جورج سميث (عالم آشوريات)

George Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| وُلِدَ | 26 مارس 1840 |

| توفي | 19 أغسطس 1876 (aged 36) |

| الجنسية | بريطاني |

| اللقب | اكتشف وترجم ملحمة گلگامش |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | علم الآشوريات |

| الهيئات | المتحف البريطاني |

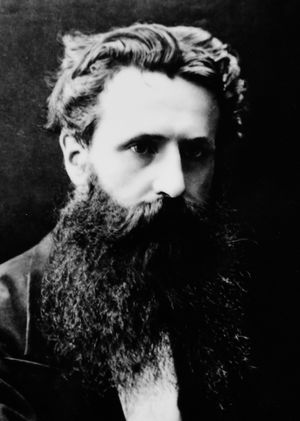

جورج سميث (George Smith ؛ عاش 26 مارس 1840 - 19 أغسطس 1876) كان عالم آشوريات إنگليزي رائد الذي كان أول من اكتشف وترجم ملحمة گلگامش، أحد أقدم الأعمال الأدبية المكتوبة المعروفة في العالم.[1]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

النشأة وبداية العمل

As the son of a working-class family in Victorian England, Smith was limited in his ability to acquire a formal education.[2] At age fourteen, he was apprenticed to the London-based publishing house of Bradbury and Evans to learn banknote engraving, at which he excelled. From his youth, he was fascinated with Assyrian culture and history. In his spare time, he read everything that was available to him on the subject. His interest was so keen that while working at the printing firm, he spent his lunch hours at the British Museum, studying publications on the cuneiform tablets that had been unearthed near Mosul in present-day Iraq by Austen Henry Layard, Henry Rawlinson, and their Iraqi assistant Hormuzd Rassam, during the archaeological expeditions of 1840–1855. In 1863 Smith married Mary Clifton (1835 – 1883), and they had six children.

المتحف البريطاني

Smith's natural talent for cuneiform studies was first noticed by Samuel Birch, Egyptologist and Director of the Department of Antiquities, who brought the young man to the attention of the renowned Assyriologist Sir Henry Rawlinson. As early as 1861, he was working evenings sorting and cleaning the mass of friable fragments of clay cylinders and tablets in the Museum's storage rooms.[3] In 1866 Smith made his first important discovery, the date of the payment of the tribute by Jehu, king of Israel, to Shalmaneser III. Sir Henry suggested to the Trustees of the Museum that Smith should join him in the preparation of the third and fourth volumes of The Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia.[4] Following the death of William H. Coxe in 1869 and with letters of reference from Rawlinson, Layard, William Henry Fox Talbot, and Edwin Norris, Smith was appointed Senior Assistant in the Assyriology Department early in 1870.

اكتشاف النقوش

Smith's earliest successes were the discoveries of two unique inscriptions early in 1867. The first, a total eclipse of the sun in the month of Sivan inscribed on Tablet K51, he linked to the spectacular eclipse that occurred on 15 June 763 BC, a description of which had been published 80 years earlier by French historian François Clément (1714 – 1793) in L'art de vérifier les dates des faits historiques.[5] This discovery is the cornerstone of ancient Near Eastern chronology. The other was the date of an invasion of Babylonia by the Elamites in 2280 BC.

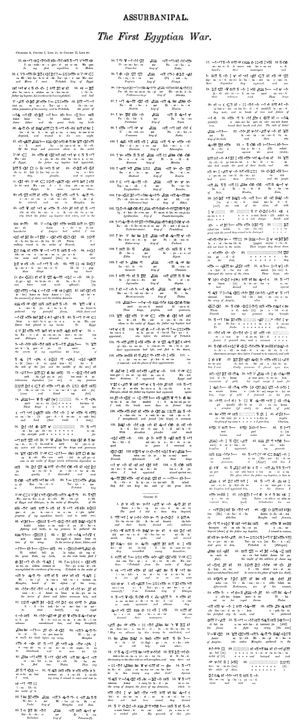

In 1871, Smith published Annals of Assur-bani-pal, transliterated and translated, and communicated to the newly founded Society of Biblical Archaeology a paper on "The Early History of Babylonia", and an account of his decipherment of the Cypriote inscriptions.

ملحمة گلگامش والحملة الأثرية إلى نينوى

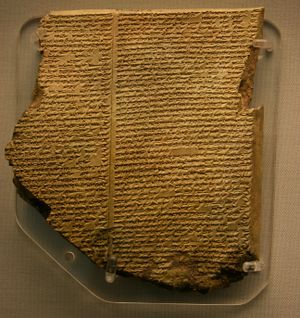

In 1872, Smith achieved worldwide fame by his translation of the Chaldaean account of the Great Flood, which he read before the Society of Biblical Archaeology on 3 December and whose audience included the Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.[7]

This work is better known today as the eleventh tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest known works of literature. The following January, Edwin Arnold, the editor of The Daily Telegraph, arranged for Smith to go to Nineveh at the expense of that newspaper and carry out excavations with a view to finding the missing fragments of the Flood story. This journey resulted not only in the discovery of some missing tablets, but also of fragments that recorded the succession and duration of the Babylonian dynasties.

In November 1873 Smith again left England for Nineveh for a second expedition, this time at the expense of the Museum, and continued his excavations at the tell of Kouyunjik (Nineveh). An account of his work is given in Assyrian Discoveries, published early in 1875. The rest of the year was spent in fixing together and translating the fragments relating to the creation, the results of which were published in The Chaldaean Account of Genesis (1880, co-written with Archibald Sayce).

الحملة الأخيرة ووفاته

In March 1876, the trustees of the British Museum sent Smith once more to excavate the rest of the Library of Ashurbanipal. At Ikisji, a small village about sixty miles northeast of Aleppo, he fell ill with dysentery. He died in Aleppo on 19 August. He left a wife and several children to whom an annuity of 150 pounds was granted by the Queen.

ببليوگرافيا

Smith wrote about eight important works,[8] including linguistic studies, historical works, and translations of major Mesopotamian literary texts. They include:

- George Smith (1871). History of Assurbanipal, translated from the cuneiform inscriptions.

- George Smith (1875). Assyrian Discoveries: An Account of Explorations and Discoveries on the Site of Nineveh, During 1873 to 1874

- George Smith (1876). The Chaldean Account of Genesis

- George Smith (1878), Sayce, A.H, ed., History of Sennacherib: Translated from the Cuneiform Inscriptions, London: Williams & Norgate, https://archive.org/details/historysennache00smitgoog

- George Smith (18 – ). The History of Babylonia. Edited by Archibald Henry Sayce.

نسخ أونلاين

- History of Assurbanipal, translated from the cuneiform inscriptions. London: Williams and Norgate, 1871. From Google Books.

- Assyrian Discoveries. New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1876. From Google Books.

- The Chaldean Account of Genesis. New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1876. From WisdomLib.

- History of Sennacherib. London: Williams and Norgate, 1878. From Internet Archive.

- The History of Babylonia. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; New York: E. & J. B. Young. From Internet Archive.

المراجع

- David Damrosch. The Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh (2007). ISBN 978-0-8050-8029-2. Ch 1–2 (80 pages) of Smith's life, includes new-found evidence about Smith's death.

- C. W. Ceram [Kurt W. Marek] (1967), Gods, Graves and Scholars: The Story of Archeology, trans. E. B. Garside and Sophie Wilkins, 2nd ed. New York: Knopf, 1967. See chapter 22.

- Robert S. Strother (1971). "The great good luck of Mister Smith", in Saudi Aramco World, Volume 22, Number 1, January/February 1971. Last accessed March 2007.

- "George Smith" (1876), by Archibald Henry Sayce, in Littell's Living Age, Volume 131, Issue 1687.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 25 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 261.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - David Damrosch (2007). "Epic Hero", in Smithsonian, Volume 38, Number 2, May 2007.

الهامش

- ^ Barry Hoberman, " B[iblical] Archaeologist] Portrait: George Smith (1840–1876) Pioneer Assyriologist", The Biblical Archaeologist 46.1 (Winter 1983), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Damrosch, pp.12–15

- ^ George Rawlinson. A Memoir of Major-General Henry Creswicke Rawlinson. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1882; A facsimile of the first edition. Elibron Classic series, 2005; pp. 240–1.

- ^ The Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia published in London, Volume III in 1871 and Volume IV in 1875.

- ^ Henry C.Rawlinson, "The Assyrian Canon Verified by the Record of a Solar Eclipse, B.C. 763." The Athenaeum No. 2064, London: 18 May 1867, pp. 660–1.

- ^ Smith, George (1871). History of Assurbanipall, Translated from the Cuneiform Inscriptions by George Smith (in English). Williams and Norgate. pp. 15ff.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Secrets of Noah's Ark - Transcript". Nova. PBS. 7 أكتوبر 2015. Retrieved 27 مايو 2019.

- ^ Damrosch, p.77

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

وصلات خارجية

Media related to George Smith (assyriologist) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Smith (assyriologist) at Wikimedia Commons- Smith, The Chaldean account of Genesis Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection.

- The Chaldean account of Genesis HTML with images

- George Smith | British Assyriologist

- EngvarB from August 2014

- Use dmy dates from August 2014

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- مواليد 1840

- وفيات 1876

- أشخاص من تشلسي، لندن

- علماء آثار إنگليز

- علماء آشوريات إنگليز

- وفيات بالزحار

- كتاب ڤكتوريون

- 19th-century English writers

- علماء آثار القرن 19

- مغتربون بريطانيون في الدولة العثمانية