاز التنفسى العلوى، الالتهاب مستمر للقصبة والشعب الهوائية، تكون الأوديما الرئوية والتسمم.

الإتريوم

الإتريوم هو من العناصر الفلزية النادرة، ويتواجد في الأجهزة المنزلية مثل أجهزة التلفزيون الملونة، مصابيح الفلوروسنت، الزجاج والمصابيح التى توفر الطاقة. معدن الإيثريوم متواجد بندرة في الطبيعة وبكميات ضئيلة، ويتألف من نوعين مختلفين وما زالت استخداماته في طور النمو. من المعادن الخطيرة في بيئة العمل للأبخرة المتصاعدة منه في الهواء. يسبب معدن الإيثريوم الصمامة الرئوية، وخاصة مع التعرض على المدى الطويل له. يسبب الإيثريوم مرض السرطان وخاصة سرطان الرئة. يهدد الإيثريوم الكبد إذا تراكم هذا المعدن في جسم الإنسان. لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث التسمم من الأطعمة التى تحتوى على معدن الإيثريوم.

الزركونيوم

معدن الزركونيوم وأملاحه به نسبة سُمية ضئيلة، لا توجد هناك أية نتائج تشير إلى حدوث حالات تسمم الزركونيوم من الأطعمة لوجوده بتركيزات ضئيلة في المواد الغذائية.

العلاج

قد يشمل علاج التسمم بالفلزات الثيقة التدخل الطبي الفوري لكونها حالة طارئة لتجنب التلف الدائم للجهاز العصبي والقناة الهضمية وتتمثل بازالة المعدن الثيقل عن طريق الفم، الوريد أو العضل ويرتبط بدوره بالمعدن الثيقل في أنسجة الجسم المختلفة ومن ثم يُطرح إلى خارج الجسم عن طريق البول. في الحالات المتوسطة من التسمم بالزرنيخ، الثاليوم أو الزئبق يُحفز التقيؤ باعطاء الفحم النشط ومن ثم اجراء غسيل للمعدة.

الوقاية

يُوصى بضرورة ارتداء الأقنعة والملابس الواقية لتجنب التعرض السُمي للفلزات الثقيلة في موقع العمل وعدم ارتداء الملابس ذاتها في المنزل.

الفوائد

الكائنات الحية تحتاج إلى كميات مختلفة من "المعادن الثقيلة"، مثل الحديد والكوبالت والنحاس والمنگنيز والموليبدينوم، والزنك والسيلنيوم، حيث يكون استهلاك هذه المعادن ضروريا وهاما للمحافظة على عملية التمثيل الغذائي (الآيض) بجسم الكائن الحي. ولكن استهلاك كميات كبيرة منها (التركيزات العالية) يكون ضاراً بل وساماً وينتج عنه ما يُسمى بـتسمم المعادن الثقيلة.

تشكل المعادن نسبة 45 من وزن جسم الإنسان، ويتركز معظمها في الهيكل العظمي. وتأتي خطورة المعادن الثقيلة من تراكمها الحيوي داخل جسم الإنسان بشكل أسرع من انحلالها من خلال عملية التمثيل الغذائي (الآيض) أو إخراجها.

انظر أيضاً

- إزالة سموم الفلزات الثقيلة

- تسرب طمي غبار الفحم المتطاير من محطة كينگستون للوقود الأحفوري

- فلز خفيف

- الفلزات الثقيلة السامة

الهوامش

- ^ Criteria used were density:[6] (1) above 3.5 g/cm3; (2) above 7 g/cm3; atomic weight: (3) > 22.98;[6] (4) > 40 (excluding s- and f-block metals);[7] (5) > 200;[8] atomic number: (6) > 20; (7) 21–92;[9] chemical behaviour: (8) United States Pharmacopeia;[10][11][12] (9) Hawkes' periodic table-based definition (excluding the lanthanides and actinides);[13] and (10) Nieboer and Richardson's biochemical classifications.[14] Densities of the elements are mainly from Emsley.[15] Predicted densities have been used for At, Fr and elements 100–117.[16] Indicative densities were derived for Fm, Md, No and Lr based on their atomic weights, estimated metallic radii,[17] and predicted close-packed crystalline structures.[18] Atomic weights are from Emsley.,[15] inside back cover

- ^ Metalloids were, however, excluded from Hawkes' periodic table-based definition given he noted it was "not necessary to decide whether semimetals [i.e. metalloids] should be included as heavy metals."[13]

- ^ Lead, which is a cumulative poison, has a relatively high abundance due to its extensive historical use and human-caused discharge into the environment.[37]

- ^ Haynes shows an amount of < 17 mg for tin[38]

- ^ Iyengar records a figure of 5 mg for nickel;[39] Haynes shows an amount of 10 mg[38]

- ^ Encompassing 45 heavy metals occurring in quantities of less than 10 mg each, including As (7 mg), Mo (5), Co (1.5), and Cr (1.4)[40]

- ^ Trace elements having an abundance much less than the one part per trillion of Ra and Pa (namely Tc, Pm, Po, At, Ac, Np, and Pu) are not shown. Abundances are from Lide[41] and Emsley;[42] occurrence types are from McQueen.[43]

- ^ Sulfides of the Group 1 and 2 metals, and aluminium, are hydrolysed by water;[54] scandium,[55] yttrium[56] and titanium sulfides[57] are insoluble.

- ^ For example, the hydroxides of potassium, rubidium, and caesium have solubilities exceeding 100 grams per 100 grams of water[59] whereas those of aluminium (0.0001)[60] and scandium (<0.000 000 15 grams)[61] are regarded as being insoluble.

- ^ Beryllium has what is described as a "high" melting point of 1560 K; scandium and titanium melt at 1814 and 1941 K.[66]

- ^ Zinc is a soft metal with a Moh's hardness of 2.5;[67] cadmium and lead have lower hardness ratings of 2.0 and 1.5.[68] Zinc has a "low" melting point of 693 K; cadmium and lead melt at 595 and 601 K.[69]

- ^ Some violence and abstraction of detail was applied to the sorting scheme in order to keep the number of categories to a manageable level.

- ^ The skin has largely turned green due to the formation of a protective patina composed of antlerite Cu3(OH)4SO4, atacamite Cu4(OH)6Cl2, brochantite Cu4(OH)6SO4, cuprous oxide Cu2O, and tenorite CuO.[105]

- ^ For the lanthanides, this is their only structural use as they are otherwise too reactive, relatively expensive, and moderately strong at best.[117]

- ^ Weller[119] classifies coinage metals as precious metals (e.g., silver, gold, platinum); heavy metals of very high durability (nickel); heavy metals of low durability (copper, iron, zinc, tin, and lead); and light metals (aluminium).

- ^ Emsley[120] estimates a global loss of six tonnes of gold a year due to 18-carat wedding rings slowly wearing away.

- ^ Sheet lead exposed to the rigours of industrial and coastal climates will last for centuries[83]

- ^ Electrons impacting the tungsten anode generate X-rays;[153] rhenium gives tungsten better resistance to thermal shock;[154] molybdenum and graphite act as heat sinks. Molybdenum also has a density nearly half that of tungsten thereby reducing the weight of the anode.[152]

الحواشي

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 288; 374

- ^ : التقرير التقني للإتحاد الدولي للكمياء البحتة والتطبيقية IUPAC.

- ^ Dewan 2008

- ^ Dewan 2009

- ^ Poovey 2001

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDuffus798 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRand - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBaldwin - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLyman - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSP - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRaghuram - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةThorne - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHawkes - ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, p. 4

- ^ أ ب Emsley 2011

- ^ Hoffman, Lee & Pershina 2011, pp. 1691,1723; Bonchev & Kamenska 1981, p. 1182

- ^ Silva 2010, pp. 1628, 1635, 1639, 1644

- ^ Fournier 1976, p. 243

- ^ أ ب ت Vernon 2013, p. 1703

- ^ Järup & 2003, p. 168; Rasic-Milutinovic & Jovanovic 2013, p. 6; Wijayawardena, Megharaj & Naidu 2016, p. 176

- ^ Duffus 2002, pp. 794–795; 800

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 480

- ^ USEPA 1988, p. 1; Uden 2005, pp. 347–348; DeZuane 1997, p. 93; Dev 2008, pp. 2–3

- ^ أ ب Ikehata et al. 2015, p. 143

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 71

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 30

- ^ أ ب Podsiki 2008, p. 1

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 106

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 62

- ^ Chakhmouradian, Smith & Kynicky 2015, pp. 456–457

- ^ Cotton 1997, p. ix; Ryan 2012, p. 369

- ^ Hermann, Hoffmann & Ashcroft 2013, p. 11604-1

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 75

- ^ Gribbon 2016, p. x

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 428–429; 414; Wiberg 2001, pp. 527; Emsley 2011, pp. 437; 21–22; 346–347; 408–409

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 35; passim

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 280, 286; Baird & Cann 2012, pp. 549, 551

- ^ أ ب Haynes 2015, pp. 7–48

- ^ Iyengar 1998, p. 553

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 47; 331; 138; 133; passim

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLide - ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 29; passim

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMcQueen - ^ Cox 1997, pp. 73–89

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, p. 437

- ^ McCurdy 1992, p. 186

- ^ von Zeerleder 1949, p. 68

- ^ Chawla & Chawla 2013, p. 55

- ^ von Gleich 2006, p. 3

- ^ Biddle & Bush 1949, p. 180

- ^ Magill 1992, p. 1380

- ^ أ ب Gidding 1973, pp. 335–336

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTMS - ^ Wiberg 2001, p. 520

- ^ أ ب Schweitzer & Pesterfield 2010, p. 230

- ^ Macintyre 1994, p. 334

- ^ Booth 1957, p. 85; Haynes 2015, pp. 4–96

- ^ Schweitzer & Pesterfield 2010, p. 230. The authors note, however, that, "The sulfides of ... Ga(III) and Cr(III) tend to dissolve and/or decompose in water."

- ^ Sidgwick 1950, p. 96

- ^ Ondreička , Kortus & Ginter 1971, p. 294

- ^ Gschneidner 1975, p. 195

- ^ Hasan 1996, p. 251

- ^ Brady & Holum 1995, p. 825

- ^ Cotton 2006, pp. 66; Ahrland, Liljenzin & Rydberg 1973, p. 478

- ^ Nieboer & Richardson 1980, p. 10

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 158, 434, 180

- ^ Schweitzer 2003, p. 603

- ^ Samsonov 1968, p. 432

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 338–339; 338; 411

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlongo - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHerron - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNathans - ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 260; 401

- ^ Jones 2001, p. 3

- ^ Berea, Rodriguez-lbelo & Navarro 2016, p. 203

- ^ Alves, Berutti & Sánchez 2012, p. 94

- ^ Yadav, Antony & Subba Reddy 2012, p. 231

- ^ Masters 1981, p. 5

- ^ Wulfsberg 1987, pp. 200–201

- ^ Bryson & Hammond 2005, p. 120 (high electron density); Frommer & Stabulas-Savage 2014, pp. 69–70 (high atomic number)

- ^ Landis, Sofield & Yu 2011, p. 269

- ^ Prieto 2011, p. 10; Pickering 1991, pp. 5–6, 17

- ^ أ ب Emsley 2011, p. 286

- ^ Berger & Bruning 1979, p. 173

- ^ Jackson & Summitt 2006, pp. 10, 13

- ^ Shedd 2002, p. 80.5; Kantra 2001, p. 10

- ^ Spolek 2007, p. 239

- ^ White 2010, p. 139

- ^ Dapena & Teves 1982, p. 78

- ^ Burkett 2010, p. 80

- ^ أ ب Moore & Ramamoorthy 1984, p. 102

- ^ أ ب National Materials Advisory Board 1973, p. 58

- ^ Livesey 2012, p. 57

- ^ VanGelder 2014, pp. 354, 801

- ^ National Materials Advisory Board 1971, pp. 35–37

- ^ Frick 2000, p. 342

- ^ Rockhoff 2012, p. 314

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 16, 96

- ^ Morstein 2005, p. 129

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 218–219

- ^ Lach et al. 2015; Di Maio 2016, p. 154

- ^ Preschel 2005; Guandalini et al. 2011, p. 488

- ^ Scoullos et al. 2001, p. 315; Ariel, Barta & Brandon 1973, p. 126

- ^ Wingerson 1986, p. 35

- ^ Matyi & Baboian 1986, p. 299; Livingston 1991, pp. 1401, 1407

- ^ Casey 1993, p. 156

- ^ أ ب ت Bradl 2005, p. 25

- ^ Kumar, Srivastava & Srivastava 1994, p. 259

- ^ Nzierżanowski & Gawroński 2012, p. 42

- ^ Pacheco-Torgal, Jalali & Fucic 2012, pp. 283–294; 297–333

- ^ Venner et al. 2004, p. 124

- ^ Technical Publications 1958, p. 235: "Here is a rugged hard metal cutter ... for cutting ... through ... padlocks, steel grilles and other heavy metals."

- ^ Naja & Volesky 2009, p. 41

- ^ Department of the Navy 2009, pp. 3.3–13

- ^ Rebhandl et al. 2007, p. 1729

- ^ Greenberg & Patterson 2008, p. 239

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 437, 441

- ^ Roe & Roe 1992

- ^ Weller 1976, p. 4

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 208

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 206

- ^ Guney & Zagury 2012, p. 1238; Cui et al. 2015, p. 77

- ^ Brephol & McCreight 2001, p. 15

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, pp. 337, 404, 411

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 141; 286

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 625

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 555, 557

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 531

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 123

- ^ Weber & Rutula 2001, p. 415

- ^ Dunn 2009; Bonetti et al. 2009, pp. 1, 84, 201

- ^ Desoize 2004, p. 1529

- ^ Atlas 1986, p. 359; Lima et al. 2013, p. 1

- ^ Volesky 1990, p. 174

- ^ Nakbanpote, Meesungnoen & Prasad 2016, p. 180

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 447; 74; 384; 123

- ^ Elliot 1946, p. 11; Warth 1956, p. 571

- ^ McColm 1994, p. 215

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 135; 313; 141; 495; 626; 479; 630; 334; 495; 556; 424; 339; 169; 571; 252; 205; 286; 599

- ^ Everts 2016

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 450

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 334

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 459

- ^ Moselle 2004, pp. 409–410

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, p. 323

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 212

- ^ Tretkoff 2006

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 428; 276; 326–327

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 73; 141; 141; 141; 355; 73; 424; 340; 189; 189

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 192; 242; 194

- ^ Baranoff 2015, p. 80; Wong et al. 2015, p. 6535

- ^ أ ب Ball, Moore & Turner 2008, p. 177

- ^ Ball, Moore & Turner 2008, pp. 248–249, 255

- ^ Russell & Lee 2005, p. 238

- ^ Tisza 2001, p. 73

- ^ Chandler & Roberson 2009, pp. 47, 367–369, 373; Ismail, Khulbe & Matsuura 2015, p. 302

- ^ Ebbing & Gammon 2017, p. 695

- ^ Pan & Dai 2015, p. 69

- ^ Brown 1987, p. 48

- ^ Wright 2002, p. 288

- ^ التسمم بالفلزات الثقيلة، الطبي.كوم

- ^ المعادن الثقيلة.. سموم بيئية، فيدو

- ^ Clifton JC 2nd (2007). "Mercury exposure and public health". Pediatr Clin North Am. 54 (2): 237–69, viii. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.02.005. PMID 17448359.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bjørklund G (1995). "Mercury and Acrodynia" (PDF). Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 10 (3 & 4): 145–146.

- ^ Davidson PW, Myers GJ, Weiss B (2004). "Mercury exposure and child development outcomes". Pediatrics. 113 (4 Suppl): 1023–9. doi:10.1542/peds.113.4.S1.1023. PMID 15060195.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cs uros 1997, p. 124

المصادر

- Afal A & Wiener SW 2014, Metal Toxicity, Medscape.org, viewed 21 April 2014

- American Cancer Society 2008, Chelation Therapy, viewed 28 April 2014

- Balasubramanian R, He J & Wang LK 2009, 'Control, Management, and Treatment of Metal Emissions from Motor Vehicles', in LK Wang, JP Chen, Y Hung & NK Shammas (eds), Heavy Metals in the Environment, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 475–490, ISBN 1420073168

- Bánfalvi G 2011, 'Heavy Metals, Trace Elements and their Cellular Effects', in G Bánfalvi (ed.), Cellular Effects of Heavy Metals, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 3–28, ISBN 9789400704275

- Barceloux DG & Barceloux D 1999, 'Chromium', Clinical Toxicology, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 173–94, DOI:10.1081/CLT-100102418

- Blake J 1884, 'On the Connection Between Physiological Action and Chemical Constitution', The Journal of Physiology, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 36–44.

- Blannn A & Ahmed N 2014, Blood science: Principles and pathology, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, West Sussex, ISBN 9781118351468

- Cameron CA 1871, 'Half-yearly Report on Public Health', Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medical Science, vol. 52, May 1, pp. 475–498

- Chowdhury BA & Chandra RK 1987, 'Biological and Health Implications of Toxic Heavy Metal and Essential Trace Element Interactions', Progress in Food & Nutrition Science, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 55–113

- Cooper RG & Harrison AP 2009, 'The uses and adverse effects of beryllium on health', Indian Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 65–76, DOI:10.4103/0019-5278.55122

- Csuros M 1997, Environmental Sampling and Analysis Lab Manual, Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL, ISBN 1566701783

- Davidson PW, Myers GJ & Weiss B 2004, 'Mercury Exposure and Child Development Outcomes', Pediatrics, vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 1023–9

- Dewan S 2008, 'Tennessee Ash Flood Larger Than Initial Estimate', New York Times, 26 December, viewed 18 May 2014

- Dewan S 2009, 'Metal Levels Found High in Tributary After Spill', New York Times, 1 January, viewed 18 May 2014

- Di Maio VJM 2001, Forensic Pathology, 2nd ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, ISBN 084930072X

- Dueck D 2000, Strabo of Amasia: A Greek Man of Letters in Augustan Rome, Routledge, London, ISBN 0415216729

- Duffus JH 2002, '"Heavy Metals"—A Meaningless Term?', Pure and Applied Chemistry, vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 793–807

- Dyer P 2009, 'The 1900 Arsenic Poisoning Epidemic,' Brewery History, no. 130, pp. 65–85

- Emsley J 2011, Nature's Building Blocks, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 9780199605637

- Evanko CA & Dzombak DA 1997, Remediation of Metals-Contaminated Soils and Groundwater, Technology Evaluation Report, TE 97-0-1, Ground-water Remediation Technologies Center, Pittsburgh, PA

- Gmelin L 1849, Hand-Book of Chemistry, vol. III, Metals, translated from the German by H Watts, Cavendish Society, London

- Gilbert SG & Weiss B 2006, 'A Rationale for Lowering the Blood Lead Action Level from 10 to 2 μg/dL', Neurotoxicology, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 693–701, DOI:10.1016/j.neuro.2006.06.008

- Habashi F 2009, 'Gmelin and his Handbuch', Bulletin for the History of Chemistry, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 30–1

- Haines AT & Nieboer E 1988, 'Chromium hypersensitivity', in JO Nriagu & E Nieboer (eds), Chromium in the Natural and Human Environments, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 497–532, ISBN 0471856436

- Hawkes SJ 1997, 'What is a "Heavy Metal"?', Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 74, no. 11, p. 1374

- Houlton S 2014, 'Boom!', Chemistry World, vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 48–51

- Jones J 2011, 'Stockton Residents Fume Over Fallout From Orica', Newcastle Herald, 11 August, viewed 16 May 2014

- Landis WG, Sofield RM & Yu M-H 2000, Introduction to Environmental Toxicology: Molecular Substructures to Ecological Landscapes, 4th ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 9781439804100

- Lovei M 1998, Phasing Out Lead from Gasoline: Worldwide Experience and Policy Implications, World Bank Technical Paper No. 397, The World Bank, Washington, DC, ISSN 0253-7494

- Kumar V, Abbas AK & Aster JC 2013, 'Environmental and nutritional diseases,' in V Kumar, AK Abbas & JC Aster (eds), Robbins Basic Pathology, 9th ed., Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5

- Mulvihill G & Pritchard J 2010, 'McDonald's Recall: 'Shrek' Glasses Contain Toxic Metal Cadmium', Huffington Post, 4 June, viewed 24 April 2014

- National Capital Poison Center, "Chelation: Therapy or "Therapy"?", viewed 28 April 2014

- National Research Council, Committee on Biologic Effects of Atmospheric Pollutants 1974, Chromium, National Academy of Sciences, Washington

- Needleman H 2004, 'Lead poisoning', Annual Review of Medicine, vol. 55, pp. 209–22 DOI:10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103653

- New Scientist 2014, 'Rogue mercury', vol. 223, no. 2981

- Nielen MWF & Marvin HJP 2008, 'Challenges in Chemical Food Contaminants and Residue Analysis', in Y Picó (ed.), Food Contaminants and Residue Analysis, Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, vol. 51, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 1–28, ISBN 0080931928

- Newman D 1890, 'A Case of Adeno-carcinoma of the Left Inferior Turbinated Body, and Perforation of the Nasal Septum, in the Person of a Worker in Chrome Pigments', The Glasgow Medical Journal, vol. 33, pp. 469–470

- Newman MC & Unger MA 2003, Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology, 2nd ed., Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL, ISBN 1566705983

- Notman N 2014, 'Digging Deep for Safer Water', Chemistry World, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 54–57

- O'Brien N & Aston H 2011, 'The untold story of Orica's chemical leaks', Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November, viewed 16 May 2014

- Park CC 2013, Acid Rain: Rhetoric and Reality, Routledge, Abingdon, ISBN 9780415712767

- Pearce JM 2007, 'Burton's Line in Lead Poisoning', European Neurology, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 118–9, DOI:10.1159/000098100

- Perry J & Vanderklein EL 1996, Water Quality: Management of a Natural Resource, Blackwell Science, Cambridge, ISBN 0865424691

- Pezzarossa B, Gorini F & Petruzelli G 2011, 'Heavy Metal and Selenium Distribution and Bioavailability in Contaminated Sites: A Tool for Phytoremediation', in HM Selim, Dynamics and Bioavailabiliy of Heavy Metals in the Rootzone, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 93–128, ISBN 9781439826225

- Poovey B 2001, 'Trial Starts on Damage Lawsuits in TVA Ash Spill', Bloomberg Businessweek, 15 September, viewed 18 May 2014

- Prioreschi P 1998, A History of Medicine: Vol. III—Roman Medicine, Horatius Press, Omaha, NE, ISBN ISBN 1888456035

- Pritchard J 2010, 'Wal-Mart Pulls Miley Cyrus Jewelry After Cadmium Tests', USA Today, May 19, viewed 24 April 2014

- Qu C, Ma Z, Yang J, Lie Y, Bi J & Huang L 2014, 'Human Exposure Pathways of Heavy Metal in a Lead-Zinc Mining Area', in E Asrari (ed.), Heavy Metal Contamination of Water and Soil: Analysis, assessment, and remediation strategies, Apple Academic Press, Oakville, Ontario, pp. 129–156, ISBN 9781771880046

- Radojevic M & Bashkin VN 1999, Practical Environmental Analysis, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, ISBN 0854045945

- Rand GM, Wells PG & McCarty LS 1995, 'Introduction to aquatic toxicology', in GM Rand (ed.), Fundamentals Of Aquatic Toxicology: Effects, Environmental Fate And Risk Assessment, 2nd ed., Taylor & Francis, London, pp. 3–70, ISBN 1560320907

- Rogers MJ 2000, 'Text and Illustrations. Dioscorides and the Illuminated Herbal in the Arab Tradition', In A Contadini (ed.), Arab Painting: Text and Image in Illustrated Arabic Manuscripts, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, pp. 41–48 (41), ISBN 9789004186309

- Saxena P & Misra N 2010, 'Remediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Tropical Land' in I Sherameti & A Varma, Soil Heavy Metals, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 431–78, ISBN 9783642024351

- Sengupta AK 2002, 'Principles of Heavy Metals Separation', in AK Sengupta (ed.), Environmental Separation of Heavy Metals: Engineering Processes, Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL, ISBN 1566768845

- Tovey J 2011, 'Patches of Carcinogen Seen After Orica Leak', The Sydney Morning Herald 17 December, viewed 16 May 2014

- Vallero DA & Letcher TM 2013, Unravelling environmental disasters, Elsevier, Waltham, MA, ISBN 9780123970268

- Volesky B 1990, 'Removal and Recovery of Heavy Metals by Biosorption', in B Voleseky (ed.), Biosorption of Heavy Metals, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 7–44, ISBN 0849349176

- Waldron HA 1983, 'Did the Mad Hatter have Mercury Poisoning?', British Medical Journal, vol. 287, p. 1961, DOI:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1961

- Wanklyn JA & Chapman ET 1868, Water Analysis: A Practical Treatise on the Examination of Potable Water, Trübner & Co., London

- Whorton JG 2011, The Arsenic Century, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 9780199605996

- World Health Organization 2013, 'Stop lead poisoning in children', viewed 17 May 2014

- Worsztynowicz A & Mill W 1995, 'Potential Ecological Risk due to Acidification of Heavy Industrialized Areas - The Upper Silesia Case,' in JW Erisman & GJ Hey (eds), Acid Rain Research: Do We Have Enough Answers?, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 353–66, ISBN 0444820388

- Wright DA & Welbourn P 2002, Environmental Toxicology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0521581516

- Zhao HL, Zhu X & Sui Y 2006, 'The short-lived Chinese emperors', Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 54, no. 8, pp. 1295–6, DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00821.x