نهر دنيستر

| Dniester | |

|---|---|

Rîbnița and the Dniester river | |

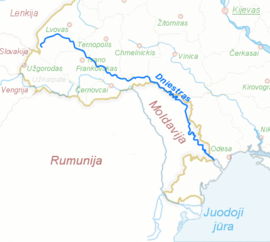

خريطة حوض الدنيستر | |

| الموقع | |

| البلدان | أوكرانيا, مولدوڤا, (incl. ترانسنيستريا) |

| المدن | تيراسپول، بندر، Rîbnița, Drohobych |

| السمات الطبيعية | |

| المنبع | الكرپات الأوكرانية |

| ⁃ الموقع | الجبال البسكية الشرقية (الكرپات الأوكرانية) |

| ⁃ الإحداثيات | 49°12′44″N 22°55′40″E / 49.21222°N 22.92778°E |

| ⁃ المنسوب | 900 متر |

| المصب | البحر الأسود |

- الموقع | أبلاست أوديسا |

- الإحداثيات | 46°21′0″N 30°14′0″E / 46.35000°N 30.23333°E |

- المنسوب | 0 متر |

| الطول | 1,362 كم |

| مساحة الحوض | 68,627 كم² |

| التدفق | |

| ⁃ المتوسط | 310 m3/s (11,000 cu ft/s) |

| سمات الحوض | |

| الروافد | |

| - اليسرى | مورافا, Smotrych, Zbruch, Seret, ستريپا, زولوتا ليپا، Stryi |

| - اليمنى | بوتنا, Bîc, Răut, Svicha, Lomnytsia, Ichel |

| الاسم الرسمي | الدنيستر الأسفل |

| التوصيف | 20 August 2003 |

| الرقم المرجعي | 1316[1] |

| الاسم الرسمي | وادي نهر دنيستر |

| التوصيف | 20 March 2019 |

| الرقم المرجعي | 2388[2] |

نهر دنيستر (![]() /ˈniːstər/ NEES-tər;[3] رومانية: Nistru، أوكرانية: Дністе́р التحريف Dnister؛ إنگليزية: Dniester river؛ تركية: Turla) هو نهر يجري في شرق أوروبا. ينبع نهر دنيستر من جبال الكربات في غرب اوكرانيا قرب مدينة دروهوبيتش قرب الحدود مع بولندا. ويجري النهر في اتجاه الجنوب الشرقي لمسافة 1,408 كم عبر غربي أوكرانيا، يشكل جزء من مساره جزءا من الحدود بين أوكرانيا ومولدافيا. ومن ثم يدخل مولدافيا، ثم يعرج مرة أخرى ليدخل أوكرانيا من جنوبها ليصب في البحر الأسود. وتبحر السفن الصغيرة في النهر حتى مدينة خوتين في غربي أوكرانيا.

/ˈniːstər/ NEES-tər;[3] رومانية: Nistru، أوكرانية: Дністе́р التحريف Dnister؛ إنگليزية: Dniester river؛ تركية: Turla) هو نهر يجري في شرق أوروبا. ينبع نهر دنيستر من جبال الكربات في غرب اوكرانيا قرب مدينة دروهوبيتش قرب الحدود مع بولندا. ويجري النهر في اتجاه الجنوب الشرقي لمسافة 1,408 كم عبر غربي أوكرانيا، يشكل جزء من مساره جزءا من الحدود بين أوكرانيا ومولدافيا. ومن ثم يدخل مولدافيا، ثم يعرج مرة أخرى ليدخل أوكرانيا من جنوبها ليصب في البحر الأسود. وتبحر السفن الصغيرة في النهر حتى مدينة خوتين في غربي أوكرانيا.

الأسماء

الاسم دنيستر مشتق من الصرماتية dānu nazdya "the close river."[4] (The Dnieper, also of Sarmatian origin, derives from the opposite meaning, "the river on the far side".) Alternatively, according to Vasily Abaev Dniester would be a blend of Scythian dānu "river" and Thracian Ister, the previous name of the river, literally Dān-Ister (River Ister).[5] The Ancient Greek name of Dniester, Tyras (Τύρας), is from Scythian tūra, meaning "rapid."[بحاجة لمصدر]

The names of the Don and Danube are also from the same Indo-Iranian word *dānu "river". Classical authors have also referred to it as Danaster. These early forms, without -i- but with -a-, contradict Abaev's hypothesis.[بحاجة لمصدر] Edward Gibbon refers to the river both as the Niester and Dniester in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.[6]

In Ukrainian, it is known as Дністе́р (translit. Dnister), and in Romanian as Nistru. In Russian, it is known as Днестр (translit. Dnestr), in Yiddish: Nester נעסטער; in Turkish, Turla; and in Lithuanian as Dniestras.

الجغرافيا

The Dniester rises in Ukraine, near the city of Drohobych, close to the border with Poland, and flows toward the Black Sea. Its course marks part of the border of Ukraine and Moldova, after which it flows through Moldova for 398 kilometres (247 mi), separating the main territory of Moldova from its breakaway region Transnistria. It later forms an additional part of the Moldova-Ukraine border, then flows through Ukraine to the Black Sea, where its estuary forms the Dniester Liman.

Along the lower half of the Dniester, the western bank is high and hilly while the eastern one is low and flat. The river represents the de facto end of the Eurasian Steppe. Its most important tributaries are Răut and Bîc.

التاريخ

The Dniester in Khotyn (western Ukraine). Another Moldavian fortress and an Orthodox church seen on foreground. |

During the Neolithic, the Dniester River was the centre of one of the most advanced civilizations on earth at the time. The Cucuteni–Trypillian culture flourished in this area from roughly 5300 to 2600 BC, leaving behind thousands of archeological sites. Their settlements had up to 15,000 inhabitants, making them among the first large farming communities in the world.[7]

In antiquity, the river was considered one of the principal rivers of European Sarmatia, and it was mentioned by many Classical geographers and historians. According to Herodotus (iv.51) it rose in a large lake, whilst Ptolemy (iii.5.17, 8.1 &c.) places its sources in Mount Carpates (the modern Carpathian Mountains), and Strabo (ii) says that they are unknown. It ran in an easterly direction parallel with the Ister (lower Danube), and formed part of the boundary between Dacia and Sarmatia. It fell into the Pontus Euxinus to the northeast of the mouth of the Ister, the distance between them being 900 stadia – approximately 210 km (130 mi) – according to Strabo (vii.), while 210 km (130 mi) (from the Pseudostoma) according to Pliny (iv. 12. s. 26). Scymnus (Fr. 51) describes it as of easy navigation, and abounding in fish. Ovid (ex Pont. iv.10.50) speaks of its rapid course.

Greek authors referred to the river as Tyras (باليونانية: ὁ Τύρας).[8] At a later period it obtained the name of Danastris or Danastus,[9] whence its modern name of Dniester (Niester), though the Turks still called it Turla during the 19th century.[10] The form Τύρις is sometimes found.[11]

According to Constantine VII, the Varangians used boats on their trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, along Dniester and Dnieper and along the Black Sea shore. The navigation near the western shore of Black Sea contained stops at Aspron (at the mouth of Dniester), then Conopa, Constantia (localities today in Romania) and Messembria (today in Bulgaria).

From the 14th century to 1812, part of the Dniester formed the eastern boundary of the Principality of Moldavia.

Between the World Wars, the Dniester formed part of the boundary between Romania and the Soviet Union. In 1919, on Easter Sunday, the bridge was blown up by the French Army to protect Bender from the Bolsheviks.[12] During World War II, German and Romanian forces battled Soviet troops on the western bank of the river.

After the Republic of Moldova declared its independence in 1991, the small area to the east of the Dniester that had been part of the Moldavian SSR refused to participate and declared itself the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, or Transnistria, with its capital at Tiraspol on the river.

الروافد

From source to mouth, right tributaries, i.e. on the southwest side, are the Stryi (231 km or 144 mi), Svicha (107 km or 66 mi), Limnytsia (122 km or 76 mi), Bystrytsia (101 km), Răut (283 km or 176 mi), Ichel (101 km or 63 mi), Bîc (155 km or 96 mi), and Botna (152 km or 94 mi).

Left tributaries, on the northeast side, are the Strwiąż (94 km or 58 mi), Zubra, Hnyla Lypa (87 km or 54 mi), Zolota Lypa (140 km or 87 mi), Koropets (78 km or 48 mi), Strypa (147 km or 91 mi), Seret (250 km or 160 mi), Zbruch (245 km or 152 mi), Smotrych (169 km or 105 mi), Ushytsia (122 km or 76 mi), Zhvanchyk (107 km or 66 mi), Liadova (93 km or 58 mi), Murafa (162 km or 101 mi), Rusava (78 km or 48 mi), Yahorlyk (73 km or 45 mi), and Kuchurhan (123 km or 76 mi).[13]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ "Lower Dniester". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ "Dnister River Valley". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ قاموس مريام-وبستر: "Dniester"

- ^ Mallory, J.P. and Victor H. Mair. The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000. p. 106

- ^ Абаев В. И. Осетинский язык и фольклор (tr. "Ossetian language and folklore"). Moscow: Publishing house of Soviet Academy of Sciences, 1949. P. 236

- ^ Edward Gibbon. Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol 1 chapt 11

- ^ Mikhail Widejko (Відейко М. Ю.). "Трипільські протоміста. Історія досліджень. Київ 2002; с. 103–125" [Trypillya culture proto-cities. History of investigations. Kyiv 2002, p. 103–125)]. Iananu.kiev.ua. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ^ Strabo ii.

- ^ Amm. Marc. xxxi. 3. § 3; Jornand. Get. 5; Const. Porphyr. de Adm. Imp. 8

- ^ Herod. iv. 11, 47, 82; Scylax, p. 29; Strab. i. p. 14; Mela, ii. 1, etc.; also Schaffarik, Slav. Alterth. i. p. 505.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, p. 671; Suid. s. v.

- ^ Kaba, John (1919). Politico-economic Review of Basarabia. United States: American Relief Administration. p. 15. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Dnister River Encyclopedia of Ukraine, accessed 15 December 2022

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography by William Smith (1856).

وصلات خارجية

| Dniester

]]. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 8 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 349.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 8 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 349. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)- Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Ivan Teslia, Dnister River in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).

- Dniester.org: a trans-boundary Dniester river project

- eco-tiras.org

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing رومانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2014

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2023

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- دنيستر

- حوض الدنيستر

- أنهار اوكرانيا

- أنهار مولدوڤا

- الأنهار الدولية في اوروپا

- حدود أوكرانيا-مولدوڤا

- Ramsar sites in Moldova

- Ramsar sites in Ukraine

- Rivers of Transnistria

- Rivers of Lviv Oblast

- Rivers of Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast

- Rivers of Ternopil Oblast

- Rivers of Chernivtsi Oblast

- Rivers of Khmelnytskyi Oblast

- Rivers of Vinnytsia Oblast

- Rivers of Odesa Oblast

- صفحات مع الخرائط