قلعة الصبيبة

| قلعة الصبيبة | |

|---|---|

Nimrod Fortress מבצר נמרוד | |

| مرتفعات الجولان | |

| |

| الإحداثيات | 33°15′10″N 35°42′53″E / 33.252778°N 35.714722°E |

| النوع | قلعة |

| معلومات الموقع | |

| مفتوح للعامة | April–September: 8 a.m. – 5 p.m. October–March: 8 a.m. – 4 p.m. |

| تاريخ الموقع | |

| بُني | البنية المبكرة : الفترة الهلنستية (حتى 30 م) / الفترة البيزنطية (القرن الرابع إلى السابع الميلادي) البنية المتأخرة : الفترة الأيوبية (القرن الثاني عشر والثالث عشر) Between 1229 and 1290[1] |

| بناه | البنية المبكرة : غير معروفة البنية المتأخرة :العزيز عثمان |

قلعة النمرود أو قلعة الصبيبة، أو قلعة الجرف الكبير، هي قلعة بناها الأيوبيون وقام المماليك بتوسيعها بشكل كبير، تقع على المنحدرات الجنوبية لـ جبل الشيخ، على سلسلة من التلال ترتفع حوالي 800 م (2600 قدم) فوق مستوى سطح البحر. تطل على مرتفعات الجولان وقد تم بناؤها بغرض حراسة طريق الوصول الرئيسي إلى دمشق ضد الجيوش القادمة من الغرب.

Alternative forms and spellings include: Kal'at instead of Qal'at, the prefix as- instead of al-, and Subayba, Subaybah and Subeibeh in place of Subeiba.

إن ارتباط القلعة بالملك التوراتي، المحارب الجبار والصياد نمرود، الذي دخل الأدب التفسيري الإسلامي في فترة ما بعد القرآن باسم نمرود، جاء من الدروز، الذين استقروا في المنطقة فقط في القرن التاسع عشر.[2]

وتقع المنطقة تحت الاحتلال والإدارة الإسرائيلية منذ عام 1967 إلى جانب مرتفعات الجولان المجاورة. ويرى المجتمع الدولي المنطقة على أنها أرض سورية.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

الفترة القديمة (الهلينية؟)

استنادا إلى الاكتشافات الأثرية (ما يسمى "نمط البناء الضخم" وغيرها من العناصر الهلنستية النموذجية، تليها أساليب البناء الصليبية والأيوبية والمملوكية) ودراسة تأثير الأحداث الزلزالية على البناء، المرتبطة بالمعرفة التاريخية حول أهم بسبب الزلازل الإقليمية، توصل الباحثون إلى استنتاج مفاده أنه من المحتمل أن تكون القلعة الأولى قد بنيت في الموقع من قبل اليونانيين السوريين القدماء، أي خلال الفترة الهلنستية (بعد 332 قبل الميلاد)، ولكن ليس من قبل الهيروديانيين أو الرومان (الذين حكموا المنطقة من القرن الأول قبل الميلاد فصاعدًا).[3]

تم ذكر الفينيقيين أيضًا كاحتمال من قبل إدوارد روبنسون في عام 1856.[3] تم تحديد الزلزال الذي دمر أقدم المباني على أنه حدث الكارثي 749.

من هم بناة القلعة الأولى على وجه التحديد، لا يزال يتعين إجراء تحقيقات أثرية فيها.[3]

العصر الصليبي

استنادًا إلى أسلوب البناء والبناء، بما في ذلك أولاً وقبل كل شيء الأقبية المضلعة ذات الأشكال المتقاطعة للقاعة الشرقية في القسم الداخلي للقلعة (وهو شكل لم يستخدمه المسلمون مطلقًا)، يعتبر ألون مارجاليت أن مرحلة البناء الصليبية أثبتت جدواها.[3] يُظهر البناء الصليبي علامات من نوع مختلف من الضرر الزلزالي، يعود تاريخه إلى زلزال 1202 ويغيب عن البناء الأيوبي والمملوكي اللاحق.[3]

الأيوبيون والمغول

أعيد بناء القلعة حوالي عام 1228[3] على يد العزيز عثمان ابن العادل شقيق صلاح الدين الأيوبي، استباقاً لهجوم على دمشق من قبل جيوش الحملة الصليبية السادسة.[4][5]

سميت قلعة الصبيبة، "قلعة الجرف الكبير". تم توسيع القلعة لتشمل التلال بأكملها بحلول عام 1230. وفي عام 1260 استولى المغول على القلعة وفككوا بعض دفاعاتها وتركوا حليفهم ابن العزيز عثمان مسؤولاً عنها و بلدة بانياس القريبة.[6]

العصر المملوكي

بعد انتصار المماليك على المغول في معركة عين جالوت، قام السلطان بيبرس بتعزيز القلعة وإضافة أبراج أكبر. أُعطيت القلعة للرجل الثاني في قيادة بيبرس، بيليك. بدأ المحافظ الجديد أنشطة البناء واسعة النطاق. عندما تم الانتهاء من البناء، أحيا بيليك ذكرى عمله ومجد اسم السلطان في نقش عام 1275. بعد وفاة بيبرس، رتب ابنه لقتل بيليك، على ما يبدو لأنه كان يخشى سلطته.

في نهاية القرن الثالث عشر، بعد الفتح الإسلامي لمدينة عكا الساحلية ونهاية الحكم الصليبي في الأرض المقدسة، فقدت القلعة قيمتها الاستراتيجية وسقطت في حالة سيئة.

العصر العثماني

استولى الأتراك العثمانيون على الأرض عام 1517 واستخدموا القلعة كسجن فاخر للنبلاء العثمانيين. تم التخلي عن القلعة في وقت لاحق من القرن السادس عشر وكان الرعاة المحليون وقطعانهم هم الضيوف الوحيدون داخل أسوارها.

تعرضت القلعة لأضرار جسيمة بسبب زلزال عام 1759 الذي ضرب المنطقة.[7]

الدروز الذين أتوا إلى المنطقة أثناء صراع 1860 بينهم وبين الموارنة بدأوا يطلقون عليها اسم قلعة النمرود.[8]

الوصف

تشغل القلعة جرفاً صخرياً متطاولاً فوق هضبة عالية في لحف الجبل تزداد ارتفاعاً باتجاه الشمال وتواجه دفاعاتها الرئيسية الجبال من الشمال. طولها من الشرق إلى الغرب نحو 435م ويراوح عرضها من الشمال إلى الجنوب بين 75 و165م. تتألف القلعة من معقل رئيس مرتفع في الجهة الشرقية يسمى «القِلَّة» أو «القليعة» وهي على هيئة برج محصن محاط بفناء صغير مسوَّر، ومن قلعة سفلية تضم بقية أجزائها ويحيط بها جميعاً سور ساتر. وقد تطلبت الانحدارات المتواضعة لسفوح الجبل من جهة الجنوب إقامة أقوى التحصينات في القلعة، فشُيدت على هذا الجناح ستة أبراج مستطيلة مدمجة في السور تبرز عنه قليلاً وشيد برجان دائريان حصينان للدفاع الجانبي، أما الجناح الشمالي فيتمتع بحماية طبيعية على ريف صخري شديد الانحدار لا يحميه سوى سور قليل الارتفاع غير منتظم يتماشى مع حافة الهضبة، وأما الجهة الغربية فحصنت بسور طوله 165م مزود بأربعة أبراج مربعة ومستطيلة تبرز عن السور مسافة 7-10م.

مشيدة فوق مرتفع مثلث الشكل محصور بين نهري سعار وبانياس قبيل التقائهما. وجدران هذه القلعة متقوضة جداً لم يبق ظاهراً منها الا القليل. والقادم لزيارة اثار بانياس يبدأ من الجهة الشمالية الغربية. فيرى ثمة على ضفة النهر برجين ضخمين من العصور المتوسطة. وكان برج ثالث على بعد قليل عنهما، إلى الجنوب وغربي الطريق الحالية. وكانت جدران الأسوار مدعومة بأعمدة روابط أقحمت في هذه الجدران، كما هو الحال في كثير من القلاع. وهذه الأعمدة إما من حجر البلاد الكلسي وإما من الحجر المحبب (الغرانيت) الأسود المرقط المجلوب من صعيد مصر. وكلها من بقايا المباني التي كانت في العهد الروماني. وإذا سلك الزائر السكة القديمة يخترق القرية ويبلغ الجسر العتيق الذي كان في الزاوية الجنوبية الشرقية. وكان هذا الجسر محمياً ببوابة قوية اقحمت أيضاً في جدرانها أعمدة روابط من الغرانيت. وترى حتى الآن بعضها ملقى على جانب الطريق وثمة باب له اسكفة ذات كتابة عربية . وكانت حصون بانياس تمتد على طول ضفة النهر في الشرق والغرب. والمداميك السفلية في هذه المباني مؤلفة من أحجار ضخمة منحوتة نحتاً بارزاً (صورياً) تدل على عراقتها في القدم. أما المداميك العليا فهي من العهود الإسلامية، كما تشهد بذلك بقايا الجدران المبنية من أحجار كبيرة، وقطع الأعمدة المنحوتة.

وإذا رجع الزائر أدراجه وتقدم نحو الجبل، يصل بعد بضع دقائق إلى نبع المياةالصاخب الجميل، فيجد المياه تسيل بغزارة كلية من حضيض جدار شاهق من الصخر الكلسي. وهذا النبع هو الهدف الأسمى في زيارة بانياس. وفي الجدار الشاهق المذكور يلحظ الناظر وجود غرف عديدة، وخمس كوى منقورة في الصخر، مع كتابات يونانية صعبة القراءة، كانت فيما يظن مخصصة لوضع السمامات. وهنالك أيضاً مغارة طبيعية، قد سد مدخلها بصخور ضخمة، متدحرجة من أعلى الجبل، . وفي فصل الشتاء يمتلئ قعر المغارة بالماء، وفي فصل الصيف تجف . ويعتقد الأثريون أن هذه هي المغارة التي كانت مكرسة إلى الإله "پان" أو "بانيون" الذي أعطى المدينة اسمه. وينابيع المياه في بانياس صافية الماء رقراقه، هو يتفجر بفوران شديد، وينقسم إلى فرعين ليؤلف نهراً عرضه من 4 -6، أمتار يندفع راغياً مزبداً هادراً في مسيل صخري ( ينابيع الجولان ) التي تكون عدة أنهار هامة.

معرض

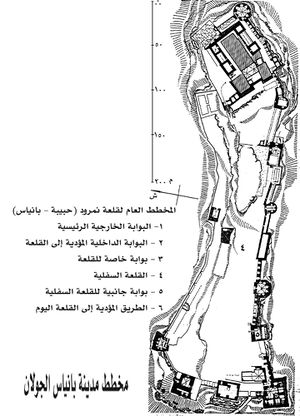

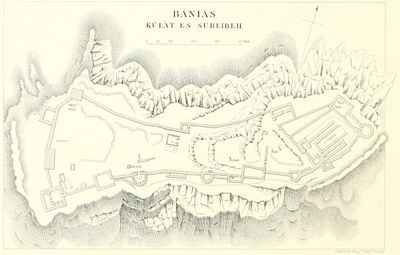

Plan from the 1871-77 PEF Survey of Palestine

المراجع

- ^ Devir, Ori, Off the Beaten Track in Israel, Adama Books (New York, 1989), p. 16 ISBN 0-915361-28-0.

- ^ Jonathan Klawans. "Site-Seeing: Nimrod: A Golan fortress fit for a giant", Bible History Daily, 14 November 2018. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society (BAS). Accessed 26 March 2024.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Margalit, Alon. "Differential earthquake footprints on the masonry styles at Qal’at al-Subayba (Nimrod fortress) support the theory of its ancient origin". In Heritage Science 6: 62, 29 October 2018, DOI:10.1186/s40494-018-0227-9?. Re-accessed 26 March 2024.

- ^ Ronnie Ellenblum (1989). "Who Built Qalʿat al-Ṣubayba?". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 43: 103–112. doi:10.2307/1291606. JSTOR 1291606.

- ^ Reuven Amitai (1989). "Notes on the Ayyūbid Inscriptions at al-Ṣubayba (Qalʿat Nimrūd)". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 43: 113–119. doi:10.2307/1291607. JSTOR 1291607.

- ^ Reuven Amitai-Preiss (2005). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780521522908. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ "Nimrod Fortress". Beinharim Tourism Services. Beinharim Tourism Servic. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Sharon, Moshe (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae: B v. 1 (Handbook of Oriental Studies) (Hardcover ed.). Brill Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 90-04-11083-6.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2000). Crusader Castles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79913-9.

وصلات خارجية

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with dead external links from October 2023

- Articles with إنگليزية-language sources (en)

- Articles with عبرية-language sources (he)

- 13th-century fortifications

- Castles in Syria

- Mamluk castles

- National parks of Israel

- Medieval sites on the Golan Heights

- Tourist attractions in the Golan Heights

- Forts in Syria

- Sixth Crusade

- قلاع الدولة الإسماعيلية النزارية

- Mount Hermon