كوسكو، پيرو

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

خط زمني لكوسكو

الانتماءات التاريخية مملكة كوسكو, 1197–1438

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

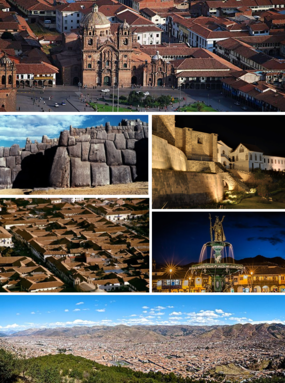

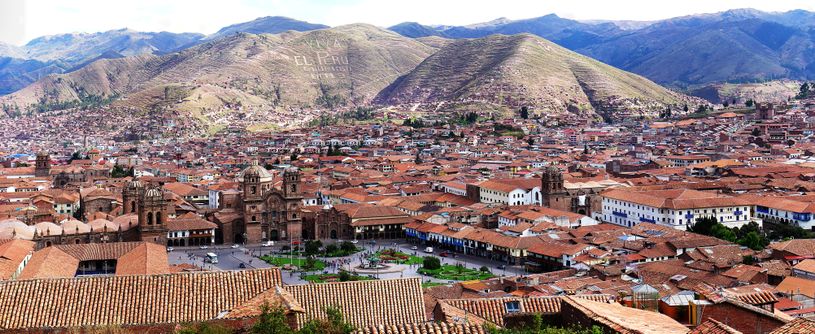

كوسكو (إسپانية: Cuzco النطق الإسپاني: [ˈkusko]; Quechua: Qusqu, Qosqo [ˈqʊsqʊ], [ˈqɔsqɔ])، تُنطق عادة كوزكو ( /ˈkuːskoʊ/)، هي مدينة في جنوب شرق پيرو، بالقرب من وادي أوروبامبا في سلسلة جبال الأنديز. وهي عاصمة منطقة كوسكو ومحافظة كوسكو. عام 2017، كان عدد سكان المدينة 428.450 نسمة. تقع المدينة على الطرف الشرقي لعقدة كوسكو، على ارتفاع 3.400 متر تقريباً.

كان الموقع العاصمة التاريخية لامبراطورية الإنكا من القرن الثالث عشر حتى الفتح الإسپاني في القرن السادس عشر. عام 1983 أعلنت اليونسكو مدينة كوسكو موقعاً للتراث العالمي باسم "مدينة كوسكو". وأصبحت وجهة سياحية رئيسية، حيث تستقبل 2 مليون نسمة سنوياً. حسب دستور پيرو تعد كوسكو العاصمة التاريخية لپيرو.[2]

النُطق والتسمية

الاسم الأصلي للمدينة هو كوسكو Qusqu. على الرغم من أنه كان يستخدم في لغة الكنيتشوا، إلا أن أصوله ترجع إلى لغة الآيمارا. الكلمة مشتقة من عبارة qusqu wanka ('صخرة البومة')، المرتبطة بأسطورة أشقاء أيار الخاصة بتأسيس المدينة. تبعاً لتلك الأسطورة، فقد حصل أيار أواكا على جناحين وطار إلى موقع المدينة المستقبلية؛ وهناك تحول إلى صخرة كعلامة على استيلائه على الأرض عن طريق أيلو ("نسبه"):[3]

بعدها وقف أيار أوتشى، مظهراً زوجين من الأجنحة الضخمة، وقال إنه ينبغي أن يكون الشخص الذي يقيم في گواناكوري كمعبود من أجل التحدث مع أبيه الشمس. بعدها ذهبوا إلى أعلى التل. أصبح أيار أوتشى الآن في الموقع الذي سيظل فيه كمعبود، وقام برحلة نحو السماء العالية حتى أنهم لم يتمكنوا من رؤيته. عاد أيار وأخبر أيار مانكو أنه من الآن فصاعداً سيصبح اسمه مانكو كاپاك. جاء أيار أوتشى من حيث كانت الشمس، وأن الشمس قد أمرت أيار مانكو بحمل هذا الاسم والذهاب إلى المدينة التي رأوها. بعد أن صرح المعبود بهذا، تحول أيار أوتشى، بأجنحته، إلى حجر، كما كان تماماً... كان يحب المكان الذي تشغله مدينة كوسكو الحالية. صنع مانكو كاپاك ورفيقه، بمساعدة النساء الأربعة، منزلاً. بعد القيام بذلك، قام مانكو كاپاك ورفيقه، مع النساء الأربعة، بزرع الذرة في بعض الأراضي. ويقال أنهم أخذوا بذور الذرة من الكهف، الذي أطلق عليه الرب مانكو كاپاك اسم پاكاريتامبو، ويعني القادمون من الأصل.. أي الذين خرجوا من الكهف.[4]

التاريخ

ثقافة كيلكى

استوطن شعب الكيلكى Killke المنطقة من عام 900 حتى 1200، قبل وصول الإنكا في القرن 13. تأريخ كربون-14 لساكسايوامان، المجمع المسور خارج كوسكو، يشير إلى أن الكيلكى قد أنشأوا حصناً حوالي عام 1100. The Inca later expanded and occupied the complex in the 13th century. In March 2008, archeologists discovered the ruins of an ancient temple, roadway and aqueduct system at Saksaywaman.[5] The temple covers some 2,700 square feet (250 square meters) and contains 11 rooms thought to have held idols and mummies,[5] establishing its religious purpose. Together with the results of excavations in 2007, when another temple was found at the edge of the fortress, this indicates a longtime religious as well as military use of the facility.[6]

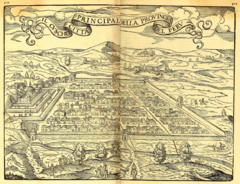

تاريخ الإنكا

Cusco was long an important center of indigenous people. It was the capital of the Inca Empire (13th century – 1532). Many believe that the city was planned as an effigy in the shape of a puma, a sacred animal.[7] How Cusco was specifically built, or how its large stones were quarried and transported to the site remain undetermined. Under the Inca, the city had two sectors: the hurin and hanan. Each was divided to encompass two of the four provinces, Chinchasuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Kuntisuyu (SW) and Qullasuyu (SE). A road led from each quarter to the corresponding quarter of the empire.

Each local leader was required to build a house in the city and live part of the year in Cusco, restricted to the quarter that corresponded to the quarter in which he held territory. After the rule of Pachacuti, when an Inca died, his title went to one son and his property was given to a corporation controlled by his other relatives (split inheritance). Each title holder had to build a new house and add new lands to the empire in order to own land for his family to keep after his death.

According to Inca legend, the city was rebuilt by Sapa Inca Pachacuti, the man who transformed the Kingdom of Cuzco from a sleepy city-state into the vast empire of Tawantinsuyu.[8] Archeological evidence, however, points to a slower, more organic growth of the city beginning before Pachacuti. The city was constructed according to a definite plan in which two rivers were channeled around the city. Archeologists have suggested that this city plan was replicated at other sites.

The city fell to the sphere of Huáscar during the Inca Civil War after the death of Huayna Capac in 1528. It was captured by the generals of Atahualpa in April 1532 in the Battle of Quipaipan. Nineteen months later, Spanish explorers invaded the city after kidnapping and murdering Atahualpa (see Battle of Cuzco), and gained control.

بعد الغزو الإسپاني

وصل أول ثلاثة إسپان المدينة في مايو 1533، بعد معركة كاجاماركا، تم تجميعهم من أجل غرفة فداء أتاوالپا. في 15 نوفمبر 1533 وصل فرانشسكو پيزارو كوسكو رسمياً. "عاصمة الإنكا... أذهلت الإسپان بجمال صروحها وطول شوارعها وانتظامها: "كانت الساحة الكبرى محاطة بعدة قصور، حيث "بنى كل ملك قصراً جديداً لنفسه". "تفوقت براعة الأعمال الحجرية في المدينة" عن نظيرتها لدى الإسپان. كان للقلعة ثلاث دريئات وتتألف من "كتل صخمة من الصخور". "عبر قلب العاصمة يجري نهرً ... في مواجهة الحجر". "إن الصرح الأكثر فخامة في كوسكو ... كان بلا شك المعبد العظيم المكرس للشمس ... المرصع باللوحات الذهبية ... والمحاط بالأديرة ومساكن الكهنة". "كانت القصور عديدة ولم تضيع القوات أي وقت في نهب محتوياتها، فضلاً عن إسقاط الصروح الدينية"، بما في ذلك المومياوات الملكية في كوريكانتشا.[9]

منح پيزارو مانكو إنكا حاشية الإنكا باعتباره القائد الپيروڤي الجديد.[9] شجع پيزارو بعض رجاله على البقاء والاستيطان في المدينة، giving out الرپارتيميينتو لفعل ذلك.[10] في 24 مارس 1534 تأسس منصب القضاة والمستشارين، وكانوا يتضمنون الأخوين گونازلو پيزارو وخوان گونازلو. ترك پيزارو حامية قوامها 90 رجل ثم غادر إلى خواخا برفقة مانكو إنكا.[9]

أعاد پيزارو تسميتها "بمدينة كوسكو شديدة النبل والعظمة". تميزت المباني المبنية بعد الغزو الإسپاني بمزيج من التأثير الإسپاني مع الهندسة المعمارية الأصلية للإنكا، بما في ذلك أحياء سانتا كلارا وسان بلاس. دمر الأسپان العديد من مباني ومعابد وقصور الإنكا. واستخدموا الأسوار الباقية كأساسات لبناء المدينة الجديدة.

أصبح الأب ڤينسنتى دى ڤالڤردى أسقفاً لكوسكو وبنى كاتدرائيته قبالة القصر. بنى دير القديس دومينيك على أطلاق بيت الشمس ودير للراهبات حيث كان بيت عذارى الشمس قائماً.[9]

أُخذت المدينة من أيدي الإسپان أثناء حصار كوسكو 1536 على يد مانكو إنكا يوپانكي، قائد [[ساپا إنكا]. على الرغم من استمرار الحصار لعشرة أشهر، إلا أنه فشل في النهاية. تمكنت قوات مانكو من استعادة المدينة في غضون بضعة أيام. وتراجع مانكو في النهاية إلى ڤيلكامابا، عاصمة دولة الإنكا الجديدة حديثة التأسيس، التي استمرت 36 عاماً أخرى لكنه لم يتمكن أبداً من العودة إلى كوسكو. خلال الصراع وعلى مدار سنوات الإستعمار الإسپاني للأمريكتين، توفي الكثير من الإنكا جراء الإصابة بالجدري.

تقع كوسكو على مجموعة من الحضارات المتراكبة، حيث بُنيت التاوانتينسويو (امبراطورية الإنكا القديمة) على هياكل الكيلكى واستبدل الإسپان المعابد الأصلية بالكنائس الكاثوليكية والقصور والمساكن للغزاة.

كانت كوسكو مركزاً للاستعمار الإسپاني وانتشار المسيحية في عالم الأنديز. أصبحت مدينة شديدة الازدهار بفضل الزراعة، تربية الماشية والتعدين، بالإضافة لتجارتها مع إسپانيا. أقام المستعمرون الإسپان الكثير من الكنائس والأديرة، بالإضافة إلى كاتدرائية، جامعة ومطرانية.

فترة الجمهورية

A major earthquake on 21 May hit in 1950, and caused damage in more than one third of the city's structures. The Dominican Priory and Church of Santo Domingo, which were built on top of the impressive Qurikancha (Temple of the Sun), were among the affected colonial era buildings. Inca architecture withstood the earthquake. Many of the old Inca walls were at first thought to have been lost after the earthquake, but the granite retaining walls of the Qurikancha were exposed, as well as those of other ancient structures throughout the city. Restoration work at the Santo Domingo complex exposed the Inca masonry formerly obscured by the superstructure without compromising the integrity of the colonial heritage.[11] Many of the buildings damaged in 1950 had been impacted by an earthquake only nine years previously.[12]

In the 1990s, during the mayoral administration of Mayor Daniel Estrada Pérez, the city underwent a new process of beautification through the restoration of monuments and the construction of plazas, fountains and monuments. Likewise, thanks to the efforts of this authority, various recognitions were achieved, such as the declaration as "Historical Capital of Peru" contained in the text of the Political Constitution of Peru of 1993. It was also decided to change the coat of arms of Cusco, leaving aside the colonial coat of arms and adopting the "Sol de Echenique" as the new coat of arms. Additionally, the change of the official name of the city was proposed to adopt the Quechua word Qosqo, but this change was reversed a few years later. Currently, Cusco is the most important tourist destination in Peru. Under the administration of mayor Daniel Estrada Pérez, a staunch supporter of the Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, between 1983 and 1995 the Quechua name Qosqo was officially adopted for the city. Tourism in the city was drastically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru and the 2022–2023 Peruvian protests, with the latter event costing the area 10 million soles daily.[13]

المناخ

| أخفClimate data for كوسكو (مطار ألخاندرو ڤلاسكو أستـِتى الدولي) 1961–1990، درجات الحرارة العظمى والصخرى 1931–الحاضر | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.8 (82.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.4 (52.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

5.1 (41.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 160.0 (6.30) |

132.9 (5.23) |

108.4 (4.27) |

44.4 (1.75) |

8.6 (0.34) |

2.4 (0.09) |

3.9 (0.15) |

8.0 (0.31) |

22.4 (0.88) |

47.3 (1.86) |

78.6 (3.09) |

120.1 (4.73) |

737.0 (29.02) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19 | 15 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 106 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 67 | 66 | 63 | 59 | 55 | 54 | 54 | 56 | 56 | 58 | 62 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143 | 121 | 170 | 210 | 239 | 228 | 257 | 236 | 195 | 198 | 195 | 158 | 2٬350 |

| Source 1: NOAA,[14] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[15] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (mean temperatures 1961–1990, precipitation days 1970–1990 and humidity 1954–1993)[16] Danish Meteorological Institute (sun 1931–1960)[17] | |||||||||||||

المعالم

بنت حضارة الكيلكى الأصلية مجموع ساكسايهوامان المحاط بالأسوار حوالي عام 1100. بنى الكيلكى معبداً رئيسياً بالقرب من الساكسايهوامان، بالإضافة إلى قناة مائية (پوكيوس) وطريقاً يصل بين مباني ما قبل التاريخ. وقام الإنكا بتوسيع الساكسايهوامان.

نهب المستكشف الإسپاني پيزارو معظم مدينة الإنكا عام 1535. لا تزال أطلال قصر الإنكا، الكوريكانتشا (معبد الشمس) ومعبد عذارى الشمس قائمة. أثبتت مباني الإنكا وأساساتها في بعض الحالات أنها أقوى من الأساسات التي بنيت في پيرو الحالية. من بين المباني الاستعمارية الإسپانية الأكثر شهرة في المدينة كاتدرائية سانتو دومينگو.

المواقع الرئيسية القريبة من الإنكا هي البيت الشتوي المفترض لپاتشاكوتي، ماتشو پيتشو، الذي يمكن الوصول إليه سيراً على الأقدام عبر ممشى الإنكا أو عن طريق القطار؛ والحصن الموجود في أولانتايتامو.

قصر أسلحة كوسكو

السكان

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 300000[18][19][بحاجة لمصدر أفضل] | — |

| 1614 | 5٬000 | — |

| 1761 | 6٬600 | +32.0% |

| 1812 | 6٬900 | +4.5% |

| 1820 | 9٬000 | +30.4% |

| 1827 | 15٬000 | +66.7% |

| 1850 | 16٬000 | +6.7% |

| 1861 | 15٬000 | −6.2% |

| 1877 | 17٬000 | +13.3% |

| 1890 | 18٬900 | +11.2% |

| 1896 | 20٬000 | +5.8% |

| 1900 | 25٬000 | +25.0% |

| 1908 | 33٬900 | +35.6% |

| 1920 | 30٬500 | −10.0% |

| 1925 | 32٬000 | +4.9% |

| 1927 | 33٬000 | +3.1% |

| 1931 | 35٬900 | +8.8% |

| 1940 | 40٬600 | +13.1% |

| 1945 | 45٬600 | +12.3% |

| 1951 | 50٬000 | +9.6% |

| 1953 | 54٬000 | +8.0% |

| 1961 | 80٬100 | +48.3% |

| 1969 | 115٬300 | +43.9% |

| 1981 | 180٬227 | +56.3% |

| 1993 | 250٬270 | +38.9% |

| 1997 | 275٬318 | +10.0% |

| 2000 | 295٬530 | +7.3% |

| 2005 | 375٬066 | +26.9% |

| 2006 | 382٬577 | +2.0% |

| 2007 | 390٬059 | +2.0% |

| 2008 | 397٬526 | +1.9% |

| 2009 | 405٬000 | +1.9% |

| 2010 | 412٬495 | +1.9% |

| 2011 | 420٬030 | +1.8% |

| 2012 | 427٬580 | +1.8% |

| 2013 | 435٬114 | +1.8% |

| 2015 | 434٬654 | −0.1% |

في 2013 كان تعداد سكان المدينة 434.114 نسمة وفي تعداد 2015 بلغ 434.654 نسمة تبعاً للمعهد الوطني للإحصاء والمعلومات.

| الحي | المساحة (كم2) |

السكان تعداد 2007 (hab) |

الإسكان (2007) |

الكثافة (hab/كم2) |

الإرتفاع (amsl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| كوسكو | 116.22 | 108.798* | 28.476 | 936.1 | 3.399 | |

| سان خرونيمو | 103.34 | 28.856* | 8.942 | 279.2 | 3.244 | |

| سان سباستيان | 89.44 | 85.472* | 18.109 | 955.6 | 3.244 | |

| سانتياگو | 69.72 | 66,277* | 21.168 | 950.6 | 3.400 | |

| واتشاك | 6.38 | 54.524* | 14.690 | 8.546.1 | 3,366 | |

| الإجمالي | 385.1 | 358.052* | 91.385 | 929.76 | — | |

| *البيانات حسب المعهد الوطني للإحصاء والمعلومات[20] | ||||||

العلاقات الدولية

المدن الشقيقة

شراكات

في الثقافة المعاصرة

- في فيلم حياة الإمبراطور الجديدة، ومسلسل الرسوم المتحركة التلفزيوني المقتبس منه مدرسة الإمبراطور الجديدة، كان الموضوع الرئيس كوزكو، إمبراطور الإنكا الخيالي، الشاب الغير ناضج.

- كان "كوزكو" اسم أغنية ضمن ألبوم إ.س. پوثموس في العام 2001 باسم Unearthed. كانت كل أغنية في الألبوم على اسم مدينة قديمة.

- رواية نجم الشيطان تأليف أنطوني هورويتز، يدور جزء من أحداثها في كوسكو.

- توفي جون پيل، دي جي راديو بي بي سي 1 في كوسكو أثناء قضاؤه عطلة عمل عام 2004.

معرض الصور

انظر أيضاً

- مدرسة كوسكو

- محافظة قشتالة الجديدة

- دين الإنكا في كوسكو

- نظام طرق الإنكا

- إپرو، معلومات ومساعدة سياحية

- قائمة المواقع الأثرية الفلكية مرتبة حسب البلد

- پيروريل

- پيكيلاكتا

- سانتورانتيكوي

- تامپوكانتشا، موقع ديني للإنكا

- السياحة في پيرو

- واناكاوري

- عجائب الدنيا السبع الحديثة

المصادر

- ^ "Perú: Población estimada al 30 de junio y tasa de crecimiento de las ciudades capitales, por departamento, 2011 y 2015". Perú: Estimaciónes y proyecciones de población total por sexo de las principales ciudades, 2012–2015 (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática). March 2012. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/web/biblioineipub/bancopub/Est/Lib1020/cuadros/c0206.xls. Retrieved on 2015-06-03. - ^ "Constitución del Perъ de 1993". Pdba.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2007). "Cuzco: La piedra donde se posó la lechuza. Historia de un nombre". Andina. Lima. 44: 143–174. ISSN 0259-9600.

- ^ Betanzos, J., 1996, Narrative of the Incas, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0292755598

- ^ أ ب Hearn, Kelly (31 March 2008). "Ancient Temple Discovered Among Inca Ruins". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on Dec 6, 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "News". Comcast.net<!. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "The history of Cusco". cusco.net<!. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ de Gamboa, P. S., 2015, History of the Incas, Lexington, ISBN 9781463688653

- ^ أ ب ت ث Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- ^ Pizzaro, P., 1571, Relation of the Discovery and Conquest of the Kingdoms of Peru, Vol. 1–2, New York: Cortes Society, RareBooksClub.com, ISBN 9781235937859

- ^ "Koricancha Temple and Santo Domingo Convent – Cusco, Peru". Sacred-destinations.com. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Erickson; et al. "The Cusco, Peru, Earthquake of May 21, 1950". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. Bssa.geoscienceworld.org. p. 97. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Vega, Ysela (6 February 2023). "Cusco sin 4.000 reservas hoteleras y pérdidas de S/10 millones al día". La Republica (in الإسبانية). Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ "Cusco Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^

"Station Alejandro Velasco" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^

"Klimatafel von Cuzco, Prov. Cuzco / Peru" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Peru – Cuzco" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Political Division, Population, Language, Religion, Orography – Cusco – Peru – Cuzco". Cusco-peru.org. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Cusco Culture – ISA". Studiesabroad.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ Censo 2005 INEI Archived 23 أبريل 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ciudades Hermanas (Sister Cities)" (in Spanish). Municipalidad del Cusco. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "::Bethlehem Municipality::". bethlehem-city.org. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kraków – Miasta Partnerskie" [Kraków -Partnership Cities]. Miejska Platforma Internetowa Magiczny Kraków (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 يوليو 2013. Retrieved 10 أغسطس 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

وصلات خارجية

وسائط متعلقة بـCusco من مشاع المعرفة.

وسائط متعلقة بـCusco من مشاع المعرفة.

![]() Cusco travel guide from Wikivoyage

Cusco travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Articles containing Quechua-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from August 2018

- Pages with empty portal template

- مواقع أثرية في پيرو

- عواصم مناطق پيرو

- كوسكو

- أماكن مأهولة في منطقة كوسكو

- مواقع التراث العالمي في پيرو

- مدن پيرو

- عواصم دول سابقة

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في القرن العاشر

- تأسيسات القرن 11 في پيرو

- تأسيسات القرن 13 في حضارة الإنكا

- انحلالات القرن 16 في حضارة الإنكا

- تأسيسات 1533 في الامبراطورية الإسپانية

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في 1533