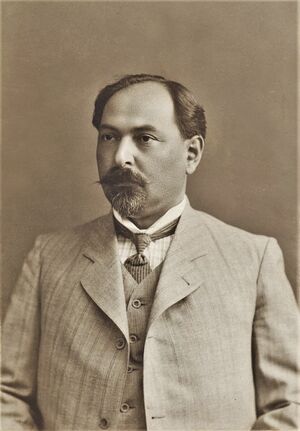

نريمان نريمانوڤ

نريمان نريمانوڤ Nəriman Kərbəlayi Nəcəf oğlu Nərimanov | |

|---|---|

| |

| وزير الشئون الخارجية لأذربيجان ج.ا.س. | |

| في المنصب مايو 1920 – 2 May 1921[1] | |

| الرئيس | گريگوري كامينسكي (الأمين الأول للحزب الشيوعي الأذربيجاني) |

| سبقه | فتحعلي خان خويسكي (ADR) |

| خلـَفه | ميرزا داوود حسينوڤ |

| رئيس مجلس قوميسارات الشعب | |

| في المنصب مايو 1921 – أبريل 1922 | |

| سبقه | منصب مستحدث |

| خلـَفه | غضنفر مسابقوڤ |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | 14 أبريل [ن.ق. 2 أبريل] 1870 تفليس، الامبراطورية الروسية |

| توفي | 19 مارس 1925 (aged 54) موسكو، روسيا ج.ا.ا.س. |

نريمان كربلائي نجفأوغلو نريمانوڤ (آذربيجاني: Nəriman Kərbəlayi Nəcəf oğlu Nərimanov؛ روسية: Нарима́н Кербелаи Наджа́ф оглу Нарима́нов؛ 14 April [ن.ق. 2 أبريل] 1870 – 19 مارس 1925) كان ثورياً من البلشڤيك وكاتب وإعلامي وسياسي ورجل دولة أذربيجاني. ولأكثر قليلاً من عام، بدءاً من مايو 1920، ترأس نريمانوڤ حكومة أذربيجان السوڤيتية. واِنتـُخـِب لاحقاً رئيسا لمجلس الاتحاد لجمهورية عبر القوقاز ا.ا.س.. وكان زعيم الحزب للجنة التنفيذية المركزية للاتحاد السوڤيتي من 30 ديسمبر 1922 حتى يوم وفاته.

في مجال الأدب، ترجم نريمانوڤ إلى التوركية رواية نيقولاي گوگول المفتش العام وكتب العديد من المسرحيات والقصص والروايات، مثل بهادر و سونا (1896). كما كان مؤلف الثلاثية التارخية، نادر شاه (1899).

أحد الأحياء المركزية في باكو وواحدة من أزحم محطات المترو في باكو، ومعهم عدد من الشوارع والمنتزهات والقاعات في أرجاء أذربيجان، وكذلك جامعة طب أذربيجان مسماة على اسمه. وفي محافظة لنكران، توجد بلدة اسمها نريمان آباد تكريماً له. كما توجد بلدات مسماة على اسمه في دول ما بعد الاتحاد السوڤيتي، أساساً في روسيا.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

السيرة

النشأة

وُلِد نريمان نريمانوڤ في 14 أبريل (2 أبريل ن.ق.) 1870 في تفليس، جورجيا، التي كانت آنذاك جزءاً من الامبراطورية الروسية into an ethnic Azerbaijani family. The Narimanov family were middle-class merchants and were able to send their son to the Gori Teachers Seminary, from which he graduated.[2] He went on to attend medical school at "Imperial Novorossiya University" (present-day "Odessa University"), graduating in 1908.[2]

As a young man, Narimanov gained notice as a writer in Azerbaijan even before the revolution of 1905-1907, publishing novels which advocated the abandonment of tired customs and religious superstitions.[2] He simultaneously taught school in the village of Gizel-Adjal, Tiflis Province, where he became closely acquainted with the hard life of the local peasantry. Narimanov was one of the first activists of young Turkic literature. He translated into Turkic Gogol's Inspector and wrote many plays, stories and novels; the most well known among them being the novel, Bahadur and Sona (1896), and a historical trilogy, Nadir-shah (1899).

During the 1905 Revolution, Narimanov joined the Bolshevik party, took an active part and led the student movement in Odessa. He subsequently became one of the organizers of the Social Democratic Party. For these activities, Narimanov was arrested in 1909 وحـُكِم عليه بالنفي الداخلي لخمس سنوات في أستراخان.[2]

السيرة السياسية

After the October Revolution of 1917, Nariman Narimanov became the chairman of the Azerbaijani social democratic political party, Hummet (Endeavor), the forerunner of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan.[2] He did not run for election on the Hummet slate, however, and was thus not a member of the Baku Soviet during the brief reign of the Baku Commune of 1918.[2] He was appointed People's Commissar of National Economy by the Baku Soviet, however.[2]

Following the fall of the Baku Soviet, Narimanov managed to escape the city to Astrakhan, thereby avoiding the grim fate of the 26 Baku Commissars.[2] He was there appointed chief of the Near East Division of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs of Soviet Russia, later moving to a position as Deputy People's Commissar in the Commissariat of National Affairs.[2] Narimanov was an advocate of national autonomy within a federated Soviet structure and is widely viewed as being instrumental in the July 1919 decision of the Politburo to recognize Azerbaijan as an independent Soviet Republic.[2]

In 1920, Narimanov was appointed the chairman of the Azerbaijani Revolutionary Committee (Azrevkom) and, shortly thereafter, the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars' (Sovnarkom) of the Azerbaijani Soviet Republic. In April and May 1922, he took part in the Genoese Conference as a member of the Soviet delegation. In 1922, he was elected the chairman of the Union Council of the Transcaucasian Federation. On 30 December 1922, the first session of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR elected Narimanov as one of the four chairpersons of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR.[2]

In April 1923, Narimanov was elected as a candidate for the Central Committee of the RKP(b) (Russian Communist Party of Bolsheviks). The charismatic moderate nationalist clashed with Joseph Stalin's close associate Sergo Ordzhonikidze, who led the Communist Party in Transcaucasia. As a result of this conflict, Ordzhonikidze had Narimanov transferred to posts in Moscow to remove him from the Caucasus.

الوفاة والذكرى

Narimanov died in bed of a heart attack on 19 March 1925.[2] He was 54 years old at the time of his death. His remains were cremated and his ashes buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.

Leon Trotsky called his death the second biggest loss for the Eastern world after that of Lenin.[3] Sergo Ordzhonikidze described Narimanov as "the greatest representative of our party in the East".[4]

During the Ezhovshchina of the late 1930s, Narimanov was posthumously denounced along with all other members of Hummet for their alleged nationalism.[2] This action was reversed after the liberalization which followed the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and Narimanov was again celebrated as a leading figure in the history of Azerbaijani communism, though in 1959, official CCCPSU policy was still to downplay Narimanov's role and stress that of Shaumian within the Azerbaijani context. It was only in 1972 that Narimanov was fully rehabilitated within his homeland.[2][5]

Narimanov was survived by his wife Gulsum and by his son Najaf, who joined the Red Army in 1938 and graduated from the Kiev Higher Military Radio-Technical Engineering School in 1940. He became a member of the Communist Party in 1942. During the Great Patriotic War, he was the commander of a tank division and took part in the Battle of Stalingrad and the Battle of the Dnieper before being killed in action near Volnovakha in Ukraine.

أذربيجان: Monuments in Baku, Ganja and Sumgayit, cinema, metro station, schools, raion, village streets in Baku also in Imishli (city) and Ganja, Azerbaijan Medical University, central park as well as villages of Narimanly in Shamkir and Geranboy and Narimankend in Bilasuvar, Gobustan, Gədəbəy and Sabirabad regions of Azerbaijan, Nariman Narimanov Stadium.

أذربيجان: Monuments in Baku, Ganja and Sumgayit, cinema, metro station, schools, raion, village streets in Baku also in Imishli (city) and Ganja, Azerbaijan Medical University, central park as well as villages of Narimanly in Shamkir and Geranboy and Narimankend in Bilasuvar, Gobustan, Gədəbəy and Sabirabad regions of Azerbaijan, Nariman Narimanov Stadium. بلاروس: a village in the village hall of Aleksichskom Khoiniki district, Gomel region.

بلاروس: a village in the village hall of Aleksichskom Khoiniki district, Gomel region. جورجيا: a street (changed its name into Kutaisi in 1932),[6] a museum in Tbilisi (not active anymore), culture center, school, monument and street in Marneuli.

جورجيا: a street (changed its name into Kutaisi in 1932),[6] a museum in Tbilisi (not active anymore), culture center, school, monument and street in Marneuli. كازاخستان: Kostanay Airport (Narimanovka).

كازاخستان: Kostanay Airport (Narimanovka). روسيا: Narimanov, Astrakhan Oblast, a khutor in Leninskoye Rural Settlement of Zimovnikovsky District of Rostov Oblast, a settlement in Nurlatsky District of the Republic of Tatarstan, a village in Narimanovsky Rural Okrug of Tyumensky District of Tyumen Oblast, raion in Baskhortostan, avenue and the area in Ulyanovsk, culture center in Shatura, streets in Volgograd, Chernyanka Belgorod regions, Kostroma and Moscow, street near railway of Voronezh. Narimanov's name once given to Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies.

روسيا: Narimanov, Astrakhan Oblast, a khutor in Leninskoye Rural Settlement of Zimovnikovsky District of Rostov Oblast, a settlement in Nurlatsky District of the Republic of Tatarstan, a village in Narimanovsky Rural Okrug of Tyumensky District of Tyumen Oblast, raion in Baskhortostan, avenue and the area in Ulyanovsk, culture center in Shatura, streets in Volgograd, Chernyanka Belgorod regions, Kostroma and Moscow, street near railway of Voronezh. Narimanov's name once given to Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies. ترکمنستان: a street in Bayramali.

ترکمنستان: a street in Bayramali. أوكرانيا: an alleyway in Odessa, a street in Kharkiv, village in Kirovagradskiy Oblast.

أوكرانيا: an alleyway in Odessa, a street in Kharkiv, village in Kirovagradskiy Oblast. أوزبكستان: a city Payarik was once called as "Narimanovka". A city in Taskhent oblast. Senatoruim.

أوزبكستان: a city Payarik was once called as "Narimanovka". A city in Taskhent oblast. Senatoruim.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الهامش

- ^ "Presidential Library. Nariman Narimanov" (PDF). p. 72. Retrieved 2010-07-09.[dead link]

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص George Jackson with Robert Devlin, "Narima Nejefoghi Narimanov" in Dictionary of the Russian Revolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1989; pp. 399-400.

- ^ Leon Trotsky on the memory of Myasnikov, Mogilevskogo, and Artabekova

- ^ The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1939, p. 160.

- ^ Jamil Hasanli, Khrushchev's Thaw and National Identity in Soviet Azerbaijan 1954-1959 p436]

- ^ Qori seminariyasının Azərbaycan şöbəsinin yaradıcısı

للاستزادة

- Audrey Altstadt, The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992.

- The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Third edition. Moscow: 1970-77.

وصلات خارجية

- Nariman Narimanov: Early Years of Bolsheviks - Wrong Direction, Azerbaijan International- AZER.com

- Nariman Narimanov: Son, Let Me Tell You What It Was Really Like - AZER.com

- Nariman Narimanov's museum in Baku

قالب:Political activity in Azerbaijan until 1920

قالب:Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan قالب:Azerbaijani communism

- Articles with dead external links from December 2017

- Articles containing آذربيجاني-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- كتاب اللغة الأذربيجانية

- مواليد 1870

- وفيات 1925

- ثوريون أذربيجانيون

- بولشڤيك

- مدفونون في مقبرة جدار الكرملين

- كتاب من تفليس

- أشخاص من محافظة تفليس

- أذربيجانيون جورجيون

- أعضاء حزب العمل الديمقراطي الاشتراكي الروسي

- سياسيو الحزب الشيوعي الأذربيجاني

- كتاب أذربيجانيون

- ملحدون أذربيجانيون