الكاثوليكية في الصين

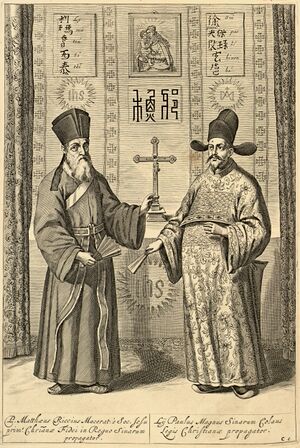

الكاثوليكية في الصين (تسمى تيانژو جيآو، 天主教، حرفياً، "ديانة سيد السماء"، انطلاقاً من المصطلح للرب المستخدم تقليدياً في اللغة الصينية من قِبل الكاثوليك) لها تاريخ طويل ومعقد. فقد تواجدت المسيحية في الصين في صيغ مختلفة منذ، على الأقل، أسرة تانگ في القرن الثامن. وإثر استيلاء الحزب الشيوعي الصيني على السلطة في 1949، تم طرد المبشرين الكاثوليك والپروتستانت من البلد، واُتـُهـِمت الديانة بأنها تجسيد للإمبريالية الغربية. وفي 1957، أسست الحكومة الصينية الجمعية الكاثوليكية الوطنية الصينية، التي رفضت سلطة الڤاتيكان وعينت أساقفتها بنفسها.

في 1 يوليو 2012، اعتقلت الصين الأسقف الكاثوليكي الذي عينه الڤاتيكان. وفي سابقة عالمية، تعين الصين الأسقف الكاثوليكي فيها. الڤاتيكان يعلن عدم اعترافه بمن اختارته الصين. [1]

المصطلحات الصينية للرب والمسيحية

المصطلحات المستخدمة للإشارة إلى الرب في اللغة الصينية تختلف حتى بين المسيحيين.

Arriving in China during the أسرة تانگ, the earliest Christian missionaries from the Church of the East referred to their religion as Jǐng جيآو (景教، حرفياً، "التعاليم اللامعة"). Originally, some Catholic missionaries and scholars advanced the use of Shàngdì (上帝, ، حرفياً "الامبراطور من أعلى")، as being more native to the Chinese language, but ultimately the Catholic hierarchy decided that the more Confucian term, تيانژو (天主, حرفياً، "سيد السماء")، was to be used, at least in official worship and texts. Within the Catholic Church, the term 'گونگ جيآو (公教، حرفياً "التعاليم الكونية") is not uncommon, this being also the original meaning of the word "catholic".

When Protestants finally arrived in China in the 19th c., they favored Shangdi over تيانژو. Many Protestants also use Yēhéhuá (耶和华, a transliteration of Jehovah)or Shēn (神), which generically means "god" or "spirit", although Catholic priests are called shénfù (神父, literally "spiritual father"). Meanwhile, the Mandarin Chinese transliteration of "Christ," used by all Christians, is Jīdū (基督).

جمهورية الصين الشعبية

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began targeting Christian missionaries and monasteries during the Chinese Civil War. Even as Protestants began fleeing the country, the Catholic Church ordered over 3,000 of its missionaries in China to remain even as the CCP won the war. After the proclamation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 by the CCP, the Catholic Church was initially allowed to operate independently but faced growing legal obstruction and scrutiny. All foreign missionaries were required to register with the government, and Chinese authorities interrogated Catholics and investigated hospitals and schools. It also forced many churches to close by issuing prohibitively high taxes. The Chinese government began mass arrests of foreign missionaries after intervening in the Korean War, but Catholics were ordered by the apostolic nuncio Antonio Riberi to remain and resist. Riberi and Bishop Tarcisio Martina were themselves arrested and expelled for false allegations that they were involved in a conspiracy to assassinate Mao Zedong. Mao also ordered the arrest and execution of all members of the Legion of Mary, which he believed was a paramilitary unit.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1950, the Holy See stated that participation in certain CCP-related organizations would result in excommunication from the Church.[1] In response, initiatives including Fr. Wang Liangzuo's "Guangyuan Declaration of Catholic Self-Reformation" gained support from Chinese Catholics.[1] In turn, apostolic nuncio Antonio Riberi circulated a letter denouncing such proposed reforms, and in March 1951 Fr. Li Weiguang and a group of 783 priests, nuns, and lay Catholics signed a declaration opposing what they viewed as Vatican interference and Western imperialism.[1]

China broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See in 1951, deporting Riberi to British Hong Kong.[1] The CCP framed these actions in terms of Chinese Catholics reclaiming their church in the context of broader opposition to Western imperialism.[1]

By the summer of 1953 the Catholic Church had been completely suppressed.[2]

Since then Catholicism, like all religions, was permitted to operate only under the supervision of the State Administration for Religious Affairs. All legal worship was to be conducted through state-approved churches belonging to the Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA), which did not accept the primacy of the Roman Pontiff. In addition to overseeing the practice of the Catholic faith, the CPA espoused politically oriented objectives as well. Liu Bainian, chairman of the CPA and the Bishops Conference of the Catholic Church in China (BCCCC), stated in a 2011 interview that the church needed individuals who "love the country and love religion: politically, they should respect the Constitution, respect the law, and fervently love the socialist motherland."[3]

Clergy who resisted this development were subject to oppression, including long imprisonments as in the case of Cardinal Kung, and torture and martyrdom as in the case of Fr. Beda Chang, S.J. Catholic clergy experienced increased supervision. Bishops and priests were forced to engage in degrading menial jobs to earn their living. Foreign missionaries were accused of being foreign agents, ready to turn the country over to imperialist forces.[4] The Holy See reacted with several encyclicals and apostolic letters, including Cupimus Imprimis, Ad Apostolorum principis, and Ad Sinarum gentem.

Some Catholics who recognized the authority of the Holy See chose to worship clandestinely due to the risk of harassment from authorities. Several underground Catholic bishops were reported as disappeared or imprisoned, and harassment of unregistered bishops and priests was common.[5] There were reports of Catholic bishops and priests being forced by authorities to attend the ordination ceremonies for bishops who had not gained Vatican approval.[3] Chinese authorities also had reportedly pressured Catholics to break communion with the Vatican by requiring them to renounce an essential belief in Catholicism, the primacy of the Roman Pontiff. In the past, however, authorities have permitted some Vatican-loyal churches to carry out operations.[5]

While Article 36 of China's Constitution provides for "freedom of religious belief" and non-discrimination on religious bases, it also states that "[n]o one shall use religion to engage in activities that disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the state's education system" and "[r]eligious groups and religious affairs shall not be subject to control by foreign forces."[6]

A major impediment to the re-establishment of relations between the Vatican and Beijing was the issue of who appoints the bishops. As a matter of maintaining autonomy and rejecting foreign intervention, the official church had no official contact with the Vatican and did not recognize its authority. In later years, however, the CPA allowed for unofficial Vatican approval of ordinations. Although the CPA continued to carry out some ordinations opposed by the Holy See, the majority of CPA bishops became recognized by both authorities.[7]

In a further sign of rapprochement between the Vatican and Beijing, Pope Benedict XVI invited four Chinese bishops, including two government recognized bishops, one underground bishop, and one underground bishop recently emerged into the registered church, to the October 2005 Synod on the Eucharist.[8]

On 27 May 2007, Pope Benedict XVI wrote a letter to Chinese Catholics "to offer some guidelines concerning the life of the Church and the task of evangelization in China".[9] In this letter (section 9), Pope Benedict acknowledges tensions:

As all of you know, one of the most delicate problems in relations between the Holy See and the authorities of your country is the question of episcopal appointments. On the one hand, it is understandable that governmental authorities are attentive to the choice of those who will carry out the important role of leading and shepherding the local Catholic communities, given the social implications that – in China as in the rest of the world – this function has in the civil sphere as well as the spiritual. On the other hand, the Holy See follows the appointment of Bishops with special care since this touches the very heart of the life of the Church, inasmuch as the appointment of Bishops by the Pope is the guarantee of the unity of the Church and of hierarchical communion.

Underground bishop Joseph Wei Jingyi of Qiqihar released a two-page pastoral letter in July 2007, asking his congregation to study and act on the letter of Pope Benedict XVI and naming the letter a "new milestone in the development of the Chinese Church."[10] In September 2007, a coadjutor bishop for the Guiyang Diocese was jointly appointed by the Vatican and the Chinese official Catholic church.[11]

Demographics

The number of Catholics is hard to estimate because of the large number of Christians who do not affiliate with either of the two state-approved denominations.[12][5]

Estimates in 2020 suggested that Catholics make up 0.69% of the population.[13]

The 2010 Blue Book of Religions, produced by the Institute of World Religions at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a research institution directly under the State Council, estimated Catholics in China to number about 5.7 million.[14] This Chinese government estimate only included members of the Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA). It did not include un-baptized persons attending Christian groups, non-adult children of Christian believers or other persons under age 18, and unregistered Christian groups.[12]

The Holy Spirit Study Centre in Hong Kong, which monitors the number of Chinese Catholic members, estimated in 2012 that there were 12 million Catholics in both branches of the Catholic Church.[15]

In 2017 Hebei Province had the largest Catholic Christian population in China, with 1 million Church members according to the local government.[16] Generally, Catholic institutions were dominant in North and Central regions of China.[12]

الاتفاقية المؤقتة بين الفاتيكان وجمهورية الصين الشعبية

On 22 September 2018, the Holy See and the People's Republic of China signed a two-year "Provisional Agreement between the Holy See and the People's Republic of China on the appointment of Bishops", set to expire on 22 October 2020. According to the communiqué released by the Holy See Press Office, the Provisional Agreement aimed to create "conditions for great collaboration at the bilateral level."[17] This was the first time that an agreement of cooperation has been jointly signed by the Holy See and China. The exact terms of the Provisional Agreement have not been publicly released but people who are familiar with the agreement stated that it allowed for the Holy See to review bishop candidates recommended by the government-sanctioned Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA) prior to appointment and consecration.[18] The Provisional Agreement granted veto power to the Holy See when reviewing the bishop nominees that the CPA has put forward. Anthony Yao Shun, bishop of Jining, was the first bishop appointed under the framework of the Provisional Agreement.[19] Pope Francis readmitted seven bishops appointed by the government without Pontifical mandate to full ecclesial communion in addition to the new appointments.[20] In a communiqué released by the Holy See on 22 October 2020,[21] the Holy See and China entered into a note verbale agreement to extend the Provisional Agreement for an additional two years, remaining in effect until 22 October 2022.[22]

While the agreement is viewed by the Holy See as an opportunity to increase their presence in China, many thought that it diminished the Holy See's authority over the local church because it shared decision making powers with an authoritarian government. Cardinal Joseph Zen, former archbishop of Hong Kong, strongly opposed the deal, stating that the agreement is an incredible betrayal of the Catholics in China.[23] As a response to the criticism, Pope Francis wrote a message to the Catholics of China and to the Universal Church on 26 September 2018 to provide context on how to view the Provisional Agreement.[24] Pope Francis recognized that the Provisional Agreement is experimental in nature and will not resolve other conflicts between the Holy See and China, but it will allow for both parties to "act more positively for the orderly and harmonious growth of the Catholic community in China."[25] China, on its part, also positively views the agreement, stating that it is willing to "further enhance understanding with the Vatican side and accumulate mutual trust, so that the momentum of active interaction between the two sides will continue to move forward."[26] Despite strong opposition from the White House and conservative Catholics, the Holy See and China extended the Provisional Agreement.[27]

In November 2020, a month after the Provisional Agreement was extended, China released the revised "Administrative Measures for Religious Clergy." The enforcement of the new rules took effect on 1 May 2021. The Administrative Measures prioritize the Sinicization of all religion. Religious professionals are obligated to carry out their duties within the scope provided by the laws, regulations and rules of the government.[28] The new rules do not consider the collaborative process set in place by the Provisional Agreement between the Holy See and China when appointing bishops. In Article XVI of the Administrative Measures, Catholic bishops are to be approved and consecrated by the government-sanctioned Chinese Catholic Bishops Conference. The document does not state that collaboration and approval from the Holy See to appoint bishops is required, going against the terms of the Provisional Agreement. Just a month before the release of the new rules, Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian had stated that China is willing to work together with the Vatican "to maintain close communication and consultation and advance the improvement of bilateral ties"[29] through the Provisional Agreement. Appointment of bishops without the consent of the Holy See violates the Catholic Church Canon Law 377.5, which states that "no rights and privileges of election, nomination, presentation, or designation of bishops are granted to civil authorities."[30]

In July 2022, Pope Francis stated that he hoped the Provisional Agreement would be renewed, describing the agreement as "moving well."[31] As of July 2022, six new bishops had been appointed under the agreement.[32]

According to Catholic charity Aid to the Church in Need, at least 20 priests were under arrest at some point in 2023, some of whom had been missing for several years.[33]

طالع أيضاً

- List of Roman Catholic missionaries in China

- الأعمدة الثلاث للكاثوليكية الصينية

- Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Hong Kong

- Chinese house church

- الكاردينال كونگ

- Maryknoll

- Chinese Catholic Bishops Conference

- Missions étrangères de Paris

- List of Catholic cathedrals in China

- List of Roman Catholic Dioceses in China

- الديانة في الصين

- المسيحية في الصين

- الكنيسة الأرثوذكسية الصينية

- الپروتستانتية في الصين

وصلات خارجية

- The Catholic Church in China by Giga-Catholic Information

- Beijing Northern Church – a Full Introduction to the Home of Beijing Diocese by ChinaReport.com

- Roman Catholic Church in China in Catholic Hierarchy

- Bible in Chinese, by Catholic Missionaries in Asia

- Father Vincent Lebbe

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/The Church in China "|The Church in China]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/The Church in China "|The Church in China]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Check|url=value (help)

المراجع

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من The Chinese repository, Volume 13، وهي مطبوعة من سنة 1844 وهي الآن مشاع عام في الولايات المتحدة.

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من The Chinese repository, Volume 13، وهي مطبوعة من سنة 1844 وهي الآن مشاع عام في الولايات المتحدة. هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China، بقلم Robert Samuel Maclay، وهي مطبوعة من سنة 1861 وهي الآن مشاع عام في الولايات المتحدة.

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China، بقلم Robert Samuel Maclay، وهي مطبوعة من سنة 1861 وهي الآن مشاع عام في الولايات المتحدة. هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4، بقلم Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General، وهي مطبوعة من سنة 1904 وهي الآن مشاع عام في الولايات المتحدة.

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4، بقلم Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General، وهي مطبوعة من سنة 1904 وهي الآن مشاع عام في الولايات المتحدة.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Yeh, Alice (2023-06-01). "Social Mobility, Migratory Vocations, and the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association". China Perspectives (133): 31–41. doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.15216. ISSN 2070-3449. S2CID 259562815.

- ^ Dikötter, Frank (2013). The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957 (1 ed.). London: Bloomsbury Press. pp. 115–120. ISBN 978-1-62040-347-1.

- ^ أ ب Congressional-Executive Commission on China, Annual Report 2011 Archived 13 فبراير 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 10 October 2011.

- ^ Giovannetti, 232

- ^ أ ب ت US State Dept 2022 report

- ^ "Constitution of the People's Republic of China". 2022-07-09. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

- ^ Tim Gardam, Christians in China: Is the country in spiritual crisis? BBC, 11 September 2011.

- ^ "Missing Page Redirect". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Letter to the Bishops, Priests, Consecrated Persons and Lay Faithful of the Catholic Church in the People's Republic of China (May 27, 2007) - BENEDICT XVI". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Underground" bishop urges faithful to implement Pope's letter, Catholic News Agency, July 2007

- ^ "Vatican approval for Guiyang Episcopal ordination made public". Asia News. 9 October 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life: "Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population - Appendix C: Methodology for China" Archived 17 يوليو 2013 at the Wayback Machine 19 December 2011

- ^ The ARDA website, retrieved 2023-08-28

- ^ U.S Department of State, International Religious Freedom Report 2013: China

- ^ Estimated Statistics for Chinese Catholic 2012, Holy Spirit Study Centre

- ^ 天主教 Archived 22 سبتمبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine 河北省民族宗教事务厅

- ^ "Communiqué concerning the signing of a Provisional Agreement between the Holy See and the People's Republic of China on the appointment of Bishops". press.vatican.va. Holy See Press Office. 22 September 2018. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018.

- ^ Rocca, Francis X.; Dou, Eva (2018-09-22). "Vatican and China Sign Deal Over Bishops, Allowing Pope a Veto". Wall Street Journal (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0099-9660.

- ^ Donnini, Debora (2019-08-28). "China, consecration of first bishop following Provisional Agreement - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Briefing Note about the Catholic Church in China". press.vatican.va. Holy See Press Office. 2018-09-22. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Communiqué on the extension of the Provisional Agreement between the Holy See and the People's Republic of China regarding the appointment of Bishops, 22 October 2020". press.vatican.va. Holy See Press Office. 2020-10-22. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Holy See and China renew Provisional Agreement for 2 years - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va (in الإنجليزية). 2020-10-22. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020.

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (2018-09-22). "Vatican signs historic deal with China – but critics denounce sellout". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 22 September 2018.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason; Johnson, Ian (2018-09-22). "China and Vatican Reach Deal on Appointment of Bishops". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ "Message of the Holy Father to the Catholics of China and to the Universal Church". www.vatican.va. The Vatican. 2018-09-26. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Wang Yi Meets with Foreign Minister Paul Gallagher of the Vatican at Request". www.fmprc.gov.cn. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 2020-02-15. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020.

- ^ Winfield, Nicole (2020-10-22). "Vatican, China extend bishop agreement over US opposition". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Measures on the Management of Religious Professionals (Draft for Solicitation of Comments)". China Law Translate (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-11-18. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian's Regular Press Conference on October 22, 2020". www.fmprc.gov.cn. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 2020-10-22. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - Book II - The People of God - Part II. (Cann. 368-430)". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019.

- ^ "Pope hopes deal with China on bishop appointments will be renewed soon | South China Morning Post". 2022-07-09. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Pope hopes deal with China on bishop appointments will be renewed soon | South China Morning Post". 2022-07-09. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ ACN (2024-01-09). "Dozens of priests arrested in 2023 as authoritarian regimes crack down on Church". ACN International (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2024-04-26.

- Wise Man from the West, Vincent Cronin, Fortuna Books, لندن, 1955 (on Matteo Ricci)

- Jesuits at the Court of Peking, C. W. Allen, Kelly & Walsh, Shanghai, c.1933

- John of Montecorvino

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2023

- CS1 errors: URL

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- الكنيسة الكاثوليكية الرومانية في الصين

- الديانة في جمهورية الصين الشعبية