اضمحلال الدولة العثمانية

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| تاريخ الدولة العثمانية |

|---|

|

| البزوغ (1299–1453) |

| ما بين السلاطين (1402–1413) |

| النمو (1453–1606) |

| الركود (1606–1699) |

| سلطنة الحريم |

| فترة كوپريلي (1656–1703) |

| الاضمحلال (1699–1792) |

| فترة التيوليپ (1718–1730) |

| الانحلال (1792–1923) |

| فترة التنظيمات (1839–1876) |

| فترة المشروطية الأولى |

| فترة المشروطية الثانية |

| التقسيم |

|

|

اضمحلال الدولة العثمانية (1828–1908) هي الفترة التي أعقبت ركود الدولة العثمانية (1683–1827) التي شهدت فيها الدولة عدة نكسات اقتصادية وسياسية. وكان للإمبريالية الروسية في ذلك الوقت تأثير مباشر على الدولة العثمانية. كان الخطاب السياسي يهيمن عليه المشكلات الاقتصادية والانتفاضات الوطنية. حاولت الدولة العثمانية اللحاق بالعالم الغربي بتمرير الاصلاحات السياسية والادارية. جاءت فترة الاضمحلال في أعقاب انحلال الدولة العثمانية (1908–1922).

خلفية

مع أن العالم الإسلامي كان قد فقد سطوته الحربية منذ رد سوبييسكي الترك عن فيينا عام 1683، إلا أنه ظل مسيطراً على المغرب والجزائر وتونس وليبيا ومصر وشبه جزيرة العرب وفلسطين وسوريا وفارس وآسيا الصغرى والقرم وجنوبي روسيا وبسارابيا ومولداڤيا وولاخيا (رومانيا) وبلغاريا والصرب (يوغسلافيا) والجبل الأسود والبوسنة ودلماشيا واليونان وكريت وجزر الأرخبيل وتركيا. وهذه الأقطار كلها- باستثناء فارس- كانت جزءاً من إمبراطورية الأتراك العثمانيين المترامية الأطراف. فعلى الساحل الدلماشي بلغوا الأدرياتيك وواجهوا الولايات البابوية، وعلى البوسفور تسلطوا على المنفذ البحري الوحيد من البحر الأسود، وكان في مقدورهم أن يقفوا سداً منيعاً بين الروس والبحر المتوسط متى شاءوا.

فإذا عبرنا الأقاليم المجرية إلى بلاد المسلمين لم نلحظ للوهلة الأولى فرقاً يذكر بين المدينتين المسيحية والإسلامية. فهنا أيضاً كان فقراء المسلمين السذج الأتقياء يفلحون الأرض تحت إمرة سادتهم الأغنياء والأذكياء المتشككين. ولكن المشهد الاقتصادي يتغير فيما وراء البوسفور: فلا يكاد المزروع من الأقاليم يبلغ 15%، أما الباقي فصحراء أو جبال لا تتيح غير التعدين أو الرعي، هناك كان الإنسان يتميز به الإقليم هو البدوي الذي أسود لونه وتحمص جلده من الشمس، وتدثر على نحو معقد اتقاء للرمال والقيظ. أما المدن الساحلية والمتفرقة هنا وهناك كانت حافلة بالتجارة والحرف اليدوية، ولكن الحياة بدت أكثر دعة واسترخاء مما كانت في المراكز المسيحية، فالنساء يلزمن بيوتهن أو يسرن في وقار شديد تحت أحمالهن ووراء خمرهن، والرجال يمشون الهوينا في الشوارع. وكان جل الصناعة يدوياً، وورشة الصانع ملحقاً يتصدر بيته، وكان يدخن غليونه ويتجاذب الحديث مع غيره أثناء العمل، وأحيناً يشارك زبوناً قهوته.

ويمكن القول بوجه عام أن التركي العادي كان قانعاً غاية القناعة بمدينته، حتى لقد ظل قروناً لا يطيق أي تغيير ذي بال. وكانت التقاليد هنا كما كانت في التعاليم الكاثوليكية مقدسة قداسة التنزيل. أما الدين فكان أعظم قوة وانتشاراً في الأقطار الإسلامية مما كان في العالم المسيحي، والقرآن هو الشريعة والديانة معاً، وفقهاء الإسلام شراح الشريعة الرسميون. وكان الحج إلى مكة المكرمة يقود كل عام درامته المثيرة فوق رمال الصحراء وعلى الطرق المتربة. أما في الطبقات العليا فإن البدع العقلانية التي طلع بها معتزلة القرن الثامن الميلادي، والتي واصلها الشعراء والفلاسفة المسلمون طوال عصر الإيمان، لقيت قبولاً واسعاً مستوراً. كتبت الليدي ماري ورتلي مونتاجيو من الآستانة في 1719 تقول:

"إن الأفندية (أي الطبقة المتعلمة).. ليسوا أكثر إيماناً بالوحي الذي أنزل على محمد (صلى الله عليه وسلم) منهم بعصمة البابا. ويصرحون بالربوبية بينهم وبين من يثقون بهم ولا يتكلمون على شريعتهم (أي ما يمليه القرآن الكريم) إلا بوصفها مؤسسة سياسية، تصلح الآن لأن يتقيد بها العقلاء من الناس وإن كانت أصلاً من عمل رجال السياسة والمتحمسين من رجال الدين."

وانقسم الإسلام بين مذهبي السنة والشيعة كما انقسمت مسيحية الغرب بين الكاثوليكية والبروتستانتية، ثم قام مذهب جديد في القرن الثامن عشر على يد محمد بن عبد الوهاب، أحد شيوخ نجد- وهو الهضبة الوسطى في ما نعرفها اليوم بالعربية السعودية. وكان الوهابيون من الإسلام أشبه بالبيورتان من المسيحية: استنكروا التعبد للأولياء، وهدموا أضرحة المشايخ والشهداء، واستهجنوا لبس الحرير والتدخين، ودافعوا عن حق كل فرد في أن يفسر القرآن لنفسه. وقد شاعت الخرافات في جميع المذاهب على السواء، ولقى دجاجلة الدين كما لقيت المعجزات الكاذبة التصديق السريع، وكان جل المسلمين يعدون مملكة السحر عالماً حقيقياً كعالم الرمال والشمس الذي يكتنفهم.[1]

أما التعليم فهيمن عليه رجال الدين الذين آمنوا بأن أضمن سبيل لتكوين المواطنين الصالحين أو الأتباع الأوفياء القبيلة هي ترويض الخلق لا تحرير الفكر. وكان رجال الدين قد انتصروا في معركتهم مع العلماء والفلاسفة والمؤرخين الذين ازدهروا أيام الإسلام الوسيط، فانتكس الفلك إلى التنجيم، والكيمياء إلى الخيمياء، والطب إلى السحر، والتاريخ إلى الأساطير. ولكن في كثير من المسلمين حلت المحكمة الصامتة محل التعليم والتفقه في المعرفة. وكما قال داوتي الحكيم البليغ:

"إن العرب والترك، الذين كتبهم هي وجوه الرجال... والذين شروحهم وتفاسيرهم هي الأقوال المأثورة السائرة ومئات الأمثال الحكيمة القديمة السائدة في عالم الشرق، هؤلاء قريبون من إدراك الحقائق الإنسانية. إنهم شيوخ راسخون في الحكمة وهم لا يزالون شباباً، ولا ينسون بعد ذلك إلا القليل مما تعلموا."

وقد أكد ورتلي مونتاجيو في خطاب كتبه عام 1717 لأديسون أن "الرجال ذوي الشأن من الأتراك يبدون في أحاديثهم مهذبين لا يقلون تحضراً عن أي رجال التقيت بهم في إيطاليا"، أجل فالحكمة ليس لها وطن.

الاضمحلال

على عرش هذه الدولة العثمانية، من الفرات إلى الأطلنطي، تربع سلاطين عصر الاضمحلال. ولقد نظرنا في موقع آخر من هذا الكتاب) في أسباب ذلك الاضمحلال: وهي انتقال تجارة غربي أوربا التي تقصد آسيا، إذ أصبحت تدور حول أفريقيا بحراً بدلاً من طريقها البري الذي كان يختر مصر أو غربي آسيا؛ وتخريب قنوات الري أو إهمالها؛ وتوسع الإمبراطورية وامتدادها إلى مسافات مترامية لا تتيح لها الحكم المركزي الفعال وما ترتب على ذلك من استقلال الباشوات ونزوع الولايات إلى الانفصال؛ وتدهورت الحكومة المركزية لتفشي الرشوة والعجز والكسل، وتمرد الانكشارية المرة تلو المرة على النظام الصارم الذي كان له الفضل فيما بلغوا من قسوة وتسلط القدرية والجمود على الحياة والفكر، وتراخي السلاطين الذين استطابوا خدور النساء وآثروها على ساحات الوغى.

وقد استهل أحمد الثالث حكمه بسماحه للإنكشارية بأن يملوا عليه اختياره لكبير وزرائه (الصدر الأعظم). وهذا الوزير هو الذي قبل رشوة بلغت 230.000 روبل بعد أن قاد 200.000 تركي ضد 38.000 جندي من جيش بطرس الأكبر عند نهر بروت، لقاء سماحه للقيصر المحاصر بالفرار (21 يوليو 1711). وحدث أن ألـّبت البندقية أهل الجبل الأسود للثورة على تركيا، فأعلنت هذه الحرب عليها (1715) وأتمت فتح كريت واليونان. فلما أن تدخلت النمسا، أعلنت تركيا الحرب عليها (1716)، ولكن أوجين أمير سافوا هزم الترك في بترفارداين وأكره السلطان بمقتضى معاهدة بساروفتز (1718) على الجلاء من المجر، والنزول عن بلغراد وأجزاء من ولاشيا للنمسا، وتسليم البندقية حصوناً في ألمانيا ودلماشيا. ولم تسفر المحاولات التي بذلتها تركيا لتعويض هذه الخسائر بالغارات تشنها على فارس إلا على المزيد من النكسات والهزائم، وقد قتل الغوغاء- بقيادة عامل حمام- الوزير إبراهيم باشا وأكرهوا أحم على التنازل عن العرش (1730).

وجدد ابن أخيه محمود الأول (1730- 54) الصراع مع الغرب ليفرض بالحرب تدفق الضرائب وتعاليم الدين، وانتزع جيش تركي أوخاكوف وكلبورون من الروسيا، واسترد جيش آخر بلغراد من النمسا. غير أن اضمحلال تركيا عاود سيرته الأولى في عهد مصطفى الثالث (1757- 74). ففي 1762 أعلنت بلغاريا استقلالها. وفي 1769 خاضت تركيا الحرب مع الروسيا منعاً لانتشار سلطان الروسيا في بولندا. وهكذا بدأ ذلك الصراع الطويل الذي أنزلت فيه جيوش كاترين الكبرى هزائم ساحقة بالأتراك. فلما مات مصطفى أبرم أخوه عبد الحميد الأول (1774- 89) معاهدة مذلة تسمى قجوق قينارجي (1774)، قضت على النفوذ التركي في بولندا وجنوبي الروسيا ومالدافيا وولاشيا، وعلى هيمنة الأتراك على البحر الأسود. وجدد عبد الحميد الحرب في 1787، فهزم هزائم منكرة، ومات كمداً. وكان على تركيا أن تنتظر حتى يجيء كمال باشا (أتاتورك) لينهي قرنين من الفوضى ويجعل منها دولة حديثة.

التحديث (1808 - 1839)

محمود الثاني (1808-1839)

بعدما تولى محمود الثاني الحكم كان عليه التعامل مع قضايا متعددة. واستمرت الغيوم التي خيمت على عهده لأجيال متعاقبة. المسألة الشرقية مع روسيا، إنگلترة، وفرنسا. ظهرت المشكلات العسكرية من الإنكشارية المتمردين، العلماء المتشديين. كما وقعت عدة تمردات بين الوهابيين، المماليك، الصرب، الألبان، اليونانيين، الدروز، الأكراد، السوريين، والمصريين. وكان لديه أيضاً مشكلات ادارية سببها الباشوات المتمردين، الذين طمحوا في تأسيس ممالك جدية على أطلال آل عثمان.

Mahmud understood the growing problems of the state and the approaching overthrow of the monarchy and began to deal with the problems as he saw them. For example, he closed the Court of Confiscations, and took away much of the power of the pashas. He personally set an example of reform by regularly attending the Divan, or state council. The practice of the sultan's avoiding the Divan had been introduced two centuries prior, during the reign of Suleiman I, and was considered to be one of the causes of the decline of the Empire. Mahmud II also addressed some of the worst abuses connected with the Vakifs, by placing their revenues under state administration. However, he did not venture to apply this vast mass of property to the general purposes of the government.

الصرب، ع1810

In 1804 the Serbian Revolution against Ottoman rule erupted in the Balkans, running in parallel with the Napoleonic invasion. By 1817, when the revolution ended, Serbia was raised to the status of self-governing monarchy under nominal Ottoman suzerainty.[2] In 1821 the First Hellenic Republic became the first Balkan country to achieve its independence from the Ottoman Empire. It was officially recognised by the Porte in 1829, after the end of the Greek War of Independence.

اليونان، ع1820

In 1814, a secret organization called the Filiki Eteria was founded with the aim of liberating Greece. The Filiki Eteria planned to launch revolts in the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities, and capital with its surrounding areas. The first of these revolts began on 6 March 1821 in the Danubian Principalities which was put down by the Ottomans. On 17 March 1821, the Maniots declared war which was the start of revolutionary actions from other controlled states. In October 1821, Theodoros Kolokotronis had captured Tripolitsa, followed by other revolts in Crete, Macedonia, and Central Greece. Tensions soon developed among different Greek factions, leading to two consecutive civil wars. Mehmet Ali of Egypt agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gain. By the end of 1825, most of the Peloponnese was under Egyptian control, and the city of Missolonghi was put under siege and fell in April 1826. Ibrahim had succeeded in suppressing most of the revolt in the Peloponnese and Athens had been retaken. Russia, Britain and France decided to intervene in the conflict and each nation sent a navy to Greece. Following news that combined Ottoman–Egyptian fleets were going to attack the Greek island of Hydra, the allied fleet intercepted the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet in the battle of Navarino. Following a week long standoff, a battle began which resulted in the destruction of the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet. With the help of a French expeditionary force proceeded to the captured part of Central Greece by 1828.

The Greek War of Independence saw the beginning of the spread of the Western notion of nationalism, stimulated the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire, and eventually caused the breakdown of the Ottoman millet concept. Unquestionably, the concept of nationhood prevalent in the Ottoman Empire was different from the current one as it was centered on religion.

الواقعة الخيرية 1826

Mahmud II's most notable achievements include the إلغاء الإنكشارية in 1826, the establishment of a modern Ottoman army, and the preparation of the Tanzimat reforms in 1839. By 1826, the sultan was ready to move against the Janissary in favor of a more modern military. Mahmud II incited them to revolt on purpose, describing it as the sultan's "coup against the Janissaries". The sultan informed them, through a fatwa, that he was forming a new army, organised and trained along modern European lines. As predicted, they mutinied, advancing on the sultan's palace. In the ensuing fight, the Janissary barracks were set in flames by artillery fire resulting in 4,000 Janissary fatalities. The survivors were either exiled or executed, and their possessions were confiscated by the Sultan. This event is now called الواقعة الخيرية. The last of the Janissaries were then put to death by decapitation in what was later called the blood tower، في سالونيك.[3]

These marked the beginning of the modernization and had immediate effects such as introducing European-style clothing, architecture, legislation, institutional organization, and land reform.

روسيا، 1828–1829

The Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 did not give him time to organize a new army, and the Sultan was forced to use these young and undisciplined recruits in the fight against the veterans of the Tsar. The war was brought to a close by the disastrous Treaty of Adrianople. While the reforms in question were mainly implemented to improve the military, the most notable development that arose out of these efforts was a series of schools teaching everything from math to medicine to train new officers.

مصر، عقد 1830

Later in his reign, Mahmud became involved in disputes with the Wāli of Egypt and Sudan, Muhammad Ali, who was technically Mahmud's vassal. The Sultan had asked for Muhammad Ali's help in suppressing a rebellion in Greece, but had not paid the promised price for his services. In 1831, Muhammad Ali declared war and managed to take control of Syria and Arabia by the war's end in 1833. In 1839, Mahmud resumed the war, hoping to recover his losses, but he died at the time news was on its way to Constantinople that the Empire's army had been defeated at Nezib by an Egyptian army led by Muhammad Ali's son, Ibrahim Pasha.

الاقتصاد

In his time the financial situation of the Empire was dire, and certain social classes had long been oppressed by burdensome taxes. In dealing with the complicated questions that arose, Mahmud II is considered to have demonstrated the best spirit of the best of the Köprülüs. A Firman of 22 February 1834 abolished the vexatious charges which public functionaries, when traversing the provinces, had long been accustomed to take from the inhabitants. By the same edict all collection of money, except for the two regular half-yearly periods, was denounced as an abuse. "No one is ignorant," said Sultan Mahmud II in this document, "that I am bound to afford support to all my subjects against vexatious proceedings; to endeavour unceasingly to lighten, instead of increasing their burdens, and to ensure peace and tranquility. Therefore, those acts of oppression are at once contrary to the will of God, and to my imperial orders."

The haraç, or capitation tax, though moderate and exempting those who paid it from military service, had long been made an engine of gross tyranny through the insolence and misconduct of government collectors. The Firman of 1834 abolished the old mode of levying it, and ordained that it should be raised by a commission composed of the Kadı, the Muslim governors, and the Ayans, or municipal chiefs of Rayas in each district. Many other financial improvements were effected. By another important series of measures, the administrative government was simplified and strengthened, and a large number of sinecure offices were abolished. Sultan Mahmud II gave a valuable personal example of good sense and economy, organised the imperial household, suppressed all titles without duties, and eliminated all the positions of salaried officials without functions.

فترة التنظيمات 1839-1876

In 1839, the Hatt-i Sharif proclamation launched the Tanzimat (from Arabic: تنظيم tanẓīm, meaning "organisation") (1839–76), period. Previous to the first of the firmans, the property of all persons banished or condemned to death was forfeited to the crown, which kept a sordid motive for acts of cruelty in perpetual operation, besides encouraging a host of vile Delators. The second firman removed the ancient rights of Turkish governors to condemn men to instant death at will; the Paşas, the Ağas, and other officers were enjoined that "they should not presume to inflict, themselves, the punishment of death on any man, whether Raya or Turk, unless authorized by a legal sentence pronounced by the Kadi, and regularly signed by the judge."

The Tanzimat reforms did not halt the rise of nationalism in the Danubian Principalities and the Principality of Serbia, which had been semi-independent for almost six decades. In 1875, the tributary principalities of Serbia and Montenegro, and the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, unilaterally declared their independence from the empire. Following the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), the empire granted independence to all three belligerent nations. Bulgaria also achieved virtual independence[بحاجة لمصدر] (as the Principality of Bulgaria); its volunteers had participated in the Russo-Turkish War on the side of the rebelling nations.

The government's series of constitutional reforms led to a fairly modern conscripted army, banking system reforms, the decriminalization of homosexuality, the replacement of religious law with secular law[4] and guilds with modern factories.

عبد المجيد الأول 1839-1876

ع1840

The Ottoman Ministry of Post was established in Istanbul on 23 October 1840.[5][6] The first post office was the Postahane-i Amire near the courtyard of the Yeni Mosque.[5]

The introduction of the first Ottoman paper banknotes (1840) and opening of the first post offices (1840); the reorganization of the finance system according to the French model (1840); the reorganization of the Civil and Criminal Code according to the French model (1840); the establishment of the Meclis-i Maarif-i Umumiye (1841) which was the prototype of the First Ottoman Parliament (1876); the reorganisation of the army and a regular method of recruiting, levying the army and fixing the duration of military service (1843–44); the adoption of an Ottoman national anthem and Ottoman national flag (1844); the institution of a Council of Public Instruction (1845) and the Ministry of Education (Mekatib-i Umumiye Nezareti, 1847, which later became the Maarif Nezareti, 1857); the abolition of slavery and slave trade (1847); the establishment of the first modern universities (darülfünun, 1848), academies (1848) and teacher schools (darülmuallimin, 1848).

The Ottoman Ministry of Post was established in Istanbul on 23 October 1840.[5][6] The first post office was the Postahane-i Amire near the courtyard of the Yeni Mosque.[5]

Samuel Morse received his first ever patent for the telegraph in 1847, at the old Beylerbeyi Palace (the present Beylerbeyi Palace was built in 1861–1865 on the same location) in Istanbul, which was issued by Sultan Abdülmecid who personally tested the new invention.[7] Following this successful test, installation works of the first telegraph line (Istanbul-Adrianople–Şumnu)[8] began on 9 August 1847.[9]

بطاقة الهوية والتعداد العثماني 1844

While the Ottoman Empire had population records prior to the 1830s, it was only in 1831 that the Office of Population Registers fund (Ceride-i Nüfus Nezareti) was founded. The Office decentralized in 1839 to draw more accurate data. Registrars, inspectors, and population officials were appointed to the provinces and smaller administrative districts. They recorded births and deaths periodically and compared lists indicating the population in each district. These records were not a total count of the population. Rather, they were based on what is known as “head of household”. Only the ages, occupation, and property of the male family members only were counted.

The first nationwide Ottoman census was in 1844. The first national identity cards which officially named the Mecidiye identity papers, or informally kafa kağıdı (head paper) documents.

ع1850

In 1856, the Hatt-ı Hümayun promised equality for all Ottoman citizens regardless of their ethnicity and religious confession; which thus widened the scope of the 1839 Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane. Overall, the Tanzimat reforms had far-reaching effects. Those educated in the schools established during the Tanzimat period included Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and other progressive leaders and thinkers of the Republic of Turkey and of many other former Ottoman states in the Balkans, the Middle East and North Africa. These reforms included[10] guarantees to ensure the Ottoman subjects perfect security for their lives, honour and property;

Establishment of the Ministry of Healthcare (Tıbbiye Nezareti, 1850); the Commerce and Trade Code (1850); establishment of the Academy of Sciences (Encümen-i Daniş, 1851); establishment of the Şirket-i Hayriye which operated the first steam-powered commuter ferries (1851); the first European style courts (Meclis-i Ahkam-ı Adliye, 1853) and supreme judiciary council (Meclis-i Ali-yi Tanzimat, 1853); establishment of the modern Municipality of Istanbul (Şehremaneti, 1854) and the City Planning Council (İntizam-ı Şehir Komisyonu, 1855); the abolition of the capitation (Jizya) tax on non-Muslims, with a regular method of establishing and collecting taxes (1856); non-Muslims were allowed to become soldiers (1856); various provisions for the better administration of the public service and advancement of commerce; the establishment of the first telegraph networks (1847–1855) and railways (1856); the replacement of guilds with factories; the establishment of the Ottoman Central Bank (originally established as the Bank-ı Osmanî in 1856, and later reorganised as the Bank-ı Osmanî-i Şahane in 1863)[11] and the Ottoman Stock Exchange (Dersaadet Tahvilat Borsası, established in 1866);[12] the Land Code (Arazi Kanunnamesi, 1857); permission for private sector publishers and printing firms with the Serbesti-i Kürşad Nizamnamesi (1857); establishment of the School of Economical and Political Sciences (Mekteb-i Mülkiye, 1859).

In 1855 the Ottoman telegraph network became operational and the Telegraph Administration was established.[5][6][8]

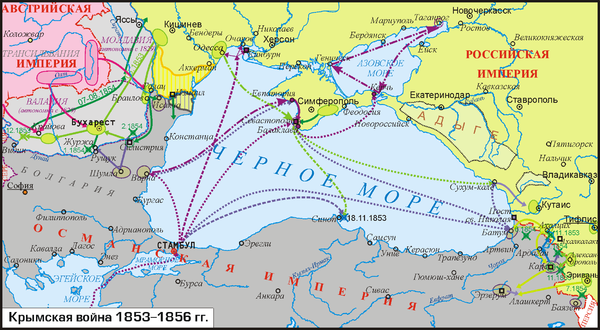

حرب القرم 1853–1856

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining Ottoman Empire. Britain and France successfully defended the Ottoman Empire against Russia.[13]

Most of the fighting took place when the allies landed on Russia's Crimean Peninsula to gain control of the Black Sea. There were smaller campaigns in western Anatolia, the Caucasus, the Baltic Sea, the Pacific Ocean and the White Sea. It was one of the first "modern" wars, as it introduced new technologies to warfare, such as the first tactical use of railways and the telegraph.[14] The subsequent Treaty of Paris (1856) secured Ottoman control over the Balkan Peninsula and the Black Sea basin. That lasted until defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

The Ottoman Empire took its first foreign loans on 4 August 1854,[15] shortly after the beginning of the Crimean War.[16]

The war caused an exodus of the Crimean Tatars. From the total Tatar population of 300,000 in the Tauride Province, about 200,000 Crimean Tatars moved to the Ottoman Empire in continuing waves of emigration.[17] Toward the end of the Caucasian Wars, 90% of the Circassians were exiled from their homelands in the Caucasus and settled in the Ottoman Empire.[18] During the 19th century, there was an exodus to present-day Turkey by a large portion of Muslim peoples from the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea and Crete, By the early 19th century, as many as 45% of the islanders may have been Muslim, had great influence in molding the country's fundamental features. These people were called Muhacir under a general definition.[19] By the time the Ottoman Empire came to an end in 1922, half of the urban population of Turkey was descended from Muslim refugees from Russia.[20] Crimean Tatar refugees in the late 19th century played an especially notable role in seeking to modernise Turkish education.[20]

الأرمن، ع1860

Influenced by the Age of Enlightenment and the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire, the Armenian national liberation movement developed in the early 1860s. The factors contributing to its emergence made the movement similar to that of the Balkan nations, especially the Greeks. The Armenian élite and various militant groups sought to improve and defend the mostly rural Armenian population of the eastern Ottoman Empire from the Muslims, but the ultimate goal was the creation of an Armenian state in the Armenian-populated areas controlled at the time by the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire.

عبد العزيز 1861–1876

Abdülaziz continued the Tanzimat and Islahat reforms. New administrative districts (vilayets) were set up in 1864 and a Council of State was established in 1868. Public education was organized on the French model and Istanbul University was reorganized as a modern institution in 1861. Abdülaziz was also the first sultan who traveled outside his empire. His 1867 trip included a visit to the United Kingdom. The Press and Journalism Regulation Code (Matbuat Nizamnamesi, 1864); among others.[10] 1876 the first international mailing network between Istanbul and the lands beyond the vast Ottoman Empire was established.[5] In 1901 the first money transfers were made through the post offices and the first cargo services became operational.[5] In 1868 homosexuality was decriminalised[21]

The Christian millets gained privileges, such as in the Armenian National Constitution of 1863. This Divan-approved form of the Code of Regulations consisted of 150 articles drafted by the Armenian intelligentsia. Another institution was the newly formed Armenian National Assembly.[22] The Christian population of the empire, owing to their higher educational levels, started to pull ahead of the Muslim majority, leading to much resentment on the part of the latter.[20] In 1861, there were 571 primary and 94 secondary schools for Ottoman Christians with 140,000 pupils in total, a figure that vastly exceeded the number of Muslim children in school at the same time, who were further hindered by the amount of time spent learning Arabic and Islamic theology.[20] In turn, the higher educational levels of the Christians allowed them to play a large role in the economy.[20] In 1911, of the 654 wholesale companies in Istanbul, 528 were owned by ethnic Greeks.[20]

In 1871 the Ministry of Post and the Telegraph Administration were merged, becoming the Ministry of Post and Telegraph.[6] In July 1881 the first telephone circuit in Istanbul was established between the Ministry of Post and Telegraph in the Soğukçeşme quarter and the Postahane-i Amire in the Yenicami quarter.[9] On 23 May 1909, the first manual telephone exchange with a 50 line capacity entered service in the Büyük Postane (Grand Post Office) in Sirkeci.[9]

بلغاريا، ع1870

The rise of national awakening of Bulgaria led to the Bulgarian revival movement. Unlike Greece and Serbia, the nationalist movement in Bulgaria did not concentrate initially on armed resistance against the Ottoman Empire. After the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate on 28 February 1870 a large-scale armed struggle started to develop as late as the beginning of the 1870s with the establishment of the Internal Revolutionary Organisation and the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, as well as the active involvement of Vasil Levski in both organisations. The struggle reached its peak with the April Uprising of 1876 in several Bulgarian districts in Moesia, Thrace, and Macedonia. The suppression of the uprising and the atrocities committed by Ottoman soldiers against the civilian population increased the Bulgarian desire for independence.

الألبان، ع1870

Because of religious ties of the Albanian majority of the population with the ruling Ottomans and the lack of an Albanian state in past, nationalism was less developed among Albanians in the 19th century than among other southeast European nations. Only from the 1870s and onwards did a movement of ‘national awakening‘ evolve among them - greatly delayed, compared to the Greeks and the Serbs. The 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War dealt a decisive blow to Ottoman power in the Balkan Peninsula. The Albanians' fear that the lands they inhabited would be partitioned among Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece fueled the rise of Albanian nationalism.

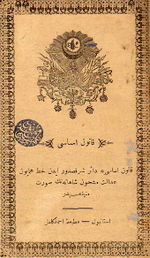

الدستور العثماني 1876

The reformist period peaked with the Constitution, called the Kanûn-u Esâsî (meaning "Basic Law" in Ottoman Turkish), written by members of the Young Ottomans, which was promulgated on 23 November 1876. It established the freedom of belief and equality of all citizens before the law. The empire's First Constitutional era, was short-lived. But the idea of Ottomanism proved influential. A group of reformers known as the Young Ottomans, primarily educated in Western universities, believed that a constitutional monarchy would give an answer to the empire's growing social unrest. Through a military coup in 1876, they forced Sultan Abdülaziz (1861–1876) to abdicate in favour of Murad V. However, Murad V was mentally ill and was deposed within a few months. His heir-apparent, Abdülhamid II (1876–1909), was invited to assume power on the condition that he would declare a constitutional monarchy, which he did on 23 November 1876. The parliament survived for only two years before the sultan suspended it. When forced to reconvene it, he abolished the representative body instead. This ended the effectiveness of the Kanûn-ı Esâsî.

مراد الخامس 1876

After Abdülaziz's dethronement, Murat was enthroned. It was hoped that he would sign the constitution. However, due to health problems, Murat was also dethroned after 93 days; he was the shortest reigning sultan of the Empire.

الفترة المشروطية الأولى 1876–1878

الفترة المشروطية الأولى في الدولة العثمانية كانت فترة ملكية دستورية منذ إصدار القانون الأساسي، الذي صاغه أعضاء جمعية تركيا الفتاة، في 23 نوفمبر 1876 حتى 13 فبراير 1878. انتهت الفترة بتعليق البرلمان العثماني (المبعوثان) بقرار من عبد الحميد الثاني.

عبد الحميد الثاني 1876–1879

الحرب التركية الروسية 1877–1878

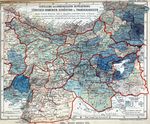

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 had its origins in a rise in nationalism in the Balkans as well as in the Russian goal of recovering territorial losses it had suffered during the Crimean War, reestablishing itself in the Black Sea and following the political movement attempting to free Balkan nations from the Ottoman Empire. As a result of the war, the principalities of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, each of which had de facto sovereignty for some time, formally proclaimed independence from the Ottoman Empire. After almost half a millennium of Ottoman rule (1396–1878), the Bulgarian state was reestablished as the Principality of Bulgaria, covering the land between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains (except Northern Dobrudja which was given to Romania) and the region of Sofia, which became the new state's capital. The Congress of Berlin also allowed Austria-Hungary to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina and Great Britain to take over Cyprus, while the Russian Empire annexed Southern Bessarabia and the Kars region.

مؤتمر برلين 1878

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a meeting of the leading statesmen of Europe's Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire. In the wake of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) that ended with a decisive victory for Russia and her Orthodox Christian allies (subjects of the Ottoman Empire before the war) in the Balkan Peninsula, the urgent need was to stabilise and reorganise the Balkans, and set up new nations. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who led the Congress, undertook to adjust boundaries to minimise the risks of major war, while recognising the reduced power of the Ottomans, and balance the distinct interests of the great powers.

As a result, Ottoman holdings in Europe declined sharply; Bulgaria was established as an independent principality inside the Ottoman Empire, but was not allowed to keep all its previous territory. Bulgaria lost Eastern Rumelia, which was restored to the Turks under a special administration; and Macedonia, which was returned outright to the Turks, who promised reform. Romania achieved full independence, but had to turn over part of Bessarabia to Russia. Serbia and Montenegro finally gained complete independence, but with smaller territories.

In 1878, Austria-Hungary unilaterally occupied the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Novi Pazar, but the Ottoman government contested this move and maintained its troops in both provinces. The stalemate lasted for 30 years (Austrian and Ottoman forces coexisted in Bosnia and Novi Pazar for three decades) until 1908, when the Austrians took advantage of the political turmoil in the Ottoman Empire that stemmed from the Young Turk Revolution and annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina, but pulled their troops out of Novi Pazar in order to reach a compromise and avoid a war with the Turks.

In return for British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli's advocacy for restoring the Ottoman territories on the Balkan Peninsula during the Congress of Berlin, Britain assumed the administration of Cyprus in 1878[23] and later sent troops to Egypt in 1882 with the pretext of helping the Ottoman government to put down the Urabi Revolt; effectively gaining control in both territories (Britain formally annexed the still nominally Ottoman territories of Cyprus and Egypt on 5 November 1914, in response to the Ottoman Empire's decision to enter World War I on the side of the Central Powers.) France, on its part, occupied Tunisia in 1881.

The results were first hailed as a great achievement in peacemaking and stabilisation. However, most of the participants were not fully satisfied, and grievances regarding the results festered until they exploded into world war in 1914. Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece made gains, but far less than they thought they deserved. The Ottoman Empire called at the time the "sick man of Europe", was humiliated and significantly weakened, rendering it more liable to domestic unrest and more vulnerable to attack. Although Russia had been victorious in the war that occasioned the conference, it was humiliated at Berlin, and resented its treatment. Austria gained a great deal of territory, which angered the South Slavs, and led to decades of tensions in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bismarck became the target of hatred of Russian nationalists and Pan-Slavists, and found that he had tied Germany too closely to Austria in the Balkans.[24]

In the long-run, tensions between Russia and Austria-Hungary intensified, as did the nationality question in the Balkans. The Congress succeeded in keeping Istanbul in Ottoman hands. It effectively disavowed Russia's victory. The Congress of Berlin returned to the Ottoman Empire territories that the previous treaty had given to the Principality of Bulgaria, most notably Macedonia, thus setting up a strong revanchist demand in Bulgaria that in 1912 led to the First Balkan War in which the Turks were defeated and lost nearly all of Europe. As the Ottoman Empire gradually shrank in size, military power and wealth, many Balkan Muslims migrated to the empire's remaining territory in Balkans or to the heartland in Anatolia.[25][26] Muslims had been the majority in some parts of Ottoman Empire such as the Crimea, the Balkans and the Caucasus as well as a plurality in southern Russia and also in some parts of Romania. Most of these lands were lost with time by the Ottoman Empire between 19th and 20th centuries. By 1923, only Anatolia and eastern Thrace remained as the Muslim land.[27]

الاستبداد 1879-1908

عبد الحميد الثاني 1879–1908

Abdul Hamid is also considered one of the last sultans to have full control. His reign struggled with the culmination of 75 years of change throughout the empire and an opposing reaction to that change.[20] He was particularly concerned with the centralization of the empire.[28] His efforts to centralize the Sublime Porte were not unheard of among other sultans. The Ottoman Empire’s local provinces had more control over their areas than the central government. Abdul Hamid II's foreign relations came from a “policy of non-commitment."[29] The sultan understood the fragility of the Ottoman military, and the Empire’s weaknesses of its domestic control.[29] Pan-Islamism became Abdülhamid’s solution to the empire’s loss of identity and power.[30] His efforts to promote Pan-Islamism were for the most part unsuccessful because of the large non-Muslim population, and the European influence onto the empire.[28] His policies essentially isolated the Empire, which further aided in its decline. Several of the elite who sought a new constitution and reform for the empire were forced to flee to Europe.[28] New groups of radicals began to threaten the power of the Ottoman Empire.

مصر، عقد 1880

After gaining some amount of autonomy during the early 1800s, Egypt had entered into a period of political turmoil by the 1880s. In April 1882, British and French warships appeared in Alexandria to support the khedive and prevent the country from falling into the hands of anti-European nationals.

In August 1882 British forces invaded and occupied Egypt on the pretext of bringing order. The British supported Khedive Tewfiq and restored stability with was especially beneficial to British and French financial interests. Egypt and Sudan remained as Ottoman provinces de jure until 1914, when the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers of World War I. Great Britain officially annexed these two provinces and Cyprus in response.

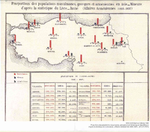

التعداد العثماني 1893–96

In 1867, the Council of States took charge of drawing population tables, increasing the precision of population records. They introduced new measures of recording population counts in 1874. This led to the establishment of a General Population Administration, attached to the Ministry of Interior in 1881-1882.

The first official census (1881–93) took 10 years to finish. In 1893, the results were compiled and presented. This census is the first modern, general and standardized census accomplished not for taxation nor for military purposes, but to acquire demographic data. The population was divided into ethno-religious and gender characteristics. Numbers of both male and female subjects are given in ethno-religious categories including Muslims, Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Catholics, Jews, Protestants, Latins, Syriacs and Gypsies[31][32]

الأرمن، ع1890

Although granted their own constitution and national assembly with the Tanzimat reforms, the Armenians attempted to demand implementation of Article 61 from the Ottoman government as agreed upon at the Congress of Berlin in 1878.[34]

المطالبون بالاستقلال الذاتي

During 1880 - 1881, while the Armenian national liberation movement was in its early stage; lack of outside support and inability to maintain a trained, organized Kurdish force diminished Kurdish aspirations. However, two prominent Kurdish families (tribes) mounted opposition to the empire, based more from an ethno-nationalistic stand point. The Badr Khans were successionists while the Sayyids of Nihiri were autonomists. The Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 was followed in 1880 - 1881 by the attempt of Shaykh Ubayd Allah of Nihri to found an "independent Kurd principality" around Ottoman-Persian border (including the Van Vilayet) where Armenian population was significant. Shaykh Ubayd Allah of Nihri gathered 20,000 fighters.[35] Lacking discipline, his man left the ranks after pillaging and acquiring riches from the villages in the region (indiscriminately, including Armenian villages). Shaykh Ubayd Allah of Nihri captured by the Ottoman forces in 1882 and this movement ended.[35]

The Bashkaleh clash was the bloody encounter between the Armenakan Party and the Ottoman Empire in May 1889. Its name comes from Başkale, a border town of Van Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. The event was important, as it was reflected on main Armenian newspapers as the recovered documents on the Armenakans showed an extensive plot for a national movement.[36] Ottoman officials believed that the men were members of a large revolutionary apparatus and the discussion was reflected on newspapers, (Eastern Express, Oriental Advertiser, Saadet, and Tarik) and the responses were on the Armenian papers. In some Armenian circles, this event was considered as a martyrdom and brought other armed conflicts.[37] The Bashkaleh Resistance was on the Persian border, which the Armenakans were in communication with Armenians in the Persian Empire. The Gugunian Expedition, which followed within the couple months, was an attempt by a small group of Armenian nationalists from the Russian Armenia to launch an armed expedition across the border into the Ottoman Empire in 1890 in support of local Armenians.

The Kum Kapu demonstration occurred at the Armenian quarter of Kum Kapu, the seat of the Armenian Patriarch, was spared through the prompt action of the commandant, Hassan Aga.[38] On 27 July 1890, Harutiun Jangülian, Mihran Damadian and Hambartsum Boyajian interrupted the Armenian mass to read a manifesto and denounce the indifference of the Armenian patriarch and Armenian National Assembly. Harutiun Jangülian (member from Van) tried to assassinate the Patriarch of Istanbul. The goal was to persuade the Armenian clerics to bring their policies into alignment with the national politics. They soon forced the patriarch to join the procession heading to the Yildiz Palace to demand implementation of Article 61 of the Treaty of Berlin. It is significant that this massacre, in which 6000 Armenians are said to have perished, was not the result of a general rising of the Muslim population.[38] The Softas took no part in it, and many Armenians found refuge in the Muslim sections of the city.[38]

برنامج الإصلاح

The Kurdish (force, rebels, bandits) sacked neighboring towns and villages with impunity.[39]

The central assumption of the Hamidiye system—Kurdish tribes (Kurdish chiefdoms cited among Armenian security concerns) could be brought under military discipline—proved to be "Utopian". The Persian Cossack Brigade later proved that it can function as independent unit, but Ottoman example, which was modeled after, never replaced the tribal loyalty to Ottoman Sultan or even to its establishing unit.

In 1892, first time a trained and organized Kurdish force encouraged by the Sultan Abdul Hamid II. There are several reasons advanced as to why the Hamidiye light cavalry was created. The establishment of the Hamidiye was in one part a response to the Russian threat, but scholars believe that the central reason was to suppress Armenian socialist/nationalist revolutionaries.[40] The Armenian revolutionaries posed a threat because they were seen as disruptive, and they could work with the Russians against the Ottoman Empire.[40] The Hamidiye corps or Hamidiye Light Cavalry Regiments were well-armed, irregular, majority Kurdish cavalry (minor amounts of other nationalities, such as Turcoman) formations that operated in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire.[41] They were intended to be modeled after the Caucasian Cossack Regiments (example Persian Cossack Brigade) and were firstly tasked to patrol the Russo-Ottoman frontier[42] and secondly, to reduce the potential of Kurdish-Armenian cooperation.[43] The Hamidiye Cavalry was in no way a cross-tribal force, despite their military appearance, organization, and potential.[44] Hamidiye quickly find out that they could only be tried through a military court martial[45] They became immune to civil administration. Realizing their immunity, they turned their tribes into “legalized robber brigades” as they steal grain, reap fields not of their possession, drive off herds, and openly steal from shopkeepers.[46] Some argue that the creation of the Hamidiye “further antagonized the Armenian population” and it worsened the very conflict they were created to prevent.[47]

Kurdish chieftain also taxed the population of the region in sustaining these units, which Armenian's perceived this Kurdish taxation as an exploitation. When Armenian spokesmen confronted the Kurdish chieftain (issue of double taxation), it brought about enmity between both populations. The Hamidiye cavalry harassed and assaulted Armenians.[48]

In 1908, after the overthrow of Sultan, the Hamidiye Cavalry was disbanded as an organized force, but as they were “tribal forces” before official recognition, they stayed as “tribal forces” after dismemberment. The Hamidiye Cavalry is described as a military disappointment and a failure because of its contribution to tribal feuds.[49]

الأرمن

A major role in the Hamidian massacres of 1894-96 has been often ascribed to the Hamidiye regiments, particularly during the bloody suppression of Sasun (1894). On July 25, 1897 the Khanasor Expedition was against the Kurdish Mazrik tribe (Muzuri Kurds) who owned a significant portion of this cavalry. The first notable battle in the Armenian resistance movement took place in Sassoun, where nationalist ideals were proliferated by Hunchak activists, such as Mihran Damadian, Hampartsoum Boyadjian, and Hrayr. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation also played a significant role in arming the people of the region. The Armenians of Sassoun confronted the Ottoman army and Kurdish irregulars at Sassoun, succumbing to superior numbers.[50] This was followed by Zeitun Rebellion (1895–1896), which between the years 1891 and 1895, Hunchak activists toured various regions of Cilicia and Zeitun to encourage resistance, and established new branches of the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party.

In this area, something resembling a civil war between Armenians and Muslims (involving Hamidiye (cavalry)) raged for months before being brought to an end through mediation by the Great Powers. However, instead of Armenian autonomy in these regions, Kurds (Kurdish tribal chiefs) retained much of their autonomy and power.[51] The Abdulhamid made little attempt to alter the traditional power structure of “segmented, agrarian Kurdish societies” – agha, shayk, and tribal chief.[51] Because of their geographical position at the southern and eastern fringe of the empire and mountainous topography, and limited transportation and communication system.[51] The state had little access to these provinces and were forced to make informal agreements with tribal chiefs, for instance the Ottoman qadi and mufti did not have jurisdiction over religious law which bolstered Kurdish authority and autonomy.[51]

The 1896 Ottoman Bank takeover was perpetrated by an Armenian group armed with pistols, grenades, dynamite and hand-held bombs against the Ottoman Bank in Istanbul. The seizure of the bank lasted 14 hours, resulting in the deaths of 10 of the Armenian men and Ottoman soldiers. The Ottoman reaction to takeover saw further massacres and pogroms of the several thousand Armenians living in Constantinople and Sultan Abdul Hamid II threatening to level the entire building itself. However, intervention on part of the European diplomats in the city managed to persuade the men to give, assigning safe passage to the survivors to France. Despite the level of violence, the incident had wrought, the takeover was reported positively in the European press, praising the men for their courage and the objectives they attempted to accomplish.[52]

الاقتصاد

Economically, the empire had difficulty in repaying the Ottoman public debt to European banks, which caused the establishment of the Council of Administration of the Ottoman Public Debt. By the end of the 19th century, the main reason the empire was not overrun by Western powers was their attempt to maintain a balance of power in the area. Both Austria and Russia wanted to increase their spheres of influence and territory at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, but were kept in check mostly by Britain, which feared Russian dominance in the Eastern Mediterranean.

معرض صور

الأعيان

ربما جاءت أكبر الأخطار التي تحدت الدولة العثمانية في ذلك الوقت من جانب الأعيان المسلمين في المقام الأول وليس من القوى الأوروبية أو من رعاياها المسيحيين الغاضبين. وبسبب الإضطرابات التي أحدثتها الحروب والغليان الداخلي في البلقان كان الناس في حاجة إلى من يحميهم. وأكثر من هذا ففي بعض الأماكن أصبح الأمراء المحليون زعماء شعبين لأنهم ظهروا بمظهر الذي يحول بين السكان وبين السلطة المركزية العثمانية التي اتسمكت آنذاك بالجشع غير المعقول. ولما عجزت الحكومة عن إخضاع هؤلاء الزعماء للإعتراف بهم وعينتهم في وظائف رسمية, بل لقد اضطر الباب العالي أمام ضغط الأزمات المدنية والعسكرية إلى استخدام القوات غير النظامية بل والعصابات المحلية حين ضعفت كفاءة الجيش النظامي, ومن هنا حصل الأمراء المحليون على وظائف عسكرية علياً. وأمام عجز الحكومة عن السيطرة على الأعيان بشكل مباشر وجدت أن أفضل وسيلة تأليب بعضهم على بعض حتى يحدث توازن في القوة. وتلك السياسة في أحسن الأحوال كانت لعبة خطرة ذلك أنه في المقابل كان أولئك الأعيان يقومون بمساندة القوى المعادية للحكومة مثل الإنكشارية المتمردة.

والحقيقة أن القيادات العثمانية ذاتها أدركت ضعفها العسكري, وكانوا منشغلين بتدهور قوة دولتهم قبل أن يدركها خصوم الدولة في الداخل والخارج.وبالتالي لم تعد المسألة هي الحاجة إلى الإصلاح التي كانت واضحة بقدر ما كانت البحث عن الطريق الذي ينبغي أن تسلكه الدولة لتحقيق الإصلاح. وكان البعض يرى أن مكمن الضعف في الإمبراطورية يعود إلى انحرافها عن الممارسات التقليدية, وأنه يجب استعادة الأوضاع السابقة. وعلى العكس من ذلك كان هناك تيار قوي رأى أصحابه وجوب أن تتخلى الدولة عن أساليب التقاليد القديمة في الحكم والأخذ بنظام الؤسسات الغربية.

لكن المحاولات الأولى للإصلاح أخفقت بسبب معارضة النبلاء المحليين رغبة منها في استغفلال كوارث الفترة لصالحهم. وكان السلطان سليم الثالث الذي اعتلى السلطنة في 1789 هو أول سلطان يتجه لللإصلاح فقد أتاحت له فترة من الهدوء والسلام خلال عام 1792 من أن يقترب من مسألة إعادة تنظيم الجيش الذي كان تدريبه يتم بمعرفة الفرنسيين وكانت الحكومة الفرنسية ما تزال راغبة في استمرار تقديم هذه المساعدة والواقع أن الفرق الإنكشارية كانت هي مظهر ضعف القوات العثمانية حيث أصبحت جناحاً سياسياً منظماً له نفوذ في الحياة السياسية ويمثل خطراً محتملاً في الشؤون الداخلية أكثر من كونها مجرد قوة عسكرية تقوم بدورها إزاء التهديدات الخارجية. وعلى هذا استهدف سليم من الإصلاح تطوين قوة مشاة جديدة موازية لكي تنافس الإنكشارية عرفت باسم "النظام الجديد" تلقى أفرادها تدريباً على الأسس الغبربية بما فيه إرتداء الزي العسكري. وقد شمل منهج الإصلاح عنده إرساء سياسات ضريبية وإدارية جديدة لكن الإصلاح العسكري كان أكثر أهمية.

ولكن من سوء حظ الدولة العثمانية أن سليم كان أضعف من أن يقوم بتنفيذ أفكاره الإصلاحية إذ لم يكن يملك تجهيزات مناسبة لما ينويه من إصلاحات، ولم تكن بجانبه مجموعة قوية من المؤيدين تتولى تنفيذ التغييرات المطلوبة التي تعارضها العناصر لها مصلحة في بقاء النظام القديم. وهكذا بقيت الإنكشارية تمثل خطراً سياسياً كبيراً يمكنها تهديد حكومة السلطان في الداخل وفي القوت نفسه تعجز عن هزيمة أعدائه في الخارج.

وأكثر من هذا ففي 1807 وقع صراع حاسم بين انصار السلطان سليم الثالث ومعارضيه من المحافظين الإنكشارية والأعيان, وكانت الدولة في حرب مع روسيا وفي الوقت نفسه وقع تمرد في بلاد الصرب كما سوف نرى وانتهى الأمر بوقوع انتفاضة عسكرية في مايو 1807 أطاحت بالسلطان واعتلى العرش محله مصطفى الرابع في يولية من العام نفسه الذي أبقى على خياة سليم, ونشأ نظام جديد هيمنت على أركانه عناصر من المحافظين ومن الإنكشارية المسلمون بطبيعة الحال. لكن ما لبث أنصار سليم ومؤيدو الإصلاح أن تجمعوا في في روزيه Ruse تحت قيادة مصطفى باشا البيرقدار الذي هو نفسه من الأعيان. وتحرك بقواته تجاه استنبول فما كان من مصطفى الرابع إلا أن قتل سليم لكن الحركة نجحت في التخلص من مصطفى الرابع وتولية محمود الثاني ابن عم سليم الحكم, ومات مصطفى باشا البيرقدار في العام نفسه وظل محمود الثاني في الحكم حتى عام 1838 وكان أول سلطان ينجح في تحقيق الإصلاح.

لقد نجح تمرد 1807 في الإستيلاء على الحكومة المركزية وأما حركات التمرد الأخرى التي قام بها الأعيان والإنكشارية والغاضبون من المسلمين فقد هددت بتقطسع أوصال الدولة. ورغم أن هذا الكتاب معني أساساً بقوميات البلقان المسيحية، إلا أنه من الأهمية بمكان أن نستعرض نشاط ثلاثة حركات تمرد ضد سلطة الدولة قام بها كل من بشفان أوغلو عثمان باشا، وعلي باشا اليانيني نسبة إلى يانينا Janina، ومحمد علي باشا (والي مصر) لأن تمردهم تشابك مع ثورات مسيحي البلقان، بل إن تاريخ حياة كل منهم له أهميته من حيث تصوير مناخ الحياة في البلقان في نهاية القرن الثامن عشر وبداية القرن التاسع عشر الذي تمخض عن انتفاضة المسلمين والمسيحيين ضد الدولة. كماهو حال الزعماء القوميين عادة كان كل منهم يسعى لإقامة حكم مستقل لبلاده بالإنفصال عن الدولة العثمانية أو الفوز بحكم ذاتي على الأقل.

كان لتاريخ بشفان اوغلو عثمان باشا تأثيراً على بدايات ثورة بلاد الصرب وعلى التاريخ القومي لكل من بلغاريا ورومانيا, فعندما أعدمت الحكومة العثمانية والده فر هارباً وانضم إلى المجموعات الخارجة على القانون, ثم حارب إلى جانب الجيش العثماني فيما بعد في حرب 1787-1792. وقد أقام لنشاطه مركزاً في مدينة فيدين على الدانوب جمع فيه قوة كبيرة من قطاع الطرق والمارقين المرتدين. وفي 1795 أعلن استقلاله عن الحكومة العثمانية وظل في ثورة مستمرة ضدها كما سوف نرى عندما نتناول ثورة الصرب.

أما نشاط علي باشا اليانيني الذي يشبه نشاط بشفان اوغلو فكان هو الآخر شيئاً رائعاً فقد ولد في 1750 في تبلينه Teplene في إبيروس (المورة) وعندما مات والده لم يجد أمامه إلا أن يكون قاطع طريق. وبعد عدة مغامرات تتناسب مع شبتبيته استطاع أن يؤسس له قاعدة في يانينا, وتمكن من زيادة قوته وعدد أتباعه عن طريق المكائد والدسائس أحياناً والعنف أحياناً أخر. وفي بداية نشاطه عمل في خدمة الباب العالي واستخدم مواقعه الوظيفية في تقوية نفوذه الشخصي. وعلى هذا وفي 1788 أصبح حاكماً على يانينا حيث تمكن من مد سلطته على الإقليم وعلى الأراضي المحيطة بها في تساليا وإبيروس وألبانيا. ورغم أن المساحة التي كانت تحت سيطرته لم تكن ثابتة خلال السنوات التالية, إلا أنها كانت دائماً كافية لتكون مركز قوة لحكم شبه مستقل. وفي 1799 كان الباب العالي في حاجة ماسة لمساعدة من الرجل نراه يقدم على تعيينه حاكماً على رومليا وهو منصب تولاه أكثر من مرة وفقده أكثر من مرة أيضاً. أما المساعدة التي طلبها الباب العالي منه فكانت التصدي لحركة بشفان اوغلو وقطاع الطرق وزعماء الأعيان, ولما كان اليانيني مهتم بمصالحه الخاصة رأيناه يحتفظ بعلاقات وثيقة مع فرنسا بل لقد قدم مساعدة للباب العالي في 1809 أثناء الحرب ضد روسيا.

وبناء على المساعدات التي كان اليانيني يقدمها للحكم العثماني فقد كان يتصرف كحاكم مستقل من ايبروس له سيادة ومع ذلك تغاضى الباب العالي عن تصرفات الرجل ولم يحاول التخلص منه كما هو متوقع في مثل تلك الحالات. ولكن في عام 1820 وفي ظروف مواتية قام الباب العالي بالتحرك براً وبحراً ضد اليانيني الذي حصن نفسه بعقد اتفاقات مع نبلاء اليونان وأخذ يشجع شعوب البلقان الأخرى على الثورة. لكنه لم يتمكن من مواجهة القوات العثمانية فاضطر إلى الإنسحاب إلى يانينا قاعدته الأولى فحاصرته القوات العثمانية حتى مات في يناير 1822 أثناء الحصار.

أما محمد علي باشا في مصر فكان أكثر تلك الزعامات نجاحاً ورغم أنه أخفق في تحقيق أهدافه الطموحة, إلا أن أبناءه ظلوا يحكمون مصر حتى 1952. وقج ولد في مقدونيا في 1769 من عائلة تركية-ألبانية, وجاء إلى مصر على رأس فرقة ألبانية لإخراج الفرنسيين (1801), وبقى في مصر بعد خروج الفرنسيين ثم بزغ نجمه في الوظائف الإدارية والمهمام العسكرية. ولما كان أستاذا في الدسائس والمؤمرات التي كانت قد تفشت في أنحاء الإمبراطورية العثمانية فقد استطاع إبعاد منافسيه حتى أصبح والياً على مصر في 1805. وخلال الفترة الأولى من ولايته بقى في خدمة الباب العالي مثلما فعل علي باشا اليانيني وفي الوقت نفسه استخدم منصبه الرسمي في تأمين وضعه الشخصي وتقويته. وبفضل مساعدة إبنه إبراهيم باشا تمكن من ضم السودان وإخماد المتمردين في الجزيرة العربية (الحركة الوهابية).

وفي 1825 وعده الباب العالي بالحصول على جزيرة كريت وحصول إبنه إبراهيم على حكم المورة في مقابل القضاء على التمرد في بلاد اليونان الذي عجزت الدولة عن مواجهته. ورغم أن قوات محمد علي نجحت في القضاء على التمرد, إلا أن هزيمة العثمانيين في الحرب مع روسيا 1828-1829 حرمت محمد علي من المكافأة الموعودة. وبسبب هذه النكسة التي ألمت به ورغبته في ضم مزيد من المناطق تحت حكمه قام بغزو بلاد الشام في 1832 وتسبب في كثير من الأزمات لأوروبا. وآنذاك بدت نيته في إيجاد مملكة عربية عظمى مركزها البحر الأحمر وتضم مصر والسودان والجزيرة العربية. وباستثناء كريت والمورة لم يكن محمد علي يهدد بلاد البلقان حيث يقيم المسيحيين بشكل مباشر. على أن محمد علي شأن بشفان اوغلو, وعلي باشا اليانيني كان يمثل محاولة في تقطيع أوصال الإمبراطورية العثمانية وتفتيتها وذلك بتكوين دول منفصلة تحت حكم قادة عسكريون مسلمون. غير أن محمد علي بجيشه العرم الهائل وطبيعة حكمه كان يمثل تهديداً لوجود الدولة العثمانية أكثر مما كانت تمثله ثورات الصربيين واليونانيين.

تحدي القوى العظمى

في الوقت الذي كان الباب العالي يواجه فيه التفكيك الداخلي كان عليه أن يواجه تجدد هجمات القوى الخارجية, فعندما اعتلى سليم الثالث العرش في 1789 كانت حكومته ما تزال في حرب مع النمسا التي كانت قد احتلت بلگراد ثم أعادتها بمقتضى معاهدة سيستوڤا Sistova في 1791 مقابل أن تأخذ النمسا البوسنة, والحرب مع روسيا التي كانت قواتها تتحرك بطول الدانوب إلى أن تم عقد صلح ياصي Jassy في 1792 وبمقتضاه مدت روسيا أرضيها حتى نهر الدنيستر Dinester وتنازلت عن مولداڤيا وولاخيا التي كانت قد احتلتهما. وتعتبر هاتان المعاهدتان خاتمة لقرن من التعاون المتقطع بين النمسا وروسيا ضد العثمانيين. ولكن وبعد انقضاء ثمانين عاماً عليهما هاتين تعاونت الدولتان مرة أخرى للاتفاق على كيفية تقسيم أراضي الدولة العثمانية، وكانت ثمة ظروف قد حالت دون استمرار التعاون.

والحاصل أن القوى العظمى صرفت انتباها عما يحدث في بلاد الشرق الأوسط وركزت اهتمامها على بولندا ثم على فرنسا الثورة، وكانت بولندا قد تعرضت للتقسيم على ثلاث مراحل في 1772, 1793, 1795. واشتعلت الحرب في أوروبا عام 1792. وعلى هذا ظل التركيز الأساسي للعلاقات الأوروبية قائماً على ما يدور في القارة الأوروبية من أحداث كانت لها تداعيات واسعة في كل من البلقان وشرق البحر المتوسط. ففي 1779 وبمقتضى معاهدة كامپو فورميو Campo Formio ضمت فرنسا جزر أيونيا مما كان له تأثيره على ثورة اليونانيين, وحصلت النمسا على بقايا أراضي البندقية وبهذا تم وضع حد للقوى البحرية المستقلة (البندقية) التي كانت في السابق أكبر غريم للعثمانيين.

في يوليو 1798 بدأت فترة من التدخل الفرنسي المباشر في الولايات العثمانية عندما غزا بونابرت مصر وانهزمت أمام جيوشه عساكر المماليك بسرعة ملحوظة وأصبح الباب العالي طرفاً في الصراع ضد فرنسا مع بريطانيا التي ساءها انفراد فرنسا باحتلال مصر. وانتهى الأمر بمعاهدة صلح بين فرنسا وانجلترا في 1802 نصت فيما نصت على خروج الإنجليز من مصر وظلت تلك المعاهدة فاعلة حتى 1806.

على كل حال، ففي فترة التدخل الفرنسي في شؤون الولايات العثمانية زاد نفوذ فرنسا زيادة ملحوظة في السياسة العثمانية حتى لقد ارتبطت الدولة العثمانية بفرنسا ضد كل من روسيا وبريطانيا. ورغم أن الفترة من 1806-1812 لم تشهد معارك مستمرة بين روسيا والدولة العثمانية إلا أن روسيا حاولت استغلال الفرصة لزيادة نفوذها في الصرب وإمارتي الدانوب (ولاخيا ومولداڤيا-رومانيا فيما بعد). وقد انتهى الصراع بين الدولتين بمعاهدة بوخارست 1812 اكتفت فيها روسيا بتنازل الدولةالعثمانية عن بسارابيا والإنسحاب من إمارتي الدانوب برغم موقف العثمانيين الضعيف لأن روسيا كانت معنية آنذاك بأمر غزو بونابرت لأراضيها. وكانت خسائر العثمانيين في هذه التسوية يعد أول تغيير في حدودها نتيجة لحروب الثورة الفرنسية في أوروبا بقيادة بونابرت. وأكثر من هذا أن تسوية ڤيينا (1815) بعد هزيمة بونابرت والتي لم تحضرها الدولة العثمانية قضت بمنح جزر أيونيا لبريطانيا، وساحل دلماشيا لنمسا فكانت بمثابة الإقتطاع الثاني من آفاق الدولة العثمانية.

لقد كان مؤتمر ڤيينا بداية فترة من السلام النسبي بين القوى العظمى في أوروبا دامت قرناً منالزمان فقدت خلاله الدولة العثمانية معظم ممتلكاتها في أوروبا وأثبتت الأيام عجزها عن الدفاع عن وحدة ممتلكاتها أو حتى صيانة استقلالها السياسي دون مساعدة خارجية, ولم تبق دولة عثمانية قائمة إلا بسبب موقع أراضيها الإستراتيجي والحيوي لصالح توسع الدول اللإمبرالية. وفي هذا الخصوص احتلت روسيا وبريطاينا أهمية خاصة إذ أصبح صراعهما على الدلوة العثمانية وعلى البلقان جزء من السباق الإمبريالي الكبير الذي اندلع بين هاتين الدولتين وامتدت ميادينه من شرق البحر المتوسط إلى الصين مروراً بأسيا الصغرى.

والحاصل أن بريطانيا كانت قد استمدت سيطرتها على الهند في القرن الثامن عشر واعتبرتها درة التاج البريطاني, وأصبحت الدولة التجارية والصناعية الأولى في العالم وسيدة البحار ومن ثم كانت تخشى أن ينتزع منها أحد تلك المكانة. وفي نهاية القرن الثامن عشر كانت ترى أن فرنسا زمن بونابرت هي منافستها الرئيسية في العالم بما في ذلك بلاد الشرق الأدنى, ثم أصبحت روسيا هي المنافس بعد القضاء على بونابرت وقبل إعلان دولة ألمانيا. وكانت أراضي الدولة العثمانية من وجهة نظر بريطانيا تمثل مفتاح توسعها الإمبرايالي تجارياً وبحرياً دفاعاً عن الهند ولهذا كانت تخشى دوماً أن تستولي روسيا على تلك الأراضي سواء بالغزو المباشر أو بالسيطرة على الحكومة العثمانية أو بإقامة دولة بلقانية تابعة لها. وبسبب هذا الخوف ظلت بريطانيا ترفع شعار وحدة الأراضي العثمانية وتكاملها طوال القرن التاسع عشر ويقوم سفيرها في استنبول بالضغط على الحكومة العثمانية لإصلاح نظام الحكم والإدارة فيها والسعي للتوفيق بينها وبين شعوب البلقان حفاظاً على الاستقرار.

أما وضع روسيا بالنسبة للدولة العثمانية فكان أكثر تعقيدأ فبعد أن ابتلعت روسيا بساربيا في 1812 كما رأينا لم تضع في حساباتها أن تضم أراضي عثمانية أخرى رغم الفرص التي أتيحت لها لمد نفوذها هنا وهناك فمثلاً كان من الممكن أن تستثمر الحركات القومية بين شعوب البلقان التي كانت تعتبر روسيا أعظم قوة أرثوذكسية وهو شعور كانت روسيا تغذيه كلما سنحت الفرصة. وففي معاهدة كوتشك قينارجي 1774 مع الدولة العثمانية نجحت روسيا في أن تضع بذرة لنوع من إدعائها الحماية الدينية للأرثوذكس ولو بشكل ملتبس وغامض. ولم يكن مسيحيو البلقان ينتظرون فقط المساعدة ن روسيا بل لقد كانت هناك عناصر مهمة بين الروس أنفسهم انجذبت بشدة لفكرة تقديم المساعدة للحركات القومية في البلقان على أسس أرثوذكسية وسلافية. وهكذا وجدت حكومة روسيا نفسها تحت ضغط استغاثات البلقانيين من جهة وتحت ضغط الرأي العام في الداخل من جهة أخرى للقيام بشي ما لمواجهة القهر الذي يتعرض له المسيحيون في البلقان والسلاڤ بشكل عام.

وفي كل الأحوال كانت روسيا تحت إغراء التدخل في الشؤون لعثمانية بطريقة أو بأخرى لتحقيق مكانة ممتازة من ناحية ولتوسيع دائرة قوتها ونفوذها من ناحية أخرى, لم تكن تتصور شأن بريطانيا أن ترى قوة أخرى تسيطر على البلقان. وفي هذا الخصوص كانت روسيا تملك عدة أسلحة قوية في التعامل مع الباب العالي في مقدمتها القوة العسكرية الضخمة والحركات القومية في البلقان. غير أن قادة روسيا كانوا يفضلون إتباع السياسة التي تم إقرارها في معاهدة خونكارية اسكله سي في 1833 التي تقوم على السيطرة على الدولة العثمانية من الداخل.

أما النمسا فكان موقفها بالنسبة للقوى العظمى التي كانت معينة بشؤون البلقان هو الموقف الأضعف نسبياً فيما يبدو, فباعتبارها إمبراطورية متعددة القوميات فإنها قد تكسب قليلاً إذا ما حدث تغيير في أوضاع الممتلكات العثمانية, ومن ناحية أخرى فإن استيلائها على أرضي جديدة في البلقان قد يزيد من مشكلات الأقليات القومية التي تحت سيادتها, ومن ناحية ثالثة فإن تأسيس دول مستقلة في البلقان العثماني قد يشجع مختلف المجموعات القومية تحت حكمها على السير في الطريق نفسه. ورغم أن النمسا كانت تتعاون مع روسيا في إطار سياسة توازن القوى إلا أن قادة النمسا كانوا يدركون في الوقت نفسه مخاطر هذا الطريق إذ لم يكونوا يعتقدون ابدأ بإمكانية هزيمة جيوش روسيا إذا ما اندلعت حرب البلقان بسبب أزمة حقيقية. وعلى هذا وفي إطار تفضيل النمسا لمبدأ المحافظة على وضع الدوةل العثمانية وممتلكاتها كان عليها أن تتعاون مع بريطانيا التي كانت تخشى مثلها توسيع روسيا, وهو تعاون إذا ما تم وضعه في صيغة تحالف فإن النمسا سوف تتحمل الأعباء العسكرية والمخاطر الحقيقية في قيام حرب ضد روسيا على حين سوف تكون الحاجة للبحرية البريطانية منعدمة أو ضئيلة في حالة الحرب البرية ضد روسيا.

أما فرنسا بعد الحروب النابوليونية ورغم مكانتها الهائلة في القرون السابقة إلا أنهما كانت أقل نفوذاً في الإمبراطورية العثمانية بالقياس للقوى الثلاثة الأخرى (روسيا والنمسا وبريطانيا). ورغم أن إيديولوجية الثورة الفرنسية لعبت دوراً كبيراً في الحركات القومية في البلقان إلا أن فرنسا نفسها خلال الفترة من 1815-1848 لم تعد مركزاً للتهيج والإثارة ومع هذا كانت فرنسا في عهد نابليون الثالث تساند الحركات القومية في البلقان غير أن فرنسا بدون جيش على المسرح السياسي وأسطول بحري أقل درجة من أسطول منافستها بريطانيا ترددت في التدخل في صراعات الشرق الأدنى. وفي الوقت نفسه كان لها أهداف في أجزاء من الدولة العثمانية. ففي 1830 احتلت الجزائر، وازدادد نفوذها في مصر. وفي أربعينات وستينات القرن التاسع عشر تدخلت في سوريا ولبنان ولما كانت ترغب في توسيع إمبراطوريتها في إفريقيا وآسيا فقد كانت تساند عادة تكون الدول القومية، وإضعاف الحكومة المركزية، وتعارض أى سياسة قد تؤدي إلى انفراد روسيا أو بريطانيا وخصوصاً في البلقان.

ولما كانت الإمبراطورية العثمانية عاجزة بمفردها عن الدفاع عن نفسها ضد الدول الأوروبية الطامعة فيها فقد اضطرت لأن تتبنى سياسة للتوازن بين القوى العظمى حفاظاً على مصالحها عن طريق ضرب تلك القوى بعضها بالبعض الآخر كلما أمكن ذلك. ولكن في القرن التاسع عشر كان واضحاً أن الدولة تخسر في هذا الصراع إذ نراها تضطر لتقديم تنازل سياسياً وإقتصادياً لصالح أوروبا. وفي الوقت نفسه كانت الحركات القومية في البلقان العثماني تحقق تقدماً ملحوظاً بفضل مساندة إحدى الدول الأوروبية أو كل من الدول الأوروبية مجتمعة. ورغم أن مسيحي البلقان هم الذين بدأوا الثورة إلا أن القوى العظمى هي التي صنعت في النهاية خريطة الدول القومية الجديدة بحدودها وشكل حكومتها. وفي هذا الخصوص كان الزعماء الأوروبيون في الإجراءات التي اتخذوها أبعد ما يكونوا عن الإيثار ونكران الذات إذ وضعوا في إعتبارهم مصالحهم الخاصة والمحافظة على توازن القوى, وهي اعتبارات كانت تستخمها في مختلف مغامراتها الإستعمارية ولم يكن أمام الإمبراطورية العثمانية بل ودول البلقان الجديدة إلا الخضوع لها.

وهكذا، بحلول القرن التاسع عشر كانت الأحوال السائدة في البلقان في صالح تمرد المسيحيين، ولم يكن باستطاعة الحكومة العثمانية السيطرة على النبلاء المتمردين أو هزيمة الجيوس الأجنبية. وأثناء اضطراب المواقف تمكنت قايدات عسكرية قوية من السيطرة على مراكز السلطة المحلية مما ساعد على بلورة تقاليد التمرد. ومن هذا المناخ وتلك الظروف انبثقت حركات التمرد عند مسيحيي البلقان. وكانت ثورة الصرب أول الثورات اتصالاً بمعنى فشل الحكومة العثمانية في المحافظة على سلطتها في المراكز المحلية وكذا ضعفها أمام خصومها.

الحرب العالمية الأولى

انظر أيضاً

معرض الصور

الهوامش

- ^ ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- ^ L. S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453 (London: Hurst and Co., 2000), pp. 248–250.

- ^ (Kinross 1977, pp. 457)

- ^ http://faith-matters.org/images/stories/fm-publications/the-tanzimat-final-web.pdf

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ PTT Chronology Archived سبتمبر 13, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت ث "History of the Turkish Postal Service". Ptt.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Istanbul City Guide: Beylerbeyi Palace Archived أكتوبر 10, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب NTV Tarih Archived 2013-02-12 at the Wayback Machine history magazine, issue of July 2011. "Sultan Abdülmecid: İlklerin Padişahı", page 49. (Turkish)

- ^ أ ب ت Türk Telekom: History Archived سبتمبر 28, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب NTV Tarih Archived 2013-02-12 at the Wayback Machine history magazine, issue of July 2011. "Sultan Abdülmecid: İlklerin Padişahı", pages 46–50. (Turkish)

- ^ "Ottoman Bank Museum: History of the Ottoman Bank". Obarsiv.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Istanbul Stock Exchange: History of the Istanbul Stock Exchange". Imkb.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History (2012)

- ^ Royle. Preface.

- ^ "History of the Ottoman public debt". Gberis.e-monsite.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Douglas Arthur Howard: "The History of Turkey", page 71.

- ^ "Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to the Ottoman Empire" Archived يونيو 11, 2007 at the Wayback Machine, by Bryan Glynn Williams, Cahiers du Monde russe, 41/1, 2000, pp. 79–108.

- ^ Memoirs of Miliutin, "the plan of action decided upon for 1860 was to cleanse [ochistit'] the mountain zone of its indigenous population", per Richmond, W. The Northwest Caucasus: Past, Present and Future. Routledge. 2008.

- ^ Justin McCarthy, Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821–2000, Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, c1995

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Stone, Norman "Turkey in the Russian Mirror" pages 86–100 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Mark & Ljubica Erickson, Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, 2004 page 95.

- ^ Tehmina Kazi (7 Oct 2011). "The Ottoman empire's secular history undermines sharia claims". UK Guardian.

- ^ Barsoumian, Hagop. "The Eastern Question and the Tanzimat Era", in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) New York: St. Martin's Press, p. 198. ISBN 0-312-10168-6.

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 (1954) pp 228–54

- ^ Jerome L. Blum, et al. The European World: A History (1970) p 841

- ^ Mann, Michael (2005), The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing, Cambridge University Press, p. 118

- ^ Todorova, Maria (2009), Imagining the Balkans, Oxford University Press, p. 175

- ^ editors: Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen, Immigration and Asylum: From 1900 to the Present, Vol. 1, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p.437 Read quote: "Muslims had been the majority in Anatolia, the Crimea, the Balkans and the Caucasus and a plurality in southern Russia and sections of Romania. Most of these lands were within or contiguous with the Ottoman Empire. By 1923, only Anatolia, eastern Thrace and a section of the south-eastern Caucasus remained to the Muslim land."

- ^ أ ب ت Dr. Bayram Kodaman, The Hamidiye Light Cavalry Regiments (Abdullmacid II and Eastern Anatolian Tribes)

- ^ أ ب M.Sükrü Hanioglu, A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, 129.

- ^ M.Sükrü Hanioglu, A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, 130.

- ^ (Karpat 1978, pp. 237–274)

- ^ (Shaw 1978, pp. 323–338)

- ^ "Map of Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the year 1900". Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. "The Armenian Question in the Ottoman Empire, 1876–1914". The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. II: 218.

- ^ أ ب (McDowall 2004, pp. 42–47)

- ^ Ter-Minasian, Ruben. Hai Heghapokhakani Me Hishataknere [Memoirs of an Armenian Revolutionary] (Los Angeles, 1952), II, 268–269.

- ^ Darbinian, op. cit., p. 123; Adjemian, op. cit., p. 7; Varandian, Dashnaktsuthian Patmuthiun, I, 30; Great Britain, Turkey No. 1 (1889), op. cit., Inclosure in no. 95. Extract from the "Eastern Express" of 25 June 1889, pp. 83–84; ibid., no. 102. Sir W. White to the Marquis of Salisbury-(Received 15 July), p. 89; Great Britain, Turkey No. 1 (1890), op. cit., no. 4. Sir W. White to the Marquis of Salisbury-(Received 9 August), p. 4; ibid., Inclosure 1 in no. 4, Colonel Chermside to Sir W. White, p. 4; ibid., Inclosure 2 in no. 4. Vice-Consul Devey to Colonel Chermside, pp. 4–7; ibid., Inclosure 3 in no. 4. M. Patiguian to M. Koulaksizian, pp. 7–9; ibid., Inclosure 4 in no.

- ^ أ ب ت Creasy, Edward Shepherd. Turkey, pg.500.

- ^ Astourian, Stepan (2011). "The Silence of the Land: Agrarian Relations, Ethnicity, and Power," in A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire, eds. Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Müge Göçek, and Norman Naimark. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 58-61, 63-67.

- ^ أ ب Summary of Janet Klein’s Power in the Periphery: The Hamidiye Light Cavalry and the Struggle over Ottoman Kurdistan, 1890-1914.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford J. and Ezel Kural Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, vol. 2, p. 246.

- ^ (McDowall 2004, pp. 59)

- ^ Safrastian, Arshak. 1948 Kurds and Kurdistan. Harvill Press, pg 66.

- ^ (McDowall 2004, pp. 59–60)

- ^ (McDowall 2004, pp. 60)

- ^ (McDowall 2004, pp. 61–62)

- ^ Janet Klein, Joost Jongerden, Jelle Verheij, Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1975, 152

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, p. 217. ISBN 0-312-10168-6.

- ^ (McDowall 2004, pp. 61)

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun, Volume III (in Armenian). Athens, Greece: Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Ousoumnagan Khorhourti. pp. 42–44.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Denise Natali. The Kurds and the State. (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2005)

- ^ Balakian, Peter. The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. New York: Perennial, 2003. pp. 107–108