مصطبة

mastaba ( /ˈmæstəbə/,[1] /ˈmɑːstɑːbɑː/ or /mɑːˈstɑːbɑː/), also mastabah, mastabat or pr-djt (meaning "house of stability", "house of eternity" or "eternal house" in Ancient Egyptian) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks. These edifices marked the burial sites of many eminent Egyptians during Egypt's Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. In the Old Kingdom epoch, local kings began to be buried in pyramids instead of in mastabas, although non-royal use of mastabas continued for over a thousand years. Egyptologists call these tombs mastaba, from the Arabic word مصطبة (maṣṭaba) "stone bench".[2]

التاريخ

The afterlife was important in the religion of ancient Egyptians. Their architecture reflects this, most prominently by the enormous amounts of time and labour involved in building tombs.[3] Ancient Egyptians believed the soul could live only if the body was fed and preserved from corruption and depredation.[4]

Starting in the Predynastic era and continuing into later dynasties, the ancient Egyptians developed increasingly complex and effective methods for preserving and protecting the bodies of the dead. They first buried their dead in pit graves dug from the sand with the body placed on a mat, usually along with some items believed to help them in the afterlife. The first tomb structure the Egyptians developed was the mastaba, composed of earthen bricks made from soil along the Nile. It provided better protection from scavenging animals and grave robbers. As the remains were not in contact with the dry desert sand, natural mummification could not take place; therefore the Egyptians devised a system of artificial mummification.[5] Until at least the Old Period or First Intermediate Period, only high officials and royalty were buried in these mastabas.[6]

البنية

The term mastaba comes from the Arabic word for "a bench of mud".[7] When seen from a distance, a flat-topped mastaba does resemble a bench. Historians speculate that the Egyptians may have borrowed architectural ideas from Mesopotamia, since at the time they were both building similar structures.[8]

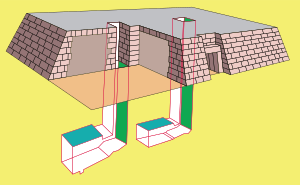

The above-ground structure of a mastaba is rectangular in shape with inward-sloping sides and a flat roof. The exterior building materials were initially bricks made of the sun-dried mud readily available from the Nile River. Even after more durable materials such as stone came into use, all but the most important monumental structures were built from mudbricks.[9] Mastabas were often about four times as long as they were wide, and many rose to at least 30 feet in height. They were oriented north–south, which the Egyptians believed was essential for access to the afterlife. The above-ground structure had space for a small offering chapel equipped with a false door. Priests and family members brought food and other offerings for the soul, or ba, of the deceased, which had to be maintained in order to continue to exist in the afterlife.

Inside the mastaba, the burial chambers were cut deep, into the bedrock, and were lined with wood.[10] A second hidden chamber called a serdab (سرداب), from the Persian word for "cellar",[11] was used to store anything that may have been considered essential for the comfort of the deceased in the afterlife, such as beer, grain, clothes and precious items.[12] The mastaba housed a statue of the deceased that was hidden within the masonry for its protection. High up the walls of the serdab were small openings that would allow the ba to leave and return to the body (represented by the statue); Ancient Egyptians believed the ba had to return to its body or it would die. These openings "were not meant for viewing the statue but rather for allowing the fragrance of burning incense, and possibly the spells spoken in rituals, to reach the statue".[13]

التطور المعماري

The mastaba was the standard type of tomb in pre-dynastic and early dynastic Egypt for both the pharaoh and the social elite. The ancient city of Abydos was the location chosen for many of the cenotaphs. The royal cemetery was at Saqqara, overlooking the capital of early times, Memphis.[14]

Mastabas evolved over the early dynastic period. During the 1st Dynasty, a mastaba was constructed simulating house plans of several rooms, a central one containing the sarcophagus and others surrounding it to receive the abundant funerary offerings. The whole was built in a shallow pit above which a brick superstructure covering a broad area. The typical 2nd and 3rd Dynasty mastabas was the 'stairway mastaba', the tomb chamber of which sank deeper than before and was connected to the top with an inclined shaft and stairs.[14]

Even after pharaohs began to construct pyramids for their tombs in the 3rd Dynasty, members of the nobility continued to be buried in mastaba tombs. This is especially evident on the Giza Plateau, where at least 150 mastaba tombs have been constructed alongside the pyramids.[15]

In the 4th Dynasty (c. 2613 to 2494 BC), rock-cut tombs began to appear. These were tombs built into the rock cliffs in Upper Egypt in an attempt to further thwart grave robbers.[16] Mastabas, then, were developed with the addition of offering chapels and vertical shafts. 5th Dynasty mastabas had elaborate chapels consisting of several rooms, columned halls and 'serdab'. The actual tomb chamber was built below the south-end of mastaba, connected by a slanting passage to a stairway emerging in the center of a columned hall or court.

Mastabas are still well attested in the Middle Kingdom. Here they had a revival. They were often solid structures with the decoration only on the outside.[17]

By the time of the New Kingdom (which began with the 18th Dynasty around 1550 BC), "the mastaba becomes rare, being largely superseded by the independent pyramid chapel above a burial chamber".[18]

أمثلة

انظر أيضاً

- Cemetery GIS

- Meidum

- Architecture of Palestine: mastabeh or mastaba as raised, indoor or outdoor "unsoiled" area in traditional Palestinian architecture[19]

المراجع

- ^ "Mastaba: definition". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Mastaba Tomb of Perneb". Met Museum. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Hamlin, Talbot (1954). Architecture through the Ages. New York: Putnam. p. 30.

- ^ Badawy, Alexander (1966). Architecture in Ancient Egypt and the Near East. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 46.

- ^ Ancient Egypt and the Near East. Cambridge: MIT Press. 1966. p. 7.

- ^ BBC. "mastabas". BBC. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Gardiner, A. (1964). Egypt of the Pharahos. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 57 n7.

- ^ Gascone, Bamber. "History of architecture". History of the world. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ R., C. L. (1913). "A Model of the Mastaba-Tomb of Userkaf-Ankh". Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 8 (6): 125–130. doi:10.2307/3252928. JSTOR 3252928.

- ^ BBC. "Mastabas". bbc. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Bard, K. A. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415185899.

- ^ Lewis, Ralph. "Burial practices, and Mummies". Rosicrucian Museum. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Arnold, Dorothea (1999). When the Pyramids were Built: Egyptian Art of the Old Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 12. ISBN 978-0870999086.

- ^ أ ب Fletcher, Banister (1996). A History of Architecture (20th ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0750622677.

- ^ Davis, Ben (1997). "The Future of the Past". Scientific American. 277 (2): 89–92. JSTOR 24995879.

- ^ R., L. E. (1910). "Two Mastaba Chambers". Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin. 8 (45): 19–20. JSTOR 4423469.

- ^ Arnold, D. (2008): Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht, Egyptian Expedition XXVIII, Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York ISBN 9781588391940, S. 26-30

- ^ Badawy, Alexander (1966). Architecture in Ancient Egypt and the Near East. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 51.

- ^ Awad, Shaden, The Peasant House: Contemporary Meanings, Syntactic Qualities and Rehabilitation Challenges., Graz University of Technology 2010. Accesses 24 Feb 2021.

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- مصطبات

- Types of monuments and memorials

- مصر القديمة

- Burial monuments and structures

- Ancient Egyptian architecture

- Egyptian inventions