اللغة اللاتڤية

| Latvian | |

|---|---|

| latviešu valoda | |

| موطنها | Latvia |

| المنطقة | Baltic |

الناطقون الأصليون | (undated figure of 1.3 million)e17 |

الهندو-اوروپية

| |

الصيغ المبكرة | |

| اللاتينية (الأبجدية اللاتڤية) برايل اللاتڤية | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في | |

| ينظمها | Latvian State Language Center |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | lav |

| ISO 639-2 | lav |

| ISO 639-3 | lav – inclusive codeIndividual codes: lvs – اللغة اللاتڤية الفصحى ltg – اللغة اللاتگالية |

| Glottolog | latv1249 |

| Linguasphere | 54-AAB-a |

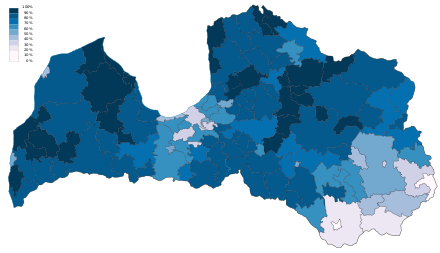

Use of Latvian as the primary language at home in 2011 by municipalities of Latvia | |

اللغة اللاتڤية (latviešu valoda) هي اللغة الرسمية لجمهورية لاتفيا. يستخدمها 1.4 مليون متحدث في لاتفيا وحوالي 150000 خارجها. تنتمي اللغة اللاتفية إلى مجموعة اللغات البلطيقية المتفرعة من عائلة اللغات الهندوأوروبية. وتعتبر اللغة إحدى لغتي البلطيق، بينما اللغة الأخرى هي اللغة الليتوانية. [1] There are about 1.2 million native Latvian speakers in Latvia and 100,000 abroad. Altogether, 2 million, or 80% of the population of Latvia, spoke Latvian in the 2000s, before the total number of inhabitants of Latvia slipped to less than 1.9 million in 2022.[2] Of those, around 1.16 million or 62% of Latvia's population used it as their primary language at home, though excluding the Latgale region it is spoken as a native language in villages and towns by over 90% of the population.[3][4][5]

As a Baltic language, Latvian is most closely related to neighboring Lithuanian (as well as Old Prussian, an extinct Baltic language); however, Latvian has followed a more rapid development.[6] In addition, there is some disagreement whether Latgalian and Kursenieki, which are mutually intelligible with Latvian,[7] should be considered varieties or separate languages.[8]

Latvian first appeared in print in the mid-16th century with the reproduction of the Lord's Prayer in Latvian in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia universalis (1544), in Latin script.

Classification

Latvian belongs to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is one of two living Baltic languages with an official status (the other being Lithuanian). The Latvian and Lithuanian languages have retained many features of the nominal morphology of Proto-Indo-European, though their phonology and verbal morphology show many innovations (in other words, forms that did not exist in Proto-Indo-European),[9] with Latvian being considerably more innovative than Lithuanian. However, Latvian has been also influenced by the Livonian language.[10] For example, Latvian borrowed first-syllable stress from Finno-Ugric languages.[11]

التاريخ

Origins

According to some glottochronological speculations, the Eastern Baltic languages split from Western Baltic (or, perhaps, from the hypothetical proto-Baltic language) between 400 and 600 CE.[12] The differentiation between Lithuanian and Latvian started after 800 CE. At a minimum, transitional dialects existed until the 14th century or 15th century, and perhaps as late as the 17th century.[13]

Latvian as a distinct language emerged over several centuries from the language spoken by the ancient Latgalians assimilating the languages of other neighbouring Baltic tribes—Curonian, Semigallian and Selonian—which resulted in these languages gradually losing their most distinct characteristics. This process of consolidation started in the 13th century after the Livonian Crusade and forced christianization, which formed a unified political, economic and religious space in Medieval Livonia.[14]

16th–18th century

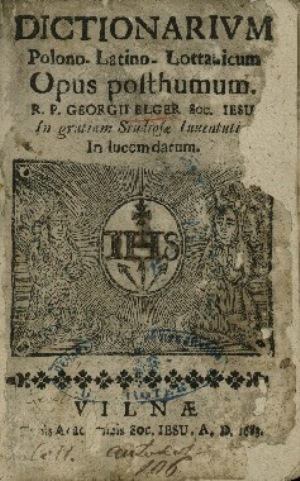

The oldest known examples of written Latvian are from a 1530 translation of a hymn made by Nikolaus Ramm, a German pastor in Riga.[15] The oldest preserved book in Latvian is a 1585 Catholic catechism of Petrus Canisius currently located at the Uppsala University Library.[16]

The first person to translate the Bible into Latvian was the German Lutheran pastor Johann Ernst Glück[17] (The New Testament in 1685 and The Old Testament in 1691). The Lutheran pastor Gotthard Friedrich Stender was a founder of Latvian secular literature. He wrote the first illustrated Latvian alphabet book (1787), the first encyclopedia "The Book of High Wisdom of the World and Nature" (Augstas gudrības grāmata no pasaules un dabas; 1774), grammar books and Latvian–German and German–Latvian dictionaries.

19th century

Until the 19th century, the Latvian written language was influenced by German Lutheran pastors and the German language, because the upper class of local society was formed by Baltic Germans.[6] In the middle of the 19th century the First Latvian National Awakening was started, led by "Young Latvians" who popularized the use of Latvian language. Participants in this movement laid the foundations for standard Latvian and also popularized the Latvianization of loan words. However, in the 1880s, when Czar Alexander III came into power, Russification started.

According to the 1897 Imperial Russian Census, there were 505,994 (75.1%) speakers of Latvian in the Governorate of Courland[18] and 563,829 (43.4%) speakers of Latvian in the Governorate of Livonia, making Latvian-speakers the largest linguistic group in each of the governorates.[19]

20th century

After the death of Alexander III at the beginning of the 20th century, Latvian nationalist movements re-emerged. In 1908, Latvian linguists Kārlis Mīlenbahs and Jānis Endzelīns elaborated the modern Latvian alphabet, which slowly replaced the old orthography used before. Another feature of the language, in common with its sister language Lithuanian, that was developed at that time is that proper names from other countries and languages are altered phonetically to fit the phonological system of Latvian, even if the original language also uses the Latin alphabet. Moreover, the names are modified to ensure that they have noun declension endings, declining like all other nouns. For example, a place such as Lecropt (a Scottish parish) is likely to become Lekropta; the Scottish village of Tillicoultry becomes Tilikutrija.

After Soviet occupation of Latvia, the policy of Russification greatly affected the Latvian language, while the use of Latvian among the Latvians in Russia had already dwindled after the so-called 1937–1938 Latvian Operation of the NKVD during which at least 16,573 ethnic Latvians and Latvian nationals were executed. In the 1941 June deportation and the 1949 Operation Priboi, tens of thousands of Latvians and other ethnicities were deported from Latvia and massive immigration from Russian SFSR, Ukrainian SSR, Byelorussian SSR and other republics of the Soviet Union followed, largely as a result of Stalin's plan to integrate Latvia and the other Baltic republics into the Soviet Union by means of colonization. As a result, the proportion of the ethnic Latvian population within the total population was reduced from 80% in 1935 to 52% in 1989. In Soviet Latvia, most of the immigrants who settled in the country did not learn Latvian. According to the 2011 census Latvian was the language spoken at home by 62% of the country's population.[3][4]

After the re-establishment of independence in 1991, a new policy of language education was introduced. The primary declared goal was the integration of all inhabitants into the environment of the official state language while protecting the languages of Latvia's ethnic minorities.[20]

Government-funded bilingual education was available in primary schools for ethnic minorities until 2019 when Parliament decided on educating only in Latvian. Minority schools are available for Russian, Yiddish, Polish, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Estonian and Roma schools. Latvian is taught as a second language in the initial stages too, as is officially declared, to encourage proficiency in that language, aiming at avoiding alienation from the Latvian-speaking linguistic majority and for the sake of facilitating academic and professional achievements. Since the mid-1990s, the government may pay a student's tuition in public universities only provided that the instruction is in Latvian. Since 2004, the state mandates Latvian as the language of instruction in public secondary schools (Form 10–12) for at least 60% of class work (previously, a broad system of education in Russian existed).[21]

The Official Language Law was adopted on 9 December 1999.[22] Several regulatory acts associated with this law have been adopted. Observance of the law is monitored by the Latvian State Language Center run by the Ministry of Justice.

21st century

To counter the influence of Russian and English, government organizations (namely the Terminology Commission of the Latvian Academy of Science and the State Language Center) popularize the use of Latvian terms. A debate arose over the Latvian term for euro. The Terminology Commission suggested eira or eirs, with their Latvianized and declinable ending, would be a better term for euro than the widely used eiro, while European Central Bank insisted that the original name euro be used in all languages.[23] New terms are Latvian derivatives, calques or new loanwords. For example, Latvian has two words for "telephone"—tālrunis and telefons, the former being a direct translation into Latvian of the latter international term. Still, others are older or more euphonic loanwords rather than Latvian words. For example, "computer" can be either dators or kompjūters. Both are loanwords; the native Latvian word for "computer" is skaitļotājs, which is also an official term. However, now dators has been considered an appropriate translation, skaitļotājs is also used.

There are several contests held annually to promote the correct use of Latvian. One of them is "Word of the year" (Gada vārds) organized by the Riga Latvian Society since 2003.[24] It features categories such as the "Best word", "Worst word", "Best saying" and "Word salad". In 2018 the word zibmaksājums (instant payment) won the category of "Best word" and influenceris (influencer) won the category of "Worst word".[25] The word pair of straumēt (stream) and straumēšana (streaming) were named the best words of 2017, while transporti as an unnecessary plural of the name for transport was chosen as the worst word of 2017.[26]

Dialects

There are three dialects in Latvian: the Livonian dialect, High Latvian and the Middle dialect. Latvian dialects and their varieties should not be confused with the Livonian, Curonian, Semigallian and Selonian languages.

اللهجة الليڤونية

Orthography

Standard orthography

اليوم، الأبجدية القياسية اللاتڤية تتكون من 33 حرف:

| A | Ā | B | C | Č | D | E | Ē | F | G | Ģ | H | I | Ī | J | K | Ķ | L | Ļ | M | N | Ņ | O | P | R | S | Š | T | U | Ū | V | Z | Ž |

| a | ā | b | c | č | d | e | ē | f | g | ģ | h | i | ī | j | k | ķ | l | ļ | m | n | ņ | o | p | r | s | š | t | u | ū | v | z | ž |

Old orthography

Comparative orthography

For example, the Lord's Prayer in Latvian written in different styles:

| First orthography (Cosmographia Universalis) |

Old orthography[27] | Modern orthography | Internet style | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muuſze Thews exkan tho Debbes | Muhſu Tehvs debbeſîs | Mūsu tēvs debesīs | Muusu teevs debesiis | |

| Sweetyttz thope totws waerdtcz | Swehtits lai top taws wahrds | Svētīts lai top tavs vārds | Sveetiits lai top tavs vaards | |

| Enaka mums touwe walſtibe. | Lai nahk tawa walſtiba | Lai nāk tava valstība | Lai naak tava valstiiba | |

| Tows praetcz noteſe | Taws prahts lai noteek | Tavs prāts lai notiek | Tavs praats lai notiek | |

| ka exkan Debbes tha arridtczan wuerſſon ſemmes | kà debbeſîs tà arirdſan zemes wirsû | kā debesīs, tā arī virs zemes | kaa debesiis taa arii virs zemes | |

| Muſze beniſke mayſe bobe mums ſdjoben. | Muhsu deeniſchtu maizi dod mums ſchodeen | Mūsu dienišķo maizi dod mums šodien | Muusu dienishkjo maizi dod mums shodien | |

| Vnbe pammet mums muſſe parrabe | Un pametti mums muhſu parradus [later parahdus] | Un piedod mums mūsu parādus | Un piedod mums muusu paraadus | |

| ka mehs pammettam muſſims parabenekims | kà arri mehs pamettam ſaweem parrahdneekeem | kā arī mēs piedodam saviem parādniekiem | kaa arii mees piedodam saviem paraadniekiem | |

| Vnbe nhe wedde mums exkan kaerbenaſchenne | Un ne eeweddi muhs eekſch kahrdinaſchanas | Un neieved mūs kārdināšanā | Un neieved muus kaardinaashanaa | |

| Seth atpeſthmums no to loune | bet atpeſti muhs no ta launa [later łauna] | bet atpestī mūs no ļauna | bet atpestii muus no ljauna | |

| Aefto thouwa gir ta walſtibe | Jo tew peederr ta walſtiba | Jo tev pieder valstība | Jo tev pieder valstiiba. | |

| vnbe tas ſpeez vnb tas Goobtcz tur muſſige | un tas ſpehks un tas gods muhſchigi [later muhzigi] | spēks un gods mūžīgi | speeks un gods muuzhiigi | |

| Amen | Amen | Āmen | Aamen |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | [ŋ] | |

| Stop | p b | t d | c ɟ | k ɡ | |

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | |||

| Fricative | (f) v | s z | ʃ ʒ | (x) | |

| Approximant | j | ||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | |||

| Trill | r |

The consonant sounds /f x/ are only found in loanwords. [ŋ] is only an allophone of nasals before velars.

Latvian plosives are not aspirated (unlike in English and other Germanic languages).

Vowels

Latvian has six vowels, with length as distinctive feature:

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Mid | ɛ | ɛː | (ɔ) | (ɔː) | ||

| Open | æ | æː | a | aː | ||

/ɔ ɔː/, and the diphthongs involving it other than /uɔ/, are confined to loanwords.

عبارات أساسية

| العبارة | الترجمة |

|---|---|

| Latviešu | اللغة اللاتفية |

| Sveicināti | مرحباً |

| Labrīt | صباح الخير |

| Labvakar | مساء الخير |

| Uz redzēšanos | وداعاً |

| Lūdzu | رجاءً |

| Paldies | شكراً |

| Jā | نعم |

| Nē | لا |

| Atvainojiet | عفواً |

| Es nesaprotu | لا أفهم |

الهامش

- ^ "EU official languages". European-union.europa.eu. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "Dažādu tautu valodu prasme". vvk.lv (in اللاتفية).

- ^ أ ب "At Home Latvian Is Spoken by 62% of Latvian Population; the Majority – in Vidzeme and Lubāna County" (in الإنجليزية). Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Latvian Language Is Spoken by 62% of the Population" (in الإنجليزية). Baltic News Network. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Žemaitis, Augustinas. "Languages". OnLatvia.com. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ أ ب Dahl, Östen; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria, eds. (2001). The Circum-Baltic Languages (in الإنجليزية). John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027230579. OCLC 872451315.

- ^ "How Latgale chose to join Latvia". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

The Latgalian language falls within the High Latvian dialect and is of course mutually intelligible with the other dialects.

- ^ "Latgalian Language in Latvia: Between Politics, Linguistics and Law". International Centre for Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity. 30 March 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ For example the Latvian debitive verb form (man ir jāmācās “I must study” or “it is necessary for me to study”) and the Lithuanian frequentative past (jie eidavo “they used to go”).Baltic languages - Comparison of Lithuanian and Latvian Archived 2021-10-25 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ "Livones.net - Mutual influence between Livonian and Latvian".

- ^ Stafecka, Anna (2014). "Baltic and Finnic linguistic relations reflected in geolinguistic studies of the Baltic languages".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ International Business Publications, Usa. (2008). Lithuania taxation laws and regulations handbook. Intl Business Pubns Usa. p. 28. ISBN 978-1433080289. OCLC 946497138.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo (1998). "The Baltic Languages". The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. pp. 454–479. ISBN 9781134921867. OCLC 908192063.

- ^ "Livonia. 13th-16th Century". Archived from the original on 2017-10-27. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Vīksniņš, Nicholas (1973). "The Early History of Latvian Books". Lituanus. 19 (3). Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ "National treasure: The oldest Latvian-language book in Rīga". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Rozenberga, Māra; Sprēde, Antra (24 August 2016). "National treasure: The first Bible in Latvian". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 – Courland governorate". Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 – Governorate of Livonia". Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Minority Protection in Latvia (PDF). Open Society Institute. 2001. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Latvian Centre for Human Rights and Ethnic Studies (2004). Analytical Report PHARE RAXEN_CC - Minority Education (PDF). Vienna: Minority Education in Latvia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ "Official Language Law". likumi.lv. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "No 'eira' - but 'eiro' will do". The Baltic Times. 6 October 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "'Glābējsilīte' is word of the year". Latvians Online. 18 January 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Best and worst words of 2018 underlined". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "Best and worst words of 2017 underlined". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. 31 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ BIBLIA, published Riga, 1848 (reprint), original edition 1739; "modern" old orthographies published into the 20th century do not double consonants

للاستزادة

- Derksen, Rick (1996). "Metatony in Baltic". Amsterdam: Rodopi.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- Latvian Language Law in English

- Letonika

- Overview of the Latvian Language (en)

- State (Official) Language Commission (linguistic articles, applicable laws, etc.)

- English–Latvian / Latvian–English dictionary

- English-Latvian and Latvian–English online translation

- Latvian–English Dictionary from Webster's Online Dictionary – The Rosetta Edition

- National Agency for Latvian Language Training

- The Latvian Alphabet

- Examples of Latvian words and phrases (with sound)

- Languages of the World:Latvian

- Latvian bilingual dictionaries

- Latvian Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- CS1 اللاتفية-language sources (lv)

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Languages without family color codes

- Language articles with 'no date' set

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Languages with ISO 639-1 code

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2022

- Articles containing لاتڤية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- بذرة لسانيات

- اللغة اللاتڤية

- لغات لتوانيا

- لغات بلاروس

- لغات روسيا

- Subject–verb–object languages

- لغات لاتفيا