پرث

}}}}

| پرث Western Australia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

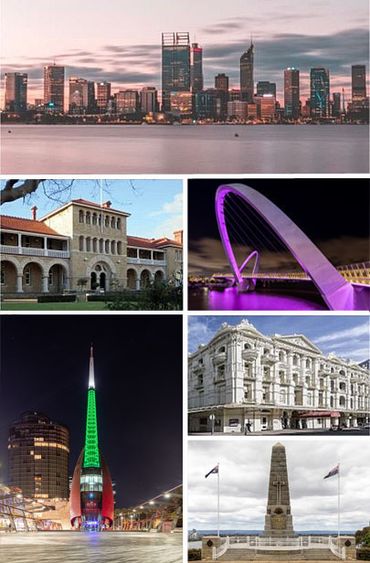

From top, left to right: Perth's skyline viewed from South Perth, Perth Mint, Elizabeth Quay bridge, Swan Bell Tower, His Majesty's Theatre, Kings Park State War Memorial | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 31°57′8″S 115°51′32″E / 31.95222°S 115.85889°E | ||||||||

| Population | 2٬059٬484 (2018)[1] (4th) | ||||||||

| • Density | 320٫8969/km2 (831٫119/sq mi) | ||||||||

| Established | 1829 | ||||||||

| Area | 6٬417٫9 km2 (2٬478�0 sq mi)(GCCSA)[2] | ||||||||

| Time zone | AWST (UTC+08:00) | ||||||||

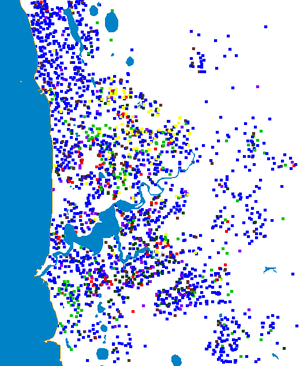

| Location | |||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Perth (and 41 others)[7] | ||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Perth (and 10 others) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

پرث (بالإنجليزية: Perth ؛ نيونگا: Boorloo) هي عاصمة ولاية أستراليا الغربية، والمدينة الأكثر اكتظاظاً بالسكان فيها.[8] بلغ عدد سكانها 2.1 مليون نسمة في يونيو عام 2020 مما يجعلها رابع أكبر مدن أستراليا من ناحية عدد السكان. مساحتها 5386 كم2. Perth is part of the South West Land Division of Western Australia, with most of the metropolitan area on the Swan Coastal Plain between the Indian Ocean and the Darling Scarp. The city has expanded outward from the original British settlements on the Swan River, upon which the city's central business district and port of Fremantle are situated. Perth is located on the traditional lands of the Whadjuk Noongar people, where Aboriginal Australians have lived for at least 45,000 years.[9]

Captain James Stirling founded Perth in 1829 as the administrative centre of the Swan River Colony. It was named after the city of Perth in Scotland, due to the influence of Stirling's patron Sir George Murray, who had connections with the area. It gained city status in 1856, although the Perth City Council currently governs only a small area around the central business district. The city's population increased substantially as a result of the Western Australian gold rushes in the late 19th century. It has grown steadily since World War II due to a high net migration rate. Post-war immigrants were predominantly from the British Isles and Southern Europe, while more recent arrivals see a growing population of Asian descent.[10] Several mining booms in other parts of Western Australia in the late 20th and early 21st centuries saw Perth become the regional headquarters for large mining operations.

Perth contains a number of important public buildings as well as cultural and heritage sites. Notable government buildings include Parliament House, Government House, the Supreme Court Buildings and the Perth Mint. The city is served by Fremantle Harbour and Perth Airport. It was a naval base for the Allies during World War II and today, the Royal Australian Navy's Fleet Base West is located on Garden Island. All five of Western Australia's universities are based in Perth.

The city has been ranked as one of the world's most liveable cities, and was classified by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network in 2020 as a Beta global city.[11]

اعتبارا من 2021[تحديث] Perth is divided into 30 local government areas and consists of more than 350 suburbs. The metropolitan boundaries stretch 123 كيلومتر (76 mi) from Two Rocks in the north to Singleton in the south,[12] and 62 كيلومتر (39 mi) east inland to The Lakes. Outside of the central business district, important urban centres within the metropolitan area include Armadale, Fremantle, Joondalup, Midland, and Rockingham. Most of those were originally established as separate settlements and retained a distinct identity after being subsumed into the wider metropolitan area. Mandurah, Western Australia's second-largest city, forms a conurbation with Perth along the coast, though for most purposes it is still considered a separate city.

اسم المكان

The name Perth was selected in recognition of Perth, Scotland[13][14][صفحة مطلوبة] as the birthplace of the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, and Member for Perthshire in the British House of Commons, Sir George Murray. It was included in Stirling's proclamation of the colony, read in Fremantle on 18 June 1829, which ended "Given under my hand and Seal at Perth this 18th Day of June 1829. James Stirling Lieutenant Governor".[15] The only contemporary information on the source of the name comes from Charles Fremantle's diary entry for 12 August 1829, which records that they "named the town Perth according to the wishes of Sir George Murray".[16][17][18]

There is no equivalent Noongar terminology for the Perth metropolitan area;[بحاجة لمصدر] it is sited primarily on Whadjuk country, which extends approximately[note 1] north to Two Rocks, south to Mandurah, and east as far as York.[19][20][21] Boorloo (also transcribed as Boorlo or Burrell) referred to Point Fraser[22][23] in East Perth, and means "big swamp",[23] which describes the whole chain of lakes where the CBD and Northbridge are sited.[24] However Boorloo is also used to denote the central business district,[25][26] the local government area,[27] or the capital city in general.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that the Noongar people have inhabited the Perth area for at least 45,000 years.[9] Noongar country encompasses the southwest corner of Western Australia. The wetlands on the Swan Coastal Plain were particularly important to them, both spiritually (featuring in local mythology) and as a source of food.[36]

The present-day location of the CBD forms part of the traditional territory of the Mooro, a Noongar clan, who at the time of British settlement had Yellagonga as their leader. The Mooro was one of several Noongar clans based around the Swan River, known collectively as the Whadjuk. The Whadjuk themselves were one of a larger group of fourteen tribes that formed the south-west socio-linguistic block known as the Noongar (meaning "the people" in their language), also sometimes called the Bibbulmun.[37]

On 19 September 2006, the Federal Court of Australia brought down a judgment finding that Noongar native title continued to exist over the Perth metropolitan area in the case of Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243.[38] An appeal was subsequently lodged and in 2008 the Full Court of the Federal Court upheld parts of the appeal by the Western Australian and Commonwealth governments.[39] Following this appeal, the WA Government and the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council negotiated the South West Native Title Settlement, including the Whadjuk Indigenous Land Use Agreement over the Perth region, which was finalised by the Federal Court on 1 December 2021.[40] As part of reaching this agreement, the Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Act was passed in 2016, recognising the Noongar people as the traditional owners of the south west region of Western Australia.[41]

Early European sightings and exploration

The Dutch Captain Willem de Vlamingh and his crew made the first documented sighting of the present-day Perth region by Europeans on 10 January 1697. They initially explored the area on foot, reaching what is now central Perth,[42] having travelled up the Swan River.[43] They named the river Swarte Swaene-Revier after the black swans of the area.[43] Other Europeans made subsequent sightings and undertook further voyages of exploration of the area between this date and 1829, but as in the case of the observations made by Vlamingh, they adjudged the area inhospitable and unsuitable for the agriculture that would be needed to sustain a European-style settlement.[44]

مستعمرة نهر البجع

Although the Colony of New South Wales established a convict-supported settlement at King George's Sound (later Albany) on the south coast of Western Australia in 1826 in response to rumours that France intended to annex the area, Perth became the first "full-scale" settlement by Europeans in the western third of the continent of Australia in 1829. The British colony would be officially designated "Western Australia" in 1832 but was known informally for many years as the "Swan River Colony" after the area's major watercourse.[45]

On 4 June 1829, newly arriving British colonists had their first view of the mainland, and Western Australia has subsequently celebrated a public holiday on the first Monday in June each year. Captain James Stirling, aboard Parmelia, noted that the site was "as beautiful as anything of this kind I had ever witnessed". On 12 August that year, Helen Dance, wife of the captain of the second ship, Sulphur, cut down a tree to mark the founding of the town. Beginning in 1831, hostile encounters between the British settlers and the Noongar people – both large-scale land users, with conflicting land-value systems – increased considerably as the colony grew. The hostile encounters between the two groups of people resulted in multiple events, including the murder of settlers (such as Thomas Peel's servant Hugh Nesbitt[46]), the execution of the Whadjuk elder Midgegooroo, the death of his son Yagan in 1833, and the Pinjarra massacre in 1834.

The relations between the Noongar people and the Europeans became strained due to these events. The increasing use of the land for agricultural purposes restricted the hunter-gatherer practices of the native Whadjuk Noongar. They were forced to camp around prescribed areas, including the swamps and lakes north of the European settlement area. Third Swamp, known to them as Boodjamooling, continued to be a main campsite for the remaining Noongar people in the Perth region and was also used by travellers, itinerants, and homeless people. By the gold-rush days of the 1890s, they were joined by miners who were en route to the goldfields.[47]

عصر المدانين والهروع إلى الذهب

In 1850, at a time when penal transportation to Australia's eastern colonies had ceased, Western Australia was opened to convicts at the request of farming and business people due to a shortage of labour.[48] Over the next eighteen years, 9,721 convicts arrived in Western Australia aboard 43 ships.

Queen Victoria announced the city status of Perth in 1856.[49] Despite this proclamation, Perth was still a quiet town, described in 1870 by a Melbourne journalist as:

"...a quiet little town of some 3000 inhabitants spread out in straggling allotments down to the water's edge, intermingled with gardens and shrubberies and half rural in its aspect ... The main streets are macadamised, but the outlying ones and most of the footpaths retain their native state from the loose sand — the all pervading element of Western Australia — productive of intense glare or much dust in the summer and dissolving into slush during the rainy season."[50]

With the discovery of gold at Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie in the late 19th century, Western Australia experienced a mining boom,[51] and Perth's population grew from approximately 8,500 in 1881 to 61,000 in 1901.[52]

الاتحاد وما بعده

After a referendum in 1900,[53] Western Australia joined the Federation of Australia in 1901.[49] It was the last of the Australian colonies to agree to join the Federation, and it did so only after the other colonies had offered several concessions, including the construction of a transcontinental railway line from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie to link Perth with the eastern states.[54]

In 1927, Indigenous people were prohibited from entering large swathes of Perth under penalty of imprisonment, a ban that lasted until 1954.[55]

In 1933, two-thirds of Western Australians voted in a referendum to secede from the Australian Federation. However, the state general election held at the same time as the referendum had voted out the incumbent "pro-independence" government, replacing it with a government that did not support the independence movement. Respecting the result of the referendum, the new government nonetheless petitioned the Imperial Parliament at Westminster. The House of Commons established a select committee to consider the issue but after 18 months of negotiations and lobbying, finally refused to consider the matter, declaring that it could not legally grant secession.[53][56]

Perth entered the post-war period with a population of approximately 280,000 and an economy that had not experienced sustained growth since the 1920s. Successive state governments, beginning with the Willcock Labor Government (1936-1945), determined to change this. Planning for post-war economic development was initially driven by Russell Dumas, who as Director of Public Works (1941-1953) drew up plans for Western Australia's major post-war public-works projects, including the raising of the Mundaring and Wellington Dams, the development of the new Perth Airport, and the development of a new industrial zone centred on Kwinana. The advent of the McLarty Liberal Government (1947-1953) saw the emergence of something of a consensus on the need for continuing economic development. Economic growth was fuelled by large-scale public works, the post-war immigration program, and the success that various state governments had in attracting substantial foreign investment into the state, beginning with the construction of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Refinery at Kwinana in 1951–52.[57]

The result of this economic activity was the rapid growth of the population of Perth and a marked change in its urban design. Commencing in the 1950s, Perth began to expand along an extensive highway network laid out in the Stephenson-Hepburn Report, which noted that Perth was beginning to resemble a pattern of development less in line with the British experience and more in line with North America.[58] This was encouraged by the opening of the Narrows Bridge and the gradual closure of the Perth-Fremantle Tramways. The mining-pastoral boom of the 1960s only accelerated the pace of urban growth in Perth.

In 1962, Perth received global media attention when city residents lit their house lights and streetlights as American astronaut John Glenn passed overhead while orbiting the Earth on Friendship 7. This led to its being nicknamed the "City of Light".[59][60][61] The city repeated the act as Glenn passed overhead on the Space Shuttle in 1998.[62][63]

Perth's development and relative prosperity, especially since the mid-1960s,[64] has resulted from its role as the main service centre for the state's resource industries, which extract gold, iron ore, nickel, alumina, diamonds, mineral sands, coal, oil, and natural gas.[65] Whilst most mineral and petroleum production takes place elsewhere in the state, the non-base services provide most of the employment and income to the people of Perth.[66]

الجغرافيا

وسط البلد التجاري

The central business district of Perth is bounded by the نهر البجع to the south and east, with Kings Park on the western end and the railway reserve as the northern border.[بحاجة لمصدر] A state and federally funded project named Perth City Link sank a section of the railway line to allow easy pedestrian access between Northbridge and the CBD. The Perth Arena is an entertainment and sporting arena in the city link area that has received several architectural awards from institutions such as the Design Institute of Australia, the Australian Institute of Architects, and Colorbond.[67] St Georges Terrace is the area's prominent street, with a large amount of office space in the CBD. Hay Street and Murray Street have most of the retail and entertainment facilities. The city's tallest building is Central Park, the twelfth tallest building in Australia.[68] The CBD until 2012 was the centre of a mining-induced boom, with several commercial and residential projects being built, including Brookfield Place, a 244 m (801 ft) office building for Anglo-Australian mining company BHP.[69]

المناخ

| بيانات المناخ لـ پرث، أستراليا الغربية | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 45.8 (114.4) |

46.2 (115.2) |

42.4 (108.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.3 (93.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.3 (99.1) |

40.3 (104.5) |

44.2 (111.6) |

46.2 (115.2) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 31.3 (88.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.1 (84.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 24.8 (76.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 18.2 (64.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | 8.9 (48.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 15.4 (0.61) |

8.8 (0.35) |

20.5 (0.81) |

36.5 (1.44) |

90.2 (3.55) |

126.7 (4.99) |

144.7 (5.70) |

122.4 (4.82) |

88.0 (3.46) |

38.6 (1.52) |

23.7 (0.93) |

9.9 (0.39) |

730.5 (28.76) |

| Average precipitation days | 2.4 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 6.7 | 11.1 | 15.2 | 16.9 | 15.7 | 15.3 | 8.7 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 108.4 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية بعد الظهر (%) (at 1500) | 39 | 38 | 39 | 46 | 50 | 56 | 57 | 54 | 53 | 46 | 44 | 41 | 47 |

| المتوسط اليومي ساعات سطوع الشمس | 11.5 | 11.0 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 8.8 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[70][71][72] Temperatures: 1993–2015; Extremes: 1897–2015; Rain data: 1876–2012 | |||||||||||||

| بيانات المناخ لـ كالاموندا | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 30.4 (86.7) |

30.3 (86.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 16.2 (61.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 11.9 (0.47) |

17.6 (0.69) |

22.7 (0.89) |

55.7 (2.19) |

144.3 (5.68) |

216.2 (8.51) |

213.8 (8.42) |

165.9 (6.53) |

102.1 (4.02) |

70.5 (2.78) |

28.6 (1.13) |

19.6 (0.77) |

1٬065٫9 (41.96) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[73] | |||||||||||||

| بيانات المناخ لـ مطار جانداكوت | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 45.7 (114.3) |

46.6 (115.9) |

43.0 (109.4) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.4 (92.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

40.0 (104.0) |

44.0 (111.2) |

46.6 (115.9) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 31.4 (88.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 16.8 (62.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

6.77 (44.19) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 13.8 (0.54) |

16.3 (0.64) |

16.1 (0.63) |

42.3 (1.67) |

107.3 (4.22) |

156.6 (6.17) |

173.7 (6.84) |

126.0 (4.96) |

88.0 (3.46) |

46.0 (1.81) |

29.1 (1.15) |

10.5 (0.41) |

821.0 (32.32) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[74] | |||||||||||||

| بيانات المناخ لپرث | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| متوسط درجة حرارة البحر °س (°ف) | 21.0 (69.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 |

| متوسط مؤشر فوق البنفسجية | 11+ | 11 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11+ | 7.2 |

| Source #1: METOC (sea temperature),[75] ARPANSA (UV index) [76] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Bureau of Meteorology (daylight hours) [77] | |||||||||||||

السكان

| Historical populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Perth is Australia's fourth-most populous city, having overtaken Adelaide's population in 1984.[81] In June 2015 there were approximately 2.04 million residents in the metropolitan area.[82]

الجماعات العرقية

| Overseas-born populations[83] | |

|---|---|

| بلد الميلاد | التعداد (2006) |

| 168,483 | |

| 33,751 | |

| 28,939 | |

| 18,701 | |

| 18,683 | |

| 14,007 | |

| 11,199 | |

| 10,081 | |

| 7,706 | |

| 7,681 | |

| 7,617 | |

| 7,570 | |

| 7,392 | |

| 5,524 | |

الاقتصاد

By virtue of its population and role as the administrative centre for business and government, Perth dominates the Western Australian economy, despite the major mining, petroleum, and agricultural export industries being located elsewhere in the state.[84] Perth's function as the state's capital city, its economic base and population size have also created development opportunities for many other businesses oriented to local or more diversified markets. Perth's economy has been changing in favour of the service industries since the 1950s. Although one of the major sets of services it provides is related to the resources industry and, to a lesser extent, agriculture, most people in Perth are not connected to either; they have jobs that provide services to other people in Perth.[85]

As a result of Perth's relative geographical isolation, it has never had the necessary conditions to develop significant manufacturing industries other than those serving the immediate needs of its residents, mining, agriculture and some specialised areas, such as, in recent times, niche shipbuilding and maintenance. It was simply cheaper to import all the needed manufactured goods from either the eastern states or overseas.

Industrial employment influenced the economic geography of Perth. After WWII, Perth experienced suburban expansion aided by high levels of car ownership. Workforce decentralisation and transport improvements made it possible for the establishment of small-scale manufacturing in the suburbs. Many firms took advantage of relatively cheap land to build spacious, single-storey plants in suburban locations with plentiful parking, easy access and minimal traffic congestion. "The former close ties of manufacturing with near-central and/or rail-side locations were loosened."[84]

Industrial estates such as Kwinana, Welshpool and Kewdale were post-war additions contributing to the growth of manufacturing south of the river. The establishment of the Kwinana industrial area was supported by standardisation of the east–west rail gauge linking Perth with eastern Australia. Since the 1950s the area has been dominated by heavy industry, including an oil refinery, steel-rolling mill with a blast furnace, alumina refinery, power station, and a nickel refinery. Another development, also linked with rail standardisation, was in 1968 when the Kewdale Freight Terminal was developed adjacent to the Welshpool industrial area, replacing the former Perth railway yards.[84]

With significant population growth post-WWII,[86] employment growth occurred not in manufacturing but in retail and wholesale trade, business services, health, education, community and personal services, and in public administration. Increasingly it was these services sectors, concentrated around the Perth metropolitan area, that provided jobs.[84]

Perth has also become a hub of technology-focused startups since the early 2000s that provide a pool of highly skilled jobs to the Perth community. Companies such as Appbot, Agworld, Touchgram, and Healthengine all hail from Perth and have made headlines internationally. Programs like StartupWA and incubators such as Spacecubed and Vocus Upstart are all focused on creating a thriving startup culture in Perth and growing the next generation of Perth-based employers.[بحاجة لمصدر]

انظر أيضاً

- List of Perth suburbs

- Islands of Perth, Western Australia

- The Worst of Perth, a blog looking at the worst examples of architecture, design, culture and humanity in Perth

الهامش

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2017–18". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019. ERP at 30 June 2018.

- ^ "Greater Perth: Basic Community Profile" (xls). 2011 Census Community Profiles. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 March 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between PERTH and ADELAIDE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between PERTH and DARWIN CITY". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between PERTH and MELBOURNE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between PERTH and SYDNEY". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "2011 Electoral Boundaries". State of Western Australia – Office of the Electoral Distribution Commissioners. 2014. Archived from the original on 27 فبراير 2013. Retrieved 20 فبراير 2014.

- ^ Radcliffe, John C. (2019). "History of Water Sensitive Urban Design/Low Impact Development Adoption in Australia and Internationally". Approaches to Water Sensitive Urban Design. Elsevier. pp. 1–24. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-812843-5.00001-0. ISBN 9780128128435. S2CID 135280650.

Much of Perth, the capital city of Western Australia, is built on a sand plain so that stormwater infiltration to groundwater is the default stormwater management.

- ^ أ ب "Noongar History". Wa.gov.au. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Perth, the migrant city - McCrindle". mccrindle.com.au (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC – Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Holland, Steve (8 August 2015). "Why Perth could soon be the world's longest city". WAtoday. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Kimberly, W. B. (1897). . Melbourne: F. W. Niven & Co. p. 44.

- ^ Crowley, Francis K. (1960). Australia's Western Third. London: Macmillan & Co.

- ^

James Stirling: Lieutenant-Governor Stirling's Proclamation of the Colony 18 June 1829 on Wikisource

James Stirling: Lieutenant-Governor Stirling's Proclamation of the Colony 18 June 1829 on Wikisource

- ^ Fremantle, John (1928). Diary & Letters of Admiral Sir C. H. Fremantle, G.C.B. Relating the Founding of the Colony of Western Australia 1829. London: Hazell, Watson & Viey.

- ^ Uren, Malcolm J. L. (1948). Land Looking West. London: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Statham, Pamela (1981). "Swan River Colony". In Stannage, Tom (ed.). A New History of Western Australia. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press. ISBN 0-85564-181-9.

- ^ "Whadjuk Boodjar". Derbalnara.org.au. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "Map of Indigenous Australia". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Norman Tindale (1940). "Map showing the distribution of the Aboriginal tribes of Australia". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 8 May 2022 – via Trove.

- ^ Forster, Pat (2018). "Noongar place names: Swan-Canning Estuary and environs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ أ ب Forster, Pat (2020). "Noongar Placenames With Connections To Water" (PDF). Retrieved 27 May 2021.

The practice identified by Collard et. al. of having multiple names for the same place is evidenced with Boorlo, meaning big swamp and Boodjargabbeelup, meaning the place where water meets the land, both referring to Point Fraser.

- ^ Harben, Sandra (2019). "Whadjuk Oral History recordings". WA Museum Boola Bardip.

- ^ "Gnarla Boodja Mili Mili (Our Country on Paper)". Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries. 15 September 2019. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

the Perth CBD area, also known as Boorlo or Burrell in the Noongar language

- ^ Coates, Erin; James, Stuart; Devenish, Louise (1 January 2020), Alluvium, Edith Cowan University, Research Online, Perth, Western Australia, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/248568338, retrieved on 13 April 2022

- ^ "Minutes of the Ordinary Council Meeting". City of Perth. 6 July 2021. Attachment 12.1A – Yacker Danjoo Ngala Bidi (Working Together Our Way). Retrieved 24 April 2022.

The City of Perth (Boorloo)

- ^ "Tourism Australia adopts Aboriginal dual naming". Tourism Australia. 27 April 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

a dual-naming approach for capital cities

- ^ Cartwright, Lexie (5 July 2021). "Channel 10 commended for NAIDOC weather segment using traditional names for Australian cities". news.com.au. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

traditional names for Australian capital cities

- ^ "Living in Perth". Curtin University. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

state capital city

- ^ Boorloo Kworp : 'Perth is Good', Committee for Perth, June 2020, https://engage.perth.wa.gov.au/55850/widgets/286187/documents/172693, retrieved on 29 January 2023, "Western Australia’s capital"

- ^ "Conferences". Australian Museums and Galleries Association. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

AMaGA holds a National Conference at a different Capital City ... The 2022 AMaGA National Conference will be held in Boorloo Perth

- ^ "National Invasion Day rallies adapt in face of COVID-19". Special Broadcasting Service. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

some capital cities ... Boorloo/Perth

- ^ "The Bachelorette Brooke Blurton thanks supporters from quarantine as she mourns death of her sister". PerthNow. 16 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

tagging WA's capital city by its Aboriginal dual name, Boorloo

- ^ "Easy to promote a place like no other". Business News. 24 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

Boorloo's (Perth's) ... As the state's capital city

- ^ Sandra Bowdler. "The Pleistocene Pacific". Published in 'Human settlement', in D. Denoon (ed) The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders. pp. 41–50. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. University of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Nyungar Boodjar – People's Country". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ "Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243". Federal Court of Australia Decisions. Australasia Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ "Newsletter: Single Noongar appeal—Perth: Bodney v Bennell 2008" (PDF). National Native Title Tribunal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2014.

- ^ "South West Native Title Settlement timeline". Wa.gov.au. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "South West Native Title Settlement - Noongar recognition through an Act of Parliament". Wa.gov.au. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Major, Richard Henry (1859). "Early Voyages to Terra Australis, now called Australia". Project Gutenberg of Australia. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ أ ب Fraser, Gina (November 2015). "A HERITAGE IN NAMES – the Origin and Meaning of Street and Place Names in the City of South Perth" (PDF). City of South Perth. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Appleyard, Reginald T.; Manford, Toby (1979). The Beginning: European Discovery and Early Settlement of Swan River, Western Australia. Nedlands, Western Australia: University of Western Australia Press. ISBN 0-85564-146-0. OCLC 6423026.

- ^ "King George's Sound Settlement". State Records. State Records Authority of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^

Frank H Goldsmith (1951). "The Battle of Pinjara. An Early Incident in Western Australia". Journal and Proceedings. Royal Australian Historical Society. 37: 346. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

The cruel murder of Hugh Nesbit, a nineteen-year-old member of the 21st Regiment Royal Scots Fusiliers near Mandurah on April 16, 1834, was sufficient to touch off the demand for punitive action.

- ^ "Town of Vincent – History". Adapted from 'History of the Town of Vincent', from Town of Vincent 2001 Annual Report, p.52 (possibly based on J. Gentili and others). Town of Vincent. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ ":: REGIONAL WA:: Western Australia: History". Regional Web Australia. 23 December 2003. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ أ ب "History of the City of Perth" (PDF). City of Perth. 23 March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ 'Western Australia. (From the Argyle's Special Correspondent) IV-Perth' (1870, March 18). The Perth Gazette and West Australian Times, p. 3.

- ^ "The Goldrush". The Constitutional Centre of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ Abjorensen, Norman; Docherty, James C. Historical Dictionary of Australia. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. ISBN 9781442245020, p. 292.

- ^ أ ب "Collections in Perth: 4. Colonial Administration". Collections in Perth. National Archives of Australia. 23 August 2007. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Howell, Peter (2002). South Australia and Federation. Adelaide: Wakefield Press. p. 288. ISBN 1-86254-549-9.

- ^ Carmody, Rebecca (29 December 2019). "The forbidden city: When Indigenous people were banned from Perth". ABC News (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Deputy Premier 2nd Collier Government 1933–1935". John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library. 11 May 2005. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Agreement On Oil". West Australian. 4 March 1952. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Stephenson, Gordon; Hepburn, J. A. (1955). Plan for the Metropolitan Region, Perth and Fremantle. Western Australia: Government of Western Australia.

- ^ (1970) Perth – a city of light Perth, W.A. Brian Williams Productions for the Government of WA, 1970 (Video recording) The social and recreational life of Perth. Begins with a 'mock-up' of the lights of Perth as seen by astronaut John Glenn in February 1962

- ^ Gregory, Jenny. "Biography – Sir Henry Rudolph (Harry) Howard – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "City of light - 50 years in Space". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation (15 February 2008). "Moment in Time – Episode 1". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- ^ Moore, Charles (5 November 1998). "Grandfather Glenn's blast from the past". The Daily Telegraph (UK). London. Retrieved 14 July 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "WA Statistical Indicators June 2002". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 11 July 2002. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "Australia's identified mineral resources, 2002" (PDF). Geoscience Australia. 31 October 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2004. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Discussion Paper: Greater Perth Economy And Employment" (PDF). Department for Planning and Infrastructure. 25 August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "Venue Awards". Perth Arena. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Central Park Tower". The Skyscraper Centre — The Global Tall Building Database of the CTBUH. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Allan-Petale, David (25 January 2017). "Boom town to ghost town: Perth CBD vacancies hit 25-year high". WA Today. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Western Australian Climate Services Centre (Bureau of Meteorology) (January 2013). "Perth Metro Climate Averages" (PDF). Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Western Australian Climate Services Centre (Bureau of Meteorology) (January 2013). "Perth Metro Climatic Extremes" (PDF). Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Perth Metro". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Kalamunda". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJandakotAP - ^ "Perth, Australia - Coastal Sea Surface Temperatures". Metoc. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Perth, Australia - UV index". ARPANSA. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Perth, Australia - Perth Metro Climatic Averages" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "3218.0 Historical Population Estimates by Australian Statistical Geography Standard, 1971 to 2011" (XLS). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlandgate map - ^ "Greater Perth". 2011 Census QuickStats. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 March 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "3218.0 - Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2012-13". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةABSGCCSA - ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Community Profile Series : Perth (Statistical Division)". 2006 Census of Population and Housing. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Greater Perth Economy and Employment" (PDF). WA Department of Planning and Infrastructure. 25 August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Structure of the WA Economy" (PDF). WA Department of Treasury and Finance. 24 January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Australian Historical Population Statistics 2008". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

وصلات خارجية

- Watch historical footage of Perth and Western Australia from the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia's collection.

- Historical photos of Perth from the State Library of Western Australia

- Tourism Australia Page

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "note"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="note"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأسترالية-language sources (en-au)

- Articles with dead external links from July 2021

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing نيونگا-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2021

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from April 2022

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2019

- Host cities of the Commonwealth Games

- پرث، أستراليا الغربية

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في 1829

- تأسيسات 1829 في أستراليا

- مدن أستراليا