پاول فون رننكامف

Paul von Rennenkampf | |

|---|---|

Rennenkampf in 1910 | |

| Commander of the Vilna Military District | |

| في المنصب 20 January [ن.ق. 7] 1913 – 19 July [ن.ق. 6] 1914 | |

| العاهل | Nicholas II |

| سبقه | Fyodor Martson |

| خلـَفه | Position abolished |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | 29 April [ن.ق. 17] 1854 Konofer Manor, Konofer, Kreis Hapsal, Governorate of Estonia, Russian Empire (in present-day Konuvere, Rapla County, Estonia) |

| توفي | 1 أبريل 1918 (aged 63) Taganrog, Russian SFSR |

| المثوى | Taganrog Old Cemetery[1][2] |

| القومية | Baltic German |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الولاء | |

| الفرع/الخدمة | |

| سنوات الخدمة | 1870–1915 |

| الرتبة | |

| قاد | 36th Akhtyrka Dragoon Regiment 1st Separate Cavalry Brigade Transbaikal Cossack Army 7th Siberian Army Corps 3rd Siberian Army Corps 3rd Army Corps Vilna Military District (1913–1914) 1st Army |

| المعارك/الحروب | Boxer Rebellion

|

Paul Georg Edler[أ] von Rennenkampf[ب] (روسية: Па́вел Ка́рлович Ренненка́мпф, النطق Pavel Karlovich Rennenkampf; النطق الروسي: [ˈpavʲɪl ˈkarləvʲɪtɕ ˌrʲenʲːɪnˈkampf]; 29 April [ن.ق. 17 April] 1854 – 1 April 1918) was a Baltic German nobleman, statesman and general of the Imperial Russian Army who commanded the 1st Army in the invasion of East Prussia during the initial stage of the Eastern front of World War I. He also served as the last commander of the Vilna Military District.

Rennenkampf gained a reputation as an effective cavalry commander during the Boxer Rebellion and the Russo-Japanese War. Following service in the latter, he led the detachment that suppressed the Chita Republic during the 1905 Russian Revolution. This earned him further promotion, and by the outbreak of World War I Rennenkampf was commander of the Vilna Military District, whose forces were used to form the 1st Army under his command.

He led the 1st Army in the invasion of East Prussia and won an early victory at Gumbinnen in late August 1914, but was relieved of command after defeats at Tannenberg, the Masurian Lakes and Łódź, although he was later proved innocent for the mistakes made in the Battle at Łódź by an official inquiry into his actions. Rennenkampf was shot by the Bolsheviks in Taganrog during the Red Terror in 1918.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Biography

Origin

Paul Georg Edler von Rennenkampff was born on 29 April 1854 in the manor of Konofer (now Konuvere, Märjamaa parish, Estonia) in the then Governorate of Estonia; one of eight children of Captain Karl Gustav Edler von Rennenkampff and Anna Gabriele Ingeborg Freiin von Stackelberg, he came from the Konofer-Tuttomäggi-Sastama branch[4] of the Baltic German Rennenkampff family and was of Lutheran faith. His paternal ancestors were of Westphalian origin, originating in Osnabrück. On his mother's side was the Stackelberg family, whose common ancestor was Carl Adam von Stackelberg, a Swedish cavalry officer and participant in The Great Northern War;[5] he thus remained a fifth cousin of the Russo-Japanese War general Georg von Stackelberg.[6]

Early career

As a youth, Rennenkampf was educated in the Tallinn Knight and Cathedral School (ألمانية: Die Estländische Ritter- und Domschule zu Reval; الإستونية: [Tallinna Toomkool] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), a German-speaking school established especially for local Baltic German aristocrats. Upon graduation, he joined the military as a non-commissioned officer in the 89th Infantry Regiment. He graduated the ru (Helsingfors Junker Infantry School) in Helsinki and began his military career with the Lithuanian 5th Lancers Regiment. He graduated at the top of his class from the Nicholas General Staff Academy in St. Petersburg (or at the first category) in 1881.

From late August to late November 1884, he was an over-officer of the 14th Army Corps, specialising in instruction. In late September 1886, he was the chief of staff of the Warsaw Military District, serving under General and later Field Marshal Count Gurko.

In early 1888, he was appointed to the Kazan Military District. Rennenkampf subsequently became the senior adjutant to the headquarters of the Don Cossacks. In late October 1889, he was appointed headquarters officer for special assignment at the 2nd Army Corps headquarters. In late March 1890, he was appointed the chief of staff of the Osowiec Fortress in Russian Poland. The same year he was promoted to colonel, after which he served in several different regiments until late November 1899, when he was appointed chief of staff of the Transbaikal region, and was promoted to major general.

تمرد الملاكمين

From 1900 to 1901, Rennenkampf participated in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China. He distinguished himself with extreme success during the campaign, receiving both the 4th and 3rd classes of the Order of St. George for military distinction.[7][8]

He acquired a name and wide popularity in military circles during the Chinese campaign (1900), for which he received two St. George crosses. The military, in general, were skeptical of the "heroes" of the Chinese war, and was considered "not real." But the cavalry raid of Rennenkampf, in its daring and courage, deserved universal recognition. It began in late July 1900, after the occupation of Aigun (near Blagoveshchensk). Rennenkampff, with a small detachment of three arms, defeated the Chinese in a strong position along the ridge of the Small Hingan and, having overtaken his infantry, with fourteen hundred Cossacks and a battery, having made 400 kilometers in three weeks with continuous skirmishes, captured a large Manchurian city of Qiqihar with a sudden raid. From here the high command assumed a systematic offensive against Jirin, gathering large forces in the 3 regiments of infantry, 6 regiments of cavalry and 64 guns, under the command of the famous general von Kaulbars ... But, without waiting for the detachment to be collected, General von Rennenkampff, taking with him 10 hundred Cossacks and a battery, on August 24 moved forward along the Sungari valley; On the 29th he captured Boduna, where 1,500 boxers surrendered unawares to him without a fight; September 8, seized Kaun-Zheng-tzu, leaving here five hundred and a battery to ensure its rear, with the remaining 5-hundred, having done 130 km per day, flew to Jilin. This match, unparalleled in its speed and suddenness, caused the Chinese, exaggerating to the extreme the strength of Rennenkampff, the impression that Kirin, the second most populated city and the most important city of Manchuria, surrendered, and the big garrison folded it. A handful of Rennenkampff Cossacks, lost among the mass of the Chinese, for several days, until reinforcements arrived, was in a preoriginal position ... – Anton Denikin[9]

In mid-September, Rennenkampf left for Dagushan, leaving hundreds of troops to protect the mint and arsenal. After several days of resetting, he attacked and occupied Tieling and Mukden with his detachment attacked, maintaining control until October. Within this time, the general survived numerous assassination attempts; during one encounter, when he and his troops entered a manor, three Chinese men with spears charged toward the general, with a Cossack, Fyodor Antipyev, saving the general and being stabbed himself. For military distinction, he was awarded the Order of St. George of the 3rd degree.

The raid of the cavalry detachment of Rennenkampf was one of the most successful and decisive military operations in the Boxer Rebellion. In just three months of actions, Russian troops had taken over 2,500m2 of land, the best trained Chinese troops stationed at Heilongjiang were defeated and pushed out of Manchuria, and rebel detachments were dispersed, leading to the cessation of the Chinese resistance movement against their Russian occupiers.

الحرب الروسية اليابانية

In February 1904, after the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Rennenkampf was appointed commander of the Trans-Baikal Cossack Division.[10] In June, he was promoted to lieutenant-general in recognition of his military distinction.

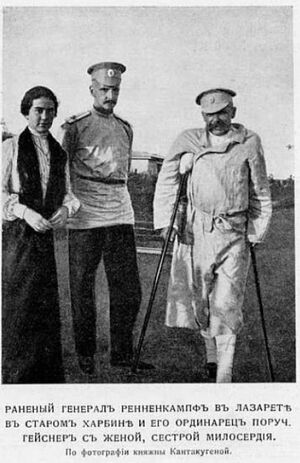

In late June 1904, while scouting the Japanese positions at Liaoyang, he was shot in the leg, shattering the shin. After less than two months he returned to active service, without fully recovering from his wounds. In the Battle of Mukden, Rennenkampf again distinguished himself commanding the Tsinghechensky detachment, which was stationed at the left flank of the 1st Manchurian Army led by General Nikolai Linevich. During the battle, he showed great persistence, which, combined with other reinforcements, was able to repulse Field Marshal Kawamura's offensive.

According to some historians and writers, after the Battle of Mukden, a personal conflict occurred between Rennenkampf and General Samsonov and it came to an exchange of blows, which made the two of them lifelong foes; some other historians argue that there could be no clashes between the generals.[weasel words] The main source of this rumor is the memoirs of the German general Max Hoffmann, who was an observer with the Imperial Japanese Army during the war; capable of personally observing relations among Russian generals, he would subsequently become one of Rennenkampf's enemies in the First World War. In his memoirs, which refer again to rumors, Hoffmann mentioned that both generals quarrelled in Liaoyang after the battle; however, this claimed argument remains physically impossible, as Rennenkampf was seriously injured at this time.

After the war, Rennenkampf commanded numerous army corps, including the 7th Siberian Army Corps, the 3rd Siberian Army Corps and the 3rd Army Corps.

1905 Russian Revolution

After the war, Rennenkampf commanded an infantry battalion with several machine guns which followed a train in Harbin, restoring communications between the Manchurian Army and Western Siberia. Within this time, the Revolution broke out; this task remained interrupted via a revolutionary movement in Eastern Siberia, the Chita Republic. Rennenkampf and his forces were sent to suppress the movement, successfully restoring order in Chita.

After this campaign, he remained a target for assassination by numerous rebel groups and several plots to assassinate him were planned. In late October 1906, he faced an assassination attempt while walking along the street with two of his adjutants; a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, who was sitting on a bench, threw a bomb onto the general's feet. However, rather than destroying Rennenkampf and his adjutants, the explosion merely stunned them. The attempted assassin was later arrested and tried.

The decisive actions of Rennenkampf in the course of a war and in the suppression of rebellion led to further advancements in his career. In late December 1910, he was promoted to General of the Cavalry, then promoted to General-Adjutant in 1912. A further promotion to commander-in-chief of all troops within the Vilna Military District followed in mid-January 1913.

World War I

In the beginning of the First World War, Rennenkampf was appointed commander of the 1st Army of the Northwestern Front, under commander-in-chief General Yakov Zhilinsky; his rival Samsonov was the commander of the 2nd Army invading East Prussia from the south. On 7 August 1914, Rennenkampf and his troops entered East Prussia from the east. While retreating upon orders from the defending 8th Army commander, General Maximilian von Prittwitz, a gap formed between the Russian armies; exploiting this, the Imperial German 1st Division, commanded by General Hermann von François, counterattacked at the Battle of Stallupönen, initiating the Eastern Front of the war. Although it was a victory for the Germans, Russian artillery bombardment halted the German offensive, causing François to withdraw to the town of Gumbinnen.

Rennenkampf continued his advance, defeating the 8th Army under the Prittwitz's command at the Battle of Gumbinnen. But due to a later incorrect assessment made by Zhilinsky, the victory at Gumbinnen did not develop. After the battle, Rennenkampf was ordered by Zhilinsky to launch an offensive against the heart of East Prussia, Königsberg, but his army did not link up with Samsonov's 2nd Army due to a mistake made by Zhilinsky. As a result, the German 8th Army under the new commander, General (later field marshal) Paul von Hindenburg, charged through the gap, then encircled and nearly wiped out the 2nd Army near Allenstein (the Battle of Tannenberg). When the desperate Samsonov sent his appeals for help, instead of immediately replying and heading south to aid Samsonov, Rennenkampf almost completely ignored the appeal. When he finally began to head south, he and his men started too late and proceeded more slowly than they should have,[بحاجة لمصدر] contributing to the defeat of the 2nd Army. After the battle, Samsonov, fearing being held responsible for the defeat, committed suicide.

After the 2nd Army's annihilation at the Battle of Tannenberg, Rennenkampf's army took over all the defenses along the Deyma, Lava and the Masurian Lakeland. On 7 September, the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes began, as the Germans attacked the left flank of the 1st Army with a powerful detachment. Zhilinsky broke his promise to provide Rennenkampf with reinforcements from other formations; as a result, the 1st Army had to retreat hurriedly. The 2nd Army Corps, led by General Vladimir Slyusarenko, resisted desperately, as did Rennenkampf himself, who transferred all the cavalrymen, reserves, and troops from the right to left flank of the 20th Army Corps in order to avoid encirclement by Hindenburg. By 15 September, he skillfully withdrew his men from encirclement and withdrew behind the Neman, saving all the remaining troops he had. After this failure, despite his best efforts to blame Rennenkampf for the defeat, Zhilinsky was dismissed and was replaced by the General Nikolai Ruzsky.

In mid-November at Łódź, due to the indecisiveness and mistakes made by Ruzsky, the 1st Army was unable to prevent the XXV Reserve Corps of General Reinhard von Scheffer-Boyadel from escaping out of the encircling movement, causing the front to retreat. A sharp conflict then broke out between the two men. After the incident, Rennenkampf was relieved from his position. His acts during the battle became the subject of a special commission under General Peter von Baranoff; he was even considered being tried for treason, due to his ethnic background. He was then dismissed in early October 1915 "for domestic reasons with a uniform and pension".

After that, he stayed in Petrograd, living in retirement with his wife Vera until the Bolshevik coup. However, his retirement was extremely unsettling, as he was falsely accused of being a traitor, and all across Russia, on streets and in public places, people insulted him for his actions. Even Baltic Germans accused him, as Vera recalled, as being a "terrible Russophile". All these events plunged Rennenkampf into deep moral suffering.[11]

Army chief of staff General Nikolai Yanushkevich wrote the following about the issue of German Generals in the Russian Army to the Minister of War, General Sukhomlinov:

The mass of complaints, libel, and so on, that the Germans (Rennenkampf, Sivers, Müller, etc.) are traitors and that the Germans are being given a move, as well as the mood of military censorship letters convinced that the appointment of Pavel Plehve, with some of his regime and perseverance to carry out operations even with victims, prompted (Grand Duke Nikolai) to abandon the original idea of Plehve and to dwell on a man with a Russian surname.

In a further investigation, it was revealed that it was Ruzsky's strategic mistakes that had let Scheffer-Boyadel and his troops escape from the encirclement. This, however, did not bring Rennenkampf back to service.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

February Revolution

Rennenkampf was arrested shortly after the February Revolution, as many of the revolutionaries remembered his role in the suppression of the Chita Republic back in 1905. He was then questioned by the Extraordinary Investigative Commission of the Russian Republic, although he was not charged with any crimes.

October Revolution and death

Rennenkampf was arrested again after the October Revolution and, like many other tsarist officials, was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress. He was released shortly afterwards due to deteriorating health. After that, he, along with several other tsarist generals, went south to Taganrog, his wife's birthplace, and lived under the protection of a merchant named Smokovnikov.

After the Red Army took over the city, Rennenkampf disappeared, disguised as a Greek subject named Mandusakis, but was tracked down by the Red Army and identified, after which he was brought to the headquarters of the Bolsheviks under the order of Red Army commander-in-chief Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko. After arriving, the former general was offered a command in the Red Army, with refusal implying death. Rennenkampf refused to defect to the Bolsheviks, saying:

I'm old. I have not much left to live, for the salvation of my life, I will not become a traitor and will not go against my own. Give me a well-armed army, and I will go against the Germans, but you have no army; to lead this army would mean leading people to slaughter, I will not take this responsibility on myself.[12]

At the time, the Germans were advancing toward Taganrog; the Czechs and Anton Denikin's White Army were as well. As a result, Rennenkampf was taken hostage by the Bolsheviks and brought near the railway tracks running from the Martsevo station to the Baltic. Upon arrival, Rennenkampf was forced to dig his own grave, then stabbed before being executed with a bullet to the temple.

الأعقاب

According to Rennenkampf's wife Vera's memoirs, after his death, the Whites were told that Rennenkampf was on the way to Moscow. In May 1918, after the Whites had taken over Taganrog, a stick was found stuck in the ground near the railway tracks running from the Martsevo station to the Baltic Plant. After they dug up the grave, they found several bodies, including one nearly naked with a bullet wound to the head. When they took the corpses to a local cemetery (now the Taganrog Old Cemetery) in the city, Rennenkampf's wife Vera arrived at the cemetery and identified the nearly naked corpse as her husband Paul.

The White troops and Rennenkampf's wife held a funeral that fulfilled Rennenkampf's wish of being buried in an unmarked mass grave with other victims of the Red Terror. But other than her memoirs, there is no evidence of Rennenkampf's burial in the Old Cemetery in Taganrog.

In recent years, researchers at the Hoover Institution archives of the Stanford University found several photos taken during the civil war. In the photos, a marked grave was clearly seen on the left with "P. K. Rennenkampf"[ت] written on it. This allowed historians and researchers to determine and establish the final resting place of Rennenkampf at the burial ground in the Old Cemetery in Taganrog.[13][14][15]

Family

Born into a large and wealthy family, Rennenkampf had five brothers and two sisters.[16][17] His brothers included Woldemar Konstantin von Rennenkampff (1852–1912), a cavalryman and the director of the Russian gun industry, and Georg Olaf von Rennenkampff (1859–1915), a chief of powder manufacturing in Zawiercie.

Rennenkampf married four times. In 1882, he married Adelaide Franziska Thalberg, with whom he had three children: Adelaide Ingeborg (1883–1896), Woldemar Konstantin (1884) and Iraida Hermaine (1885–1950). Thalberg died in 1888 after only six years of marriage.

In 1890, in Vilno, Rennenkampff married Lydia Kopylova, with whom he had one more child, Lydia (1891–1937). He then married Evgenia Dmitryevna Grechova, with whom he had no children.

Finally, in 1907 in Irkutsk he married Vera Nikolayevna Krassan (Leonutova),[ث] with whom he had a daughter, Tatyana (1907–1994), and adopted Vera's daughter Olga (1901–1918) from her first marriage. Unlike his other marriages, Rennenkampf's marriage with Vera was long and happy. Vera, as the wife of the commander of the Vilna Military District, was a trustee and member of a branch of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. When the war broke out, she participated in organizations that cared for the wounded. In Vera's memoirs, she wrote of her founding of the Committee for Assistance to the families of reserve lower ranks, tailoring workshops for the front, and her participation in the formation of the flying car detachment of the Evangelical Red Cross that took the wounded from the battlefield.

After the war and Rennenkampf's death, the fate of his family was unknown, but Vera and Tatyana escaped to Paris, France. Olga was murdered on her doorstep the same month as her stepfather's murder. The rest of the family either fled to Estonia or back to Germany during the civil war.

الذكرى

Before his execution, Rennenkampf had asked his wife Vera to make every effort to "whitewash his name from slander". Vera was not alone in considering her husband to be innocent of the strategic mistakes that led to the Russian defeats in the East Prussian campaign; a significant part of the White émigrés, including generals Baron Wrangel, Anton Denikin, and Nikolai Golovin, shared that view.

To rehabilitate the general's image and to "give the light to the real face of General Paul Georg Edler von Rennenkampff", on the initiative of his wife in November 1936 the historical society of the "Friends of Rennenkampf" ("Les Amis de Rennenkampf") was founded in Paris. The honorary chairman was Vera herself, and the president of the bureau was the husband of Rennenkampf's daughter Tatyana. The honorary committee included the widow of Baron Wrangel – Baroness Olga Mikhailovich, General Nikolai Epanchin, Prince Belosselsky-Belozersky and others.[18]

Personal collection

A collection of Chinese art pieces looted by Rennenkampf during the 1900 Chinese Campaign is on display in the Alferaki Palace in Taganrog.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In popular culture

- In the 2005 Russian film The Fall of the Empire, Rennenkampf was portrayed by Russian actor Sergei Nikonenko.

- Rennenkampf was among 15 Russian generals and admirals to be featured in the postcards produced by the French confectionery company Chocolat Guérin-Boutron, with the description "86. Rennenkampf, général russe".[19]

Honours and awards

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Russian Empire

Order of St. Stanislaus, 3rd class (1884)

Order of St. Stanislaus, 3rd class (1884) Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd class (1894)

Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd class (1894) Order of St. Stanislaus, 1st class with swords (31.3.1905)

Order of St. Stanislaus, 1st class with swords (31.3.1905) Order of St. Anne, 3rd class (1888)

Order of St. Anne, 3rd class (1888) Order of St. Anne, 2nd class (1895)

Order of St. Anne, 2nd class (1895) Order of St. Anne, 1st class (1907)

Order of St. Anne, 1st class (1907) Order of St Vladimir, 4th class (1899)

Order of St Vladimir, 4th class (1899) Order of St Vladimir, 3rd class (1903)

Order of St Vladimir, 3rd class (1903) Order of St Vladimir, 2nd class with swords (1914)

Order of St Vladimir, 2nd class with swords (1914) Order of St. George, 4th class (12.8.1900)

Order of St. George, 4th class (12.8.1900) Order of St. George, 3rd class (22.12.1900)

Order of St. George, 3rd class (22.12.1900) Golden Weapon with diamonds and the inscription "For Bravery" (1906)

Golden Weapon with diamonds and the inscription "For Bravery" (1906)

Foreign

- قالب:Country data Kingdom of Sweden:

Order of the Sword (before 1914)

Order of the Sword (before 1914)

الإمبراطورية النمساوية:

الإمبراطورية النمساوية:

Order of the Iron Crown (before 1914)

Order of the Iron Crown (before 1914)

Publications

- Auf dem Fluß Amur und in der Mandschurei, war reports of Generals Rennenkampf of 1904, Part I, Voyenny Sbornik (military collection), Nr. 3, S. 89–108.

- Auf dem Fluß Amur und in der Mandschurei, war reports of Generals Rennenkampf of 1904, Part II, Voyenny Sbornik, Nr. 4, S. 57–86.

- Auf dem Fluß Amur und in der Mandschurei, war reports of Generals Rennenkampf of 1904, Part III, Voyenny Sbornik, Nr. 5, S. 55–86.

- Der zwanzigtägige Kampf meines Detachements in der Schlacht von Mukden, Berlin: Mittler & Sohn (1909)

Notes

- ^ قالب:German title Edler

- ^ The spelling of his last name varies in different works between Rennenkampff, Rennenkampf, Remenkampe and Remmenkamp.[3]

- ^ P. K. Rennenkampf being the short form of Rennenkampf's Russian name Pavel Karlovich Rennenkampf

- ^ Krassan being the surname from her first marriage with Georg Krassan

References

- ^ "American footprint"..

- ^ "The burial place of General P.K. Rennenkampf"

- ^ Transehe-Roseneck 1930, pp. 776–779.

- ^ Stackelberg 1930, p. 205.

- ^ Carl Adam Freiherr von Stackelberg/ Genealogy on the Internet by Stackelberg

- ^ Carl Adam von Stackelberg: Stackelberg was descended from Karl Wilhelm, while Rennenkampff was descended from Adam Friedrich.

- ^ [1] Recipients of the Order of St. George, 4th degree

- ^ [2] Recipients of the Order of St George, 3rd degree

- ^ Denikin, Anton The path of the Russian officer. – M .: Sovremennik (1991)

- ^ Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Rennenkampf Pavel Karlovich: last paragraph of the passage

- ^ Pavel Karlovich von Rennenkampf

- ^ "Pay the debt of memory"

- ^ "American footprint".

- ^ "The burial place of General P.K. Rennenkampf"

- ^ Welding 1970, p. 621.

- ^ Stackelberg 1930, p. 209.

- ^ "The Historical Society of the Friends of Rennenkampf (Les Amis de Rennenkampf)"

- ^ "General P.K. Rennenkampf on Guerin-Boutron chocolate leaflet"

- ^ Carl Arvid von Klingspor (1882). Baltisches Wappenbuch. Stockholm. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-543-98710-5. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

Sources

- Connaughton, R.M (1988). The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear – A Military History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–5, London, ISBN 0-415-00906-5.

- Jukes, Geoffrey. The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Osprey Essential Histories. (2002). ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- Warner, Denis & Peggy. The Tide at Sunrise, A History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. (1975). ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

- Stackelberg, Otto Magnus v. Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods Part 2, 3: Estonia. Görlitz (1929)

- Transehe Roseneck, Astaf v. Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthoods Part 1, 2: Livonia, Lfg. 9-15. Görlitz (1929)

- Baltic German Biographical Dictionary 1710-1960. (1970), from the Baltic Biographical Dictionary Digital

External links

- biography at Russojapanesewar.com

- Who's Who: Paul von Rennenkampf

- قالب:Cite EB1922

- Rennenkampff, Paul Georg v. Baltic Biographical Dictionary Digital

- Pavel Karlovich Rennenkampf – Biography, imfromation, personal life

- Newspaper clippings about پاول فون رننكامف in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| مناصب عسكرية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Fyodor Martson |

Commander of the Vilna Military District 20 January [ن.ق. 7] 1913 – 19 July [ن.ق. 6] 1914 |

تبعه Position abolished |

| سبقه Field Marshal Fabian Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken (as the commander-in-chief of the army) |

Commander of the 1st Army 1 August [ن.ق. 18 July] 1914 – 30 November [ن.ق. 17] 1914 |

تبعه Alexander Litvinov |

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from November 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2024

- 1854 births

- 1918 deaths

- People from Märjamaa Parish

- People from Kreis Wiek

- Baltic-German people from the Russian Empire

- Imperial Russian Army generals

- Russian military personnel of the Boxer Rebellion

- Russian military personnel of the Russo-Japanese War

- Russian military personnel killed in World War I

- Recipients of the Order of Saint Stanislaus (Russian), 1st class

- Recipients of the Order of St. George of the Third Degree

- Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 2nd class

- Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd class

- Recipients of the Gold Sword for Bravery

- Victims of Red Terror in Soviet Russia

- Executed military leaders

- Deaths by firearm in Russia