ولادة قيصرية

| الولادة القيصرية Caesarean section | |

|---|---|

فريق طبي يجري عملية ولادة قيصرية.[1] | |

| أسماء أخرى | C-section, cesarean section, caesarean delivery |

| ICD-10-PCS | 10D00Z0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 74 |

| MeSH | D002585 |

| MedlinePlus | 002911 |

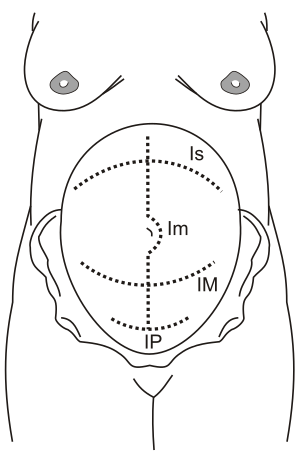

الولادة القيصرية (إنگليزية: Caesarean section)، هي عملية جراحية يتم فيها شق بطن الأم لولادة طفل أو أكثر، وغالباً ما تُجرى لأن الولادة المهبلية قد تعرض الطفل أو الأم للخطر.[2] تشمل أسباب اللجوء للولادة القيصرية الولادة المتعسرة، الحمل بتوأم، ارتفاع ضغط الدم عند الأم، الولادة المقعدية، ومشاكل في المشيمة أو الحبل السري.[2][3] تُجرى الولادة القيصرية بناءً على شكل حوض الأم أو تاريخ الولادة القيصرية السابقة.[2][3] من الممكن أن تلد الأم ولادة مهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية.[2] توصي منظمة الصحة العالمية بإجراء العملية القيصرية فقط عند الضرورة الطبية.[3][4] تُجرى بعض الولادات القيصرية بدون سبب طبي، عند الطلب من قبل شخص ما، عادة الأم.[2]

تستغرق الولادة القيصرية من 45 دقيقة إلى ساعة.[2] يمكن إجراؤها باستخدام التخدير النخاعي، حيث تكون المرأة مستيقظة، أو تحت التخدير العام.[2] تستخدم القسطرة البولية لتصريف المثانة، ثم يُنظف جلد البطن باستخدام مطهر.[2] عادة ما يُجرى شق بطول 15 سم تقريباً أسفل بطن الأم. [2] ثم يُفتح الرحم بشق ثانٍ ثم يُولد الطفل.[2] ثم تُغلق الشقوق بالمخيط.[2] عادة يمكن للمرأة البدء في إرضاع وليدها بمجرد خروجها من غرفة العمليات والإفاقة.[5] في كثير من الأحيان، يلزم قضاء عدة أيام في المستشفى للتعافي بشكل كافٍ قبل العودة إلى المنزل.[2]

تؤدي الولادات القيصرية إلى زيادة إجمالية طفيفة في النتائج السيئة في حالات الحمل منخفض الخطورة.[3] كما أنها تستغرق عادةً وقتًا أطول للتعافي عن الولادة المهبلية، حوالي ستة أسابيع.[2] تشمل المخاطر المتزايدة مشاكل في التنفس لدى الطفل وانصمام السائل السلوي ونزيف ما بعد الولادة لدى الأم.[3] توصي الدلائل الإرشادية المعمول بها بعدم اللجوء للولادة القيصرية قبل مرور 39 أسبوع من الحمل بدون سبب طبي.[6] لا يبدو أن طريقة الولادة لها تأثير على الوظيفة الجنسية لاحقاً.[7]

عام 2012، أُجريت حوالي 23 مليون عملية ولادة قيصرية على مستوى العالم.[8] اعتبرت الجمعية الدولية للرعاية الصحية أن معدل 10% و15% مثالي للولادة القيصرية.[4] وجدت بعض الأدلة أن رفع المعدل إلى 19% قد يؤدي إلى نتائج أفضل.[8] هناك أكثر من 45 دولة على مستوى العالم ذات معدلات ولادة قيصرية أقل من 7.5%، في حين أن أكثر من 50 دولة لديها معدلات أعلى من 27%.[8] تُبذل الجهود لتحسين عمليات الولادة القيصرية والحد من استخدامها.[8] عام 2017 في الولايات المتحدة، كان حوالي 32% من الولادات تُجرى بالجراحة القيصرية.[9] أُجريت الجراحة على الأقل منذ عام 715 قبل الميلاد بعد وفاة الأم، مع بقاء الطفل على قيد الحياة أحيانًا.[10] تعود توصيفات الأمهات اللائي بقين على قيد الحياة حتى عام 1500م، مع شواهد سابقة على العصور القديمة (بما في ذلك الرواية الملفقة لولادة يوليوس قيصر بعملية قيصرية، وهو أصل معروف للمصطلح).[10] مع إدخال المطهرات والتخدير في القرن التاسع عشر، أصبح بقاء كل من الأم والطفل، وبالتالي العملية الجراحية، أكثر شيوعًا بشكل ملحوظ.[10][11]

دواعي الولادة القيصرية

يوصى بالولادة القيصرية عندما تكون الولادة المهبلية تشكل خطرًا على الأم أو الطفل. تُجرى الولادات القيصرية أيضًا لأسباب شخصية واجتماعية متعلقة بطلب الأم في بعض البلدان.

الدواعي الطبية

مضاعفات المخاض والعوامل التي تزيد من المخاطر المرتبطة بالولادة المهبلية ما يلي:

- الولادة الغير طبيعية (الولادة المقعدية) أو وضع الجنين المعكوس.

- ولادةالمخاض لفترات طويلة أو الفشل في التقدم (المخاض المعوق، المعروف أيضًا باسم عسر الولادة).

- الضائقة الجنينية

- تدلي الحبل السري

- تمزق الرحم أو تزايد خطر حدوثه

- ارتفاع ضغط الدم لدى الأم، ما قبل تسمم الحمل،[12] أو تسمم الحمل.

- تسارع دقات القلب لدى الأم أو الطفل بعد تمزق السَّلَى (تمزق كيس الماء)

- مشاكل في المشيمة (المشيمة المنزاحة أو انفصال المشيمة المبكر أو المشيمة الملتصقة).

- فشل الطلق الاصطناعي.

- فشل الولادة بالأدوات (عن طريق الملقط أو جهاز شفط الجنين (في بعض الأحيان، تُجرى محاولة للتوليد باستخدام الملقط/الجفت، وإذا لم تنجح، فسيحتاج الطفل إلى الولادة القيصرية.)

- كبر حجم الوليد، 4.000> جرام (عملقة الجنين)

- تشوهات الحبل السري (الأوعية المتقدمة، متعددة الفصوص بما في ذلك المشيمة ثنائية الفصوص والمشيمة ذات الفصوص السرية، الإدراج الخيطي)

- حدوث مقدمات الارتعاج للمرأة الحامل.

- تعدد المواليد (حمل السيدة لأكثر من جنين داخل الرحم).

- إصابة الأم بالإيدز.

- إنتشار الهربس التناسلي في الثلاثة الأشهر الأخيرة من الحمل[13] (والذي يمكن أن يسبب عدوى للجنين إذا وُلد عن طريق المهبل)

- إجراء الأم عملية قيصرية كلاسيكية (طولية) سابقة.

- تمزق الرحم السابق.

- مشاكل سابقة في الشفاء من العجان (من ولادة سابقة أو مرض كرون)

- الرحم ثنائي القرن.

- حالات نادرة للولادة بعد وفاة الأم

أخرى:

- انخفاض خبرة المتعاملين مع حالة الولادة المقعدية. على الرغم من أن أطباء التوليد والقابلات مدربين على نطاق واسع على الإجراءات المناسبة للولادات المقعدية باستخدام نماذج محاكاة، هناك تجربة متناقصة مع الولادة المقعدية المهبلية الفعلية، مما قد يزيد من الخطر.[14]

الوقاية

من المتفق عليه عمومًا أن انتشار الولادة القيصرية أعلى مما هو مطلوب في العديد من البلدان، ويتم تشجيع الأطباء على خفض المعدل بنشاط، حيث أن معدل الولادة القيصرية الأعلى من 10-15% لا يرتبط بتخفيض معدلات وفيات الأمهات أو الرضع،[4] على الرغم من أن بعض الأدلة تدعم أن ارتفاع المعدل إلى 19% قد يؤدي إلى نتائج أفضل.[8]

بعض هذه الجهود هي: التأكيد على أن المرحلة الكامنة من المخاض ليس أمرًا غير طبيعي وليس مبررًا للولادة القيصرية؛ تعريف جديد لبدء المخاض النشط من توسع عنق الرحم بمقدار 4 سم إلى اتساع 6 سم؛ والسماح للنساء اللواتي سبق لهن الولادة بالضغط لمدة ساعتين على الأقل، مع 3 ساعات من الضغط على النساء اللواتي لم يسبق لهن الولادة، قبل توقف المخاض.[3] كما تخفض ممارسة [[تمرينات رياضية|التمرينات الرياضية] أثناء الحمل من المخاطر.[15]

المخاطر

تحدث النتائج السلبية في حالات الحمل منخفضة الخطورة في 8.6% من الولادات المهبلية و9.2% من الولادات القيصرية.[3]

على الأم

بالنسبة لحالات الحمل الأقل خطورة، فإن خطر الوفاة للولادة القيصرية هو 13 لكل 100000 مقابل الولادة المهبلية 3.5 لكل 100000 في العالم المتقدم.[3] بحسب خدمة الصحة الوطنية بالمملكة المتحدة، فإن خطر وفاة الأم في حالة الولادة القيصرية ثلاثة أضعاف خطر الولادة الطبيعية.[16]

في كندا، كان الاختلاف في معدلات الاعتلال أو الوفيات الخطيرة للأم (مثل السكتة القلبية أو الورم الدموي في الجرح أو استئصال الرحم) 1.8 حالة إضافية لكل 100.[17] لم يكن الاختلاف في وفيات الأمهات في المستشفى كبيراً.[17]

ترتبط العملية القيصرية بمخاطر التصاقات ما بعد الجراحة ، والفتق الجراحي (الذي قد يتطلب تصحيحًا جراحيًا)، وعدوى الجروح.[18] إذا أُجريت عملية قيصرية في حالة طارئة، فقد يزداد خطر الجراحة بسبب عدد من العوامل. قد لا تكون معدة المريضة فارغة، مما يزيد من خطر التخدير.[19] تشمل المخاطر الأخرى فقدان الدم الشديد (الذي قد يتطلب نقل الدم) وصداع ما بعد ثقب الجافية.[18]

تحدث التهابات الجروح بعد الولادة القيصرية بنسبة 3-15%.[20] وجود التهاب المشيمة والسلى والبدانة يهيئ المرأة للإصابة بعدوى في الموقع الجراحي.[20]

النساء اللواتي خضعن لعمليات قيصرية أكثر عرضة لمشاكل الحمل في وقت لاحق، والنساء اللواتي يرغبن في عدد أكبر من الولادات يجب ألا يطلبن عملية قيصرية اختيارية ما لم تكن هناك مؤشرات طبية للقيام بذلك. خطر المشيمة الملتصقة، وهي حالة قد تكون مهددة للحياة والتي من المرجح أن تتطور حيث خضعت المرأة لعملية قيصرية سابقة، تحدث بنسبة 0.13% بعد ولادة قيصرية، ولكنها تزيد إلى 2.13% بعد أربع ولادات ثم إلى 6.74% بعد ستة أو أكثر. إلى جانب هذا، هناك ارتفاع مماثل في مخاطر استئصال الرحم في حالات الطوارئ عند الولادة.[21]

يمكن للأمهات أن يعانين من زيادة في معدل الإصابة باكتئاب ما بعد الولادة، ويمكن أن يعانين من صدمة نفسية كبيرة واضطراب ما بعد الصدمة المرتبط بالولادة بعد التدخل التوليدي أثناء عملية الولادة.[22] عوامل مثل الألم في المرحلة الأولى من المخاض، والشعور بالعجز، والتدخل التوليدي الطارئ التدخلي مهمة في التطور اللاحق للقضايا النفسية المتعلقة بالمخاض والولادة.[22]

الحمل اللاحق

النساء اللواتي خضعن لعملية قيصرية لأي سبب من الأسباب أقل عرضة إلى حد ما للحمل مرة أخرى مقارنة بالنساء اللائي سبق لهن الولادة عن طريق المهبل فقط.[23]

النساء اللواتي خضعن لعملية قيصرية واحدة فقط من المرجح أن يعانين من مشاكل في ولادتهن الثانية.[3] في حالة الحمل بعد ولادة قيصرية سابقة تتم الولادة بخيارين رئيسيين:[بحاجة لمصدر]

- الولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية (VBAC)

- تكرار عملية الولادة القيصرية اختيارياً (ERCS)

يشكل كلا الخيارين مخاطر أعلى من الولادة المهبلية بدون ولادة قيصرية سابقة. تؤدي الولادة المهبلية بعد ولادة قيصرية (VBAC) إلى زيادة مخاطر تمزق الرحم (5 لكل 1000) ونقل الدم أو التهاب بطانة الرحم (10 لكل 1000) والوفاة المحيطة بالولادة للطفل (0.25 لكل 1000).[24]

علاوة على ذلك، فإن 20% إلى 40% من محاولات الولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية المخططة تنتهي بالعملية القيصرية، مع وجود مخاطر أكبر للمضاعفات في عملية الولادة القيصرية الطارئة مقارنةً بالولادة القيصرية الاختيارية المتكررة.[25][26] من جهة أخرى، تمنح الولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية اعتلال أقل للاهمات وتقلل من خطر حدوث مضاعفات في حالات الحمل المستقبلية مقارنةً بالولادة القيصرية الاختيارية المتكررة.[27]

الالتصاقات

هناك العديد من الخطوات التي يمكن اتخاذها أثناء العمليات في البطن أو الحوض لتقليل المضاعفات التي تحدث بعد العمليات، كحدوث الالتصاقات.

هذه التقنيات والمبادئ قد تتضمن:

- التعامل مع جميع النسج بعناية كبيرة

- استعمالات القفازات الخالية من البودرة

- اختيار الغرز والمواد الزرع بعناية

- التحكم بالنزيف

- إبقاء النسج رطبة

- منع حدوث الالتهابات

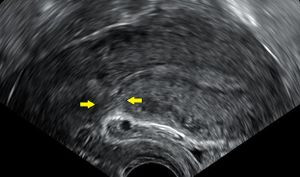

لكن بالرغم من هذه الإجراءات، الجراحة في البطن أو الحوض قد تؤدي إلى إصابات قد تسبب التصاقات. من أجل منع حدوث الالتصاقات بعد الجراحات في الحوض (النسائية) كاستئصال الرحم، استئصال أورام عضلة الرحم أو العمليات القيصرية، موانع الالتصاق يمكن وضعها أثناء العملية لتقليل خطر حدوث التصاقات بين الرحم والمبيض، الأمعاء الدقيقة، وتقريبا أي نسيج في البطن أو الحوض.

- العقم: والذي ممكن أن يحصل عندما تلف الالتصاقات نسج المبيض والأنابيب فتمنع الطريق الطبيعي لمرور البويضة من المبيض إلى الرحم. واحدة من كل خمس حالات عقم يقدر أن يكون سببها الالتصاقات.

ألم الحوض المزمن: والذي يمكن أن يحصل عند وجود الالتصاقات في الحوض. تقريبا 50% من حالات

- انسداد الأمعاء الدقيقة: اضطراب في الحركة المعوية الطبيعية، والذي يمكن أن يحصل عندما تلف أو تشد الالتصاقات قد تسبب مضاعفات مثل:

- ألم الحوض المزمن مرتبطة بوجود التصاقات.

- الالتصاقات الأمعاء الدقيقة.

على الطفل

إن الولادة التي ليس لها دواعي طبية (الاختيارية) قبل الأسبوع 39 من الحمل "تحمل مخاطر كبيرة على الطفل دون فائدة معروفة للأم". قد تصل وفيات الأطفال حديثي الولادة عند 37 أسبوعًا إلى 3 أضعاف العدد عند 40 أسبوعًا، وترتفع مقارنةً بـ 38 أسبوعًا من الحمل. ارتبطت هذه الولادات المبكرة بمزيد من الوفيات أثناء الطفولة ، مقارنةً بتلك التي تحدث عند 39 إلى 41 أسبوعًا (المدة الكاملة).[28] وجد الباحثون في دراسة ومراجعة أخرى العديد من الفوائد للمضي قدماً، ولكن لا توجد آثار ضارة على صحة الأمهات أو الأطفال.[28][29]

يقوم المجلس الأمريكي لأطباء النساء والتوليد وصانعي السياسات الطبية بمراجعة الدراسات البحثية واكتشاف المزيد من حالات الإنتن المشتبه بها أو المؤكدة، ونقص السكر في الدم، والحاجة إلى دعم الجهاز التنفسي، والحاجة إلى قبول المجلس الأمريكي لأطباء النساء والتوليد، والحاجة إلى العلاج في المستشفى > 4-5 أيام. في حالة العمليات القيصرية، كانت معدلات الوفاة التنفسية أعلى 14 مرة في ما قبل المخاض عند 37 أسبوعًا مقارنة مع 40 أسبوعًا من الحمل، و8.2 مرات أعلى في الولادة القيصرية قبل المخاض عند 38 أسبوعًا. في هذه المراجعة، لم تجد أي دراسات انخفاضًا في مراضة الأطفال حديثي الولادة بسبب الولادة غير المحددة طبيًا (الاختيارية) قبل 39 أسبوعًا.[28]

بالنسبة لحالات الحمل الصحية بتوأم حيث يتجه كلا التوأمين إلى أسفل، يوصى بتجربة الولادة المهبلية بين 37 و38 أسبوعًا.[30][31] لا تؤدي الولادة المهبلية، في هذه الحالة، إلى تفاقم وضع أي من الرضيعين مقارنةً بالولادة القيصرية.[31] هناك بعض الجدل حول أفضل طريقة للولادة حيث يكون التوأم الأول هو الرأس أولاً والثاني ليس كذلك، لكن معظم أطباء التوليد يوصون بالولادة الطبيعية ما لم تكن هناك أسباب أخرى لتجنب الولادة المهبلية.[31] عندما لا يكون رأس التوأم الأول لأسفل، يوصى غالبًا بإجراء عملية قيصرية.[31] بغض النظر عما إذا كانت ولادة التوأم تتم عن طريق الجراحة القيصرية أو عن طريق المهبل، فإن الأدبيات الطبية توصي بتوليد التوائم ثنائية المشيمة عند 38 أسبوعًا، والتوأم أحادي المشيمة (توأمان متماثلان يشتركان في المشيمة) بحلول 37 أسبوعًا بسبب زيادة خطر ولادة جنين ميت في التوائم أحادية المشيمة التي تبقى في الرحم بعد 37 أسبوعًا.[32][33] الإجماع هو أن الولادة المبكرة للتوائم أحادية المشيمة لها ما يبررها لأن خطر الإملاص للولادة بعد 37 أسبوعًا أعلى بكثير من المخاطر التي تشكلها ولادة التوائم أحادية المشيمة على المدى القريب (أي، 36-37 أسبوعًا).[34]

الإجماع بشأن التوائم أحادية السلى (توأمان متماثلان يتشاركان في الكيس السلوي)، وهو النوع الأكثر خطورة من التوائم، هو أنه يجب ولادتهما بعملية قيصرية في أو بعد فترة وجيزة من 32 أسبوعًا، لأن مخاطر وفاة أحد التوأمين داخل الرحم أو كليهما أعلى بعد هذا الحمل من خطر حدوث مضاعفات الخداج.[35][36][37]

في دراسة بحثية تم نشرها على نطاق واسع، قد يعاني الأطفال المنفردين المولودين قبل 39 أسبوعًا من مشاكل في النمو، بما في ذلك التعلم البطيء في القراءة والرياضيات.[38]

تتضمن المخاطر الأخرى:

- الرئة الرطبة: قد يحدث انحباس السوائل في الرئتين اذا لم يتم اخراجها نتيجة ضغط التقلصات أثناء الولادة.[39]

- احتمالية الولادة المبكرة والمضاعفات: قد يتم إجراء الولادة المبكرة عن غير قصد إذا كان حساب تاريخ الاستحقاق غير دقيق. وجدت إحدى الدراسات زيادة خطر حدوث مضاعفات إذا تم إجراء عملية قيصرية اختيارية متكررة حتى قبل أيام قليلة من الأسبوع الـ 39 الموصى به.[40]

- مخاطر أعلى لوفيات الرضع: في العمليات القيصرية التي أجريت مع عدم وجود مخاطر طبية محددة (مفردة على المدى الكامل في وضع الرأس لأسفل مع عدم وجود مضاعفات توليدية أو طبية أخرى)، تم الاستشهاد بخطر الوفاة في أول 28 يومًا من الحياة بمعدل 1.77 لكل 1000 ولادة حية بين النساء اللواتي خضعن لعملية قيصرية، مقارنة بمعدل 0.62 لكل 1000 من النساء اللواتي ولدن عن طريق المهبل.[41]

يبدو أن الولادة بعملية قيصرية مرتبطة أيضًا بنتائج صحية أسوأ في وقت لاحق من الحياة، بما في ذلك زيادة الوزن أو البدانة، ومشاكل في جهاز المناعة، وضعف الجهاز الهضمي.[42][43] ومع ذلك، وُجد أن الولادات القيصرية لا تؤثر على خطر إصابة حديثي الولادة بحساسية الطعام.[44] تتناقض هذه النتيجة مع دراسة سابقة تزعم أن الأطفال المولودين عن طريق الولادة القيصرية لديهم مستويات أقل من "البكتريا العصوانية" المرتبطة بحساسية الفول السوداني عند الرضع.[45]

التصنيف

تُصنف العمليات القيصرية بطرق مختلفة من خلال وجهات نظر مختلفة.[46] تتمثل إحدى طرق مناقشة جميع أنظمة التصنيف في تجميعها حسب تركيزها إما على إلحاح الإجراء (الأكثر شيوعًا)، أو خصائص الأم، أو كمجموعة بناءً على عوامل أخرى أقل شيوعًا في المناقشة.[46]

حسب إلحاح الإجراء

تقليدياً، تُصنف العمليات القيصرية على أنها إما جراحة اختيارية أو طارئة.[47]

يستخدم التصنيف للمساعدة في التواصل بين فريق التوليد والقبالة والتخدير لمناقشة أنسب طريقة للتخدير. يعتبر قرار إجراء تخدير عام أو تخدير موضعي (تخدير نخاعي أو فوق الجافية) أمرًا مهمًا ويستند إلى العديد من المؤشرات، بما في ذلك مدى إلحاح عملية الولادة بالإضافة إلى التاريخ الطبي والتوليدي للمرأة.[47] يكون التخدير الموضعي دائمًا أكثر أمانًا للمرأة والطفل، ولكن في بعض الأحيان يكون التخدير العام أكثر أمانًا لأحدهما أو لكليهما، ويعتبر تصنيف إلحاح الولادة مسألة مهمة تؤثر على هذا القرار.

يتم ترتيب العملية القيصرية المخططة (أو العملية القيصرية الاختيارية/المجدولة)، المرتبة مسبقًا، بشكل شائع للإشارات الطبية التي تطورت قبل أو أثناء الحمل، ويفضل بعد 39 أسبوعًا من الحمل. في المملكة المتحدة، يُصنف هذا على أنه قسم "من الدرجة الرابعة" (موعد الولادة المناسبة للأم أو طاقم المستشفى) أو قسم "الصف 3" (لا يوجد حل وسط للأم أو للجنين ولكن يلزم الولادة المبكرة). تُجرى العمليات القيصرية الطارئة في حالات الحمل التي تم التخطيط للولادة المهبلية فيه منذ البداية، لكن منذ ذلك الحين، تطور مؤشرالولادة القيصرية.

في المملكة المتحدة، تُصنف أيضًا على أنها من الدرجة الثانية (يلزم التوليد في غضون 90 دقيقة من القرار لكن لا يوجد تهديد مباشر على حياة المرأة أو الجنين) أو الدرجة الأولى (يلزم التوليد في غضون 30 دقيقة من القرار: تهديد فوري لحياة الجنين، حياة الأم أو الطفل أو كليهما.)[48]

يمكن إجراء العمليات القيصرية الاختيارية على أساس التوليد أو الاستدلال الطبي، أو بسبب عدم الإشارة طبيًا طلب الأم.[30] بين النساء في المملكة المتحدة والسويد وأستراليا، فضل حوالي 7% الولادة القيصرية كوسيلة للولادة. توصي كلية أطباء التوليد وأمراض النساء بالولادة المهبلية المخطط لها.[30] في الحالات التي لا توجد فيها مؤشرات طبية، يوصي المجلس الأمريكي لأطباء التوليد وأمراض النساء والكلية الملكية البريطانية لأطباء النساء والتوليد بالولادة المهبلية المخطط لها.[49] يوصي المعهد الوطني للتميز في الرعاية الصحية بأنه إذا تم تزويد المرأة بمعلومات عن مخاطر الولادة القيصرية المخطط لها وما زالت تصر على الإجراء، فيجب توفيرها.[30] إذا تم توفير ذلك، فيجب أن يتم ذلك في الأسبوع 39 من الحمل أو بعد ذلك.[49] لا يوجد دليل على أن الولادة القيصرية يمكن أن تقلل من انتقال عدوى ڤيروس التهاب الكبد الڤيروسي ب وج من الأم إلى الطفل.[50][51][52][53][54]

حسب اختيارات الأم

الولادة القيصرية بناء على طلب الأم

الولادة القيصرية بناء على طلب الأم] (CDMR) هي عملية قيصرية غير ضرورية طبيًا، حيث يُطلب إجراء ولادة عبر ولادة قيصرية من قبل المرأة الحامل على الرغم من عدم وجود علاج طبي يشير لإجراء الجراحة.[55] لم تجد المراجعات المنهجية أي دليل قوي حول تأثير العمليات القيصرية لأسباب غير طبية.[30][56] تشجع التوصيات على الاستشارة لتحديد أسباب الطلب، ومعالجة القلق والمعلومات لدى المرأة الحامل، وتشجيعها على الولادة المهبلية.[30][57]

أظهرت العمليات القيصرية الاختيارية في الأسبوع 38 في بعض الدراسات زيادة المضاعفات الصحية عند الوليد. لهذا السبب يوصي المؤتمر الأمريكي لأطباء النساء والتوليد والمعهد الوطني للتميز في الرعاية الصحية بعدم تحديد موعد الولادة القيصرية الاختيارية قبل 39 أسبوعًا من الحمل ما لم يكن هناك سبب طبي.[58][59][60] قد يُحدد موعد مبكر للعمليات القيصرية المخططة إذا كان هناك سبب طبي.[59]

بعد القيصرية السابقة

الأمهات اللاتي خضعن لعملية قيصرية من قبل هن أكثر عرضة لإجراء عملية قيصرية للحمل المستقبلي أكثر من الأمهات اللواتي لم يسبق لهن إجراء عملية قيصرية. هناك نقاش حول الظروف التي يجب أن تلد فيها المرأة عن طريق المهبل بعد ولادة قيصرية سابقة.

الولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية (VBAC) هي ولادة طفل عن طريق المهبل بعد ولادة طفل سابق بعملية قيصرية (جراحيًا).[61] بحسب الكلية الأمريكية لأطباء النساء والتوليد (ACOG)، يرتبط نجاح الولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية بانخفاض معدلات اعتلال الأمهات وانخفاض خطر حدوث مضاعفات في حالات الحمل المستقبلية.[62] وفقًا للجمعية الأمريكية للحمل، فإن 90% من النساء اللواتي خضعن لعمليات ولادة قيصرية هن مرشحات للولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية.[25] ما يقرب من 60-80% من النساء اللائي اخترن الولادة المهبلية بعد الولادة القيصرية سوف يلدن بنجاح عن طريق المهبل، وهو ما يمكن مقارنته بالمعدل الإجمالي للولادة المهبلية في الولايات المتحدة عام 2010.[25][26][63]

التوائم

للحالات الصحية للحمل بتوأم حيث يتجه كلا التوأمين إلى أسفل، يوصى بتجربة الولادة المهبلية في الفترة بين 37 و38 أسبوعً.[30][31] لا تؤدي الولادة المهبلية في هذه الحالة إلى تفاقم حالة أي من الرضيعين مقارنةً بالولادة القيصرية.[31] هناك جدل حول أفضل طريقة للولادة حيث يكون رأس التوأم الأول لأسفل والثاني ليس كذلك.[31] عندما لا يتجه التوأم الأول إلى نقطة بدء المخاض، يجب التوصية بإجراء عملية قيصرية.[31] على الرغم من أن التوأم الثاني عادة ما يكون معرضاً بشكل أكبر للمشكلات، إلا أنه من غير المعروف ما إذا كانت العملية القيصرية المخططة تؤثر على ذلك.[30] عام 2008، تشير التقديرات إلى أن 75% من حالات الحمل بتوأم في الولايات المتحدة قد أُجريت بعملية قيصرية.[64]

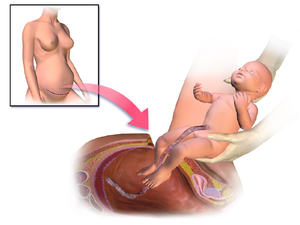

الولادة المقعدية

الولادة المقعدية هي خروج خروج مقعدة الطفل أولاً عند الولادة، حيث يخرج الطفل من الحوض وتكون الأرداف أو القدم أولاً بدلاً من خروج الرأس أولاً كما يحدث في الطبيعي. في حالة خروجه بالمؤخرة، تسمع أصوات قلب الجنين فوق السرة مباشرة.

عادة ما يولد الأطفال ورأسه أولاً. إذا كان الطفل في وضع آخر، فقد تكون الولادة معقدة. في "المجيء المقعدي"، يكون الطفل الذي لم يولد بعد في وضع الجالس حيث تكون مقعدته لأسفل بدلاً من رأسه. الأطفال الذين يولدون بهذا الوضع هم أكثر عرضة للأذى أثناء الولادة الطبيعية (المهبلية) أكثر من أولئك الذين يولدون بالرأس أولاً. على سبيل المثال، قد لا يحصل الطفل على كمية كافية من الأكسجين أثناء الولادة. قد يقلل الخضوع لعملية قيصرية مخططة هذه المشاكل. مراجعة تبحث في العملية القيصرية المخططة للمجيء المقعدي المفرد مع الولادة المهبلية المخطط لها، وتخلص إلى أنه على المدى القصير، كانت الولادات بعملية قيصرية مخططة أكثر أمانًا للأطفال من الولادات المهبلية. انخفض عدد الأطفال الذين ماتوا أو أصيبوا بجروح خطيرة عندما ولدوا بعملية قيصرية. كان هناك دليل مبدئي على أن الأطفال الذين ولدوا بعملية قيصرية يعانون من مشاكل صحية أكثر في سن الثانية. تسببت الولادات القيصرية في بعض المشاكل قصيرة الأمد للأمهات مثل آلام البطن. كما أن لها بعض الفوائد، مثل تقليل سلس البول وتقليل ألم العجان.[65]

يمثل المجيء المقعدي بعض المخاطر على الطفل أثناء عملية الولادة، وطريقة الولادة (المهبلية مقابل الولادة القيصرية) مثيرة للجدل في مجالات التوليد والقبالة.

على الرغم من أن الولادة المهبلية ممكنة للطفل المقعدي، إلا أن بعض العوامل الجنينية والأمومية تؤثر على سلامة الولادة المقعدية المهبلية. يولد غالبية الأطفال المقعدين المولودين في الولايات المتحدة والمملكة المتحدة بعملية قيصرية حيث أظهرت الدراسات زيادة مخاطر المراضة والوفيات عند الولادة المقعدية المهبلية، كما ينصح معظم أطباء التوليد بعدم الولادة المقعدية المهبلية المخطط لها لهذا السبب. نتيجة لانخفاض عدد الولادات المقعدية المهبلية الفعلية، يتعرض أطباء التوليد والقابلات لخطر فقدان المهارات في هذه المهارة المهمة. يخضع جميع المشاركين في تقديم رعاية التوليد والقبالة في المملكة المتحدة لتدريب إلزامي في إجراء عمليات الولادة المقعدية في بيئة المحاكاة (باستخدام أحواض وعارضات أزياء للسماح بممارسة هذه المهارة المهمة) ويتم تنفيذ هذا التدريب بانتظام للحفاظ على المهارات حتى تاريخ.

شق الرحم الإنعاشي

بضع الرحم الإنعاشي، المعروف أيضًا باسم الولادة القيصرية قبل الوفاة، هي عملية قيصرية طارئة يتم إجراؤها في حالة توقف قلب الأم للمساعدة في إنعاشها عن طريق إزالة ضغط الأبهر الأجوف الناتجة عن الرحم الحملي. على عكس الأشكال الأخرى للولادة القيصرية، فإن رعاية الجنين هي أولوية ثانوية فقط، ويمكن إجراء العملية حتى قبل حد بقاء الجنين إذا تبين أنه مفيد للأم.

طرق أخرى، تتضمن تقنيات جراحية

هناك عدة أنواع من العمليات القيصرية. يكمن التمييز الهام بينهما في نوع الشق (الطولي أو العرضي) الذي يجرى للرحم، بصرف النظر عن الشق الموجود على الجلد: الغالبية العظمى من شقوق الجلد هي طريقة فوق العانة المستعرضة تُعرف باسم شق بفاننستيل ولكن لا توجد طريقة لمعرفة الندبة الجلدية إلى أي طريقة تم بها شق للرحم.

- تتضمن العملية القيصرية الكلاسيكية شقاً طولياً في خط الوسط على الرحم مما يسمح بمساحة أكبر لولادة الطفل.

تُجرى الولادة القيصرية في فترات الحمل المبكرة جدًا حيث يكون الجزء السفلي من الرحم غير متكون لأنه أكثر أمانًا في هذه الحالة للطفل: ولكن نادرًا ما تُجرى في فترات غير مبكرة من الحمل، حيث تكون الأم أكثر عرضة للمضاعفات من انخفاض شق الرحم المستعرض. يُنصح أي امرأة تقوم بولادة قيصرية أن تجري الشق في نفس المكان الذي أجرته في الحمل السابق لأن الشق العمودي يكون أكثر عرضة للتمزق في المخاض من الشق المستعرض.

- الولادة القيصرية أسفل الرحم هو الإجراء الأكثر شيوعًا اليوم؛ حيث يُجرى قطع عرضي فوق حافة المثانة. ينتج عنه فقدان الدم أقل ويقلل من المضاعفات المبكرة والمتأخرة للأم، فضلاً عن السماح لها بالتفكير في الولادة المهبلية في الحمل التالي.

- شق الرحم القيصري، هو عملية قيصرية يتبعها استئصال الرحم. يمكن القيام بذلك في حالات النزيف المستعصي أو عندما يتعذر فصل المشيمة عن الرحم.

EXIT procedure هو إجراء جراحي متخصص يستخدم لتوليد الأطفال الذين يعانون من ضغط مجرى الهواء.

طريقة مسگاڤ لاداخ هي عملية قيصرية معدلة استخددمت في جميع أنحاء العالم تقريبًا منذ التسعينيات. وصفها مايكل ستارك، رئيس الأكاديمية الجراحية الأوروپية الجديدة، حين كان مديرًا لمستشفى مسگاڤ لاداخ العام في القدس. اقترحت الطريقة أثناء مؤتمر FIGO في مونتريال عام 1994[66] ثم نشرتها جامعة أوپسالا بالسويد، في أكثر من 100 دولة. تعتمد هذه الطريقة على مبادئ أضيق الحدود. يتم فحص جميع الخطوات في العمليات القيصرية قيد الاستخدام، وحللها لضرورتها، وإذا وجدت ضرورية، لطريقة أدائها الأمثل. بالنسبة لشق البطن، استخدم شق جويل كوهين المعدل وقارن الهياكل البطنية الطولية بالأوتار الموجودة على الآلات الموسيقية. نظرًا لأن الأوعية الدموية والعضلات لها تأثير جانبي، فمن الممكن شدها بدلاً من قطعها. يُفتح الغشاء البريتوني عن طريق الشد المتكرر، ولا تستخدم مسحات من البطن، ويغلق الرحم في طبقة واحدة بإبرة كبيرة لتقليل كمية الجسم الغريب قدر الإمكان، وتبقى الطبقات البريتونية غير مخيطة والبطن مغلق بطبقتين فقط. تتعافى النساء اللواتي يخضعن لهذه العملية بسرعة ويمكنهن رعاية الأطفال حديثي الولادة بعد الجراحة بفترة وجيزة. هناك العديد من المنشورات التي توضح مزايا طرق الولادة القيصرية التقليدية. هناك أيضًا خطر متزايد للإصابة بالمشيمة المفاجئة وتمزق الرحم في حالات الحمل اللاحقة للنساء اللواتي خضعن لهذه الطريقة في الولادات السابقة.[67][68]

منذ عام 2015، أقرت منظمة الصحة العالمية تصنيف روبسون كوسيلة شاملة لمقارنة معدلات الولادة بين البيئات المختلفة، بهدف السماح بمقارنة أكثر دقة لمعدلات الولادة القيصرية.[69]

التقنية

تستخدم الوقاية المضادة للميكروبات قبل الشق.[70] يُشق الرحم، ويُمدد هذا الشق بضغط غير حاد على طول محور الرأس والذيل.[70] يولد الطفل ثم تزال المشيمة.[70] ثم يتخذ الجراح قرارًا بشأن جعل exteriorization الرحم.[70] يستخدم إغلاق الرحم أحادي الطبقة عندما لا ترغب الأم في الحمل مستقبلاً.[70] عندما يبلغ سمك النسيج تحت الجلد 2 سم أو أكثر، يقوم الجراح بخياطة الشق.[70] تشمل الممارسات غير المرغوبة تمدد عنق الرحم، تصريف أي سوائل تحت الجلد،[71] أو العلاج بالأكسجين التكميلي للوقاية من حدوث العدوى.[70]

يمكن إجراء الجراحة القيصرية بخياطة طبقة واحدة أو طبقتين من شق الرحم.[72] لوحظ أن إغلاق الطبقة الواحدة مقارنة بإغلاق الطبقة المزدوجة يؤدي إلى تقليل فقد الدم أثناء الجراحة. من غير المؤكد ما إذا كان هذا هو التأثير المباشر لتقنية الخياطة أو إذا كانت هناك عوامل أخرى مثل نوع وموقع شق البطن تساهم في تقليل فقد الدم.[73] يتضمن الإجراء القياسي إغلاق الصفاق. يتساءل البحث عما إذا كان هذا ضروريًا، حيث تشير بعض الدراسات إلى أن الإغلاق البريتوني مرتبط بوقت أطول للعملية والإقامة في المستشفى.[74] طريقة مسگاڤ لاداخ هي عملية جراحية تقنية قد يكون لها مضاعفات ثانوية أقل وشفاء أسرع، بسبب الإدخال في العضلات.[75]

التخدير

كلا من التخدير العام والتخدير الموضعي (النخاع الشوكي، فوق الجافية أو التخدير النخاعي وفوق الجافية) مقبولان للاستخدام أثناء عملية قيصرية. لا تظهر الأدلة فرقاً بين التخدير الموضعي والتخدير العام فيما يتعلق بالنتائج الرئيسية في الأم أو الطفل.[76] Regional anaesthesia may be preferred as it allows the mother to be awake and interact immediately with her baby.[77] مقارنة بالتخدير العام، يكون التخدير الموضعي أفضل في الوقاية من الألم المستمر بعد الجراحة بعد 3-8 أشهر من الولادة القيصرية.[78] قد تشمل المزايا الأخرى للتخدير الموضعي عدم وجود مخاطر نموذجية للتخدير العام: الشفط الرئوي (الذي يتمتع بنسبة عالية نسبيًا لدى المرضى الذين يخضعون للتخدير في أواخر الحمل) لمحتويات المعدة والمريء التنبيب.[76] One trial found no difference in satisfaction when general anaesthesia was compared with either spinal anaesthesia.[76]

Regional anaesthesia is used in 95% of deliveries, with spinal and combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia being the most commonly used regional techniques in scheduled caesarean section.[79] Regional anaesthesia during caesarean section is different from the analgesia (pain relief) used in labor and vaginal delivery. The pain that is experienced because of surgery is greater than that of labor and therefore requires a more intense nerve block.

General anesthesia may be necessary because of specific risks to mother or child. Patients with heavy, uncontrolled bleeding may not tolerate the hemodynamic effects of regional anesthesia. General anesthesia is also preferred in very urgent cases, such as severe fetal distress, when there is no time to perform a regional anesthesia.

الوقاية من المضاعفات

Postpartum infection is one of the main causes of maternal death and may account for 10% of maternal deaths globally.[80][30][81] A caesarean section greatly increases the risk of infection and associated morbidity, estimated to be between 5 and 20 times as high, and routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infections was found by a meta-analysis to substantially reduce the incidence of febrile morbidity.[81] Infection can occur in around 8% of women who have caesareans,[30] largely endometritis, urinary tract infections and wound infections. The use of preventative antibiotics in women undergoing caesarean section decreased wound infection, endometritis, and serious infectious complications by about 65%.[81] Side effects and effect on the baby is unclear.[81]

Women who have caesareans can recognize the signs of fever that indicate the possibility of wound infection.[30] Taking antibiotics before skin incision rather than after cord clamping reduces the risk for the mother, without increasing adverse effects for the baby.[30][82] Moderate certainty evidence suggest that chlorhexidine gluconate as a skin preparation is slightly more effective in prevention surgical site infections than povodone iodine but further research is needed.[83]

Some doctors believe that during a caesarean section, mechanical cervical dilation with a finger or forceps will prevent the obstruction of blood and lochia drainage, and thereby benefit the mother by reducing the risk of death. The evidence اعتبارا من 2018[تحديث] neither supported nor refuted this practice for reducing postoperative morbidity, pending further large studies.[84]

Hypotension (low blood pressure) is common in women who have spinal anaesthesia; intravenous fluids such as crystalloids, or compressing the legs with bandages, stockings, or inflatable devices may help to reduce the risk of hypotension but the evidence is still uncertain about their effectiveness.[85]

التواصل بين الأم والمولود

The WHO and UNICEF recommend that infants born by Caesarean section should have skin-to-skin contact (SSC) as soon as the mother is alert and responsive. Immediate SSC following a spinal or epidural anesthetic is possible because the mother remains alert however, after a general anesthetic the father or other family member may provide SSC until the mother is able.[86]

It is known that during the hours of labor before a vaginal birth a woman's body begins to produce oxytocin which aids in the bonding process, and it is thought that SSC can trigger its production as well. Indeed, women have reported that they felt that SSC had helped them to feel close to and bond with their infant. A review of literature also found that immediate or early SSC increased the likelihood of successful breastfeeding and that newborns were found to cry less and relax quicker when they had SSC with their father as well.[86]

التعافي

It is common for women who undergo caesarean section to have reduced or absent bowel movements for hours to days. During this time, women may experience abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting. This usually resolves without treatment.[87] Poorly controlled pain following non-emergent caesarean section occurs in between 13% to 78% of women.[88] Immediately after a caesarean section, some complementary and alternative therapies (such as acupuncture, electromagnetic therapy and music therapy) may help to relieve pain.[89] Abdominal, wound and back pain can continue for months after a caesarean section. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful.[30] For the first couple of weeks after a caesarean, women should avoid lifting anything heavier than their baby. To minimize pain during breastfeeding, women should experiment with different breastfeeding holds including the football hold and side-lying hold.[90] Women who have had a caesarean are more likely to experience pain that interferes with their usual activities than women who have vaginal births, although by six months there is generally no longer a difference.[91] Pain during sexual intercourse is less likely than after vaginal birth; by six months there is no difference.[30]

There may be a somewhat higher incidence of postnatal depression in the first weeks after childbirth for women who have caesarean sections, but this difference does not persist.[30] Some women who have had caesarean sections, especially emergency caesareans, experience post-traumatic stress disorder.[30]

Those who undergoes caesarean section has 18.3% chance of chronic surgical pain at three months and 6.8% chance of surgical pain at 12 months.[92]

التواتر

Global rates of caesarean section are increasing.[20] It doubled from 2003 to 2018 to reach 21%, and is increasing annually by 4%. In southern Africa it is less than 5%; while the rate is almost 60% in some parts of Latin America.[93] The Canadian rate was 26% in 2005–2006.[94] Australia has a high caesarean section rate, at 31% in 2007.[95] At one time a rate of 10% to 15% was thought to be ideal;[4] a rate of 19% may result in better outcomes.[8] The World Health Organization officially withdrew its previous recommendation of a 15% C-section rate in June 2010. Their official statement read, "There is no empirical evidence for an optimum percentage. What matters most is that all women who need caesarean sections receive them."[96]

More than 50 nations have rates greater than 27%. Another 45 countries have rates less than 7.5%.[8] There are efforts to both improve access to and reduce the use of C-section.[8] Globally, 1% of all caesarean deliveries are carried out without medical need. Overall, the caesarean section rate was 25.7% for 2004–2008.[97][98]

There is no significant difference in caesarean rates when comparing midwife continuity care to conventional fragmented care.[99] More emergency caesareans—about 66%—are performed during the day rather than the night.[100]

The rate has risen to 46% in China and to levels of 25% and above in many Asian, European and Latin American countries.[101] In Brazil and Iran the caesarean section rate is greater than 40%.[102] Brazil has one of the highest caesarean section rates in the world, with rates in the public sector of 35–45%, and 80–90% in the private sector.[103]

أوروپا

Across Europe, there are differences between countries: in Italy the caesarean section rate is 40%, while in the Nordic countries it is 14%.[104] In the United Kingdom, in 2008, the rate was 24%.[105] In Ireland the rate was 26.1% in 2009.[106]

In Italy, the incidence of caesarean sections is particularly high, although it varies from region to region.[107] In Campania, 60% of 2008 births reportedly occurred via caesarean sections.[108] In the Rome region, the mean incidence is around 44%, but can reach as high as 85% in some private clinics.[109][110]

الولايات المتحدة

In the United States the rate of C-section is around 33%, varying from 23% to 40% depending on the state.[3] One of three women who gave birth in the US delivered by caesarean in 2011. In 2012, close to 23 million C-sections were carried out globally.[8]

With nearly 1.3 million stays, caesarean section was one of the most common procedures performed in U.S. hospitals in 2011. It was the second-most common procedure performed for people ages 18 to 44 years old.[111] Caesarean rates in the U.S. have risen considerably since 1996.[112] The rate has increased in the United States, to 33% of all births in 2012, up from 21% in 1996.[3] In 2010, the caesarean delivery rate was 32.8% of all births (a slight decrease from 2009's high of 32.9% of all births).[113] A study found that in 2011, women covered by private insurance were 11% more likely to have a caesarean section delivery than those covered by Medicaid.[114] The increase in use has not resulted in improved outcomes, resulting in the position that C-sections may be done too frequently.[3]

الشرق الأوسط

في 5 سبتمبر 2022، أعلنت السلطات المصرية عن ارتفاع نسبة الولادة القيصرية بشكل غير مسبوق، لتسجل رقماً قياسياً وتعتلي به الصدارة العالمية. وأكد الجهاز المركزي للتعبئة العامة والإحصاء أن نسبة الولادة القيصرية قد وصلت إلى 72% من إجمالي عمليات الولادة في مصر، مقابل 52% عام 2014.[115]

وعن أسباب زيادة نسبة الولادة القيصرية في مصر قال الدكتور عمرو حسن مقرر المجلس القومي للسكان السابق:

- وجود موروثات قديمة في السينما والدراما، أوضحت معاناة آلام الأم خلال ولادتها، مما يؤدي إلى طلب بعض السيدات إجراء الولادة القيصرية تجنبا لذلك المشهد.

- وجود قناعة بأن حقنة "الأبيدورال" أو كما يسمونها بـ"إبرة الظهر" قد تسبب الشلل.

- عدم ممارسة الحامل للرياضة، والتي لها دور كبير في توسيع الحوض وتقوية عضلات البطن لتسهيل عملية الولادة، حيث أن الابتعاد عنها يجعلها تشعر بآلام الظهر الناتجة عن ضعف فقراته وبالتالي تستعجل الولادة القيصرية للتخلص منها.

- عدم توافر العديد من الجوانب الخاصة بالخدمة الطبية اللازمة أثناء الولادة الطبيعية في بعض المستشفيات، وهو ما جعل هناك تخوفات ورهبة لدى العديد من أصحاب الطبقة الوسطى بالمجتمع من الدخول في الولادة الطبيعية وطلب القيصرية مسبقاً.

التاريخ

Historically, caesarean sections performed upon a live woman usually resulted in the death of the mother.[116] It was considered an extreme measure, performed only when the mother was already dead or considered to be beyond help. By way of comparison, see the resuscitative hysterotomy or perimortem caesarean section.

According to the ancient Chinese Records of the Grand Historian, Luzhong, a sixth-generation descendant of the mythical Yellow Emperor, had six sons, all born by "cutting open the body". The sixth son Jilian founded the House of Mi that ruled the State of Chu (ح. 1030–223 BC).[117]

The mother of Bindusara (born ح. 320 BC, ruled 298 – ح. 272 BC), the second Mauryan Samrat (emperor) of India, accidentally consumed poison and died when she was close to delivering him. Chanakya, Chandragupta's teacher and adviser, made up his mind that the baby should survive. He cut open the belly of the queen and took out the baby, thus saving the baby's life.[118]

An early account of caesarean section in Iran (Persia) is mentioned in the book of Shahnameh, written around 1000 AD, and relates to the birth of Rostam, the legendary hero of that country.[119][120] According to the Shahnameh, the Simurgh instructed Zal upon how to perform a caesarean section, thus saving Rudaba and the child Rostam. In Persian literature caeserean section is known as Rostamina (رستمینه).[121]

In the Irish mythological text the Ulster Cycle, the character Furbaide Ferbend is said to have been born by posthumous caesarean section, after his mother was murdered by his evil aunt Medb.

The Babylonian Talmud, an ancient Jewish religious text, mentions a procedure similar to the caesarean section. The procedure is termed yotzei dofen. It also discusses at length the permissibility of performing a c-section on a dying or dead mother.[118] There is also some basis for supposing that Jewish women regularly survived the operation in Roman times (as early as the 2nd century AD).[122]

Pliny the Elder theorized that Julius Caesar's name came from an ancestor who was born by caesarean section, but the truth of this is debated (see the discussion of the etymology of Caesar). Some stories involve Caesar himself being born from the procedure; this is almost certainly false, as Caesar's mother Aurelia Cotta lived until Caesar's mid-40s. The Ancient Roman caesarean section was first performed to remove a baby from the womb of a mother who died during childbirth, a practice sometimes called the Caesarean law.[123]

The Catalan saint Raymond Nonnatus (1204–1240) received his surname—from the Latin non-natus ("not born")—because he was born by caesarean section. His mother died while giving birth to him.[124]

There is some indirect evidence that the first caesarean section that was survived by both the mother and child was performed in Prague in 1337.[125][126] The mother was Beatrice of Bourbon, the second wife of the King of Bohemia John of Luxembourg. Beatrice gave birth to the king's son Wenceslaus I, later the duke of Luxembourg, Brabant, and Limburg, and who became the half brother of the later King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV.

In an account from the 1580s, Jakob Nufer, a veterinarian in Siegershausen, Switzerland, is supposed to have performed the operation on his wife after a prolonged labour, with her surviving. His wife allegedly bore five more children, including twins, and the baby delivered by caesarean section purportedly lived to the age of 77.[127][128][129]

For most of the time since the 16th century, the procedure had a high mortality rate. In Great Britain and Ireland, the mortality rate in 1865 was 85%. Key steps in reducing mortality were:

- Introduction of the transverse incision technique to minimize bleeding by Ferdinand Adolf Kehrer in 1881 is thought to be first modern CS performed.

- The introduction of uterine suturing by Max Sänger in 1882

- Modification by Hermann Johannes Pfannenstiel in 1900, see Pfannenstiel incision

- Extraperitoneal CS and then moving to low transverse incision (Krönig, 1912)[مطلوب توضيح]

- Adherence to principles of asepsis

- Anesthesia advances

- Blood transfusion

- Antibiotics

European travellers in the Great Lakes region of Africa during the 19th century observed caesarean sections being performed on a regular basis.[130] The expectant mother was normally anesthetized with alcohol, and herbal mixtures were used to encourage healing. From the well-developed nature of the procedures employed, European observers concluded they had been employed for some time.[130] Robert William Felkin provided a detailed description.[131][132] James Barry was the first European doctor to carry out a successful caesarean in Africa, while posted to Cape Town between 1817 and 1828.[133]

The first successful caesarean section to be performed in the United States took place in Mason County, Virginia (now Mason County, West Virginia), in 1794. The procedure was performed by Dr. Jesse Bennett on his wife Elizabeth.[134]

قيصر من تراسينا

The patron saint of caesarean section is Caesarius, a young deacon martyred at Terracina, who has replaced and Christianized the pagan figure of Caesar.[135] The martyr (Saint Cesareo in Italian) is invoked for the success of this surgical procedure, because it was considered the new "Christian Caesar" – as opposed to the "pagan Caesar" – in the Middle Ages it began to be invoked by pregnant women to wish a physiological birth, for the success of the expulsion of the baby from the uterus and, therefore, for their salvation and that of the unborn. The practice continues, in fact the martyr Caesarius is invoked by the future mothers who, due to health problems or that of the baby, must give birth to their child by caesarean section.[136]

المجتمع والثقافة

Speculations that the Roman dictator Julius Caesar was born by the method now known as C-section are false.[137] Although caesarean sections were performed in Roman times, no classical source records a mother surviving such a delivery.[138][139] As late as the 12th century, scholar and physician Maimonides expresses doubt over the possibility of a woman's surviving this procedure and again becoming pregnant.[140] The term has also been explained as deriving from the verb caedere, "to cut", with children delivered this way referred to as caesones. Pliny the Elder refers to a certain Julius Caesar (an ancestor of the famous Roman statesman) as ab utero caeso, "cut from the womb" giving this as an explanation for the cognomen "Caesar" which was then carried by his descendants.[138] Nonetheless, the false etymology has been widely repeated until recently. For example, the first (1888) and second (1989) editions of the Oxford English Dictionary say that caesarean birth "was done in the case of Julius Cæsar".[141] More recent dictionaries are more diffident: the online edition of the OED (2021) mentions "the traditional belief that Julius Cæsar was delivered this way",[142] and Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (2003) says "from the legendary association of such a delivery with the Roman cognomen Caesar".[143]

The word 'Caesar', meaning either Julius Caesar or an emperor in general, is also borrowed or calqued in the name of the procedure in many other languages in Europe and beyond.[144]

حضور الأب

In many hospitals, the mother's partner is encouraged to attend the surgery to support her and share the experience.[145] The anaesthetist will usually lower the drape temporarily as the child is delivered so the parents can see their newborn.[بحاجة لمصدر]

المصادر

- ^ Fadhley, Salim (2014). "Caesarean section photography". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (2). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.006.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش "Pregnancy Labor and Birth". Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س "Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery". American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. March 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates" (PDF). 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Lauwers, Judith; Swisher, Anna (2010). Counseling the Nursing Mother: A Lactation Consultant's Guide (in الإنجليزية). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 274. ISBN 9781449619480. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-obstetricians-and-gynecologists/, retrieved on 1 August 2013

- ^ Yeniel, AO; Petri, E (January 2014). "Pregnancy, childbirth, and sexual function: perceptions and facts". International Urogynecology Journal. 25 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2118-7. PMID 23812577. S2CID 2638969.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Molina, G; Weiser, TG; Lipsitz, SR; Esquivel, MM; Uribe-Leitz, T; Azad, T; Shah, N; Semrau, K; Berry, WR; Gawande, AA; Haynes, AB (1 December 2015). "Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality". JAMA. 314 (21): 2263–70. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15553. PMID 26624825.

- ^ "Births: Provisional Data for 2017" (PDF). CDC. May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Moore, Michele C.; Costa, Caroline M. de (2004). Cesarean Section: Understanding and Celebrating Your Baby's Birth (in الإنجليزية). JHU Press. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9780801881336.

- ^ "The Truth About Julius Caesar and "Caesarean" Sections". 25 October 2013.

- ^ Turner R (1990). "Caesarean Section Rates, Reasons for Operations Vary Between Countries". Family Planning Perspectives. 22 (6): 281–2. doi:10.2307/2135690. JSTOR 2135690.

- ^ "Management of Genital Herpes in Pregnancy". ACOG. May 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Savage W (2007). "The rising Caesarean section rate: a loss of obstetric skill?". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 27 (4): 339–46. doi:10.1080/01443610701337916. PMID 17654182. S2CID 27545840.

- ^ Domenjoz, I; Kayser, B; Boulvain, M (October 2014). "Effect of physical activity during pregnancy on mode of delivery". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 211 (4): 401.e1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.030. PMID 24631706.

- ^ "Caesarean Section". NHS Direct. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- ^ أ ب Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, Kramer MS (2007). "Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (4): 455–60. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060870. PMC 1800583. PMID 17296957.

- ^ أ ب Pai, Madhukar (2000). "Medical Interventions: Caesarean Sections as a Case Study". Economic and Political Weekly. 35 (31): 2755–61.

- ^ "Why are Caesareans Done?". Gynaecworld. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- ^ أ ب ت Saeed, Khalid B M; Greene, Richard A; Corcoran, Paul; O'Neill, Sinéad M (11 January 2017). "Incidence of surgical site infection following caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol". BMJ Open. 7 (1): e013037. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013037. PMC 5253548. PMID 28077411.

- ^ Silver, Robert M.; Landon, Mark B.; Rouse, Dwight J.; Leveno, Kenneth J.; Spong, Catherine Y.; Thom, Elizabeth A.; Moawad, Atef H.; Caritis, Steve N.; Harper, Margaret; Wapner, Ronald J.; Sorokin, Yoram; Miodovnik, Menachem; Carpenter, Marshall; Peaceman, Alan M.; O'Sullivan, Mary J.; Sibai, Baha; Langer, Oded; Thorp, John M.; Ramin, Susan M.; Mercer, Brian M. (June 2006). "Maternal Morbidity Associated With Multiple Repeat Cesarean Deliveries". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 107 (6): 1226–1232. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84. PMID 16738145. S2CID 257455.

- ^ أ ب Olde E, van der Hart O, Kleber R, van Son M (January 2006). "Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a review". Clinical Psychology Review. 26 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.002. hdl:1874/16760. PMID 16176853. S2CID 22137961.

- ^ Gurol-Urganci, I.; Bou-Antoun, S.; Lim, C.P.; Cromwell, D.A.; Mahmood, T.A.; Templeton, A.; van der Meulen, J.H. (July 2013). "Impact of Caesarean section on subsequent fertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction. 28 (7): 1943–1952. doi:10.1093/humrep/det130. PMID 23644593.

- ^ "Birth After Previous Caesarean Birth, Green-top Guideline No. 45" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت "Vaginal Birth after Cesarean (VBAC)". American Pregnancy Association. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ أ ب Vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) guide Archived 12 مارس 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Mayo Clinic

- ^ American Congress of Obstetricians and, Gynecologists (Aug 2010). "ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 450–63. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. PMID 20664418.

- ^ أ ب ت "Elimination of Non-medically Indicated (Elective) Deliveries Before 39 Weeks Gestational Age" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Reddy, Uma M.; Bettegowda, Vani R.; Dias, Todd; Yamada-Kushnir, Tomoko; Ko, Chia-Wen; Willinger, Marian (2011). "Term Pregnancy: A Period of Heterogeneous Risk for Infant Mortality". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 117 (6): 1279–1287. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182179e28. PMC 5485902. PMID 21606738.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK) (2011). "Caesarean Section: NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 132". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. PMID 23285498. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Biswas, A; Su, LL; Mattar, C (Apr 2013). "Caesarean section for preterm birth and, breech presentation and twin pregnancies". Best Practice & Research: Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 27 (2): 209–19. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.09.002. PMID 23062593.

- ^ Lee YM (2012). "Delivery of twins". Seminars in Perinatology. 36 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2012.02.004. PMID 22713501.

- ^ Hack KE, Derks JB, Elias SG, Franx A, Roos EJ, Voerman SK, Bode CL, Koopman-Esseboom C, Visser GH (2008). "Increased perinatal mortality and morbidity in monochorionic versus dichorionic twin pregnancies: clinical implications of a large Dutch cohort study". BJOG. 115 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01556.x. PMID 17999692. S2CID 20983040.

- ^ Danon D, Sekar R, Hack KE, Fisk NM (2013). "Increased stillbirth in uncomplicated monochorionic twin pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (6): 1318–26. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318292766b. PMID 23812469. S2CID 5152813.

- ^ Pasquini L, Wimalasundera RC, Fichera A, Barigye O, Chappell L, Fisk NM (2006). "High perinatal survival in monoamniotic twins managed by prophylactic sulindac, intensive ultrasound surveillance, and Cesarean delivery at 32 weeks' gestation". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 28 (5): 681–7. doi:10.1002/uog.3811. PMID 17001748. S2CID 26098748.

- ^ Murata M, Ishii K, Kamitomo M, Murakoshi T, Takahashi Y, Sekino M, Kiyoshi K, Sago H, Yamamoto R, Kawaguchi H, Mitsuda N (2013). "Perinatal outcome and clinical features of monochorionic monoamniotic twin gestation". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 39 (5): 922–5. doi:10.1111/jog.12014. PMID 23510453. S2CID 40347063.

- ^ Baxi LV, Walsh CA (2010). "Monoamniotic twins in contemporary practice: a single-center study of perinatal outcome". Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 23 (6): 506–10. doi:10.3109/14767050903214590. PMID 19718582. S2CID 37447326.

- ^ "Academic Achievement Varies With Gestational Age Among Children Born at Term". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ Jha, Kanishk; Nassar, George N.; Makker, Kartikeya (2022), Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30726039, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537354/, retrieved on 2022-06-22

- ^ Study: Early Repeat C-Sections Puts Babies At Risk Archived 31 يناير 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Npr.org (8 January 2009). Retrieved on 26 July 2011.

- ^ "High infant mortality rate seen with elective c-section". Reuters Health—September 2006. Medicineonline.com. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Mueller, Noel T.; Zhang, Mingyu; Hoyo, Cathrine; Østbye, Truls; Benjamin-Neelon, Sara E. (August 2019). "Does cesarean delivery impact infant weight gain and adiposity over the first year of life?". International Journal of Obesity. 43 (8): 1549–1555. doi:10.1038/s41366-018-0239-2. ISSN 1476-5497. PMC 6476694. PMID 30349009.

- ^ C. Yuan et al. (2016), "Association Between Cesarean Birth and Risk of Obesity in Offspring in Childhood, Adolescence, and Early Adulthood", JAMA Pediatrics.

- ^ Currell, Anne; Koplin, Jennifer J.; Lowe, Adrian J.; Perrett, Kirsten P.; Ponsonby, Anne-Louise; Tang, Mimi L. K.; Dharmage, Shyamali C.; Peters, Rachel L. (2022-05-18). "Mode of Birth Is Not Associated With Food Allergy Risk in Infants". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice (in English). doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.03.031. ISSN 2213-2198. PMID 35597762. S2CID 248903112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Why C-Section Babies May Be at Higher Risk for a Food Allergy". Consumer Health News | HealthDay (in الإنجليزية). 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ أ ب Torloni, Maria Regina; Betran, Ana Pilar; Souza, Joao Paulo; Widmer, Mariana; Allen, Tomas; Gulmezoglu, Metin; Merialdi, Mario; Althabe, Fernando (20 January 2011). "Classifications for Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review". PLOS One. 6 (1): e14566. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...614566T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014566. PMC 3024323. PMID 21283801.

- ^ أ ب Lucas, DN; Yentis, SM; Kinsella, SM; Holdcroft, A; May, AE; Wee, M; Robinson, PN (Jul 2000). "Urgency of caesarean section: a new classification". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 93 (7): 346–50. doi:10.1177/014107680009300703. PMC 1298057. PMID 10928020.

- ^ Miheso, Johnstone; Burns, Sean. "Care of women undergoing emergency caesarean section" (PDF). NHS Choices. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ أ ب American College of Obstetricians and, Gynecologists (Apr 2013). "ACOG committee opinion no. 559: Cesarean delivery on maternal request". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (4): 904–7. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000428647.67925.d3. PMID 23635708.

- ^ Yang, Jin; Zeng, Xue-mei; Men, Ya-lin; Zhao, Lian-san (2008). "Elective caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus – a systematic review". Virology Journal. 5 (1): 100. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-100. PMC 2535601. PMID 18755018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Borgia, Guglielmo (2012). "Hepatitis B in pregnancy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (34): 4677–83. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i34.4677. PMC 3442205. PMID 23002336.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hu, Yali; Chen, Jie; Wen, Jian; Xu, Chenyu; Zhang, Shu; Xu, Biyun; Zhou, Yi-Hua (24 May 2013). "Effect of elective cesarean section on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 13 (1): 119. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-119. PMC 3664615. PMID 23706093.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ McIntyre, Paul G; Tosh, Karen; McGuire, William (18 October 2006). "Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to infant hepatitis C virus transmission". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (4): CD005546. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005546.pub2. PMC 8895451. PMID 17054264.

- ^ European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network (December 2005). "A Significant Sex—but Not Elective Cesarean Section—Effect on Mother‐to‐Child Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 192 (11): 1872–1879. doi:10.1086/497695. PMID 16267757.

- ^ NIH (2006). "State-of-the-Science Conference Statement. Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request" (PDF). Obstetrics & Gynecology. 107 (6): 1386–97. doi:10.1097/00006250-200606000-00027. PMID 16738168. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ Lavender, T; Hofmeyr, GJ; Neilson, JP; Kingdon, C; Gyte, GM (14 March 2012). "Caesarean section for non-medical reasons at term". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD004660. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004660.pub3. PMC 4171389. PMID 22419296.

- ^ "Elective Surgery and Patient Choice – ACOG". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ Glavind, Julie; Uldbjerg, Niels (April 2015). "Elective cesarean delivery at 38 and 39 weeks". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 27 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1097/gco.0000000000000158. PMID 25689238. S2CID 32050828.

- ^ أ ب "Caesarean section | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Committee Opinion No. 559". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (4): 904–907. April 2013. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000428647.67925.d3. PMID 23635708.

- ^ Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) – Overview Archived 30 ديسمبر 2009 at the Wayback Machine, WebMD

- ^ American College of Obstetricians and, Gynecologists (Aug 2010). "ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 450–63. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. PMID 20664418.

- ^ "NCHS Data Brief: Recent Trends in Cesarean Delivery in the United States Products". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Lee HC, Gould JB, Boscardin WJ, El-Sayed YY, Blumenfeld YJ (2011). "Trends in cesarean delivery for twin births in the United States: 1995–2008". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 118 (5): 1095–101. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182318651. PMC 3202294. PMID 22015878.

- ^ Hofmeyr, G Justus; Hannah, Mary; Lawrie, Theresa A (21 July 2015). "Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (7): CD000166. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000166.pub2. PMC 6505736. PMID 26196961.

- ^ Stark M. Technique of cesarean section: Misgav Ladach method. In: Popkin DR, Peddle LJ (eds): Women's Health Today. Perspectives on current research and clinical practice. Proceedings of the XIV World Congress of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Montreal. Parthenon Publishing group, New York, 81–5

- ^ Nabhan AF (2008). "Long-term outcomes of two different surgical techniques for cesarean". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 100 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.07.011. PMID 17904561. S2CID 5847957.

- ^ Hudić I, Bujold E, Fatušić Z, Skokić F, Latifagić A, Kapidžić M, Fatušić J (2012). "The Misgav-Ladach method of cesarean section: a step forward in operative technique in obstetrics". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 286 (5): 1141–6. doi:10.1007/s00404-012-2448-6. PMID 22752598. S2CID 809690.

- ^ World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme, 10 April 2015 (2015). "WHO Statement on caesarean section rates". Reprod Health Matters. 23 (45): 149–50. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2015.07.007. hdl:11343/249912. PMID 26278843. S2CID 40829330.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Dahlke, Joshua D.; Mendez-Figueroa, Hector; Rouse, Dwight J.; Berghella, Vincenzo; Baxter, Jason K.; Chauhan, Suneet P. (October 2013). "Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 209 (4): 294–306. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.043. PMID 23467047.

- ^ Gates, Simon; Anderson, Elizabeth R. (2013-12-13). "Wound drainage for caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD004549. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004549.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 24338262.

- ^ Stark M, Chavkin Y, Kupfersztain C, Guedj P, Finkel AR (March 1995). "Evaluation of combinations of procedures in cesarean section". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 48 (3): 273–6. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(94)02306-J. PMID 7781869. S2CID 72559269.

- ^ Dodd, Jodie M; Anderson, Elizabeth R; Gates, Simon; Grivell, Rosalie M (22 July 2014). "Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD004732. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004732.pub3. PMID 25048608.

- ^ Bamigboye, AA; Hofmeyr, GJ (11 August 2014). "Closure versus non-closure of the peritoneum at caesarean section: short- and long-term outcomes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD000163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000163.pub2. PMC 4448220. PMID 25110856.

- ^ Holmgren, G; Sjöholm, L; Stark, M (August 1999). "The Misgav Ladach method for cesarean section: method description". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 78 (7): 615–21. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780709.x. PMID 10422908. S2CID 25845500.

- ^ أ ب ت Afolabi BB, Lesi FE (2012). "Regional versus general anaesthesia for Caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD004350. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004350.pub3. PMID 23076903.

- ^ Hawkins JL, Koonin LM, Palmer SK, Gibbs CP (1997). "Anesthesia-related deaths during obstetric delivery in the United States, 1979–1990". Anesthesiology. 86 (2): 277–84. doi:10.1097/00000542-199702000-00002. PMID 9054245. S2CID 21467445.

- ^ Weinstein, Erica J; Levene, Jacob L; Cohen, Marc S; Andreae, Doerthe A; Chao, Jerry Y; Johnson, Matthew; Hall, Charles B; Andreae, Michael H (21 June 2018). "Local anaesthetics and regional anaesthesia versus conventional analgesia for preventing persistent postoperative pain in adults and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (2): CD007105. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007105.pub4. PMC 6377212. PMID 29926477.

- ^ Bucklin BA, Hawkins JL, Anderson JR, Ullrich FA (2005). "Obstetric anesthesia workforce survey: twenty-year update". Anesthesiology. 103 (3): 645–53. doi:10.1097/00000542-200509000-00030. PMID 16129992.

- ^ Kassebaum, NJ; Bertozzi-Villa, A; Coggeshall, MS; Shackelford, KA; Steiner, C; et al. (2 May 2014). "Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 384 (9947): 980–1004. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. PMC 4255481. PMID 24797575.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Smaill, Fiona M; Grivell, Rosalie M (28 October 2014). "Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD007482. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3. PMC 4007637. PMID 25350672.

- ^ Mackeen, A. Dhanya; Packard, Roger E; Ota, Erika; Berghella, Vincenzo; Baxter, Jason K; Mackeen, A. Dhanya (2014). "Timing of intravenous prophylactic antibiotics for preventing postpartum infectious morbidity in women undergoing cesarean delivery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD009516. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009516.pub2. PMID 25479008.

- ^ Hadiati, Diah R.; Hakimi, Mohammad; Nurdiati, Detty S.; Masuzawa, Yuko; da Silva Lopes, Katharina; Ota, Erika (25 June 2020). "Skin preparation for preventing infection following caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD007462. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007462.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7386833. PMID 32580252.

- ^ Liabsuetrakul, Tippawan; Peeyananjarassri, Krantarat (10 August 2018). "Mechanical dilatation of the cervix during elective caesarean section before the onset of labour for reducing postoperative morbidity". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (11): CD008019. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008019.pub3. PMC 6513223. PMID 30096215.

- ^ Chooi, C; Cox, JJ; Lumb, RS; Middleton, P; Chemali, M; Emmett, RS; Simmons, SW; Cyna, AM (1 July 2020). "Techniques for preventing hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (7): CD002251. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002251.pub4. PMC 7387232. PMID 32619039.

- ^ أ ب Stevens, J.; Schmied, V.; Burns, E.; Dahlen, H. (2014). "Immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact after a Caesarean section: a review of the literature". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 10 (4): 456–473. doi:10.1111/mcn.12128. PMC 6860199. PMID 24720501.

- ^ Pereira Gomes Morais, Edna; Riera, Rachel; Porfírio, Gustavo JM; Macedo, Cristiane R; Sarmento Vasconcelos, Vivian; de Souza Pedrosa, Alexsandra; Torloni, Maria R (17 October 2016). "Chewing gum for enhancing early recovery of bowel function after caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10): CD011562. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011562.pub2. PMC 6472604. PMID 27747876.

- ^ Yang, Michael M H; Hartley, Rebecca L; Leung, Alexander A; Ronksley, Paul E; Jetté, Nathalie; Casha, Steven; Riva-Cambrin, Jay (1 April 2019). "Preoperative predictors of poor acute postoperative pain control: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 9 (4): e025091. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025091. PMC 6500309. PMID 30940757.

- ^ Zimpel, SA; Torloni, MR; Porfírio, GJ; Flumignan, RL; da Silva, EM (1 September 2020). "Complementary and alternative therapies for post-caesarean pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD011216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011216.pub2. PMID 32871021. S2CID 221466152.

- ^ "C-section recovery: What to expect". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Lydon-Rochelle, MT; Holt, VL; Martin, DP (July 2001). "Delivery method and self-reported postpartum general health status among primiparous women". Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 15 (3): 232–40. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00345.x. PMID 11489150.

- ^ Jin J, Peng L, Chen Q, Zhang D, Ren L, Qin P, Min S (October 2016). "Prevalence and risk factors for chronic pain following cesarean section: a prospective study". BMC Anesthesiology. 16 (1): 99. doi:10.1186/s12871-016-0270-6. PMC 5069795. PMID 27756207.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Stemming the global caesarean section epidemic". The Lancet. 13 October 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "C-section rate in Canada continues upward trend". Canada.com. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014.

- ^ "To push or not to push? It's a woman's right to decide". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 يناير 2011. Archived from the original on 30 أغسطس 2011.

- ^ "Should there be a limit on Caesareans?". BBC News. 30 يونيو 2010. Archived from the original on 20 يوليو 2010.

- ^ "WHO | Global survey on maternal and perinatal health". Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Souza, JP; Gülmezoglu, AM; Lumbiganon, P; Laopaiboon, M; Carroli, G; Fawole, B; Ruyan, P (10 November 2010). "Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004–2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health". BMC Medicine. 8 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-71. PMC 2993644. PMID 21067593.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hodnett ED; Hodnett, Ellen (2000). Hodnett, Ellen (ed.). "Continuity of caregivers for care during pregnancy and childbirth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000062. PMID 10796108.

Hodnett ED; Henderson, Sonja (2008). Henderson, Sonja (ed.). "WITHDRAWN: Continuity of caregivers for care during pregnancy and childbirth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000062.pub2. PMID 18843605. - ^ Goldstick O, Weissman A, Drugan A (2003). "The circadian rhythm of "urgent" operative deliveries". Israel Medical Association Journal. 5 (8): 564–6. PMID 12929294.

- ^ "C-section rates around globe at 'epidemic' levels". AP / NBC News. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ "More evidence for a link between Caesarean sections and obesity". The Economist. 11 October 2017.

- ^ Ramires de Jesus, G; Ramires de Jesus, N; Peixoto-Filho, FM; Lobato, G (April 2015). "Caesarean rates in Brazil: what is involved?". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 122 (5): 606–9. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13119. PMID 25327984. S2CID 43551235.

- ^ "Women can choose Caesarean birth". BBC News. 23 نوفمبر 2011. Archived from the original on 19 أغسطس 2012.

- ^ "Focus on: caesarean section—NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement". Institute.nhs.uk. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ "Caesarean Section Rates Royal College of Physicians of Ireland". Rcpi.ie. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012.

- ^ "La clinica dei record: 9 neonati su 10 nati con il parto cesareo". Corriere della Sera. 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Sagliocco denuncia boom di parti cesarei in Campania". Pupia.tv. 31 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Cesarei, alla Mater Dei il record". Tgcom.mediaset.it. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Stocks C. Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #165. October 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. "Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011 – Statistical Brief #165". Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013..

- ^ "Births: Preliminary Data for 2007" (PDF). National Center for Health Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Moore JE, Witt WP, Elixhauser A (أبريل 2014). "Complicating Conditions Associate With Childbirth, by Delivery Method and Payer, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #173. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 14 يوليو 2014. Retrieved 6 يونيو 2014.

- ^ "مصر.. ارتفاع عدد الولادات القيصرية بشكل غير مسبوق". سكاي نيوز. 2022-09-05. Retrieved 2022-09-05.

- ^ Shorter, E (1982). A History of Women's Bodies. Basic Books, Inc. Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 0465030297.

- ^ Sima Qian. "楚世家 (House of Chu)". Records of the Grand Historian (in الصينية). Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ أ ب Lurie S (2005). "The changing motives of cesarean section: from the ancient world to the twenty-first century". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 271 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1007/s00404-005-0724-4. PMID 15856269. S2CID 26690619.

- ^ Shahbazi, A. Shapur. "RUDABA". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 19 July 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Torpin R, Vafaie I (1961). "The birth of Rustam. An early account of cesarean section in Iran". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 81: 185–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)36323-2. PMID 13777540.

- ^ Wikipedia Rostam

- ^ Boss J (1961). "The Antiquity of Caesarean Section with Maternal Survival: The Jewish Tradition". Medical History. 5 (2): 117–31. doi:10.1017/S0025727300026089. PMC 1034600. PMID 16562221.

- ^ "The Truth About Julius Caesar and "Caesarean" Sections". Today I Found Out (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2013-10-25. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ "St. Raymond Nonnatus". Catholic Online. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- ^ Pařízek, A.; Drška, V.; Říhová, M. (Summer 2016). "Prague 1337, the first successful caesarean section in which both mother and child survived may have occurred in the court of John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia". Ceska Gynekologie. 81 (4): 321–330. ISSN 1210-7832. PMID 27882755.

- ^ Goeij, Hana de (23 November 2016). "A Breakthrough in C-Section History: Beatrice of Bourbon's Survival in 1337". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Appropriations, United States Congress House Committee on (1970). Hearings, Reports and Prints of the House Committee on Appropriations (in الإنجليزية). U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Henry, John (1991). "Doctors and Healers: Popular Culture and the Medical Profession". In Stephen Pumphrey; Paolo L. Rossi; Maurice Slawinski (eds.). Science, Culture, and Popular Belief in Renaissance Europe. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-7190-2925-2.

- ^ Sewell, Jane Eliot (1993), Cesarean Section: A Brief History, National Library on Medicine], https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/pdf/cesarean.pdf

- ^ أ ب "Cesarean Section – A Brief History: Part 2". U.S. National Institutes of Health. 25 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Ellwood, Robert S. (1993). Islands of the Dawn: The Story of Alternative Spirituality in New Zealand. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1487-8.

- ^ Dunn, P. M (1 May 1999). "Robert Felkin MD (1853–1926) and Caesarean delivery in Central Africa (1879)". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 80 (3): F250–F251. doi:10.1136/fn.80.3.F250. PMC 1720922. PMID 10212095.

- ^ Pain, Stephanie (6 March 2008). "The 'male' military surgeon who wasn't". NewScientist.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Woman's Ills". Time. 18 June 1951. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ Caesarius Diaconus, testi e illustrazioni di Giovanni Guida, [s.l.: s.n.], 2015

- ^ Pasero Roberta, Cesareo di Terracina, un santo poco conosciuto: è il protettore del parto cesareo, in "DiPiù", anno XIV, n° 48, 3 dicembre 2018.

- ^ Bad Medicine: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, by Christopher Wanjek, p. 5 (John Wiley & Sons, 2003)

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةvanDongen-2009 - ^ "could not survive the trauma of a Caesarean" Oxford Classical Dictionary, Third Edition, "Childbirth"

- ^ Commentary to Mishnah Bekhorot 8:2

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989 s.v. Cæsarean, 2

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, "most recently modified version published online March 2021" s.v. Cæsarean, 2

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2003), Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed.), Springfield, Massachusetts, USA: Merriam-Webster, ISBN 978-0-87779-809-5, https://archive.org/details/merriamwebstersc00merr_6

- ^ For a summary, of an article about the relevant historical and linguistic questions, see [1] Archived 6 يناير 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hugill, K; Kemp, I; Kingdon, C (April 2015). "Fathers' presence at caesarean section with general anaesthetic: evidence and debate". The Practising Midwife. 18 (4): 19–22. PMID 26328461.

وصلات خارجية

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Find more about ولادة قيصرية at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Database entry Q228036 on Wikidata | |

انظر أيضاً

- اليوم العالمي للولادات المبكرة

- توائم أحادية المشيمة

- ولادة في النعش

- الضائقة الجنينية

- حمل إضافي

- تحريض المخاض

- الولادة المنزلية

المصادر

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about ولادة قيصرية at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Database entry Q228036 on Wikidata | |

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- Articles with dead external links from June 2016

- CS1 الصينية-language sources (zh)

- Articles with dead external links from September 2017

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2022

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2018

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from January 2009

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2015

- جراحة التوليد

- ولادة الأطفال

- ولادة قيصرية

- RTT

- صحة المرأة