کيوستنديل

كيوستنديل

Кюстендил Kyustendil | |

|---|---|

بلدة | |

| |

| الإحداثيات: 42°17′N 22°41′E / 42.283°N 22.683°E | |

| البلد | بلغاريا |

| المحافظة (Oblast) | كيوستنديل |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة | Petar Paunov |

| المساحة | |

| • بلدة | 28٫72 كم² (11٫09 ميل²) |

| • الحضر | 979٫91 كم² (378٫35 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 560 m (1٬840 ft) |

| التعداد (2021) | |

| • بلدة | 37٬799 |

| • الكثافة | 1٬300/km2 (3٬400/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 60٬681 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| الرمز البريدي | 2500 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 078 |

| لوحة السيارة | KH |

کيوستنديل ( Kyustendil ؛ بالبلغارية: Кюстендил [kʲustenˈdiɫ]) is a town in the far west of Bulgaria, the capital of the Kyustendil Province, a former bishopric and present Latin Catholic titular see.

The town is situated in the southern part of the Kyustendil Valley, near the borders of Serbia and North Macedonia; 90 km southwest of Sofia, 130 km northeast of Skopje and 243 km north of Thessaloniki. The population is 37 799, with a Bulgarian majority and a Roma minority. During the Iron Age, a Thracian settlement was located within the town, later known as Roman in the 1st century AD. In the Middle Ages, the town switched hands between the Byzantine Empire, Bulgaria and Serbia, prior to Ottoman annexation in 1395. After centuries of Ottoman rule, the town became part of an independent Bulgarian state in 1878.

الأسماء

The modern name is derived from Kösten, the Turkified name of the 14th-century Serbian magnate Constantine Dragaš, from Latin constans, "steadfast" + the Turkish il "shire, county" or "bath/spa".[1][2] The town was known as Pautalia (باليونانية: Παυταλία) in Antiquity and as Velbazhd (Latin Velebusdus, Medieval Greek: Belebousda) in the Middle Ages.

أصل الاسم

Kyustendil Ridge in Graham Land, Antarctica is named after the city,[3] and Pautalia Glacier on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after Pautalia (its Thracian ancestor settlement).[4]

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ والعصر الروماني

A Thracian settlement was founded at the place of the modern town in the 5th-4th centuries BC and was known for its asclepion, a shrine dedicated to medicine god Asclepius.

Under the name Pautalia (باليونانية قديمة: Παυταλία or Πανταλία) it was a town in the district of Dentheletica. Its position in the Peutinger Table places Pautalia at Kyustendil; and the situation of this town at the sources of the Strymon agrees remarkably with the figure of a river-god, accompanied by the "legend" Στρύμων ("Strymon"), on some of the autonomous coins of Pautalia, as well as with the letters ΕΝ. ΠΑΙΩ. ("En. Paio"), which, on other coins, show that the inhabitants considered themselves to be Paeonians, like the other inhabitants of the banks of that river. On another coin of Pautalia, the productions of its territory are alluded to, namely, gold, silver, wine, and corn.[5] In the reign of Hadrian, the people both of Pautalia and Serdica added Ulpia to the name of their town, probably in consequence of some benefit received from that emperor. Stephanus of Byzantium has a district called Paetalia (Παιταλία), which he assigns to Thrace, probably a false reading.[6]

In the 1st century AD, it was administratively part of Macedonia. Later the city was part of the province of Dacia Mediterranea and the third largest city in the province.

The Roman fortress of Pautalia of the 2nd to 4th century had an area of over 29 hectares (appr. 72 acres). The fortress wall was built mainly of granite blocks and unusually its façade was supported with pillars and arches behind. The wall was 2.5m wide allowing small catapults to be mounted atop.

A second, smaller fortress of area 2 hectares was built in the town in the 4th century (known by its later Ottoman name Hisarlaka).

Many Thracian and Roman objects are exhibited in the town's Regional History Museum, most notably an impressive numismatic collection.

Recent excavations have revealed an early Christian, late Roman monumental bishop's palace.[7]

العصور الوسطى

The town was mentioned under the Slavic name of Velbazhd (Велбъжд, meaning "camel")[8] in a 1019 charter by the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. It became a major religious and administrative centre of the Byzantine Empire, and subsequently the Second Bulgarian Empire after Kaloyan conquered the area between 1201 and 1203.

In 1282, Serbian king Stefan Milutin defeated the Byzantine Empire and conquered Velbazhd.

In 1330, the Serbs defeated the Bulgarians in the vicinity, effectively keeping the region to the Serbian Kingdom. Serbian magnate Dejan, one of the prominent figures of the Serbian Empire and its subsequent fall, had initially held a large province in the Kumanovo region under Dušan, and was later as despot under Uroš V assigned the Upper Struma river with Velbuzhd.[9][10] Upon Dejan's death, his possessions in Žegligovo and Upper Struma were given to his two sons, Jovan Dragaš (d. 1378) and Konstantin (d. 1395). The Dejanović brothers ruled a spacious province in eastern Macedonia,[11] in the southern lands of the Empire, and remained loyal to Uroš V,[12] until 1373, when Orhan Gazi's Ottoman army compelled Jovan to recognize Ottoman vassalage.[13]

العصر العثماني

كانت المدينة مركز سنجق في رومليا المحافظة العامة، بعد أن كان المركز في ولايات بيتولا و نيش. وكانت مركز قضاء في سنجق صوفيا في ولاية طونه حتى إنشاء إمارة بلغاريا في 1878.

الحديث

The residents of Kyustendil took an active part in the Bulgarian National Revival and crafts and trade flourished. The town was liberated from Ottoman rule on 29 January 1878.

السكان

According to the 2021 census, the population of Kyustendil is 37,799 people.[14]

التركيبة اللغوية العرقية والدينية

According to the 2011 census data, people who chose to declare their ethnic identity were distributed as follows:[15][16]

- البلغار: 36,732 (82.5%)

- الغجر: 5,179 (11.6%)

- الأتراك: 2 (0.0%)

- غيرهم: 143 (0.3%)

- Indefinable: 296 (0.7%)

- Undeclared: 2,161 (4.9%)

الإجمالي: 44,513

Roma people are mainly concentrated within the town limits. In the meantime, about a fourth of Bulgarians live in the surrounding villages, also part of the Municipality of Kyustendil.

الدين

Kyustendil today belongs to the Sofia diocese in regards of Orthodox church-administrative structure. The city is the center of the vicarage and the Kyustendil Eparchy; in the past, Kyustendil was the seat of the diocese, that latter was closed in 1884. The majority of the urban population profess the Orthodox faith today.

There are several Christian denominations associated with Protestantism and a small Jewish community. During Ottoman rule Kyustendil had a population mostly professing Islam, but of the many mosques of the time, now only two remain. Today the city has only Christian churches operating.

In Antiquity, Pautalia was a bishopric in the Roman province of Dacia Mediterranea, suffragan to the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Sardica, in the sway of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Its only recorded residential bishop was

- Evangelius, who was summoned to Constantinople by Byzantine emperor Anastasius I Dicorus in 516 during the controversy against Monophysitism.

During the brief Late Medieval period, when the Bulgarian Church entered in full communion with Rome (instead of Orthodox Constantinople), one of its three 'Uniate Catholic' (equivalent to modern Eastern Catholic) sees was Velebusdus, which was even raised to a Metropolitan Latin Archbishopric as Pope Innocent III sent its incumbent Athanasius the archiepiscopal pallium on 25 February 1204.

مقر الكرسي البابوي اللاتيني

The archdiocese was nominally restored in 1933 as Latin Metropolitan Titular archbishopric of Velebusdus (Latin) / Velebusdo (Curiate Italian) / Velesdien(sis) (Latin adjective).

It has had the following incumbents, so far of the fitting Metropolitan (highest; perhaps some merely of intermediary Archiepiscopal) rank :

- Ferdinand Stanislaus Pawlikowski (1953.12.07 – death 1956.07.31) as emeritate and promotion; formerly Titular Bishop of Dadima (1927.02.25 – 1927.04.26) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Seckau (Austria) (1927.02.25 – 1927.04.26), succeeded as Bishop of Seckau (1927.04.26 – 1953.12.07)

- Aston Sebastian Joseph Chichester, Jesuit Order (S.J.) (1956.11.23 – death 1962.10.24) as emeritate, formerly Titular Bishop of Ubaza (1931.03.04 – 1955.01.01) as only Apostolic Vicar of Salisbury (then in (Southern) Rhodesia, now in Zimbabwe) (1931.03.04 – 1955.01.01) promoted as first Metropolitan Archbishop of Salisbury (now Harare, Zimbabwe) (1955.01.01 – 1956.11.23)

- Antônio de Almeida Lustosa, Salesians (S.D.B.) (1963.02.16 – resigned 1971.03.16) as emeritate, formerly Bishop of Uberaba (Brazil) (1924.07.04 – 1928.12.17), Bishop of Corumbá (Brazil) (1928.12.17 – 1931.07.10), Metropolitan Archbishop of Belém do Pará (Brazil) (1931.07.10 – 1941.07.19), Metropolitan Archbishop of Fortaleza (Brazil) (1941.07.19 – 1963.02.16); died 1976

- Eugène Klein, Sacred Heart Missionaries (M.S.C.) (1971.06.05 – 1972.04.07) as Coadjutor Archbishop of Nouméa (New Caledonia) (1971.06.05 – 1972.04.07), succeeding as Metropolitan Archbishop of Nouméa (1972.04.07 – 1981); previously Titular Bishop of Echinus (1960.06.14 – 1966.11.15) as Apostolic Vicar of Yule Island (Papua New Guinea) (1960.06.14 – 1966.11.15), then Bishop of Bereina (Papua New Guinea) (1966.11.15 – retired 1971.06.05), died 1992

- Peter Yariyok Jatau (1972.06.26 – 1975.04.10) as Coadjutor Archbishop of Kaduna (Nigeria) (1972.06.26 – 1975.04.10), next succeeded as Metropolitan Archbishop of Kaduna (1975.04.10 – retired 2007.11.16)

- Enzio d'Antonio (1979.06.24 – 1982.05.13) as intermezzo : previously Archbishop-Bishop of Trivento (Italy) (1975.03.18 – 1977), Coadjutor Archbishop of Boiano–Campobasso (Italy) (1975.03.18 – 1977.01.31) succeeding as Metropolitan Archbishop of Boiano-Campobasso (1977.01.31 – 1979.06.24); later last Archbishop of Lanciano (Italy) (1982.05.13 – 1986.09.30), restyled first Archbishop of Lanciano–Ortona (Italy) (1986.09.30 – retired 2000.11.25)

- José Manuel Estepa Llaurens (1983.07.30 – 1989.11.18) first as Archbishop Military Vicar of Spain (Spain) (1983.07.30 – 1986.07.21), restyled Archbishop Military Ordinary of Spain (1986.07.21 – retired 2003.10.30); later Titular Archbishop of Italica (1989.11.18 – 1998.03.07), created Cardinal-Priest of San Gabriele Arcangelo all'Acqua Traversa (2010.11.20 [2011.04.29] – ...); previously Titular Bishop of Tisili (1972.09.05 – 1983.07.30) as Auxiliary Bishop of Madrid (Spain) (1972.09.05 – 1983.07.30)

- Archbishop Gábor Pintér (2016.05.13 – ...), papal diplomat : Apostolic Nuncio to Belarus, no previous prelature.

الاقتصاد

The city is the center of light and manufacturing industry: logging, footwear, knitwear, ready-made clothes, toys, packaging, alcohol producers, bakery, printing and canning industries. There are companies for the production of condensers, power transformers, household and kitchen furniture and joinery. Hotels and tourism have evolved in recent years. The region has traditions in fruit growing and trade in fresh and dried fruits.

Kyustendil is a center of an agricultural area with centuries-old traditions in the field of fruit growing, which is why the town and its surroundings are known as the "Orchard Garden of Bulgaria".[بحاجة لمصدر]

الجغرافيا

Kyustendil is a national balneological resort at an altitude of 600 metres. There are more than 40 mineral springs in the town. The waters have a high content of sulfite compounds. These are used for the treatment of the locomotory system, gynecological and other kinds of diseases. The resort region includes several baths, balneological complexes and others.

Kyustendil is located at the foot of the Osogovo mountain, on both banks of the Banshtica River and is a well-known centre of balneology and fruit growing. The town is 90 kilometres southwest of Sofia, 69 km northwest of Blagoevgrad and 22 km from the border with North Macedonia and Serbia. The fortress was built by the Romans. Thermae, basilicas, floor mosaics have been uncovered.[8]

المناخ

Kyustendil has a mediterranean climate with continental influence (because of the Struma river). The average annual temperature is around 13 °C (55 °F). The highest average temperatures are in July and August at 22 to 23 °C (72–73 °F) and lowest in January at 1 to 2 °C (34–36 °F). The annual temperature range is 23 °C (41 °F).Summers are hot and long, winters are short and cool, spring comes early and stays steady after the first days of March and the autumn is long, warm and sunny while maintaining stable until the end of November. Rainfall is moderate – average 604 mm (23.8 in), and there is snow on average 10–12 days in winter, although it may vary significantly. Due to moderately severe cloudy and hazy low (average 20 days per year) duration of sunshine is significant – about 2,300 hours per year. The second half of the summer and early autumn in the town are the sunniest of the year, and the cloud cover is mostly in the winter months. Humidity is moderate. It varies between 65 and 70%, and is relatively low in the summer months (especially in August). Kyustendil valley is characterized by low windiness, spring being the most windy season and autumn the most quiet. The average annual wind speed is 1.4 m/s (4.6 ft/s). During the winter and spring months in the city appears warm and gusty wind "foehn", which causes sudden warming of time. The temperature regime is characterized by some special features. Winter temperature inversions occur, and in the summer as a result of overheating of the daily maximum air temperatures rise to 35 to 38 °C (95–100 °F). Summer nights are mild or warm with temperatures in the range of 18 to 23 °C (64–73 °F), although temperatures tend to drop below 19 °C (66 °F) in the early mornings for about two hours. The lowest temperature in the city is measured on 20 January 1967 at −22.4 °C (−8.3 °F), and the highest 43.2 °C (110 °F) reached both in July and August, most recently on 24 July 2007.

| بيانات المناخ لـ کيوستنديل، بلغاريا (2010–2022) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 6.2 (43.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 1.5 (34.7) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 48 (1.9) |

45 (1.8) |

42 (1.7) |

52 (2.0) |

68 (2.7) |

65 (2.6) |

54 (2.1) |

36 (1.4) |

38 (1.5) |

59 (2.3) |

62 (2.4) |

55 (2.2) |

624 (24.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 92 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 85 | 117 | 168 | 214 | 261 | 314 | 323 | 312 | 223 | 151 | 106 | 75 | 2٬349 |

| Source: Stringmeteo.com[17] | |||||||||||||

| كيوستنديل | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جدول طقس (التفسير) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

أشخاص بارزون

- Constantine Dragaš, 14th-century local Serbian ruler

- Ilyo Voyvoda (1805–1898), hajduk, revolutionary and Bulgarian liberation fighter (died in Kyustendil)

- Vladimir Dimitrov (1882–1960), painter

- Dimitar Peshev (1894–1973), World War II Minister of Justice and Deputy speaker of the Parliament who prevented the deportation of the Bulgarian Jews to Nazi death camps

- Todor Angelov (1900–1943), communist revolutionary and Belgian resistance fighter

- Nikolay Diulgheroff (1901–1982), futurist artist

- Marin Goleminov (1908–2000), composer

- Irina Taseva (1910–1990), Bulgarian actress

معرض

The municipality hall (architect Friedrich Grünanger)

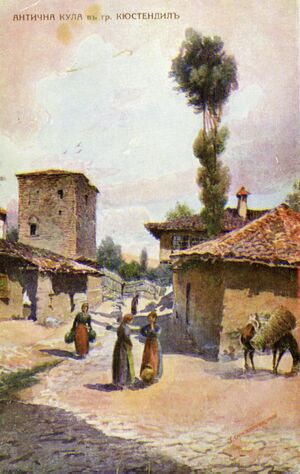

10th-11th-century Church of St George in the Kolusha neighbourhood

Timber-framed tower

انظر أيضاً

- FC Velbazhd Kyustendil (Pautalia during World War II)

- List of Catholic dioceses in Bulgaria

المراجع

- ^ Ćorović 2001, ch. 3, XIII. Boj na Kosovu

- ^ Матанов, Христо (1986). "Феодални княжества и владетели през последните десетилетия на XIV век". Югозападните български земи през XIV век (in البلغارية). София: Наука и изкуство. p. 126.

- ^ Kyustendil Ridge. SCAR Composite Antarctic Gazetteer.

- ^ Pautalia Glacier. SCAR Composite Antarctic Gazetteer.

- ^ Joseph Hilarius Eckhel, Doctrina numorum veterum, vol. ii. p. 38

- ^

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Pautalia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Pautalia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

- ^ "Archaeologists Discover Residence of Early Christian Bishop of Ancient Roman City Pautalia in Bulgaria's Kyustendil". 28 April 2018. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ أ ب Adrian Room, "Placenames of the World" ISBN 0-7864-2248-3 McFarland & Company (2005)

- ^ Mihaljčić 1989, pp. 79-81

- ^ Fajfric, 42

- ^ Samardzic 1892 p. 22:

Синови деспота Дејана заједнички су управљали пространом облашћу у источној Македонији, мада је исправе чешће потписивао старији, Јован Драгаш. Као и његов отац, Јован Драгаш је носио знаке деспотског достојанства. Иако се као деспот помиње први пут 1373, сасвим је извесно да је Јован Драгаш ову титулу добио од цара Уроша. Високо достојанство убрајало се, како је …

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 358

- ^ Edition de l'Académie bulgare des sciences, 1986, "Balkan studies, Vol. 22", p. 38

- ^ https://nsi.bg/bg/content/2981/%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5-%D0%B8-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BB

- ^ (in بلغارية) Population on 1 February 2011 by provinces, municipalities, settlements and age; National Statistical Institute Archived 8 سبتمبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Population by province, municipality, settlement and ethnic identification, by 1 February 2011; Bulgarian National Statistical Institute Archived 21 مايو 2013 at the Wayback Machine (in بلغارية)

- ^ Stringmeteo.com Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Фактически данни » начало".

المصادر والوصلات الخارجية

Media related to کيوستنديل at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to کيوستنديل at Wikimedia Commons- Kyustendil District Administration Provides information about the region, photos, historical review, and development projects Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Kyustendil tourist destination – tourism opportunities in the Kyustendil region

- Kustendil Info, Information web Portal of Kyustendil

- KnCity.info, a website about Kyustendil

- Kyustendil at Journey.bg

- Kyustendil at BGGlobe

- Regional History Museum

- GCatholic - former (Pautalia) & titular see of Velebusdus

- Bibliography - ecclesiastical history

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, pp. 417 e 432

- Daniele Farlati-Jacopo Coleti, Illyricum Sacrum, vol. VIII, Venece 1817, p. 77 e p. 246

- Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1, p. 130

- Jacques Zeiller, Les origines chrétiennes dans les provinces danubiennes de l'empire romain, Paris 1918, p. 160

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Pautalia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Pautalia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 البلغارية-language sources (bg)

- Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from the DGRG without Wikisource reference

- Articles with بلغارية-language sources (bg)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing بلغارية-language text

- Pages with plain IPA

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the DGRG

- کيوستنديل

- Spa towns in Bulgaria

- Populated places in Kyustendil Province

- Dacia Mediterranea