مسجد گيان واپي

| مسجد گيان واپي Gyan Vapi Mosque | |

|---|---|

مسجد گيان واپي | |

| الموقع | |

| الموقع | ڤرناسي، الهند |

| الولاية | أتر پردش |

| الإحداثيات الجغرافية | 25°18′40″N 83°00′38″E / 25.311229°N 83.010461°E |

| العمارة | |

| النمط المعماري | عمارة مغل الهند (جزء من العمارة الإسلامية-الهندية) |

| المواصفات | |

| القباب | 3 |

| المآذن | 2 |

گيان واپي (Gyanvapi Mosque) يقع في باناراس، أتر پردش، الهند. شيده أورنگ زيب في عام 1669 عند هدم معبد شيڤا الأقدم.[1]

عصر ما قبل المسجد

معبد ڤيشوِشوار

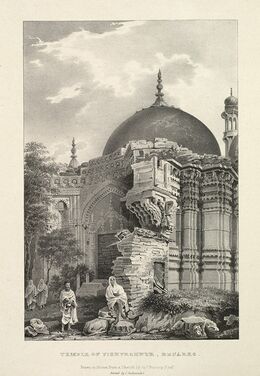

كان الموقع به معبد ڤيشويشوار مخصص للإله الهندوسي شيڤا.[5] قام ببناءه تودار مال، أحد رجال البلاط الملكي ووزير أكبر، بالاشتراك مع نارايانا بهاتا، أحد العلماء البارزين من البراهمة في باناراس من ولاية ماهاراشترا، في أواخر القرن السادس عشر.[6][7] وصف محمود بلخي، هيكل المعبد خلال زيارته عام 1630، وصف مجمع المعبد {{efn|به مدرسة ودار عبادة ونزل وحوالي ثمانين منزلاً؛ وكان حشد من ثلاثين الفا حاضرا يوم زيارته.[8] بأنه مبني من الحجر والطوب يبلغ ارتفاعه مائة وثلاثين ياردة، ويمتد عبر محيط مائة ياردة.[8] ليكون من "لالا سينغ" ، كما كان الكاتب بهيمسن ، يكتب في أوائل القرن الثامن عشر؛ وهكذا، يبدو أن ڤير سينغ ديو بونديلا، كان شريكًا مقربًا من جهانكير، كان راعيًا في أوائل القرن السابع عشر.[8]

يفترض المؤرخ المعماري مادهوري ديساي أن المعبد كان نظام تقاطع إيوان - استعارة من العمارة المغولية - مع أقواس مدببة بارزة. كان به حجر خارجي منحوت.[9] ساهم المعبد في جعل بانارس مركز متبجح للتجمع البراهميني، وجذب العلماء عبر شبه القارة الهندية. ولاية ماهاراشترا، للفصل في مجموعة من النزاعات المتعلقة بالقانون الديني الهندوسي.[8]

تاريخ ما قبل المسجد

يناقش العلماء ما قد يكون موجودًا في الموقع قبل هذا المعبد.[10] يعتبر هذا التاريخ محل نزاع على نطاق واسع من قبل السكان المحليين الهندوس والمسلمين.[11][12] يشير دساي إلى التواريخ المتعددة للمعبد الأصلي والتوترات الناشئة عن موقع گيان واپي لتشكيل التضاريس المقدسة للمدينة بشكل أساسي.[11]

الروايات الحديثة عن تاريخ المسجد كما رواها الهندوس،[أ] وتتمحور حول سلسلة من التدمير المتكرر وإعادة بناء المعبد الأصلي الذي يقع على النقيض من خلود لينگام.[11] يُزعم أن المعبد الأصلي، الموجود في الموقع الحالي للمسجد، قد اقتلعه قطب الدين أيبك في 1193/1194، عند هزيمة رجا جاياشاندرا من [[قنوج ]]؛ شُيِّد مسجد راضية مكانه بعد سنوات قليلة.[14][15] T أعاد تاجر غوجاراتي بناء المعبد في عهد التوميش (1211-1266 م) ليتم هدمه على يد حسين شاه شرقي (1447–1458) أو سيكندر لودي (1489) –1517).[15] أثناء حكم أكبر ،أعاد مان سينغ الأولرجا مان سينغ إعادة بناء المعبد،[ب] لكنها وقعت مرة أخرى ضحية لتعصب أورنگ زيب الديني المتشدد.[12]

صحة الوقائع التاريخية

اكتشفت ديانا إيك سجلات العصور الوسطى لتأكيد المفاهيم الهندوسية لمباني عدي ڤيشڤيشوارا كونها الموطن الأصلي لللينگام؛ ومع ذلك، فقد انتقد العلماء استخدام إيك غير السياقي لمصادر العصور الوسطى.[16][17][ت] وجد هانز ت. باكر أن المعبد الذي دُمر عام 1194 يقع بالفعل في مناطق گيان واپي الحالية ولكنه مخصص لأفيموكتيشوارا ؛ في وقت ما في أواخر القرن الثالث عشر، استعاد الهندوس موقع گيان واپيالشاغر لمعبد ڤيشويشوار منذ أن احتل مسجد رازيا "تل ڤيشويشوار ".[20] سيتم تدمير هذا المعبد الجديد لاحقًا علي يد سلطنة جانپور، على ما يبدو لتزويد مواد البناء للمساجد في عاصمتهم الجديدة.[20]

في المقابل، ترفض ديساي، في قراءتها لأدب العصور الوسطى، وجود أي معبد ڤيشويشوار في أوائل العصور الوسطى باناراس. ترى هي وعلماء أخرين أنه كان فقط في كاشيكاند.[ث] وأن ڤيشويشوار يظهر على أنه الإله الرئيسي للمدينة لأول مرة وحتى ذلك الحين، ظل لعدة قرون واحدة من بين المواقع المقدسة "العديدة" في بانارس.[21][14][ج] خلف ڤيشويشوار أڤيموكتيشوارا ليصبح الضريح الرئيسي للمدينة فقط بعد رعاية مستمرة من المغول، بدءًا من أواخر القرن السادس عشر.[23] يُنظر إلى الإدعاءات الهندوسية على أنها اللبنات الأساسية لسرد مادي حول تعرض الحضارة الهندوسية للقمع المستمر من قبل الغزاة المسلمين، والتي تم تعزيزها من خلال الأجهزة الاستعمارية لإنتاج المعرفة.[24]

الإنشاء

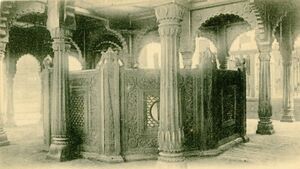

في سبتمبر 1669، أمر أورنگ زيب بهدم المعبد؛[21] تم بعدها بناء مسجد محله، ويعتقد أن أورنگ زيب هو من قام ببنائه.[25][26][ح] صُممت الواجهة جزئيًا على غرار مدخل تاج محل؛ تُركت قاعدة المعبد دون أن مسها إلى حد كبير لتكون بمثابة فناء للمسجد، وتم تحويل الجدار الجنوبي - جنبًا إلى جنب مع الأقواس المقوسة والقوالب الخارجية والتورانات - إلى جدار للقبلة.[1][29][30][17] أُنقذت المباني الأخرى في المنطقة.[29]

تشير الروايات الشفوية إلى أنه على الرغم من التدنيس، فقد سُمح للكهنة البراهمة بالإقامة في مباني المسجد وممارسة امتيازاتهم في شعائر الحج الهندوسي.[29] ظلت بقايا المعبد، وخاصة القاعدة، كمركز شهير للحجاج الهندوس.[31] أصبح المسجد يعرف باسم مسجد علامة گيري- على اسم أورنگ زيب —[32] ولكن بمرور الوقت، تم تبني الاسم الحالي بلغة مشتركة مشتقة من المسطح المائي المقدس المجاور — گيان واپي ("بئر المعرفة") —[6] والذي، في جميع الاحتمالات، سبق معبد ڤيشوى شوار.[33][خ]

الدوافع

يعزو العلماء أن الدافع الأساسي لهدم أورنگ زيب هو أسباب سياسية ولبيس التعصب الديني.[26] يشير "تاريخ أكسفورد العالمي للإمبراطورية" إلى أنه في حين يمكن تفسير الهدم على أنه علامة على "الميول الأرثوذكسية" لأورنگ زيب، فقد لعبت السياسات المحلية دورًا مؤثرًا وكانت سياساته تجاه الهندوس وأماكن عبادتهم "متنوعة ومتناقضة، بدلاً من الحياد المستمر". يجد ديساي أن سياسات أورنگ زيب المعقدة والمتناقضة في كثير من الأحيان يمكن "تحليلها بدقة أكبر في ضوء إجباره الشخصي وأجندته السياسية، بدلاً من كونها تعبيرات عن التعصب الديني".[5]

لاحظت كاثرين آشر، مؤرخة العمارة الهندية الإسلامية، أن زميندار (ملاك الأرض) في باناراس تمردوا بشكل متكرر ضد أورنگ زيب، لكن البراهمة المحليون اتهموا أيضاً بالتدخل في التعاليم الإسلامية.[1] وبناءً على ذلك، قالت إن الهدم كان رسالة سياسية من حيث أنه كان بمثابة تحذير لزعماء الزميندار والزعماء الدينيين الهندوس، الذين كان لهم نفوذ كبير في المدينة؛[1] واتفق كل من سينثيا تالبوت، رتشارد إيتون،[34] ساتش تشاندرا وأودري تروتشك على نفس الدوافع.[35] يسلط أوهالون الضوء على أن المعبد قد هُدم في وقت كان الصراع مع المراثا في ذروته.[36] ومع ذلك ، يختلف أندريه وينك حول غياب الدوافع الدينية.[37]

للتسجيل، منح أورنگ زيب الحماية والرعاية للعديد من المعابد والگات والرياضيات، بما في ذلك في باناراس، قبل الهدم وبعده. يدعم إيان كوبلاند وآخرون إقتدار علم خان الذي خلص إلى أن أورنگ زيب قد بنى عددًا من المعابد أكثر مما دمره.[38]

المزاعم المضادة من المسلمين

كتبت ماري سيرل تشاترجي في عام 1993، أنها تجد أن معظم المسلمين المحليين يرفضون فكرة أن أورنگ زيب قد هدم المعبد بدافع التعصب الديني. وتضمنت نظرايتها:[39]

- كان المبنى الأصلي عبارة عن هيكل لعقيدة الدين الإلهي الذي انهار من تلقاء نفسه أو دمره أورنگ زيب، بسبب عداءه لمدرسة فكر "أكبر" المهرطقة.

- كان المبنى الأصلي عبارة عن معبد ولكن دمره تاجر هندوسي من جونپور يُدعى جنان تشاند، نتيجة قيام الكهنة بنهب وانتهاك وقتل إحدى قريباته من الإناث.

- * شكل طفيف حيث كان أورنگ زيب هو الذي دمر المعبد بعد أن عانت إحدى قريبات الضابط المرافق من هذا المصير.[د]

- كان المبنى الأصلي عبارة عن معبد لكنه دمر في أعمال شغب طائفية أثارها الهندوس المحليون

- * كنج أرسادي - مجموعة من أقوال أرساد بدر الحق (1637-1701) عن بنارس، جُمعت عام 1721 [40] - تلاحظ أن أحد القديسين سماها قام "شاه ياسين" بهدم "المعبد الكبير" (يُفترض عمومًا أنه فيشويشوار)، بمساعدة النساجين المسلمين المحليين، انتقامًا من الهندوس الذين هدموا مسجدًا.[41]

يبدو أن الهندوس قد شاركوا في عمليات هدم متكررة لمسجد قيد الإنشاء، مما أدى إلى مواجهة عنيفة بين المجتمعين وأدى إلى مقتل مسلمين. وهكذا، تم دفع ياسين إلى تدمير العديد من المعابد على الرغم من معارضة الإدارة المحلية التي أشارت إلى عدم وجود موافقة إمبراطورية.[41]

- كان المبنى الأصلي عبارة عن معبد وقد دمره أورنگ زيب ولكن فقط لأنه كان بمثابة مركز للتمرد السياسي.

افترض مولانا عبد السلام نعماني (المتوفى 1987)، الإمام السابق لمسجد گيان واپي، أن المسجد قد تم تشييده قبل فترة طويلة من حكم أورنگ زيب. يدعي أدلة على شاه جهان أنه بدأ مدرسة في المسجد في 1638-1639 .[42][43] تدعم لجنة إدارة المسجد نعماني وتؤكد أن كل من معبد كاشي ڤيشواث (الجديد) ومسجد گيان واپي قد شيدهما أكبر، تماشيًا مع روح التسامح الديني.[44] اعتبارًا من عام 2021، رفض المسلمون المحليون رفضًا قاطعًا قيام أورنگ زيب بهدم أي معبد لتكليف المسجد.[45]

كان هناك القليل من المشاركة مع هذه الادعاءات في المنح الدراسية التاريخية؛ [ذ] يقرأ ديساي حجج نوماني على أنها "إعادة كتابة استراتيجية للتاريخ" ناشئة عن الطبيعة الهندوسية المهيمنة للخطاب في بيناراس ما بعد الاستعمار.[48]

الهند بأواخر عصر المغل

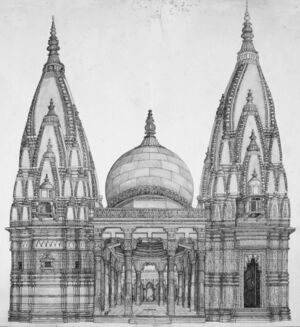

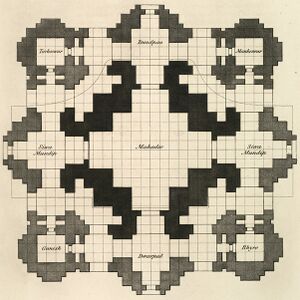

عام 1698، طلب بيشان سينغ، حاكم الكاشواها في عنبر، عملائه مسح المدينة - بدلاً من المناظر الطبيعية الطقسية - وجمعوا تفاصيل حول الادعاءات والخلافات المختلفة المتعلقة بهدم المعبد؛ كانت خرائطهم ('tarah') واضحة في وجود مسجد گيان واپي على موقع معبد ڤيشويشوار المفكك.[49] تم ترسيم قاعدة المعبد مع بئر گيان واپي (بئر البركة) بشكل منفصل.[49][ر] اشترت محكمة عنبر أراضي كبيرة حول مناطق گيان واپي، بما في ذلك من السكان المسلمين، بهدف إعادة بناء المعبد دون هدم المسجد لكنها فشلت.[50] في النهاية، تم تشييد "معبد آدي-ڤيشويشوار" بمبادرة من سواي جاي سينغ الثاني، خليفة بيشان سينغ،[49] على بعد 150 ياردة تقريباً أمام المسجد.[51] اقتبس تصميم البناء من العمارة المغولية المعاصرة - حيث وجد ديساي أن التصنيف يشبه مقبرة المغل أكثر من كونه معبد - في ما يعتبره العلماء عروض عامة للرعاية الإمبراطورية.[52][53]

بحلول أوائل القرن الثامن عشر، كانت بانار تحت سيطرة نواب لكناو الفعلية.[54] مع ظهور شركة الهند الشرقية وسياسات الضم الشديدة المتزايدة، بدأ العديد من الحكام من جميع أنحاء البلاد - وحتى النخب الإدارية - في الاستثمار في Brahminising Banaras، للمطالبة بالسلطة الثقافية في أوطانهم.[54] أصبح المراثا، على وجه الخصوص، صريحون للغاية بشأن الظلم الديني على يد أورنگزيب واقترح نانا فادناڤيس هدم المسجد وإعادة بناء معبد ڤيشويشوار.[55][56] عام 1742، اقترح مالار راو هولكار مسارًا مشابهًا للعمل. [55] على الرغم من جهودهم المستمرة، لم تتحقق هذه الخطط بسبب العديد من التدخلات - نواب لكناو كانوا خصومهم السياسيين، والبراهمة المحليين الذين خافوا من غضب بلاط المغل، والسلطات البريطانية التي كانت تخشى اندلاع التوترات الطائفية.[14][57]

في أواخر القرن الثامن عشر، عندما اكتسبت شركة الهند الشرقية سيطرة مباشرة على البنارا للإطاحة بالنواب، قام خليفة مالار راو (وزوجة ابنه) اہلیابائی ہولکر ببناء معبد كاشي ڤيشوانات الحالي إلى الجنوب مباشرة من المسجد، ومع ذلك، كان تكوينه المكاني مختلف بشكل ملحوظ وكان غير متسق من الناحية الطقسية.[58][ز] مع الاعتقاد بأن lingam الأصلي كان مخبأ من قبل الكهنة داخل گيان واپي أثناء غارة أورنگزيب، فإن القاعدة ستجذب تفانيًا أكبر من المعبد لأكثر من قرن.[54][31]

الراج البريطاني

Under the British Raj, the Gyan Vapi precincts, which was once the subject of whimsical Mughal politics, got transformed into a site of perennial contestation between local Hindus and Muslims spawning numerous legal suits and even, riots.[59][60] A new generation of aristocrats and well-to-do traders took over the role exclusively played by petty rulers in late-Mughal India in controlling the ritual life of the city, most often under the guise of urbanization. Says Desai, that the construction of mosque had sought to air an "explicitly political and visual" assertion about the Mughal command over the city’s religious sphere but instead, "transmuted Vishweshwur into the undisputed fulcrum of the city’s ritual landscape".[29]

The 1809 riot, widely believed to be first significant riot in N. India under Company rule, hastened the growth of competitive communalism in Banaras.[61] An attempt by the Hindu community to construct a shrine on the "neutral" space between the Gyanvapi Mosque and the Kashi Vishwanath Temple heightened tensions.[62] Soon enough, the festival of Holi and Muharram fell on the same day and confrontation by revelers fomented a riot.[62] A Muslim mob killed a cow — sacred to Hindus — to spoil the sacred water of the Gyanvapi well; a Hindu mob attempted to arson the Gyanvapi Mosque and then, demolish it.[63] Several deaths were reported and property damage ran into lacs, before the British administration quelled the riot.[62]

Visiting in September 1824, Reginald Heber found the plinth to be more revered than Ahilyabai's temple and filled with priests and devotees; the "well", fed by a subterranean channel of the Ganges, featured a stair for the devotees to descent and take a bath.[64] Four years later, Baiza Bai, widow of the Maratha ruler Daulat Rao Scindhia, constructed a pavilion around the well — reducing it in size —, and erected a colonnade to support a roof, pursuant to a proposal raised by member of a Peshwa family.[25][29] The colonnade was based on the Gyan Mandapa, mentioned in Kashikhand but the architectural style was borrowed from contemporary Mughal Baradaris.[س] To its east, was a statue of Nandi, which had been gifted by the Rana of Nepal.[66] To further east, a temple of Mahadeva was constructed by the Rani of Hyderabad.[66] In the south, two small shrines —one of marble, and the other of stone— existed.[66] The first legal dispute seem to have arose in 1854, when the local court rejected a plea to install a new idol in the complex.[67][ش] The same year, a Bengali pilgrim noted that Muslim guards were to be "either bribed or hoodwinked" to access the precincts.[59] M. A. Sherring[ص], writing in 1868, noted the Hindus to have claimed the plinth as well as the southern wall; the Muslims were allowed to exert control over the mosque but quite reluctantly, and permitted to only use the side entrance.[68][ض] A peepal tree overhanging the gateway was also venerated, and Muslims were not allowed to "pluck a single leaf from it."[59] In 1886, adjudicating on a dispute about illegal constructions, the District Magistrate held that unlike the mosque proper, which had belonged to the Muslims exclusively, the enclosure was a common space thereby precluding any unilateral and innovative use.[70]>[67] This principle would continue to decide multiple cases in the next few decades.[67][ط]

Edwin Greaves, visiting the site in 1909, found that the mosque was "not greatly used", and remained an "eyesore" to the Hindus.[71] His description of the pavillion paralleled Sherring's.[72] The well commanded significant devotion too — pilgrims received its sacred water from a priest, who sat on an adjoining stone-screen; the well was also covered with iron-rails to prevent suicides and devotees were not allowed direct access to the water.[73] In the meanwhile, legal disputes continued unabated.[67][ظ]

In 1929 and 1930, the cleric was cautioned into not letting the crowd overflow into the enclosure on the occasion of Jumu'atul-Wida, lest Hindu pilgrims face inconvenience.[67] Subsequently, in January 1935, the mosque committee unsuccessfully demanded before the District Magistrate that the restriction on crowd-overflow be waived off; in October, it was demanded, yet unsuccessfully, that Muslims be allowed to offer prayers anywhere in the complex.[67] In December 1935, local Muslims attacked the Police after being prevented from offering prayers outside of the mosque proper, injuring several officials.[75] This gave way to a law-suit urging that the entire complex be treated as an integral part of the mosque — a waqf property — by customary rights, if not by legal rights; the contention was rejected by the lower Court in August 1937[ع] and an appeal was dismissed by the Allahabad High Court with costs, in 1941.[67][غ]

الهند المستقلة

The site continues to remain volatile — Dumper finds it to be the "focus of religious tension" in the town.[76] Access to the mosque remains prohibited for non-Muslims, photography is prohibited, approaching alleys have light police-pickets (alongside RAF units), the walls are fenced with barbed wire, and a watchtower exists too.[17][48] The mosque is neither well-used nor embedded enough in the cultural life of the city.[17] On the eve of the 2004 Indian general election, a BBC report noted over a thousand policemen to have been deployed around the site.[77]

Beginning 1984, the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and other elements of Sangh Parivar engaged in a nation-wide campaign to reclaim mosques which were constructed by demolishing Hindu temples including the Gyanvapi.[17][78] In 1991, a title-dispute suit[ف] was filed by three local Hindus in the Varanasi Civil Court on behalf of three Hindu deities —Shiva, Shrngar Gauri, and Ganesh— for handing over the entire site to Hindu community to facilitate reconstruction of the temple; AIM, acting as one of the defendants, contended that the petition contravened the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act (henceforth PoW), which had expressly prohibited Courts from entertaining any litigation that sought to convert places of worship.[80][79] In the meanwhile, tensions increased in the wake of demolition of the Babri mosque in December 1992[ق] but Bharatiya Janata Party leaders, including those who had supported the demand for "reclaiming" Babri mosque, opposed VHP's demand since the mosque was actively used.[81] Further, VHP leaders issued multiple calls across the mid-90s for Hindus to congregate in large numbers on the occasion of Maha Shivaratri and worship the Shrngar Gauri image at the southern wall; public response was poor and no fracas ensured courtesy a proactive administration.[82]

Hearings commenced in the Civil Court from June 1997, and in 1998, the suit was held to be barred by the PoW act.[79] Three revision petitions were filed before the district court, by both the plaintiff and defendants, which were merged and the civil court was ordered to adjudicate the dispute, afresh.[79][83] The mosque management committee successfully challenged this allowance in the Allahabad High Court, who stayed the proceedings indefinitely.[80] After a limbo of 22 years, the advocate of the 1991 petition refiled another plea[ك] requesting for an ASI survey of the mosque-complex on the same grounds.[80][84] AIM, acting as the defendant, rejected that Aurangzeb had demolished any temple to construct the mosque.[85]

In March 2019, a few local residents were caught burying a small statue of Nandi near the north wall of the Gyanvapi mosque.[86]

On 8 April 2021, the city-court ordered the Archaeological Survey of India to conduct the requested survey.[80] Further, a five-member committee of archaeologists —with two members from the "minority community"— was constituted to determine whether any temple existed at the site, prior to the mosque.[80][85] Most commentators opined the court's ruling to run up against the PoW act and other matters of law.[87] The very same day, a challenge was filed by the defendants in the Allahabad High Court.[88] On 9 September, the High Court ruled in favor of the defendants; the survey was indefinitely stayed and the judgement criticized for breach of judicial decorum.[88]

انظر أيضاً

- مساجد شهيرة أخرى في ڤرناسي: مسجد جانج-إ-شهيدان ومسجد چوكامبا

- تحويل أماكن العبادة غير الإسلامية إلى مساجد

ملاحظات

- ^ Pilgrims visiting the present Kashi Vishwanath Temple are informed with such a narrative.[13] روجت الكتب المدرسية المحلية في التسعينيات مثل هذه القراءة لماضي المسجد أيضًا.[12]

- ^ orthodox Brahmins apparently chose to boycott the temple, since Man Singh's daughter was married to Islamic rulers.[15]

- ^ Dumper notes Diana Eck to be a highly respected scholar on Sanskrit and Banaras but finds her history to be "extraordinarily confusing, moving from rhetorical storytelling to historical fact".[18] يرى دساي أن حساب إيك يسير بالتوازي مع قطع المستشرقين في القرن التاسع عشر، حيث تمتزج "الآثار الأسطورية" لباناراس بسلاسة مع "أوصاف المدينة المعاصرة".[19]

- ^ A part of Skanda Purana; widely considered to be the most authoritative non-secular text on the conception of the city.

- ^ Different 'nibandha' commentators across the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries zeroed in on different temples and sought to re-define the sacred space of Kashitirtha in its terms .[22]

- ^ Maasir-i-Alamgiri —a hagiographic account of Aurangzeb, penned after his death, by Saqi Mustaid Khan— only records the destruction of the temple:[27]

ومن بين مصادر الخان أرشيفات الدولة. ومع ذلك، لم يقدم اقتباسات. لاحظ خافي خان، كاتب سيرة معاصر آخر لأورنگ زيب، نقص المصادر المكتوبة لأحداث ما بعد عام 1667، وبالتالي الحاجة إلى الاعتماد على الذاكرة.[28]It was reported that, according to the Emperor’s [Aurangzeb] command, his officers had demolished the temple of Viswanath at Kashi.

- ^ Legends hold that Shiva had dug it himself to cool the lingam.[6]

- ^ This finds a mention in Bhogaraju Pattabhi Sitaramayya in his prison diary; an acquaintance, who had a contemporary manuscript in support, died of a sudden.

- ^ ومع ذلك، تلاحظ ماري سيرل شاتيرجي مؤرخًا بارزًا من جامعة باناراس الهندوسية (جي دي بهاتناغار) لرفض قيام أورنگ زيب بتدمير معبد.[46] Searle-Chatterjee herself refuses to discuss the historical validity of competing narratives, noting - "The historical issues are irrelevant, since it is dear that whatever the facts were, accounts of the origin of the central ruin are now functioning as symbolic narrative, providing a charter for contemporary attitudes and behavior."[47]

- ^ These maps also noted the edges of the rectangular mosque-precinct to be lined up with the residences of Brahmin priests.

- ^ The precise year of construction is not known. It already existed by 1781, when Warren Hastings commissioned the construction of a gateway.

- ^ Lazeratti notes, from conservations with Vyas family, that Muslims were subsequently prevented from accessing the water for purposes of wudu etc.[65] The current wudukhana appears to have been constructed sometime hence.

- ^ A similar dispute reached the Court in 1858 but was settled in favor of the Hindus.

- ^ An amateur archaeologist, Sherring took to establishing Benaras as a Buddhist city of yore that had fallen to Brahminism, before felling to Muslims. He noted the presence of "Buddhist pillars" within the Gyanvapi Mosque, too.Such an assertion was thought to be a potent antidote to the fashioning of Benaras as an ageless site of pilgrimage for Hindus, which hindered Missionaries' efforts in converting natives. Also, if Buddhism could fell to Hinduism after centuries of glory, so would Hinduism to Christianity.

- ^ Local Muslims had once built a gateway in the middle of the platform in front of the mosque, but were not allowed to use it amidst severe Hindu discontent.[69]

- ^ In 1887, an application by two local Muslims to open a shop at the complex-perimeter was rejected; in 1889, construction of a stone bench was allowed since it could not have been an inconvenience or a favor to either community; in 1898, Muslims were disallowed from stacking construction material in the enclosure since it hindered pedestrians; in 1904, a trough feeder for cows and a wall — constructed by Hindus— were demolished; in 1906, permission to rebuild the wall and install a new idol was rejected; in 1909, the municipality was allowed to pave a part of the enclosure.[67]

- ^ In 1921, a plinth was allowed to be constructed for the Peepal tree; in 1923, Muslims were prohibited from storing poultry in the enclosure; in 1924, Muslims were ordered to remove a temporary barricade; in 1925, Hindus constructed a shed over the ablution tank of their own cost to prevent bird-droppings from the peepal tree contaminating the ablution tank, as a compromise, after having refused to cut any branch.[67][74]

- ^ Nonetheless, the Court held the mosque and the plinth to be undisputed waqf property.

- ^ The High Court held that not only did the formation of enclosure post-date the mosque but also the enclosure was never in continuous possession of the Muslims (alone) for at-least the last hundred years. Thus, the plaintiff failed to establish any legal right.Further, recorded history of overflows into the enclosure went back to a few years, at most, and only on the occasion of a festive day. Thus, it was insufficient to give rise to customary rights.

- ^ Suit 610 of 1991.[79]

- ^ The Ayodhya dispute was stated as an exception to the PoW Act.

- ^ Here, it was claimed that the swayambhu lingam had existed in the compound for over a millennia —since the reign of one Vikramaditya— notwithstanding the superficial demolition of the temple by Aurangzeb and currently, Hindus were deprived of their religious right to offer water to the lingam.[80]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب ت ث Asher 1992, p. 278-279.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 84, 162.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 163.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 162, 247.

- ^ أ ب Desai 2017, p. 6.

- ^ أ ب ت Shin 2015, p. 36.

- ^ Asher 2020, p. 16.

- ^ أ ب ت ث O'Hanlon 2011, p. 264-265.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 60, 62.

- ^ Dumper 2020, p. 129.

- ^ أ ب ت Desai 2017, Introduction.

- ^ أ ب ت Searle-Chatterjee 1993.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 18.

- ^ أ ب ت Shin 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت Udayakumar, S. P. (2005). "Ramarajya: Envisioning the Future and Entrenching the Past". Presenting the Past: Anxious History and Ancient Future in Hindutva India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-275-97209-7.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 12.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Dumper 2020.

- ^ Dumper 2020, p. 125.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 218.

- ^ أ ب Bakker 1996, p. 42–43.

- ^ أ ب Desai 2017, Palimpsests.

- ^ Desai 2017, Authenticity and Pilgrimage.

- ^ Desai 2017, Palimpsests; Authenticity and Pilgrimage.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 6, 10.

- ^ أ ب Lazzaretti 2021a, p. 138.

- ^ أ ب Shin 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Truschke 2017.

- ^ Brown 2007.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Desai 2017, p. 69.

- ^ Asher 2020, p. 17.

- ^ أ ب Dumper 2020, p. 132.

- ^ Salaria 2022.

- ^ Lazzaretti 2021a, p. 140.

- ^ Eaton 2000, p. 306–307.

- ^ Truschke 2017, p. 85-86.

- ^ O'Hanlon 2011, p. 267.

- ^ Wink 2020, p. 194–195; 274 (note 98).

- ^ Copland et al. 2013, p. 119.

- ^ Searle-Chatterjee 1993, p. 152.

- ^ Askari 2012.

- ^ أ ب Askari 1978, p. 10-12.

- ^ Searle-Chatterjee 1993, p. 154.

- ^ Menon 2002, p. 344.

- ^ Dutta 2022.

- ^ Lazzaretti 2021c, p. 595–596.

- ^ Searle-Chatterjee 1993, p. 155-156.

- ^ Searle-Chatterjee 1993, p. 155.

- ^ أ ب Desai 2003.

- ^ أ ب ت Desai 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Desai 2017, pp. 58, 67.

- ^ Sherring 1868, pp. 54-55.

- ^ Desai 2017, pp. 66, 68.

- ^ Asher 2020, p. 22.

- ^ أ ب ت Desai 2017, Expansion.

- ^ أ ب Desai 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Shin 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 81, 233.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 83-84.

- ^ أ ب ت Desai 2017, p. 164.

- ^ Lazzaretti 2021b, p. 91.

- ^ Pandey 1989, p. 145.

- ^ أ ب ت Eck 1982.

- ^ Gaenszle & Gengnagel 2006.

- ^ Heber 1829, p. 257–258.

- ^ Lazzaretti 2021a, p. 142-143.

- ^ أ ب ت Sherring 1868, p. 54.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Allahabad High Court 1941.

- ^ Sherring 1868, p. 52.

- ^ Sherring 1868, p. 53.

- ^ Desai 2017, p. 165.

- ^ Greaves 1909, p. 80.

- ^ Greaves 1909, p. 82.

- ^ Greaves 1909, p. 80-82.

- ^ Lazzaretti 2021b, p. 90,97.

- ^ Times of India 1935.

- ^ Dumper 2020, p. 108.

- ^ Majumder 2004.

- ^ Chapple, Christopher Key; Tucker, Mary Evelyn (2000). Hinduism and Ecology: The Intersection of Earth, Sky, and Water. Harvard University Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-945454-26-7.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ahmed 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Taskin 2021.

- ^ Katju 2003, p. 113-114.

- ^ Engineer 1997, p. 324.

- ^ Yamunan 2021b.

- ^ Sarin 2017.

- ^ أ ب The Wire April 2021.

- ^ Kumar 2019.

- ^ Yamunan 2021a.

- ^ أ ب Upadhyay 2021.

ببليوگرافيا

- Desai, Madhuri (2017). Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295741604, ISBN 9780295741611.

- Searle-Chatterjee, Mary (1993). "Religious division and the mythology of the past". In Hertel, Bradley R.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (eds.). Living Banaras: Hindu Religion in Cultural Context. SUNY Series in Hindu Studies. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 145–158.

- Sherring, Matthew Atmore (1868). The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Trübner & co. pp. 51–56.

- Asher, Catherine B. (May 2020). "Making Sense of Temples and Tirthas: Rajput Construction Under Mughal Rule". The Medieval History Journal. 23 (1): 9–49. doi:10.1177/0971945820905289. ISSN 0971-9458.

- O'Hanlon, Rosalind (March 2011). "Speaking from Siva's temple: Banaras scholar households and the Brahman 'ecumene' of Mughal India". South Asian History and Culture. 2 (2): 264–265. doi:10.1080/19472498.2011.553496. ISSN 1947-2498. S2CID 145729224.

- Lazzaretti, Vera (2021b). "Demolitions, dream projects and the negotiation of Hinduness in Banaras". In Keul, István (ed.). Spaces of Religion in Urban South Asia (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. pp. 90–91. doi:10.4324/9781003106067-7. ISBN 978-1-000-33141-7.

- "Muslim Trouble in Benares: Police Force Stoned: Attempt to Pray Outside Mosque". Times of India. 20 December 1935.

- Lazzaretti, Vera (2021a). "Water And Conflicts Around Religious Heritage: Oscillations Between Centre And Periphery?". In Cortesi, Luisa; Joy, K. J. (eds.). Split Waters: The Idea of Water Conflicts (in الإنجليزية). India: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003030171-9. ISBN 9780367466428.

- Dutta, Prabhash K. (15 May 2022). "Gyanvapi: A 31-year dispute of 353-year-old shrine explained". The Times of India.

- Greaves, Edwin (1909). Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares. Allahabad: Indian Press. pp. 80–82.

- Katju, Manjari (2003). Vishva Hindu Parishad and Indian Politics. Orient Blackswan. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-81-250-2476-7.

- L. Eck, Diana (1982). Banaras: City of Light. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-83295-5.

- Askari, S. H. (1978). "Malfuzat: An Untapped Source of Social History — Ganj-i-Arshadi of the Jaunpur School — A Case Study". Khuda Bakhsh Library Journal. Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library. 7: 1–22.

- Salaria, Shikha (2022-05-19). "Aibak, Akbar, Aurangzeb—the Gyanvapi divide & why a controversial mosque has a Sanskrit name". ThePrint.

- Lazzaretti, Vera (2021c). "Religious Offence Policed: Paradoxical Outcomes of Containment at the Centre of Banaras, and the 'Know-How' of Local Muslims". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (in الإنجليزية). 44 (3): 584–599. doi:10.1080/00856401.2021.1923760. ISSN 0085-6401.

- Madhuri Desai (2003). "Mosques, Temples, and Orientalists: Hegemonic Imaginations in Banaras". Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review. 15 (1): 23–37. JSTOR 41758028.

- قالب:Cite court

- Dumper, Michael (2020). "Hindu–Muslim Rivalries in Banaras: History and Myth as the Present". Power, Piety, and People: The Politics of Holy Cities in the Twenty-First Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54566-2.

- Shin, Heeryoon (2015). Building a "Modern" Temple Town: Architecture and Patronage in Banaras, 1750-1900 (PhD). Yale University.

- Askari, S. H. (2012) [2000]. "GANJ-E ARŠADĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Brill. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_1891.

- Wink, André (2020). The making of the Indo-Islamic world : c. 700-1800 CE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-41774-7.

- Taskin, Bismi (2021-04-10). "Decoding the Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvapi dispute, and why Varanasi court has ordered ASI survey". ThePrint (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية).

- Kumar, Sushil (27 April 2019). "How Modi's Kashi Vishwanath Corridor is laying the ground for another Babri incident". The Caravan.

- "Court Revives Dormant Dispute, asks ASI to Survey Gyanvapi Mosque Next to Kashi Vishwanath Temple". The Wire. 8 April 2021.

- Yamunan, Sruthisagar (10 April 2021). "Why UP court order asking ASI to survey Kashi-Gyanvapi mosque complex is legally unsound". Scroll.in (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية).

- Yamunan, Sruthisagar (15 April 2021). "Analysis: Could ASI survey of Gyanvapi mosque lead to it being exempted from Places of Worship Act?". Scroll.in.

- Upadhyay, Sparsh (2021-09-09). "Gyanvapi Mosque Dispute: Allahabad High Court Stays Varanasi Court's ASI Survey Order & Other Proceedings". Live Law.

- Eaton, Richard M. (2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 306–307. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283. ISSN 0955-2340. JSTOR 26198197.

- Copland, Ian; Ian Mabbett; Asim Roy; Kate Brittlebank; Adam Bowles (2013). A History of State and Religion in India. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-45950-4.

- Menon, Kalyani Devaki (2002). "Living and Dying for Mother India: Hindu Nationalist Female Renouncers and Sacred Duty". In Mines, Diane P.; Lamb, Sarah (eds.). Everyday Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253340801. JSTOR j.ctt16gz5rp.

- Truschke, Audrey (2017). Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India's Most Controversial King. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-0259-5.

- Brown, Katherine Butler (2007). "Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Historiography of His Reign". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 41 (1): 77–120. doi:10.1017/S0026749X05002313. JSTOR 4132345.

- Asher, Catherine B. (September 1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.

- Bakker, Hans (1996). "Construction and Reconstruction of Sacred Space in Vārāṇasī". Numen. 43 (1). doi:10.1163/1568527962598368. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3270235.

- Eck, Diana L. (1982). Banaras: City of Light. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-83295-5.

- Gaenszle, Martin; Gengnagel, Jörg (2006). Visualizing Space in Banaras: Images, Maps, and the Practice of Representation. Isd. ISBN 978-3-447-05187-3.

- Pandey, Gyanendra (1989). "The Colonial Construction of 'Communalism': British Writings on Banaras in the Nineteenth Century". Subaltern Studies. Vol. VI. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Majumder, Sanjoy (2004-03-25). "Cracking India's Muslim vote". BBC News. Uttar Pradesh.

- Engineer, Asghar Ali (1997). "Communalism and Communal Violence, 1996". Economic and Political Weekly. 32 (7): 324. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4405088.

- Heber, Reginald (1829). Narrative of a journey through the upper provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-1825. Philadelphia, Carey, Lea & Carey.

- Sarin, Jitendra (8 May 2017). "Allahabad HC to hear Vishwanath temple, Gyanvapi mosque dispute on May 10". Hindustan Times.

- Ahmed, Areeb Uddin (11 April 2021). "All you need to know about the Gyanvapi Mosque - Kashi Vishwanath Temple land dispute". Bar & Bench (in الإنجليزية).

[[تصنيف:الدين في ڤرناسي]