المسيحية في القرن 13

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) imperial church headed by Constantinople continued to assert its universal authority. By the 13th century this assertion was becoming increasingly irrelevant as the Eastern Roman Empire shrank and the Ottoman Turks took over most of what was left of the Byzantine Empire (indirectly aided by invasions from the West). The other Eastern European churches in communion with Constantinople were not part of its empire and were increasingly acting independently, achieving autocephalous status and only nominally acknowledging Constantinople's standing in the Church hierarchy. In Western Europe the Holy Roman Empire fragmented making it less of an empire as well.

High scholasticism and its contemporaries

Scholasticism originally began to reconcile the philosophy of the ancient classical philosophers with medieval Christian theology. It is not a philosophy or theology in itself, but a tool and method for learning which puts emphasis on dialectical reasoning. The primary purpose of scholasticism was to find the answer to a question or resolve a contradiction. It is most well known in its application in medieval theology, but was eventually applied to classical philosophy and many other fields of study.

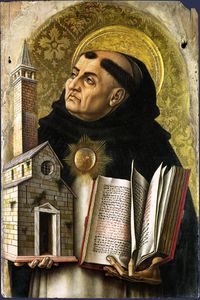

In the 13th century there was an attempted suppression of various groups perceived as heterodox, such as the Cathars and Waldensians and the associated rise of the mendicant orders (notably the Franciscans and Dominicans), in part intended as a form of orthodox alternative to the heretical groups. Those two orders quickly became contexts for some of the most intense scholastic theologizing, producing such 'high scholastic' theologians as Alexander of Hales (Franciscan) and Thomas Aquinas (Dominican), or the rather less obviously scholastic Bonaventure (Franciscan). There was also a flourishing of mystical theology, with women such as Mechthild of Magdeburg playing a prominent role. In addition, the century can be seen as period in which the study of Natural Philosophy that could anachronistically be called 'science' began once again to flourish in the hands of such men as Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon.

Notable authors include:

- Saint Dominic

- Albertus Magnus

- Robert Grosseteste

- Francis of Assisi

- Alexander of Hales

- Mechthild of Magdeburg

- Roger Bacon

- Bonaventure

- Thomas Aquinas

- Angela of Foligno

Western religious orders

The monastic orders, especially the Benedictines, Cistercians, and Premonstratensians, continued to have an important role in the Catholic Church throughout the 13th century. The Mendicant Orders, which focused on poverty, preaching and other forms of pastoral ministry, were founded at this time. The four Mendicant Orders recognized by the Second Council of Lyon are:

- The Order of Preachers (Dominicans), founded in 1215 by St. Dominic de Guzman.

- The Friars Minor (Franciscans), founded in 1209 by St. Francis of Assisi

- The Hermits of St. Augustine (Augustinians), founded in 1256 when different communities that followed the Rule of St. Augustine were united.

- The Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Carmelites), which were founded in the Holy Land in the 12th century but came to Europe in the 13th century.

Crusades

The Fourth Crusade, authorized by Innocent III in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Land but was soon subverted by Venetians who used the forces to sack the Christian city of Zara. Eventually the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, but rather than proceed to the Holy Land the crusaders instead sacked Constantinople and other parts of Asia Minor effectively establishing the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Minor. This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy; later crusades were sponsored by individuals. Thus, though Jerusalem was held for nearly a century and other strongholds in the Near East remained in Christian possession much longer, the crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms.

Crusades against Christians in the East by Roman Catholic crusaders was not exclusive to the Mediterranean though (see also the Northern Crusades and the Battle of the Ice). The sacking of Constantinople and the Church of Holy Wisdom and establishment of the Latin Empire as a seeming attempt to supplant the Orthodox Byzantine Empire in 1204 is viewed with some rancour to the present day. Many in the East saw the actions of the West as a prime determining factor in the weakening of Byzantium. This led to the empire's eventual conquest and fall to Islam. In 2004, Pope John Paul II extended a formal apology for the sacking of Constantinople in 1204; the apology was formally accepted by Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople. Many things that were stolen during this time: holy relics, riches, and many other items, are still held in various Western European cities, particularly Venice.

The crusades in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily eventually led to the demise of Islamic power in the regions; the Teutonic Knights expanded Christian domains in Eastern Europe; and the much less frequent crusades within Christendom, such as the Albigensian Crusade, achieved their goal of maintaining doctrinal unity.[1]

Fourth Crusade, 1202–1204

The Fourth Crusade was initiated in 1202 by Pope Innocent III, with the intention of invading the Holy Land through Egypt. Because the Crusaders lacked the funds to pay for the fleet and provisions that they had contracted from the Venetians, Doge Enrico Dandolo enlisted the crusaders to restore the Christian city of Zara (Zadar) to obedience. Because they subsequently lacked provisions and time on their vessel lease, the leaders decided to go to Constantinople, where they attempted to place a Byzantine exile on the throne. After a series of misunderstandings and outbreaks of violence, the Crusaders sacked the city in 1204 and established the so-called Latin Empire and a series of other Crusader states throughout the territories of the Greek Byzantine Empire. This is often seen as the final breaking point of the Great Schism between the Eastern Orthodox Church and (Western) Roman Catholic Church.

After the Sack of Constantinople, much of Asia Minor was brought under Roman Catholic rule, and the Latin Empire of the East was established. As the conquest by the European crusaders was not exclusive to the fourth crusade, many various kingdoms of European rule were established. After the fall of Constantinople to the Latin West the Empire of Nicaea was established, which was later to be the origin of the Greek monarchy that defeated the Latin forces of Europe and re-established Orthodox monarchy in Constantinople and Asia Minor.

Crusades against the Eastern Orthodox

Crusades against Christians in the East by Roman Catholic crusaders were not exclusive to the fourth crusade nor the Mediterranean. The sacking of Constantinople and the Church of Holy Wisdom, the destruction of the Monastery of Stoudios, Library of Constantinople and the establishment of the Latin Empire in Constantinople and also throughout West Asia Minor and Greece (see the Kingdom of Thessalonica, Kingdom of Cyprus) are considered definitive though. This is in light of perceived Roman Catholic atrocities not exclusive to the capital city of Constantinople in 1204 starting the period in the East referred to as Frangokratia. The establishment of the Latin Empire in 1204 was intended to supplant the Orthodox Byzantine Empire. This is symbolized by many Orthodox churches like Hagia Sophia and Church of the Pantokrator being converted into Roman Catholic properties and it is viewed with some rancour to the present day. Some of the European Christian community actively endorsed the attacking of Eastern Christians.[2]

This was preceded by a European backed attempted conquest of Byzantium, Greece, and Bulgaria and other Eastern Christian countries which led to the establishment of the Latin Empire of the East and the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople (with various other Crusader states).

The Teutonic Order's attempts to conquer Orthodox Russia (particularly the Republics of Pskov and Novgorod), an enterprise endorsed by Pope Gregory IX,[3] can also be considered as a part of the Northern Crusades. One of the major blows for the idea of the conquest of Russia was the Battle of the Ice in 1242. With or without the Pope's blessing, Sweden also undertook several crusades against Orthodox Novgorod. Many in the East saw the actions of the West in the Mediterranean as a prime determining factor in the weakening of Byzantium which led to the empire's eventual conquest and fall to Islam.[4]

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade was launched in 1209 to eliminate the heretical Cathars of Occitania (the south of modern-day France). It was a decade-long struggle that had as much to do with the concerns of northern France to extend its control southwards as it did with heresy. In the end, both the Cathars and the independence of southern France were exterminated.

After a papal legate was murdered by the Cathars in 1208, Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade.[5] Abuses committed during the crusade caused Innocent III to informally institute the first papal inquisition to prevent future aberrational practices and to root out the remaining Cathars.[6][7] Formalized under Pope Gregory IX, this Medieval inquisition executed an average of three people per year for heresy at its height.[7][8] Over time, other inquisitions were launched by the Church or secular rulers to prosecute heretics, to respond to the threat of Moorish invasion or for political purposes.[9] The accused were encouraged to recant their heresy and those who did not could be punished by penance, fines, imprisonment, torture or execution by burning.[9][10]

Children's Crusade

The Children's Crusade is a series of possibly fictitious or misinterpreted events of 1212. The story is that an outburst of the old popular enthusiasm led a gathering of children in France and Germany, which Pope Innocent III interpreted as a reproof from heaven to their unworthy elders. The leader of the French army, Stephen, led 30,000 children. The leader of the German army, Nicholas, led 7,000 children. None of the children actually reached the Holy Land; those who did not return home or settle along the route to Jerusalem either died from shipwreck or hunger, or were sold into slavery in Egypt or North Africa.

Fifth Crusade, 1217–1221

By processions, prayers, and preaching, the Church attempted to set another crusade afoot, and the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) formulated a plan for the recovery of the Holy Land. In the first phase, a crusading force from Austria and Hungary joined the forces of the king of Jerusalem and the prince of Antioch to take back Jerusalem. In the second phase, crusader forces achieved a remarkable feat in the capture of Damietta in Egypt in 1219, but under the urgent insistence of the papal legate, Pelagius, they launched a foolhardy attack on Cairo in July 1221. The crusaders were turned back after their dwindling supplies led to a forced retreat. A night-time attack by Sultan Al-Kamil resulted in a great number of crusader losses and eventually in the surrender of the army. Al-Kamil agreed to an eight-year peace agreement with Europe.

Sixth Crusade, 1228–1229

Emperor Frederick II had repeatedly vowed a crusade but failed to live up to his words, for which he was excommunicated by Pope Gregory IX in 1228. He nonetheless set sail from Brindisi, landed in Palestine, and through diplomacy he achieved unexpected success: Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem were delivered to the crusaders for a period of ten years.

In 1229 after failing to conquer Egypt, Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire made a peace treaty with Al-Kamil. This treaty allowed Christians to rule over most of Jerusalem, while the Muslims were given control of the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The peace brought about by this treaty lasted for about ten years.[11] Many of the Muslims though were not happy with Al-Kamil for giving up control of Jerusalem, and in 1244, following a siege, the Muslims regained control of the city.[12]

Seventh Crusade, 1248–1254

The papal interests represented by the Knights Templar brought on a conflict with Egypt in 1243, and in the following year a Khwarezmian force summoned by the Templars stormed Jerusalem. The crusaders were drawn into battle at La Forbie in Gaza. The crusader army and its Bedouin mercenaries were defeated by Baibars' force of Khwarezmian tribesmen. This battle is considered by many historians to have been the death knell to the Kingdom of Outremer.

Although this provoked no widespread outrage in Europe as the fall of Jerusalem in 1187 had done, Louis IX of France organized a crusade against Egypt from 1248 to 1254, leaving from the newly constructed port of Aigues-Mortes in southern France. It was a failure, and Louis spent much of the crusade living at the court of the crusader kingdom in Acre. In the midst of this crusade was the first Shepherds' Crusade in 1251.

Eighth Crusade, 1270

The Eighth Crusade was organized by Louis IX in 1270, again sailing from Aigues-Mortes, initially to come to the aid of the remnants of the crusader states in Syria. However, the crusade was diverted to Tunis, where Louis spent only two months before dying. For his efforts, Louis was later canonised.

Ninth Crusade, 1271–1272

The future Edward I of England undertook another expedition against Baibars in 1271, after having accompanied Louis on the Eighth Crusade. The Ninth Crusade was deemed a failure and ended the Crusades in the Middle East.[13]

In their later years, faced with the threat of the Egyptian Mamluks, the Crusaders' hopes rested with a Franco-Mongol alliance. Although the Mongols successfully attacked as far south as Damascus on these campaigns, the ability to effectively coordinate with Crusades from the west was repeatedly frustrated most notably at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260. The Mamluks eventually made good their pledge to cleanse the entire Middle East of the Franks. With the fall of Antioch (1268), Tripoli (1289), and Acre (1291), those Christians unable to leave the cities were massacred or enslaved, and the last traces of Christian rule in the Levant disappeared.[14][15]

Northern Crusades

[محل شك] The Teutonic Order's attempts to conquer Orthodox Russia (particularly the Republics of Pskov and Novgorod), an enterprise endorsed by Pope Gregory IX, can be considered as a part of the Northern Crusades. One of the major blows for the idea of the conquest of Russia was the Battle of the Ice in 1242. With or without the Pope's blessing, Sweden also undertook several crusades against Orthodox Novgorod.

Between 1232 and 1234, there was a crusade against the Stedingers. This crusade was special, because the Stedingers were not heathens or heretics, but fellow Roman Catholics. They were free Frisian farmers who resented attempts of the count of Oldenburg and the archbishop Bremen-Hamburg to make an end to their freedoms. The archbishop excommunicated them, and Pope Gregory IX declared a crusade in 1232. The Stedingers were defeated in 1234.

Aragonese Crusade

The Aragonese Crusade, or Crusade of Aragón, was declared by Pope Martin IV against the King of Aragón, Peter III the Great, in 1284 and 1285.

Crusade against the Tatars

In 1259 Mongols led by Burundai and Nogai Khan ravaged the principality of Halych-Volynia, Lithuania and Poland. After that Pope Alexander IV tried without success to create a crusade against the Blue Horde.

Second Council of Lyon

The Second Council of Lyon was convoked to act on a pledge by Byzantine emperor Michael VIII to reunite the Eastern church with the West.[16] Wishing to end the Great Schism that divided Rome and Constantinople, Gregory X had sent an embassy to Michael VIII Palaeologus, who had reconquered Constantinople, putting an end to the remnants of the Latin Empire in the East, and he asked Latin despots in the East to curb their ambitions. On June 29, 1274, Gregory X offered Mass in St John's Church, where both sides took part. The council declared that the Roman church possessed "the supreme and full primacy and authority over the universal Catholic Church."

The council was seemingly a success but did not provide a lasting solution to the schism; the emperor was anxious to heal the schism, but the Eastern clergy proved to be obstinate. However, Michael VII's son and successor Andronicus II repudiated the union.

Serbian Church

In 1217, Stefan Nemanjić was proclaimed King of Serbia, and various questions of the church reorganization were opened.[17] On 15 August 1219, during the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God, archimandrite Sava was consecrated by Patriarch Manuel I of Constantinople in Nicaea as the first Archbishop of the autocephalous (independent) Serbian Church. The patriarch of Constantinople and his Synod thus appointed Sava as the first archbishop of "Serbian and coastal lands."[18][19][20][21][22] In the same year, Archbishop Sava published Zakonopravilo (St. Sava's Nomocanon). Thus the Serbs acquired both forms of independence: political and religious.[23]

Archbishop Sava appointed several bishops, sending them around Serbia to organize their dioceses.[24] To maintain his standing as the religious and social leader, he continued to travel among the monasteries and lands to educate the people. In 1221 a synod was held in the Žiča monastery, condemning Bogomilism.[25]

Rus' Church

Mongol rule in Kievan Rus lasted from the 13th (Genghis Khan's army entered Kievan Rus in 1220s) through the 15th century, the Rus' church enjoyed a favored position, obtaining immunity from taxation in 1270. Through a series of wars with Muslim countries the church did indeed establish itself as the protector of Orthodoxy.

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- Christianization

- Timeline of Christianity#Middle Ages

- Timeline of Christian missions#Middle Ages

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#800–1453

- Chronological list of saints and blesseds in the 13th century

References

- ^ Brian Tierney and Sidney Painter, Western Europe in the Middle Ages 300–1475. 6th ed. (McGraw-Hill 1998)

- ^ ""The Sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders"". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books, 287. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- ^ "Fourth Crusade, 1202-1204" Even after Greek control of Byzantium was re-established, the empire never recovered the strength it had had even in 1200, and the sole effect of the fourth crusade was to weaken Europe's chief protection against the Turks.

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 112

- ^ Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages (2005), pp.144-147

- ^ أ ب Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church (2004), p. 132

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), p. 93

- ^ أ ب Black, Early Modern Italy (2001), pp.200-202

- ^ Casey, Early Modern Spain: A Social History (2002), pp.229-230

- ^ Lamb, Harold. The Crusades: The Flame of Islam, Doubleday (publisher) New York. 1931 pp.310-311.

- ^ "Crusades" In The Islamic World: past and Present, edited by John L. Esposito. Oxford Islamic Studies Online, http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article (accessed February 17, 2008).

- ^ Dore's Illustrations of the Crusades By Gustave Dore, Dore

- ^ Hetoum II (1289‑1297)

- ^ "Third Crusade: Siege of Acre". Archived from the original on 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ Wetterau, Bruce. World history. New York: Henry Holt and company. 1994.

- ^ Kalić 2017, p. 7-18.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, p. 383.

- ^ Blagojević 1993, p. 27-28.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 28, 42-43.

- ^ Ferjančić & Maksimović 2014, p. 37–54.

- ^ Marjanović 2018, p. 41–50.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 43, 68.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, pp. 222, 233.

Bibliography

- Blagojević, Miloš (1993). "On the National Identity of the Serbs in the Middle Ages". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 20–31. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ferjančić, Božidar; Maksimović, Ljubomir (2014). "Sava Nemanjić and Serbia between Epiros and Nicaea". Balcanica (45): 37–54. doi:10.2298/BALC1445037F. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_12894.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2017). "The First Coronation Churches of Medieval Serbia". Balcanica (48): 7–18. doi:10.2298/BALC1748007K.

- Marjanović, Dragoljub (2018). "Emergence of the Serbian Church in Relation to Byzantium and Rome" (PDF). Niš and Byzantium. 16: 41–50.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521074599.

Further reading

- Lawrence, C. H. Medieval Monasticism. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. ISBN 0-582-40427-4