لو هاڤر

Le Havre

Lé Hâvre (Norman) | |

|---|---|

Subprefecture and commune | |

| الإحداثيات: 49°29′N 0°06′E / 49.49°N 0.10°E | |

| البلد | فرنسا |

| المنطقة | نورماندي |

| الإقليم | السين البحري |

| الدائرة | Le Havre |

| الكانتون | Le Havre-1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 |

| بينالتجمعات | Le Havre Seine Métropole |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة (2020–2026) | Édouard Philippe[1] (Horizons) |

| المساحة 1 | 46٫95 كم² (18٫13 ميل²) |

| • الحضر (2017) | 194٫9 كم² (75٫3 ميل²) |

| • العمران (2017) | 678٫4 كم² (261٫9 ميل²) |

| التعداد (يناير 2019) | 168٬290 |

| • الترتيب | 15th in France |

| • الكثافة | 3٬600/km2 (9٬300/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2017[2]) | 235٬218 |

| • الكثافة الحضرية | 1٬200/km2 (3٬100/sq mi) |

| • العمرانية (2017[2]) | 326٬865 |

| • الكثافة العمرانية | 480/km2 (1٬200/sq mi) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/الرمز البريدي | 76351 /76600, 76610, 76620 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.lehavre.fr |

| |

| موقع تراث عالمي لليونسكو | |

| Official name | Le Havre, the City Rebuilt by Auguste Perret |

| السمات | Cultural: ii, iv |

| مراجع | 1181 |

| التدوين | 2005 (29 Session) |

| المساحة | 133 ha |

| منطقة عازلة | 114 ha |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

لو هاڤر ( Le Havre ؛ /lə ˈhɑːv(rə)/,[3][4][5] بالفرنسية: [lə ɑvʁ(ə)] (![]() استمع)؛ Norman: Lé Hâvre) هي مدينة تقع في نورماندي، شمال غرب فرنسا، وتطل على القنال الإنگليزي، وبالقرب من السين. حسب إحصاء السكان لعام 1999، بلغ عدد سكان المدينة 190905 نسمة. كانت المدينة الأكبر في النورماندي قبل روان. وهي الآن ثاني أكبر ميناء مصدر في الجمهورية الفرنسية. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very close to the Prime Meridian. Le Havre is the most populous commune of Upper Normandy, although the total population of the greater Le Havre conurbation is smaller than that of Rouen. After Reims, it is also the second largest subprefecture in France. The name Le Havre means "the harbour" or "the port". Its inhabitants are known as Havrais or Havraises.[6]

استمع)؛ Norman: Lé Hâvre) هي مدينة تقع في نورماندي، شمال غرب فرنسا، وتطل على القنال الإنگليزي، وبالقرب من السين. حسب إحصاء السكان لعام 1999، بلغ عدد سكان المدينة 190905 نسمة. كانت المدينة الأكبر في النورماندي قبل روان. وهي الآن ثاني أكبر ميناء مصدر في الجمهورية الفرنسية. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very close to the Prime Meridian. Le Havre is the most populous commune of Upper Normandy, although the total population of the greater Le Havre conurbation is smaller than that of Rouen. After Reims, it is also the second largest subprefecture in France. The name Le Havre means "the harbour" or "the port". Its inhabitants are known as Havrais or Havraises.[6]

The city and port were founded by King Francis I in 1517. Economic development in the early modern period was hampered by religious wars, conflicts with the English, epidemics, and storms. It was from the end of the 18th century that Le Havre started growing and the port took off first with the slave trade then other international trade. After the 1944 bombings the firm of Auguste Perret began to rebuild the city in concrete. The oil, chemical, and automotive industries were dynamic during the Trente Glorieuses (postwar boom) but the 1970s marked the end of the golden age of ocean liners and the beginning of the economic crisis: the population declined, unemployment increased and remains at a high level today.

Changes in years 1990–2000 were numerous. The right won the municipal elections and committed the city to the path of reconversion, seeking to develop the service sector and new industries (aeronautics, wind turbines). The Port 2000 project increased the container capacity to compete with ports of northern Europe, transformed the southern districts of the city, and ocean liners returned. Modern Le Havre remains deeply influenced by its employment and maritime traditions. Its port is the second largest in France, after that of Marseille, for total traffic, and the largest French container port.

In 2005, UNESCO inscribed the central city of Le Havre as a World Heritage Site because of its unique post-WWII reconstruction and architecture.[7] The André Malraux Modern Art Museum is the second of France for the number of impressionist paintings. The city has been awarded two flowers by the National Council of Towns and Villages in Bloom in the Competition of Cities and Villages in Bloom.[8]

تأسست المدينة عام 1517، وكان اسمها "لو هافر دو گراس". صنفت المدينة من بين مواقع التراث العالمي منذ يوليو 2005. في المدينة جامعة واحدة، وبها ناد رياضي (نادي لو هاڤر) وهو أقدم أندية كرة القدم الفرنسية.

اسم المكان

The name of the town was attested in 1489, even before it was founded by François I in the form le Hable de Grace then Ville de Grace in 1516, two years before its official founding.[9] The learned and transient name of Franciscopolis in tribute to the same king, is encountered in some documents then that of Havre Marat, referring to Jean-Paul Marat during the French Revolution but was not imposed. However it explains why the complementary determinant -de-Grace was not restored.[9] This qualifier undoubtedly referred to the Chapel of Notre Dame located at the site of the cathedral of the same name. The chapel faced the Chapel Notre Dame de Grace of Honfleur across the estuary.[9] The common noun havre meaning "port" was out of use at the end of the 18th or beginning of the 19th centuries but is still preserved in the phrase havre de paix meaning "safe haven". It is generally considered a loan from Middle Dutch from the 12th century.[10] A Germanic origin can explain the "aspiration" of the initial h. Havre de Grace, Maryland, in the United States retains the "de Grace" from colonial times.

New research however focuses on the fact that the term was attested very early (12th century) and in Norman texts in the forms Hable, hafne, havene, havne, and haule makes a Dutch origin unlikely. By contrast, a Scandinavian etymology is relevant given the old Scandinavian höfn (genitive hafnar) or hafn meaning "natural harbour" or "haven" and the phonetic evolution of the term étrave which is assuredly of Scandinavian origin is also attested in similar forms such as estable and probably dates back to the ancient Scandinavian stafn.[11]

التاريخ

When founded in 1517, the city was named Franciscopolis after Francis I of France. It was subsequently named Le Havre-de-Grâce ("Harbor of Grace"; hence Havre de Grace, Maryland). Its construction was ordered to replace the ancient harbours of Honfleur and Harfleur whose utility had decreased due to silting.

The history of the city is inextricably linked to its harbour. In the 18th century, as trade from the West Indies was added to that of France and Europe, Le Havre began to grow. On 19 November 1793, the city changed its name to Hâvre de Marat and later Hâvre-Marat in honor of the recently deceased Jean-Paul Marat, who was seen as a martyr of the French Revolution. By early 1795, however, Marat's memory had become somewhat tarnished, and on 13 January 1795, Hâvre-Marat changed its name once more to simply Le Havre, its modern name. During the 19th century, it became an industrial center.

At the end of World War I Le Havre played a major role as the transit port used to wind up affairs after the war.[12]

The city was devastated during the Battle of Normandy when 5,000 people were killed and 12,000 homes were totally destroyed before its capture in Operation Astonia. The center was rebuilt in a modernist style by Auguste Perret.

الدروع

|

Current arms of Le Havre. The salamander is the badge of Francis I; the lion is from the Belgian coat of arms; it replaced a fleur-de-lis in 1926 to remember the Belgian government in exile in Le Havre during the First World War). | Gules, a salamander argent crowned or enflamed the same in chief azure three fleurs de lis or cantoned sable with a lion or armed and langued gules. |

|

Arms of Le Havre under the First French Empire | Gules, a salamander argent crowned in Or enflamed the same, in chief azure with 3 mullets of Or quartered azure with a letter N surmounted by a mullet of Or. |

الجغرافيا

الموقع

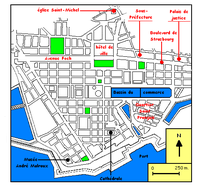

Le Havre is located 50 كيلومتر (31 ميل) west of Rouen on the shore of the English Channel and at the mouth of the Seine. Numerous roads link to Le Havre with the main access roads being the A29 autoroute from Amiens and the A13 autoroute from Paris linking to the A131 autoroute.

Administratively, Le Havre is a commune in the Normandy region in the west of the department of Seine-Maritime. The urban area of Le Havre corresponds roughly to the territory of the Agglomeration community of Le Havre (CODAH)[13] which includes 17 communes and 250,000 people.[14] It occupies the south-western tip of the natural region of Pays de Caux where it is the largest city. Le Havre is sandwiched between the coast of the Channel from south-west to north-west and the estuary of the Seine to the south.

الجيولوجيا والطبوغرافيا

Le Havre belongs to the Paris Basin which was formed in the Mesozoic period. The Paris Basin consists of sedimentary rocks. The commune of Le Havre consists of two areas separated by a natural cliff edge: one part in the lower part of the town to the south including the harbour, the city centre and the suburbs. It was built on former marshland and mudflats that were drained in the 16th century.[16] The soil consists of several metres of alluvium or silt deposited by the Seine.[16] The city centre was rebuilt after the Second World War using a metre of flattened rubble as a foundation.[17][18]

The upper town to the north, is part of the cauchois plateau: the neighbourhood of Dollemard is its highest point (between 90 و 115 متر (295 و 377 أقدام) above sea level). The plateau is covered with a layer of flinty clay and a fertile silt.[19] The bedrock consists of a large thickness of chalk measuring up to 200 m (656 ft) deep.[20] Because of the slope the coast is affected by the risk of landslides.[21]

المناخ

| Month[22] | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg high °C (°F)[22] | 6 (43) |

6 (43) |

8 (47) |

10 (50) |

13 (56) |

16 (61) |

18 (65) |

18 (66) |

17 (63) |

13 (57) |

9 (49) |

7 (45) |

(54) |

| Avg low temperature °C (°F)[22] | 3 (39) |

3 (38) |

5 (42) |

7 (45) |

10 (51) |

12 (55) |

15 (60) |

15 (60) |

13 (57) |

11 (52) |

7 (45) |

5 (41) |

(49) |

Economy

General

Although well developed and diversified, the local economy relies heavily on industrial sites, international groups, and subcontracted SMEs. The Le Havre economy is far from decision centres which are located mainly in Paris and major European economic cities. There is therefore a low representation of head offices in the city with the exception of some local economic successes such as the Sidel Group (now a subsidiary of Tetra Pak) – a distributor of interior furniture, and the ship-owner Delmas which was recently acquired by the CMA-CGM group.

| Name | Commune | Sector |

|---|---|---|

| Renault Sandouville | Sandouville | Automobile |

| Centre Hospitalier Général | Le Havre | Health |

| Le Havre Commune | Le Havre | Administration publique |

| TotalEnergies | Gonfreville | Raffinage |

| Port Authority of Le Havre | Le Havre | Port Services |

| Aircelle | Gonfreville | Aeronautical Construction |

| Total Petrochemicals | Gonfreville | Petrochemicals |

| SNCF | Le Havre | Transport |

| Dresser-Rand | Le Havre | Mechanical Equipment |

| Chevron | Gonfreville | Petrochemicals |

Port

With 68.6 million tons of cargo in 2011, the port of Le Havre is the second largest French seaport in trade volume behind that of Marseille and 50th largest port in the world.[23] It represents 60% of total French container traffic with nearly 2.2 million Twenty-foot equivalent unit|EVP]s in 2011.[24][25] At the European level, it is eighth largest for container traffic and sixth largest for total traffic. The Port receives a large number of oil tankers that transported 27.5 million tonnes of crude oil and 11.7 million tonnes of refined product in 2011.[24] Finally, 340,500 vehicles passed through the Roll-on/roll-off terminal in 2010.[25] 75 regular shipping lines serve 500 ports around the world.[25] The largest trading partner of the port of Le Havre is the Asian continent which alone accounts for 58% of imports by container and 39.6% of exports.[24] The rest of the traffic is distributed mainly to Europe and America.

Le Havre occupies the north bank of the estuary of the Seine on the Channel. Its location is favourable for several reasons: it is on the most frequented waterway in the world; it is the first and last port in the North Range of European ports – the largest in Europe which handles a quarter of all global maritime trade.[26] As a deepwater port, it is accessible to all types of ships whatever their size around the clock.[26] At the national level, Le Havre is 200 كيلومتر (124 mi) west of the most populous and richest region in France: Île-de-France. Since its founding in 1517 on the orders of François I, Le Havre has continued to grow: today it measures 27 km (17 mi) from east to west, about 5 km (3 mi) from north to south with an area of 10،000 هكتار (24،711 acre).[26] The last big project called Port 2000 increased the handling capacity for containers.

The port provides 16,000 direct jobs[25] to the Le Havre region, to which must be added indirect jobs in industry and transport. With approximately 3,000 employees in 2006, the activities of distribution and warehousing provide more jobs,[27] followed by road transport (2,420 jobs) and handling (2,319 jobs).[27]

In 2011, 715,279 passengers passed through the port of Le Havre[24] and there were 95 visits by cruise ships carrying 185,000 passengers.[28] The port expects 110 cuise ship calls in 2012. Created in 1934, the leisure boat harbour of Le Havre is located to the west and is the largest French boat harbour in the Channel with a capacity of 1,160 moorings.[29] Finally, there is a small fishing port in the Saint-François district and a Hawker centre.

Industry

Most industries are located in the industrial-port area north of the estuary and east of the city of Le Havre. The largest industrial employer (2,400 employees[30]) of the Le Havre region is the Renault public company in the commune of Sandouville. The second important sector for the industrial zone is petrochemicals. The Le Havre region has more than a third of French refining capacity. It provides about 50% of the production of basic plastics and 80% of additives and oils[31] with more than 3,500 researchers working in private and public laboratories. Large firms in the chemical industry are mainly in the communes of Le Havre (Millenium Chemicals Le Havre), Montivilliers (TotalEnergies, Yara, Chevron Oronite SA, Lanxess, etc.) and Sandouville (Goodyear Chemicals Europe). A total of 28 industrial establishments manufacture plastics in the Le Havre area many of which are classed as SECESO.[بحاجة لمصدر]

There are several firms in the aerospace industry: SAFRAN Nacelles, a supplier to Airbus, Boeing and other commercial air-framers, making jet engine nacelles and thrust reversers, is located in Harfleur and employs 1,200 people from the Le Havre area.[32] Finally, Dresser-Rand SA manufactures equipment for the oil and gas industry and employs about 700 people.[33] In the energy field, the EDF thermal power plant of Le Havre has an installed capacity of 1,450MW and operates using coal with 357 employees.[34] The AREVA group announced the opening of a factory for building wind turbines: installed in the port of Le Havre, it should create some 1,800 jobs.[35] The machines are designed for Offshore wind power in Brittany, the UK, and Normandy.

Other industries are dispersed throughout the Le Havre agglomeration: the Brûlerie du Havre, which belongs to Legal-Legoût, located in the district of Dollemard that roasts coffee, Sidel located both in the industrial area of Port of Le Havre and Octeville-sur-Mer designs and manufactures blow moulding machines and complete filling line machines for plastic bottles.

Services sector

The two largest employers in the service sector are the Groupe Hospitalier du Havre with 4,384 staff[36] and the City of Le Havre with 3,467 permanent employees.[37] The city has long been home to many service companies whose activity is related to port operations: primarily the ship-owning companies and also the marine insurance companies. The headquarters of Delmas (transport and communications, 1,200 employees) and SPB (Provident Society Banking, insurance, 500 employees) have settled recently at the entrance to the city. The head office of Groupama Transport (300 employees) is also present.

The transport sector is the largest economic sector in Le Havre with 15.5% of employment. Logistics occupies a large part of the population and the ISEL trains engineers in this field. Since September 2007 the ICC has welcomed local students in their first year in the relocated Europe-Asia campus of the Institute of Political Studies of Paris. Higher Education is represented by the University of Le Havre which employs 399 permanent professors and 850 lecturers[38] as well as by engineering companies like Auxitec and SERO.

There are many growth factors in the tourist industry: blue flag rating, World Heritage status from UNESCO, the label French Towns and Lands of Art and History, cruise ship development, a policy of value-creation from heritage, and the City of the Sea project. In January 2020 the city had 26 hotels with a total of 1,428 rooms.[39]

Le Havre is the seat of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Le Havre. It manages the Le Havre Octeville Airport.

Culture

Events and festivals

Le Havre's festival calendar is punctuated by a wide range of events.

In spring a Children's Book Festival was recently created. In May there is the Fest Yves, a Breton festival in the Saint-François district. On the beach of Le Havre and Sainte-Adresse there is a jazz festival called Dixie Days in June. In July, detective novels are featured in the Polar room at the Beach hosted by The Black Anchors. Between the latter also in the context of Z'Estivales is an event offering many shows of street art throughout the summer supplemented by the festival of world music MoZaïques at the fort of Sainte-Adresse in August since 2010. In mid-August there is a Flower parade which passes through the streets of the central city.

In the first weekend of September the marine element is highlighted in the Festival of the Sea. This is a race between Le Havre and Bahia in Brazil. Also every November there is a fair held in the Docks Café. The Autumn Festival in Normandy, organized by the departments of Seine-Maritime and Eure, and the Region of Normandy, runs from September to November and offers numerous concerts throughout the region as well as theatre performances and dance. In late October, since 2009, there is rock music festival which has been at the fort of Tourneville since the moving of the Papa's Production association site there. The West Park Festival, after its inauguration in 2004, has been held in the park of the town hall of Harfleur.

Since 1 June 2006 a Biennale of contemporary Art has been organized by the group Partouche.[40]

Cultural heritage and architecture

Many buildings in the city are classified as "historical monuments", but the 2000s marked the real recognition of Le Havre's architectural heritage. The city received the label "City of Art and History" in 2001, then in 2005 UNESCO inscribed the city of Le Havre as a World Heritage Site.[7]

The oldest building still standing in Le Havre is the Graville Abbey. The other medieval building in the city is the Chapel of Saint-Michel of Ingouville. Because of the bombing in 1944, heritage from the modern era is rare: Le Havre Cathedral, the Church of Saint Francis, the Museum of the Hotel Dubocage of Bleville, the House of the ship-owner and the old palace of justice (now the Natural History Museum) are concentrated in the Notre-Dame and Saint-François areas. The buildings of the 19th century testify to the maritime and military vocations of the city: the Hanging Gardens, the Fort of Tourneville, Vauban docks, and the Maritime Villa. The heritage of the 1950s and 1960s which were the work of the Auguste Perret workshop forms the most coherent architecture: the Church of Saint Francis and the Town Hall are the centrepieces. The all curved architecture of the "Volcano", designed by Oscar Niemeyer, contrasts with that of the rebuilt centre. Finally, the reconstruction of many districts is a showcase for the architecture of the 21st century. Among the achievements by renowned architects are the Chamber of Commerce and Industry (René and Phine Weeke Dottelond), Les Bains Des Docks (Jean Nouvel).[7] °

المناظر الرئيسية

Le Havre was heavily bombed during the Second World War. Many historic buildings were lost as a result.

Literature

Le Havre appears in several literary works as a point of departure to America: in the 18th century, Father Prevost embarked Manon Lescaut and Des Grieux for French Louisiana. Fanny Loviot departed from Le Havre in 1852, as an emigrant to San Francisco and points further west, and recounted her adventures in Les pirates chinois (A Lady's Captivity among Chinese Pirates in the Chinese Seas, 1858).

In the 19th century, Le Havre was the setting for several French novels: Honoré de Balzac described the failure of a Le Havre merchant family in Modeste Mignon. Later, the Norman writer Guy de Maupassant located several of his works at Le Havre such as Au muséum d'histoire naturelle (At the Museum of Natural History) a text published in Le Gaulois on 23 March 1881 and again in Pierre et Jean. Alphonse Allais located his intrigues at Le Havre too. La Bête humaine (The Human Beast) by Émile Zola evokes the world of the railway and runs along the Paris–Le Havre railway. Streets, buildings, and public places in Le Havre pay tribute to other famous Le Havre people from this period: the writer Casimir Delavigne (1793–1843) has a street named after him and a statue in front of the palace of justice alongside another man of letters, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1737–1814).

In the 20th century, Henry Miller located part of the action in Le Havre in his masterpiece Tropic of Cancer, published in 1934. Bouville was the commune where the writer lived who wrote his diary in La Nausée (The Nausea) (1938) by Jean-Paul Sartre who was inspired by Le Havre city where he wrote his first novel. There are also the testimonies of Raymond Queneau (1903–1976), born in Le Havre, the city served as a framework for his novel Un rude hiver (A harsh winter) (1939). The plot of Une maison soufflée aux vents (A house blown to the winds) by Émile Danoën, winner of the Popular Novel Prize in 1951, and its sequel Idylle dans un quartier muré (Idyll in a walled neighbourhood) were located in Le Havre during the Second World War. Under the name Port de Brume Le Havre is the setting for three other novels by this author: Cerfs-volants (Kites), L'Aventure de Noël (The Adventure at Christmas), and La Queue à la pègre (Queue to the underworld). Michel Leiris wrote De la littérature considérée comme une tauromachie (Of literature considered like a bullfight) in December 1945.

Diana Gabaldon set the second novel in her Outlander series, Dragonfly in Amber (1992), partly in Le Havre.

Two mystery novels take place in Le Havre: Le Bilan Maletras (The Maletras Balance) by Georges Simenon and Le Crime de Rouletabille (Crime at the Roulette table) by Gaston Leroux. In Rouge Brésil (Red Brazil), winner of the Goncourt Prize in 2001, Jean-Christophe Rufin describes Le Havre in the 16th century as the port of departure of French expeditions to the New World: the hero Villegagnon leaves of the port to conquer new lands for the French crown which become Brazil. Martine–Marie Muller tells the saga of a clan of Stevedores from Le Havre in the 1950s to the 1970s in Quai des Amériques (Quay of the Americas).

Benoît Duteurtre published in 2001, Le Voyage en France (Travel in France), for which he received the Prix Médicis: the main character, a young American impassioned by France, lands at Le Havre which he describes in the first part of the novel. In 2008, Benoît Duteurtre publishes Les pieds dans l'eau (Feet in the water), a highly autobiographical book in which he describes his youth spent between Le Havre and Étretat. The city hosted writers such as Emile Danoën (1920–1999) who grew up in the district of Saint-François, Yoland Simon (born 1941), and Philippe Huet (born 1955). Canadian poet Octave Crémazie (1827–1879) died at Le Havre and was buried in Saint Marie Cemetery. The playwright Jacques-François Ancelot (1794–1854) was also a native of Le Havre. Two famous historians, Gabriel Monod (1844–1912) and André Siegfried (1875–1959) were from the city.

Le Havre also appears in comic books: for example, in L'Oreille cassée (The Broken Ear) (1937), Tintin embarks on the vessel City of Lyon sailing to South America. The meeting between Tintin and General Alcazar in Les Sept Boules de cristal (The Seven Crystal Balls) (1948) is in Le Havre, according to notes by Hergé in the margins of Le Soir, the first publisher of this adventure. The first adventure of Ric Hochet (1963), the designer Tibet and André-Paul Duchâteau, Traquenard au Havre (Trap at Le Havre) shows the seaside and the port. Similarly, in 1967, for the album Rapt sur le France (Rapt on France), the hero passes by the ocean port. Frank Le Gall, in Novembre toute l'année (November all year) (2000) embarks Theodore Poussin at Le Havre on the Cap Padaran.

Music

Le Havre is the birthplace of many musicians and composers such as Henri Woollett (1864–1936), André Caplet (1878–1925)[41] and Arthur Honegger (1892–1955).[42] There was also Victor Mustel (1815–1890) who was famous for having perfected the harmonium.[43]

Le Havre has long been regarded as one of the cradles of French rock and blues. In the 1980s many groups have emerged after a first dynamic development in the 1960s and 1970s. The most famous personality of Le Havre rock is Little Bob who began his career in the 1970s. The port tradition in many of the groups was repeated in the unused sheds of the port, such as Bovis hall which could hold 20,000 spectators. A blues festival, driven by Jean-François Skrobek, Blues a Gogo existed for eight years from 1995 to 2002. Several artists have been produced such as: Youssou N'Dour, Popa Chubby, Amadou & Mariam, Patrick Verbeke etc. It was organized by the Coup de Bleu association whose former president was head of music Café L'Agora in the Niemeyer Centre which produced the new Le Havre scene. During these same years, the Festival of the Future, the local version of the Fête de l'Humanité (Festival of Humanity), attracted a large audience.

Currently, the musical tradition continues in the Symphony Orchestra of the city of Le Havre, the orchestra of Concerts André Caplet, the conservatory, and music schools such as the Centre for Vocal and Musical Expression (rock) or the JUPO (mainly jazz), associations or labels like Papa's Production (la Folie Ordinaire, Mob's et Travaux, Dominique Comont, Souinq, Your Happy End etc.). The organization by the association of West Park Festival since the 2000s in Harfleur and since 2004 at the Fort of Tourneville is a demonstration. Moreover, since 2008, the association I Love LH was started and promotes Le Havre culture and especially its music scene by organizing original cultural events as well as the free distribution of compilation music by local artists.

Board game

Main articles: Le Havre (board game)

Le Havre is a board game about the development of the town of Le Havre. It was inspired by the games Caylus and Agricola and was developed in December 2007.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Norman language

Main articles: Norman language and Cauchois dialect.

The legacy of the Norman language is present in the language used by the people of Le Havre, part of which is identified as speaking cauchois. Among the Norman words most used in Le Havre there are: boujou (hello, goodbye), clenche (door handle), morveux (veuse) (child), and bezot (te) (last born).

متفرقات

مدن شقيقة

- داليان، الصين

- داليان، الصين - پوان-نوار، جمهورية الكونغو

- پوان-نوار، جمهورية الكونغو - سان پطرسبورگ، روسيا

- سان پطرسبورگ، روسيا - ساوثهامپتون، المملكة المتحدة

- ساوثهامپتون، المملكة المتحدة - تامپا، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة

- تامپا، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة

وصلات خارجية

- الموقع الرسمي

- Visitor center

- Port Authority

- Businesses and craftsmen

- Le Havre on the World Heritage photos

- Pictures of Le Havre. The sultan's elephant in Le Havre on october 2006. Pictures & videos

- Slideshow/Pictures of Le Havre. Town, Niemeyer & Auguste Perret Architecture, portuary zone

المصادر

- ^ "Elections municipales 2020 : Edouard Philippe est officiellement réélu maire du Havre". Franceinfo. 5 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةinsee2017 - ^ "Le Havre". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ قالب:Cite Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ قالب:Cite Merriam-Webster

- ^ "Le nom des habitants du 76 - Seine-Maritime". Habitants.

- ^ أ ب ت "Le Havre, the City Rebuilt by Auguste Perret". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Site officiel du Label Villes et Villages Fleuris". www.villes-et-villages-fleuris.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت François de Beaurepaire (pref. Marianne Mulon), The names of Communes and former parishes of Seine-Maritime, Paris, A. et J. Picard, 1979, 180 p., ISBN 2-7084-0040-1, OCLC 6403150, p. 92-93 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Lexicographic definitions and etymologies of Havre, TLFi, on the CNRTL website (in فرنسية)

- ^ Elisabeth Ridel, The Vikings and the words: The contribution of old Scandinavian to the French language, éditions errance, Paris, 2009, p. 203, 226, 227, 228. (in فرنسية)

- ^ Bullock, Arthur (2009). Gloucestershire Between the Wars: A Memoir. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4793-3. Pages 102-110.

- ^ Rezoning of Urban areas: seeking urban expansion Archived 16 يناير 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Assemblée des Communautés de France, consulted on 19 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Editorial[dead link], CODAH, consulted on 19 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ "Le Havre". Le Havre.

- ^ أ ب Claire Étienne-Steiner, Frédéric Saunier, Le Havre a port with new towns, Paris, éditions du patrimoine, 2005, p. 21 (in فرنسية)

- ^ C. Étienne-Steiner, Le Havre. City, Port, and agglomeration, Rouen, édition du patrimoine, 1999, p. 15 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Isabelle Letélié, Le Havre, unusual itineraries, Louviers, Ysec éditions, 2010, p. 14 (in فرنسية)

- ^ J. Ragot, M. Ragot, Guide to Nature in the Pays de Caux, 2005, p. 6 (in فرنسية)

- ^ P. Auger, G. Granier, The Guide to Pays de Caux, 1993, p. 33 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Information on Nature and scenery in the estuary of the Seine, Carmen, Haute-Normandie, consulted on 19 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ أ ب ت "Weatherbase". Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ World Port ranking 2010, AAPA website, consulted on 27 July 2012

- ^ أ ب ت ث Definitive Statistics 2011[dead link], Port du Havre, consulted on 27 December 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ أ ب ت ث The Port of Le Havre Archived 2 يوليو 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Le Havre développement, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ أ ب ت The Port today Archived 29 أكتوبر 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Grand Port Maritime du Havre, consulted on 28 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ أ ب Employment linked to the Maritime and Port activities in the Le Havre area (excluding industry) Archived 29 أكتوبر 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Port du Havre, consulted on 29 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Laurence Périn, The Cruises in vogue, in Océanes, No. 154, March 2012, p. 6 (in فرنسية)

- ^ The Leisure Boat Port[dead link], Ville du Havre, consulted on 2 August 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Renault/Sandouville Economy: non-working days, Le Figaro, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Petrochemical Chemistry Archived 7 أغسطس 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Le Havre développement, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Aeronautic Archived 7 أغسطس 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Le Havre développement, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Huge contract for Dresser-Rand Le Havre, L'usine nouvelle, 20 July 2007, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ 2011 in brief Archived 1 أكتوبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine, EDF, centrale du Havre, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Océanes Le Havre, No. 156, May 2012, p. 3 (in فرنسية)

- ^ Presentation and key data[dead link], Groupe Hospitalier du Havre, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ The City recruits Archived 1 أغسطس 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Ville du Havre, consulted on 30 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ University of Le Havre data Archived 11 فبراير 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Université du Havre, consulted on 26 July 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcomplet - ^ Cultural Events Archived 10 سبتمبر 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Ville du Havre, consulted on 9 October 2012 (in فرنسية)

- ^ "Caplet, André, Oxford University Press". global.oup.com. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- ^ "Honegger, Arthur, Oxford University Press". global.oup.com. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- ^ "Victor and Auguste Mustel | Harmonium | French". The Metropolitan Museum of Art (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-02-18.

قالب:Seine-Maritime communes قالب:1900 Summer Olympic venues قالب:1924 Summer Olympic venues قالب:Olympic venues sailing

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with فرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Articles with dead external links from July 2018

- Articles with dead external links from December 2017

- Articles with dead external links from December 2021

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Norman-language text

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with image map1 but not image map

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2014

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2019

- لو هاڤ

- مدن فرنسا

- مدن ساحلية

- كوميونات سين-ماريتيم

- مواقع التراث العالمي في فرنسا

- مستوطنات تأسست في 1517

- موانئ فرنسا

- مراكز الدوائر الادارية في فرنسا

- موانئ القنال الإنگليزي

- Populated coastal places in France

- Populated places established in 1517

- Port cities and towns on the French Atlantic coast

- Ports and harbours of the English Channel

- World Heritage Sites in France

- Venues of the 1900 Summer Olympics

- Venues of the 1924 Summer Olympics

- 1517 establishments in France

- صفحات مع الخرائط