ناناك

گورو ناناك | |

|---|---|

لوحة جدارية من القرن 19 من گوروداوا بابا أتال تصور ناناك. | |

| شخصية | |

| ولد | ناناك 15 أبريل 1469 (كاتاك پورانماشي، بحسب التقاليد السيخية)[1] |

| توفي | 15 أبريل 1469 (70 عاماً) |

| المثوى | گوراداوا داربار صاحب كرتارپور، كارتارپور، الپنجاب، پاكستان |

| الديانة | السيخية |

| الأطفال | سري تشاند لاكمي داس |

| الوالدان | الأب: مهتا كالو الأم: ماتا تريپتا |

| معروف بـ |

|

| أسماء أخرى | السيد الأول Peer Balagdaan (أفغانستان)[2] Nanakachryaya (in Sri Lanka)[3] ناناك لاما (في التبت)[4] Guru Rinpoche (في السيخية وبوتان)[5] Nanak Rishi (في نيپل)[6] ناناك پير (في العراق)[7] ڤالي هندو (في السعودية)[8] ناناك ڤالي (في مصر)[9] ناناك كادامدار (في روسيا)[10] بابا فوسا (الصين)[11] |

| التوقيع |  |

| مناصب رفيعة | |

| مقره في | كارترپور |

| تابعه | گورو أنگاد |

| هذا المقال جزء من سلسلة عن |

| السيخية |

|---|

|

|

|

گورو ناناك [12] (بالپنجابي: ਗੁਰੂ ਨਾਨਕ, هندي: गुरु नानक، أردو: گرونانک، ويُعرف أيضاً بلقب "بابا نانك") (عاش 15 أبريل 1469-22 سبتمبر 1539) هو الگورو الأول ومؤسس الديانة السيخية.

يقال أن ناناك سافر في جميع أنحاء آسيا لتعليم الناس رسالة إيك أونكار (بالپنجابي: ੴ)، الذي يسكن في كل من مخلوقاته ويشكل الحقيقة الأبدية.[13] ومن خلال هذا المفهوم، سيؤسس منصة روحية واجتماعية وسياسية فريدة من نوعها، قائمة على المساواة والحب الأخوي والخير والفضيلة.[14][15][16]

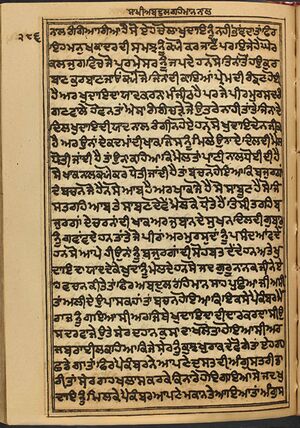

تم تسجيل كلمات ناناك على شكل 974 ترنيمة شعرية، أو شابدا، في الكتاب السيخي المقدس، گورو گرانث صاحب، حيث تعتبر بعض الصلوات الرئيسية جاپجي صاحب (بالپنجابي: jap؛ جي وصاحب هي لاحقات تدل على الاحترام)؛ آسا دي ڤار ('قصيدة الأمل')؛ and the سيد گوست ('المناقشة مع سيداس'). كجزء من المعتقد الديني السيخي فإن كل الگوروات اللاحقين قد ورثوا قداسته وسلطته الدينية وحملوا اسم "ناناك" في نسبهم. يُحتفى بعيد ميلاده سنوياً في گورو ناناك گورپوراب في جميع أنحاء الهند.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

سيرته

مولده

وُلد ناناك (1469)، في الپنجاب بالقرب من لاهور في باكستان، في بلدة تسمى الآن "ناناك صاحب". وكان قد نشأ نشأة هندوسية وعمل لدى المسلمين وكان محباً للإسلام من جهة ومشدود لتربيته الهندوسية مما دفعه للتقريب بين الديانتين. ولد ناناك في أسرة وضيعة المكانة في طبقة تدعى طبقة الويشي وهي طبقة بين طبقة الكشاتريا والشودري (المنبوذين).

عمل ناناك في شبابه عند حاكم سلطانپور، في المحاسبة مما أكسبه خبرة في الحياة التجارية، واغتنى في وجوده في سلطانبور وعرف المزيد عن الإسلام تعرف على عازف ربابة اسمه ماردانا وهو مسلم الديانة، وشكلا معاً فريقاً غنائياً، كان ناناك يؤلف الأناشيد ويلحنها ماردانا على الربابة لفرقة للإنشاد الديني التي كان يلحنها على ربابة ماردانا. وأقاما معاً مطعم صغير لكل الفئات من المسلمين والهندوس، مما أعطى أتصالاً واسعاً بين گورو ناناك والمترددين على المطعم.

وعندما بلغ الگورو ناناك الثلاثين من عمره، اختفى عن الأنظار لمدة ثلاثة أيام، ثم ظهر مدعياً أنه رسول من عند الله وهو مقتنع بذلك، لكل المسلمين والهندوس ولكل الفئات وللصالحين والملتزمين والصالحين أيضاً للأديان الأخرى.

ثم خرج لرحلة تبشير لكل المدن والحواضر المهمة في التبت ومكة المكرمة والمدينة المنورة وبغداد والهند كلها وكل شرق أسيا ولكن الغزو المغولي للهند اضطره أن يوقف رحلاته وقضى بقية حياته في قرية كارترپور التي أنشاء فيها أول معبد للسيخ إلى أن مات هناك في عام (1539).

وبالرغم من أن مسار وأحداث رحلته غير مؤكدين، فهناك شبه اتفاق على أنه قام بأربع رحلات كبرى، قطعت آلاف الكيلومترات؛ الجولة الأولى كانت شرقية إلى البنغال وأسام، والجولة الثانية كانت جنوبية إلى تاميل نادو، والجولة الثالثة شمالية إلى كشمير ولداخ والتبت، والجولة النهائية كانت غربية إلى بغداد ومكة والمدينة في الجزيرة العربية.[17] وفي مكة، وجد بعضهم گورو ناناك نائماً وقدماه في اتجاه الكعبة[18] فعنـَّفه القاضي ركن الدين. فرد عليه الگورو ناناك طالباً منه أن يدله على اتجاه لا يوجد فيه الله أو بيت من بيوت الله. ففهم القاضي المعنى الذي أراده ناناك إيصاله وهو "حيثما تولوا فثم وجه الله".[18] فبـُهت القاضي بتعجب.

وذكر أن كل أتباعه كان اسمهم في بادئ الأمر بنتيز ناناك أي المتحدين مع ناناك ولكن بعد ذلك أصبح اسمهم "گورو" أي المعلمين.

أسفار (Udasis)

During first quarter of the 16th century, Nanak went on long udasiya ('journeys') for spiritual pursuits. A verse authored by him states that he visited several places in "nau-khand" ('the nine regions of the earth'), presumably the major Hindu and Muslim pilgrimage centres.[19]

Some modern accounts state that he visited Tibet, most of South Asia, and Arabia, starting in 1496 at age 27, when he left his family for a thirty-year period.[20][21][22] These claims include Nanak's visit to Mount Sumeru of Indian mythology, as well as Mecca, Baghdad, Achal Batala, and Multan, where he would debate religious ideas with opposing groups.[23] These stories became widely popular in the 19th and 20th century, and exist in many versions.[24][23]

In 1508, Nanak visited the Sylhet region in Bengal.[بحاجة لمصدر] The janamsakhis suggest that Nanak visited the Ram Janmabhoomi temple in Ayodhya in 1510–11 CE.[25]

The Baghdad inscription remains the basis of writing by Indian scholars that Guru Nanak journeyed in the Middle East, with some claiming he visited Jerusalem, Mecca, Vatican, Azerbaijan and Sudan.[26]

خلافات

The hagiographic details are a subject of dispute, with modern scholarship questioning the details and authenticity of many claims. For example, Callewaert and Snell (1994) state that early Sikh texts do not contain such stories.[23] From when the travel stories first appear in hagiographic accounts of Guru Nanak, centuries after his death, they continue to become more sophisticated as time goes on, with the late phase Puratan version describing four missionary journeys, which differ from the Miharban version.[23][27]

Some of the stories about Guru Nanak's extensive travels first appear in the 19th-century Puratan janamsakhi, though even this version does not mention Nanak's travel to Baghdad.[23] Such embellishments and insertion of new stories, according to Callewaert and Snell (1993), closely parallel claims of miracles by Islamic pirs found in Sufi tadhkirahs of the same era, giving reason to believe that these legends may have been written in a competition.[28][23]

Another source of dispute has been the Baghdad stone, bearing an inscription[مطلوب توضيح] in a Turkish script. Some interpret the inscription as saying Baba Nanak Fakir was there in 1511–1512; others read it as saying 1521–1522 (and that he lived in the Middle East for 11 years away from his family). Others, particularly Western scholars, argue that the stone inscription is from the 19th century and the stone is not a reliable evidence that Nanak visited Baghdad in early 16th century.[29] Moreover, beyond the stone, no evidence or mention of his journey in the Middle East has been found in any other Middle Eastern textual or epigraphical records. Claims have been asserted of additional inscriptions, but no one has been able to locate and verify them.[30]

Novel claims about his travels, as well as claims such as his body vanishing after his death, are also found in later versions and these are similar to the miracle stories in Sufi literature about their pirs. Other direct and indirect borrowings in the Sikh janamsakhis relating to legends around his journeys are from Hindu epics and puranas, and Buddhist Jataka stories.[24][31][32]

سيَر مكتوبة بعد وفاته

The earliest biographical sources on Nanak's life recognised today are the janamsakhis ('birth stories'), which recount the circumstances of his birth in extended detail.

Gyan-ratanavali is the janamsakhi attributed to Bhai Mani Singh, a disciple of Guru Gobind Singh[مطلوب توضيح] who was approached by some Sikhs with a request that he should prepare an authentic account of Nanak's life. As such, it is said that Bhai Mani Singh wrote his story with the express intention of correcting heretical accounts of Nanak.

One popular janamsakhi was allegedly written by Bhai Bala, a close companion of Nanak. However, the writing style and language employed have left scholars, such as Max Arthur Macauliffe, certain that they were composed after his death.[33] According to such scholars, there are good reasons to doubt the claim that the author was a close companion of Guru Nanak and accompanied him on many of his travels.

Bhai Gurdas, a scribe of the Guru Granth Sahib, also wrote about Nanak's life in his vars ('odes'), which were compiled some time after Nanak's life, though are less detailed than the janamsakhis.

التعاليم والذكرى

Nanak's teachings can be found in the Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib, as a collection of verses recorded in Gurmukhi.[بحاجة لمصدر]

There are three competing theories on Nanak's teachings.[34] The first, according to Cole and Sambhi (1995, 1997), based on the hagiographical Janamsakhis,[35] states that Nanak's teachings and Sikhism were revelations from God, and not a social protest movement, nor an attempt to reconcile Hinduism and Islam in the 15th century.[36]

The second theory states that Nanak was a Guru, not a prophet. According to Singha (2009):[37]

Sikhism does not subscribe to the theory of incarnation or the concept of prophet hood. But it has a pivotal concept of Guru. He is not an incarnation of God, not even a prophet. He is an illumined soul.

The third theory is that Guru Nanak is the incarnation of God. This has been supported by many Sikhs including Bhai Gurdas, Bhai Vir Singh, Santhok Singh and is supported by the Guru Granth Sahib.[بحاجة لمصدر] Bhai Gurdas says:[38]

ਗੁਰ ਪਰਮੇਸਰੁ ਇਕੁ ਹੈ ਸਚਾ ਸਾਹੁ ਜਗਤੁ ਵਣਜਾਰਾ।

The Guru and God are one; He is the true master and the whole world craves for Him.

Additionally, in the Guru Granth Sahib, it is stated:[39]

ਨਾਨਕ ਸੇਵਾ ਕਰਹੁ ਹਰਿ ਗੁਰ ਸਫਲ ਦਰਸਨ ਕੀ ਫਿਰਿ ਲੇਖਾ ਮੰਗੈ ਨ ਕੋਈ ॥੨॥

O Nanak, serve the Guru, the Lord Incarnate; the Blessed Vision of His Darshan is profitable, and in the end, you shall not be called to account. ||2||

Guru Ram Das says:[40]

ਗੁਰ ਗੋਵਿੰਦੁ ਗੋੁਵਿੰਦੁ ਗੁਰੂ ਹੈ ਨਾਨਕ ਭੇਦੁ ਨ ਭਾਈ ॥੪॥੧॥੮॥

The Guru is God, and God is the Guru, O Nanak; there is no difference between the two, O Siblings of Destiny. ||4||1||8||

The hagiographical Janamsakhis were not written by Nanak, but by later followers without regard for historical accuracy, containing numerous legends and myths created to show respect for Nanak.[41] In Sikhism, the term revelation, as Cole and Sambhi clarify, is not limited to the teachings of Nanak. Rather, they include all Sikh Gurus, as well as the words of men and women from Nanak's past, present, and future, who possess divine knowledge intuitively through meditation. The Sikh revelations include the words of non-Sikh bhagats (Hindu & Muslim devotees), some who lived and died before the birth of Nanak, and whose teachings are part of the Sikh scriptures.[42]

The Adi Granth and successive Sikh Gurus repeatedly emphasised, suggests Mandair (2013), that Sikhism is "not about hearing voices from God, but it is about changing the nature of the human mind, and anyone can achieve direct experience and spiritual perfection at any time."[34] Nanak emphasised that all human beings can have direct access to God without rituals or priests.[20]

The concept of man as elaborated by Nanak, states Mandair (2009), refines and negates the "monotheistic concept of self/God," where "monotheism becomes almost redundant in the movement and crossings of love."[43] The goal of man, taught the Sikh Gurus, is to end all dualities of "self and other, I and not-I," attaining the "attendant balance of separation-fusion, self-other, action-inaction, attachment-detachment, in the course of daily life."[43]

Nanak, and other Sikh Gurus emphasised bhakti ('love', 'devotion', or 'worship'), and taught that the spiritual life and secular householder life are intertwined.[44] In the Sikh perspective, the everyday world is part of an infinite reality, where increased spiritual awareness leads to increased and vibrant participation in the everyday world.[45] Nanak described living an "active, creative, and practical life" of "truthfulness, fidelity, self-control and purity" as being higher than the metaphysical truth.[46]

Through popular tradition, Nanak's teaching is understood to be practised in three ways:[47]

- Vand Shhako (بالپنجابي: ਵੰਡ ਛਕੋ): Share with others, help those who are in need, so you may eat together;

- Kirat Karo ('work honestly'): Earn an honest living, without exploitation or fraud; and

- Naam Japo (بالپنجابي: ਨਾਮ ਜਪੋ): Meditate on God's name, so to feel His presence and control the five thieves of the human personality.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الذكرى

Nanak is the founder of Sikhism.[48][49] The fundamental beliefs of Sikhism, articulated in the sacred scripture Guru Granth Sahib, include faith and meditation on the name of the one creator; unity of all humankind; engaging in selfless service, striving for social justice for the benefit and prosperity of all; and honest conduct and livelihood while living a householder's life.[50][51][52]

The Guru Granth Sahib is worshipped as the supreme authority of Sikhism and is considered the final and perpetual guru of Sikhism. As the first guru of Sikhism, Nanak contributed a total of 974 hymns to the book.[53]

التأثير

Many Sikhs believe that Nanak's message was divinely revealed, as his own words in Guru Granth Sahib state that his teachings are as he has received them from the Creator Himself. The critical event of his life in Sultanpur, in which he returned after three days with enlightenment, also supports this belief.[54][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

Many modern historians give weight to his teachings' linkage with the pre-existing bhakti,[55] sant,[i] and wali of Hindu/Islamic tradition.[56] Scholars state that in its origins, Nanak and Sikhism were influenced by the nirguni ('formless God') tradition of the Bhakti movement in medieval India.[ii] However, some historians do not see evidence of Sikhism as simply an extension of the Bhakti movement.[57][58] Sikhism, for instance, disagreed with some views of Bhakti saints Kabir and Ravidas.[57][59]

The roots of the Sikh tradition are perhaps in the sant-tradition of India whose ideology grew to become the Bhakti tradition.[iii] Fenech (2014) suggests that:[56]

Indic mythology permeates the Sikh sacred canon, the Guru Granth Sahib and the secondary canon, the Dasam Granth and adds delicate nuance and substance to the sacred symbolic universe of the Sikhs of today and of their past ancestors.[iv]

في البهائية

In a letter, dated 27 October 1985, to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of India, the Universal House of Justice stated that Nanak was endowed with a "saintly character" and that he was:[61]

...inspired to reconcile the religions of Hinduism and Islám, the followers of which religions had been in violent conflict.... The Bahá'ís thus view Guru Nanak as a 'saint of the highest order'.

في الهندوسية

Nanak is highly influential amongst Punjabi Hindus and Sindhi Hindus, the majority of whom follow Nanakpanthi teachings. [62][63]

في البوذية التبتية وبون

Trilochan Singh claims that, for centuries, Tibetans have been making pilgrimages to the Golden Temple shrine in Amritsar to pay homage to Guru Nanak's memory.[64] However, Tibetans seem to have confused Nanak with the visit of Padmasambhava centuries earlier, and have superimposed details of Padmasambhava onto Nanak out of reverence (believing the essence of both figures is one and the same) or mistaken chronology.[note 1][65] According to Tibetan scholar Tarthang Tulku, many Tibetans believe Guru Nanak was an incarnation of Padmasambhava.[66] Both Buddhist and Bon Tibetans made pilgrimages to the Golden Temple in Amritsar, however they revered the site for different reasons.[67]

Between 1930 and 1935, the Tibetan spiritual leader, Khyungtrül Rinpoche (Khyung-sprul Rinpoche), travelled to India for a second time, visiting the Golden Temple in Amritsar during this visit.[68][67] Whilst visiting Amritsar in 1930 or 1931, Khyung-sprul and his Tibetan entourage walked around the Golden Temple while making offerings.[68] Khyung-sprul referred to the Golden Temple as "Guru Nanak's Palace" (Tibetan: Guru Na-nig-gi pho-brang).[68] Khyung-sprul returned to the Golden Temple in Amritsar for another time during his third and final visit to India in 1948.[68]

Several years later after the 1930–31 visit of Khyung-sprul, a Tibetan Bonpo monk by the name of Kyangtsün Sherab Namgyel (rKyang-btsun Shes-rab-rnam rgyal) visited the Golden Temple at Amritsar and offered the following description:[68]

"Their principal gshen is the Subduing gshen with the 'bird-horns'. His secret name is Guru Nanak. His teachings were the Bon of Relative and Absolute Truth. He holds in his hand the Sword of Wisdom . . . At this holy place the oceanic assembly of the tutelary gods and buddhas . . . gather like clouds"

— Kyangtsün Sherab Namgyel

في الإسلام

الأحمدية

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community consider Guru Nanak to have been a Muslim saint and that Sikhism derived from Sufism.[69] They believe Guru Nanak sought to educate Muslims about the "real teachings" of Islam.[69] Writing in 1895, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad defended Nanak from the accusations that had been made by the Arya Samajist Dayananda Saraswati, and asserted that Nanak was a Muslim.[69] According to Abdul Jaleel, Nanak being a Muslim is supported by a chola inscribed with Quranic verses that is attributed to having been belonging to him.[70]

في الثقافة الشعبية

- A Punjabi movie was released in 2015 named Nanak Shah Fakir, which is based on the life of Nanak, directed by Sartaj Singh Pannu[بحاجة لمصدر]

- Allegory: A Tapestry of Guru Nanak's Travels is a 2021–22 docuseries about Nanak's travels in nine different countries[بحاجة لمصدر]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أماكن زارها

أوتاراخند

أندرا پرادش

- Gurudwara Pehli Patshahi Guntur, Andhra Pradesh

بيهار

دلهي

- Gurdwara Nanak Piao, دلهي

- Gurudwara Majnu Ka Tila, Delhi[71][مطلوب مصدر أفضل]

گجرات

- Gurdwara Pehli Patshahi, Lakhpat, Gujarat

هاريانا

جمو وكشمير

پنجاب

- Gurudwara Shri Ber Sahib, Sultanpur Lodhi

- Gurudwara Shri Hatt Sahib, Sultanpur Lodhi

- Gurudwara Shri Kothri Sahib, Sultanpur Lodhi

- Gurudwara Shri Guru Ka Bagh, Sultanpur Lodhi

- Gurudwara Shri Sant Ghat, Sultanpur Lodhi

- Gurudwara Shri Antaryamta, Sultanpur Lodhi

- Dera Baba Nanak

- Gurudwara Manji Sahib, Kiratpur Sahib

- Achal Batala[72]

سيكيم

- Gurudwara Nanak Lama, Chungthang, Sikkim

- Gurudongmar Lake

أوديشا

- Gurdwara Guru Nanak Datan Sahib, Cuttack, Odisha

- Gurdwara Bauli Math Sahib, Puri, Odisha

پاكستان

- Nankana Sahib

- Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, Kartarpur

- Gurdwara Sacha Sauda, Farooqabad

- Sultanpur Lodhi

- Gurdwara Rori Sahib, Gujranwala

- Gurdwara Beri Sahib, Sialkot

- Gurdwara Panja Sahib, Hasan Abdal

- Gurudwara Chowa Sahib, Rohtas Fort

- Narowal

- Dudhu Chak

بنگلادش

أفغانستان

إيران

- Gurudwara Pehli Patshahi, Mashhad

العراق

سريلانكا

- Gurudwara Pehli Patshahi Batticaloa

- Koti, now known as Kotikawatta

الحجاز

أسس الرسالة في البداية

كانت أسس الرسالة في البداية شديدة البساطة ولم يكن هناك أي طقوس مثل (الصلاة والصوم والحج) في عهد ناناك ولم يترك ناناك وراءه كلمة واحدة مكتوبة ولم يكن للسيخ كتاب واحد فيه تعاليمهم حتى عهد الگورو الخامس أرجان التي ألف كتاب أدي گرانت.

أسس الرسالة

- الكد والعناء في العمل.

- عدم الإيمان بالوحي وفي اعتقاده أن الله ينير قلب من يريده أن يهدي خلقه.

- رفض تمثيل الإله في صور وتماثيل.

- الإيمان بأن الله واحد لا يتغير ولا يوصف ولا يُرى ولا يتجسد.

- كان يأمر بالتقشف لكته لم يامُر بالزهد.

- ممارسة الإحسان والبر.

- التامل الروحي لأن التأمل الروحي في رأيه ينير القلب ويجعل الإنسان يرى الله في خلقه.

- التأمل في عقيدته في المدائح التي توجد في الأناشيد التي يتلوها الإنسان.

أهم أعماله

- إنشاء عقيدته التي تدعي للأله الواحد والتقريب بين الهندوسية و الإسلام.

- نشر عقيدته في الحضر وترحاله للتبشير بعقيدته.

- بناء أول معبد للسيخ في كارتربور التي توفى فيها عام 1539.

المصادر

- ^ Gupta 1984, p. 49.

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "Booklet on Guru Nanak Dev's teachings released". Tribuneindia News Service (in الإنجليزية).

Rare is a saint who has travelled and preached as widely as Guru Nanak Dev. He was known as Nanakachraya in Sri Lanka, Nanak Lama in Tibet, Guru Rimpochea in Sikkim, Nanak Rishi in Nepal, Nanak Peer in Baghdad, Wali Hind in Mecca, Nanak Vali in Misar, Nanak Kadamdar in Russia, Baba Nanak in Iraq, Peer Balagdaan in Mazahar Sharif and Baba Foosa in China, said Dr S S Sibia, director of Sibia Medical Centre.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Baker, Janet (2 October 2019). "Guru Nanak: 550th birth anniversary of Sikhism's founder: Phoenix Art Museum, The Khanuja Family Sikh Art Gallery, 17 August 2019–29 March 2020". Sikh Formations. 15 (3–4): 499. doi:10.1080/17448727.2019.1685641. S2CID 210494526.

- ^ Guru Nanak may be referred to by many other names and titles such as Baba Nanak أو Nanak Shah.

- ^ Hayer 1988, p. 14.

- ^ Sidhu 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Khorana 1991, p. 214.

- ^ Prasoon 2007.

- ^ Dr Harjinder Singh Dilgeer (2008). Sikh Twareekh. Belgium & India: The Sikh University Press.

- ^ أ ب Guru Nanak: A Global Vision — Dr Inderpal Singh and Madan jit Kaur

- ^ Grewal 1998, p. 7.

- ^ أ ب BBC: Religions 2011.

- ^ Dilgeer 2008.

- ^ Johal 2011, pp. 125, note 1.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Callewaert & Snell 1994, pp. 26–7.

- ^ أ ب Lorenzen 1995.

- ^ Garg 2019.

- ^ Gulati 2008, pp. 316–319.

- ^ Lorenzen 1995, pp. 41–2.

- ^ McLeod 2007, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Ménage 1979, pp. 16–21.

- ^ McLeod 2004, pp. 127–31.

- ^ Oberoi 1994, p. 55.

- ^ Callewaert & Snell 1994, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Macauliffe 2004.

- ^ أ ب Mandair 2013, pp. 131–34.

- ^ Cole & Sambhi 1995, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Cole & Sambhi 1997, p. 71.

- ^ Singha 2009a, p. 104.

- ^ "Vaaran Bhai Gurdas:- Vaar1-Pauri17-ਜੁਗ ਗਰਦੀ-Anachy of the agesਵਾਰਾਂ ਭਾਈ ਗੁਰਦਾਸ; :-SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "Ang 306 of Guru Granth Sahib Ji - SikhiToTheMax". www.sikhitothemax.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji -: Ang : 442 -: ਸ਼੍ਰੀ ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ ਜੀ :- SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ Singh 2011, pp. 2–8.

- ^ Cole & Sambhi 1995, pp. 46, 52–3, 95–6, 159.

- ^ أ ب Mandair 2009, pp. 372–73.

- ^ Nayar & Sandhu 2007, p. 106.

- ^ Kaur 2004, p. 530.

- ^ Marwha 2006, p. 205.

- ^ McLeod 2009, pp. 139–40.

- ^ Cole & Sambhi 1978, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Moreno & Colino 2010, p. 207.

- ^ Kalsi 2007, pp. 41–50.

- ^ Cole & Sambhi 1995, p. 200.

- ^ Teece 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Shackle & Mandair 2013, pp. xviii–xix.

- ^ Singh 1982, pp. 12, 18.

- ^ Lorenzen 1995, pp. 1–2.

- ^ أ ب Fenech 2014.

- ^ أ ب Singha 2009b, p. 8.

- ^ Grewal 1998, pp. 28–.

- ^ Pruthi 2004, pp. 202–03.

- ^ Rinehart 2011

- ^ Sarwal 1996.

- ^ Kalhoro, Zulfiqar Ali (13 April 2018). "Nanakpanthi Saints of Sindh".

- ^ Singh, Inderjeet (1 October 2017). "Inderjeet Singh (2017). Sindhi Hindus & Nanakpanthis in Pakistan. Abstracts of Sikh Studies, Vol. XIX, No.4. p35-43". Abstracts of Sikh Studies – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Singh, Trilochan (1969). Guru Nanak: Founder of Sikhism: A Biography. Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee.

- ^ Gill, Savinder Kaur; Wangmo, Sonam (2019). Two Gurus One Message: The Buddha and Guru Nanak: Legacy of Liberation, Egalitarianism and Social Justice. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. pp. 302–304.

- ^ Chauhan, G. S.; Rajan, Meenakshi (January 2019). Shri Guru Nanak Dev: Life, Travels and Teachings (2nd ed.). All India Pingalwara Charitable Society Amritsar. pp. 176–178.

- ^ أ ب Lucia Galli, “Next stop, Nirvana. When Tibetan pilgrims turn into leisure seekers”, Mongolian and Siberian, Central Asian and Tibetan Studies [Online], 51 | 2020, posted online on December 9, 2020, accessed on May 21, 2024. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4697; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/emscat.4697

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج McKay, Alex (2013). Pilgrimage in Tibet. Routledge. ISBN 9781136807169.

- ^ أ ب ت Raza, Ansar. "Baba Guru Nanak – A Muslim Saint". Al Islam. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Jaleel, Abdul (March 1993). "Birth of Sikhism - The Review of Religions". Al Islam. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "A Gurdwara steeped in history". The Times of India. 25 Mar 2012.

- ^ The Sikh Review, Volume 41, Issues 469–480. Sikh Cultural Centre. 1993. p. 14.

انظر أيضاً

وصلات خارجية

| سبقه — |

گورو السيخ 20 August 1507 – 7 September 1539 |

تبعه گورو أنگد |

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-roman"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-roman"/>

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "note"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="note"/>

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles having same image on Wikidata and Wikipedia

- Articles containing Punjabi-language text

- Articles containing هندي-language text

- Articles containing أردو-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from January 2021

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from May 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2023

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة from May 2023

- مواليد 1469

- وفيات 1539

- ثوريون

- گوروات السيخ

- مؤسسو أديان

- 15th-century religious leaders

- 15th-century Indian philosophers

- Founders of religions

- Miracle workers

- People from Nankana Sahib District

- Indian Sikh religious leaders

- Guru Nanak Dev