منشأة الإشعال الوطنية

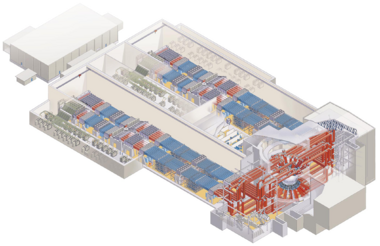

منشأة الإشعال الوطنية (إنگليزية: National Ignition Facility، اختصاراً NIF)، هو جهاز أبحاث ضخم، مبني على الليزر- اندماج القصور الذاتي (ICF)، يقع في مختبر لورانس ليڤرمور الوطنى في ليڤرمور، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة. مهمة المنشأة هي تحقيق الاشعال الاندماجي مع اكتساب الطاقة. حققت أول تجربة انصهار علمية التعادل في 5 ديسمبر 2022، مع زيادة في الطاقة قدرها 1.5 ميگا جول.[1][2] تدعم المنشأة صيانة الأسلحة النووية والتصميم من خلال دراسة سلوك المادة في ظل الظروف الموجودة في التفجيرات النووية.[3]

منشأة الإشعال الوطنية هي أكبر وأقوى جهاز اندماج بحصر القصور الذاتي (ICF) تم تصنيعه حتى الآن.[4] يتمثل المفهوم الأساسي لـ ICF في ضغط كمية صغيرة من الوقود للوصول إلى الضغط ودرجة الحرارة اللازمة للاندماج. تحتوي منشأة الإشعال الوطنية على أكثر تقنيات الليزر نشاطًا في العالم. يسخن الليزر الطبقة الخارجية من كرة صغيرة. الطاقة مكثفة لدرجة أنها تتسبب في انفجار الكرة من الداخل، مما يؤدي إلى الضغط على الوقود بداخلها. يصل الانفجار الداخلي إلى سرعته القصوى البالغة 350 كم/ث،[5] رافعاً كثافة الوقود من كثافة الماء تقريباً إلى حوالي 100 ضعف كثافة الرصاص. يؤدي توصيل الطاقة والعملية الكظومة أثناء الانفجار الداخلي إلى ارتفاع درجة حرارة الوقود إلى مئات الملايين من الدرجات. في درجات الحرارة هذه، تحدث عمليات الاندماج في فترة زمنية صغيرة جدًا قبل انفجار الوقود للخارج.

بدأ إنشاء منشأة الإشعال الوطنية عام 1997. واكتملت متأخرة عن موعدها المحدد بخمس سنوات وبتكلفة أربعة أضعاف ميزانيتها الأصلية. اعتمدت المنشأة في 31 مارس 2009، من قبل وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية.[6] عُقدت أولى التجارب واسعة النطاق في يونيو 2009[7] واُعلن عن اكتمال أول "تجربة اشعال متكاملة" (التي اختبرت قوة الليزر) في أكتوبر 2010.[8]

التجارب من 2009 حتى 2012 كانت تُعقد تحت "حملة الإشعال الوطنية"، بهدف الوصول للإشعال قبل وصول الليزر لطاقته الكاملة، في وقت ما في منتصف عام 2012. انتهت الحملة رسمياً في سبتمبر 2012، عند الوصول لحوالي 1⁄10 الحالات اللازمة للإشعال.[9][10] بعد ذلك، استخدمت منشأة الإشعال الوطنية بشكل أساسي لعلوم المواد وأبحاث الأسلحة. عام 2021، بعد التحسينات في تصميم هدف الوقود، أنتجت منشأة الإشعال الوطنية 70% من طاقة الليزر، متجاوزة الرقم القياسي المسجل عام 1997 بواسطة مفاعل JET البالغ 67% وحققت حرق الپلازما. في 5 ديسمبر 2022، بعد مزيد من التحسينات التقنية، وصلت منشأة الإشعال الوطنية إلى "الإشعال"، أو التعادل العلمي، لأول مرة، محققة عائد طاقة بنسبة 154%.[11]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أساسيات الاندماج بالحبس القصوري

تستخدم أجهزة الاندماج بحصر القصور الذاتي (ICF) طاقة هائلة للتسخين السريع للطبقات الخارجية من هدفٍ لكي تضغطه. في القنبلة الهيدروجينية، يتوفر ذلك من خلال متفجر انشطار نووي. في الأجهزة غير الانشطارية، فإن مصادر الطاقة تشم آشعة الليزر والجسيمات.[12]

الهدف هو بلية كروية صغيرة تحتوي بضعة مليگرامات من الوقود الاندماجي، الذي يكون في المعتاد مزيج من الديوتريوم (D) والتريتيوم (T)، لأن ذلك الخليط له أقل درجة حرارة إشعال.[12]

الطاقة من الليزر تؤدى إلى ارتفاع درجات الحرارة على سطح كرية في البلازما ، والتي تفجر السطح من وقود الهيدروجين . الجزء المتبقى من الهدف يندفع إلى الداخل, ضغط في نهاية المطاف إلى نقطة صغيرة من كثافة عالية للغاية. و blowoff السريع يخلق أيضا موجة الصدمة التى تسافر نحو مركز وقود مضغوط من جميع الجوانب. عندما يصل إلى مركز الوقود، فإن حجما صغيرا يسخن ويحدث له إنضغاط إلى حد كبير. وعندما ترتفع درجة الحرارة والكثافة لتلك البقعة الصغيرة بدرجة عالية بما فيه الكفاية، فإنه سوف تحدث تفاعلات الاندماج وإطلاق الطاقة.[13]

ردود الفعل للإندماج والافراج عن جزئيات ذات طاقة عالية، والبعض منها، في المقام الأول جسيم ألفا تتصادم مع وقود عالي الكثافة والحرارة المحيطة بها أكثر من ذلك. إذا كانت هذه العملية تحمل ما يكفي من الطاقة في منطقة معينة يمكن أن يسبب ذلك الوقود للخضوع للإندماج كذلك. ونظرا للظروف حق الشامل للكثافة عالية في استهلاك الوقود ما يكفي من الضغط ودرجة الحرارة، فإن عملية التسخين تلك تؤدي إلى سلسلة من ردود الفعل، وحرق نحو الخارج من مركز حيث بدأت موجة صدمة رد الفعل. هذا هو الشرط المعروف باسم "اشتعال"، الأمر الذي سيؤدي إلى نسبة كبيرة من الوقود في الهدف يمر بالإندماج وإطلاق كميات كبيرة من الطاقة.[14]

اعتبارًا من عام 1998 ، استخدمت معظم تجارب الاندماج بحصر القصور الذاتي محركات الليزر. فُحصت محركات أخر ، مثل الأيونات الثقيلة المدفوعة بواسطة معجلات الجسيمات.[15][16]

التصميم

النظام

اعتبارًا من عام 2004، استخدمت منشأة الإشعال الوطنية طريقة التشغيل غير المباشرة، حيث يقوم الليزر بتسخين أسطوانة معدنية صغيرة تحيط بالكبسولة بداخلها. تسبب الحرارة، المعروفة باسم هولورام (hohlraum) (تعني بالألمانية "الغرفة المجوفة" أو التجويف)، في إعادة إصدار الطاقة من الاسطوانة بتردد أشعة سينية أعلى، والتي لا تزال أكثر توازناً موزعة ومتناظرة. أثبتت الأنظمة التجريبية، بما في ذلك أوميگا ونوڤا، صحة هذا النهج.[17] تدعم الطاقة العالية لمنشأة الإشعال الوطنية هدفاً أكبر بكثير؛ يبلغ قطر تصميم الحبيبات الأساسي حوالي 2 مم. يتم تبريدها إلى حوالي 18 كلڤن (−255 °س) وتُبطن ببطبقة من وقود الديوتيريوم والتريتيوم المجمد (DT). يحتوي الجزء الداخلي المجوف على كمية صغيرة من غاز الديوتيريوم والتريتيوم.[18]

في تجربة نموذجية، يولد الليزر 3 م.ج. من طاقة ليزر الأشعة تحت الحمراء لـ4 محتملة. قد يتبقى حوالي 1.5 م.ج بعد التحويل إلى الأشعة فوق البنفسجية، وتفقد 15% أخرى في الهولورام. حوالي 15 بالمائة من الأشعة السينية الناتجة، حوالي 150 ك.ج، تمتصها الطبقات الخارجية للهدف.[19] يكون الاقتران بين الكبسولة والأشعة السينية ضائعًا، وفي النهاية يتم ترسيب حوالي 10 إلى 14 كيلو جول من الطاقة في الوقود.[20]

يتم ضغط الوقود الموجود في مركز الهدف بكثافة تبلغ حوالي 1.000 g/سم3.[21] للمقارنة، تبلغ كثافة الرصاص حوالي 11 گ/سم3).الضغط يعادل 300 مليار جو.[22]

بناءاً على عملية المحاكاة، كان من المتوقع[when?] إطلاق حوالي 20 م.ج. من طاقة الاندماج، مما يؤدي للحصول على طاقة اندماج صافية، مشار لها بالحرف Q، من حوالي 15 (طاقة اندماج خارجة/طاقة ليزر الأشعة فوق البنفسجية داخلة).[19] من المتوقع أن تؤدي التحسينات في كل من نظام الليزر وتصميم الهولورام إلى تحسين الطاقة التي تمتصها الكبسولة إلى حوالي 420 ك.ج. (وبالتالي ربما 40 إلى 50 في الوقود نفسه)، والتي بدورها يمكن أن تولد ما يصل إلى 100-150 م.ج. لطاقة الاندماج.[21] يسمح التصميم الأساسي بإطلاق طاقة إندماج مقدارها 45 م.ج. بحد أقصى، بسبب تصميم غرفة الهدف.[23] يعادل هذا انفجار حوالي 11 كج تي إن تي.[24]

اعتباراً من 1996، كانت الطاقة المنتجة أقل من 400 م.ج.[25] من الطاقة في مكثفات النظام التي تشغل مضخمات الليزر. ستكون الكفاءة الصافية wall-plug لمنشأة الإشعال الوطنية (طاقة ليزر الأشعة فوق البنفسجية مقسومة على الطاقة المطلوبة لضخ أشعة الليزر من مصدر خارجي) أقل من واحد بالمائة، وستكون الكفاءة الإجمالية من الجدار إلى الانصهار أقل من 10% في أحسن الأحوال. لكي تكون مفيدة لإنتاج الطاقة، يجب أن يكون ناتج الاندماج على الأقل أكبر من هذه الطاقة المدخلة.

Commercial laser fusion systems would use much more efficient diode-pumped solid state lasers، حيث تم إثبات كفاءة توصيل الجدار بنسبة 10 بالمائة، وكان من المتوقع أن تتراوح نسبة الكفاءات بين 16 و18 في المائة مع وجود مفاهيم متقدمة قيد التطوير عام 1996.[26]

الليزر

اعتبارًا من عام 2010، كانت منشأة الإشعال الوطنية تهدف إلى تخليق وميض ذروته 500 تيراواط (TW) من الضوء يصل إلى الهدف من اتجاهات عديدة في غضون بضع پيكو ثانية. يستخدم التصميم 192 شعاعًا في نظام متوازي من أشعة الليزر التي يتم ضخها بمصباح يدوي، neodymium-doped phosphate glass lasers.[27]

To ensure that the output of the beamlines is uniform, the laser is amplified from a single source in the Injection Laser System (ILS). This starts with a low-power flash of 1053-nanometer (nm) infrared light generated in an ytterbium-doped optical fiber laser termed Master Oscillator.[28] Its light is split and directed into 48 Preamplifier Modules (PAMs). Each PAM conducts a two-stage amplification process via xenon flash lamps. The first stage is a regenerative amplifier in which the pulse circulates 30 to 60 times, increasing its energy from nanojoules to tens of millijoules. The second stage sends the light four times through a circuit containing a neodymium glass amplifier similar to (but much smaller than) the ones used in the main beamlines, boosting the millijoules to about 6 joules. According to LLNL, designing the PAMs was one of the major challenges. Subsequent improvements allowed them to surpass their initial design goals.[29]

The main amplification takes place in a series of glass amplifiers located at one end of the beamlines. Before firing, the amplifiers are first optically pumped by a total of 7,680 flash lamps. The lamps are powered by a capacitor bank that stores 400 MJ (110 kWh). When the wavefront passes through them, the amplifiers release some of the energy stored in them into the beam. The beams are sent through the main amplifier four times, using an optical switch located in a mirrored cavity. These amplifiers boost the original 6 J to a nominal 4 MJ.[13] Given the time scale of a few nanoseconds, the peak UV power delivered to the target reaches 500 TW.[30]

Near the center of each beamline, and taking up the majority of the total length, are spatial filters. These consist of long tubes with small telescopes at the end that focus the beam to a tiny point in the center of the tube, where a mask cuts off any stray light outside the focal point. The filters ensure that the beam image is extremely uniform. Spatial filters were a major step forward. They were introduced in the Cyclops laser, an earlier LLNL experiment.[31]

The end-to-end length of the path the laser beam travels, including switches, is about 1,500 metres (4,900 ft). The various optical elements in the beamlines are generally packaged into Line Replaceable Units (LRUs), standardized boxes about the size of a vending machine that can be dropped out of the beamline for replacement from below.[32]

After amplification is complete the light is switched back into the beamline, where it runs to the far end of the building to the target chamber. The target chamber is a 10-metre-diameter (33 ft) multi-piece steel sphere weighing 130,000 kilograms (290,000 lb).[33] Just before reaching the target chamber, the light is reflected off mirrors in the switchyard and target area in order to hit the target from different directions. Since the path length from the Master Oscillator to the target is different for each beamline, optics are used to delay the light in order to ensure that they all reach the center within a few picoseconds of each other.[34]

One of the last steps before reaching the target chamber is to convert the infrared (IR) light at 1053 nm into the ultraviolet (UV) at 351 nm in a device known as a frequency converter.[35] These are made of thin sheets (about 1 cm thick) cut from a single crystal of potassium dihydrogen phosphate. When the 1053 nm (IR) light passes through the first of two of these sheets, frequency addition converts a large fraction of the light into 527 nm light (green). On passing through the second sheet, frequency combination converts much of the 527 nm light and the remaining 1053 nm light into 351 nm (UV) light. Infrared (IR) light is much less effective than UV at heating the targets, because IR couples more strongly with hot electrons that absorb a considerable amount of energy and interfere with compression. The conversion process can reach peak efficiencies of about 80 percent for a laser pulse that has a flat temporal shape, but the temporal shape needed for ignition varies significantly over the duration of the pulse. The actual conversion process is about 50 percent efficient, reducing delivered energy to a nominal 1.8 MJ.[36]

As of 2010, one important aspect of any ICF research project was ensuring that experiments could be carried out on a timely basis. Previous devices generally had to cool down for many hours to allow the flashlamps and laser glass to regain their shapes after firing (due to thermal expansion), limiting their use to one or fewer firings per day. One of the goals for NIF has been to reduce this time to less than four hours, in order to allow 700 firings a year.[37]

Other concepts

NIF is also exploring new types of targets. Previous experiments generally used plastic ablators, typically polystyrene (CH). NIF targets are constructed by coating a plastic form with a layer of sputtered beryllium or beryllium–copper alloy, and then oxidizing the plastic out of the center.[38][39] Beryllium targets offer higher implosion efficiencies from x-ray inputs.[40]

Although NIF was primarily designed as an indirect drive device, the energy in the laser as of 2008 was high enough to be used as a direct drive system, where the laser shines directly on the target without conversion to x-rays. The power delivered by NIF UV rays was estimated to be more than enough to cause ignition, allowing fusion energy gains of about 40x, somewhat higher than the indirect drive system.[41]

As of 2005, scaled implosions on the OMEGA laser and computer simulations showed NIF to be capable of ignition using a polar direct drive (PDD) configuration where the target was irradiated directly by the laser only from the top and bottom, without changes to the NIF beamline layout.[42]

As of 2005, other targets, called saturn targets, were specifically designed to reduce the anisotropy and improve the implosion.[43] They feature a small plastic ring around the "equator" of the target, which becomes a plasma when hit by the laser. Some of the laser light is refracted through this plasma back towards the equator of the target, evening out the heating. NIF ignition with gains of just over thirty-five times are thought to be possible, producing results almost as good as the fully symmetric direct drive approach.[42]

التاريخ

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

العمليات

تراكم التجارب الرئيسية

حملة الإشعال الوطنية

تقرير وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية، يوليو 2012

فشل الإشعال، تحولات التركيز، انتهاء لايف

مزاعم التعادل

تجارب المخزون

استمرار تجارب الإشعال

مشروعات مماثلة

بعض المشروعات المماثلة:

انظر أيضاً

معرض الصور

الهوامش

المصادر

- ^ Clery, Daniel (December 13, 2022). "With historic explosion, a long sought fusion breakthrough". Science (in الإنجليزية). doi:10.1126/science.adg2803. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ David Kramer (December 13, 2022), "National Ignition Facility surpasses long-awaited fusion milestone", Physics Today (American Institute of Physics) 2022 (2): 1213a, doi:, https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.2.20221213a/full/, "The shot at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory on 5 December is the first-ever controlled fusion reaction to produce an energy gain."

- ^ "About NIF & Photon Science" Archived ديسمبر 2, 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- ^ Hogan, W.J; Moses, E.I; Warner, B.E; Sorem, M.S; Soures, J.M (2001). "The National Ignition Facility". Nuclear Fusion. 41 (5): 567–573. doi:10.1088/0029-5515/41/5/309. ISSN 0029-5515.

- ^ Nathan, Stuart. "Tracing the sources of nuclear fusion". The Engineer.

- ^ "Department of Energy Announces Completion of World's Largest Laser". United States Department of Energy. March 31, 2009. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ "First NIF Shots Fired to Hohlraum Targets". National Ignition Facility. June 2009. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ "First successful integrated experiment at National Ignition Facility announced". General Physics. PhysOrg.com. October 8, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ قالب:Cite techreport

- ^ An Assessment of the Prospects for Inertial Fusion Energy. National Academies Press. July 2013. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-309-27224-7.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةigntion2022-llnl - ^ أ ب Winterberg, Friedwardt (2010) (in en), The Release of Thermonuclear Energy by Inertial Confinement: Ways Towards Ignition, World Scientific, p. 2, ISBN 978-981-4295-90-1

- ^ أ ب "How NIF works", Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Retrieved on October 2, 2007.

- ^ Per F. Peterson, "Inertial Fusion Energy: A Tutorial on the Technology and Economics", University of California, Berkeley, 1998. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ Per F. Peterson, "How IFE Targets Work", University of California, Berkeley, 1998. Retrieved on May 8, 2008. Archived مايو 6, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Per F. Peterson, "Drivers for Inertial Fusion Energy", University of California, Berkeley, 1998. Retrieved on May 8, 2008. Archived مايو 6, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ J.D. Lindl et al., The physics basis for ignition using indirect-drive targets on the National Ignition Facility, Physics of Plasmas, Vol. 11, February 2004, page 339. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ Biello, David. "High-Powered Lasers Deliver Fusion Energy Breakthrough". Scientific American.

- ^ أ ب Suter, L.; J. Rothenberg, D. Munro, et al., "Feasibility of High Yield/High Gain NIF Capsules[dead link]", Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, December 6, 1999. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ Hurricane, O. A.; Callahan, D. A.; Casey, D. T.; Dewald, E. L.; Dittrich, T. R.; Döppner, T.; Barrios Garcia, M. A.; Hinkel, D. E.; Berzak Hopkins, L. F.; Kervin, P.; Kline, J. L.; Pape, S. Le; Ma, T.; MacPhee, A. G.; Milovich, J. L.; Moody, J.; Pak, A. E.; Patel, P. K.; Park, H.-S.; Remington, B. A.; Robey, H. F.; Salmonson, J. D.; Springer, P. T.; Tommasini, R.; Benedetti, L. R.; Caggiano, J. A.; Celliers, P.; Cerjan, C.; Dylla-Spears, R.; Edgell, D.; Edwards, M. J.; Fittinghoff, D.; Grim, G. P.; Guler, N.; Izumi, N.; Frenje, J. A.; Gatu Johnson, M.; Haan, S.; Hatarik, R.; Herrmann, H.; Khan, S.; Knauer, J.; Kozioziemski, B. J.; Kritcher, A. L.; Kyrala, G.; Maclaren, S. A.; Merrill, F. E.; Michel, P.; Ralph, J.; Ross, J. S.; Rygg, J. R.; Schneider, M. B.; Spears, B. K.; Widmann, K.; Yeamans, C. B. (May 2014). "The high-foot implosion campaign on the National Ignition Facility". Physics of Plasmas. 21 (5): 056314. Bibcode:2014PhPl...21e6314H. doi:10.1063/1.4874330. OSTI 1129989.

- ^ أ ب Lindl, John (September 24, 2005). "Ignition Physics Program" (PDF). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2006. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhurricane - ^ M. Tobin et al., Target Area Design Basis and System Performance for NIF, American Nuclear Society, June 1994. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ "Table megajoules to tons of TNT | MJ to tTNT". www.qtransform.com.

- ^ "NIF By the Numbers" (PDF). LLNL. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Paine, Stephen; Marshall, Christopher (September 1996). "Taking Lasers Beyond the NIF". Science and Technology Review.

- ^ "Press release: NNSA and LLNL announce first successful integrated experiment at NIF". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (in الإنجليزية). October 6, 2010.

- ^ P.J. Wisoff et al., NIF Injection Laser System Archived سبتمبر 8, 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Proceedings of SPIE Vol. 5341, pages 146–155

- ^ Keeping Laser Development on Target for the NIF Archived ديسمبر 4, 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Retrieved on October 2, 2007

- ^ Hunt, J.T.; Manes, K.R.; Murray, J.R.; Renard, P.A.; Sawicki, R.; Trenholme, J.B.; Williams, W. (November 16, 1994). "Laser Design Basis for the National Ignition Facility". Fusion Technology. 26 (3P2): 767–771. doi:10.13182/FST94-A40247 – via DOI.org (Crossref).

- ^ "45 Years of Laser Leadership". lasers.llnl.gov.

- ^ Larson, Doug W. (2004). "NIF laser line-replaceable units (LRUs)". In Lane, Monya A; Wuest, Craig R (eds.). Optical Engineering at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory II: The National Ignition Facility. Vol. 5341. p. 127. Bibcode:2004SPIE.5341..127L. doi:10.1117/12.538467. S2CID 122364719.

- ^ Lyons, Daniel (November 14, 2009). "Could This Lump Power the Planet?". Newsweek. p. 3. Archived from the original on November 17, 2009. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Arnie Heller, Orchestrating the World's Most Powerful Laser Archived نوفمبر 21, 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Science & Technology Review, July/August 2005. Retrieved on May 7, 2008

- ^ P.J. Wegner et al.,NIF final optics system: frequency conversion and beam conditioning Archived سبتمبر 8, 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Proceedings of SPIE 5341, May 2004, pages 180–189.

- ^ Bibeau, Camille; Paul J. Wegner, Ruth Hawley-Fedder (June 1, 2006). "UV SOURCES: World's largest laser to generate powerful ultraviolet beams". Laser Focus World. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ NIF Project Sets Record for Laser Performance Archived مايو 28, 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, June 5, 2003. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ Wilson, Douglas C.; Bradley, Paul A.; Hoffman, Nelson M.; Swenson, Fritz J.; Smitherman, David P.; Chrien, Robert E.; Margevicius, Robert W.; Thoma, D. J.; Foreman, Larry R.; Hoffer, James K.; Goldman, S. Robert; Caldwell, Stephen E.; Dittrich, Thomas R.; Haan, Steven W.; Marinak, Michael M.; Pollaine, Stephen M.; Sanchez, Jorge J. (May 1998). "The development and advantages of beryllium capsules for the National Ignition Facility". Physics of Plasmas. 5 (5): 1953–1959. Bibcode:1998PhPl....5.1953W. doi:10.1063/1.872865.

- ^ "Meeting the Target Challenge". Science & Technology Review. Archived from the original on November 15, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ^ Wilson, D. C.; Yi, S. A.; Simakov, A. N.; Kline, J. L.; Kyrala, G. A.; Dewald, E. L.; Tommasini, R.; Ralph, J. E.; Olson, R. E.; Strozzi, D. J.; Celliers, P. M.; Schneider, M. B.; MacPhee, A. G.; Zylstra, A. B.; Callahan, D. A.; Hurricane, O. A.; Milovich, J. L.; Hinkel, D. E.; Rygg, J. R.; Rinderknecht, H. G.; Sio, H.; Perry, T. S.; Batha, S. "X-ray drive of beryllium capsule implosions at the National Ignition Facility". Journal of Physics: Conference Series (in الإنجليزية). 717. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/717/1/012058. ISSN 1742-6588.

- ^ S. V. Weber et al., Hydrodynamic Stability of NIF Direct Drive Capsules Archived ديسمبر 13, 2022 at the Wayback Machine, MIXED session, November 8. Retrieved on May 7, 2008.

- ^ أ ب Yaakobi, B.; R. L. McCrory, S. Skupsky, et al. Polar Direct Drive—Ignition at 1 MJ, LLE Review, Vol 104, September 2005, pp. 186–8. Retrieved on May 7, 2008 Archived يناير 2, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ True, M. A.; J. R. Albritton, and E. A. Williams, "The Saturn Target for Polar Direct Drive on the National Ignition Facility, LLE Review, Vol. 102, January–March 2005, pp. 61–6. Retrieved on May 7, 2008. Archived أغسطس 29, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "HiPER". LMF Project. 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "HiPER". HiPER Project. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ^ "Dry-Run Experiments Verify Key Aspect of Nuclear Fusion Concept: Scientific 'Break-Even' or Better Is Near-Term Goal". Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Shenguang-II High Power Laser". Chinese Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

وصلات خارجية

- "National Ignition Facility: How NIF Works, NIF & Photon Science". 2010-05-27. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- "Lasers, Photonics, and Fusion Science: Science and Technology on a Mission". lasers.llnl.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- "NIF Director, Dr Ed Moses, on the progress of the facility". Ingenia. December 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- "NIF project director Moses says facility is ready to go". spie.org. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- EST, Newsweek Staff On 11/13/09 at 7:00 PM (2009-11-13). "Inside Livermore Lab's Race to Invent Clean Energy". Newsweek (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-12-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - eric. "NIF Laser Fusion in Fulldome" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- CleryNov. 23, Daniel; 2020; Am, 10:45 (2020-11-23). "Laser fusion reactor approaches 'burning plasma' milestone". Science | AAAS (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-12-05.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Articles with dead external links from December 2022

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Vague or ambiguous time from December 2022

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: numeric name

- مراكز أبحاث نووية

- ليزر أبحاث اندماج القصور الذاتي

- Nuclear stockpile stewardship

- معاهد أبحاث في الولايات المتحدة

- منشآت وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية

- معمل لورنس ليڤرمور الوطني

- مشاريع هندسية

- ليڤرمور، كاليفورنيا