شونخوا، ناحية السلار الذاتية

Xunhua

循化县 | |

|---|---|

| Xunhua Salar Autonomous County 循化撒拉族自治县 Gökhdengiz Velayat Yisyr Salyr Özbashdak Yurt | |

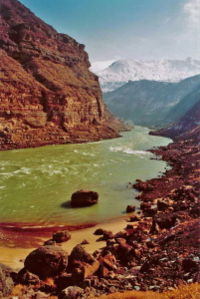

النهر الأصفر في چينگهاي، 2008 | |

Xunhua County (pink) within Haidong City (yellow) and Qinghai | |

| الإحداثيات (Xunhua government): 35°51′04″N 102°29′21″E / 35.8512°N 102.4891°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | چينگهاي |

| Prefecture-level city | Haidong |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 2٬100 كم² (810 ميل²) |

| التعداد (2000) | |

| • الإجمالي | 104٬452 |

| • الكثافة | 50/km2 (130/sq mi) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 811100 |

Xunhua Salar Autonomous County (Chinese: 循化撒拉族自治县; pinyin: Xúnhuà Sǎlázú Zìzhìxiàn; قالب:Lang-slr) is an autonomous Salar county in the southeast of Haidong Prefecture of Qinghai Province, China, and the only autonomous Salar county in China.[1] The county has an area of around 2,100 square kilometres (810 sq mi) and approximately 104,452 inhabitants (2000). In the east it borders on the province of Gansu, in the south and the west to the Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, its postal code is 811100 and its capital is the town of Jishi.

The Salar language is the official language in Xunhua, as in all Salar autonomous areas.[2]

As of April 2009, Xunhua is also the site of a mosque containing the oldest hand-written copy of the Quran in China, believed to have been written sometime between the 8th and 13th centuries.[3]

History

Xunhua County is the location of the Bronze Age necropolis Suzhi (Suzhi mudi, 苏志墓地) of the Kayue culture.

Post Salar migration and settlement

After the Oghuz Turkmen Salars moved from Samarkand in Central Asia to Xunhua, Qinghai in the early Ming dynasty, they converted Tibetan women to Islam and the Tibetan women were taken as wives by Salar men. A Salar wedding ritual where grains and milk were scattered on a horse by the bride was influenced by Tibetans.[4] After they moved into northern Tibet, the Salars originally practiced the same Gedimu (Gedem) variant of Sunni Islam as the Hui people and adopted Hui practices like using the Hui Jingtang Jiaoyu Islamic education during the Ming dynasty which derived from Yuan dynasty Arabic and Persian primers. One of the Salar primers was called "Book of Diverse Studies" (雜學本本 Zaxue Benben) in Chinese. The version of Sunni Islam practiced by Salars was greatly impacted by Salars marrying with Hui who had settled in Xunhua. The Hui introduced new Naqshbandi Sufi orders like Jahriyya and Khafiyya to the Salars and eventually these Sufi orders led to sectarian violence involving Qing soldiers (Han, Tibetans and Mongols) and the Sufis which included the Chinese Muslims (Salars and Hui). Ma Laichi brought the Khafiyya Naqshbandi order to the Salars and the Salars followed the Flowered mosque order (花寺門宦) of the Khafiyya. He preached silent dhikr and simplified Qur'an readings bringing the Arabic text Mingsha jing (明沙經, 明沙勒, 明沙爾 Minshar jing) to China.[5]

The Kargan Tibetans, who live next to the Salar, have mostly become Muslim due to the Salars. The Salar oral tradition recalls that it was around 1370 in which they came from Samarkand to China.[6]

Tibetan women were the original wives of the first Salars to arrive in the region as recorded in Salar oral history. The Tibetans agreed to let their Tibetan women marry Salar men after putting up several demands to accommodate cultural and religious differences. Hui and Salar intermarry due to cultural similarities and following the same Islamic religion. Older Salars married Tibetan women but younger Salars prefer marrying other Salars. Han and Salar mostly do not intermarry with each other unlike marriages of Tibetan women to Salar men. Salars however use Han surnames. Salar patrilineal clans are much more limited than Han patrilinial clans in how much they deal with culture, society or religion.[7][8] Salar men often marry a lot of non-Salar women and they took Tibetan women as wives after migrating to Xunhua according to historical accounts and folk histories. Salars almost exclusively took non-Salar women as wives like Tibetan women while never giving Salar women to non-Salar men in marriage except for Hui men who were allowed to marry Salar women. As a result Salars are heavily mixed with other ethnicities.[9]

Salars in Qinghai live on both banks of the Yellow river, south and north, the northern ones are called Hualong or Bayan Salars while the southern ones are called Xunhua Salars. The region north of the Yellow river is a mix of discontinuous Salar and Tibetan villages while the region south of the yellow river is solidly Salar with no gaps in between, since Hui and Salars pushed the Tibetans on the south region out earlier. Tibetan women who converted to Islam were taken as wives on both banks of the river by Salar men. The term for maternal uncle (ajiu) is used for Tibetans by Salars since the Salars have maternal Tibetan ancestry. Tibetans witness Salar life passages in Kewa, a Salar village and Tibetan butter tea is consumed by Salars there as well. Other Tibetan cultural influences like Salar houses having four corners with a white stone on them became part of Salar culture as long as they were not prohibited by Islam. Hui people started assimilating and intermarrying with Salars in Xunhua after migrating there from Hezhou in Gansu due to the Chinese Ming dynasty ruling the Xunhua Salars after 1370 and Hezhou officials governed Xunhua. Many Salars with the Ma surname appear to be of Hui descent since a lot of Salars now have the Ma surname while in the beginning the majority of Salars had the Han surname. Some example of Hezhou Hui who became Salars are the Chenjia (Chen family) and Majia (Ma family) villages in Altiuli where the Chen and Ma families are Salars who admit their Hui ancestry. Marriage ceremonies, funerals, birth rites and prayer were shared by both Salar and Hui as they intermarried and shared the same religion since more and more Hui moved into the Salar areas on both banks of the Yellow river. Many Hui married Salars and eventually it became far more popular for Hui and Salar to intermarry due to both being Muslims than to non-Muslim Han, Mongols and Tibetans. The Salar language and culture however was highly impacted in the 14th–16th centuries in their original ethnogenesis by marriage with Mongol and Tibetan non-Muslims with many loanwords and grammatical influence by Mongol and Tibetan in their language. Salars were multilingual in Salar and Mongol and then in Chinese and Tibetan as they trade extensively in the Ming, Qing and Republic of China periods on the yellow river in Ningxia and Lanzhou in Gansu.[10]

Salars and Tibetans both use the term maternal uncle (ajiu in Salar and Chinese, azhang in Tibetan) to refer to each other, referring to the fact that Salars are descendants of Tibetan women marrying Salar men. After using these terms they often repeat the historical account how Tibetan women were married by 2,000 Salar men who were the First Salars to migrate to Qinghai. These terms illustrate that Salars were viewed separately from the Hui by Tibetans. According to legend, the marriages between Tibetan women and Salar men came after a compromise between demands by a Tibetan chief and the Salar migrants. The Salar say Wimdo valley was ruled by a Tibetan and he demanded the Salars follow 4 rules in order to marry Tibetan women. He asked them to install on their houses's four corners Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags, to pray with Tibetan Buddhist prayer wheels with the Buddhist mantra om mani padma hum and to bow before statues of Buddha. The Salars refused those demands saying they did not recite mantras or bow to statues since they believed in only one creator god and were Muslims. They compromised on the flags in houses by putting stones on their houses' corners instead of Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags. Some Tibetans do not differentiate between Salar and Hui due to their Islamic religion. In 1996, Wimdo township only had one Salar because Tibetans whined about the Muslim call to prayer and a mosque built in the area in the early 1990s so they kicked out most of the Salars from the region. Salars were bilingual in Salar and Tibetan due to intermarriage with Tibetan women and trading. It is far less likely for a Tibetan to speak Salar.[11] Tibetan women in Xiahe also married Muslim men who came there as traders before the 1930s.[12]

In eastern Qinghai and Gansu there were cases of Tibetan women who stayed in their Buddhist Lamaist religion while marrying Chinese Muslim men and they would have different sons who would be Buddhist and Muslims, the Buddhist sons became Lamas while the other sons were Muslims. Hui and Tibetans married Salars.[13]

The later Qing dynasty and Republic of China Salar General Han Youwen was born to a Tibetan woman named Ziliha (孜力哈) and a Salar father named Aema (阿额玛).[14][15][16]

In 1917, the Hui Muslim General Ma Anliang ordered his younger brother Ma Guoliang to suppress a rebellion of Tibetans in Xunhua who rebelled because of taxes Ma Anliang imposed on them. Ma Anliang did not report it to the central government in Beijing and was reprimanded for it and the Hui Muslim General Ma Qi was sent by the government to investigate the case and suppress the rebellion.[17]

| أظهرجزء من سلسلة عن الإسلام في الصين |

|---|

Ethnic groups in Xunhua, 2000 census

| Nationality | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Salar | 63,859 | 61.14% |

| Tibetan | 25,783 | 24.68% |

| Hui | 8,155 | 7.81% |

| Han | 6,217 | 5.95% |

| Tu | 134 | 0.13% |

| Dongxiang | 116 | 0.11% |

| Mongol | 39 | 0.04% |

| Qiang | 35 | 0.03% |

| Bonan | 22 | 0.02% |

| Blang | 18 | 0.02% |

| Buyei | 12 | 0.01% |

| Others | 62 | 0.06% |

See also

المراجع

- ^ 青海海东民族团结故事:黄河两岸兄弟情_循化县. Sohu 搜狐 (in الصينية). 2020-06-21. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Martí, Fèlix; Ortega, Paul; Idiazabal, Itziar; Barreña, Antoni; Juaristi, Patxi; Junyent, Carme; Uranga, Belen; Amorrortu, Estibaliz (2005). Words and Worlds: World Languages Review (illustrated ed.). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. p. 123. ISBN 1-85359-827-5.

- ^ "China's Oldest Handwritten Copy of the Koran to Open to Public". Xinhua. 2009-04-09. Archived from the original on March 25, 2010.

- ^ Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 17. ISBN 978-3447040914.

- ^ Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1. Vol. 37 of Turcologica Series, Turcologica, Bd. 37 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 18. ISBN 978-3447040914.

Tibetans south of the Yellow river were displaced much earlier by Salar and ... intermarried extensively with local Tibetan women , under the condition that ...

- ^ Rockhill, W. Woodville (1894). "A Journey in Mongolia and in Tibet". The Geographical Journal. 3 (5): 362. doi:10.2307/1773519. JSTOR 1773519.

- ^ Yang, Shengmin; Wu, Xiujie (2018). "Theoretical Paradigm or Methodological Heuristic? Reflections on Kulturkreislehre with Reference to China". In Holt, Emily (ed.). Water and Power in Past Societies. SUNY Series, The Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology Distinguished Monograph Series (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1438468754.

The Salar did and do not fully exclude intermarriage with other ethnic groups. ... reached that allowed Salar men to marry Tibetan women (Ma 2011, 63).

- ^ Yang, Shengmin; Wu, Xiujie (2018). "Theoretical Paradigm or Methodological Heuristic? Reflections on Kulturkreislehre with Reference to China". In Arnason, Johann P.; Hann, Chris (eds.). Anthropology and Civilizational Analysis: Eurasian Explorations. SUNY series, Pangaea II: Global/Local Studies (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1438469393.

The Salar did and do not fully exclude intermarriage with other ethnic groups. ... reached that allowed Salar men to marry Tibetan women (Ma 2011, 63).

- ^ Han, Deyan (1999). Translated by Ma, Jianzhong; Stuart, Kevin. "The Salar "Khazui" System". Central Asiatic Journal. 43 (2): 212. JSTOR 41928197.

towards outsiders, the Salar language has been retained. Additionally, the ethnic group has been continuously absorbing a great amount of new blood from other nationalities. In history, with the exception of Hui, there is no case of a Salar's daughter marrying a non-Salar. On the contrary , many non – Salar females married into Salar households . As folk acounts and historical records recount , shortly after Salar ancestors reached Xunhua , they had relationships with neighbouring Tibetans through marriage .

- ^ Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1. Vol. 37 of Turcologica Series, Turcologica, Bd. 37 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-3447040914.

Tibetans south of the Yellow river were displaced much earlier by Salar and ... intermarried extensively with local Tibetan women , under the condition that ...

- ^ Simon, Camille (2015). "Linguistic Evidence of Salar-Tibetan Contacts in Amdo". In M Hille, Marie-Paule; Horlemann, Bianca; Nietupski, Paul K. (eds.). Muslims in Amdo Tibetan Society: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Studies in Modern Tibetan Culture. Marie-Paule Hille, Bianca Horlemann, Paul K. Nietupski, Chang Chung-Fu, Andrew M. Fischer, Max Oidtmann, Ma Wei, Alexandre Papas, Camille Simon, Benno R. Weiner, Yang Hongwei. Lexington Books. pp. 90, 91, 264, 267, 146. ISBN 978-0739175309.

... 146, 151n36; between Muslim tradesmen and local women, 149n15; oral history of the first matrimonial alliances between Salar men and Tibetan women, ...

- ^ Nietupski, Paul K. (2015). "Islam and Labrang Monastery: A Muslim Community in a Tibetan Buddhist Estate". In M Hille, Marie-Paule; Horlemann, Bianca; Nietupski, Paul K. (eds.). Muslims in Amdo Tibetan Society: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Studies in Modern Tibetan Culture. Marie-Paule Hille, Bianca Horlemann, Paul K. Nietupski, Chang Chung-Fu, Andrew M. Fischer, Max Oidtmann, Ma Wei, Alexandre Papas, Camille Simon, Benno R. Weiner, Yang Hongwei. Lexington Books. pp. 90, 91, 264, 267, 146. ISBN 978-0739175309.

- ^ Zarcone, Thierry (1995). "Sufism from Central Asia among the Tibetan in the 16–17th Centuries". The Tibet Journal. 20 (3): 101. JSTOR 43300545.

Central Asian Sufi Masters who gave to the founder of the Chinese Qādiriyya his early training.25 Gladney wrote in his book Chinese Muslims that Afāq Khvāja preached to the northeastern Tibetans but he does not tell us what are his sources. ... The cities of northwestern China visited by the khvāja are Xining (in Qinghai), Hezhou (the old name for Linxia, the Chinese Mecca) in Gansu and Xunhua near the Gansu-Qinghai border where the Salar Turks live amidst a predominantly Tibetan Buddhist population. Gansu is a natural corridor linking China with Eastern Turkestan and Central Asia It is a ... passageway through which the silk road slipped between the Tibetan plateau to the west and the Mongolian grasslands to the north. In addition to the Chinese and the Tibetans , Gansu was also home to different people like the Salar Turks and the Dongxiang or Mongol Muslims, both preached to by Afāq Khvāja. ... (actually the city of Kuna according to Nizamüddin Hüsäyin.26 Although the Salars intermarried with the Tibetans, Chinese and Hui, they have maintained their customs until now. From the Mission d'Ollone who explored this area at the beginning of the century , we learn that some Chinese Muslims of this area married Tibetan women who had kept their religion , i . e . Lamaism , and that their sons were either Muslim or Buddhist. We are told for example that in one of these families, there was one son who was a Muslim and the other who became a Lama. Between the monastery of Lha-brang and the city of Hezhou (Linxia, it is also indicated that there were Muslims living in most of the Chinese and Tibetan...

- ^ 秉默, ed. (2008-10-16). "韩有文传奇 然 也". 中国国民党革命委员会中央委员会. 民革中央. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ 朱, 国琳 (2011-03-03). "马呈祥在新疆". 民族日报-民族日报一版. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2016-03-04 suggested (help) - ^ 韩, 芝华 (2009-10-16). "怀念我的父亲──韩有文". 中国国民党革命委员会新疆维吾尔自治区委员会. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06.

- ^ Zhao, Songyao 赵颂尧 (1989). 马安良其人与民初的甘肃政争. 西北民族大学学报(哲学社会科学版) (in الصينية). 1989 (2): 19–25.

قالب:Other ethnic minorities autonomy in the People's Republic of China

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 uses الصينية-language script (zh)

- CS1 الصينية-language sources (zh)

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing Salar-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Autonomous counties of the People's Republic of China

- County-level divisions of Qinghai

- Haidong

- Salar people