كاوس (نشأة الكون)

| Chaos | |

|---|---|

| |

| معلومات شخصية | |

| الأنجال | گايا, ترتاروس, إربوس, نيكس وإروس[1] |

كاوس (χάος khaos) باليونانية، أي Abyss أو الهاوية، الإله الأقدم أو مصدر الكون في الميثولوجيا الإغريقية.

أصل الاسم

Greek kháos (χάος) means 'emptiness, vast void, chasm, abyss',[2] related to the verbs kháskō (χάσκω) and khaínō (χαίνω), 'gape, be wide open', from Proto-Indo-European *ǵʰeh₂n-,[3] cognate to Old English geanian, 'to gape', whence English yawn.[4]

It may also mean space, the expanse of air, the nether abyss or infinite darkness.[5] Pherecydes of Syros (fl. 6th century BC) interprets chaos as water, like something formless that can be differentiated.[6]

مفهوم كاوس

| سلسلة الآلهة اليونانية |

|---|

| الآلهة الأزلية |

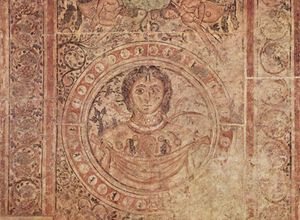

يُعتبر خاوس في علم الكونيات الإغريقي والأساطير الإغريقية الأقدم للخلق، الفراغ الأولي أو الهاوية المظلمة التي وُجد منها كل شيء (ويُجسد كالإله الأقدم)، وفي مفهوم آخر هو جحيم العالم السفلي أي ترتاروس، إلا أن هذا المفهوم غير شائع لأنه غير متلائم مع باقي الأساطير. وفي مرحلة لاحقة من علم الكونيات يشير كِياوس بشكل عام إلى الحالة الأصلية للأشياء كيفما تخيلناها. أما المعنى الحديث له فهو مشتق من كتابات أوڤيد، الذي اعتبره المادة الأولية التي لا شكل لها، والتي خُلق منها النظام الكوني. وقد تم استخدام هذا المفهوم في تفسير قصة الخلق الموجودة في الكتاب الأول من العهد القديم المسمى سفر التكوين.

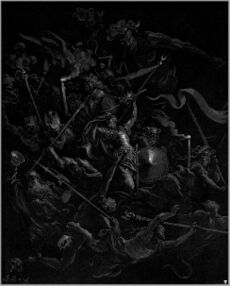

معركة كاوس

The motif of Chaoskampf (ألمانية: [ˈkaːɔsˌkampf]; حرفياً 'struggle against chaos') is ubiquitous in myth and legend, depicting a battle of a culture hero deity with a chaos monster, often in the shape of a serpent or dragon. Parallel concepts appear in the Middle East and North Africa, such as the abstract conflict of ideas in the Egyptian duality of Maat and Isfet or the battle of Horus and Set.[7]

ذريته في الميثولوجيا الإغريقية

تقول الأساطير الإغريقية أن كاوس ولّد (أنتج) الأرض والتي ارتفعت منها السماء المرصعة بالنجوم والملبدة بالغيوم. وتُجسَّد الأم الأرض بالإلهة جايا، والسماء الأب بالإله أورانوس ابن جايا وزوجها. ومن ذرية كِياوس أيضاً إيروس إله الحب، والذي يُعتبر في الاعتقادات اللاحقة ابن أفروديت. ومن ذرية كِياوس أيضاً إريبوس (أي الظلام) وزوجته نيكس إلهة الليل، والتي ولدت آيثر (الهواء العلوي المتألق) وهيميرا أي النهار. ومن ذريته أيضاً ترتاروس الذي يمثل الجحيم الأسفل من العالم السفلي.

التقليد اليوناني-الروماني

| مذاهب أساسية | |

| تعدد الآلهة · الأساطير · Hubris Orthopraxy · Reciprocity · الفضيلة | |

| الطقوس | |

|

أمفيدروميا · ياترومانتس | |

| آلهة | |

| الاولمپيون الاثنى عشر: آرس · أرتميس · أفروديت · أبولو أثينا · دميتر · هيرا · هستيا هرمس · هفستس · پوسايدون · زيوس --- الآلهة الأزلية: Aether · كاوس · خرونوس · إربوس گايا · همرا · نيكس · ترتاروس · أورانوس --- الآلهة الأصغر: ديونيسس · إروس · هبه · Hecate · هليوس هراقليس · إيريس · سلنه · پان · Nike | |

| نصوص | |

| Argonautica · إلياذة · اوديسة Theogony · الأعمال والأيام | |

| انظر أيضا: | |

| انزواء الشرك الهليني Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism Supreme Council of Ethnikoi Hellenes |

| سلسلة الآلهة اليونانية |

|---|

| الآلهة الأزلية |

Hesiod and the Pre-Socratics use the Greek term in the context of cosmogony. Hesiod's Chaos has been interpreted as either "the gaping void above the Earth created when Earth and Sky are separated from their primordial unity" or "the gaping space below the Earth on which Earth rests."[8] Passages in Hesiod's Theogony suggest that Chaos was located below Earth but above Tartarus.[9][10] Primal Chaos was sometimes said to be the true foundation of reality, particularly by philosophers such as Heraclitus.

الفترة العتيقة

In Hesiod's Theogony, Chaos was the first thing to exist: "at first Chaos came to be" (or was),[11] but next (possibly out of Chaos) came Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros (elsewhere the name Eros is used for a son of Aphrodite).[أ] Unambiguously "born" from Chaos were Erebus and Nyx.[12][13] For Hesiod, Chaos, like Tartarus, though personified enough to have borne children, was also a place, far away, underground and "gloomy," beyond which lived the Titans.[14] And, like the earth, the ocean, and the upper air, it was also capable of being affected by Zeus's thunderbolts.[15]

The notion of the temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious conception of immortality.[16] The main object of the first efforts to explain the world remained the description of its growth, from a beginning. They believed that the world arose out from a primal unity, and that this substance was the permanent base of all its being. Anaximander claims that the origin is apeiron (the unlimited), a divine and perpetual substance less definite than the common elements (water, air, fire, and earth) as they were understood to the early Greek philosophers. Everything is generated from apeiron, and must return there according to necessity.[17] A conception of the nature of the world was that the earth below its surface stretches down indefinitely and has its roots on or above Tartarus, the lower part of the underworld.[18] In a phrase of Xenophanes, "The upper limit of the earth borders on air, near our feet. The lower limit reaches down to the "apeiron" (i.e. the unlimited)."[18] The sources and limits of the earth, the sea, the sky, Tartarus, and all things are located in a great windy-gap, which seems to be infinite, and is a later specification of "chaos".[18][19]

اليونان الكلاسيكية

In Aristophanes's comedy Birds, first there was Chaos, Night, Erebus, and Tartarus, from Night came Eros, and from Eros and Chaos came the race of birds.[20]

At the beginning there was only Chaos, Night, dark Erebus, and deep Tartarus. Earth, the air and heaven had no existence. Firstly, blackwinged Night laid a germless egg in the bosom of the infinite deeps of Erebus, and from this, after the revolution of long ages, sprang the graceful Eros with his glittering golden wings, swift as the whirlwinds of the tempest. He mated in deep Tartarus with dark Chaos, winged like himself, and thus hatched forth our race, which was the first to see the light. That of the Immortals did not exist until Eros had brought together all the ingredients of the world, and from their marriage Heaven, Ocean, Earth, and the imperishable race of blessed gods sprang into being. Thus our origin is very much older than that of the dwellers in Olympus. We [birds] are the offspring of Eros; there are a thousand proofs to show it. We have wings and we lend assistance to lovers. How many handsome youths, who had sworn to remain insensible, have opened their thighs because of our power and have yielded themselves to their lovers when almost at the end of their youth, being led away by the gift of a quail, a waterfowl, a goose, or a cock.

In Plato’s Timaeus, the main work of Platonic cosmology, the concept of chaos finds its equivalent in the Greek expression chôra, which is interpreted, for instance, as shapeless space (chôra) in which material traces (ichnê) of the elements are in disordered motion (Timaeus 53a–b). However, the Platonic chôra is not a variation of the atomistic interpretation of the origin of the world, as is made clear by Plato's statement that the most appropriate definition of the chôra is "a receptacle of all becoming – its wetnurse, as it were" (Timaeus 49a), notabene a receptacle for the creative act of the demiurge, the world-maker.[21]

Aristotle, in the context of his investigation of the concept of space in physics, "problematizes the interpretation of Hesiod’s chaos as 'void' or 'place without anything in it'.[22] Aristotle understands chaos as something that exists independently of bodies and without which no perceptible bodies can exist. 'Chaos' is thus brought within the framework of an explicitly physical investigation. It has now outgrown the mythological understanding to a great extent and, in Aristotle’s work, serves above all to challenge the atomists who assert the existence of empty space."[21]

التقليد الروماني

For Ovid, (43 BC – 17/18 AD), in his Metamorphoses, Chaos was an unformed mass, where all the elements were jumbled up together in a "shapeless heap".[23]

- Ante mare et terras et quod tegit omnia caelum

- unus erat toto naturae vultus in orbe,

- quem dixere chaos: rudis indigestaque moles

- nec quicquam nisi pondus iners congestaque eodem

- non bene iunctarum discordia semina rerum.

- Before the ocean and the earth appeared— before the skies had overspread them all—

- the face of Nature in a vast expanse was naught but Chaos uniformly waste.

- It was a rude and undeveloped mass, that nothing made except a ponderous weight;

- and all discordant elements confused, were there congested in a shapeless heap. [24]

According to Hyginus: "From Mist (Caligo) came Chaos. From Chaos and Mist, came Night (Nox), Day (Dies), Darkness (Erebus), and Ether (Aether)."[25][ب] An Orphic tradition apparently had Chaos as the son of Chronus and Ananke.[27]

في التقليد التوراتي

Chaos has been linked with the term abyss / tohu wa-bohu of Genesis 1:2. The term may refer to a state of non-being prior to creation[28][29] or to a formless state. In the Book of Genesis, the spirit of God is moving upon the face of the waters, displacing the earlier state of the universe that is likened to a "watery chaos" upon which there is choshek (which translated from the Hebrew is darkness/confusion).[16][30]

The Septuagint makes no use of χάος in the context of creation, instead using the term for גיא, "cleft, gorge, chasm", in Micah 1:6 and Zacharia 14:4.[31] The Vulgate, however, renders the χάσμα μέγα or "great gulf" between heaven and hell in Luke 16:26 as chaos magnum.

This model of a primordial state of matter has been opposed by the Church Fathers from the 2nd century, who posited a creation ex nihilo by an omnipotent God.[32]

In modern biblical studies, the term chaos is commonly used in the context of the Torah and their cognate narratives in Ancient Near Eastern mythology more generally. Parallels between the Hebrew Genesis and the Babylonian Enuma Elish were established by Hermann Gunkel in 1910.[33] Besides Genesis, other books of the Old Testament, especially a number of Psalms, some passages in Isaiah and Jeremiah and the Book of Job are relevant.[34][35][36]

انظر أيضاً

انظر أيضاً

- Personal Brahman, Supreme Personality of Godhead

- Greek primordial gods

- Ginnungagap

- Tohu wa bohu

- Hundun

- creatio ex nihilo

الهامش

- ^ There are two إروس in greek mythology. One is "Desire". The first thing out of Chaos. The other is the son of أفروديت و آرس وشقيق ديموس و فوبوس و مفهوم پسيخه ووالد هدونه.

- ^ West, p. 192 line 116 Χάος, "best translated Chasm"; English chasm is a loan from Greek χάσμα, which is root-cognate with χάος. Most, p. 13, translates Χάος as "Chasm", and notes: (n. 7): "Usually translated as 'Chaos'; but that suggests to us, misleadingly, a jumble of disordered matter, whereas Hesiod's term indicates instead a gap or opening".

- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, pp. 1614 and 1616–7.

- ^ "chaos". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Lidell-Scott, A Greek–English Lexiconchaos

- ^ Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003, p. 57

- ^ Wyatt, Nicolas (2001-12-01). Space and Time in the Religious Life of the Near East (in الإنجليزية). A&C Black. pp. 210–211. ISBN 9780567049421.

- ^

Moorton, Richard F., Jr. (2001). "Hesiod as Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: A Voeglinian View". Louisiana State University. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gantz (1996, p. 3)

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony. 813-814, 700, 740 – via Perseus, Tufts University.

- ^ Gantz (1996, p. 3) says "the Greek will allow both".

- ^ أ ب ت Gantz (1996, pp. 4–5)

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony. 123 – via Persius, Tufts University.

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony. 814 – via Persius, Tufts University.

And beyond, away from all the gods, live the Titans, beyond gloomy Chaos

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony. 740 – via Perseus, Tufts University.

- ^ أ ب Guthrie, W.K.C. (2000). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans. Cambridge University Press. pp. 59, 60, 83. ISBN 9780521294201. Archived from the original on 2014-01-03.

- ^ Nilsson, Vol.I, p.743[استشهاد ناقص]; Guthrie (1952, p. 87)

- ^ أ ب ت Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003, pp. 9, 10, 20

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony. 740-765 – via Perseus, Tufts University.

- ^ Aristophanes 1938, 693–699; Morford, pp 57–58. Caldwell, p. 2, describes this avian-declared theogony as "comedic parody".

- ^ أ ب Lobenhofer, Stefan (2020). "Chaos". In Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.). Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie [Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature] (in الإنجليزية). University of Heidelberg. doi:10.11588/oepn.2019.0.68092.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Aristotle. Physics. IV 1 208b27–209a2 [...]

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses. 1.5 ff. – via Perseus, Tufts University.

- ^ Ovid & More 1922, 1.5ff.

- ^ Gaius Julius Hyginus. Fabulae. Translated by Smith; Trzaskoma. Preface.

- ^ أ ب Bremmer (2008, p. 5)

- ^ Ogden 2013, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tsumura, D., Creation and Destruction. A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament, Winona Lake/IN, 1989, 2nd ed. 2005, ISBN 978-1-57506-106-1.

- ^ C. Westermann, Genesis, Kapitel 1-11, (BKAT I/1), Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1974, 3rd ed. 1983.

- ^ Genesis 1:2, English translation (New International Version)(2011): BibleGateway.com Biblica incorporation

- ^ "Lexicon :: Strong's H1516 - gay'". www.blueletterbible.org.

- ^ Gerhard May, Schöpfung aus dem Nichts. Die Entstehung der Lehre von der creatio ex nihilo, AKG 48, Berlin / New York, 1978, 151f.

- ^ H. Gunkel, Genesis, HKAT I.1, Göttingen, 1910.

- ^ Michaela Bauks, Chaos / Chaoskampf, WiBiLex – Das Bibellexikon (2006).

- ^ Michaela Bauks, Die Welt am Anfang. Zum Verhältnis von Vorwelt und Weltentstehung in Gen. 1 und in der altorientalischen Literatur (WMANT 74), Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1997.

- ^ Michaela Bauks, ''Chaos' als Metapher für die Gefährdung der Weltordnung', in: B. Janowski / B. Ego, Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (FAT 32), Tübingen, 2001, 431-464.

وصلات خارجية

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Articles with incomplete citations from April 2019

- All articles with incomplete citations

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using infobox deity without type param

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- أساطير الشرق الأدنى القديم

- أساطير الخلق

- كاوس

- آلهة يونانية

- خيمياء

- الفلسفة اليونانية الكلاسيكية