ظاظا (شعب)

| |

| إجمالي التعداد | |

|---|---|

| 2 إلى 3 مليون[1][2] | |

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |

الشتات: ح. 300.000[2] أستراليا،[3] النمسا،[4] بلجيكا،[4] فرنسا،[4] Germany,[3] هولندا،[4] السويد،[4] سويسرا،[4] المملكة المتحدة،[5] الولايات المتحدة.[3] | |

| اللغات | |

| الظاظا، الكردية،[6] التركية. | |

| الدين | |

| مسلمون سنة،[7] علويون |

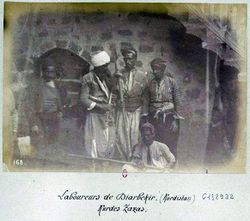

الظاظا أو الزازا (أو الكـِرد، الكرمانج أو الدميلي)[8][9]، هم شعوب تعيش في شرق الأناضول ويتحدثون الزازاكية. موطنهم الأصلي منطقة درسيم، والتي تتألف من محافظتي تونجايلي، بينگول ومناطق من محافظة الازيغ، إرزنجان ودياربكر. يعتبر معظم الزازا أنفسهم كرديو العرقية، جزء من الأمة الكردية،[3][10][11][12] معادة ما يوصفون بأكراد الزازا.[9][13][14][15]

الديموغرافيا

الأعداد الحقيقية للزازا غير معروفة، نظراً لغياب بيانات تعداد حديثة ودقيقة. أحدث الاحصائيات الرسمية للغة الأصلية متوافرة لسنوات 1965، حيث اختار 147.707 (0.5%) الزازاز كلغتهم الأصلية في تركيا.[16] كما تجدر الإشارة إلى أن الكثير من الزازا لا يعرفون سوى الكردية (القرمانجية)، حيث يعتقدون أن لغة الزازا ما هي إلا فرع لللغة الكردية.[6] تبعاً لمسح كوندا من مارس 2007، يشكل الأكراد والزازا معاً 13.4% من السكان البالغين و15.68% من إجمالي السكان في تركيا.[17]

الوعي العرقي

While Zazas largely consider themselves Kurds,[18] some researches consider Zazas to be a separate ethnic group, and treat them as such in their academic work.[19] A scientific report from 2005 concluded that Zazas share the same genetical pattern as other Kurdish groups and did not support the hypothesis of Zazas originating from Northern Iran.[20]

الظاظا والكرد الناطقون بالكرمانجي

Kurmanji-speaking Kurds and Zazas have for centuries lived in the same areas in Anatolia. In the 1920s and 1930s, Zazas played a key role in the rise of Kurdish nationalism with their rebellions against the Ottoman Empire and later the Republic of Turkey. Zazas participated in the Koçgiri rebellion in 1920,[22] and during the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925, the Zaza Sheikh Said and his supporters rebelled against the newly established Republic because of its Turkish nationalist and secular ideology.[23] Many Zazas subsequently joined the Kurmanji-speaking Kurdish nationalist Xoybûn, the Society for the Rise of Kurdistan, and other movements, where they often rose to prominence.[24]

In 1937 during the Dersim rebellion, Zazas once again rebelled against the Turks. This time the rebellion was led by Seyid Riza and ended with a massacre of thousands of Kurmanji-speaking Kurds and Zaza civilians, while many were internally displaced due to the conflict.[25]

Sakine Cansız, a Zaza from Tunceli was a founding member of Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), and like her many Zazas joined the rebels, including the promiment Besê Hozat.[26][27] Many Zaza politicians are also to be found in the fraternal Kurdish parties of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) and Democratic Regions Party (DBP), like Selahattin Demirtaş, Aysel Tuğluk, Ayla Akat Ata and Gültan Kışanak.

On the other hand, some Zazas have publicly stated they do not consider themselves Kurdish, including Hüseyin Aygün, a CHP politician from Tunceli.[28][29]

الجذور التاريخية للزازا

اللغة

Zaza is a Zaza–Gorani language, spoken in the east of modern Turkey, with approximately 2 to 3 million speakers. There is a division between Northern and Southern Zaza, most notably in phonological inventory, but Zaza as a whole forms a dialect continuum, with no recognized standard.[32] The first written statements in the Zaza language were compiled by the linguist Peter Lerch in 1850. Two other important documents are the religious writings of Ehmedê Xasi of 1898,[33] and of Usman Efendiyo Babıc (published in Damascus in 1933); both of these works were written in Arabic script.[34] The state-owned TRT Kurdî airs shows in Zaza.[35]

During the 1980s, the Zaza language became popular among the Zaza diaspora, followed by publications in Zaza in Turkey.[36]

الدين

A small minority of the Zaza population adhere to a branch of Alevism and they predominantly live around Tunceli. While predominantly of Zazas adhere to Sunni Islam, both Hanafi and Shafi‘i,[37] whereas the Shafi‘i followers are mostly Naqshbandi.[38] Historically, a small Christian Zaza population existed in Gerger.[39]

قومية الزازا

Zaza nationalism is an ideology that supports the preservation of Zaza people between Turks and Kurds in Turkey. Turkish nationalist Hasan Reşit Tankut proposed in 1961 to create a corridor between Zaza-speakers and Kurmanji-speakers to hasten Turkification. In some cases in the diaspora, Zazas turned to this ideology because of the more visible differences between them and Kurmanji-speakers.[40] Zaza nationalism was further boosted when Turkey abandoned its assimilatory policies which made some Zazas begin considering themselves as a separate ethnic group.[41] In the diaspora, some Zazas turned to Zaza nationalism in the freer European political climate. On this, Ebubekir Pamukchu, the founder of the Zaza national movement stated: "From that moment I became Zaza."[42] Zaza nationalists fear Turkish and Kurdish influence and aim at protecting Zaza culture and language rather than seeking any kind of autonomy within Turkey.[43]

According to researcher Ahmet Kasımoğlu, Zaza nationalism is a Turkish and Armenian attempt to divide Kurds.[44]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ Duus (EDT) Extra, D. (Durk) Gorter, Guus Extra, The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives, Multilingual Matters (2001). ISBN 1-85359-509-8. p. 415. Cites two estimates of Zaza-speakers in Turkey, 1,000,000 and 2,000,000, respectively. Accessed online at Google book search.

- ^ أ ب "Dimlï". IranicaOnline. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Arakelova, Victoria (1999). "The Zaza People as a New Ethno-Political Factor in the Region": 397. JSTOR 4030804.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Selim, Zülfü. "Zaza Dilinin Gelişimi" (PDF) (in Turkish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Turkey's Zaza gearing up efforts for recognition of rights". Hürriyet Daily News. 23 May 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Turkey: The Country's Zaza are Speaking Out About their Language". Eurasianet.org. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Paul Joseph White, Joost Jongerden. Turkey's Alevi Enigma: A Comprehensive Overview. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9789004125384.

- ^ Lezgîn, Roşan. "Among Social Kurdish Groups – General Glance at Zazas". Zazaki.net.

- ^ أ ب Malmisanij (1996). "Kird, Kirmanc, Dimili or Zaza Kurds". Istanbul: Deng Publishing.

- ^ Kehl-Bodrogi; Otter-Beaujean; Barbara Kellner-Heikele (1997). Syncretistic religious communities in the Near East : collected papers of the international symposium "Alevism in Turkey and comparable syncretistic religious communities in the Near East in the past and present", Berlin, 14-17 April 1995. Leiden: Brill. p. 13. ISBN 9789004108615.

- ^ Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina (October 1999). "Kurds, Turks, or a People in their own Right? Competing Collective Identities Among the Zazas". The Muslim World. 89 (3–4): 442. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1999.tb02757.x.

- ^ Nodar Mosaki (14 March 2012). "The zazas: a kurdish sub-ethnic group or separate people?". Zazaki.net. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Taylor, J. G. (1865). "Travels in Kurdistan, with Notices of the Sources of the Eastern and Western Tigris, and Ancient Ruins in Their Neighbourhood". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 35: 39. doi:10.2307/3698077.

- ^ van Bruinessen, Martin. "The Ethnic Identity of the Kurds in Turkey" (PDF): 1. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Özoğlu, Hakan (2004). Kurdish notables and the Ottoman state : evolving identities, competing loyalties, and shifting boundaries. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5993-4.

- ^ "UN Demographic Yearbooks". Unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ^ "55 milyon kişi 'etnik olarak' Türk". Miliyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Kehl-Bodrogi (1999), p. 442.

- ^ Keskin (2015), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Nasidze et al. (2005).

- ^ Chantre (1881).

- ^ Lezgîn (2010).

- ^ Kaya (2009), p. IX.

- ^ Kasımoğlu (2012), pp. 653–657.

- ^ Cengiz (2011).

- ^ Milliyet (2013).

- ^ Hürriyet (2013).

- ^ Haber Vaktim (2011).

- ^ Haber Türk (2013).

- ^ Gippert (1999).

- ^ Keskin, Mesut. Zazaca Üzerine Notlar قالب:Webarşiv

- ^ Endangered Language Alliance.

- ^ Malmîsanij (1996), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Keskin (2015), p. 108.

- ^ Ziflioğlu (2011).

- ^ Bozdağ & Üngör (2011).

- ^ Werner (2012), pp. 24 & 29.

- ^ Kalafat (1996), p. 290.

- ^ Werner (2012), p. 25.

- ^ van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (28 January 2009). "Is Ankara Promoting Zaza Nationalism to Divide the Kurds?". Terrorism Focus. 6 (3). Retrieved 1 April 2017. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "wilgenburg" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "wilgenburg" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Indigenous Peoples: An Encyclopedia of Culture, History, and Threats to . Victoria R. Williams

- ^ Arakelova (1999), p. 401.

- ^ Zulfü Selcan, Grammatik der Zaza-Sprache, Nord-Dialekt (Dersim-Dialekt), Wissenschaft & Technik Verlag, Berlin, 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Kasımoğlu (2012), p. 654.

]