پنوبسكوت

Seal of the Penobscot Indian Nation | |

| إجمالي التعداد | |

|---|---|

| 2,278 enrolled members[1] | |

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |

| Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec), United States (Maine) | |

| اللغات | |

| English, Canadian French, Eastern Abenaki[2] | |

| الجماعات العرقية ذات الصلة | |

| other Algonquian peoples |

پنوبسكوت ( Penobscot ؛ Panawahpskek) هي قبيلة هندية في أمريكا الشمالية من عرق ألگونكوين ، وكانت منطقتهم حول نهر پنوبسكوت في مين، وكانوا قد حاربوا بجانب الفرنسيين في الحروب الاستعمارية ولكنهم عقدوا سلاما مع الإنكليز عام 1749، ولكن حاربوا ضدهم في حرب الاستقلال الأمريكية، وبعدها تم إسكانهم في جزيرة قرب أولدتاون في نهر پنوبسكوت.

التاريخ

قبل الاتصال بالأوروپيين

Little is known about the Penobscot before their contact with European colonizers. Indigenous peoples are thought to have inhabited Maine and surrounding areas for at least 11,000 years.[3] They had a hunting-gathering society, with the men hunting beaver, otters, moose, bears, caribou, fish, seafood (clams, mussels, fish), birds, and possibly marine mammals such as seals. The women gathered and processed bird eggs, berries, nuts, and roots, all of which were found locally.[4]

The people practiced some agriculture but not to the same extent as that of indigenous peoples in southern New England, where the climate was more temperate.[5] Food was potentially scarce only toward the end of the winter, in February and March. For the rest of the year, the Penobscot and other Wabanaki likely had little difficulty surviving because the land and ocean waters offered much bounty, and the number of people was sustainable.[4] The bands moved seasonally, following the patterns of game and fish.

الاتصال والاستعمار

During the 16th century the Penobscot had contact with Europeans through the fur trade. It was lucrative and the Penobscot were willing to trade pelts for European goods such as metal axes, guns, and copper or iron cookware. Hunting for fur pelts reduced the game, however, and the European trade introduced alcohol to Penobscot communities for the first time. It has been argued that the people are genetically vulnerable to alcoholism, a racist sentiment with no evidence which Europeans frequently tried to exploit in dealings and trade. Penobscot people and other nations made pine beer, which had vitamin C; in addition to being an alcoholic beverage, it had the benefit of allaying the onset of scurvy.

When Europeans arrived, they brought alcohol in quantity. Europeans may have slowly developed enzymes, metabolic processes, and social mechanisms for dealing with a normalized high intake of alcohol, but Penobscot people, though familiar with alcohol, had never had access to the gross quantity of alcohol that Europeans offered.

The Europeans carried endemic infectious diseases of Eurasia that were new to the Native Americans, and the Penobscot had no acquired immunity. Their fatality rates from the introduction of measles, smallpox and other infectious diseases was high. The population also declined due to further encroachment by settlers who cut off access to the Penobscot's main food source of running fish through the process of damming the Penobscot River, the loss of big game through the process of clear cutting of forests for the logging industry and through massacres carried out by settlers. This catastrophic population depletion may have contributed to Christian conversion (among other factors); the people could see that the European priests did not suffer from the pandemics. The latter said that the Penobscot had died because they did not believe in Jesus Christ.[4]

At the beginning of the 17th century, Europeans began to live year-round in Wabanaki territory.[4] At this time, there were probably about 10,000 Penobscot (a number which fell to below 500 by the early 19th century).[6] As contact became more permanent, after about 1675, conflicts arose through differences in cultures, conceptions of property, and competition for resources. Along the Atlantic Coast in present-day Canada, most settlers were French; in New England they were generally English speaking.

The Penobscot sided with the French during the French and Indian War in the mid-18th century (the North American front of the Seven Years' War) after the English refusal to respect the Penobscots' intended neutrality. With the Spencer Phips proclamation of 1755,[7] the British colonies put a bounty on the scalps of all Penobscot. With a smaller population and greater acceptance of intermarriage, the French posed a lesser threat to the Penobscots' land and way of life.[4]

After the English defeated French colonists in the Battle of Quebec in 1759, the Penobscot were left in a weakened position. During the American Revolution, the Penobscot sided with the Patriots and played an important role in defending against British offensives from Canada. But, the new American government did not seem to recognize their contributions. Anglo-American settlers continued to encroach on Penobscot lands.[4]

In the following centuries, the Penobscot attempted to make treaties in order to hold on to some form of land, but, because they had no power of enforcement in Massachusetts or Maine, Americans kept encroaching on their lands. From about 1800 onward, the Penobscot lived on reservations, specifically, Indian Island, which is an island in the Penobscot River near Old Town, Maine. The Maine state government appointed a Tribal Agent to oversee the tribe. The government believed that they were helping the Penobscot, as stated in 1824 by the highest court in Maine that "...imbecility on their parts, and the dictates of humanity on ours, have necessarily prescribed to them their subjection to our paternal control."[4] This sentiment of "imbecility" set up a power dynamic in which the government treated the Penobscot as wards of the state and decided how their affairs would be managed. The government treated as charitable payments those Penobscot funds derived from land treaties and trusts, which the state had control over and used as it saw fit.[4]

المطالبة بالأراضي

In 1790, the young United States government enacted the Nonintercourse Act, which stated that the transfer of reservation lands to non-tribal members had to be approved by the United States Congress. Between the years of 1794 and 1833, the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy tribes ceded the majority of their lands to Massachusetts (then to Maine after it became a state in 1820) through treaties that were never ratified by the US Senate and that were illegal under the constitution, as only the federal government had the power to make such treaties. They were left only the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation.

In the 1970s, at a time of increasing assertions of sovereignty by Native Americans, the Penobscot Nation sued the state of Maine for land claims, calling for some sort of compensation in the form of land, money, and autonomy for the state's violation of the Nonintercourse Act in the 19th century. The disputed land accounted for 60% of all of the land in Maine, and 35,000 people (the vast majority of whom were not tribal members) lived in the disputed territory.

The Penobscot and the state reached a settlement, Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA), in 1980, resulting in an $81.5-million-dollar settlement that the Penobscot could use to acquire more tribal land. The terms of the settlement provided for such acquisition, after which the federal government would hold some of this land in trust for the tribe, as is done for reservation land. The tribe could also purchase other lands in the regular manner. The act established the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission, whose function was to oversee the effectiveness of the Act and to intervene in certain areas such as fishing rights, etc. in order to settle disputes between the state and the Penobscot or Passamaquoddy.[8]

Because it is a federally recognized sovereign nation with direct relations with the federal government, the Penobscot have disagreed with state assertions that it has the power to regulate hunting and fishing by tribal members. The Nation filed suit against the state in August 2012, contending in Penobscot Nation v. State of Maine, that the 1980 MICSA settlement gave the Nation jurisdiction and regulatory authority over hunting and fishing in the “Main Stem” of the Penobscot River as well as on its reservation.[9]

At the request of the Nation, the US Department of Justice has joined the suit on behalf of the tribe. In addition, in an unprecedented step, five Native American congressional representatives from other jurisdictions filed an amici curiae brief in support of the Penobscot in this case. In addition to its reservation, the Nation owns islands in the river extending 60 mi (97 km) upriver; it also acquired hundreds of thousands of acres of land elsewhere in the state, as a result of the 1980 settlement of its land claim. Some analysts predict that this case will be as significant to Indian law and sovereignty as the fishing rights cases of Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s, which resulted in the 1974 Boldt decision affirming their rights to fishing and hunting in their former territories.[9] The five members of the Congressional Native American Caucus who filed are Betty McCollum (D-MN), co-chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus with Tom Cole (R-OK) (Chickasaw); Raúl Grijalva, (D-AZ), vice chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus; Ron Kind (D-WI), vice chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus; and Ben Ray Luján (D-NM), vice chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus.

خرائط

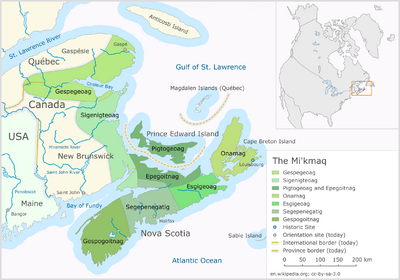

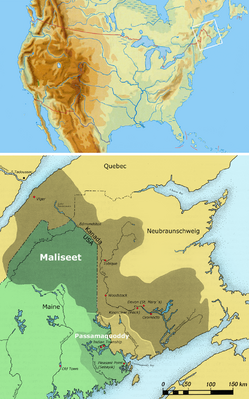

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

See also

- Maine penny

- Penobscot Building

- St. Anne's Church and Mission Site

- Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton

References

- ^ "Penobscot Indian Nation". US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Abnaki, Eastern". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes. American Friends Service Committee, 1989.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes

- ^ James Francis. "Burnt Harvest: Penobscot People and Fire", Maine History 44, 1 (2008) 4-18.

- ^ "History", Penobscot Nation.

- ^ Phips Bounty Proclamation

- ^ Diana Scully. "Maine Indian Claims Settlement: Concepts, Contexts, and Perspectives". 14 February 1995, Abbe Museum. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-15. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ أ ب Gale Courey Toensing, "Congress Members Support 'Penobscot v. Maine' in Unprecedented Court Filing.", Indian Country Today, 5 May 2015, accessed 5 May 2015

External links

- Penobscot Indian Nation, official website

- "The Ancient Penobscot, or Panawanskek". Historical Magazine, February 1872

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Penobscot Indians "|Penobscot Indians]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Penobscot Indians "|Penobscot Indians]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Check|url=value (help)- Penobscot Bingo

- Entirely by hand... from the ground up, Tom Hennessey", Bangor Daily News

- Wabanaki Ethnography, National Park Service

- Harrison, Judy. "Indian Reservation Priests Follow a 300 year old tradition", Bangor Daily News

- Indian Treaties

[[ ]]

- Short description matches Wikidata

- "Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- CS1 errors: URL

- پنوبسكوت

- Algonquian peoples

- Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands

- Native American history of Maine

- Wabanaki Confederacy

- Native American tribes in Maine

- Federally recognized tribes in the United States

- First Nations in Atlantic Canada

- Algonquian ethnonyms

- عرقيات الولايات المتحدة