معاهدة كوريا-اليابان 1876

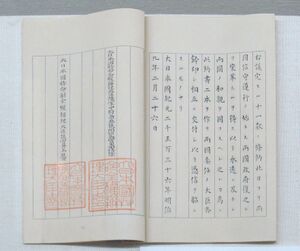

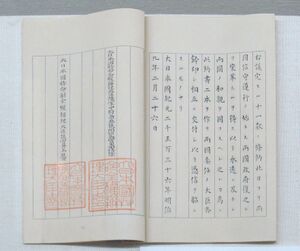

المعاهدة، معروضة | |

| التوقيع | 26 فبراير 1876 |

|---|---|

| تاريخ السريان | 26 فبراير 1876 |

| الموقعون | |

| معاهدة الصداقة الكورية-اليابانية | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| كانجي | 日朝修好条規 | ||||||

| هيراگانا | にっちょうしゅうこうじょうき | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| هانگول | 강화도 조약 | ||||||

| هانچا | 江華島條約 | ||||||

| |||||||

معاهدة كوريا-اليابان 1876 (وتُعرف أيضاً بإسم معاهدة الصداقة الكورية-اليابانية في اليابان و معاهدة جزيرة گانگهوا في كوريا) أُبرِمت بين ممثلي امبراطورية اليابان ومملكة جوسون الكورية في 1876.[1] انتهت المفاوضات في 26 فبراير 1876.[2]

في كوريا، هنگسون دىونگن، الذي شرّع سياسة إغلاق الأبواب أمام القوى الأوروپية، أجبره على التقاعد ابنه الملك گوجونگ وزوجة گوجونگ، الامبراطورة ميونگسونگ. وكانت فرنسا والولايات المتحدة قد قامتا بالفعل بعدة محاولات غير ناجحة لبدء تجارة مع أسرة جوسون في عهد دىونگن. إلا أنه، بعد إزاحته من السلطة، أيـّد العديد من المسئولين الجدد فكرة فتح التجارة مع الأجانب. وأثناء عدم الاستقرار السياسي، طوّرت اليابان خطة لفتح أبواب كوريا وبذل نفوذ عليها قبل أن تتمكن القوى الأوروپية من ذلك. وفي 1875، بدأت اليابان في تنفيذ خطتها: أون'يو، السفينة الحربية اليابانية الصغيرة، أُرسِلت للقيام باستعراض قوة ومسح المياه الساحلية بدون إذن من السلطات الكورية.[3]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية

صعود دىونگن

في يناير 1864، توفي الملك تشولجونگ بدون وريث وارتقى گوجونگ العرش في عمر 12 سنة. إلا أن الملك گوجونگ كان صغيراً وأصبح والد الملك، يي ها-أنگ، الـ دىونگن أو سيد البلاط العظيم، وحكم كوريا بإسم ابنه.[4] المصطلح دىونگن، في الأصل، يشير إلى أي شخص لم يكن فعلاً ملكاً ولكن ابنه تولى العرش.[4] بدأ الدىونگن إصلاحات لتقوية الملكية على حساب طبقة يانگبان.

Even before the nineteenth century, the Koreans had only maintained diplomatic relations with its suzerain China and with neighboring Japan. Foreign trade was mainly limited to China conducted at designated locations along the الحدود الصينية الكورية,[5] and with Japan through the Waegwan in Pusan.[6] By the mid-nineteenth century Westerners had come to refer to Korea as the Hermit Kingdom.[4] The Daewongun was determined to continue Korea's traditional isolationist policy and to purge the kingdom of any foreign ideas that had infiltrated into the nation.[5] أدت الأحداث الكارثية التي وقعت في الصين، بما في ذلك حربا الأفيون الأولى (1839–1842) والثانية (1856–1860)، إلى تقوية عزمه على فصل كوريا عن باقي العالم.[5]

التعدي الغربي

From the early to mid-nineteenth century Western vessels began to make frequent appearances in Korean waters, surveying sea routes and seeking trade.[5] The Korean government was extremely wary and referred to these vessels as strange-looking ships.[5] Consequently, several incidents took place. In June 1832, a ship from the East India Company, the Lord Amherst, appeared off the coast of Hwanghae Province seeking trade but was refused. In June 1845 another British warship, Samarang, surveyed the coast of Cheju-do and Chŏlla province. The following month the Korean government filed a protest with British authorities in Guangzhou through the Chinese government.[5] In June 1846, three French warships dropped anchor off the coast of Chungcheong Province and conveyed a letter protesting persecution of Catholics in the country.[5] In April 1854, two armed Russian vessels sailed along the eastern coast of Hamgyong Province, causing some deaths and injuries among the Koreans they encountered.[مطلوب توضيح] The incident prompted the Korean government to issue a ban forbidding the people of the province from having any contact with foreign vessels. In January and July 1866, ships manned by the German adventurer Ernst J. Oppert appeared off the coast of Chungcheong Province, seeking trade.[5] In August 1866, an American merchant ship, the الجنرال شرمان, appeared off the coast of Pyongan Province, steaming along the Taedong River to the provincial capital of Pyongyang, and asked permission to trade. Local officials refused to enter into trade talks and demanded the ship's departure. A Korean official was then taken hostage aboard the vessel and its crew members fired guns at enraged Korean officials and civilians onshore. The crew then landed ashore and plundered the town in the process killing seven Koreans. The governor of the province Pak Kyu-su ordered his forces to destroy the ship. During the event the General Sherman ran aground on a sandbar and Korean forces burned the ship and killed the ship's entire crew of 23.[7] In 1866 after the execution of several of its Catholic missionaries and Korean Catholics, the French launched a punitive expedition against Korea.[8] Five years later in 1871, the Americans also launched an expedition to Korea.[9] Despite this, the Koreans continued to adhere to isolationism and refused to negotiate to open up the country.[10]

المحاولات اليابانية لتأسيس علاقات مع كوريا

During the Edo period, Japan's relations and trade with Korea were conducted through intermediaries with the Sō family in Tsushima.[11] A Japanese outpost called the waegwan was allowed to be maintained in Tongnae near Pusan. The traders were confined to the outpost and no Japanese were allowed to travel to the Korean capital at Seoul.[11] During the aftermath of the Meiji restoration in late 1868, a member of the Sō daimyō informed the Korean authorities that a new government had been established and an envoy would be sent from Japan.[11] In 1869 the envoy from the Meiji government arrived in Korea carrying a letter requesting to establish a goodwill mission between the two countries;[11] the letter contained the seal of the Meiji government rather than the seals authorized by the Korean Court for the Sō family to use.[12] It also used the character ko (皇) rather than taikun (大君) to refer to the Japanese emperor.[12] The Koreans only used this character to refer to the Chinese emperor, and to the Koreans it implied ceremonial superiority to the Korean monarch which would make the Korean monarch a vassal or subject of the Japanese ruler.[12] The Japanese were however just reacting to their domestic political situation where the Shogun had been replaced by the emperor. The Koreans remained in the sinocentric world where China was at the centre of interstate relations and as a result refused to receive the envoy.[12] The bureau of foreign affairs wanted to change these arrangements to one based on modern state-to-state relations.[13]

حادث گانگهوا

On the morning of September 20, 1875, the Japanese gunboat Un'yō began surveying the Western coast of Korea. The ship reached Ganghwa Island, which had been a site of violent confrontations between the Koreans and foreign forces during the previous decade. The memories of those confrontations were very fresh, and there was little question that the Korean garrison would shoot at any approaching foreign ship. Nonetheless, Commander Inoue ordered a small boat launched and put ashore a party on Kanghwa Island to request water and provisions.[14] The Korean forts opened fire. The Un'yō brought its superior firepower to bear and silenced the Korean guns. After bombarding the Korean fortifications, the shore party torched several houses on the island and exchanged fire with Korean troops. The Japanese were armed with rifles quickly routed the Koreans who carried matchlock muskets, and thirty-five Korean soldiers were left dead.[14] The Un'yo then attacked another Korean fort on Yeongjong Island and withdrew back to Japan.[3]

News of the incident only reached the Japanese government eight days later on September 28, and the following day the government decided to dispatch warships to Pusan to protect Japanese residents there. There were also debates within the government to whether or not to send a mission to Korea to settle the incident.[15]

بنود المعاهدة

استخدمت اليابان دبلوماسية البوارج للضغط على كوريا لتـُوَقـِّع معاهدة غير متكافئة. The pact opened up Korea, as Commodore Matthew Perry's fleet of Black Ships had opened up Japan in 1853. According to the treaty, it ended Joseon's status as a tributary state of the Qing dynasty and opened three ports to Japanese trade. The Treaty also granted the Japanese people many of the same rights in Korea that Westerners enjoyed in Japan, such as extraterritoriality.

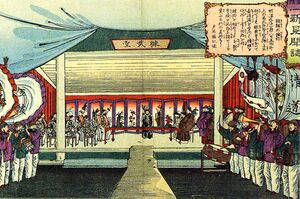

The chief treaty negotiators were Kuroda Kiyotaka, Director of the Hokkaidō Colonization Office, and Shin Heon, General/Minister of Joseon-dynasty Korea.

بنود المعاهدة كانت كالتالي:

- Article 1 stated that Korea was a free nation, "an independent state enjoying the same sovereign rights as does Japan". The Japanese statement is in an attempt to detach Korea once and for all from its traditional tributary relationship with China.

- Article 2 stipulated that Japan and Korea would exchange envoys within fifteen months and permanently maintain diplomatic missions in each country. The Japanese would confer with the Ministry of Rites; the Korean envoy would be received by the Foreign Office.

- Under Article 3, Japan would use the Japanese and Chinese languages in diplomatic communiques, while Korea would use only Chinese.

- Article 4 terminated Tsushima's centuries-old role as a diplomatic intermediary by abolishing all agreements then existing between Korea and Tsushima.

- In addition to the open port of Pusan, Article 5 authorized the search in Kyongsang, Kyonggi, Chungcheong, Cholla, and Hamgyong provinces for two more suitable seaports for Japanese trade to be opened in October 1877.

- Article 6 secured aid and support for ships stranded or wrecked along the Korea or Japanese coasts.

- Article 7 permitted any Japanese mariner to conduct surveys and mapping operations at will in the seas off the Korean Peninsula's coastline.

- Article 8 permitted Japanese merchants residence, unhindered trade, and the right to lease land and buildings for those purposes in the open ports.

- Article 9 guaranteed the freedom to conduct business without interference from either government and to trade without restrictions or prohibitions.

- Article 10 granted Japan the right of extraterritoriality, the one feature of previous Western treaties that was most widely resented in Asia. It not only gave foreigners a free rein to commit crimes with relative impunity, but its inclusion implied the grantor nation's system of law was either primitive, unjust, or both.

الأعقاب

The following year saw a Japanese fleet led by Special Envoy Kuroda Kiyotaka coming over to Joseon, demanding an apology from the Korean government and a commercial treaty between the two nations. The Korean government decided to accept the demand, in hope of importing some technologies to defend the country from any future invasions.

However, the treaty would eventually turn out to be the first of many unequal treaties signed by Korea; It gave extraterritorial rights to Japanese citizens in Korea, and forced the Korean government to open 3 ports to Japan, specifically Busan, Incheon and Wonsan. With the signing of its first unequal treaty, Korea became vulnerable to the influence of imperialistic powers; and later the treaty led Korea to be annexed by Japan.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

- دليل المقالات المتعلقة بكوريا

- تاريخ كوريا

- Japan–Korea disputes

- General Sherman incident (1866)

- الحملة الفرنسية ضد كوريا (1866)

- تجريدة الولايات المتحدة إلى كوريا (1871)

- حادث جزيرة گانگهوا (1875)

- استسلام (معاهدة)

الهامش

- ^ Chung, Young-lob. (2005). Korea Under Siege, 1876–1945: Capital Formation and Economic Transformation, p. 42., p. 42, في كتب گوگل; excerpt, "... the initial opening of Korea's borders to the outside world came in the form of the Korea-Japan Treaty of Amity (the so-called Ganghwa Treaty)."

- ^ Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, D.C., 1921–1922. (1922). Korea's Appeal, p. 33., p. 33, في كتب گوگل; excerpt, "Treaty between Japan and Korea, dated February 26, 1876."

- ^ أ ب Key-Hiuk., Kim (1980). The last phase of the East Asian world order : Korea, Japan, and the Chinese Empire, 1860–1882. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 205–209, 228, 231. ISBN 0520035569. OCLC 6114963.

- ^ أ ب ت Kim 2012, p. 279.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Kim 2012, p. 281.

- ^ Seth 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Kim 2012, p. 282.

- ^ Kim 2012, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Kim 2012, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Kim 2012, p. 284.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Duus 1998, p. 30.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Duus 1998, p. 31.

- ^ Jansen 2002, p. 362.

- ^ أ ب Duus 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Duus 1998, p. 44.

المراجع

- Duus, Peter (1998). The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea. University of California Press. ISBN 0-52092-090-2.

- Keene, Donald (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12341-8.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. New York: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00024-8.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6740-0334-9.

- Jansen, Marius B. (1995). The Emergence of Meiji Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5214-8405-7.

- Seth, Michael J. (2011). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-742-56715-3.

- Sims, Richard (1998). French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854–95. Psychology Press. ISBN 1-87341-061-1.

- Chung, Young-lob. (2005). Korea Under Siege, 1876–1945: Capital Formation and Economic Transformation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517830-2; OCLC 156412277

- Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, D.C., 1921–1922. (1922). Korea's Appeal to the Conference on Limitation of Armament. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 12923609

- United States. Dept. of State. (1919). Catalogue of treaties: 1814–1918. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 3830508

للاستزادة

- McDougall, Walter (1993). Let the Sea Make a Noise: Four Hundred Years of Cataclysm, Conquest, War and Folly in the North Pacific. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 9780380724673; OCLC 152400671

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing كورية-language text

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from May 2019

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- 1876 في اليابان

- 1876 في كوريا

- العلاقات الكورية اليابانية

- المعاهدات غير المتكافئة

- معاهدات امبراطورية اليابان

- معاهدات أسرة جوسون

- معاهدات 1876

- أحداث فبراير 1876