أندروس

Andros

Περιφερειακή ενότητα / Δήμος Άνδρου | |

|---|---|

Andros town | |

Andros within the South Aegean | |

| الإحداثيات: 37°50′11″N 24°53′53″E / 37.83639°N 24.89806°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Region | South Aegean |

| Capital | Andros (town) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 380 كم² (150 ميل²) |

| التعداد (2011) | |

| • الإجمالي | 9٬221 |

| • الكثافة | 24/km2 (63/sq mi) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal codes | 845 xx |

| Area codes | 22820 |

| Car plates | EM |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

أندروس (باليونانية: Άνδρος؛ تـُنطق [ˈanðros] ؛ إنگليزية: Andros) هي الجزيرة الأقصى شمالاً في أرخبيل الكيكلادس اليوناني، على بعد نحو 10 كم جنوب شرق Euboea, and about 3 km (2 mi) north of Tinos. It is nearly 40 km (25 mi) long, and its greatest breadth is 16 km (10 mi). It is for the most part mountainous, with many fruitful and well-watered valleys.[1] The municipality, which includes the island Andros and several small, uninhabited islands, has an area of 380 km2 (146.719 sq mi).[2] The largest towns are Andros (town), Gavrio, Batsi, and Ormos Korthiou.

Palaeopolis, the ancient capital, was built into a steep hillside, and the breakwater of its harbor can still be seen underwater. At the village of Apoikia, there is the notable spring of Sariza, where the water flows from a sculpted stone lion's head. Andros also offers great hiking options with many new paths being added each year.

التاريخ

القِدم

During the Final Neolithic (over 5,000 years ago), Andros had a fortified village on its west coast, which archaeologists have named Strofilias, after the plateau on which it was built. Strofilias was related to the "Attica-Kephala" culture, and predates the Cycladic culture of the Bronze Age. It was an important maritime center and one of the earliest examples of fortification in Greece. It is notable for rock carvings on its walls, which include animals such as jackals, goats, deer, fish and dolphins, as well as a depiction of a flotilla of ships.[3] The island in ancient times contained an Ionian population, perhaps with an admixture of Thracian ancestry.[بحاجة لمصدر] Though it has been proposed that Andros was originally dependent on Eretria,[بحاجة لمصدر] by the 7th century BC it had become sufficiently prosperous to send out several colonies, to Chalcidice (Acanthus, Stageira, Argilus, Sane). The ruins of Palaeopolis, the ancient capital, are on the west coast; the town possessed a famous temple, dedicated to Dionysus. In 480 BC, it supplied ships to Xerxes and was subsequently harried by the Greek fleet. Though enrolled in the Delian League, it remained disaffected towards Athens, and in 477 had to be coerced by the establishment of a cleruchy on the island; nevertheless, in 411 Andros proclaimed its freedom, and in 408 withstood an Athenian attack. As a member of the second Delian League, it was again controlled by a garrison and an archon. In the Hellenistic period, Andros was contended for as a frontier-post by the two naval powers of the Aegean Sea, Macedon and Ptolemaic Egypt. In 333, it received a Macedonian garrison from Antipater; in 308 it was freed by Ptolemy I of Egypt. In the Chremonidean War (266–263) it passed again to Macedon after a battle fought off its shores.[1] The Ptolemaic empire was at its height, with a considerable fleet stationed at Andros.[4]

In 200, it was captured by a combined Roman, Pergamene and Rhodian fleet, and remained a possession of the Kingdom of Pergamon until the dissolution of that kingdom in 133 BC, when it was granted to Rome.[1][5]

العصور الوسطى

During the long centuries of Byzantine rule, Andros was relatively obscure. First part of the Roman province of the Islands, it later became part of the theme (Byzantine district) of the Aegean Sea.[5] Like other Aegean islands, it suffered Saracen raids,[5] but during the Komnenian period the island flourished due to its silk production, exporting gossamer and velvet fabrics to Western Europe.[5][6]

Andros was captured by the Fourth Crusade on its way to Constantinople in 1203.[7] After the fall of Constantinople in 1204, the island was slated to come under control of the Republic of Venice according to the Partitio Romaniae;[8][9] in 1207 it became part of the Duchy of the Archipelago under Marco I Sanudo, who in turn gave it to Marino Dandolo as a sub-fief.[10][11] Probably sometime around 1239, Dandolo was expelled from the island by Geremia Ghisi, ruler of Skiathos, Skopelos, and Skyros. Dandolo died soon after and a case was brought before the Venetian courts against Ghisi by Dandolo's widow Felisa and his sister Maria Doro. Felisa was soon aided by the influential lord of Astypalaia, Jacopo Querini, who became her second husband. Although the Venetian court found in their favour in August 1243 and ordered the Ghisi brothers to give up Andros, this did not happen. The case dragged on until after Geremia's death, when Duke Angelo Sanudo took over the island. He eventually gave half of it, according to the feudal law current in Latin Greece, to Felisa.[12][13] The case took on new life after Felisa died and no claimant made appearance. Duke Marco II Sanudo then reverted the entire island to the ducal domain, but just two days before the legal deadline of two years and two days had passed, Marino's grandson Nicholas Querini appeared in Naxos to claim his inheritance. The case was again brought before the courts of Venice, but Sanudo disputed the Republic's authority over his domain. The case was eventually settled through the mediation of Nicolò Giustinian, the Venetian bailo of Negroponte in 1291–93, whereby Querini renounced his claims in exchange for a cash payment of 5,000 pounds.[14][15] Thus Andros remained in the hands of the Sanudo dukes, who henceforth styled themselves "Lords of the duchy of Naxos and Andros" and occasionally chose the castle of Andros as their residence.[16] In 1292, Andros, along with other of the Cyclades, was raided by the Aragonese fleet under Roger de Lluria.[17]

In December 1371, the island was granted as a fief to Maria Sanudo, half-sister of the last Sanudo duke, Nicholas III dalle Carceri.[18] In 1383, Nicholas III was murdered and Francesco I Crispo became the new duke, giving Andros with Syros to his daughter and her husband, Pietro Zeno, the son of the Venetian bailo of Negroponte.[19] Zeno was a very able diplomat,[20] but even he found it difficult to manoeuvre among the various competing powers of the era. Unlike Syros, Paros, and other islands, which had been left destitute and almost depopulated by the Ottoman raids, Andros managed to escape relatively unscathed, but in return Zeno was forced to pay tribute and provide harbour and shelter for the Turkish ships. Nevertheless, in 1416, the island was raided and almost the entire population carried off by the Ottomans.[21] At about the same time Arvanites crossed from Euboea over into the island, settling in its northern part.[22]

In 1431, when the Venetians ravaged the Genoese colony of Chios, the Genoese seized Andros and Naxos, both under Venetian protection, in retaliation, and only adroit diplomacy by the dukes of the Archipelago managed to prevent the islands' outright annexation by Genoa.[23] In 1427, Pietro Zeno died, and was succeeded by his son Andrea, who was of poor health and only had a daughter. In 1437, Andrea too died, and the island was seized by Andrea's uncles, who aimed to wed Andrea's daughter to their son when she came of age, and thus legalize their control of Andros. Venice quickly reacted and took over the island, installing a governor there while her courts heard the cases of all the claimants. One of them was Maria Sanudo's son Crusino I Sommaripa, Lord of Paros and Triarch of Negroponte. Like his mother, he never abandoned his claims on the island, and eventually was vindicated by the Venetian courts. After compensating the Zeno family, he took possession of the island in 1440.[24][25]

Andros suffered once again heavily from Turkish attacks during the Ottoman–Venetian War of 1463–1479. In 1468 four ships attacked the island, killing baron Giovanni Sommaripa and carrying off numerous prisoners and booty worth 15,000 ducats. Two years later the Ottomans raided the island again, carrying off so many of its population that the island was left with 2,000 inhabitants.[26] Despite these disasters, the two Sommaripa possessions of Andros and Paros remained the most prosperous islands in the Cyclades in the period, and the Sommaripa rulers of Andros acted independently of their theoretical suzerain at Naxos, even to the point of claiming the title of duke for themselves.[27] By the 1500s, however, the two Sommaripa branches of Andros and Paros were at war with each other, as a result of which many Andrians were carried off to Paros. In addition, the Andrians suffered from the cruelty of their own "duke", Francesco, to the point that they sent an embassy to Venice threatening to call in the Turks if nothing was done. The Venetians responded by removing Francesco to Venice in 1507, and installing a governor of their own for the next seven years.[28]

In the event, Sommaripa rule was restored when Venice recognized Alberto Sommaripa as the rightful heir.[29] The island was seized by the Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa in 1537, but Crusino III Sommaripa managed to regain it through the intercession of the French ambassador, in exchange for an annual tribute of 35,000 akçes to the Ottoman governor at Negroponte.[30]

العصر العثماني

When the Ottomans annexed Naxos in 1566, at the behest of the local Greeks, the Andrians too decided to rise up against their ruler, Gianfrancesco Sommaripa. Although the latter managed to escape with his life, Andros too now came under Ottoman control.[31] For the next thirteen years, the entirety of the former Duchy of the Archipelago was granted to the Sultan's favourite, Joseph Nasi, who ruled the islands via representatives and was mostly concerned with using them as a source of wealth.[32] Upon Nasi's death, the Greeks of Andros and Naxos requested from the Sultan that the descendants of their old dynasties be restored as Turkish vassals, but in the end, the islands were directly annexed as a province; in 1580, however, the Cyclades were granted a charter of privileges that granted them considerable local autonomy, low taxes and religious freedom, a situation that remained throughout the period of Ottoman rule.[33] In the early 1770s, during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74, the island was occupied by the Russians and used as a base for their operations in the Aegean.[5]

العصر الحديث

On May 10, 1821, Theophilos Kairis, one of the leading Greek intellectuals, declared the island's participation in the Greek War of Independence by raising the Greek flag at the Church of St George.[5] At this time, a famous heartfelt speech, or "ritoras" (ρήτορας), inspired shipowners and merchants to contribute funds to build a Greek Navy to combat the Ottomans. At the end of the war, the island became part of the independent Kingdom of Greece.

Following Independence, Andros became a major centre of Greek shipping. In this it was helped by the arrival of refugees from Psara, and the decline of other traditional shipping centres such as Galaxeidi and Hydra Island. Andrian merchants were particularly active in the grain trade from central and eastern Europe conducted from the Danube estuary. Initially locally constructed, Andrian ships were later built at Syros, especially as shipping began the transit to steam. By 1914, Andrian-registered shipping was second in Greece in terms of capacity. After World War I, the local registered ships rose from 25 (1921) to 80 before World War II. The losses suffered during the latter, as well as the internationalization of shipping and emigration of the ship-owning families to Piraeus and London, signalled the end of Andrian shipping.[34]

الادارة

Andros is a separate regional unit of the South Aegean region, and the only municipality of the regional unit. As part of the 2011 Kallikratis government reform, the regional unit Andros was created out of part of the former Cyclades Prefecture. At the same reform, the current municipality Andros was created out of the 3 former municipalities:[35]

المقاطعة

The province of Andros (باليونانية: Επαρχία Άνδρου) was one of the provinces of the Cyclades Prefecture. Its territory corresponded with that of the current regional unit Andros.[36] It was abolished in 2006.

التعداد

Andros, the capital, on the east coast, had about 2,000 inhabitants in 1900. The island had about 18,000 inhabitants in (1900). The 1991 census read 8,781. According to the latest Greek census of 2011, the town of Andros still numbered 1,665 inhabitants, and the island's total was 9,221. The island is composed of the municipal units of Andros (town) (pop. 3,901), Korthio (pop. 1,948), and Ydrousa (pop. 3,372). The north of Andros has a small Arvanite community. The name of the island in Arvanitika is Ε̰νdρα, Ëndra.[37]

Communities and settlements

- Aladinon

- Apoikia

- Ammolochos

- Andros (Chora)

- Ano Aprovato

- Ano Gavrio

- Arnas

- Batsi

- Epano Fellos

- Gavrio

- Gides

- Kalyvari

- Kaparia

- Katakilo

- Kipri

- Kochylos

- Lamira

- Livadia

- Makrotantalo

- Mermingies

- Mesaria

- Ormos Korthiou

- Palaiokastro

- Palaiopolis

- Piso Meria

- Pitrofos

- Sineti

- Stenies

- Varidio

- Vitalio

- Vouni

- Vourkoti

- Ypsilou

- Zaganiaris

- Strapouries

السينما

أشخاص بارزون

- Amphis (4th century BC), comic poet

- Matthew, Patriarch of Alexandria

- Theophilos Kairis (1784–1853), scholar, teacher, priest and revolutionary

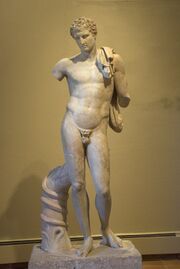

- Michalis Tombros (1889–1974), sculptor

- Nikitas Kaklamanis (1946–present), doctor and politician, mayor of Athens

- George Leonardos (1937–present), journalist and author, awarded with the Greek State Literature Award 2008

- Yiannis Tridimas (born 1945), established UK long-distance runner

- Alexander Pantages (1875–1936), American vaudeville magnate

- Andreas Embirikos (1901–1975), Greek surrealist poet and the first Greek psychoanalyst

- Michael Dertouzos (1936–2001), Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Director of the M.I.T. Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS) from 1974 to 2001.

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت Chisholm 1911.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in اليونانية). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- ^ Liritzis, I, Strofilias (Andros Island, Greece): new evidence for the cycladic final neolithic period through novel dating methods using luminescence and obsidian hydration, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 37, Issue 6, June 2010, Pages 1367–1377

- ^ Hughs, Benjamin Acousta (2012). Callimachus in Context. Cambridge: United Kingdom University Press. ISBN 978-1107470644.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Andros, Chapter 2: History". Cultural Portal of the Aegean Archipelago. Foundation of the Hellenic World. 28 April 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)[dead link] - ^ Freely 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Setton 1976, p. 9.

- ^ Setton 1976, p. 18.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 29, 579.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 44, 579.

- ^ Setton 1976, p. 19 (note 78), 428.

- ^ Setton 1976, pp. 429–431.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 578–579.

- ^ Setton 1976, pp. 431–432.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 579–580.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 580.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 581.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 592.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 593–595.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 596, 604.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 598–599, 603.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 600.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 603.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 595, 604–605.

- ^ Setton 1978, p. 93 (note 47).

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 611.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 617.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 619.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 621.

- ^ Miller 1908, p. 628.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 634–636.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 637–643.

- ^ Miller 1908, pp. 643–644.

- ^ "Andros, Chapter 5: Shipping on Andros". Cultural Portal of the Aegean Archipelago. Foundation of the Hellenic World. 28 April 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)[dead link] - ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in اليونانية). Government Gazette.

- ^ "Detailed census results 1991" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. (39 MB) (in Greek and فرنسية)

- ^ Jochalas, Titos P. (1971): Über die Einwanderung der Albaner in Griechenland: Eine zusammenfassene Betrachtung ["On the immigration of Albanians to Greece: A summary"]. München: Trofenik.

المراجع

- "Large Bronze Age Town Unearthed On Andros." New York, N.Y.:Hellenic Times. Sep 2- 30, 2005. Vol. XXXII, Iss. 11; pg. 2. ISSN 1059-2121 (link)

- Freely, John (2006). The Cyclades: Discovering the Greek Islands of the Aegean. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1845111605.

- Miller, William (1908). The Latins in the Levant, a History of Frankish Greece (1204–1566). New York: E.P. Dutton and Company.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume I: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-114-0.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1978). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume II: The Fifteenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-127-2.

إعزاء الفضل:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 2 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

وصلات خارجية

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), 1878, p. 23

- Official website of Municipality of Ándros (in إنگليزية and Greek)

- Official website of Municipality of Korthío (in إنگليزية and Greek)

- Andros365 e-mag of Andros Island (in إنگليزية and Greek)

- Richard Stillwell, ed. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, 1976: "Andros, one of the Cyclades, Greece"

- Latest News (in Greek)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 اليونانية-language sources (el)

- CS1 errors: deprecated parameters

- Articles with dead external links from October 2018

- Articles with Greek-language sources (el)

- Articles with فرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2014

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2018

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from EB9

- Articles with إنگليزية-language sources (en)

- أندروس

- Municipalities of the South Aegean

- مراكز اليونان

- أعضاء العصبة الدلية

- Populated places in Andros