سينالوا

Sinaloa | |

|---|---|

| ولاية سينالوا الحرة ذات السيادة Estado Libre y Soberano de Sinaloa (بالإسبانية) | |

| الكنية: أرض الأحد عشر نهراً | |

| النشيد: نشيد ولاية سينالوا | |

ولاية سينالوا ضمن المكسيك | |

| الإحداثيات: 25°0′N 107°30′W / 25.000°N 107.500°W | |

| البلد | |

| العاصمة وأكبر مدينة | Culiacán |

| Municipalities | 18 |

| Admission | October 14, 1830[1] |

| الترتيب | 20 |

| الحكومة | |

| • الحاكم | Quirino Ordaz Coppel (PRI) |

| • Senators[2] | Imelda Castro Castro Rubén Rocha Moya Mario Zamora Gastélum |

| • النواب[3] | |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 58٬328 كم² (22٬521 ميل²) |

| Ranked 17th | |

| أعلى منسوب | 2٬815 m (9٬236 ft) |

| التعداد (2020)[6] | |

| • الإجمالي | 3٬026٬943 |

| • الترتيب | 16th |

| • الكثافة | 52/km2 (130/sq mi) |

| • ترتيب الكثافة | 18th |

| صفة المواطن | Sinaloense |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| Postal code | 80-82 |

| Area code | |

| ISO 3166 code | MX-SIN |

| HDI | ▲ 0.804 very high Ranked 5th |

| GDP | US$ 13,749,376,250 [a] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | Official Web Site |

| ^ a. The state's GDP was $175,992,016 thousand of pesos in 2008,[7] amount corresponding to $13,749,376.25 thousand of dollars, being a dollar worth 12.80 pesos (value of June 3, 2010).[8] | |

سينالوا (النطق الإسپاني: [sinaˈloa])، واسمها الرسمي Estado Libre y Soberano de Sinaloa ("الولاية الحرة ذات السيادة سينالوا")، هي واحدة من 31 ولاية بالمكسيك تشكل مع مدينة المكسيك التقسيمات الادارية في المكسيك. وتنقسم إلى 18 بلدية وعاصمتها كولياكان روزالس.

وتقع في شمال غرب المكسيك، وتحدها ولايات سونورا إلى الشمال، تشيواوا و دورانگو إلى الشرق (يفصلها عنهما سييرا مادرى أوكسيدنتال) وإلى الجنوب ناياريت. إلى الغرب، تواجه سينالوا باها كاليفورنيا سور عبر خليج كاليفورنيا. تبلغ مساحة الولاية 58,328 كم²، وتضم جزر پالميتو ڤردى، و پالميتو دلا ڤيرگن، ألتامورا و سانتا ماريا، وسالياكا وماكاپولى وسان إگناسيو. بالاضافة للعاصمة، مدن الولاية الهامة تضم مازاتلان ولوس موتشيس.

أصل الاسم

Sinaloa combines two words from the Cahita language: sina ('pithaya plant'), and lobola ('rounded'); "sinalobola" was shortened to "sinaloa".[9] This most popular etymology is attributed to Eustaquio Buelna. Another etymology attributed to Pablo Lizárraga is Mexica cintli ('dry corn and cob') and ololoa ('to pile up'), and to locative, "where they pile up or store corn on the cob." Yet another etymology from Héctor R. Olea combinsa Cahia sina with the locative "ro" from the Purépecha language and "a" from Aztec atl ('water'), thus "place of pithayas in the water.[10]

التاريخ

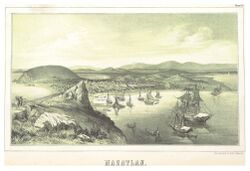

Lithograph of Mazatlán in 1845 |

Sinaloa belongs to the northern limit of Mesoamerica. From the Fuerte River to the north is the region known as Aridoamerica, which includes the deserts and arid places of northern Mexico and southwestern United States. Before European contact, the territory of Sinaloa was inhabited by groups such as the Cahitas, the Tahues, the Acaxees, the Xiximes, the Totorames, the Achires and the Guasaves.[11]

In 1531, Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, with a force of over 10,000 men, established a Spanish and allied Indian outpost at San Miguel de Culiacán. Over the next decade, the Cahíta suffered severe depopulation from conquest, smallpox and other diseases brought by Europeans.[12]

The Spanish organized Sinaloa as part of the gobierno of Nueva Galicia. In 1564, the area was realigned: the area of Culiacán and Cosalá remained in control of Nueva Galicia, while the areas to the north, south and west were made part of the newly formed Nueva Vizcaya province, making the Culiacán area an exclave of Nueva Galicia. The first capital of Nueva Vizcaya was located in San Sebastián, near Copala, but was moved to Durango in 1583.[13]

Starting in 1599, Jesuit missionaries spread out from a base at what is now Sinaloa de Leyva and by 1610, the Spanish influence had been extended to the northern edge of Sinaloa. In 1601, the Jesuits' movement into the eastern part of Sinaloa led to the Acaxee going to war. The Spanish eventually managed to reassert authority in the Sierra Madre Occidental region and executed 48 Acaxee leaders.[14]

After the Mexican War of Independence, Sinaloa was joined with Sonora as Estado de Occidente, but became a separate, sovereign state in 1830.[12] The Porfiriato era was marked by the administration of Francisco Cañedo, who served multiple non-consecutive terms from 1877 to 1909. After the Mexican Revolution, infrastructure projects and land reform consolidated the agrarian sector, which led to the state being named "the granary of Mexico".[15]

الجغرافيا

The coastal plain is a narrow strip of land that stretches along the length of the state and lies between the Gulf of California and the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range, which dominates the eastern part of the state. Sinaloa is traversed by many rivers, which carve broad valleys into the foothills. The largest of these rivers are the Culiacán, Fuerte, and Sinaloa.[16]

Sinaloa has a warm climate on the coast; moderately warm climate in the valleys and foothills; moderately cold in the lower mountains, and cold in the higher elevations. Its weather characteristics vary from subtropical and tropical, found on coastal plains, to cold in the nearby mountains. Temperatures range from 22 °C (72 °F) to 43 °C (109 °F) with rain and thunderstorms during the rainy season (June to October) and dry conditions throughout most of the year. Its average annual precipitation is 790 millimetres.[17]

Numerous species of plants and animals are found within Sinaloa. Notable among the tree species is the elephant tree, Bursera microphylla.[18]

التوزيع السكاني

| الترتيب | Municipality | التعداد | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Culiacán Rosales  Mazatlán |

1 | Culiacán Rosales | Culiacán | 808,416 |  Los Mochis  Guasave | ||||

| 2 | Mazatlán | Mazatlán | 441,975 | ||||||

| 3 | Los Mochis | Ahome | 298,009 | ||||||

| 4 | Guasave | Guasave | 77,849 | ||||||

| 5 | Guamúchil | Salvador Alvarado | 65,215 | ||||||

| 6 | Escuinapa de Hidalgo | Escuinapa | 33,924 | ||||||

| 7 | Licenciado Benito Juárez | Navolato | 33,496 | ||||||

| 8 | Navolato | Navolato | 30,796 | ||||||

| 9 | Costa Rica | Culiacán | 28,239 | ||||||

| 10 | Gabriel Leyva Solano | Guasave | 25,157 | ||||||

| السنة | تعداد | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1895 | 261٬050 | — |

| 1900 | 296٬701 | +2.59% |

| 1910 | 323٬642 | +0.87% |

| 1921 | 341٬265 | +0.48% |

| 1930 | 395٬618 | +1.66% |

| 1940 | 492٬821 | +2.22% |

| 1950 | 635٬681 | +2.58% |

| 1960 | 838٬404 | +2.81% |

| 1970 | 1٬266٬528 | +4.21% |

| 1980 | 1٬849٬879 | +3.86% |

| 1990 | 2٬204٬054 | +1.77% |

| 1995 | 2٬425٬675 | +1.93% |

| 2000 | 2٬536٬844 | +0.90% |

| 2005 | 2٬608٬442 | +0.56% |

| 2010 | 2٬767٬761 | +1.19% |

| 2015 | 2٬966٬700 | +1.40% |

| 2020 | 3٬026٬943 | +0.40% |

| Source: [20] | ||

According to the 2020 census, Sinaloa is home to 3,026,943 inhabitants, 60% of whom reside in the capital city of Culiacán and the municipalities of Mazatlán and Ahome. It is a young state in terms of population, 56% of which is younger than 30 years of age.[21]

Other demographic particulars report 87% of the state practices the Catholic faith. Also, 1% of those over five years of age speak an indigenous language alongside Spanish; the main indigenous ethnic group residing in the state is the Mayo or "Yoreme" (Cáhita language) people. Life expectancy in the state follows the national tendency of higher rates for women than men, a difference of almost six years in the case of Sinaloa, at 74.2 and 68.3 years respectively.[22]

In ethnic composition, Sinaloa has received large historic waves of immigration from Europe (mainly Spain, the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, Austria, Italy and Russia) and Asia (namely China, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Armenia, Lebanon, and Syria). The last two countries also make up most of the Arab Mexican community in the state. In recent years, retirees from the U.S., Canada, Australia, and South America have arrived and made Sinaloa their home.[23]

There was also a sizable influx of Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Greeks form a notable presence in Sinaloa, where one can find local cuisine with kalamari and a few Greek Orthodox churches along the state's coast.[24]

According to the 2020 Census, 1.39% of Sinaloa's population identified as Black, Afro-Mexican, or having African descent.[25]

Sinaloenses have moved to the United States in large numbers since 1970; a large community lives in the twin towns of Indio, California and Coachella, California about 25 miles east of the resort city of Palm Springs, California in the Colorado Desert of Southern California.

Economy

The main economic activities of Sinaloa are agriculture, fishing, livestock breeding, tourism and food processing.[26] Sinaloa has on its license plates the image of a tomato, as the state is widely recognized for harvesting this particular fruit in great abundance from Los Mochis in the North to Culiacán in the central region of the state. Agriculture produce aside from tomatoes include cotton, beans, corn, wheat, sorghum, potatoes, soybeans, mangos, sugarcane, peanuts and squash.[27] Sinaloa is the most prominent state in Mexico in terms of agriculture and is known as "Mexico's breadbasket". Additionally, Sinaloa has the second largest fishing fleet in the country.[28] Livestock produces meat, sausages, cheese, milk as well as sour cream.

التعليم

In terms of education, average schooling reaches 8.27 years; 4.2% of those over 15 years of age are illiterate, and 3.18% of children under 14 years of age do not attend school.[29]

Institutions of higher education include Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, TecMilenio University, Universidad Politécnica de Sinaloa, Universidad Politécnica del Mar y la Sierra, Universidad Politécnica del Valle del Evora, Universidad Autónoma de Durango, Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Sinaloa, Universidad Autónoma de Occidente and Universidad Casa Blanca.

Government and politics

The current governor of Sinaloa is Rubén Rocha Moya.[30] The state is represented in the Mexican Congress by three Senators in the upper house and fourteen federal deputies in the lower house.

Municipalities

Sinaloa is divided into 18 municipalities. Each municipality has a city council, headed by the municipal president. The aforementioned positions have a duration of three years.[31]

The state's major cities include the capital and largest city, Culiacán, Mazatlán, a famous tourist resort and destination, and Los Mochis, an agricultural hub in Northwestern Mexico. Other cities include Guasave, Guamúchil, Escuinapa, El Fuerte, Sinaloa de Leyva, El Rosario, San Ignacio de Piaxtla and Choix.

Culture

Culturally, Sinaloa is part of Northern Mexico. Famous entertainers from the state include actor Pedro Infante, born in Mazatlán; singer Ana Gabriel, born in Guamúchil; singer and actress Lola Beltrán from Rosario; Cruz Lizárraga, the founder of Banda el Recodo; baseball player Jorge Orta, from Mazatlán; actress/comedian/singer Sheyla Tadeo, born in Culiacán; actress Sabine Moussier; actress/singer Lorena Herrera, from Mazatlán; and singer-songwriter Chalino Sánchez, from Las Flechas, Culiacán.

Music

The state is known for its popular styles of music banda and norteño.[32] Banda was established in the early 1920s, influenced by the organological style of the European fanfare, and incorporating traditional sones, ranchera, corrido, polka, waltz, mazurka and schottische predominate, as well as more contemporary genres such as cumbia.[33]

The first bandas were formed by members of military and municipal bands who settled in the Sierra Madre Occidental during the Mexican Revolution, and were influenced by traditional Yoreme music.[33]

Cuisine

Its rich cuisine is well known for its variety particularly in regard to mariscos (seafood) and vegetables. Famous dishes include aguachile.[34][35] Sinaloan sushi is a popular dish.[36]

Media

Newspapers of Sinaloa include: El Debate de Culiacán, El Debate de Guamúchil, El Debate de Guasave, El Debate de los Mochis, El Debate de Mazatlán, El Sol de Culiacán, El Sol de Sinaloa, La I Noticias para Mí Culiacán, Noroeste (Culiacán), Noroeste de Mazatlán, and Primera Hora.[37][38]

Sports

Sinaloa is one of the few places where the ancient Mesoamerican ballgame is still played, in a handful of small, rural communities not far from Mazatlán. The ritual ballgame was central in the society, religion and cosmology of all the great Mesoamerican cultures including the Mixtecs, Aztecs, and Maya.[39] The Sinaloa version of the game is called ulama and is very similar to the original.[40] There are efforts to preserve this 3500-year-old unique tradition by supporting the communities and children who play it.[41]

The state is home to several baseball teams such as Tomateros de Culiacán, Venados de Mazatlán, Cañeros de Los Mochis and Algodoneros de Guasave which take part in the Mexican Pacific League.[42]

Organized crime

The powerful Sinaloa Cartel (Cártel de Sinaloa or CDS) has significantly influenced the culture of Sinaloa.[43] The cartel is reportedly the largest drug trafficking, money laundering and organized crime syndicate in the Americas; it is based in the city of Culiacán, Sinaloa.[44]

Notable people

- Adán Sánchez - Singer

- Chalino Sánchez – Singer

- Carlos Bojórquez – Boxer

- Julio César Chávez – Six time World Boxing Champion

- Jorge Orta – Major League Baseball player

- Jorge Arce – Boxer and flyweight champion

- Cristobal Arreola – Boxer

- Luis Ayala – Major League Baseball player

- Sandra Avila Beltrán – Drug Lord

- Lola Beltrán – Actress and Ranchera singer

- Perla Beltrán Acosta – Beauty queen, model and entrepreneur

- Paul Aguilar — Football Player

- Heraclio Bernal – Social Agitator/Folk Hero

- Jared Borgetti – Football player

- Omar Bravo – Football player

- Ariel Camacho – Norteño Singer/Folk Songs

- Javier Valdez Cárdenas – Journalist

- Oscar Dautt – Football player

- Iván Estrada – Football player

- Carlos Fierro – Football player

- Rodolfo Fierro - Revolutionary Fighter

- Ana Gabriel – Singer

- Pedro Avilés Pérez – Drug Lord

- Joaquín Guzmán Loera – Former leader and co-founder of the Sinaloa Cartel.

- Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo – Former leader and co-founder of the Guadalajara Cartel.

- Rafael Caro Quintero – Former leader and founder of the Sonora Cartel.

- Amado Carrillo Fuentes – Former leader and co-founder of the Juárez Cartel.

- Alfredo Beltrán Leyva – Leader and co-founder of the Beltrán-Leyva Organization.

- Héctor Luis Palma Salazar – Former leader and co-founder of the Sinaloa Cartel.

- Ismael Zambada García – Leader of the Sinaloa Cartel.

- Benjamín Arellano Félix – Former leader and co-founder of the Tijuana Cartel (Arellano Félix Organization.)

- Ramón Arellano Félix – Former leader and co-founder of the Tijuana Cartel (Arellano Félix Organization.)

- Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo – Former leader and co-founder of the Guadalajara Cartel.

- Enedina Arellano Félix – Leader and co-founder of the Tijuana Cartel (Arellano Félix Organization.)

- Lorena Herrera – Actress

- Pedro Infante – Singer and actor

- Francisco Labastida – Economist and politician affiliated to the PRI

- Horacio Llamas – Basketball player

- Los Tigres del Norte – Norteño music group

- Banda el Recodo – Banda Sinaloense

- Jesús Malverde – Folklore hero

- Alberto Medina – Football player

- César Millán – TV personality and professional dog trainer

- Fernando Montiel – Boxer

- Héctor Moreno – Football player

- Sabine Moussier – Actress

- Patricia Navidad – Actress and singer

- Antonio Osuna – Major League Baseball player

- Roberto Osuna – Major League Baseball player

- Óliver Pérez – Major League Baseball player

- Fausto Pinto – Football player

- Julio Preciado – Singer

- José Luis Ramírez – Boxer

- Sara Ramírez – Actress

- Paul Rodriguez – Comedian

- Aurelio Rodríguez – Major League Baseball player

- Dennys Reyes – Major League Baseball player

- Sheyla Tadeo – Actress and comedian

- María del Rosario Espinoza – Taekwondo Olympic medalist

- Roberto Tapia – Singer

- Julio Urías – Major League Baseball player

- José Urquidy – Major League Baseball player

- Chayito Valdez – Folk singer

- Banda MS - Banda Sinaloense

- La Arrolladora Banda El Limon - Banda Sinaloense

- Banda Los Recoditos - Banda Sinaloense

- José Manuel López Castro - Norteño Singer

- Ozziel Herrera - Football player

See also

- Sinaloa Cartel

- Las Labradas, an archaeological site located in southern Sinaloa

References

- ^ "Ley. Reglas para la división del Estado de Sonora y Sinaloa" (in الإسبانية).

- ^ "Senadores por Sinaloa LXI Legislatura". Senado de la Republica. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ "Listado de Diputados por Grupo Parlamentario del Estado de Sinaloa". Camara de Diputados. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ "Resumen". Cuentame INEGI. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ^ "Relieve". Cuentame INEGI. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ "México en cifras". January 2016.

- ^ "Mexico en Cifras". INEGI. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ "Reporte: Jueves 3 de Junio del 2010. Cierre del peso mexicano". www.pesomexicano.com.mx. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Sinaloa, National Park Service

- ^ "Municipio de Sinaloa de Leyva". Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ Ortega Noriega, Sergio (1999). Breve historia de Sinaloa. Colegio de México, Fideicomiso Historia de las Américas. ISBN 968-16-5378-5. OCLC 42398419. Retrieved 2021-08-08.

- ^ أ ب Nakayama A., Antonio (1996). Sinaloa : un bosquejo de su historia. Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa. ISBN 968-6063-98-6. OCLC 37813710. Retrieved 2021-08-08.

- ^ Peter Gerhard, The Northern Frontier of New Spain (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982) p. 245

- ^ "History of Mexico - The State of Sinaloa". www.houstonculture.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2005-07-14.

- ^ Carton de Grammont, Hubert (1990). Los empresarios agrícolas y el Estado: Sinaloa 1893-1984 (in الإسبانية). Archived from the original on 2021-06-21. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Burian, Edward (2021-10-01). "The Geography and Landscapes of Northern Mexico". The Architecture and Cities of Northern Mexico from Independence to the Present (in الإنجليزية). University of Texas Press. pp. 6–10. doi:10.7560/771901-004. ISBN 978-1-4773-0722-9. Archived from the original on 2022-08-25. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ "Clima de Sinaloa". Cuéntame... Información por entidad. INEGI. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2009

- ^ "Censo Sinaloa 2020". Archived from the original on 2021-01-28. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةauto - ^ "En Sinaloa somos 3 026 943 habitantes: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Sinaloa" (in الإسبانية). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-08-25. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ "Esperanza de vida al nacimiento por entidad federativa según sexo, serie anual de 2010 a 2024".

- ^ "Mazatlán es un paraíso para canadienses y estadounidenses". 23 July 2022.

- ^ Aguilar, Gustavo (2006). "Inmigración griega y empresa agrícola en Sinaloa (1927-1971): éxitos y fracasos". Secuencia (in الإسبانية) (64): 145–185. doi:10.18234/secuencia.v0i64.955. ISSN 0186-0348. Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ "Panorama sociodemográfico de México". www.inegi.org.mx. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ "Indicador Trimestral de la Actividad Económica Estatal (ITAEE)". CODESIN | Sinaloa en Números (in الإسبانية المكسيكية). 2022-08-02. Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ Sandoval Cabrera, Seyka Verónica (2012). "Condiciones histórico-estructurales de los productores de hortalizas sinaloenses en la cadena de valor, 1900-2010". Región y sociedad (in الإسبانية). 24 (54): 231–259. ISSN 1870-3925.

- ^ "Sinaloa". SEDESOL Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Sinaloa. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2005. pp. 27, 29, 33. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/Productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/inter_censal/estados2015/702825079895.pdf. Retrieved on 26 April 2017. - ^ "Expide Congreso Bando Solemne para difundir que Rubén Rocha Moya es gobernador - H. Congreso del Estado de Sinaloa". H. Congreso del Estado de Sinaloa (in الإسبانية). Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ "Constitución Política del Estado de Sinaloa". Wayback Machine. 2015-05-01. Archived from the original on 2015-05-01. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ Lawrence Downes (13 August 2009). "In Los Angeles, Songs Without Borders". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ أ ب Simonett, Helena (2004). En Sinaloa nací: historia de la música de banda (First ed.). Mazatlán: Asociación de Gestores del Patrimonio Histórico y Cultural de Mazatlán. ISBN 970-93894-0-8. OCLC 55609923.

- ^ "6 Most Popular Sinaloan Dishes". Taste Atlas. Archived from the original on 2022-08-25. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ "Sinaloan cuisine, Mexican food crown jewel". The Mazatlan Post (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2018-07-19. Archived from the original on 2022-08-25. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ "Oh No, There Goes Tokyo Roll—Sinaloa Style Sushi Invades Los Angeles". Lamag - Culture, Food, Fashion, News & Los Angeles. August 2013. Archived from the original on 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ "Publicaciones periódicas en Sinaloa". Sistema de Información Cultural (in الإسبانية). Gobierno de Mexico. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Latin American & Mexican Online News". Research Guides. US: University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020.

- ^ "El juego de pelota de Mesoamérica". 16 September 2013.

- ^ "The Game". Mesoamerican Heritage Chapter of the Asociacion de Gestores del Patrimonio Historico y Cultural de Mazatlan. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Asociacion de Gestores del Patrimonio Historico y Cultural de Mazatlan. 2009

- ^ "Equipos de Sinaloa en Liga Mexicana del Pacífico tendrán aficionados en sus juegos". La Razón (in الإسبانية). 17 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ "Sinaloa Cartel Influence is Steadily Growing In Tijuana". Borderland Beat. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "Mexico's Sinaloa gang grows empire, defies crackdown". Reuters. 19 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

Sources

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Elephant Tree: Bursera microphylla, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- Asociación de Gestores del Patrimonio Histórico y Cultural de Mazatlán. 2009. The Mesoamerican Ballgame-Ulama

وصلات خارجية

- (بالإسپانية) Sinaloa state government

- (بالإسپانية) Towns, cities, and postal codes in Sinaloa

- The History of Indigenous Sinaloa

- PBS Frontline: The place Mexico's drug kingpins call home

- Bruce Springsteen song titled "Sinaloa Cowboys" about methamphetamine in Fresno county

- (بالإسپانية) Videomap of Culiacán

- PBS Frontline: The place Mexico's drug kingpins call home

- Todo sobre Sinaloa!

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإسبانية المكسيكية-language sources (es-mx)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing Mayo-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- سينالوا

- ولايات المكسيك

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1831

- تأسيسات 1831 في المكسيك