أقمار زحل

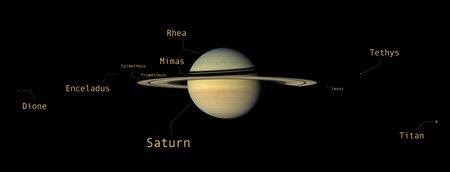

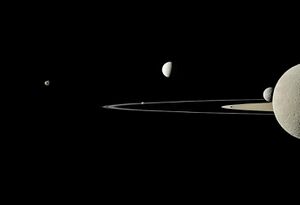

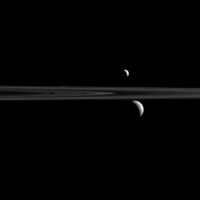

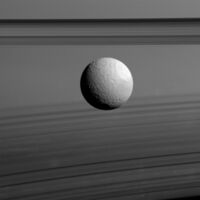

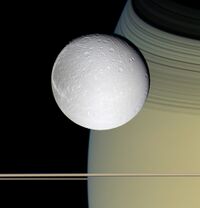

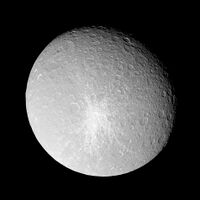

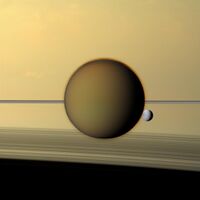

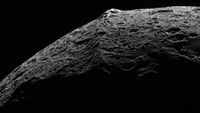

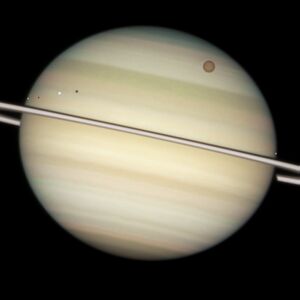

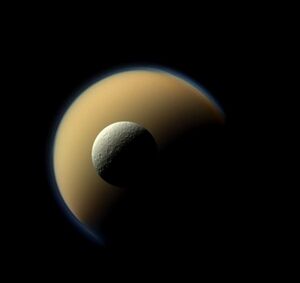

أقمار زحل عديدة ومتنوعة، بدءًا من القمر الصغير الذي يبلغ عرضه عشرات الأمتار فقط إلى القمر الضخم تيتان، وهو أكبر من كوكب عطارد.[1] اعتباراً من مايو 2013، كان لزحل 145 قمراً بمدارات مؤكدة. عام 2023، أعلن اكتشاف 62 قمراً جديداً لكوكب زحل، [2] واعتباراً من 11 مايو 2023، نُشر منها 41 مداراً فقط. هذه الأقمار الـ41 هي S/2020 S 1، S/2006 S 9، S/2007 S 5، S/2004 S 40، S/2019 S 2، S/2019 S 3، S/2020 S 2، S/2020 S 3، S/2019 S 4، S/2004 S 41، S/2020 S 4، S/2020 S 5، S/2007 S 6، S/2004 S 42، S/2006 S 10، S/2019 S 5، S/2004 S 43، S/2004 S 44، S/2004 S 45، S/2006 S 11، S/2006 S 12، S/2019 S 6، S/2006 S 13، S/2019 S 7، S/2019 S 8، S/2019 S 9، S/2004 S 46، S/2019 S 10، S/2004 S 47، S/2019 S 11، S/2006 S 14، S/2019 S 12، S/2020 S 6، S/2019 S 13، S/2005 S 4، S/2007 S 7، S/2007 S 8، S/2020 S 7، S/2019 S 14، S/2019 S 15، ةS/2005 S 5، التي نُشرت في منشورات مركز الكواكب الصغرى.[3]}} لا يشمل هذا الرقم الآلاف من الأقمار الصغيرة المضمنة في حلقات كثيفة، ولا مئات من الأقمار البعيدة التي يبلغ حجمها كيلومترًا والتي شوهدت من خلال التلسكوبات لكن لم يتم التقاطها.[4][5][6] أقمار زحل السبع كبيرة بما يكفي لانهيارها إلى شكل بيضاوي مسترخٍ، على الرغم من أن واحدًا أو اثنين فقط من هذه الأقمار، تيتان وربما ريا، هي حاليًا في حالة توازن هيدروستاتيكي. من بين أقمار زحل بشكل خاص تيتان، ثاني أكبر الأقمار في النظام الشمسي (بعد جانيميد قمر المشتري)، مع طقس غني بالنيتروجين شبيه بالغلاف الجوي للأرض ومناظر طبيعية تتميز بشبكات الأنهار الجافة وبحيرات الهيدروكربون،[7] وإنسيلادوس، الذي ينبعث منه نفاثات جليدية من منطقته القطبية الجنوبية ومغطى بطبقة عميقة من الثلج،[8] و إيابتوس، الذي يتميز بنصفيه المتباينين بالأبيض والأسود.

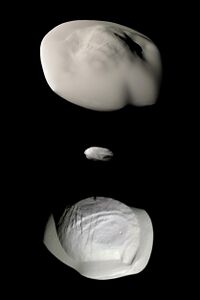

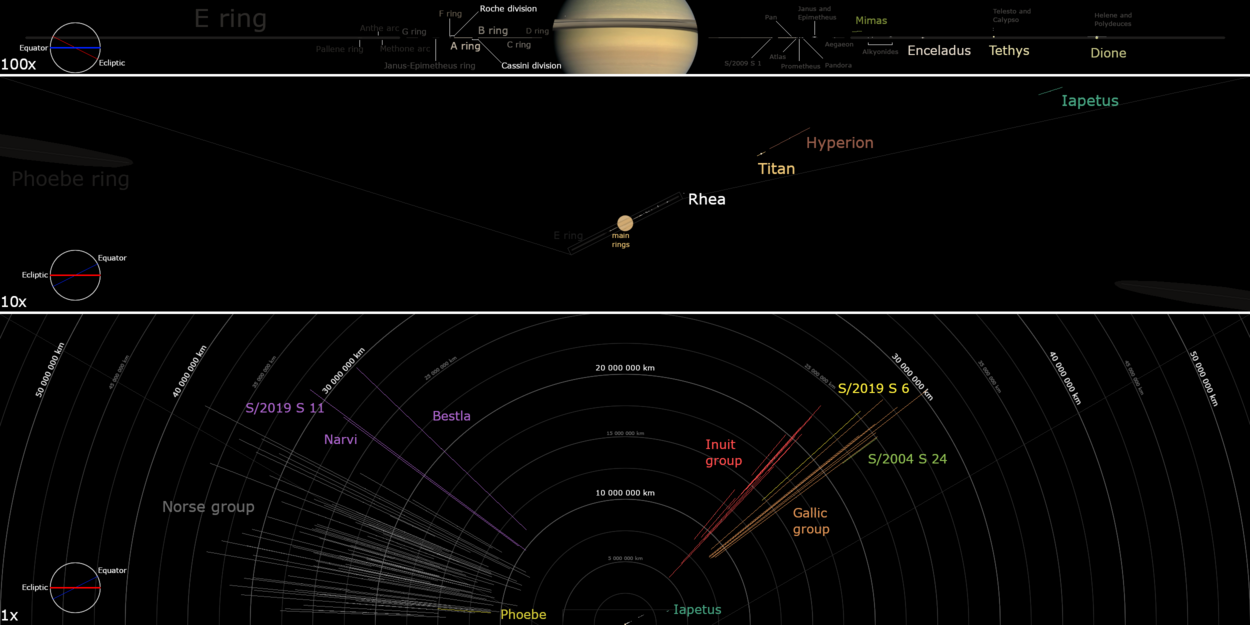

أربعة وعشرون من أقمار زحل هي "أقمار منتظمة"؛ ليس لديها مدار تقدمي يميل بقوة إلى مستوى زحل الاستوائي.[9] وهي تشمل الأقمار السبعة الرئيسية، وأربعة أقمار صغيرة موجودة في مدار طروادة مع أقمار أكبر، واثنان من الأقمار المدارية المشتركة، وقمرين يعملان كرعاة من الحلقة F الضيقة لزحل. هناك قمران آخران معروفان يدوران حول فجوات في حلقات زحل. هما قمر هايبرون نسبياً الذي يدور في رنين مداري مغلق مع تيتان. تدور الأقمار المنتظمة المتبقية بالقرب من الحافة الخارجية للحلقة A الكثيفة، داخل الحلقة G، وبين القمرين الرئيسيين ميماس وإنسيلادوس. سُميت الأقمار العادية باسم تيتان وتيتانسيس أو شخصيات أخرى مرتبطة بأسطورة زحل.

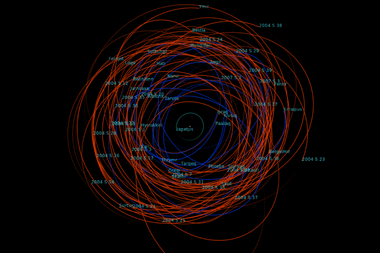

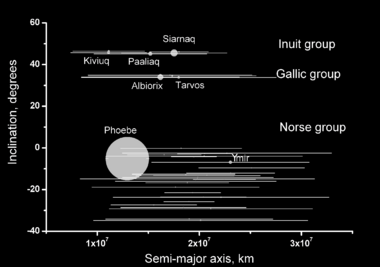

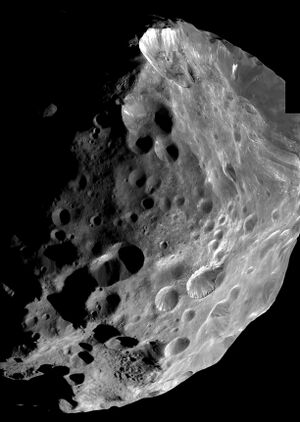

الأقمار الـ121 الباقية، بمتوسط قطر يتراوح بين 2-213 كم، هي أقمار غير نظامية، التي تكون مداراتها أبعد بكثير عن زحل، ولها ميول عالية، وتختلط بين التقدم والرجوع. من المحتمل أن تكون هذه الأقمار قد التقطتها كواكب صغيرة، أو أجزاء من اصطدام أدى إلى تفكك هذه الأجرام بعد التقاطها، مما أدى إلى تكون عائلات اصطدامية. من المتوقع أن يكون لزحل 130 قمراً غير نظامياً بقطر أكبر من 2.8 كم، بالإضافة إلى المئات الأخرى التي ربما تكون أصغر. تصنف الأقمار الغير نظامية بخصائصها المدارية إلى مجموعة إنويت، المجموعة الغالية المتقدمة، والمجموعة النوردية المتأخرة، وقد اختيرت أسمائها من الأساطير المتعلقة (حيث ترتبط المجموعة الجالية بالأساطير الكلتية). الاستثناء الوحيد هو فيبي، قمر زحل التاسع وأكبر قمر غير منتظم، تم اكتشافه في نهاية القرن التاسع عشر؛ وهو جزء من المجموعة النوردية لكنه سميت باسم تيتانيس اليونانية.

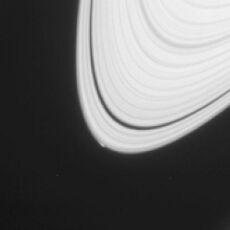

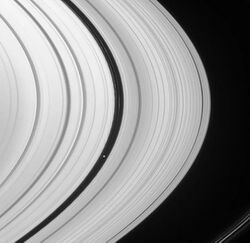

تتكون حلقات زحل من أجرام تتراوح في الحجم من المجهرية إلى الأقمار الصغرى التي يبلغ عرضها مئات الأمتار، كل منها في مداره الخاص حول زحل.[10] وبالتالي لا يمكن إعطاء عدد دقيق لأقمار زحل، لأنه لا توجد حدود موضوعية بين عدد لا يحصى من الأجرام المجهولة الصغيرة التي تشكل نظام حلقات زحل والأجرام الأكبر التي سميت أقمار. اكتشف أكثر من 150 قمرًا صغيرًا مدمجًا في الحلقات من خلال الاضطراب الذي تحدثه في مادة الحلقة المحيطة، على الرغم من أنه يُعتقد أن هذه ليست سوى عينة صغيرة من إجمالي عدد هذه الأجرام.[5]

اعتباراً من مايو 2023، كان هناك 81 قمراً غير مسمى خارج الحلقات، جميعها غير منتظمة. إذا تم تسميتها، فسيحصل معظمها على أسماء من الأساطير الجالية، النوردية وأساطير الإنويت استنادًا إلى المجموعة المدارية التي ينتمون إليها.[11][12]

الاكتشاف

عمليات الرصد المبكرة

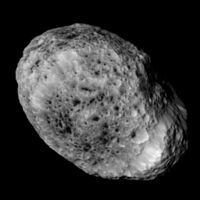

Before the advent of telescopic photography, eight moons of Saturn were discovered by direct observation using optical telescopes. Saturn's largest moon, Titan, was discovered in 1655 by Christiaan Huygens using a 57-millimeter (2.2 in) objective lens[13] on a refracting telescope of his own design.[14] Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus (the "Sidera Lodoicea") were discovered between 1671 and 1684 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini.[15] Mimas and Enceladus were discovered in 1789 by William Herschel.[15] Hyperion was discovered in 1848 by W. C. Bond, G. P. Bond[16] and William Lassell.[17]

The use of long-exposure photographic plates made possible the discovery of additional moons. The first to be discovered in this manner, Phoebe, was found in 1899 by W. H. Pickering.[18] In 1966 the tenth satellite of Saturn was discovered by Audouin Dollfus, when the rings were observed edge-on near an equinox.[19] It was later named Janus. A few years later it was realized that all observations of 1966 could only be explained if another satellite had been present and that it had an orbit similar to that of Janus.[19] This object is now known as Epimetheus, the eleventh moon of Saturn. It shares the same orbit with Janus—the only known example of co-orbitals in the Solar System.[20] In 1980, three additional Saturnian moons were discovered from the ground and later confirmed by the Voyager probes. They are trojan moons of Dione (Helene) and Tethys (Telesto and Calypso).[20]

عمليات الرصد بواسطة المركبات الفضائية

The study of the outer planets has since been revolutionized by the use of uncrewed space probes. The arrival of the Voyager spacecraft at Saturn in 1980–1981 resulted in the discovery of three additional moons—Atlas, Prometheus and Pandora—bringing the total to 17.[20] In addition, Epimetheus was confirmed as distinct from Janus. In 1990, Pan was discovered in archival Voyager images.[20]

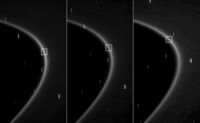

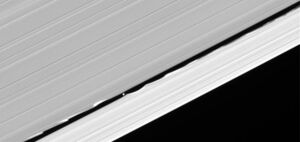

The Cassini mission,[21] which arrived at Saturn in July 2004, initially discovered three small inner moons: Methone and Pallene between Mimas and Enceladus, and the second trojan moon of Dione, Polydeuces. It also observed three suspected but unconfirmed moons in the F Ring.[22] In November 2004 Cassini scientists announced that the structure of Saturn's rings indicates the presence of several more moons orbiting within the rings, although only one, Daphnis, had been visually confirmed at the time.[23] In 2007 Anthe was announced.[24] In 2008 it was reported that Cassini observations of a depletion of energetic electrons in Saturn's magnetosphere near Rhea might be the signature of a tenuous ring system around Saturn's second largest moon.[25] In March 2009, Aegaeon, a moonlet within the G Ring, was announced.[26] In July of the same year, S/2009 S 1, the first moonlet within the B Ring, was observed.[27] In April 2014, the possible beginning of a new moon, within the A Ring, was reported.[28] (related image)

الأقمار الخارجية

Study of Saturn's moons has also been aided by advances in telescope instrumentation, primarily the introduction of digital charge-coupled devices which replaced photographic plates. For the 20th century, Phoebe stood alone among Saturn's known moons with its highly irregular orbit. Then in 2000, three dozen additional irregular moons were discovered using ground-based telescopes.[29] A survey starting in late 2000 and conducted using three medium-size telescopes found thirteen new moons orbiting Saturn at a great distance, in eccentric orbits, which are highly inclined to both the equator of Saturn and the ecliptic.[30] They are probably fragments of larger bodies captured by Saturn's gravitational pull.[29][30] In 2005, astronomers using the Mauna Kea Observatory announced the discovery of twelve more small outer moons,[31][32] in 2006, astronomers using the Subaru 8.2 m telescope reported the discovery of nine more irregular moons,[33] in April 2007, Tarqeq (S/2007 S 1) was announced and in May of the same year S/2007 S 2 and S/2007 S 3 were reported.[34] In 2019, twenty new irregular satellites of Saturn were reported, resulting in Saturn overtaking Jupiter as the planet with the most known moons for the first time since 2000.[12][4]

In 2019, researchers Edward Ashton, Brett Gladman, and Matthew Beaudoin conducted a survey of Saturn's Hill sphere using the 3.6-meter Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope and discovered about 80 new Saturnian irregular moons.[6][35] Follow-up observations of these new moons took place over 2019–2021, eventually leading to S/2019 S 1 being announced in November 2021 and an additional 62 moons being announced from 3–16 May 2023.[2][36] These discoveries brought Saturn's total number of confirmed moons up to 145, making it the first planet known to have over 100 moons.[2][1][37] Yet another moon, S/2006 S 20, was announced on 23 May 2023, bringing Saturn's total count moons to 146.[36] All of these new moons are small and faint, with diameters over 3 km (2 mi) and apparent magnitudes of 25–27.[6] The researchers found that the Saturnian irregular moon population is more abundant at smaller sizes, suggesting that they are likely fragments from a collision that occurred a few hundred million years ago. The researchers extrapolated that the true population of Saturnian irregular moons larger than 2.8 km (1.7 mi) in diameter amounts to 150±30, which is approximately three times as many Jovian irregular moons down to the same size. If this size distribution applies to even smaller diameters, Saturn would therefore intrinsically have more irregular moons than Jupiter.[6]

التسمية

The modern names for Saturnian moons were suggested by John Herschel in 1847.[15] He proposed to name them after mythological figures associated with the Roman god of agriculture and harvest, Saturn (equated to the Greek Cronus).[15] In particular, the then known seven satellites were named after Titans, Titanesses and Giants – brothers and sisters of Cronus.[18] The idea was similar to Simon Marius' mythological naming scheme for the moons of Jupiter.[38]

As Saturn devoured his children, his family could not be assembled around him, so that the choice lay among his brothers and sister, the Titans and Titanesses. The name Iapetus seemed indicated by the obscurity and remoteness of the exterior satellite, Titan by the superior size of the Huyghenian, while the three female appellations [Rhea, Dione, and Tethys] class together the three intermediate Cassinian satellites. The minute interior ones seemed appropriately characterized by a return to male appellations [Enceladus and Mimas] chosen from a younger and inferior (though still superhuman) brood. [Results of the Astronomical Observations made ... at the Cape of Good Hope, p. 415]

In 1848, Lassell proposed that the eighth satellite of Saturn be named Hyperion after another Titan.[17][38] When in the 20th century the names of Titans were exhausted, the moons were named after different characters of the Greco-Roman mythology or giants from other mythologies.[39] All the irregular moons (except Phoebe, discovered about a century before the others) are named after Inuit, and Gallic gods, and after Norse ice giants.[40]

Some asteroids share the same names as moons of Saturn: 55 Pandora, 106 Dione, 577 Rhea, 1809 Prometheus, 1810 Epimetheus, and 4450 Pan. In addition, three more asteroids would share the names of Saturnian moons but for spelling differences made permanent by the International Astronomical Union (IAU): Calypso and asteroid 53 Kalypso; Helene and asteroid 101 Helena; and Gunnlod and asteroid 657 Gunlöd.

الأحجام

| الاسم |

القطر (كم)[41] |

الكتلة (كج)[42] |

نصف القطر المداري (km)[43] |

الدور المداري (days)[43] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ميماس | 396 (0.12 D☾) |

4×1019 (0.0005 M☾) |

185,539 (0.48 a☾) |

0.9 (0.03 T☾) |

| إنسيلادوس | 504 (0.14 D☾) |

1.1×1020 (0.002 M☾) |

237,948 (0.62 a☾) |

1.4 (0.05 T☾) |

| تيثيس | 1,062 (0.30 D☾) |

6.2×1020 (0.008 M☾) |

294,619 (0.77 a☾) |

1.9 (0.07 T☾) |

| ديون | 1,123 (0.32 D☾) |

1.1×1021 (0.015 M☾) |

377,396 (0.98 a☾) |

2.7 (0.10 T☾) |

| ريا | 1,527 (0.44 D☾) |

2.3×1021 (0.03 M☾) |

527,108 (1.37 a☾) |

4.5 (0.20 T☾) |

| تيتان | 5,149 (1.48 D☾) (0.75 D♂) |

1.35×1023 (1.80 M☾) (0.21 M♂) |

1,221,870 (3.18 a☾) |

16 (0.60 T☾) |

| إيابتوس | 1,470 (0.42 D☾) |

1.8×1021 (0.025 M☾) |

3,560,820 (9.26 a☾) |

79 (2.90 T☾) |

المجموعات المدارية

أقمار الحلقات

أواخر يوليو 2009، اكتشف القمر الصغير S/2009 S 1، في الحلقة B، على بعد 48 كم من الحافة الخارجية للحلقة، بواسطة الظل الذي ألقاه.[27] يقدر قطره 300 متراً.على عكس الأقمار الصغيرة في الحلقة A (انظر أدناه)، فهو لا يستحث ميزة "المروحة"، ربما بسبب كثافة الحلقة B.[44]

الأقمار الحارسة

المدارات المشتركة

الكبرى الداخلية

ألكيونيدس

طروادة

الكبرى الخارجية

غير منتظمة

الإنويت

الغالية

النوردية

قائمة الأقمار

المؤكدة

| المفتاح | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♠ تيتان |

† أقمار محيطة أخرة |

أقمار منتظمة صغيرة |

‡ مجموعة إنويت |

♦ المجموعة الغالية |

♣ المجموعة النوردية |

§ أقمار غير منتظمة غير مجمعة |

| Label [أ] |

الاسم | النُطق | صورة | Abs. magn.[45] |

القطر (كم)[ب] |

الكتلة (×1015 كج)[ت] |

Semi-major axis (كم)[ث] |

Orbital period (d)[ث][ج] | Inclination (°)[ث][ح] |

Eccentricity | الموقع | سنة الاكتشاف[48] |

سنة الإعلان | المكتشف[39][48] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/2009 S 1 | — | — | 0.30 | < 0.00000001 | ≈ 117000 | ≈ 0.47150 | ≈ 0.000 | ≈ 0.0000 | الحلقة الخارجية B | 2009 | 2009 | كاسيني[27] | ||

| (الأقمار الصغيرة) | — | — | 0.04–0.4 | < 0.00000002 | ≈ 130000 | ≈ 0.55 | ≈ 0.000 | ≈ 0.0000 | Three 1,000 km bands within A Ring[5] | 2006 | — | كاسيني | ||

| XVIII | بان | /ˈpæn/ | 9.1 | 28.2 (34 × 31 × 20) |

5.0 | 133584 | +0.57505 | 0.000 | 0.0000 | in Encke Division | 1990 | 1990 | شوالتر | |

| XXXV | دافنيس | /ˈdæfnəs/ | 12.0 | 7.6 (8.6 × 8.2 × 6.4) |

0.077 | 136505 | +0.59408 | 0.004 | 0.0000 | in Keeler Gap | 2005 | 2005 | Cassini | |

| XV | أطلس | /ˈætləs/ | 10.7 | 30.2 (41 × 35 × 19) |

6.6 | 137670 | +0.60169 | 0.003 | 0.0012 | outer A Ring shepherd | 1980 | 1980 | Voyager 1 | |

| XVI | بروميثيوس | /proʊˈmiːθiəs/ | 6.5 | 86.2 (136 × 79 × 59) |

159.5 | 139380 | +0.61299 | 0.008 | 0.0022 | inner F Ring shepherd | 1980 | 1980 | Voyager 1 | |

| XVII | بنادورا | /pænˈdɔərə/ | 6.6 | 81.4 (104 × 81 × 64) |

137.1 | 141720 | +0.62850 | 0.050 | 0.0042 | outer F Ring shepherd | 1980 | 1980 | Voyager 1 | |

| XI | إبيمثيوس | /ɛpəˈmiːθiəs/ | 5.6 | 116.2 (130 × 114 × 106) |

526.6 | 151422 | +0.69433 | 0.335 | 0.0098 | co-orbital with Janus | 1966 | 1967 | Fountain & Larson | |

| X | جانوس | /ˈdʒeɪnəs/ | 4.7 | 179.0 (203 × 185 × 153) |

1897.5 | 151472 | +0.69466 | 0.165 | 0.0068 | co-orbital with Epimetheus | 1966 | 1967 | Dollfus | |

| LIII | آيجايون | /iːˈdʒiːɒn/ | 18.7 | 0.66 (1.4 × 0.5 × 0.4) |

≈ 0.000073 | 167500 | +0.80812 | 0.001 | 0.0004 | G Ring moonlet | 2008 | 2009 | Cassini | |

| I | †ميماس | /ˈmaɪməs/ | 2.7 | 396.4 (416 × 393 × 381) |

37493 | 185404 | +0.94242 | 1.566 | 0.0202 | 1789 | 1789 | Herschel | ||

| XXXII | ميثون | /məˈθoʊniː/ | 13.8 | 2.9 (3.9 × 2.6 × 2.4) |

≈ 0.0063 | 194440 | +1.00957 | 0.007 | 0.0001 | Alkyonides | 2004 | 2004 | Cassini | |

| XLIX | آنث | /ˈænθiː/ | 14.8 | 1.8 | ≈ 0.00026 | 197700 | +1.05089 | 0.100 | 0.0011 | Alkyonides | 2007 | 2007 | Cassini | |

| XXXIII | بالين | /pəˈliːniː/ | 12.9 | 4.4 (5.8 × 4.2 × 3.7) |

≈ 0.023 | 212280 | +1.15375 | 0.181 | 0.0040 | Alkyonides | 2004 | 2004 | Cassini | |

| II | †إنسيلادوس | /ɛnˈsɛlədəs/ | 1.8 | 504.2 (513 × 503 × 497) |

108022 | 237950 | +1.37022 | 0.010 | 0.0047 | Generates the E ring | 1789 | 1789 | Herschel | |

| III | †تيثيس | /ˈtiːθəs/ | 0.3 | 1062.2 (1077 × 1057 × 1053) |

617449 | 294619 | +1.88780 | 0.168 | 0.0001 | 1684 | 1684 | Cassini | ||

| XIV | كاليبسو | /kəˈlɪpsoʊ/ | 8.7 | 21.4 (30 × 23 × 14) |

≈ 2.5 | 294619 | +1.88780 | 1.473 | 0.0010 | trailing Tethys trojan ( ل5) | 1980 | 1980 | Pascu et al. | |

| XIII | تيليستو | /təˈlɛstoʊ/ | 8.7 | 24.8 (33 × 24 × 20) |

≈ 4.0 | 294619 | +1.88780 | 1.158 | 0.0010 | leading Tethys trojan ( ل4) | 1980 | 1980 | Smith et al. | |

| XXXIV | بوليديوسيس | /pɒliˈdjuːsiːz/ | 13.5 | 2.6 (3.0 × 2.4 × 1.0) |

≈ 0.0038 | 377396 | +2.73692 | 0.177 | 0.0192 | trailing Dione trojan ( ل5) | 2004 | 2004 | Cassini | |

| IV | †ديون | /daɪˈoʊniː/ | 0.4 | 1122.8 (1128 × 1123 × 1119) |

1095452 | 377396 | +2.73692 | 0.002 | 0.0022 | 1684 | 1684 | Cassini | ||

| XII | هيلين | /ˈhɛləniː/ | 7.3 | 35.2 (43 × 38 × 26) |

≈ 7.2 | 377396 | +2.73692 | 0.199 | 0.0022 | leading Dione trojan ( ل4) | 1980 | 1980 | Laques & Lecacheux | |

| V | †ريا | /ˈreɪə/ | –0.2 | 1527.6 (1530 × 1526 × 1525) |

2306518 | 527108 | +4.51821 | 0.327 | 0.0013 | 1672 | 1673 | Cassini | ||

| VI | ♠تيتان | /ˈtaɪtən/ | –1.3 | 5149.46 (5149 × 5149 × 5150) |

134520000 | 1221930 | +15.9454 | 0.349 | 0.0288 | 1655 | 1656 | Huygens | ||

| VII | هايبريون | /haɪˈpɪəriən/ | 4.8 | 270.0 (360 × 266 × 205) |

5619.9 | 1481010 | +21.2766 | 0.568 | 0.1230 | in 4:3 resonance with Titan | 1848 | 1848 | Bond & Lassell | |

| VIII | †إيابتوس | /aɪˈæpətəs/ | 1.7 | 1468.6 (1491 × 1491 × 1424) |

1805635 | 3560820 | +79.3215 | 15.47 | 0.0286 | 1671 | 1673 | Cassini | ||

| XXIV | ‡كيفيوك | /ˈkɪviək/ | 12.6 | ≈ 17 | ≈ 2.1 | 11111000 | +449.13 | 48.9 | 0.182 | Inuit group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| XXII | ‡إجيراك | /ˈiːɪrɒk/ | 13.2 | ≈ 13 | ≈ 0.90 | 11124000 | +451.46 | 49.2 | 0.353 | Inuit group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| ‡S/2019 S 1 | — | 15.3 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 11221100 | +445.60 | 46.7 | 0.541 | Inuit group | 2019 | 2021 | Ashton et al. | ||

| IX | ♣فيبي | /ˈfiːbi/ | 6.7 | 213.0 (219 × 217 × 204) |

8292.0 | 12929400 | −550.30 | 175.2 | 0.164 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 1898 | 1899 | Pickering | |

| XX | ‡بآلياك | /ˈpɑːliɒk/ | 11.9 | ≈ 25 | ≈ 5.6 | 14997300 | +687.08 | 47.1 | 0.384 | Inuit group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| XXVII | ♣سكاثي | /ˈskɑːði/ | 14.4 | ≈ 8 | ≈ 0.27 | 15575100 | −728.10 | 149.7 | 0.265 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| ♣S/2007 S 2 | — | 15.6 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 15939700 | −754.90 | 175.6 | 0.232 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2007 | 2007 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 37 | — | 15.9 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 15940500 | −754.47 | 159.3 | 0.446 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| XXVI | ♦ألبيوريكس | /ˌælbiˈɒrɪks/ | 11.2 | 28.6 | ≈ 12.2 | 16329100 | +783.49 | 38.9 | 0.470 | Gallic group | 2000 | 2000 | Holman | |

| XXXVII | ♦بيبهيون | /ˈbeɪvɪn/ | 15.0 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 17028900 | +834.94 | 37.4 | 0.482 | Gallic group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LX | ♦S/2004 S 29 | — | 15.8 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 17063900 | +837.78 | 38.6 | 0.485 | Gallic group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ‡S/2004 S 31 | — | 15.6 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 17495400 | +866.23 | 48.3 | 0.202 | Inuit group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| XXVIII | ♦إريابوس | /ɛriˈæpəs/ | 13.7 | ≈ 10 | ≈ 0.52 | 17507200 | +871.10 | 38.7 | 0.462 | Gallic group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| XLVII | ♣سكول | /ˈskɒl/ | 15.4 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.11 | 17625700 | −878.44 | 158.4 | 0.470 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LII | ‡تاركيك | /ˈtɑːrkeɪk/ | 14.8 | ≈ 6.5 | ≈ 0.18 | 17748200 | +884.98 | 49.7 | 0.119 | Inuit group | 2007 | 2007 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XXIX | ‡سيارناك | /ˈsiːɑːrnək/ | 10.6 | 39.3 | ≈ 31.8 | 17880800 | +895.87 | 48.2 | 0.311 | Inuit group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| XXI | ♦تارفوس | /ˈtɑːrvəs/ | 12.9 | ≈ 15 | ≈ 1.8 | 18215100 | +926.37 | 38.6 | 0.528 | Gallic group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| XLIV | ♣هيروكين | /hɪˈrɒkən/ | 14.3 | ≈ 8 | ≈ 0.27 | 18342600 | −931.89 | 150.3 | 0.331 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LI | ♣جريب | /ˈɡreɪp/ | 15.4 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.11 | 18424000 | −936.9 | 174.3 | 0.317 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ♣S/2004 S 13 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 18455800 | −942.59 | 168.9 | 0.266 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| XXV | ♣مونديلفاري | /mʊndəlˈværi/ | 14.5 | ≈ 7 | ≈ 0.18 | 18590300 | −952.95 | 168.4 | 0.210 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| ♣S/2006 S 1 | — | 15.6 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.065 | 18745600 | −964.15 | 155.2 | 0.105 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| LIV | ♣جريدر | /ˈɡriːðər/ | 15.7 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 19250700 | −1004.75 | 163.9 | 0.187 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XXXVIII | ♣بيرجلمير | /bɛərˈjɛlmɪər/ | 15.2 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 19269100 | −1005.58 | 158.7 | 0.144 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| L | ♣جارنساكسا | /jɑːrnˈsæksə/ | 15.6 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 19279700 | −1006.92 | 163.0 | 0.219 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XXXI | ♣نارفي | /ˈnɑːrvi/ | 14.5 | ≈ 7 | ≈ 0.18 | 19286500 | −1003.84 | 143.7 | 0.449 | Norse group | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XXIII | ♣ستونجر | /ˈsʊtʊŋɡər/ | 14.6 | ≈ 7 | ≈ 0.18 | 19391700 | −1016.71 | 175.0 | 0.116 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| ♣S/2004 S 17 | — | 16.0 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 19408100 | −1017.49 | 167.9 | 0.179 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2007 S 3 | — | 15.7 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.065 | 19513700 | −1026.35 | 175.6 | 0.162 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2007 | 2007 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| XLIII | ♣هاتي | /ˈhɑːti/ | 15.4 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 19697100 | −1040.29 | 164.1 | 0.375 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ♣S/2004 S 12 | — | 15.9 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 19770700 | −1046.13 | 163.0 | 0.325 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| LIX | ♣إجثر | /ˈɛɡθɛər/ | 15.4 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 19844700 | −1052.33 | 165.0 | 0.157 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XL | ♣فاربوتي | /fɑːrˈbaʊti/ | 15.8 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.065 | 20292500 | −1087.29 | 157.7 | 0.248 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XXX | ♣ثريمر | /ˈθrɪmər/ | 14.3 | ≈ 7 | ≈ 0.18 | 20326500 | −1091.84 | 174.8 | 0.467 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| XXXIX | ♣بستلا | /ˈbɛstlə/ | 14.6 | ≈ 7 | ≈ 0.18 | 20337900 | −1087.46 | 136.3 | 0.461 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ♣S/2004 S 7 | — | 15.6 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.065 | 20435200 | −1100.04 | 163.3 | 0.462 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| LV | ♣أنجربودا | /ˈɑːŋɡərboʊðə/ | 16.1 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 20591000 | −1114.05 | 177.4 | 0.216 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XXXVI | ♣آيجير | /ˈaɪ.ɪər/ | 15.5 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 20664600 | −1119.33 | 166.9 | 0.255 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LXI | ♣بيلي | /ˈbiːli/ | 16.1 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.014 | 20703800 | −1121.76 | 158.9 | 0.087 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LVII | ♣جيرد | /ˈjɛərð/ | 15.7 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 20947500 | −1142.97 | 174.4 | 0.517 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LXII | ♣جنلود | /ˈɡʊnlɒð/ | 15.5 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 21141900 | −1157.98 | 160.4 | 0.251 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ♣S/2006 S 3 | — | 15.5 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.065 | 21352700 | −1174.74 | 157.3 | 0.443 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| LVI | ♣سكريمير | /ˈskrɪmɪər/ | 15.6 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 21448000 | −1185.15 | 175.6 | 0.437 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ♣S/2004 S 28 | — | 15.8 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 21867800 | −1220.84 | 169.4 | 0.160 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| LXV | ♣ألفالدي | /ɔːlˈvɔːldi/ | 15.5 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 21995600 | −1232.19 | 177.4 | 0.238 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XLV | ♣كاري | /ˈkɑːri/ | 14.5 | ≈ 7 | ≈ 0.18 | 22029700 | −1231.01 | 153.0 | 0.482 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LXVI | ♣كيرود | /ˈjeɪrɒd/ | 15.8 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 22259500 | −1251.14 | 154.4 | 0.539 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XLI | ♣فنرير | /ˈfɛnrɪər/ | 15.9 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 22331800 | −1260.25 | 164.3 | 0.136 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XLVIII | ♣سورتور | /ˈsɜːrtər/ | 15.8 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 22753800 | −1296.49 | 168.3 | 0.449 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XLVI | ♣لوج | /ˈlɔɪ.eɪ/ | 15.3 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 22918300 | −1311.83 | 166.9 | 0.192 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XIX | ♣يمير | /ˈiːmɪər/ | 12.3 | ≈ 19 | ≈ 3.1 | 22957100 | −1315.16 | 173.1 | 0.337 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | |

| ♣S/2004 S 21 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 23125000 | −1325.32 | 155.0 | 0.409 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 39 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 2 | ≈ 0.0042 | 23195400 | −1336.16 | 167.1 | 0.102 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| §S/2004 S 24 | — | 16.0 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 23339900 | +1341.25 | 36.5 | 0.072 | Gallic group?[خ] | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 36 | — | 16.1 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 23433600 | −1353.23 | 152.5 | 0.617 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| LXIII | ♣ثيازي | /θiˈætsi/ | 15.9 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 23577500 | −1366.68 | 158.8 | 0.511 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LXIV | ♣S/2004 S 34 | — | 16.1 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 24145500 | −1420.77 | 168.3 | 0.279 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| XLII | ♣فورنجوت | /ˈfɔːrnjɒt/ | 15.1 | ≈ 6 | ≈ 0.11 | 24937300 | −1494.03 | 169.5 | 0.214 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | |

| LVIII | ♣S/2004 S 26 | — | 15.7 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 26097100 | −1603.95 | 172.9 | 0.148 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | |

| ‡S/2020 S 1 | — | 15.9 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 11339600 | +450.83 | 47.0 | 0.462 | Inuit group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2006 S 9 | — | 16.5 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 14453000 | −648.71 | 174.1 | 0.268 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2007 S 5 | — | 16.2 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 15899500 | −748.50 | 160.3 | 0.116 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 40 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 16145300 | −765.92 | 169.8 | 0.317 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 2 | — | 16.5 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 16568400 | −796.22 | 176.1 | 0.265 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 3 | — | 16.2 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 17125000 | −836.68 | 164.2 | 0.247 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2020 S 2 | — | 16.9 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 18071600 | −907.00 | 173.2 | 0.116 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ‡S/2020 S 3 | — | 16.4 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 17929800 | +896.35 | 47.1 | 0.038 | Inuit group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 4 | — | 16.5 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 17957200 | −898.40 | 169.5 | 0.450 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 41 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 17921900 | −895.76 | 168.3 | 0.295 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| §S/2020 S 4 | — | 17.0 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 18115900 | +910.34 | 43.4 | 0.389 | ? | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ‡S/2020 S 5 | — | 16.6 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 18422200 | +933.52 | 49.4 | 0.135 | Inuit group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2007 S 6 | — | 16.4 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 18563700 | −944.31 | 165.8 | 0.172 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 42 | — | 16.1 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 18119500 | −910.61 | 165.8 | 0.157 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2006 S 10 | — | 16.4 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 18837300 | −965.26 | 161.5 | 0.154 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 5 | — | 16.6 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 18919000 | −971.54 | 155.6 | 0.183 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 43 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 18918200 | −971.48 | 172.0 | 0.390 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 44 | — | 15.8 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 19478800 | −1014.98 | 169.0 | 0.129 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 45 | — | 16.0 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20037400 | −1058.95 | 150.1 | 0.464 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2006 S 11 | — | 16.5 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 19523200 | −1018.45 | 172.0 | 0.137 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♦S/2006 S 12 | — | 16.2 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 19837600 | +1043.16 | 39.0 | 0.485 | Gallic group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| §S/2019 S 6 | — | 16.1 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 19996100 | +1055.68 | 46.3 | 0.193 | ? | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2006 S 13 | — | 16.1 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20072600 | −1061.74 | 164.8 | 0.273 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 7 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20475400 | −1093.86 | 172.9 | 0.247 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 8 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20309500 | −1080.60 | 173.9 | 0.301 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 9 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20605100 | −1104.27 | 161.7 | 0.345 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 46 | — | 16.4 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20213900 | −1072.97 | 176.0 | 0.229 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 10 | — | 16.7 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 20918200 | −1129.53 | 161.2 | 0.268 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2004 S 47 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 16001242 | −755.69 | 159.7 | 0.286 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 11 | — | 16.2 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20518700 | −1097.33 | 150.6 | 0.577 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2006 S 14 | — | 16.5 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 19837600 | −1150.64 | 164.4 | 0.056 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 12 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 20928900 | −1130.40 | 166.9 | 0.534 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2020 S 6 | — | 16.6 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 21159200 | −1149.11 | 169.3 | 0.428 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 13 | — | 16.7 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 20959700 | −1132.90 | 178.6 | 0.377 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ‡S/2005 S 4 | — | 15.7 | ≈ 5 | ≈ 0.11 | 11302600 | +448.63 | 52.5 | 0.177 | Inuit group | 2005 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2007 S 7 | — | 16.2 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 15818700 | −742.79 | 169.3 | 0.232 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♦S/2007 S 8 | — | 16.0 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 16991800 | +826.94 | 37.8 | 0.535 | Gallic group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| ♣S/2020 S 7 | — | 16.8 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 17236300 | −844.85 | 160.8 | 0.558 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ‡S/2019 S 14 | — | 16.3 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 18005000 | +902.00 | 50.1 | 0.072 | Inuit group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2019 S 15 | — | 16.6 | ≈ 3 | ≈ 0.014 | 21246200 | −1156.21 | 157.6 | 0.254 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| ♣S/2005 S 5 | — | 16.4 | ≈ 4 | ≈ 0.034 | 21030100 | −1138.62 | 172.5 | 0.510 | Norse group | 2005 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. |

الغير مؤكدة

| الاسم | صورة | القطر (كم) | Semi-major المحور (كم)[46] |

الدور المداري (ي)[46] |

الموقع | سنة الاكتشاف | الحالة |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/2004 S 3 وS 4[د] |  |

≈ 3–5 | ≈ 140300 | ≈ +0.619 | uncertain objects around the F Ring | 2004 | Were undetected in thorough imaging of the region in November 2004, making their existence improbable |

| S/2004 S 6 |  |

≈ 3–5 | ≈ 140130 | +0.61801 | 2004 | Consistently detected into 2005, may be surrounded by fine dust and have a very small physical core |

زائفة

افتراضية

مؤقتة

التكوين

مقارنة بكواكب أخرى

في 13 مايو 2023، قال سكوت شيبارد، عالم الفلك من معهد كارنيجي للعلوم في واشنطن دي سي، "كلاهما لديه الكثير والكثير من الأقمار ، لكن زحل "يبدو أنه يمتلك أقمارًا أكثر بكثير" لأسباب غير مفهومة تمامًا.

لا تشبه أقمار زحل المكتشفة حديثًا الجسم اللامع في سماء الأرض ليلاً. هيي غير منتظمة الشكل، مثل حبة البطاطس، ولا يزيد عرضها عن ميل أو ميلين. هم يدورون بعيدًا عن الكوكب أيضًا، ما بين ستة ملايين و18 مليون ميل، مقارنة بالأقمار الأكبر، مثل تيتان، التي تدور في الغالب على بعد مليون ميل من زحل. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه الأقمار الصغيرة غير المنتظمة رائعة بحد ذاتها. تتجمع في الغالب معًا في مجموعات، وقد تكون بقايا أقمار أكبر تحطمت أثناء دورانها حول زحل.[49]

قالت بوني بوراتي من مختبر الدفع النفاث التابع لوكالة ناسا في كاليفورنيا ونائبة عالم المشروع في مهمة أوروبا كليبر القادمة إلى كوكب المشتري: "هذه الأقمار أساسية جدًا لفهم بعض الأسئلة الكبيرة حول النظام الشمسي". مضيفة: "إنها تحمل بصمات الأحداث التي وقعت في النظام الشمسي المبكر."

يسلط العدد المتزايد من الأقمار الضوء أيضًا على النقاشات المحتملة حول ما يشكله القمر. قال د. شيبارد: "التعريف البسيط للقمر هو أنه جرم يدور حول كوكب. حجم الجرم، في الوقت الحالي، لا يهمط.

اكتشفت الأقمار الجديدة من قبل مجموعتين، إحداهما بقيادة الدكتور شيبارد والأخرى بقيادة إدوارد أشتون من معهد أكاديميا سينيكا لعلم الفلك والفيزياء الفلكية في تايوان. استخدمت مجموعة د. شيبارد، في منتصف عام 2000، تلسكوب سوبارو في هاواي للبحث عن المزيد من الأقمار حول زحل.

في مارس، كان د. شيبارد مسؤولاً أيضًا عن العثور على 12 قمراً جديداً لكوكب المشتري، مما جعل الكوكب أكبر مكتنز للأقمار. إلا أن هذا السبق استمر لوقت قصير.

استخدمت مجموعة د. أشتون، من عام 2019 إلى عام 2021، تلسكوب كندا-فرانس-هاواي، أحد جيران تلسكوب سوبارو على ماونا كيا، للبحث عن المزيد من أقمار زحل والتحقق من بعض اكتشافات د. شيبارد. من أجل مصادقة القمر، يجب رصده عدة مرات "للتأكد من أن الملاحظات عبارة عن ساتل وليس مجرد كويكب يقع بالقرب من الكوكب"، كما قال مايك ألكسندرسن، المسؤول عن تأكيد الأقمار رسميًا في الاتحاد الفلكي الدولي.

تدور معظم أقمار زحل غير المنتظمة حول الكوكب فيما يسميه علماء الفلك مجموعات الإنويت والإسكندنافية والغالية. قد تكون كائنات كل مجموعة بقايا أقمار أكبر، يصل قطرها إلى 150 ميلًا، والتي كانت تدور في يوم من الأيام حول زحل ولكنها دمرت بسبب اصطدامات من الكويكبات أو المذنبات، أو الاصطدامات بين قمرين. قال د. شيبارد: "إنه يظهر أن هناك تاريخ تصادم كبير حول هذه الكواكب".

قال د. أشتون إن هذه الأقمار الأصلية ربما تكون قد التقطت من قبل زحل "في وقت مبكر جدًا من النظام الشمسي"، ربما في بضع مئات الملايين من السنين الأولى بعد تكوينه قبل 4.5 مليار سنة. ومع ذلك، لا تدور كل هذه المجموعات في مدار مع عدد قليل من الأقمار المارقة التي تدور في اتجاه رجعي - أي عكس مدارات الأقمار الأخرى.

قال د. شيبارد: "لا نعرف ما الذي يحدث مع تلك الأقمار المتراجعة". يشتبه د. أشتون في أنهما قد تكونان بقايا اصطدام أحدث.

من الصعب معرفة المزيد عن الأقمار الجديدة بسبب صغر حجمها ومداراتها البعيدة. يبدو أنها فئة خاصة من الأجسام ، تختلف عن الكويكبات التي تشكلت في النظام الشمسي الداخلي والمذنبات في النظام الشمسي الخارجي. لكن لا يعرف الكثير. قال د. شيبارد: "قد تكون هذه الأجرام فريدة". "قد تكون البقايا الأخيرة لما تشكل في منطقة الكوكب العملاق، من المحتمل أن تكون أجراماً غنية جدًا بالجليد."

تمكنت المركبة الفضائية كاسيني التابعة لناسا من رصد حوالي عشرين من الأقمار حول زحل حتى تقاعدها عام 2017. وعلى الرغم من أنها ليست قريبة بما يكفي للدراسة بالتفصيل، إلا أن البيانات سمحت للعلماء "بتحديد فترة الدوران" لبعض الأقمار، قال تيلمان دينك من مركز الفضاء الألماني في برلين، الذي قاد عمليات الرصد: محور الدوران وحتى الشكل. عثرت كاسيني أيضًا على جليد وفير على سطح أحد أكبر الأقمار غير المنتظمة، فيبي.

يمكن أن تعطي الملاحظات الدقيقة لأقمار زحل الصغيرة فرصة للعلماء للدخول في وقت مضطرب في النظام الشمسي المبكر. خلال تلك الفترة، كانت الاصطدامات أكثر شيوعًا وتزاحمت الكواكب للحصول على موقع، ويعتقد أن المشتري قد هاجر من أقرب الشمس إلى مداره الحالي. قال د. دينك: "يمنحك هذا معلومات إضافية حول تكوين النظام الشمسي".

ومع ذلك، فإن الأقمار غير المنتظمة التي نراها حتى الآن قد تكون البداية فقط. قال د. أشتون: "قدرنا أن هناك الآلاف المحتملة" حول زحل والمشتري. قد يكون لأورانوس ونبتون أيضًا العديد من هذه الأقمار غير المنتظمة، لكن المسافة الشاسعة بينهما من الشمس تجعل من الصعب اكتشافها.

يبدو أن زحل، على الرغم من كونه أصغر من كوكب المشتري، يحتوي على عدد أكبر من الأقمار غير المنتظمة. قد يكون حجمه ثلاثة أضعاف حجم كوكب المشتري، إلى حوالي ميلين في الحجم. قال د. أشتون إن السبب غير واضح.

ربما تميل أقمار المشتري الأصلية إلى أن تكون أكبر وأقل عرضة للإنشقاق. أو ربما يكون زحل قد التقط المزيد من الأجرام في مداره أكثر من كوكب المشتري. أو ربما كانت أقمار زحل تدور في مدارات من المرجح أن تتداخل وتتصادم، مما ينتج أقمارًا أصغر غير منتظمة.

مهما كان السبب، فإن النتيجة واضحة. كوكب المشتري على وشك الانهيار، ومن غير المرجح أن يستعيد لقبه باعتباره الكوكب الذي يضم أكبر عدد من الأقمار.

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ A confirmed moon is given a permanent designation by the IAU consisting of a name and a Roman numeral.[39] The eight moons that were known before 1850 are numbered in order of their distance from Saturn; the rest are numbered in the order by which they received their permanent designations. Many small moons have not yet received a permanent designation.

- ^ The diameters and dimensions of the inner moons from Pan through Janus, Methone, Pallene, Telepso, Calypso, Helene, Hyperion and Phoebe were taken from Thomas 2010, Table 3.[41] Diameters and dimensions of Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus are from Thomas 2010, Table 1.[41] The approximate sizes of other satellites are from the website of Scott Sheppard.[4]

- ^ Masses of the large moons were taken from Jacobson, 2006.[42] Masses of Pan, Daphnis, Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Epimetheus, Janus, Hyperion and Phoebe were taken from Thomas, 2010, Table 3.[41] Masses of small regular satellites were calculated assuming a density of 0.5 جم/سم3, while masses of irregular satellites were calculated assuming a density of 1.0 g/cm3.

- ^ أ ب ت The orbital parameters were taken from Spitale et al. 2006,[46] IAU-MPC Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service,[45] JPL Solar System Dynamics,[47] and NASA/NSSDC.[43]

- ^ Negative orbital periods indicate a retrograde orbit around Saturn (opposite to the planet's rotation). Orbital periods of irregular satellites may not be consistent with their semi-major axes due to perturbations.

- ^ To Saturn's equator for the regular satellites, and to the ecliptic for the irregular satellites.

- ^ May be part of the Gallic group, inclination is similar but semi-major axis is not

- ^ S/2004 S 4 was most likely a transient clump—it has not been recovered since the first sighting.[22]

المصادر

- ^ أ ب O'Callaghan, Jonathan (12 May 2023). "With 62 Newly Discovered Moons, Saturn Knocks Jupiter Off Its Pedestal - If all the objects are recognized by scientific authorities, the ringed giant world will have 145 moons in its orbit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2023. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "NYT-20230512" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب ت "Saturn now leads moon race with 62 newly discovered moons". UBC Science. University of British Columbia. 11 May 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ "MPEC 2023-J85 : S/2005 S 5". Minor Planet Electronic Circulars. Minor Planet Center. 10 May 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت Sheppard, Scott S. "Moons of Saturn". Earth & Planets Laboratory. Carnegie Institution for Science. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Burns, J.A; Hedman, M.M; Porco, C.C (2008). "The population of propellers in Saturn's A Ring". Astronomical Journal. 135 (3): 1083–1091. arXiv:0710.4547. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1083T. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/1083. S2CID 28620198.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew (August 2021). "Evidence for a Recent Collision in Saturn's Irregular Moon Population". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (4): 12. Bibcode:2021PSJ.....2..158A. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac0979. S2CID 236974160.

- ^ Redd, Nola Taylor (27 March 2018). "Titan: Facts About Saturn's Largest Moon". Space.com. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Enceladus - Overview - Planets - NASA Solar System Exploration". Archived from the original on 2013-02-17.

- ^ "Moons".

- ^ Esposito, L. W. (2002). "Planetary rings". Reports on Progress in Physics. 65 (12): 1741–1783. Bibcode:2002RPPh...65.1741E. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/65/12/201. S2CID 250909885.

- ^ "Help Name 20 Newly Discovered Moons of Saturn!". Carnegie Science. 7 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ أ ب "Saturn Surpasses Jupiter After The Discovery Of 20 New Moons And You Can Help Name Them!". Carnegie Science. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Nemiroff, Robert & Bonnell, Jerry (March 25, 2005). "Huygens Discovers Luna Saturni". Astronomy Picture of the Day. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Baalke, Ron. "Historical Background of Saturn's Rings (1655)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Van Helden, Albert (1994). "Naming the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn" (PDF). The Newsletter of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society (32): 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-14.

- ^ Bond, W.C (1848). "Discovery of a new satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 9: 1–2. Bibcode:1848MNRAS...9....1B. doi:10.1093/mnras/9.1.1.

- ^ أ ب Lassell, William (1848). "Discovery of new satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8 (9): 195–197. Bibcode:1848MNRAS...8..195L. doi:10.1093/mnras/8.9.195a.

- ^ أ ب Pickering, Edward C (1899). "A New Satellite of Saturn". Astrophysical Journal. 9 (221): 274–276. Bibcode:1899ApJ.....9..274P. doi:10.1086/140590. PMID 17844472.

- ^ أ ب Fountain, John W; Larson, Stephen M (1977). "A New Satellite of Saturn?". Science. 197 (4306): 915–917. Bibcode:1977Sci...197..915F. doi:10.1126/science.197.4306.915. PMID 17730174. S2CID 39202443.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Uralskaya, V.S (1998). "Discovery of new satellites of Saturn". Astronomical and Astrophysical Transactions. 15 (1–4): 249–253. Bibcode:1998A&AT...15..249U. doi:10.1080/10556799808201777.

- ^ Corum, Jonathan (December 18, 2015). "Mapping Saturn's Moons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ أ ب Porco, C. C.; Baker, E.; Barbara, J.; et al. (2005). "Cassini Imaging Science: Initial Results on Saturn's Rings and Small Satellites" (PDF). Science. 307 (5713): 1226–36. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1226P. doi:10.1126/science.1108056. PMID 15731439. S2CID 1058405.

- ^ Robert Roy Britt (2004). "Hints of Unseen Moons in Saturn's Rings". Space.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Porco, C.; The Cassini Imaging Team (July 18, 2007). "S/2007 S4". IAU Circular. 8857.

- ^ Jones, G.H.; Roussos, E.; Krupp, N.; et al. (2008). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea". Science. 319 (1): 1380–84. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J. doi:10.1126/science.1151524. PMID 18323452. S2CID 206509814.

- ^ Porco, C.; The Cassini Imaging Team (March 3, 2009). "S/2008 S1 (Aegaeon)". IAU Circular. 9023.

- ^ أ ب ت Porco, C. & the Cassini Imaging Team (November 2, 2009). "S/2009 S1". IAU Circular. 9091.

- ^ Platt, Jane; Brown, Dwayne (14 April 2014). "NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ أ ب Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007). "Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 45 (1): 261–95. arXiv:astro-ph/0703059. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..261J. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459. S2CID 13282788. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19.

- ^ أ ب Gladman, Brett; Kavelaars, J. J.; Holman, Matthew; et al. (2001). "Discovery of 12 satellites of Saturn exhibiting orbital clustering". Nature. 412 (6843): 1631–166. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..163G. doi:10.1038/35084032. PMID 11449267. S2CID 4420031.

- ^ David Jewitt (May 3, 2005). "12 New Moons For Saturn". University of Hawaii. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Emily Lakdawalla (May 3, 2005). "Twelve New Moons For Saturn". Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D. C. & Kleyna, J. (يونيو 30, 2006). "Satellites of Saturn". IAU Circular. 8727. Archived from the original on فبراير 13, 2010. Retrieved يناير 2, 2010.

- ^ Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D. C. & Kleyna, J. (مايو 11, 2007). "S/2007 S 1, S/2007 S 2, AND S/2007 S 3". IAU Circular. 8836: 1. Bibcode:2007IAUC.8836....1S. Archived from the original on فبراير 13, 2010. Retrieved يناير 2, 2010.

- ^ Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew; Alexandersen, Mike; Petit, Jean-Marc (May 2022). "Discovery of the Closest Saturnian Irregular Moon, S/2019 S 1, and Implications for the Direct/Retrograde Satellite Ratio". The Astronomical Journal. 3 (5): 5. Bibcode:2022PSJ.....3..107A. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac64a2. S2CID 248771843. 107.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMPEC-2023-K118 - ^ Semeniuk, Ivan (14 May 2023). "Astronomers discover record-breaking 62 moons around Saturn". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 30 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ أ ب van Helden, Albert (August 1994). "Naming the Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn" (PDF). The Newsletter of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society (32). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Grav, Tommy; Bauer, James (2007). "A deeper look at the colors of the Saturnian irregular satellites". Icarus. 191 (1): 267–285. arXiv:astro-ph/0611590. Bibcode:2007Icar..191..267G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.04.020. S2CID 15710195.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Thomas, P. C. (July 2010). "Sizes, shapes, and derived properties of the saturnian satellites after the Cassini nominal mission" (PDF). Icarus. 208 (1): 395–401. Bibcode:2010Icar..208..395T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.01.025.

- ^ أ ب Jacobson, R. A.; Antreasian, P. G.; Bordi, J. J.; Criddle, K. E.; Ionasescu, R.; Jones, J. B.; Mackenzie, R. A.; Meek, M. C.; Parcher, D.; Pelletier, F. J.; Owen, Jr., W. M.; Roth, D. C.; Roundhill, I. M.; Stauch, J. R. (December 2006). "The Gravity Field of the Saturnian System from Satellite Observations and Spacecraft Tracking Data". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (6): 2520–2526. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.2520J. doi:10.1086/508812.

- ^ أ ب ت Williams, David R. (August 21, 2008). "Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ "A Small Find Near Equinox". NASA/JPL. August 7, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-10. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ أ ب "Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 22 January 2023. Selection of Objects → "All Jovian outer irregular satellites" → Check "I require Orbital Elements" → Get Information

- ^ أ ب ت Spitale, J. N.; Jacobson, R. A.; Porco, C. C.; Owen, W. M. Jr. (2006). "The orbits of Saturn's small satellites derived from combined historic and Cassini imaging observations". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (2): 692–710. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..692S. doi:10.1086/505206. S2CID 26603974.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةjplsats - ^ أ ب "Planetary Satellite Discovery Circumstances". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 15 November 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "With 62 Newly Discovered Moons, Saturn Knocks Jupiter Off Its Pedestal". نيويورك تايمز. 2023-05-13. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Asphaug2013" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Hedman2007" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Porco2007" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Thomas2007" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Sremcevic2007" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Tiscareno2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Giese2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Thomas2007b" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Thomas1995" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Moore Schenk et al. 2004" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Porco Helfenstein et al. 2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Pontius2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Wagner2008" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Porco2005b" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Verbiscer2009" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Porco2005c" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Lopes2007" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Lorenz2006" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Stofan2007" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Schenk2009" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Wagner2009" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Schenk2009b" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Alkyonides" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Murray2008" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "KrakenMare" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Solarviews" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Inktomi" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Splat" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

<ref> ذو الاسم "Zebker 2009" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.وصلات خارجية

- Scott S. Sheppard: Saturn Moons

- "Simulation showing the position of Saturn's Moon". Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- "Saturn's Rings". NASA's Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- "Saturn's Moons". Astronomy Cast episode No. 61, includes full transcript. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- Carolyn Porco. Fly me to the moons of Saturn. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- Rotate and Spin Maps of 7 Moons at The New York Times

- Planetary Society blog post (2017-05-17) by Emily Lakdawalla with images giving comparative sizes of the moons

- Tilmann Denk: Outer Moons of Saturn