حزب الاشتراكية الديمقراطية (ألمانيا)

حزب الاشتراكية الديمقراطية Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus / Die Linkspartei.PDS | |

|---|---|

| |

| الاختصار | PDS |

| الزعيم | Lothar Bisky |

| تأسس |

|

| انحل | 16 June 2007 |

| سبقه | Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) |

| اندمج في | The Left |

| المقر الرئيسي | Karl-Liebknecht-Haus Kleine Alexanderstraße 28 D-10178 Berlin |

| الأيديولوجية | |

| الموقف السياسي | Left-wing[10] |

| الانتماء الاوروپي | Party of the European Left |

| الجماعة بالپرلمان الاوروپي | European United Left–Nordic Green Left |

| الألوان | Red |

| الموقع | |

| www.sozialisten.de | |

حزب الاشتراكية الديمقراطية (ألمانية: Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus, PDS) was a left-wing populist political party in Germany active between 1989 and 2007.[11] It was the legal successor to the communist Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), which ruled the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) as the de facto sole legal party until 1990.[12] From 1990 through to 2005, the PDS had been seen as the left-wing "party of the East". While it achieved minimal support in western Germany, it regularly won 15% to 25% of the vote in the eastern new states of Germany, entering coalition governments with the Social Democratic Party of Germany in the federal states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Berlin.[13]

In 2005, the PDS, renamed The Left Party.PDS (Die Linkspartei.PDS) entered an electoral alliance with the Western Germany-based Electoral Alternative for Labour and Social Justice (WASG) and won 8.7% of the vote in Germany's September 2005 federal elections (more than double the 4% share achieved by the PDS alone in the 2002 federal election). On 16 June 2007, the two groupings merged to form a new party called The Left (Die Linke).[14]

The party had many socially progressive policies, including support for legalisation of same-sex marriage and greater social welfare for immigrants.[15]

Internationally, the Left Party.PDS was a co-founder of the Party of the European Left and was the largest party in the European United Left–Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) group in the European Parliament.[14]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

Fall of communism

On 18 October 1989, longtime East German leader Erich Honecker was forced to resign from his post of General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), under pressure from both civil rights movements in the German Democratic Republic and the party base itself. He was replaced by Egon Krenz, who was not, however, able to stop the collapse of the party and the government. On 9 November 1989 the Berlin Wall fell, borders between East and West Germany were reopened and on 1 December 1989 the Volkskammer abrogated the constitutional provisions that gave the SED a monopoly of power in the GDR.[16]

On 3 December 1989, Krenz and the entire SED politburo resigned and were all expelled from the party by the central committee, which in turn dissolved itself soon after that.[16] This empowered a younger generation of reform politicians in East Germany's ruling socialist class, who looked to Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika as their model for political change.[17] Reformers like authors Stefan Heym and Christa Wolf and attorney Gregor Gysi, lawyer of dissidents like Robert Havemann and Rudolf Bahro, soon began to re-invent a party infamous for its rigid Marxist–Leninist orthodoxy and police-state methods.[12]

A special party congress convened in the Dynamo-Sporthalle in East Berlin on 8–9 December 1989 and elected Gregor Gysi as new party Chairman, along Hans Modrow and Wolfgang Berghofer as his deputies.[18] By the time of a special party conference on 16 December 1989, it was obvious that the SED was no longer a Marxist-Leninist party. During the second session the party accepted a proposal from Gysi that the party adopt a new name, "Party of Democratic Socialism". Gysi felt a name change was necessary to distance the reformed party from its repressive past. The proposal came directly after a speech from Michael Schumann highlighting the injustices perpetrated under the SED, and distancing the conference from certain high-profile party leaders – notably Honecker and the country's last Communist leader, Egon Krenz. Above all Schumann's speech opened the way for the party to reinvent itself, using a phrase that was later much quoted: "We break irrevocably with Stalinism as a system!"[19][20] A brief transitional period followed, during which the party was named "Socialist Unity Party of Germany - Party of Democratic Socialism" (SED - PDS).

By the end of 1989, the last hardline members of the party's Central Committee had either resigned or been pushed out; meanwhile, by 1990, 95% of the SED's 2.3 million members had left the party. On 4 February 1990, the party was formally renamed the PDS. However, neo-Marxist and communist minority factions continued to exist.[21] By the time the party had formally renamed itself into Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and had expelled most of the remaining prominent Communist-era leaders from its ranks—including Honecker and Krenz.[22] Meanwhile, a faction of hardline Marxists-Leninists opposing reforms had split away from the party and had re-established the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which included Erich and Margot Honecker in its ranks.[23]

This was not enough to save the party when it faced the voters for the first time in the 1990 East German elections—the first and only free elections held in East Germany. The party was roundly defeated, winning only 66 seats in the 400-seat Volkskammer, finishing a distant third behind the East German wings of the Christian Democratic Union and the recently refounded Social Democratic Party.[24]

ألمانيا المعاد توحيدها

In the first all-German elections in 1990, the PDS won only 2.4% of the nationwide vote. However, a one-time exception to Germany's electoral law allowed eastern-based parties to qualify for representation if they won five percent of the vote in the former East Germany. As a result, the PDS entered the Bundestag with 17 deputies led by Gysi. However, it was only reckoned as a "group" within the Bundestag, and not a full-fledged parliamentary faction.

In the 1994 federal election, in spite of an anti-communist "Red Socks" campaign by the then-ruling Christian Democrats aimed at scaring off eastern voters,[25] the PDS increased its vote to 4.4%. More importantly, Gysi was reelected from his Berlin seat, and three other PDS members were elected from districts in the former East Berlin, the party's power base. Under a provision of the German constitution intended to benefit regional parties, a party that wins at least three directly-elected seats is eligible for proportional representation, even if it falls short of the five percent threshold. This allowed it to re-enter the Bundestag with an enlarged caucus of 30 deputies. In the 1998 federal election, the party reached the high-water mark in its fortunes by tallying 5.1% of the national vote and 36 seats, thus clearing the critical 5% threshold required for guaranteed proportional representation and full parliamentary status in the Bundestag.

The party's future seemed bright, but it suffered from a number of weaknesses, not the least of which was its dependence on Gysi, considered by supporters and critics alike as a super-star in German politics who stood in stark contrast to a colourless general membership. Gysi's resignation in 2000 after losing a policy debate with party leftists soon spelled trouble for the PDS. In the 2002 federal election, the party's vote sank back to 4.0%, and was able to seat only two back-benchers elected directly from their districts, Petra Pau and Gesine Lötzsch.

After the 2002 debacle, the PDS adopted a new programme and re-installed a respected moderate, long-time Gysi ally Lothar Bisky, as chair. A renewed sense of self-confidence soon re-energised the party. In the 2004 elections to the European Parliament, the PDS won 6.1% of the vote nationwide, its highest total at that time in a federal election. Its electoral base in the eastern German states continued to grow, where it ranked with the CDU and SPD one of the region's three strong parties. However, low membership and voter support in Germany's western states continued to plague the party on the federal level until it formed an electoral alliance in July 2005 with Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative (WASG), a leftist faction of dissident Social Democrats and trade unionists which had split away from the SPD some months prior, with the merged list being called the Left Party. In the 2005 federal election the Left Party received 8.7% of the nationwide vote and won 54 seats in the German Bundestag.

التحالف مع WASG

After marathon negotiations, the PDS and WASG agreed on terms for a combined ticket to compete in the 2005 federal election and pledged to unify into a single left-wing party in 2006 or 2007. According to the pact, the parties did not compete against each another in any district. Instead, WASG candidates—including the former SPD leader, Oskar Lafontaine—were nominated on the PDS electoral list. To symbolize the new relationship, the PDS changed its name to The Left Party/PDS or The Left/PDS, with the letters "PDS" optional in western states where many voters still regarded the PDS as an "eastern" party.

The alliance provided a strong electoral base in the east and benefited from WASG's growing voter potential in the west. Gregor Gysi, returning to public life only months after brain surgery and two heart attacks, shared the spotlight with Lafontaine as co-leader of the party's energetic and professional campaign. Both politicians co-chaired The Left's caucus in the German Bundestag after the election.

Polls early in the summer[when?] showed the unified Left list on a "high-altitude flight", winning as much as 12% of the vote, and for a time it seemed possible the party would surge past the Alliance '90/The Greens and the pro-business Free Democratic Party and become the third-strongest force in the Bundestag. But, alarmed by the Left's unexpected rise in the polls, Germany's mainstream politicians hit back at Lafontaine and Gysi as "left populists" and "demagogues" and accused the party of flirting with neo-Nazi voters. A gaffe by Lafontaine, who described "foreign workers" as a threat in one speech early in the campaign, provided ammunition for charges that the Left was attempting to exploit German xenophobia.

Although Germany's once-powerful trade unions distanced themselves from The Left in the 2005 federal election, some union leaders expressed interest in cooperating with the party after the election. A number of regional trade union leaders and mid-level functionaries were active supporters.

2005 federal election outcome

At the 2005 federal election, the Left Party became the fourth-largest party in the Bundestag, with 54 Members of Parliament (MPs) (full list), ahead of the Greens (51) but behind the Free Democratic Party (61). Three Left Party MPs were directly elected on a constituency basis: Gregor Gysi, Gesine Lötzsch and Petra Pau, all in Eastern Berlin constituencies. In addition, 51 Left Party MPs were elected through the party list element of Germany's Additional Member System of proportional representation. These include Lothar Bisky, Katja Kipping, Oskar Lafontaine, and Paul Schäfer. Besides Lafontaine, a number of other prominent SPD defectors won election to the Bundestag on the Left Party list, including a prominent leader of Germany's Turkish minority, Hakkı Keskin, German Federal Constitutional Court justice Wolfgang Neskovic, and the former SPD leader in Baden-Württemberg, Ulrich Maurer.

When the votes were counted, the party doubled its federal vote from 1.9 million (PDS result in 2002) to more than 4 million—including an electoral breakthrough in industrial Saarland where, for the first time in a western state, it surpassed the Greens and FDP due, in large part to Lafontaine's popularity and Saarland roots. It is now the second strongest party in three states, all of them in the former GDR, (Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia) and the third strongest in four others, all but Saarland in the former GDR, (Saarland, Berlin, Saxony, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern). It was the only party to win over protest voters broadly across Germany's political spectrum: nearly one million Social Democratic voters defected to the Left while the Christian Democrats and Greens together lost half a million votes to the resurgent party.

Exit polls showed the Left had a unique appeal to non-voters: 390,000 Germans who refused to support any party in 2002 returned to the ballot box to vote for the Left Party. The Left's image as the last line of defense for Germany's traditional "social state" (Sozialstaat) proved to be a magnet for voters in western as well as eastern Germany.

All other established parties had ruled out the possibility of a coalition with the Left Party prior to the election (in other words, a cordon sanitaire), and refused to reconsider in the light of the closeness of the election result, which prevented either of the usual ideologically-coherent coalitions from attaining a majority. The possibility of a minority SPD–Green government tolerated by the Left Party was the closest the Left Party came to potential participation in government at this election.

2006 state election results

The Left Party suffered serious losses in the 2006 elections for the city-state government of Berlin, losing nearly half of its vote and falling to 13%—slightly ahead of the Greens. Berlin's popular Social Democratic mayor, Klaus Wowereit, nevertheless decided to retain the weakened party as his coalition partner.

In Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, the Left Party suffered no serious losses and remains the third-strongest party in the state. However, it was dropped as a coalition partner by the Social Democratic premier, Harold Ringstorff, and now heads the opposition in the state assembly.

Despite its losses in Berlin, support for the Left Party/PDS and its WASG ally remains stable at about eight to ten percent of the vote. Cooperation between the two parties on a national level and in their single Bundestag delegation has been largely free of tensions. Though a minority of WASG members opposed the merger of the two parties scheduled for June 2007, the new party – The Left – was on Germany's political stage before the federal elections.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In state and local government

The PDS had experience as a junior coalition partner in two federal states—Berlin and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania—where it co-governed until 2006 with the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Political responsibility has burnished the Left's reputation as a pragmatic, rather than ideological party. It remained strong in local government in eastern Germany, with more than 6,500 town councillors and 64 elected mayors.[when?] The party continued to win eastern voters by emphasizing political competence and refused to be labelled as merely a "protest party", although it certainly attracted millions of protest voters in the federal election,[which?] profiting from growing dissatisfaction with high unemployment and cutbacks in public health insurance, unemployment benefits, and labour rights.

Controversies

Stasi connections

After German reunification, leading members of the PDS were frequently suspected of having connections to East Germany's secret police, the Stasi (State Security Service). Shortly after the 2005 federal election, Marianne Birthler, the official in charge of the Stasi archives, accused the Left Party of harboring at least seven former Stasi informants in its newly elected parliamentary group.[26] At about the same time, the media revealed that Lutz Heilmann, a Left Party Bundestag deputy from the state of Schleswig-Holstein, had worked for several years for the Stasi.[27] While the first accusation proved to be false, Heilmann's connection with the Stasi remained controversial. Though Heilmann had served as a bodyguard, not as an informant or secret police officer, he violated a Left Party regulation obliging candidates to reveal Stasi involvement. Nevertheless, the Left Party membership in Schleswig-Holstein narrowly passed a vote of confidence in Heilmann, and he continued to serve in the Bundestag.

Charges of a Stasi past were also a factor in the Bundestag's decision to reject Lothar Bisky as the Left Party's candidate for the post of parliamentary vice president. Though Bisky's candidacy was supported by the Greens and by some Christian Democratic and Social Democratic leaders, including Chancellor Angela Merkel, after two failed votes the party withdrew his nomination. Five months later, the Left Party's Petra Pau was elected vice president.

In the Saxony, the chairman of the Left Party group, Peter Porsch, faced losing his mandate in the Saxon parliament because of his alleged Stasi past. In May 2006, all parties represented in the parliament, except the Left Party, voted to initiate proceedings against Porsch.[بحاجة لمصدر] However, in November, the state's constitutional court dismissed the complaint against Porsch on technical grounds.

SED assets

The SED had sequestered money overseas in secret accounts, including some which turned up in Liechtenstein in 2008. This was returned to the German government, as the PDS had rejected claims to overseas SED assets in 1990.[28] The vast majority of domestic SED assets were transferred to the GDR government before unification. Legal issues over back taxes possibly owed by the PDS on former SED assets were eventually settled in 1995, when an agreement between the PDS and the Independent Commission on Property of Political Parties and Mass Organizations of the GDR was confirmed by the Berlin Administrative Court.[29]

Election results

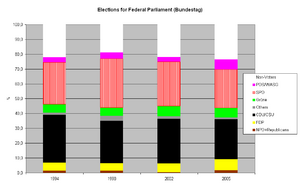

Federal Parliament (Bundestag)

| Election year | # of constituency votes |

# of party list votes |

% of party list vote |

# of overall seats won | +/− | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1,049,245 | 1,129,578 | 2.4 (#5) | 17 / 614

|

▲ 17 | |

| 1994 | 1,920,420 | 2,066,176 | 4.4 (#5) | 30 / 622

|

▲ 13 | |

| 1998 | 2,416,781 | 2,515,454 | 5.1 (#5) | 36 / 631

|

▲ 6 | |

| 2002 | 2,079,203 | 1,916,702 | 4.0 (#5) | 2 / 603

|

||

| 2005[a] | 3,764,168 | 4,118,194 | 8.7 (#4) | 54 / 614 [b]

|

▲ 52 |

Volkskammer (East Germany)

| Election year | # of votes | % of votes | # of seats won | +/− | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1,892,381 | 16.4 (#3) | 66 / 400

|

European Parliament

| Election year | # of party list votes |

% of party list vote |

# of overall seats won | +/− | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 1,670,316 | 4.7 (#4) | 0 / 99

|

– | |

| 1999 | 1,567,745 | 5.8 (#4) | 6 / 99

|

▲ 6 | |

| 2004 | 1,579,109 | 6.1 (#4) | 7 / 99

|

▲ 1 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

- اليسار

- سياسة ألمانيا

- List of political parties in Germany

- Bundestag (Federal Assembly of Germany)

المراجع

- ^ König, Thomas; Finke, Daniel (March 2015). "Legislative Governance in Times of International Terrorism". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 59 (2): 262–282. doi:10.1177/0022002713503298.

- ^ Oswald, Franz (12 November 2007). "The party of democratic socialism: Ex-communists entrenched as East German regional protest party". Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics. 12 (2): 173-195. doi:10.1080/13523279608415308.

- ^ Yoder, Jennifer (1999). From East Germans to Germans?: The New Postcommunist Elites. Duke University Press. p. 188. ISBN 9780822323723.

- ^ [1][2][3]

- ^ Klingelhöfer, Tristan; Richter, Simon; Loew, Nicole (2024). "Changing affective alignments between parties and voters". West European Politics: 1–28. doi:10.1080/01402382.2023.2295735.

- ^ Engel, Ulf (2002). Germany's Africa Policy Revisited: Interests, Images and Incrementalism. LIT Verlag Munster. p. 22. ISBN 9783825859855.

- ^ [5][6]

- ^ Saalfeld, Thomas (2002). "The German Party System: Continuity and Change". German Politics. 11 (3): 99–130. doi:10.1080/714001303.

- ^ Dunphy, Richard (2004). Contesting Capitalism?: Left Parties and European Integration. Manchester University Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780719068041.

- ^ [8][9]

- ^ Peter Barker (ed.) The Party of Democratic Socialism in Germany: Modern Post-communism Or Nostalgic Populism?, 1998

- ^ أ ب Eric D. Weitz, Creating German Communism, 1890-1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997

- ^ Eric Canepa, Germany's Party of Democratic Socialism, Socialist Register, Vol. 30, 1994

- ^ أ ب Dominic Heilig, Mapping the European Left: Socialist Parties in the EU Archived 2019-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, April 2016

- ^ David F. Patton. Out of the East: From PDS to Left Party in Unified Germany (State University of New York Press; 2011)

- ^ أ ب Hough, Dan; Koss, Michael; Olsen, Jonathan (2007-09-12). The Left Party in Contemporary German Politics (in الإنجليزية). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 14–17. ISBN 978-0-230-01907-2.

- ^ Mary Elise Sarotte, Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall, New York: Basic Books, 2014

- ^ Meisner, Matthias (8 September 2013). "Von der SED zur Linkspartei: Auferstanden aus Ruinen". Zeit Online (in الألمانية). Hamburg: Zeit Online GmbH. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Helmut Müller-Enbergs. "Schumann, Michael *24.12.1946, † 2.12.2000 PDS-Politiker" (in الألمانية). Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur: Biographische Datenbanken. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ "Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System!"

- ^ David Priestand, Red Flag: A History of Communism, New York: Grove Press, 2009

- ^ Tuohy, William (1989-12-04). "Entire East German Leadership Resigns". Los Angeles Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-10-31.

- ^ mdr.de. "Honecker, Erich | MDR.DE". www.mdr.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 2021-10-31.

- ^ Mary Elise Sarotte, 1989: The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe (2nd ed.), Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014

- ^ "German election: Could there soon be a left-wing government?". Deutsche Welle. 24 September 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Secret Police in Germany's Parliament?". Deutsche Welle. 23 September 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Belasteter Abgeordneter: Linkspartei-Mann arbeitete für die Stasi". Der Spiegel (in الألمانية). 8 October 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Verschwundene SED-Millionen: Magazin meldet Spur in Liechtenstein". Der Spiegel. 19 February 2008.

- ^ Franz Oswald 2002, The Party That Came Out Of The Cold War, pp. 69–71

للاستزادة

- Barker, Peter, ed. (1998). The Party of Democratic Socialism in Germany: Modern Post-Communism or Nostalgic Populism. Rodopi.

- Hough, Dan (2001). The Fall and Rise of the PDS in Eastern Germany (1st ed.). The University of Birmingham Press. ISBN 1-902459-14-8

- Oswald, Franz (2002). The Party That Came Out of the Cold War : The Party of Democratic Socialism in United Germany. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-97731-5

- Thompson, Peter (2005) The Crisis of the German Left. The PDS, Stalinism and the Global Economy Berghahn Books, New York and Oxford. ISBN 1-57181-543-0

وصلات خارجية

- Left Party website in German

- Der Spiegel on the Founding of the Left Party (English)

- Left Party Bundestag site with profiles of deputies

- Ingo Schmidt, "The Left Opposition in Germany. Why Is the Left So Weak When So Many Are Looking for Political Alternatives?", in Monthly Review, May 2007

- Ingar Solty "The Historic Significance of the New German Left Party"

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Vague or ambiguous time from September 2013

- المقالات needing additional references from April 2023

- كل المقالات needing additional references

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- المقالات needing additional references from November 2012

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from September 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2021

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Defunct socialist parties in Germany

- Organizations of the Revolutions of 1989

- أحزاب تأسست في 1990

- أحزاب انحلت في 2007

- Peaceful Revolution

- تأسيسات 1990 في ألمانيا

- انحلالات 2007 في ألمانيا

- اليسار (ألمانيا)