فضاء إسقاطي

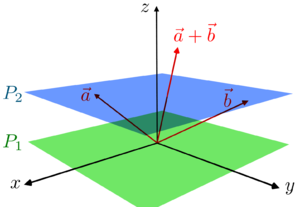

في الرياضيات، الفضاء الإسقاطي Projective space هو التركيب الأساسي، الناتج عن فضاء اتجاهي ضمن حلقة قسمة division ring معينة, بشكل خاص على حقل معرف ما.

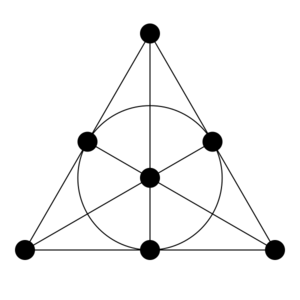

هو اذا عبارة عن تعميم لرمز المستوي الاسقاطي projective plane ، الذي يتشكل من فضاء شعاعي ثلاثي الأبعاد .

تعتبر الفضاءات الإسقاطية أساسية في الهندسة الجبرية من خلال حقل الهندسة الإسقاطية الغني الذي طور في القرن التاسع عشر ، و أيضا في تشكيل النظرية الحديثة المعتمدة على الجبر التدريجي graded algebra .

In topology, and more specifically in manifold theory, projective spaces play a fundamental role, being typical examples of non-orientable manifolds.

الدافع

مفاهيم ذات صلة

الفضاء الجزئي

Let P(V) be a projective space, where V is a vector space over a field K, and

be the canonical map that maps a nonzero vector to its equivalence class, which is the vector line containing p with the zero vector removed.

Every linear subspace W of V is a union of lines. It follows that p(W) is a projective space, which can be identified with P(W).

A projective subspace is thus a projective space that is obtained by restricting to a linear subspace the equivalence relation that defines P(V).

If p(v) and p(w) are two different points of P(V), the vectors v and w are linearly independent. It follows that:

- There is exactly one projective line that passes through two different points of P(V)

and

- A subset of P(V) is a projective subspace if and only if, given any two different points, it contains the whole projective line passing through these points.

In synthetic geometry, where projective lines are primitive objects, the first property is an axiom, and the second one is the definition of a projective subspace.

Span

التبويب

- Dimension 0 (no lines): The space is a single point.

- Dimension 1 (exactly one line): All points lie on the unique line.

- Dimension 2: There are at least 2 lines, and any two lines meet. A projective space for n = 2 is equivalent to a projective plane. These are much harder to classify, as not all of them are isomorphic with a PG(d, K). The Desarguesian planes (those that are isomorphic with a PG(2, K)) satisfy Desargues's theorem and are projective planes over division rings, but there are many non-Desarguesian planes.

- Dimension at least 3: Two non-intersecting lines exist. Veblen & Young (1965) proved the Veblen–Young theorem that every projective space of dimension n ≥ 3 is isomorphic with a PG(n, K), the n-dimensional projective space over some division ring K.

الفضاءات والمستويات الإسقاطية المحدودة

تعميمات

- dimension

- The projective space, being the "space" of all one-dimensional linear subspaces of a given vector space V is generalized to Grassmannian manifold, which is parametrizing higher-dimensional subspaces (of some fixed dimension) of V.

- sequence of subspaces

- More generally flag manifold is the space of flags, i.e., chains of linear subspaces of V.

- other subvarieties

- Even more generally, moduli spaces parametrize objects such as elliptic curves of a given kind.

- other rings

- Generalizing to associative rings (rather than only fields) yields, for example, the projective line over a ring.

- patching

- Patching projective spaces together yields projective space bundles.

Severi–Brauer varieties are algebraic varieties over a field k, which become isomorphic to projective spaces after an extension of the base field k.

Another generalization of projective spaces are weighted projective spaces; these are themselves special cases of toric varieties.[1]

انظر أيضاً

تعميمات

الهندسة الإسقاطية

مواضيع ذات صلة

الهامش

- ^ Mukai 2003, example 3.72

المراجع

- قالب:Eom

- Baer, Reinhold (2005) [first published 1952], Linear Algebra and Projective Geometry, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-44565-6

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998), Projective geometry: from foundations to applications, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48277-6

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1974), Introduction to Geometry, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-18283-4, https://archive.org/details/introductiontoge0002coxe

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1969), Projective geometry, Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-2104-2, OCLC 977732

- Dembowski, P. (1968), Finite geometries, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 44, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-61786-8, https://archive.org/details/finitegeometries0000demb

- Greenberg, M.J.; Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries, 2nd ed. Freeman (1980).

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, esp. chapters I.2, I.7, II.5, and II.7

- Hilbert, D. and Cohn-Vossen, S.; Geometry and the imagination, 2nd ed. Chelsea (1999).

- Mukai, Shigeru (2003), An Introduction to Invariants and Moduli, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-80906-1

- Veblen, Oswald; Young, John Wesley (1965), Projective geometry. Vols. 1, 2, Blaisdell Publishing Co. Ginn and Co. New York-Toronto-London (Reprint of 1910 edition)