معاداة الصين في الولايات المتحدة

Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States began in the 19th century, shortly after Chinese immigrants first arrived in North America,[1] and continues into the 21st century. It has taken many forms throughout history, including prejudice, racist immigration restrictions, murder, bullying, massacre, and other acts of violence. Anti-Chinese sentiment and violence in the country first manifested in the 1860s, when Chinese people were employed in the building of the world's first transcontinental railroad. Its origins can be traced partly to competition with white people for jobs[2] and reports of Americans who had lived and worked in China and wrote relentlessly negative and unsubstantiated reports of locals.

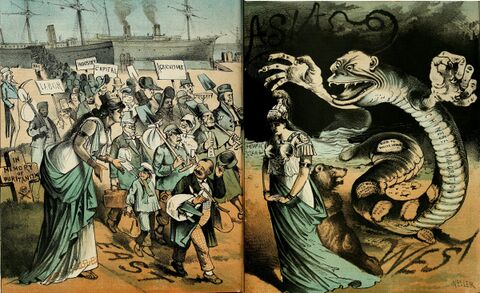

Violence against Chinese in California, Oregon, Washington, and throughout the country took many forms, including pogroms; expulsions, including the destruction of a Chinatown in Denver; and massacres such as the Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871, the Rock Springs massacre, and the Hells Canyon Massacre.[3][4][5] Anti-Chinese sentiment led to the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned the naturalization and further immigration of people of Chinese descent. Amid discussions of "Yellow Peril", anti-Chinese sentiment was eventually extended to all Asians, leading to the broader Asian Exclusion Act of 1924.[6]

Although relations between the US and China normalized after the Sino-Soviet split and the 1972 visit by Richard Nixon to China, anti-Chinese sentiment has increased in the United States since the end of the Cold War, especially since the 2010s, and its increase has been attributed to China's rise as a superpower, which is perceived as a primary threat to America's position as the world's sole superpower.[7][8][9] Since 2019, xenophobia and racism further intensified due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which was first reported in the Chinese city of Wuhan, with increased discrimination, racism, and violence against Chinese people, people of Chinese descent or anyone perceived to be Chinese, especially Asians.[10][11][12][13][14] According to survey results released on 27 April 2023 based on 6,500 respondents, nearly 75% of Chinese Americans have experienced racism in the past twelve months with 7% having suffered property destruction, 9% physical assault or intimidation, 20% verbal or online harassment, and 46% unequal treatment.[15]

Early Chinese immigration to the United States

The arrival of three Chinese seamen in Baltimore in 1785 marked the first record of Chinese people in the United States. Starting with the California Gold Rush in the middle 19th century, the United States — particularly the West Coast states — enlisted large numbers of Chinese migrant laborers. Early Chinese immigrants worked as gold miners, and later on subsequent large labor projects, such as the building of the first transcontinental railroad. The decline of the Qing Dynasty in China, instability and poverty caused many Chinese, especially from the province of Guangdong, to emigrate overseas in search of a more stable life, and this coincided with the rapid growth of American industry. Chinese people were considered by employers as "reliable" workers who would continue working, without complaint, even under destitute conditions.[16]

Chinese migrant workers encountered considerable prejudice in the United States, especially by the people who occupied the lower layers in white society, and Chinese "coolies" were used as a scapegoat for depressed wage levels by politicians and labor leaders.[2] Cases in which Chinese people were physically assaulted include the Chinese massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles and the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit. The 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel in New York, for which a Chinese person was suspected, was blamed on the entire Chinese community and led to physical violence. "The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States."[17]

The emerging American trade unions, under such leaders as Samuel Gompers, also took an outspoken anti-Chinese position,[18] regarding Chinese laborers as competitors to white laborers. Only with the emergence of the international trade union Industrial Workers of the World did trade unionists start to accept Chinese workers as part of the American working-class.[19]

During this period, the phrase "yellow peril" was popularized in the U.S. by newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst.[20] It was also the title of a popular book by an influential U.S. religious figure, G. G. Rupert, who published The Yellow Peril; or, Orient vs. Occident in 1911. Based on the phrase "the kings from the East" in the Christian scriptural verse Revelation 16:12,[21] Rupert made the claim that China, India, Japan and Korea were attacking the West, but that Jesus Christ would stop them.[22] In his 1982 book The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American fiction, 1850–1940, William F. Wu states that "Pulp magazines in the 30s had a lot of yellow peril characters loosely based on Fu Manchu... Most were of Chinese descent, but because of the geopolitics at the time, a growing number of people were seeing Japan as a threat, too."[23]

In the western states, "Anti-Chinese Leagues" were formed in cities such as Tombstone, Arizona,[24][25] San Francisco,[26] and Santa Rosa, California.[27] Anti-Chinese riots, expulsions and massacres broke out in several western localities: Los Angeles, CA (1871), San Francisco, CA (1877), Denver, CO (1880), Eureka, CA (1885), Rock Springs, WY (1885), Tacoma, WA (1885), Seattle, WA (1886), Chinese Massacre Cove, OR (1887).

Chinese Exclusion Act and legal discrimination

In 1862, the Anti-Coolie Act specifically taxed Chinese immigrants at rates over half their income to suppress their jobs and economic participation per yellow peril tropes popular at that time.

In the 1870s and 1880s, various legal discriminatory measures were taken against Chinese people. A notable example is that after San Francisco segregated its Chinese school children from 1859 until 1870, the law was amended in 1870 so the requirement to educate Chinese children could be dropped entirely. The amendment of the law led to Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473 (1885), a landmark court case in the California Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the exclusion of a Chinese American student, Mary Tape, from public school based on her ancestry was unlawful. However, the legislation was passed at the urging of the San Francisco Superintendent of Schools Andrew J. Moulder after the school board lost its case and a segregated school was established.

Another key piece of legislation was the Naturalization Act of 1870, which extended citizenship rights to African Americans but barred Chinese from naturalization on the grounds that they and other Asians could not be assimilated into American society. Unable to become citizens, Chinese immigrants were prohibited from voting and serving on juries, and dozens of states passed alien land laws that prohibited non-citizens from purchasing real estate, thus preventing them from establishing permanent homes and businesses. The idea of an "unassimilable" race became a common argument in the exclusionary movement against Chinese Americans. In particular, even in his lone dissent against Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), then-Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote of Chinese people as: "a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race."[29]

In 1873, the Pigtail Ordinance targeted Qing dynasty immigrants' largely mandatory queue hairstyle which intended to reduce Qing immigration by banning their hairstyle which they must have to enable customary later re-entry to China. The city board passed it but the mayor vetoed it. The city council enacted it in 1876 but was struck down as unconstitutional in 1879.

In the US, xenophobic fear of the alleged "Yellow Peril" led to the implementation of the Page Act of 1875 which excluded Chinese women from entering the US per yellow peril and dragon lady stereotypes,[30] the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, expanded ten years later by the Geary Act which required Chinese to register and secure a certificate as proof of entry at risk of deportation or hard labor, removed Chinese as witnesses in court proceedings, and removed Chinese as recipients of habeas corpus in legal proceedings. The Immigration Act of 1917 then created an "Asian Barred Zone" under nativist influence.

The 1879 Constitution of the State of California prohibited the employment of Chinese people by state and local governments, as well as by businesses which were incorporated in California. Also, it delegated the power to remove Chinese people to the local governments of California.[31][32]

In 1880, the elected officials of the city of San Francisco passed an ordinance which made it illegal to operate a laundry in a wooden building without a permit from the Board of Supervisors. The ordinance delegated the power to grant or withhold the permits upon the Board of Supervisors. At the time, about 95% of the city's 320 laundries were operated in wooden buildings. Approximately two-thirds of those laundries were owned by Chinese people. Although most of the city's wooden building laundry owners applied for a permit, only one permit was granted of the two hundred applications from any Chinese owner, while virtually all non-Chinese applicants were granted a permit.[33][34] However, this led to the 1886 Supreme Court case Yick Wo v. Hopkins, that was the first case where the Supreme Court ruled that a law that is race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[35]

Discriminatory laws, in particular the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were aimed at restricting further immigration from China.[36] It was the first law to racially exclude persons and leave them intentionally unprotected by law. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed by the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943. The Chinese Exclusion Act allowed limited college students entry into the US, however, it became increasingly difficult for such immigrants to gain access. By 1900, laws restricted Chinese students from entering the country unless they came from a wealthy family, they sought studies in programs not offered in China, and required a return to China after completing their studies.[37] Heavy discrimination against Chinese students made it difficult for the US to expand international education opportunities in China and limited the ability of US colleges and universities from improving the reputation of their institutions.

In the USA xenophobic fears against the alleged "Yellow Peril" led to the implementation of the Page Act of 1875 which excluded Chinese women from entering the US per yellow peril and dragon lady stereotypes,[30] the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, expanded ten years later by the Geary Act . The Immigration Act of 1917 then created an "Asian Barred Zone" under nativist influence. It eliminated all immigration from all of geographical Asia. The Chinese Exclusion Act was one of the most significant restrictions on free immigration in U.S. history. The Act excluded Chinese "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining" from entering the country for ten years under penalty of imprisonment and deportation. Many Chinese were relentlessly beaten just because of their race.[38][39] The few Chinese non-laborers who wished to immigrate had to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to immigrate, which tended to be difficult to prove.[39]

The 1921 Emergency Quota Act then the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration according to national origins. While the Emergency Quota Act used the census of 1910, xenophobic fears in the WASP community lead to the adoption of the 1890 census, more favorable to White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) population, for the uses of the Immigration Act of 1924, which responded to rising immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as Asia.

In 1922, the Cable Act added the forfeiture of an American woman's citizenship if she lived abroad with a foreigner spouse, racially excluded Americans from naturalizing if married to a foreign husband, required women living in the United States to retain their citizenship in other words to not marry foreigners, and ensured no procedures for Americans living abroad who had lost one's citizenship prior to 1922 to repatriate back to the US. Its 1930 amendments later removed these anti-immigrant clauses.

In 1927, the Supreme Court held in Lum v. Rice that Mississippi could require a Chinese child to attend the local school for Black students since she was not white under that state's law. The unanimous opinion by Chief Justice, and former president, William Howard Taft held that racial segregation in public education did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment, allowing such discrimination to become much more widespread until the later Brown v. Board of Education decision held it all unconstitutional.

In 1929, the National Origins Formula explicitly kept the status quo distribution of ethnicity by allocating quotas in proportion to the actual population. The idea was that immigration would not be allowed to change the "national character". Total annual immigration was capped at 150,000. Asians were excluded but residents of nations in the Americas were not restricted, thus making official the racial discrimination in immigration laws. This system was repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

In 1943, the Magnuson Act allowed 105 Chinese immigrants annually, itself an extension of the Immigration Act of 1924 and further intentionally miscalculated downwards and explicitly continued bans against Chinese immigrants' property-ownership rights both by law or de facto until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 repealed the such.

Chinese labor and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

According to statistics, between 1820 and 1840, only 11 Chinese people emigrated to the United States. However, many Chinese were living in distress due to the end of the Qing Dynasty. The United States offered a more stable life, thanks to the gold rush in California, the construction of railways, and the resulting large demand for labor. Beginning in 1848, many Chinese chose to immigrate to the US. California Governor John McDougal in 1851 praised Chinese people as "the most valuable immigrants" to California.[40]

In order to recruit more laborers, the United States and China signed the Burlingame Treaty in 1868.[41] The Burlingame Treaty provided several rights, including that Chinese people can freely enter and leave the United States; the right of abode in the United States; and the United States most-favored treatment of Chinese nationals in the United States. The Treaty stimulated immigration for the 20 years between 1853 and 1873, and resulted in the immigration of nearly 105,000 Chinese to the United States by 1880.[42]

1882 was an election year in California. In order to secure more votes, California politicians adopted a staunch anti-China stance. In Congress, California Republican Senator John Miller spoke at length in support of a bill to prohibit further Chinese immigrants, substantially the same as one from the prior session of Congress that had been vetoed by Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes. Senator Miller submitted a motion to ban the immigration Chinese laborers for 20 years, citing the passage of the 1879 anti-Chinese referendums in California and Nevada by huge margins as proof of popular support.[43] The motion was discussed in the Senate over the next eight days. All the Senators from western states and most of the southern Democratic Party supported Miller's proposal, strenuously objected to the eastern states senator. After intense debate, the motion eventually passed the Senate by a vote of 29 of 15; it would go on to pass in the House of Representatives on March 23, by 167 votes to 66 votes (55 abstentions).[42]

President Chester A. Arthur vetoed the bill on April 4, 1882, as it violated the provisions of the Angell Treaty, which restricted but did not ban immigration from China. Congress was unable to overturn the veto, and passed a version of the bill that banned immigration for ten years in lieu of the original twenty-year ban. On May 6, 1882, Miller's proposal was signed by President Arthur, and became the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.[42]

Amendments introduced during the debate over the bill prohibited the naturalization of Chinese immigrants.[42][44] After the initial ten-year ban in the Chinese Exclusion Act ended, Chinese exclusion was extended in 1892 by the Geary Act and then made permanent in 1902.[44]

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 shifted Americans' fears of the Yellow Peril from China to Japan.[45]

Cold War

Anti-Chinese sentiment during the Cold War was largely the result of the Red Scare and McCarthyism, which coincided with increased popular fear of communist espionage because of the Chinese Civil War and China's involvement in the Korean War.[46] During the era, suspected Communists were imprisoned by the hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand of them lost their jobs.[46] Many of those who were imprisoned, lost their jobs or were questioned by committees, had a real past or present connection of some kind with the Communist Party. However, for the vast majority of them, their potential to do harm to the nation and the nature of their communist affiliations were both tenuous.[47] Among these victims were Chinese Americans, who are often viewed with suspicion of being affiliated with the CCP.

Deportation of Qian Xuesen

The most notable example is that of the top Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen. Allegations were made that he was a communist, and his security clearance was revoked in June 1950.[48] The Federal Bureau of Investigation located an American Communist Party document from 1938 with his name on it, and used it as justification for the revocation. Without his clearance, Qian found himself unable to pursue his career, and within two weeks, he announced plans to return to mainland China, which had come under the government of Mao Zedong. The Undersecretary of the Navy at the time, Dan A. Kimball, tried to keep Qian in the US:

It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a Communist than I was, and we forced him to go.[49]

Qian would spend the next five years under house arrest, which included constant surveillance with the permission to teach without any research (classified) duties.[48] Caltech appointed attorney Grant Cooper to defend Qian. In 1955, the United States deported him to China in exchange for five American pilots captured during the Korean War. Later, he became the father of the modern Chinese space program.[50][51][52]

21st century

Modern anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States may originate from American fears of China's role as a rising geopolitical power. Perceptions of China's geopolitical rise on the world stage have been so prevalent that the 'rise of China' has been named the top news story of the 21st century by the Global Language Monitor, as measured by number of appearances in the global print and electronic media, on the Internet and blogosphere, and in Social Media.[53]

During the United States 2010 elections, a significant number[54] of negative advertisements were ran by both major American political parties that focused on a candidates' alleged support for free trade with China. Some of the stock images that accompanied ominous voiceovers about China were actually of Chinatown, San Francisco.[55] In particular, an advertisement called "Chinese Professor", which portrays a 2030 conquest of the West by China, used local Asian American extras to play Chinese, but the actors were not informed of the nature of the shoot.[56] Columnist Jeff Yang said that in the campaign there was a "blurry line between Chinese and Chinese-Americans."[55] Larry McCarthy, the producer of "Chinese Professor," defended his work by saying that "this ad is about America, it's not about China."[57] Other editorials commenting on the video have called the video not anti-Chinese.[54][57][58]

Wolf Amendment

As component of the Wolf Amendment, many American space researchers were prohibited from working with Chinese citizens affiliated with a Chinese state enterprise or entity.[59] In April 2011, the 112th United States Congress banned NASA from using its funds to host Chinese visitors at NASA facilities because of espionage concerns.[60] Earlier in 2010, US Representative John Culberson, had urged President Barack Obama not to allow further contact between NASA and the China National Space Administration (CNSA).[61][62]

Donald Trump's campaign and presidency

2016 presidential campaign

In November 2015, Donald Trump promised to designate China as a currency manipulator on his first day in office.[63] He pledged "swift, robust and unequivocal" action against Chinese piracy, counterfeit American goods, and the theft of American trade secrets and intellectual property. He also condemned China's "illegal export subsidies and lax labor and environmental standards."[63]

In January 2016, Trump proposed a 45% tariff on Chinese exports to the United States to give "American workers a level playing field."[64][65] When asked about potential Chinese retaliation to the implementation of tariffs, such as sales of US bonds, Trump judged such a scenario to be unlikely: "They won't crash our currency. They will crash their economy. That's what they are going to do if they start playing that."[66] In a May 2016 speech, Trump responded to concerns regarding a potential trade war with China: "We're losing $500 billion in trade with China. Who the hell cares if there's a trade war?"[67] Trump also said in May 2016 that China is "raping" the U.S. with free trade.[68]

Presidency (2017–21)

In January 2018, Trump launched a trade war with China and he also began to impose new visa restrictions on foreign students and visiting scholars of Chinese nationality;[69][70] many affected said that they experienced delays in renewing their visas or even outright cancellations of their visas.[71][72][69] In 2018, Presidential Advisor Stephen Miller proposed banning all Chinese nationals from obtaining visas to study in the United States.[73][74][75]

According to the results of a Gallup poll which were published in February 2019, China was considered the greatest enemy of the United States by 21% percent of American respondents, only second to Russia.[76]

In April 2019, FBI Director Christopher Wray said that China posed a "whole of a society threat".[69][77] In May 2019, Director of Policy Planning Kiron Skinner said that China "is the first great power competitor of the US that is not caucasian."[78][79][80]

The current deterioration of relations has led to a spike in anti-Chinese sentiment in the US.[81][82] According to a Pew Research Center poll released in August 2019, 60 percent of Americans have negative opinions about China, with only 26 percent holding positive views. The same poll found that China was named as America's greatest enemy by 24 percent of respondents in US, tied along with Russia.[83]

In March 2020, Trump referred to the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States as the "Chinese Virus", despite the fact that in February 2020, the World Health Organization strongly advised the public not to racially profile the SARS‑CoV‑2 coronavirus as the "Chinese virus" or the "Wuhan virus".[84][85][86][87] Additionally, the racist terms "Wuflu" and "Kung Flu" emerged in the United States during this period as pejorative and xenophobic ways of referring to COVID-19. These terms are linked to Wuhan, where the virus was first detected, or China in general, via portmanteau with terms from traditional Chinese Martial Arts, Wushu and Kung Fu, and have been used by President Trump and members of his administration in an official capacity.[88][89] Use of these terms has drawn widespread criticism for their perceived racial insensitivity.[90]

In May 2020, a West Virginia-raised Chinese-American CBS reporter, Weijia Jiang, questioned Trump at a White House coronavirus briefing about his stance on testing and he told her to question China. The reporter responded to Trump by asking him why he singled her out by stating that she should question China, which led to an abrupt end to the briefing.[91][92]

On July 23, 2020, then-United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced the end of what he called "blind engagement" with the Chinese government. He also criticized Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping[93] as "a true believer in a bankrupt totalitarian ideology."[94]

In December 2020, Tennessee Senator Marsha Blackburn tweeted that "China has a 5,000 year history of cheating and stealing. Some things will never change...", resulting in a backlash by Chinese-American civil rights activists, arguing that her tweet insulted people of Chinese descent.[95]

COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic was first reported in the city of Wuhan, Hubei, China, in December 2019, and as a result, acts and displays of Sinophobia, have increasingly occurred, as well as incidents of prejudice, xenophobia, discrimination, violence, and racism against people of East Asian ancestry.[97][98][99] According to a June 2020 Pew Research study, 58% of Asian Americans believe that racist views of them had increased since the pandemic.[100] A study by the New York University College of Arts & Science found that there was no overall increase of Anti-Asian sentiment among the American population, instead it suggested that "already prejudiced persons" had felt authorized by the pandemic to act openly on their prejudices.[101]

Joe Biden's presidency

Since the start of the Biden Presidency in January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden has described tensions with China as a competition between democracy and autocracy. Studies suggest that framing the relationship between the United States and China as a great power competition foments anti-Asian sentiment among White Americans. According to an analysis conducted by Vladimir Enrique and Medenica David Ebner at Asia Times in June 2021, White Americans are more likely to support war with China if such a military confrontation between the two countries ever materializes. White Americans described as "racially resentful" were 36 percentage points more likely than other White Americans to perceive China posing as a major geopolitical threat back in 2012 and 20 percentage points more likely compared in 2016.[102]

A report which was published by Stop AAPI Hate listed 43% of AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) individuals reporting incidents from 2020 to 2022 to be ethnically Chinese. A survey in 2021 found that 49% of AAPIs felt safe going out, 65% felt worried about the safety of family members and elders, 32% of parents were concerned their child would be a victim of anti-AAPI discrimination at school, 95% of Asian Americans who reported a hate incident to Stop AAPI Hate viewed the U.S. as dangerous to them, 98% of Asian elders who experienced hate incidents believed the U.S. has become more physically dangerous for Asians, 49% reported anxiety or depression, and 72% named hate against them as their greatest source of stress.[103]

A national survey estimated that at least three million AAPIs experienced hate incidents between March 2021 and March 2022. According to Stop AAPI Hate, 20% of reported hate incidents involve scapegoating, 96% of scapegoating incidents blame Asians and Asian Americans for the COVID-19 epidemic, 4% for national security reasons such as spying for the Chinese Communist Party, and 1% for being economic threats. Stop AAPI Hate notes that both Democrats and Republicans use "rhetoric that paints China as an economic threat to America’s existence", mirroring language used in scapegoating East Asians and Asian Americans at large.[104]

A report conducted by Tobita Chow in 2021 used a table to show parallels between the "China threat" narratives and sentiments expressed in anti-Asian incidents such as "China is cheating the US" and "You are a liar, a cheater", or "China is an espionage or influence threat" and "You are a spy, you are CCP". According to Chow, believers of American exceptionalism who perceive American global domination to be at risk of being replaced by a rising and more geopolitically assertive China, exacerbated by global economic problems and weak economic growth, contribute to a sense of anxiety that fosters zero-sum competition between countries. In discussions about China, the two claims that China is a threat to American hegemony and that it is an existential threat to the US and Americans are often used interchangeably regardless of the difference in their plausibility. Chow says that a deep commitment to American exceptionalism can make these two claims identical to each other. Anti-China messaging has been used to build bipartisan support for a number of economic policies that promote investment in infrastructure, research, technology, and job creation as necessary to counter China. Some special interest groups such as the military industrial complex stand to materially benefit from the "China threat" narratives and promote them for that reason. Chow says that "narratives about China can shape popular perceptions of Chinese people" and that the opposite is also true, where narratives of Chinese people also justify perceptions of China.[105]

On 27 April 2023, Columbia University and the Committee of 100 announced the results of a survey on Chinese Americans. According to the survey results based on the answers of 6,500 participants across the US, 74% of Chinese Americans have experienced racism in the past twelve months. One in five reported verbal or online harassment several times in the past twelve months. Nearly half the respondents (46%) reported unequal treatment compared to others. Almost one in ten (9%) reported physical assault or intimidation while 7% reported destruction of property.[15]

According to the 2023 STAATUS Index survey, nearly half of Americans believe that negative views of China have contributed to anti-Asian attacks or incidents. Among the reasons for anti-Asian hate, 33% of respondents believe that viewing China as an economic threat is a contributing factor while 47% believe that viewing China as an espionage threat is a contributing factor.[106]

A research article submitted in September 2022 and published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America in June 2023 states that scholars of Chinese descent feel significant unease in the US: 83% received insults in a non-professional setting in the last year, 72% feel unsafe as a researcher, 35% feel unwelcome in the US, and 61% have considered leaving the US.[107]

Purchase of or acquisition of title to real property

A Texas Senate bill tabled in 2023 by state representatives of the Republican Party, known as SB 147, was met with intense backlash particularly by Asian American groups.[108] The bill would prohibit "certain aliens or foreign entities" from acquiring real property in the state of Texas, including those with affiliations or origins from China.[109] The bill has also found support from Governor of Texas Greg Abbott.[110] Critics have compared the bill to the racist Chinese Exclusion Act and called it unconstitutional.[111][112][113][114] Others also added that it may lead to a negative snowball effect for further racist legislation, particularly targeting Chinese people and East Asians in general.[115]

Sylvester Turner, Mayor of Houston, referred to the bill as "just down right wrong" and that "it is more divisive than anything else".[116] State representative Gene Wu added that "this type of legislation. This growing anti-Asian and anti-immigrant sentiment is a direct attack on our community and on our city, quite frankly."[117] The legislation does not give any exceptions to asylum seekers, lawful permanent residents, valid visa holders or dual citizens.[118] Further protests in the streets of Houston against the bill were held by Asian American groups and allies in February 2023.[118]

Virginia's state Senate, which is controlled by Democrats, also recently passed a ban on land ownership by "foreign adversaries." In all, at least 18 states have considered limiting the ownership of farmland by entities linked to China, according to the National Agricultural Law Center.[119]

On 8 May 2023, Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed bills SB 264 and HB 1355 banning Chinese citizens from buying land in the state. Critics have warned that the bills could contribute to discrimination against the Chinese and other immigrants. Democrat state Rep. Anna V. Eskamani voiced concerns about the impact on Asian Americans. Asian American organizations compared the bills to the Alien Land Laws and the Chinese Exclusion Act.[120][121]

Accusations of spying

Under the Trump administration, the Justice Department launched the China Initiative to target supposed Chinese spies. In 2018, Donald Trump's FBI Director Christopher A. Wray publicly called students and researchers of Chinese descent potential spies and said that the FBI views China "not just a whole-of-government threat but a whole-of-society threat" requiring a "whole-of-society response".

The ACLU said the initiative cast broad, unjustified suspicion on Chinese American scientists and unfairly targeted them for investigation and prosecution. Several of the resulting prosecutions have been based on faulty grounds; they have resulted in devastating consequences for the lives of those affected.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The Biden administration continued the initiative, despite civil-rights organizations' calls to end it. The Asian Americans Advancing Justice expressed "deep concern with the federal government's racial, ethnic, and national origin profiling and discriminatory investigations and prosecutions of Asian Americans and Asian immigrants".[122] A 2021 survey of almost 2,000 scientists in the United States showed that more than half of scientists of Chinese descent, regardless of citizenship, feared surveillance from the US government.[123]

The Justice Department ended the initiative ended on February 22, 2022, citing perceptions of unfair treatment of Chinese Americans and residents of Chinese origin.[124]

Xi Xiaoxing

In 2015, police raided the home of Temple University physics professor Xi Xiaoxing and arrested him at gunpoint in front of his wife and two daughters. The Justice Department (DOJ) accused the scientist of illegally sending trade secrets to China—the design of a pocket heater used in superconductor research—and threatened him with 80 years in prison and $1 million in fines. The scientist's daughter Joyce Xi said, "Newscasters surrounded our home and tried to film through windows. The FBI rummaged through all our belongings and carried off electronics and documents containing many private details of our lives. For months, we lived in fear of FBI intimidation and surveillance. We worried about our safety in public, given that my dad's face was plastered all over the news. My dad was unable to work, and his reputation was shattered."[125]

Temple University forced the professor to take administrative leave and suspended him as chair of the Physics Department. He was also banned from accessing his lab or communicating with his students directly. It was later learned that FBI agents had been listening to his phone calls and reading his emails for months — possibly years.[126]

In 2015, DOJ abruptly dropped the charges after investigators found that the information Xi shared did not include trade secrets.[127]

In 2021, Xi was denied recourse after a Philadelphia court rejected his legal claims for damages.[128]

Hu Anming

In February 2020, University of Tennessee professor Hu Anming was indicted under the China Initiative. He was one of several Chinese-born researchers arrested and accused of failing to disclose their ties with China under the China Initiative.[129]

During Hu's trial in June 2021, an FBI agent admitted to falsely accusing the professor of being a Chinese spy, using baseless information to place him on the federal no-fly list and spying on him and his son for two years. The FBI agent, Kujtim Sadiku, also admitted to using the false information to press Hu to become a spy for the United States government. No evidence was ever discovered that suggested Hu, who is an internationally recognized welding technology expert, had ever spied for China.[130] The defense lawyer argued that Hu was targeted by federal agents determined to find Chinese spies where there were none, and when agents failed to secure an espionage charge, they turned instead to a charge of fraud.[129]

The case was declared a mistrial, raising concerns over whether the Justice Department was over-reaching in its hunt for Chinese spies.[129]

Tang Juan

In September 2020, Chinese cancer researcher Tang Juan was arrested and jailed by U.S. authorities, who accused her of concealing ties to the Chinese military.[131] Tang was denied bail and later placed under house arrest. In 2021, she was released after spending 10 months in jail and house arrest without her case ever making it to trial.[132]

Later, it was revealed that she was not a member of the Chinese military but had only worked as a civilian at a Chinese military facility.[131]

Baimadajie Angwang

Baimadajie Angwang, a police officer for the New York City Police Department (NYPD), was arrested in September 2020 on federal charges of allegedly spying for China.[133] The former Marine subsequently six months in a federal detention center before he was freed on bail while awaiting trial. Abruptly, federal prosecutors would drop the charges against him in January 2021 without further explanation.[133] He was never compensated for his detention and lost his job as a police officer.[133]

See also

- Anti-American sentiment in China

- Anti-Western sentiment in China

- Anti-communism in the United States

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States

- Asian Americans

- Asian American activism

- China–United States relations

- China–United States trade war

- Chinese Americans

- East Asia–United States relations

- History of Asian Americans

- History of Chinese Americans

- History of Japanese Americans

- History of the Republic of China

- History of the People's Republic of China

- Lynching in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Racism in China

- Racism in the United States

- Stereotypes of East Asians in the United States

- Stereotypes of groups within the United States

- Stop AAPI Hate

- Stop Asian Hate

- Xenophobia and racism related to the COVID-19 pandemic#United States

References and notes

- ^ McClain, Charles J. (1994). In search of equality: the Chinese struggle against discrimination in 19th-century America. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08337-7.

- ^ أ ب Kearney, Dennis. ""Our Misery and Despair": Kearney Blasts Chinese Immigration". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "Race riot tore apart Denver's Chinatown". Eugene Register-Guard. October 30, 1996. Retrieved 2020-10-28 – via Google newspapers.

- ^ Gyory, Andrew (1998). Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780807847398. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Grad, Shelby (18 March 2021). "The racist massacre that killed 10% of L.A.'s Chinese population and brought shame to the city". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Guisepi, Robert A. (January 29, 2007). "Asian Americans". World History International. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Art, Robert J (2010). "The United States and the Rise of China: Implications for the Long Haul". Political Science Quarterly. 125 (3): 359–391. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2010.tb00678.x. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 25767046. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Berkeley News; Coronavirus: Fear of Asians rooted in long American history of prejudicial policies, February 12, 2020, https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/02/12/coronavirus-fear-of-asians-rooted-in-long-american-history-of-prejudicial-policies/, retrieved on 20 September 2020, "History is resurfacing again, with China becoming a stronger country and more competitive and a threat to U.S. dominance today, just like Japan was a threat during the Second World War."

- ^ Griffiths, James Griffiths (25 May 2019). "The US won a trade war against Japan. But China is a whole new ball game". CNN. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Reny, Tyler T.; Barreto, Matt A. (28 May 2020). "Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 10 (2): 209–232. doi:10.1080/21565503.2020.1769693. ISSN 2156-5503. S2CID 219749159.

- ^ White, Alexandre I. R. (18 April 2020). "Historical linkages: epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia". The Lancet (in الإنجليزية). 395 (10232): 1250–1251. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30737-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7154503. PMID 32224298.

- ^ Devakumar, Delan; Shannon, Geordan; Bhopal, Sunil S; Abubakar, Ibrahim (April 2020). "Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses". The Lancet. 395 (10231): 1194. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30792-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7146645. PMID 32246915.

- ^ "Many Black, Asian Americans Say They Have Experienced Discrimination Amid Coronavirus". Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Chelsea Daniels, Paul DiMaggio, G. Cristina Mora, Hana Shepherd. "Does Pandemic Threat Stoke Xenophobia?" (PDF). New York University College of Arts & Science. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب "National Survey Data Shows Nearly 3 Out Of Every 4 Chinese Americans Have Experienced Racial Discrimination In The Past 12 Months". May 2, 2023.

- ^ Norton, Henry K. (1924). The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co. pp. 283–296. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Ling, Huping (2004). Chinese St. Louis: From Enclave to Cultural Community. Temple University Press. p. 68.

The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States.

- ^ Gompers, Samuel; Gustadt, Herman (1902). Meat vs. Rice: American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism: Which Shall Survive?. American Federation of Labor.

- ^ Lai, Him Mark; Hsu, Madeline Y. (2010). Chinese American Transnational Politics. University of Illinois Press. pp. 53–54.

- ^ "Foreign News: Again, Yellow Peril". Time. September 11, 1933. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Revelation 16:12 (New King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- ^ "NYU's "Archivist of the Yellow Peril" Exhibit". Boas Blog. August 19, 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- ^ Katayama, Lisa (August 29, 2008). "The Yellow Peril, Fu Manchu, and the Ethnic Future". io9. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "US Immigration 1800s". TombstoneTravelTips. Picture Rocks Networking. April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Hoptown Chinese Section 1879". Historical Marker Database.

- ^ Bernhardt, Jeff (April 28, 1886). "THE ANTI-CHINESE LEAGUE". Daily Alta California. Vol. 40, no. 13393.

- ^ Elliott, Jeff (June 6, 2018). "THE YEAR OF THE ANTI-CHINESE LEAGUE". Santa Rosa History.

- ^ Farwell, Willard B. (1885). The Chinese at home and abroad: together with the Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco on the Condition of the Chinese quarter of that city. San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Co. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Chin, Gabriel J. "Harlan, Chinese and Chinese Americans". University of Dayton Law School. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Ulysses S. Grant, Chinese Immigration, and the Page Act of 1875". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. March 24, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Article XIX of the Constitution of the State of California of 1879 Archived أبريل 26, 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whitman, James (2017) Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780691172422

- ^ only one out of approximately eighty non-Chinese applicants was denied a permit

- ^ "Yick Wo v. Hopkins – Case Brief Summary". www.lawnix.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ 118 الولايات المتحدة 356 (1886). قالب:Usgovpd

- ^ "An Evidentiary Timeline on the History of Sacramento's Chinatown: 1882 – American Sinophobia, The Chinese Exclusion Act and "The Driving Out"". Friends of the Yee Fow Museum, Sacramento, California. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Moon, Krystyn R. (May 2018). "Immigration Restrictions and International Education: Early Tensions in the Pacific Northwest, 1890s–1910s". History of Education Quarterly. 58 (2): 261–294. doi:10.1017/heq.2018.2. S2CID 150233388.

- ^ "Exclusion". Library of Congress. September 1, 2003. Archived from the original on August 10, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "The People's Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". US News. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007.

- ^ Chen, An (2012). "On the Source, Essence of "Yellow Peril" Doctrine and Its Latest Hegemony "Variant" – the "China Threat" Doctrine: From the Perspective of Historical Mainstream of Sino-Foreign Economic Interactions and Their Inherent Jurisprudential Principles" (PDF). The Journal of World Investment & Trade. 13: 1–58. doi:10.1163/221190012X621526. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Schrecker, John (March 2010). ""For the Equality of Men - For the Equality of Nations": Anson Burlingame and China's First Embassy to the United States, 1868". Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 17 (1): 9–34. doi:10.1163/187656110X523717. Alternate URL Archived يونيو 19, 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت ث Chin, Philip (January 2013). "The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882". Chinese American Forum. 28 (3): 8–13. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018. Direct URLs: Part 1 Archived سبتمبر 12, 2015 at the Wayback Machine Part 2 Archived سبتمبر 12, 2015 at the Wayback Machine Part 3 Archived سبتمبر 12, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Senator Miller's Great Anti-Chinese Speech". Daily Alta California. March 1, 1882. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Primary Documents in American History: Chinese Exclusion Act". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Lyman, Stanford M. (Summer 2000). "The "Yellow Peril" Mystique: Origins and Vicissitudes of a Racist Discourse". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. Springer. 13 (4): 699. doi:10.1023/A:1022931309651. JSTOR 20020056. S2CID 141218786.

- ^ أ ب Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. p. xiii. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

- ^ Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown. p. 4. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

- ^ أ ب "Tsien Hsue-Shen Dies". November 2, 2009. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Perrett, B. (January 7, 2008), Sea Change, Aviation Week and Space Technology, Vol. 168, No. 1, pp. 57–61.

- ^ "Meet the US-trained scientist who was deported to China, and became a national hero". Pri.org. February 6, 2017. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Qian Xuesen, Father of China's Space Program, Dies at 98". The New York Times. November 3, 2009. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ "Qian Xuesen dies at 98; rocket scientist helped establish Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Los Angeles Times. September 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ "21世纪新闻排行中国崛起居首位" (in الصينية). Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ أ ب Chi, Frank (November 8, 2010). "In campaign ads, China is fair game; Chinese-Americans are not". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ أ ب Lyden, Jacki (October 27, 2010). "Critics Say Political Ads Hint Of Xenophobia". NPR. Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ Yang, Jeff (October 27, 2010). "Politicians Play The China Card". Tell Me More. NPR. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ أ ب Smith, Ben (October 22, 2010). "Behind The Chinese Professor". Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Fallows, James (October 21, 2010). "The Phenomenal Chinese Professor Ad". Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Ian Sample. "US scientists boycott Nasa conference over China ban". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ Seitz, Virginia (September 11, 2011), "Memorandum Opinion for the General Counsel, Office of Science and Technology Policy", Office of Legal Counsel 35, https://www.justice.gov/olc/2011/conduct-diplomacy.pdf, retrieved on May 23, 2012

- ^ Culberson, John. "Bolden to Beijing?". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ "NASA chief to visit China". AFP. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ أ ب Doug Palmer & Ben Schreckinger, Trump's trade views vows to declare China a currency manipulator on Day One Archived مارس 7, 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Politico (November 10, 2015).

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (January 7, 2016) Donald Trump Says He Favors Big Tariffs on Chinese Exports Archived يوليو 21, 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times.

- ^ Appelaum, Binyamin (March 10, 2016) On Trade, Donald Trump Breaks With 200 Years of Economic Orthodoxy Archived سبتمبر 25, 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times.

- ^ "Donald Trump on the trade deficit with China". Fox News. February 11, 2016. Archived from the original on May 30, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Trump: 'Who the hell cares if there's a trade war?'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ "China accused of trade 'rape' by Donald Trump". BBC News. May 2, 2016. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت Perlez, Jane (April 14, 2019). "F.B.I. Bars Some China Scholars From Visiting U.S. Over Spying Fears". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Yoon-Hendricks, Alexandra (July 25, 2018). "Visa Restrictions for Chinese Students Alarm Academia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "Chinese students in limbo as wait for US visas stretches for months". The Straits Times. April 2, 2019. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "Visas Are The Newest Weapon In U.S.-China Rivalry". NPR. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "US considered ban on student visas for Chinese nationals". Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Adams, Susan. "Stephen Miller Tried To End Visas For Chinese Students". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Fang, Tianyu. "The Man Who Took China to Space". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "Majority of Americans Now Consider Russia a Critical Threat". Gallup.com. February 27, 2019. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "China 'determined to steal up economic ladder at US' expense': FBI chief". South China Morning Post. April 27, 2019. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Panda, Ankit. "A Civilizational Clash Isn't the Way to Frame US Competition With China". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "Were US official's 'clash of civilisations' remarks a slip or something else?". South China Morning Post. May 25, 2019. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Musgrave, Paul. "The Slip That Revealed the Real Trump Doctrine". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (July 20, 2019). "A New Red Scare Is Reshaping Washington". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Caught in the middle: Chinese-Americans feel heat as tensions flare". South China Morning Post. September 25, 2018. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Views of China Amid Trade War Turn Sharply Negative". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. August 13, 2019. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Wu, Nicholas. "GOP senator says China 'to blame' for coronavirus spread because of 'culture where people eat bats and snakes and dogs'". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ Forgey, Quint. "Trump on 'Chinese virus' label: 'It's not racist at all'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Fischer, Sara (March 17, 2020). "The WHO said to stop calling it "Chinese" coronavirus, but Republicans didn't listen". Axios. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ Filipovic, Jill (March 18, 2020). "Trump's malicious use of 'Chinese virus'". CNN. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ "Pompeo calls for united 'message' after reportedly pushing G-7 members to call it 'Wuhan virus'". Fox News. March 25, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "Trump doubles down on 'China virus,' demands to know who in White House used phrase 'Kung Flu'". Fox News. March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ "A last, desperate pivot: Trump and his allies go full racist on coronavirus". Salon. March 19, 2020. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ Choi, David. "'Why are you saying that to me': Chinese American reporter calls Trump out on his anti-China remarks and suggests he's singling her out". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Ellison, Sarah; Izadi, Elahe (May 12, 2020). "Trump's 'ask China' response to CBS's Weijia Jiang shocked the room — and was part of a pattern". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Churchill, Owen (July 25, 2020). "US officials now call Xi Jinping 'general secretary' instead of China's 'president' – but why?". South China Morning Post. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Re, Gregg (July 23, 2020). "Pompeo announces end of 'blind engagement' with communist China: 'Distrust but verify'". Fox News. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Chinese Americans protesting Sen. Marsha Blackburn Archived يناير 28, 2021 at the Wayback Machine News 4 Nashville. December 12, 2020

- ^ O'Hara, Mary Emily. "Mock Subway Posters Urge New Yorkers to Curb Anti-Asian Hate". www.adweek.com. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Reny, Tyler T.; Barreto, Matt A. (May 28, 2020). "Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 10 (2): 209–232. doi:10.1080/21565503.2020.1769693. S2CID 219749159.

- ^ White, Alexandre I. R. (April 18, 2020). "Historical linkages: epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia". The Lancet. 395 (10232): 1250–1251. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30737-6. PMC 7154503. PMID 32224298.

- ^ Devakumar, Delan; Shannon, Geordan; Bhopal, Sunil S; Abubakar, Ibrahim (April 2020). "Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses". The Lancet. 395 (10231): 1194. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30792-3. PMC 7146645. PMID 32246915.

- ^ "Many Black, Asian Americans Say They Have Experienced Discrimination Amid Coronavirus". Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project. July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Daniels, Chelsea; DiMaggio, Paul; Mora, G. Cristina; Shepherd, Hana. "Does Pandemic Threat Stoke Xenophobia?" (PDF). New York University College of Arts & Science. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "White Americans more likely to support war with China". June 17, 2021.

- ^ Stop AAPI Hate Year 2 Report stopaapihate.org July 2022

- ^ Stop AAPI Hate Scapegoating Report stopaapihate.org October 2022

- ^ Anti Asian Racism Report 2021 peoplesaction.org June 2021

- ^ "STAATUS Index 2023: Attitudes towards Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders" (PDF).

- ^ https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2216248120

- ^ Choi, Hojun (January 29, 2023). "Chinese Americans gather in downtown Dallas to oppose 'hateful' state Senate bills". Dallas News. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Rep. Lois Kolkhorst (R); Rep. Mayes Middleton (R). "Texas Legislature Online – 88(R) History for SB 147". capitol.texas.gov. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Ashley (January 23, 2023). "Local, state officials condemn proposed bill that forbids people, businesses from certain countries from owning Texas land". Houston Public Media. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Mizan, Nusaiba (January 30, 2023). "'It's about human rights': Rally at Capitol protests Senate proposal to ban land purchases". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; يناير 31, 2023 suggested (help) - ^ Yu, Leo (January 24, 2023). "Banning Chinese from buying land has a racist past". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Liebelson, Dana (February 8, 2023). "A bill banning Chinese citizens from buying property has some wondering if they're welcome in Texas". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Ruiz, Anayeli (January 23, 2023). "'This is just a bad bill' | Houston city leaders join in protest against SB 147". khou.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Dunbar, Betty; Ko, Andrew; Barth, Marshall (February 14, 2023). "Will Texas' anti-Asian legislation bring back racist housing covenants?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Brittany (January 23, 2023). "Mayor Turner joins voices condemning SB 147, legislation called 'racist' that aims to ban citizens, businesses from China, Iran, North Korea, Russia from purchasing land in Texas". KPRC. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Turner, Re'Chelle (February 11, 2023). "Asian American community members and elected officials speak out against Senate Bill 147". KPRC. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ أ ب Venkatraman, Sakshi (February 16, 2023). "Chinese citizens in Texas are incensed over a proposal to ban them from buying property in the state". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Anstey, Chris (March 11, 2023). "America's Anti-China Restrictions Are Going Local". Bloomberg.

- ^ Oladipo, Gloria (May 9, 2023). "DeSantis signs bills banning Chinese citizens from buying land in Florida". The Guardian.

- ^ "Bill banning Chinese from owning land in Florida passes in the House". May 6, 2023.

- ^ "Letter to President-elect Biden Re the China Initiative" (PDF). Asian Americans Advancing Justice. January 5, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ German, Michael; Liang, Alex (January 3, 2022). "Why Ending the Justice Department’s “China Initiative” is Vital to U.S. Security". justsecurity.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh (February 23, 2022). "DOJ shuts down China-focused anti-espionage program". Politico. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ "The FBI wrongly accused my father of spying for China. Government has a role in anti-Asian violence". USA Today.

- ^ "ACLU News & Commentary". American Civil Liberties Union.

- ^ Johnson, Kevin (September 11, 2015). "Justice Dept. drops charges against Temple physicist". USA Today. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "US judge tosses claims by Chinese-born professor over arrest". Associated Press. April 20, 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Yong, Charissa (June 17, 2021). "Mistrial declared in US case of Tennessee scientist accused of hiding China work". The Straits Times.

- ^ Satterfield, Jamie (June 13, 2021). "Trial reveals federal agents falsely accused a UT professor born in China of spying". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ أ ب Fromer, Jacob (August 29, 2020). "Chinese scientist Tang Juan to be released on bail". South China Morning Post.

- ^ "US seeks to drop charge against researcher accused of hiding ties to PLA". July 23, 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت O’Brien, Rebecca Davis (February 10, 2023). "Can a Police Officer Accused of Spying for China Ever Clear His Name?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

Further reading

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 الصينية-language sources (zh)

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2023

- Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

- Asian-American issues

- Bullying in the United States

- Asian-American-related controversies

- Anti-Chinese sentiment by country

- Anti-Chinese violence in the United States

- Articles containing video clips

- China–United States relations

- Racially motivated violence against Asian-Americans

- Xenophobia

- White supremacy in the United States