حرية الصحافة

| الصحافة |

|---|

|

| المجالات |

| الأصناف |

| الوقع الإجتماعي |

| وسائط إخبارية |

| الأدوار |

حرية الصحافة أو حرية الإعلام تعني حق نشر الحقائق والأفكار والآراء، دون تدخل من الحكومة، أو الجماعات الخاصة. وينطبق هذا الحق على الوسائل المطبوعة بما في ذلك الكتب والصحف والوسائل الإلكترونية التي تشمل المذياع والتلفاز.

نشأ الخلاف حول حرية الصحافة منذ أن بدأت الطباعة الحديثة في القرن الخامس عشر الميلادي لأن للكلمات قوة تأثير كبيرة على الناس. وتُعد قوة الإعلام اليوم أهم من أي وقت مضى بسبب كثرة وسائل الاتصال الحديثة. وتضع بعض الحكومات قيودًا على الصحافة لأنها تعتقد أنها تُستخدم لمعارضتها. وقد وضعت كثير من الحكومات الصحافة تحت سيطرتها لتخدم مصالحها. ويعمل معظم الناشرين والكُتاب على عكس ذلك من أجل تحقيق أكبر قدر ممكن من الحرية.

United Nations' 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference, and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers."[1]

This philosophy is usually accompanied by legislation ensuring various degrees of freedom of scientific research (known as scientific freedom), publishing, and the press. The depth to which these laws are entrenched in a country's legal system can go as far down as its constitution. The concept of freedom of speech is often covered by the same laws as freedom of the press, thereby giving equal treatment to spoken and published expression. Freedom of the press was formally established in Great Britain with the lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695. Sweden was the first country in the world to adopt freedom of the press into its constitution with the Freedom of the Press Act of 1766.[2]

العلاقة بالنشر الذاتي

Freedom of the press is not construed as an absence of interference by outside entities, such as a government or religious organization, but rather as a right for authors to have their works published by other people.[3] This idea was famously summarized by the 20th-century American journalist, A. J. Liebling, who wrote, "Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one". Freedom of the press gives the printer or publisher exclusive control over what the publisher chooses to publish, including the right to refuse to print anything for any reason.[3] If the author cannot reach a voluntary agreement with a publisher to produce the author's work, then the author must turn to self-publishing.

Status of press freedom worldwide

Beyond legal definitions, several non-governmental organizations use other criteria to judge the level of press freedom worldwide. Some create subjective lists, while others are based on quantitative data:

- Reporters Without Borders considers the number of journalists murdered, expelled, or harassed, the existence of a state monopoly on TV and radio, as well as the existence of censorship and self-censorship in the media, and the overall independence of media as well as the difficulties that foreign reporters may face to rank countries in levels of press freedom.

- The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) systematically tracks the number of journalists killed and imprisoned in reprisal for their work. It says it uses the tools of journalism to help journalists by tracking press freedom issues through independent research, fact-finding missions, and a network of foreign correspondents, including local working journalists in countries worldwide. CPJ shares information on breaking cases with other press freedom organizations worldwide through the International Freedom of Expression Exchange, a global network of more than 119 free expression organizations. CPJ also tracks impunity in cases of journalist murders. CPJ staff applies strict criteria for each case; researchers independently investigate and verify the circumstances behind each death or imprisonment.

- Freedom House studies the more general political and economic environments of each nation in order to determine whether relationships of dependence exist that limit in practice the level of press freedom that might exist in theory. Panels of experts assess the press freedom score and draft each country summary according to a weighted scoring system that analyzes the political, economic, legal and safety situation for journalists based on a 100-point scale. It then categorizes countries as having a free, partly free, or not free press.[4]

التقرير السنوي حول الصحفيين المقتولين وتعداد السجون

Each year, The Committee to Protect Journalists produces a comprehensive list of all working journalists killed in relation to their employment, including profiles of each deceased journalist within an exhaustive database, and an annual census of incarcerated journalists (as of midnight, December 1). The year 2017 reported record findings of jailed journalists, reaching 262. Turkey, China, and Egypt account for more than half of all global journalists jailed.[5]

As per a 2019 special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists, approximately 25 journalists were murdered on duty in 2019.[5] The figure is claimed to be the lowest since 2002, a year in which at least 21 journalists were killed while they were reporting from the field.[6] Meanwhile, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) reported 49 killings, the lowest since 2003, when almost 36 journalists were killed. Leading press watchdogs fear persisting danger for the life of journalists. The drop in the murder of in-field journalists came across during the "global attention on the issue of impunity in journalist murders", focusing on the assassination of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018 and Daphne Caruana Galizia, a Maltese blogger in October 2017.[7]

Every year, Reporters Without Borders establishes a subjective ranking of countries in terms of their freedom of the press. The Press Freedom Index list is based on responses to surveys sent to journalists that are members of partner organizations of the RWB, as well as related specialists such as researchers, jurists, and human rights activists. The survey asks questions about direct attacks on journalists and the media and other indirect sources of pressure against the free press, such as non-governmental groups.

In 2022, the eight countries with the most press freedom are, in order: Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Portugal, and Costa Rica. The ten countries with the least press freedom are, in order: North Korea, Eritrea, Iran, Turkmenistan, Myanmar, China, Vietnam, Cuba, Iraq, and Syria.[9]

حرية الصحافة

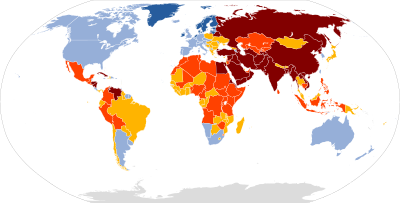

Freedom of the Press is a yearly report by the US-based non-profit organization Freedom House. It is known to subjectively measure the level of freedom and editorial independence that is enjoyed by the press in every nation and significant disputed territories around the world. Levels of freedom are scored on a scale from 1 (most free) to 100 (least free). Depending on the basics, the nations are then classified in three types: 1. "Free" 2. "Partly Free" 3. "Not Free".

الدول الديمقراطية

A free and independent press has been theorized to be a key mechanism of a functioning, healthy democracy.[11] In the absence of censorship, journalism exists as a watchdog of private and government action, providing information to maintain an informed citizenry of voters.[11] In this perspective, "government efforts to influence published or broadcasted news content, either via media control or by inducing self-censorship, represent a threat to the access of important and necessary information to the public and affect the quality of democracy".[12] An independent press "serves to increase political knowledge, participation, and voter turnout",[11] acting as an essential driver of civic participation.

الدول غير الديمقراطية

Turkey, China, Egypt, Eritrea, and Saudi Arabia accounted for 70% of all journalists that were imprisoned in 2018.[13] CPJ reported that "After China, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, the worst jailers are Eritrea, Vietnam, and Iran."[14]

According to Reporters Without Borders, more than a third of the world's people live in countries where there is no press freedom.[15] Overwhelmingly, these people live in countries where there is no system of democracy or where there are serious deficiencies in the democratic process.[16]

Freedom of the press is an extremely problematic problem/concept for most non-democratic systems of government since, in the modern age, strict control of access to information is critical to the existence of most non-democratic governments and their associated control systems and security apparatus. To this end, most non-democratic societies employ state-run news organizations to promote the propaganda critical to maintaining an existing political power base and suppress (often very brutally, through the use of police, military, or intelligence agencies) any significant attempts by the media or individual journalists to challenge the approved "government line" on contentious issues. In such countries, journalists operating on the fringes of what is deemed to be acceptable will very often find themselves the subject of considerable intimidation by agents of the state. This can range from simple threats to their professional careers (firing, professional blacklisting) to death threats, kidnapping, torture, and assassination.

- The Lira Baysetova case in Kazakhstan.[17]

- The Georgiy R. Gongadze case in Ukraine[18]

- In Nepal, Eritrea, and mainland China, journalists may spend years in jail simply for using the "wrong" word or photo.[15]

التاريخ

قيد الحكام وزعماء الكنيسة كتابة مواد معينة وتوزيعها حتى من قبل أن توجد الصحافة. وفي تلك الأيام، حينما كانت المواد كلها تُكتب باليد، كانت الكتب التي تُعد ضارة تُصادر أو تُخزن. ومنذ القرن الخامس الميلادي، فرضت الكنيسة الكاثوليكية الرومانية قيودًا على المواد التي تعدها معارضة لتعليمات الكنيسة.

وكان على المطابع أن تحصل على ترخيص من المحكمة، أو من الهيئة الدينية لأي مواد تريد نشرها. وقد قام الشاعر الإنجليزي، والكاتب السياسي جون ميلتون عام 1644م بنقد مثل هذا الترخيص في كُتيبه آريو باغيتيكا، وكانت هذه المقالة من أوائل المقالات التي ناقشت حرية الصحافة. وفي القرن الثامن عشر الميلادي حصل الصحفيون على حق الاطلاع على تقارير جلسات البرلمان ونشرها. وتمكن بذلك الناس العاديون من قراءة ما يُقال. وبحلول القرن التاسع عشر الميلادي، حصلت صحافة كثير من الدول على قدر كبير من الحرية.

أساءت بعض الجهات استخدام حرية الصحافة. ففي أواخر القرن التاسع عشر الميلادي، مثلاً، نشرت بعض صحف الولايات المتحدة مواد زائفة ومثيرة لتجذب القراء، وقد فضل بعض الناس أن تُوقف النظم الحكومية مثل هذه التصرفات.

وفي أوائل القرن العشرين، كانت معظم الصحافة الحرة قد نضجت بحيث تحملت مسؤوليتها تجاه الجمهور، وأصبح الصحفيون والعاملون في مجالات الإعلام الأخرى أكثر اهتمامًا ووعيًا بمراجعة الحقائق، وإرسال الأخبار. وفي بعض البلاد، فقدت الصحافة مع ذلك حريتها. فمثلاً، حجر الفاشيون في إيطاليا والنازيون في ألمانيا، حرية الصحافة قبل الحرب العالمية الثانية وأثناءها، واستخدموا الصحافة لخدمة أغراضهم. وقد حكمت الدكتاتوريات المدنية أو العسكرية كثيرًا من الدول في السنوات التي أعقبت الحرب العالمية الثانية التي انتهت عام 1945م. وقد وضعت كل هذه الدول رقابة شديدة على الصحافة.

القانون

تمنح الدساتير الديمقراطية حرية الصحافة لتشجيع تبادل الأفكار. ويحتاج المواطنون في النظم الديمقراطية الغربية إلى المعلومات لتساعدهم على تقرير ما إذا كانوا يؤيدون أو لايؤيدون السياسات التي تتبناها حكوماتهم. وفي النظام الديمقراطي، تنطبق حرية الصحافة، ليس فقط على الأمور السياسية والاجتماعية، ولكن أيضًا على الأعمال التجارية، والأمور الثقافية والدينية والعلمية.

وتُقيد معظم الحكومات الديمقراطية حرية الصحافة في ثلاثة أنواع من القضايا. وفي مثل هذه القضايا، تعتقد هذه الحكومات أن حرية الصحافة قد تعرض الأفراد، والأمن القومي، أو الأخلاق الاجتماعية للخطر. وهذه القضايا هي:

1- قوانين ضد القذف والاعتداء على الخصوصية، فتحمي الأفراد من الكتابات التي قد تهدد سمعتهم، أو خصوصيتهم.

2- قوانين ضد الفتنة (إثارة الثورة) والخيانة لمنع نشر مواد تضر بأمن الدولة.

3-قوانين ضد أعمال منافية للآداب (كاللغة البذيئة) تهدف إلى حماية أخلاق الناس.

وحتى حين يكفل الدستور حرية الصحافة، فإن على الصحافة أن تنظم نفسها. ويتجنب الناشرون والمذيعون نشر مواد خارجة عن الآداب واللياقة، وأي أمر آخر قد يخدش حياء عدد كبير من القراء أو المشاهدين أو المستمعين، تطبيقًا لنظرية المسؤولية الاجتماعية في الإعلام.

وتفرض أشد القيود على الصحافة خلال أوقات الطوارئ الوطنية، وخاصة أوقات الحروب. فخلال الحرب العالمية الثانية (1939-1945م)، مثلاً، فرضت حكومات الدول المشتركة في الحرب حظرًا على نشر أي مواد من شأنها أن تتدخل في المجهود الحربي أو تضر بالأمن القومي.

وكانت أقسام الرقابة تتحقق من عدم ظهور مثل هذه المواد في الصحف أو الكتب أو الإذاعة.

وتختلف قيود الصحافة اختلافًا كبيرًا من بلد إلى آخر. ففي بريطانيا مثلاً، تقيِّد الصحافة نفسها عادة فيما تنشره عن بعض جوانب الحياة الخاصة لأعضاء العائلة المالكة. وفي إيطاليا، تفعل الصحافة ذلك بالنسبة للبابا.

وتحاول الحكومة الديمقراطية أحيانًا حظر تداول كتاب تعتقد أنه يخترق قوانين الأمن القومي. وقد تعترض الجماعات الدينية على كتاب أو فيلم يُعتقد أنه مسيء لها، وتحاول سحبه عن طريق الناشر أو الموزع.

وتفرض حكومات كثير من الدول قيودًا شديدة شاملة على الصحافة. ولعدد من دول آسيا، وأمريكا اللاتينية، والشرق الأوسط، مجالس لمراقبة جميع المطبوعات المنشورة. ويعمل هؤلاء المراقبون على التأكد من أن الصحف والمطبوعات الأخرى تتبع توجيهات الحكومة، وتتفق مع السياسة الرسمية للدولة.

وفي الدكتاتورية الشيوعية، تتحكم الحكومة عادة في الصحافة، وفي وسائل الإعلام الإذاعية، عن طريق ملكية الصحف والإذاعة والتلفاز وإدارتها بنفسها. كما تعمل على التأكد من أن الصحافة تتبع سياسات الحزب.

حالة حرية الصحافة عالميا

مناطق مغلقة أمام المراسلين الأجانب

- الشيشان, روسيا[19]

- Jaffna, سريلانكا[20]

- مينامار (بورما)

- Jammu & Kashmir, India[21]

- پاپوا, اندونيسيا[22]

- Waziristan, پاكستان[23]

- Tibet, People's Republic of China[24]

آثار التقنيات الجديدة

منظمات لحرية الصحافة

- ARTICLE 19

- Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

- لجنة حماية الصحفيين

- مؤسسة الجبهة الإلكترونية

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange

- Internationale Medienhilfe

- معهد الصحافة الدولي

- OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

- مراسلون بلا حدود

- World Association of Newspapers

- World Press Freedom Committee

- Worldwide Governance Indicators

- Student Press Law Center

انظر أيضا

|

|

الهوامش

- ^ Nations, United. "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Nordin, Jonas (2023). The Swedish Freedom of the Press Ordinance of 1766: Background and Significance. Stockholm: The National Library of Sweden. ISBN 978-91-7000-474-2.

- ^ أ ب Powe, L. A. Scot (1992). The Fourth Estate and the Constitution: Freedom of the Press in America. University of California Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780520913165.

- ^ "Summit for Democracy: New Scorecards Highlight State of Freedom in Participating Countries". Freedom House (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2022-08-04. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ أ ب "Explore CPJ's database of attacks on the press". cpj.org. Archived from the original on 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ "Explore CPJ's database of attacks on the press". cpj.org. Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ "Number of journalists killed falls sharply as reprisal murders hit record low". Committee to Protect Journalists. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "2023 World Press Freedom Index". Reporters Without Borders. 2023.

- ^ "2022 World Press Freedom Index | Reporters Without Borders". RSF. Archived from the original on 2022-04-27. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- ^ "World Map of the Freedom of the Press Status". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت Ambrey, Christopher L.; Fleming, Christopher M.; Manning, Matthew; Smith, Christine (2015-08-04). "On the Confluence of Freedom of the Press, Control of Corruption and Societal Welfare". Social Indicators Research. 128 (2): 859–880. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1060-0. ISSN 0303-8300. S2CID 153582103.

- ^ Solis, Jonathan A.; Antenangeli, Leonardo (September 2017). "Corruption Is Bad News for a Free Press: Reassessing the Relationship Between Media Freedom and Corruption: Corruption Is Bad News for a Free Press". Social Science Quarterly. 98 (3): 1112–1137. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12438.

- ^ "Turkey leads the world in jailed journalists". The Economist. 16 January 2019. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Most Jailed Journalists? China, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Egypt Again Top Annual CPJ Report". VOA News. 11 December 2019. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Description: Reporters Without Borders". The Media Research Hub. Social Science Research Council. 2003. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ Freedom House (2005). "Press Freedom Table (Press Freedom vs. Democracy ranks)". Freedom of the Press 2005. UK: World Audit. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "Editor's daughter killed in mysterious circumstances" Archived 2019-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX), 2 July 2002

- ^ "Ukraine remembers slain reporter" Archived 2019-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 16 September 2004

- ^ "Do journalists have the right to work in Chechnya without accreditation?". Moscow Media Law and Policy Center. March 2000. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Sri Lanka - Advice for this Country". International News Safety Institute. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

the coastline and adjacent territorial sea of the Trincomalee, Mullaittivu, Jaffna, Kilinochchi and Mannar administrative districts in the north and east have been declared restricted zones by the Sri Lankan authorities and should be avoided.

- ^ "India praises McCain-Dalai Lama meeting". Washington, D.C.: WTOPews.com. July 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ "Indonesia: Police Abuse Endemic in Closed Area of Papua". Human Rights Watch. May 7, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-15. Retrieved September 6 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Landay, Jonathan S. (March 20, 2008). "Radical Islamists no longer welcome in Pakistani tribal areas". McClatchy Washington Bureau. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ "China criticizes McCain-Dalai Lama meeting". Washington, D.C.: WTOPews.com. July 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

المصادر

- Starr, Paul (2004). The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-08193-2.

- Gant, Scott (2007). We're All Journalists Now: The Transformation of the Press and Reshaping of the Law in the Internet Age. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-9926-4.

- الموسوعة المعرفية الشاملة

وصلات خارجية

- Risorse Etiche Publish and translate articles of independent journalists

- the ACTivist Magazine

- Banned Magazine, the journal of censorship and secrecy.

- News and Free Speech - Newspaper Index Blog

- Press Freedom

- OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

- MANA - the Media Alliance for New Activism

- IMH-Internationale Medienhilfe www.medienhilfe.org

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange- Monitors press freedom around the world

- IPS Inter Press Service Independent news on press freedom around the world

- The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press

- Reporters Without Borders

- Doha Center for Media Freedom

- World Press Freedom Committee

- Student Press Law Center

- Freedom Forum